Saturday, November 30, 2013

How Could This Happen to Annie Leibovitz?

[ed. I missed this fascinating article when it first came out in 2009. According to the most recent entry listed for Annie in Wikipedia her debt has since been restructured, although it's still not clear whether she has retained rights to her incredible catalog of work.]

Annie Leibovitz clearly hated what a lifetime-achievement award implied about her—that the best days of her 40-year career were behind her. “Photography is not something you retire from,” the 59-year-old Leibovitz said from the stage, accepting the honor from the International Center of Photography last May at Pier 60. She was turned out in a simple black dress and glasses, her long straight hair a little unruly, as usual. Photographers, she said, “live to a very old age” and “work until the end.” She noted that Lartigue lived to be 92, Steichen 93, and Cartier-Bresson 94. “Irving Penn is going to be 92 next month, and he’s still working.” Then her tone turned rueful. “Seriously, though, this really is a big deal,” she said, hoisting her Infinity Award statuette, her voice quavering to the point where it seemed she might cry. “It means so much to me, you know, especially right now. It’s, it’s a very sweet award to get right now. I’m having some tough times right now, so … ”

Annie Leibovitz clearly hated what a lifetime-achievement award implied about her—that the best days of her 40-year career were behind her. “Photography is not something you retire from,” the 59-year-old Leibovitz said from the stage, accepting the honor from the International Center of Photography last May at Pier 60. She was turned out in a simple black dress and glasses, her long straight hair a little unruly, as usual. Photographers, she said, “live to a very old age” and “work until the end.” She noted that Lartigue lived to be 92, Steichen 93, and Cartier-Bresson 94. “Irving Penn is going to be 92 next month, and he’s still working.” Then her tone turned rueful. “Seriously, though, this really is a big deal,” she said, hoisting her Infinity Award statuette, her voice quavering to the point where it seemed she might cry. “It means so much to me, you know, especially right now. It’s, it’s a very sweet award to get right now. I’m having some tough times right now, so … ”The 700 friends and colleagues who had come to share the evening with her knew about the “tough times.” Two vendors had sued her for more than $700,000 in unpaid bills, and in February, the New York Times ran a front-page story reporting that in order to secure a loan, Leibovitz had essentially pawned the copyrights to her entire catalogue of photographs. Even those who had known she was in trouble were shocked by the extent of it. Leibovitz was responsible for some of the world’s most iconic magazine covers—a naked John Lennon with Yoko Ono for Rolling Stone, Demi Moore, naked and pregnant, for Vanity Fair. She had moved from celebrity portraiture to fashion photography to edgier, more artistic pictures; some considered her the heir to Richard Avedon or Helmut Newton.

Despite being a compulsive perfectionist whose shoots cost a fortune to produce, Leibovitz was very much in demand. People spoke of a fabled “contract for life” from Condé Nast, thought to bring her as much as $5 million annually. (The estimate didn’t seem far-fetched; a decade ago, the Times reported that Condé Nast chairman Si Newhouse had instructed Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter not to “nickel and dime” Leibovitz over the issue of an extra quarter-million dollars in her contract.) She was said to earn a day rate of $250,000 just to set foot in a studio for an advertising job for clients like Louis Vuitton. Over the years, Leibovitz had bought and sold a small fortune in real estate—a penthouse in Chelsea with a photo studio nearby, a sprawling townhouse in Greenwich Village, a compound in Rhinebeck once owned by the Astor family, and a Paris pied-à-terre overlooking the Seine. Virtually anyone (the Queen of England, for instance) would agree to be photographed by her, and she had a longtime relationship with the celebrated writer and intellectual Susan Sontag.

Lately, however, Leibovitz’s life had taken a decidedly dark turn. Her reference to “tough times” was significantly understated. In the past five years, Sontag and both of Leibovitz’s parents have died. Her debts now total a staggering $24 million, consolidated with one lender with whom she is engaged in a lawsuit and due in September. If she can’t meet that deadline, she may lose her homes and the rights to her life’s body of work.

Friends say Leibovitz has begun to think of herself less as a celebrity artist leading a charmed life and more as a single mother of three fighting to keep a roof over her head and food on her family’s table. It isn’t surprising, then, that she bristled at a lifetime-achievement award. The fear of no longer working is terrifying to her. She has to work. What remains mystifying is the simple question on everyone’s mind that night: How on earth could something like this have happened to Annie Leibovitz?

by Andrew Goldman, New York Magazine | Read more:

Image: John Keatley/ReduxThe Death and Life of Great Internet Cities

Petsburg appears to have enjoyed a bustling commercial district during its heyday. There were shops where one could do everything from having their age in dog years calculated to adopting one of the community’s abandoned pets. The neighborhood library recorded the histories of ancient creatures, like, for instance, the Egyptian Mau (“To gaze upon this beautiful and engaging [cat] is an opportunity to view a living relic,” one historian wrote.) Meanwhile, its scientists painstakingly chronicled the stages of gerbil pregnancies (“12/23/98: Moonflash and Chequers could double as gourds! they are both expecting any time now,” a researcher observed.) Visitors traveled the neighborhood on Webrings, leaving their mark in each home’s guestbook. The local newspaper was the Petsburg Post, though no copy has survived the community’s complete collapse.

Petsburg was just one of the 40 neighborhoods that made up the metropolis of Geocities, which, in its 15 years of existence, housed some 38 million online residents. It was arguably the world’s first and last Internet city. Were it a physical place, it would have been by far the largest urban area in the world.

It was shuttered in 2009, but several archive groups and individuals have sought to preserve it on mirror sites like Reocites and Oocities, and in massive torrent files. A relic from the early days of the Internet, frozen and downloadable, the files tell the story of the city’s rise and downfall, the story of how we found our place online.

Geocities began in 1994, advertising an enticing 15 megabytes of free space to any homesteader looking to make their place on the Web. The World Wide Web was only a few years old when this digital Northwest Ordinance was issued, and so its users, often referred to as netizens, were necessarily having their first interactions with the Internet, learning to make a place for themselves in the newly discovered online world. Millions of netizens with little to no experience or understanding of how a webpage “should” look utilized the site’s built-in development tools to create clapboard homes spattered with stray GIFs, looping MIDI files, and busy backgrounds. It was the Internet's Wild West.

It is easy to dismiss these pages as a sort of outsider art. But outside of what? There was no such thing as a personal page before Geocities. And, in almost every meaningful sense of that word, there is no equivalent today. Consider a page from the Heartland neighborhood, where one resident wrote, “Hi! My name is Sherry, my husband is Richard. We have three children, Colleen, Alicia and James and we are out here in the desert of southern California.” Further down on the page is a link to “Richard’s Original Bedtime Stories”: “Once upon a time there was a mad scientist, and this mad scientist had a laboratory. In his lab the scientist had a shelf and on the shelf was a jar. In that jar was a pickle and in the pickle was DNA. This DNA was different, it was dinosaur DNA...”

Where today do families publish their homemade bedtime stories about giant pickles? Sites like these have simply disappeared.

Geocities was bought by Yahooin 1999, during the height of its popularity. Then along came Myspace in 2003, Facebook in 2004, and Twitter in 2006. And by 2009, Petsburg, Heartland, and the rest of Geocities had been shuttered. The world had chosen the pre-fab aesthetics of social networks over the 15-megabyte tracts of open land offered by Geocities. Jacques Mattheij, the founder of the Geocities archive site Reocities, explained this choice to me: “The Geocities environment offered more freedom for expression. Don't like blue? Then Facebook probably isn't for you.”

Whatever we may ultimately make of our move towards sites like Facebook, it’s almost certainly the case that, for the average netizen, it was a movement away from online literacy. Instead of slogging through the HTML editor of Geocities—and coming to terms with how these tools can be used to express oneself in a digital space—we chose the sleek, standardized layouts of Facebook and Myspace.

“There's no way to look at the Facebook page and not know that you're on Facebook,” Jason Scott, who worked on a Geocities preservation project with Archive Team, told me. “In fact, it's hard to be on Facebook and even feel like people are contributing much beyond links and a paragraph of text.”

Online and before, we’ve always made these choices. The American west is littered with forgotten towns, single-economy communities that cropped up to mine gold, build railroads, or raise livestock as the country made its stubborn progress to the Pacific. Those that survived eventually lost their pioneer character.

by Joe Kloc, Daily Dot | Read more:

Image: Jason Reed

Close the Store, It’s the Year’s Big Game in Alabama

[ed. See also: The Most Poisonous Rivaly in Sports. Postscript: It was Mayhem. Man,what a game.]

The Saturday evening Mass at St. Michael the Archangel Catholic Church here will be a cappella because the organist has football tickets. Weddings and funerals will be rarities. Car dealerships are expected to go dark. The J & M Bookstore will close at kickoff — and reopen after the game only if the home team wins.

The Saturday evening Mass at St. Michael the Archangel Catholic Church here will be a cappella because the organist has football tickets. Weddings and funerals will be rarities. Car dealerships are expected to go dark. The J & M Bookstore will close at kickoff — and reopen after the game only if the home team wins.The normal course of civil society in this state is transformed every year when Auburn University and the University of Alabama meet for what some believe is just a football game and what others see as a test of moral virtue. But the 78th matchup in what is now known as the Iron Bowl will be the first time the winner will grab the usual statewide bragging rights while simultaneously keeping its national title hopes alive and earning a spot in the Southeastern Conference championship game.

As a result, almost everything outside Jordan-Hare Stadium figures to sputter to a halt for a four-hour stretch on Saturday as top-ranked Alabama seeks an undefeated regular season, No. 4 Auburn enjoys its abrupt resurgence as a football power, and the state proves there are few limits to its infatuation with all things pigskin-related.

And the observances won’t end on Saturday. The Sunday sermon at the Auburn Church of Christ will be about humility because, as its sign along South College Street put it, “We’ll either have it or need it.”

“It’s gigantic. It’s for all the marbles,” said Eric Stamp, who owns a print shop in Auburn. “People change their Thanksgiving weekend plans to accommodate the Iron Bowl.” (For decades, the game was played in Birmingham, known for iron and steel production.)

The Alabama faithful concur. “Everyone knows going in that if your team loses, it will hurt you for decades. Just the mention of it in 25 years will cause certain people to retch in despair,” said Warren St. John, a former reporter for The New York Times whose book “Rammer Jammer Yellow Hammer,” documenting the zeal of Crimson Tide supporters, was once the textbook for a University of Alabama course about the culture surrounding Southern football.

by Alan Blinder, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Dustin Chambers Friday, November 29, 2013

The Flop

I was not informed directly that the website would not be working the way it was supposed to. Had I been informed, I wouldn’t be going out saying, boy, this is going to be great. I’m accused of a lot of things, but I don’t think I’m stupid enough to go around saying, this is going to be like shopping on Amazon or Travelocity a week before the website opens if I thought that it wasn’t going to work.And so we are left to wonder how it was that the president not only had not been informed (note the passive construction), but how it was that he did not make it a point to be informed, not merely because he is the president and that’s his job, not merely because he has made health care the legislative priority of his administration, not merely because affordable health care is the hook on which he hopes to hang his presidential legacy, and not merely because the Republicans have been trying to thwart him at every turn, but because of all of these. Knowing how sensitive Americans are to the shortcomings of big government should have made Obama especially vigilant to the disasters ahead if his administration botched HealthCare.gov. On November 19, his spokesman, Jay Carney, admitted that the president had in fact been briefed in April about the danger that the website would fail when it was launched in October. His carelessness will be a good place for historians to begin to unwrap the enigma of a president who appears to run the country on a need-to-know basis, ceding what needs to be known to other people. (...)

“There aren’t a lot of websites out there that have to help people compare their possible insurance options, verify income to find out what kind of tax credits they might get, communicate with those insurance companies so they can purchase, make sure that all of it’s verified,” the president said in that November news conference. He then suggested that such a task was too difficult for the same government that, for instance, has designed the greatest online data-mining surveillance apparatus in the world: “The federal government does a lot of things really well. One of the things it does not do well is information technology procurement.”

Even so, there are many successful computer systems and websites both within the government (the Defense Logistics Agency comes to mind) and outside of it (Amazon, Google, Kayak) whose complex gearing is housed behind a simple interface. Businesses know that they’ve got five seconds of a user’s attention before that potential customer moves on—it’s what drives them to make the navigation of their websites as easy as possible. Since its launch, HealthCare.gov has often exceeded this by over 3,600 seconds due to software glitches, log-in overload, and a user experience that is remarkably cumbersome: it requires people first to set up an account that includes divulging personal information and having it verified by the Department of Homeland Security, the Internal Revenue Service, and the Social Security Administration before they can see how much it will cost to buy insurance. Imagine having to prove your income and residence and employment status before being able to look for—let alone buy—a pair of pants on Amazon.

by Sue Halpern, NY Review of Books | Read more:

Image: uncredited

Parking Apps

The fight for a mall parking spot, long a necessary evil of Black Friday, is growing easier thanks to the proliferation of new technologies, from apps and sensors to color-coded lights and electronic boards.

It’s one way that malls and shopping districts are trying to lure customers away from their computers, into the realm of their brick-and-mortar stores.

It’s one way that malls and shopping districts are trying to lure customers away from their computers, into the realm of their brick-and-mortar stores.

“What happens when there’s no spots? People drive around and become frustrated,” said Kathy Grannis, a spokeswoman for the National Retail Federation. “Who wants to start their shopping experience frustrated?”

ParkMe, which tracks more than 28,000 locations worldwide, has emerged as a mainstay app for mall customers navigating the nation’s parking lots. With the app, they can find the closest and least expensive lots, as well as alternative garage entrances. The app’s user base surged 97 percent in the past year, and it is adding hundreds of garages to its database.

“If there’s a way to get in off the beaten path, you can reduce stress,” said Sam Friedman, ParkMe’s co-founder and chief executive.

The app’s technology is simple enough: a magnetic loop at the garage clocks the number of times the gate lifts to admit or release a car, Mr. Friedman said. ParkMe also lets a customer reserve a spot in certain locations, like the Shore Hotel down the road from Santa Monica Place. Ms. Scott said she used that service during busy summer months.

Other parking apps are gaining traction as well. Parkopedia, which is linked to 26,000 lots in North America, also allows users to search parking sites, availability and prices using their smartphones. QuickPay plans to start in hundreds of malls in the United States next year to help shoppers pay for garage and metered spots and valet services from their smartphone. (...)

Jessi Molohon, a 23-year-old student at the University of Texas at Austin, is one such customer. She said she uses the ParkWhiz app when traveling to stores in downtown Houston or at the Houston Galleria to help find garages and compare prices.

“Parking can be anywhere from $6 to $12 on the same street, so I want to make sure I’m not overspending on parking when I’m going to overspend on shopping,” Ms. Molohon said.

An app called A Parking Spot lets Ms. Molohon pin her favorite parking spaces on a Google map so that she can navigate there next time.

“I have it down to a routine,” she said. “There are some spots I know of that are just easy to get in and out of that will help me save time and avoid the holiday traffic just a little.”

It’s one way that malls and shopping districts are trying to lure customers away from their computers, into the realm of their brick-and-mortar stores.

It’s one way that malls and shopping districts are trying to lure customers away from their computers, into the realm of their brick-and-mortar stores.“What happens when there’s no spots? People drive around and become frustrated,” said Kathy Grannis, a spokeswoman for the National Retail Federation. “Who wants to start their shopping experience frustrated?”

ParkMe, which tracks more than 28,000 locations worldwide, has emerged as a mainstay app for mall customers navigating the nation’s parking lots. With the app, they can find the closest and least expensive lots, as well as alternative garage entrances. The app’s user base surged 97 percent in the past year, and it is adding hundreds of garages to its database.

“If there’s a way to get in off the beaten path, you can reduce stress,” said Sam Friedman, ParkMe’s co-founder and chief executive.

The app’s technology is simple enough: a magnetic loop at the garage clocks the number of times the gate lifts to admit or release a car, Mr. Friedman said. ParkMe also lets a customer reserve a spot in certain locations, like the Shore Hotel down the road from Santa Monica Place. Ms. Scott said she used that service during busy summer months.

Other parking apps are gaining traction as well. Parkopedia, which is linked to 26,000 lots in North America, also allows users to search parking sites, availability and prices using their smartphones. QuickPay plans to start in hundreds of malls in the United States next year to help shoppers pay for garage and metered spots and valet services from their smartphone. (...)

Jessi Molohon, a 23-year-old student at the University of Texas at Austin, is one such customer. She said she uses the ParkWhiz app when traveling to stores in downtown Houston or at the Houston Galleria to help find garages and compare prices.

“Parking can be anywhere from $6 to $12 on the same street, so I want to make sure I’m not overspending on parking when I’m going to overspend on shopping,” Ms. Molohon said.

An app called A Parking Spot lets Ms. Molohon pin her favorite parking spaces on a Google map so that she can navigate there next time.

“I have it down to a routine,” she said. “There are some spots I know of that are just easy to get in and out of that will help me save time and avoid the holiday traffic just a little.”

by Jaclyn Trop, NY Times | Read more:

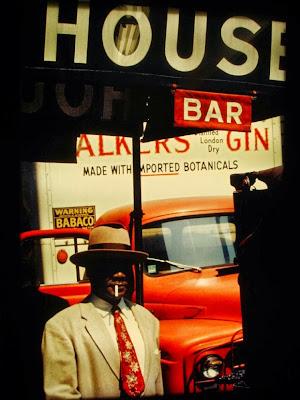

Image: J. Emilio FloresSaul Leiter (December 3, 1923 – November 26, 2013)

New York at midcentury was a monochrome town, or so its best-known documentarians would have us believe.

But where eminent photographers like Weegee, Diane Arbus and Richard Avedon captured the city most often in clangorous, sharp-edged black and white, Saul Leiter saw it as a quiet polychrome symphony — the glow of neon, the halos of stoplights, the golden blur of taxis — a visual music that few of his contemporaries seemed inclined to hear.

One of the first professionals to photograph New York City regularly in color, Mr. Leiter, who died on Tuesday at 89, was among the foremost art photographers of his time, despite the fact that his work was practically unknown to the general public.

One of the first professionals to photograph New York City regularly in color, Mr. Leiter, who died on Tuesday at 89, was among the foremost art photographers of his time, despite the fact that his work was practically unknown to the general public.Of the tens of thousands of images he shot — many now esteemed as among the finest examples of street photography in the world — most remain unprinted.

Trained first as a rabbi and then as a painter, Mr. Leiter the photographer spent the last 60 years being cyclically forgotten and rediscovered. In the end he remained very nearly the antithesis of a household name, a state of affairs that, with his lifelong craving for privacy and genial constitutional dyspepsia, he found hugely satisfying.

“In order to build a career and to be successful, one has to be determined,” Mr. Leiter said in an interview for a monograph published in Germany in 2008. “One has to be ambitious. I much prefer to drink coffee, listen to music and to paint when I feel like it.” (...)

Mr. Leiter was considered a member of the New York School of photographers — the circle that included Weegee and Arbus and Avedon — and yet he was not quite of it. He was largely self-taught, and his work resembles no one else’s: tender, contemplative, quasi-abstract and intensely concerned with color and geometry, it seems as much as anything to be about the essential condition of perceiving the world.

“Seeing is a neglected enterprise,” Mr. Leiter often said. (...)

Unplanned and unstaged, Mr. Leiter’s photographs are slices fleetingly glimpsed by a walker in the city. People are often in soft focus, shown only in part or absent altogether, though their presence is keenly implied. Sensitive to the city’s found geometry, he shot by design around the edges of things: vistas are often seen through rain, snow or misted windows.

“A window covered with raindrops interests me more than a photograph of a famous person,” Mr. Leiter says in “In No Great Hurry.”

by Margalit Fox, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Saul Leiter via:

Thursday, November 28, 2013

Kill Your Own Business

Jeff Bezos thinks of himself as a great man, and why shouldn’t he? ‘Our vision is to have every book ever printed, in any language, available in under 60 seconds.’ He wrote that ten years ago; now it’s almost true. When he graduated from high school, first in his class, he gave a speech to his classmates on how the fragility of the Earth required them to explore outer space and work towards rehousing humanity in orbiting space stations. He has used some of his fortune to turn 290,000 acres in West Texas into a giant laboratory for new spacecraft, which he claims will be so efficient and inexpensive to service that everyone will eventually be able to leave the planet. In his annual letter to the shareholders of Amazon, he acknowledges that some of his decisions may seem inexplicable, but ‘it’s all about the long-term.’ To that end, he has donated $42 million to the construction of the Clock of the Long Now, which is supposed to tick for 10,000 years. His temporarily is not our temporarily.

Jeff Bezos thinks of himself as a great man, and why shouldn’t he? ‘Our vision is to have every book ever printed, in any language, available in under 60 seconds.’ He wrote that ten years ago; now it’s almost true. When he graduated from high school, first in his class, he gave a speech to his classmates on how the fragility of the Earth required them to explore outer space and work towards rehousing humanity in orbiting space stations. He has used some of his fortune to turn 290,000 acres in West Texas into a giant laboratory for new spacecraft, which he claims will be so efficient and inexpensive to service that everyone will eventually be able to leave the planet. In his annual letter to the shareholders of Amazon, he acknowledges that some of his decisions may seem inexplicable, but ‘it’s all about the long-term.’ To that end, he has donated $42 million to the construction of the Clock of the Long Now, which is supposed to tick for 10,000 years. His temporarily is not our temporarily.Bezos was born in 1964 in New Mexico. His mother was 16; his father, not much older, was a unicyclist in a circus. Bezos never knew him, and he was adopted by his mother’s second husband, a Cuban petroleum engineer who fled Castro as a teenager and told Brad Stone that he takes credit for passing on a ‘libertarian aversion to government intrusion into the private lives and enterprises of citizens’. To taxes, for example. Jeff did well at school, particularly in maths and science; he went to Princeton; and by the age of 28 he was one of the vice presidents of a New York investment firm. In 1994, when the World Wide Web was a year old, he made a list of things that he might be able to sell in great quantities over the internet. In a supposed triumph for mail order and catalogue companies, the US Supreme Court had decided that businesses weren’t required to collect sales tax on behalf of any state in which they lacked a ‘physical presence’. Anything sold online was going to be cheaper than almost anything sold in a shop. Someone was going to make a fortune. Bezos created a ‘regret minimisation framework’:

I knew when I was eighty that I would never, for example, think about why I walked away from my 1994 Wall Street bonus … At the same time, I knew that I might sincerely regret not having participated in this thing called the internet that I thought was going to be a revolutionising event. When I thought about it that way … it was incredibly easy to make the decision.Bezos’s list included clothes, computer software and office supplies. What he liked about books was that they were ‘pure commodities’: copies of the latest Stephen King sold online would be no better or worse than those sold in shops. But no actual shop was big enough to offer all the three million-plus books in print. Two distributors, Ingram and Baker & Taylor, handled distribution for most American publishers: Bezos wouldn’t have to make separate deals with each publishing house. Books also came assigned with International Standard Book Numbers and were catalogued on CD-ROM: that would save time, and Bezos was in a hurry.

The company’s motto was ‘Get Big Fast’. The Amazon isn’t just the largest river in the world: it’s larger than the next seven largest rivers combined. Bezos preferred the name Relentless.com, but friends persuaded him that it sounded sinister. (Type Relentless into an address bar and you still get directed to Amazon.) He also considered Bookmall.com (but he knew that soon enough he wouldn’t only be selling books) and Cadabra.com (sounded too much like ‘cadaver’). Naturally he couldn’t set up the business in New York – too many potential customers lived there, and he didn’t want to charge them all sales tax – but somewhere isolated would make it difficult to hire engineers. The compromise was Seattle: at least Microsoft was nearby. Washington is also one of the few American states that doesn’t charge any personal income tax. (In 2010, Bezos donated $100,000 to a campaign that successfully defeated Initiative 1098, supported by Bill Gates, which would have started taxing those who earn more than $200,000 a year.) Bezos took a four-day bookselling course through the American Booksellers Association. He used his savings and took out loans to hire a small staff, and his parents put up money from their retirement fund. They didn’t know anything about the internet, but they trusted him.

At first only web geeks shopped from Amazon, and for a year its bestselling book was How to Set Up and Maintain a World Wide Web Site: The Guide for Information Providers. To make the site livelier Bezos hired an editorial team to review books, but sacked them when he realised that customers preferred doing it themselves. (My first book review was a freebie for Amazon: five stars for Jane Eyre.) Distributors made Amazon order ten books at a time, but Bezos got round the system:

You didn’t have to receive ten books, you only had to order ten books. So we found an obscure book about lichens that they had in their system but was out of stock. We began ordering the one book we wanted and nine copies of the lichen book. They would ship out the book we needed and a note that said: ‘Sorry, but we’re out of the lichen book.’

Amazon advertised itself as the world’s largest bookstore, but didn’t actually hold any stock: a customer would order a book from Amazon, Amazon would order it from a distributor and pass it on. It was the kind of transaction that ordinary bookshops do all the time: the difference was that Amazon – run from Bezos’s garage, later from crummy offices in the cheapest part of town – could afford to take 30 or 40 per cent off bestsellers, 10 per cent off everything else. Any business meetings were held in a café inside a branch of Barnes and Noble.

According to Stone’s The Everything Store, which charts Amazon’s growth from bookseller to all-around mercantile hegemon, one of Bezos’s favourite books is Sam Walton’s autobiography, Made in America, about the creation of Wal-Mart. Bezos made his top employees read it, then realised that it was simplest just to replace or augment them with executives from Wal-Mart – so many of them that Wal-Mart sued, alleging that Amazon was stealing trade secrets. Walton’s creed, as Bezos understood it, was to have lower prices than your competitors, even if doing so cut into your profits or meant you had to treat your employees like garbage. With lower prices you’ll get more customers; with more customers you can push suppliers to lower their prices, which will let you lower your prices even further, thereby attracting more customers; repeat until your competitors are dust. Mega-bookstores – Borders and Barnes and Noble – were slow to take to the web, but Bezos prepared for them by patenting ‘1-Click’ checkout, which just meant that customers’ shipping and billing details were saved and stored: no need to type them out next time. The patent was written so broadly that when Barnes and Noble did start selling books online, Amazon was able to prevent their ‘Express Lane’ checkout, even though it required two clicks. Every American webstore was forced to be clunkier than Amazon unless, like Apple, it paid Amazon huge licensing fees. This lasted until 2006, when a New Zealand actor with a side interest in intellectual property law finally produced evidence that another e-commerce company had actually patented one-click shopping first, under a different name. But by then most of Amazon’s would-be competitors were defunct.

by Deborah Friedell, LRB | Read more:

Image: TNW

Ego Depleted

Consumerism is sustained by the ideology that freedom of choice is the only relevant freedom; it implies that society has mastered scarcity and that accumulating things is the primary universal human good, that which allows us to understand and relate to the motives of others. We are bound together by our collective materialism.

Choosing among things, in a consumer society, is what allows us to feel autonomous (no one tells us how we must spend our money) and express, or even discover, our unique individuality — which is proposed as the purpose of life. If we can experience ourselves as original, our lives will not have been spent in vain. We will have brought something new to human history; we will have been meaningful. (This is opposed to older notions of being “true” to one’s station or to God’s plan.)

Choosing among things, in a consumer society, is what allows us to feel autonomous (no one tells us how we must spend our money) and express, or even discover, our unique individuality — which is proposed as the purpose of life. If we can experience ourselves as original, our lives will not have been spent in vain. We will have brought something new to human history; we will have been meaningful. (This is opposed to older notions of being “true” to one’s station or to God’s plan.)

The quest for originality collides with the capitalist economic imperative of growth. The belief that more is better carries over to the personal ethical sphere, so that making more choices seems to mean a more attenuated, bigger, more successful self. The more choices we can make and broadcast to others, the more of a recognized identity we have. Originality can be regarded as a question of claiming more things to link to ourselves and combining them in unlikely configurations.

If we believe this, then it seems like good policy to maximize the opportunities to make consumer choices for as many people as possible. This will give more people a sense of autonomy, social recognition, and personal meaning. Considering the amount of time and space devoted to retail in the U.S., it seems as though we are implementing this ideology collectively. The public-policy goals become higher incomes, more stores, and reliable media through which to display personal consumption. This supposedly yields a population that is fulfilling its dreams of self-actualization.

But when you add the possibility of ego depletion — the loss of well-being due to overtaxing the executive decision-making function of the mind; it’s explained in this 2011 New York Times piece by John Tierney on “decision fatigue” — to this version of identity, it no longer coheres. Trying to grow the self through exercising market choice simultaneously generates a scarcity of “ego” resources, which are depleted by this sort of reflexive approach to performing the self as a rational decision-maker above all. “When you shop till you drop, your willpower drops, too,” Tierney writes. The choices become progressively less rational, less representational, less “original,” and more prone to being automatic or being manipulated by outside interests, thus ceasing to be emblematic of the “true self.” Instead of elaborating a more coherent self through a series of decisions, one establishes an increasingly incoherent and disunified self that is increasingly unpredictable and illegible to others. We lose the energy to think about who we are and act accordingly, and we begin acting efficiently instead, with increasingly less interest in coherence, justice, consistency, morality, and so on. We want to make the “convenient” choices rather than the ethical ones, the ones that we believe reflect the truth about us.

This represents a serious threat to economic models hinging on rational actors and “revealed preference,” as behavioral economics has attempted to demonstrate. It underwrites the business model of nickel-and-diming consumers into submission, as airlines have recently taken to doing. But it also muddles the self that has been fostered by consumerism. It suggests that consumerism is a control strategy based on exhaustion, not fulfillment.(...)

Advertising from this perspective is less useful information and more a series of temptations that constitute an assault to the integrity of the self, which depends on conserving the choices it makes to remain “authentic.” The threat of ego depletion also makes invitations to “share” the self and engage in social media into threats to that self as well, as long as it is understood to be a sum of communicative choices and not the ongoing process of confronting them. The endless opportunities social media afford for users to interact end up depleting the self (as it was once understood), resulting in the curious situation where the more one uses social media, the more desubjectified one becomes. The more you share, the less rational selfhood you possess.

Choosing among things, in a consumer society, is what allows us to feel autonomous (no one tells us how we must spend our money) and express, or even discover, our unique individuality — which is proposed as the purpose of life. If we can experience ourselves as original, our lives will not have been spent in vain. We will have brought something new to human history; we will have been meaningful. (This is opposed to older notions of being “true” to one’s station or to God’s plan.)

Choosing among things, in a consumer society, is what allows us to feel autonomous (no one tells us how we must spend our money) and express, or even discover, our unique individuality — which is proposed as the purpose of life. If we can experience ourselves as original, our lives will not have been spent in vain. We will have brought something new to human history; we will have been meaningful. (This is opposed to older notions of being “true” to one’s station or to God’s plan.)The quest for originality collides with the capitalist economic imperative of growth. The belief that more is better carries over to the personal ethical sphere, so that making more choices seems to mean a more attenuated, bigger, more successful self. The more choices we can make and broadcast to others, the more of a recognized identity we have. Originality can be regarded as a question of claiming more things to link to ourselves and combining them in unlikely configurations.

If we believe this, then it seems like good policy to maximize the opportunities to make consumer choices for as many people as possible. This will give more people a sense of autonomy, social recognition, and personal meaning. Considering the amount of time and space devoted to retail in the U.S., it seems as though we are implementing this ideology collectively. The public-policy goals become higher incomes, more stores, and reliable media through which to display personal consumption. This supposedly yields a population that is fulfilling its dreams of self-actualization.

But when you add the possibility of ego depletion — the loss of well-being due to overtaxing the executive decision-making function of the mind; it’s explained in this 2011 New York Times piece by John Tierney on “decision fatigue” — to this version of identity, it no longer coheres. Trying to grow the self through exercising market choice simultaneously generates a scarcity of “ego” resources, which are depleted by this sort of reflexive approach to performing the self as a rational decision-maker above all. “When you shop till you drop, your willpower drops, too,” Tierney writes. The choices become progressively less rational, less representational, less “original,” and more prone to being automatic or being manipulated by outside interests, thus ceasing to be emblematic of the “true self.” Instead of elaborating a more coherent self through a series of decisions, one establishes an increasingly incoherent and disunified self that is increasingly unpredictable and illegible to others. We lose the energy to think about who we are and act accordingly, and we begin acting efficiently instead, with increasingly less interest in coherence, justice, consistency, morality, and so on. We want to make the “convenient” choices rather than the ethical ones, the ones that we believe reflect the truth about us.

This represents a serious threat to economic models hinging on rational actors and “revealed preference,” as behavioral economics has attempted to demonstrate. It underwrites the business model of nickel-and-diming consumers into submission, as airlines have recently taken to doing. But it also muddles the self that has been fostered by consumerism. It suggests that consumerism is a control strategy based on exhaustion, not fulfillment.(...)

Advertising from this perspective is less useful information and more a series of temptations that constitute an assault to the integrity of the self, which depends on conserving the choices it makes to remain “authentic.” The threat of ego depletion also makes invitations to “share” the self and engage in social media into threats to that self as well, as long as it is understood to be a sum of communicative choices and not the ongoing process of confronting them. The endless opportunities social media afford for users to interact end up depleting the self (as it was once understood), resulting in the curious situation where the more one uses social media, the more desubjectified one becomes. The more you share, the less rational selfhood you possess.

by Rob Horning, Marginal Utility, TNI | Read more:

Image: Anne Arden MacDonaldSilicon Chasm

[ed. I know, another Silicon Valley article, and you're probably getting sick of them by now. But I find the process of societal transformation in a winner take all economy both fascinating and troubling, a new feudalism as Joel Kotkin terms it - especially the effect it's having on our great cities (not to mention our standard of living). New York, Seattle, San Francisco - all evolving into gentrified, exclusive enclaves for the newly rich. Silicon Valley is the new Wall Steet.]

Atherton, Calif. "If you live here, you’ve made it,” David Berkey said to me as I rode shotgun in his car two months ago through the Silicon Valley’s wealth belt. The massive house toward which he was pointing belongs to Sergey Brin, cofounder of Google. With a net worth of $24 billion, Brin is Silicon Valley’s third-richest denizen and the fourteenth-richest man in America, according to Forbes. Berkey was chauffeuring me down Atherton Avenue, a wide, straight, completely tree-lined boulevard nicely bifurcating the city of Atherton (population 7,200), located 29 miles south of San Francisco, boasting no commercial real estate, and with a zip code (94027) that was recently listed by Forbes as America’s most expensive.

Atherton, Calif. "If you live here, you’ve made it,” David Berkey said to me as I rode shotgun in his car two months ago through the Silicon Valley’s wealth belt. The massive house toward which he was pointing belongs to Sergey Brin, cofounder of Google. With a net worth of $24 billion, Brin is Silicon Valley’s third-richest denizen and the fourteenth-richest man in America, according to Forbes. Berkey was chauffeuring me down Atherton Avenue, a wide, straight, completely tree-lined boulevard nicely bifurcating the city of Atherton (population 7,200), located 29 miles south of San Francisco, boasting no commercial real estate, and with a zip code (94027) that was recently listed by Forbes as America’s most expensive.

You couldn’t really see Brin’s house from the car, though—just a swatch of rooftop, maybe a chimney—because the point of the trees lining Atherton Avenue and nearly every other street in Atherton is to hide the dwellings behind them. Where the screens of trees happen to thin, property owners have constructed high hedges, high wooden fences, and high brick walls, so that when you look down Atherton Avenue from the Santa Cruz Mountains to the west toward the commuter railroad station to the east, you see only the allée of trees—pine, palms, eucalyptus, sycamore, and juniper—shades of gray-green and brown-green shimmering placidly in the early autumn sun. “This is the Champs-Élysées of Atherton,” Berkey explained. The other thing we didn’t see from Berkey’s car is people, except for the occasional driver on the road.

Turning corners, we drove past other fancy and half-hidden real estate owned by other Silicon Valley grandees; Sheryl Sandberg, the COO of Facebook, and her husband David Goldberg, the CEO of SurveyMonkey, have a 7,200-square-foot house somewhere in the hedge maze. Before there was such a thing as Silicon Valley—that is to say, 40 years ago—Atherton was an affluent bedroom town for white-shoe law-firm partners and Old Economy executives who liked to ride the Southern Pacific Peninsula to their jobs in San Francisco, imitating their East Coast counterparts who rolled on the Hartford-New Haven line from the Southern Connecticut Gold Coast into Manhattan. That was before today’s hiding-the-house custom, and the executives’ front lawns surged out like green carpets to Atherton Avenue and its side streets. Now, Atherton is mostly teardowns and brand new mega-mansions—or at least as mega as their owners can get away with, given Atherton’s highly restrictive zoning laws that mandate enormous lot-to-footprint ratios. To increase their overall square footage, Atherton’s new breed of homeowners typically tunnel out vast underground extra space—wine cellars and home theaters—beneath their dwellings. The dominant style these days is a fanciful mix of Palladian Neoclassic, Loire Valley château, and Mediterranean villa, spreading out manor-house-style to cover as much ground as the zoning laws allow.

“This was a vacant lot five years ago,” said Berkey as we cruised by one of the spanking new stone-faced Atherton domiciles with its multiple dormers, chimneys, tile-roofed turrets, and columned porticos. “Now it’s worth $5 or $6 million. And this house here—it recently sold for $7 million, $4.4 million more than the asking price.” We passed the Menlo School, tuition $38,000 a year, where the parents pick up their kids in Range Rovers and fly them in private jets to exotic foreign locations for birthday parties. Down the road lay the Sacred Heart School, the Menlo School’s Catholic opposite number, where the tuition is only $34,000 a year. Their feeder is Atherton’s Las Lomitas School, rated among the top elementary schools in the state of California.

Las Lomitas is technically a public school, although its main support comes from a lavish parent-funded foundation that last year alone raised $2.8 million. “It’s going for $3 million this year,” Berkey said. “For the parents, it’s an attractive tax write-off. We can do good and feel good at the same time, because it benefits our own children.” Also not to be missed was the Menlo Circus Club (initiation fee: $250,000), featuring daily tennis, Friday polo matches, and state-of-the-art stables for horse people who can’t afford or don’t want to be bothered with the ranch-size spreads of owners who stable their own horses, farther up into the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains.

by Charlotte Allen, Weekly Standard | Read more:

Image: Thomas Fluharty

Atherton, Calif. "If you live here, you’ve made it,” David Berkey said to me as I rode shotgun in his car two months ago through the Silicon Valley’s wealth belt. The massive house toward which he was pointing belongs to Sergey Brin, cofounder of Google. With a net worth of $24 billion, Brin is Silicon Valley’s third-richest denizen and the fourteenth-richest man in America, according to Forbes. Berkey was chauffeuring me down Atherton Avenue, a wide, straight, completely tree-lined boulevard nicely bifurcating the city of Atherton (population 7,200), located 29 miles south of San Francisco, boasting no commercial real estate, and with a zip code (94027) that was recently listed by Forbes as America’s most expensive.

Atherton, Calif. "If you live here, you’ve made it,” David Berkey said to me as I rode shotgun in his car two months ago through the Silicon Valley’s wealth belt. The massive house toward which he was pointing belongs to Sergey Brin, cofounder of Google. With a net worth of $24 billion, Brin is Silicon Valley’s third-richest denizen and the fourteenth-richest man in America, according to Forbes. Berkey was chauffeuring me down Atherton Avenue, a wide, straight, completely tree-lined boulevard nicely bifurcating the city of Atherton (population 7,200), located 29 miles south of San Francisco, boasting no commercial real estate, and with a zip code (94027) that was recently listed by Forbes as America’s most expensive.You couldn’t really see Brin’s house from the car, though—just a swatch of rooftop, maybe a chimney—because the point of the trees lining Atherton Avenue and nearly every other street in Atherton is to hide the dwellings behind them. Where the screens of trees happen to thin, property owners have constructed high hedges, high wooden fences, and high brick walls, so that when you look down Atherton Avenue from the Santa Cruz Mountains to the west toward the commuter railroad station to the east, you see only the allée of trees—pine, palms, eucalyptus, sycamore, and juniper—shades of gray-green and brown-green shimmering placidly in the early autumn sun. “This is the Champs-Élysées of Atherton,” Berkey explained. The other thing we didn’t see from Berkey’s car is people, except for the occasional driver on the road.

Turning corners, we drove past other fancy and half-hidden real estate owned by other Silicon Valley grandees; Sheryl Sandberg, the COO of Facebook, and her husband David Goldberg, the CEO of SurveyMonkey, have a 7,200-square-foot house somewhere in the hedge maze. Before there was such a thing as Silicon Valley—that is to say, 40 years ago—Atherton was an affluent bedroom town for white-shoe law-firm partners and Old Economy executives who liked to ride the Southern Pacific Peninsula to their jobs in San Francisco, imitating their East Coast counterparts who rolled on the Hartford-New Haven line from the Southern Connecticut Gold Coast into Manhattan. That was before today’s hiding-the-house custom, and the executives’ front lawns surged out like green carpets to Atherton Avenue and its side streets. Now, Atherton is mostly teardowns and brand new mega-mansions—or at least as mega as their owners can get away with, given Atherton’s highly restrictive zoning laws that mandate enormous lot-to-footprint ratios. To increase their overall square footage, Atherton’s new breed of homeowners typically tunnel out vast underground extra space—wine cellars and home theaters—beneath their dwellings. The dominant style these days is a fanciful mix of Palladian Neoclassic, Loire Valley château, and Mediterranean villa, spreading out manor-house-style to cover as much ground as the zoning laws allow.

“This was a vacant lot five years ago,” said Berkey as we cruised by one of the spanking new stone-faced Atherton domiciles with its multiple dormers, chimneys, tile-roofed turrets, and columned porticos. “Now it’s worth $5 or $6 million. And this house here—it recently sold for $7 million, $4.4 million more than the asking price.” We passed the Menlo School, tuition $38,000 a year, where the parents pick up their kids in Range Rovers and fly them in private jets to exotic foreign locations for birthday parties. Down the road lay the Sacred Heart School, the Menlo School’s Catholic opposite number, where the tuition is only $34,000 a year. Their feeder is Atherton’s Las Lomitas School, rated among the top elementary schools in the state of California.

Las Lomitas is technically a public school, although its main support comes from a lavish parent-funded foundation that last year alone raised $2.8 million. “It’s going for $3 million this year,” Berkey said. “For the parents, it’s an attractive tax write-off. We can do good and feel good at the same time, because it benefits our own children.” Also not to be missed was the Menlo Circus Club (initiation fee: $250,000), featuring daily tennis, Friday polo matches, and state-of-the-art stables for horse people who can’t afford or don’t want to be bothered with the ranch-size spreads of owners who stable their own horses, farther up into the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains.

by Charlotte Allen, Weekly Standard | Read more:

Image: Thomas Fluharty

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

The Real Sharing Economy Is Booming (And It's Not the One Venture Capitalists Are Cashing In On)

[ed. This makes a lot of sense to me. I'd prefer to see an alternate Farmer's/Gardner's market each summer where people could trade excess produce, flowers, anything really. Not even trade, just put out a few boxes of something that someone might need. Not everything has to be sold or bartered.]

After picking more limes than I’ll ever eat from the tree near my apartment, I log onto Facebook and post about them on the Backyard Fruit Swap group I belong to. Someone offers me passion fruits for the limes, and someone else offers guavas. “What kind of guavas?” I reply. I don’t like pineapple guavas.

After picking more limes than I’ll ever eat from the tree near my apartment, I log onto Facebook and post about them on the Backyard Fruit Swap group I belong to. Someone offers me passion fruits for the limes, and someone else offers guavas. “What kind of guavas?” I reply. I don’t like pineapple guavas.

Compared to the rest of the U.S., my home of San Diego can grow some strange types of fruit. Aside from that, my online exchange is not so odd. Sharing is now in vogue—or perhaps it always was.

In human history, the so-called sharing economy is older than money and capitalism. Before anyone came up with the clever idea of giving set values to bits of metal and paper, people figured out that everyone could benefit by bartering and sharing. Sometimes this took the form of barter. You give me some of the fish you caught and I give you some of my crops. You help me harvest my field and I help you harvest yours. Sometimes it takes the form of gifts, seemingly given altruistically, but almost always returned at some point by a reciprocal gift or favor.

Other times, it could be codified by cultural traditions, as in the case of a dowry given at the time of marriage. Or, a group of people might collaborate on a hunt and share the meat based on a specific protocol: the person who made the kill gets certain cuts of meat, the person whose arrow was used gets other cuts, and others who participated in the hunt might get other portions of the animal.

Today, this age-old system is getting a high-tech makeover, and a lot of media attention from BBC, Marketplace, NPR, the Guardian, and Fast Company. But are the sites and apps getting the attention actually sharing, or just a new way to rent or sell goods and services? (...)

The Really Really Free Market is an in-person form of sharing. Participants are invited to bring things they no longer use to give away and to help themselves to whatever they need for free.

“There's no trade,” explains Marks, “This was a little different concept for me to wrap my head about because I've been to a few different Buy Nothing Day events that were centered around a barter.” But at the Really Really Free Market, you can come and just take things. “We don't want there to be any restrictions—the main purpose is to get usable items into the hands of those that need it. That supersedes any sort of 'you must bring something to take something' ideology. We don't want restrictions placed on it.”

In addition to simply moving goods from those who don’t use them into the hands of those who will, the market wants to create community.

by Jill Richardson, Alternet | Read more:

Image: Shutterstock.com/ Ivelin Radkov

Why “Simple” Websites Are Scientifically Better

In a study by Google in August of 2012, researchers found that not only will users judge websites as beautiful or not within 1/50th – 1/20th of a second, but also that “visually complex” websites are consistently rated as less beautiful than their simpler counterparts

Moreover, “highly prototypical” sites – those with layouts commonly associated with sites of it’s category – with simple visual design were rated as the most beautiful across the board.

In other words, the study found the simpler the design, the better.

But why?

In this article, we’ll examine why things like cognitive fluency and visual information processing theory can play a critical role in simplifying your web design & how a simpler design could lead to more conversions.

We’ll also look at a few case studies of sites that simplified their design, and how it improved their conversion rate, as well as give a few pointers to simplify your own design.

What is a Prototypical Website?

If I said “furniture” what image pops up in your mind? If you’re like 95% of people, you think of a chair. If I ask what color represents “boy” you think “blue”, girl = pink, car = sedan, bird = robin, etc.

Prototypicality is the basic mental image your brain creates to categorize everything you interact with. From furniture to websites, your brain has created a template for how things should look and feel.

Online, prototypicality breaks down into smaller categories. You have a different, but specific mental image for social networks, e-commerce sites, and blogs – and if any of those particular websites are missing something from your mental image, you reject the site on conscious and subconscious levels.

If I said “furniture” what image pops up in your mind? If you’re like 95% of people, you think of a chair. If I ask what color represents “boy” you think “blue”, girl = pink, car = sedan, bird = robin, etc.

Prototypicality is the basic mental image your brain creates to categorize everything you interact with. From furniture to websites, your brain has created a template for how things should look and feel.

Online, prototypicality breaks down into smaller categories. You have a different, but specific mental image for social networks, e-commerce sites, and blogs – and if any of those particular websites are missing something from your mental image, you reject the site on conscious and subconscious levels.

by Peep Laja, ConversionXL | Read more:

Image: Alexandre Normand (skippjon) on FlickrCancer Meets its Nemesis in Reprogrammed Blood Cells

"The results are holding up very nicely." Cancer researcher Michel Sadelain is admirably understated about the success of a treatment developed in his lab at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

In March, he announced that five people with a type of blood cancer called acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) were in remission following treatment with genetically engineered immune cells from their own blood. One person's tumours disappeared in just eight days.

Sadelain has now told New Scientist that a further 11 people have been treated, almost all of them with the same outcome. Several trials for other cancers are also showing promise.

What has changed is that researchers are finding ways to train the body's own immune system to kill cancer cells. Until now, the most common methods of attacking cancer use drugs or radiation, which have major side effects and are blunt instruments to say the least.

The latest techniques involve genetically engineering immune T-cells to target and kill cancer cells, while leaving healthy cells relatively unscathed.

T-cells normally travel around the body clearing sickly or infected cells. Cancer cells can sometimes escape their attention by activating receptors on their surface that tell T-cells not to attack. ALL affects another type of immune cell, the B-cells, so Sadelain takes T-cells from people with ALL and modifies them to recognise CD19, a surface protein on all B-cells – whether cancerous or healthy. After being injected back into the patient, the reprogrammed T-cells destroy all B-cells in the person's body. This means they need bone marrow transplants afterwards to rebuild their immune systems. But because ALL affects only B-cells, the therapy guarantees that all the cancerous cells are destroyed.

by Andy Coghlan, New Scientist | Read more:

Image: Steve Gscheissner/Science Photo Library

In March, he announced that five people with a type of blood cancer called acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) were in remission following treatment with genetically engineered immune cells from their own blood. One person's tumours disappeared in just eight days.

Sadelain has now told New Scientist that a further 11 people have been treated, almost all of them with the same outcome. Several trials for other cancers are also showing promise.

What has changed is that researchers are finding ways to train the body's own immune system to kill cancer cells. Until now, the most common methods of attacking cancer use drugs or radiation, which have major side effects and are blunt instruments to say the least.

The latest techniques involve genetically engineering immune T-cells to target and kill cancer cells, while leaving healthy cells relatively unscathed.

T-cells normally travel around the body clearing sickly or infected cells. Cancer cells can sometimes escape their attention by activating receptors on their surface that tell T-cells not to attack. ALL affects another type of immune cell, the B-cells, so Sadelain takes T-cells from people with ALL and modifies them to recognise CD19, a surface protein on all B-cells – whether cancerous or healthy. After being injected back into the patient, the reprogrammed T-cells destroy all B-cells in the person's body. This means they need bone marrow transplants afterwards to rebuild their immune systems. But because ALL affects only B-cells, the therapy guarantees that all the cancerous cells are destroyed.

by Andy Coghlan, New Scientist | Read more:

Image: Steve Gscheissner/Science Photo Library

In Silicon Valley, Partying Like It’s 1999

These are fabulous times in Silicon Valley.

Mere youths, who in another era would just be graduating from college or perhaps wondering what to make of their lives, are turning down deals that would make them and their great-grandchildren wealthy beyond imagining. They are confident that even better deals await.

“Man, it feels more and more like 1999 every day,” tweeted Bill Gurley, one of the valley’s leading venture capitalists. “Risk is being discounted tremendously.”

That was in May, shortly after his firm, Benchmark, led a $13.5 million investment in Snapchat, the disappearing-photo site that has millions of adolescent users but no revenue.

Snapchat, all of two years old, just turned down a multibillion-dollar deal from Facebook and, perhaps, an even bigger deal from Google. On paper, that would mean a fortyfold return on Benchmark’s investment in less than a year.

Benchmark is the venture capital darling of the moment, a backer not only of Snapchat but the photo-sharing app Instagram (sold for $1 billion to Facebook), the ride-sharing service Uber (valued at $3.5 billion) and Twitter ($22 billion), among many others. Ten of its companies have gone public in the last two years, with another half-dozen on the way. Benchmark seems to have a golden touch.

That is generating a huge amount of attention and an undercurrent of concern. In Silicon Valley, it may not be 1999 yet, but that fateful year — a moment when no one thought there was any risk to the wildest idea — can be seen on the horizon, drifting closer.

Mere youths, who in another era would just be graduating from college or perhaps wondering what to make of their lives, are turning down deals that would make them and their great-grandchildren wealthy beyond imagining. They are confident that even better deals await.

“Man, it feels more and more like 1999 every day,” tweeted Bill Gurley, one of the valley’s leading venture capitalists. “Risk is being discounted tremendously.”

That was in May, shortly after his firm, Benchmark, led a $13.5 million investment in Snapchat, the disappearing-photo site that has millions of adolescent users but no revenue.

Snapchat, all of two years old, just turned down a multibillion-dollar deal from Facebook and, perhaps, an even bigger deal from Google. On paper, that would mean a fortyfold return on Benchmark’s investment in less than a year.

Benchmark is the venture capital darling of the moment, a backer not only of Snapchat but the photo-sharing app Instagram (sold for $1 billion to Facebook), the ride-sharing service Uber (valued at $3.5 billion) and Twitter ($22 billion), among many others. Ten of its companies have gone public in the last two years, with another half-dozen on the way. Benchmark seems to have a golden touch.

That is generating a huge amount of attention and an undercurrent of concern. In Silicon Valley, it may not be 1999 yet, but that fateful year — a moment when no one thought there was any risk to the wildest idea — can be seen on the horizon, drifting closer.

by David Streitfeld, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Dan Taylor for TechcrunchTuesday, November 26, 2013

Dealer's Hand

Very important people line up differently from you and me. They don’t want to stand behind anyone else, or to acknowledge wanting something that can’t immediately be had. If there’s a door they’re eager to pass through, and hundreds of equally or even more important people are there, too, they get as close to the door as they can, claim a patch of available space as though it had been reserved for them, and maintain enough distance to pretend that they are not in a line.

Prior to the official opening of Art Basel, the annual fair in Switzerland, there is a two-day V.I.P. preview. In many respects, the preview is the fair. It’s when the collectors who can afford the good stuff are allowed in to buy it. After those two days, there isn’t much left for sale, and it becomes less a fair than a kind of pop-up museum, as the V.I.P.s, many of whom have come to Basel from the Biennale in Venice, continue on, perhaps to London for the auctions there. The international art circuit can be gruelling, which is why pretty much everyone who participates in it takes off the month of August, to recuperate.

Prior to the official opening of Art Basel, the annual fair in Switzerland, there is a two-day V.I.P. preview. In many respects, the preview is the fair. It’s when the collectors who can afford the good stuff are allowed in to buy it. After those two days, there isn’t much left for sale, and it becomes less a fair than a kind of pop-up museum, as the V.I.P.s, many of whom have come to Basel from the Biennale in Venice, continue on, perhaps to London for the auctions there. The international art circuit can be gruelling, which is why pretty much everyone who participates in it takes off the month of August, to recuperate.

The Basel preview began at 11 a.m. on a Tuesday in June. The meat of the fair was in a gigantic convention center on the east side of the Rhine. The dealers’ booths were arrayed along two vast rectangular grids, which enclosed a circular courtyard that resembled a panopticon. The fair occupied two floors. The bottom one featured blue-chip art, offered by the powerhouse dealers; Picassos and Warhols could be seen among more contemporary work. Upstairs, for the most part, was younger work, exhibited by smaller galleries.

On the morning of the preview, after a champagne breakfast in the panopticon, the V.I.P.s gathered at the doors, under the watchful eye of guards in berets and dark crewneck sweaters. Through a window in the door, you could see, down the hall, the dealer David Zwirner, with his sales staff huddled around him, as though for a pep talk. The Zwirner booth was just past the Fondation Beyeler’s. (The Swiss dealer Ernst Beyeler, who died in 2010, was one of Art Basel’s founders and its presiding spirit.) Zwirner comes in force: he had about a dozen salespeople with him, a mixture of partners, directors, and associates, as well as a platoon of assistants and art handlers. A few minutes before the doors opened, they took up positions in a sales-floor spread defense. Bellatrix Hubert, a Zwirner partner, pantomimed a gesture of being slammed by an incoming flood. The doors parted, and the buyers poured in. (...)

“One of the reasons there’s so much talk about money is that it’s so much easier to talk about than the art,” Zwirner told me one day. You meet a lot of people in the art world who are exhausted and dismayed by the focus on money, and by its dominance. It distracts from the work, they say. It distorts curatorial instincts, critical appraisals, and young artists’ careers. It scares away civilians, who begin to lump art in with other symptoms of excess and dismiss it as another garish plaything of the rich. Of course, many of those who complain—dealers, artists, curators—are complicit. The culture industry, which supports them in one way or another, and which hardly existed a generation ago, subsists on all that money—mostly on the largesse and folly of wealthy art lovers, whether their motivations are lofty or base.

Since the doldrums of the early nineties, the market for contemporary art, which has various definitions (work created after the Second World War, or during “our” lifetime, or post-1960, or post-1970), has rocketed up, year after year, flattening out briefly amid the financial crisis and global recession of 2008-09, before resuming its climb. Big annual returns have attracted more people to buying art, which has raised prices further. It is no coincidence that this steep rise, in recent decades, coincides with the increasing financialization of the world economy. The accumulation of greater wealth in the hands of a smaller percentage of the world’s population has created immense fortunes with a limitless capacity to pursue a limited supply of art work. The globalization of the art market—the interest in contemporary art among newly wealthy Asians, Latin Americans, Arabs, and Russians—has furnished it with scores of new buyers, and perhaps fresh supplies of greater fools. Once you have hundreds of millions of dollars, it’s hard to know where to put it all. Art is transportable, unregulated, glamorous, arcane, beautiful, difficult. It is easier to store than oil, more esoteric than diamonds, more durable than political influence. Its elusive valuation makes it conducive to extremely creative tax accounting.

“These are the highest-luxury goods man has ever known,” a dealer told me. “If you’re in the business of selling art, you’re an idiot if you don’t respond to that.”

The Basel preview began at 11 a.m. on a Tuesday in June. The meat of the fair was in a gigantic convention center on the east side of the Rhine. The dealers’ booths were arrayed along two vast rectangular grids, which enclosed a circular courtyard that resembled a panopticon. The fair occupied two floors. The bottom one featured blue-chip art, offered by the powerhouse dealers; Picassos and Warhols could be seen among more contemporary work. Upstairs, for the most part, was younger work, exhibited by smaller galleries.

On the morning of the preview, after a champagne breakfast in the panopticon, the V.I.P.s gathered at the doors, under the watchful eye of guards in berets and dark crewneck sweaters. Through a window in the door, you could see, down the hall, the dealer David Zwirner, with his sales staff huddled around him, as though for a pep talk. The Zwirner booth was just past the Fondation Beyeler’s. (The Swiss dealer Ernst Beyeler, who died in 2010, was one of Art Basel’s founders and its presiding spirit.) Zwirner comes in force: he had about a dozen salespeople with him, a mixture of partners, directors, and associates, as well as a platoon of assistants and art handlers. A few minutes before the doors opened, they took up positions in a sales-floor spread defense. Bellatrix Hubert, a Zwirner partner, pantomimed a gesture of being slammed by an incoming flood. The doors parted, and the buyers poured in. (...)

“One of the reasons there’s so much talk about money is that it’s so much easier to talk about than the art,” Zwirner told me one day. You meet a lot of people in the art world who are exhausted and dismayed by the focus on money, and by its dominance. It distracts from the work, they say. It distorts curatorial instincts, critical appraisals, and young artists’ careers. It scares away civilians, who begin to lump art in with other symptoms of excess and dismiss it as another garish plaything of the rich. Of course, many of those who complain—dealers, artists, curators—are complicit. The culture industry, which supports them in one way or another, and which hardly existed a generation ago, subsists on all that money—mostly on the largesse and folly of wealthy art lovers, whether their motivations are lofty or base.

Since the doldrums of the early nineties, the market for contemporary art, which has various definitions (work created after the Second World War, or during “our” lifetime, or post-1960, or post-1970), has rocketed up, year after year, flattening out briefly amid the financial crisis and global recession of 2008-09, before resuming its climb. Big annual returns have attracted more people to buying art, which has raised prices further. It is no coincidence that this steep rise, in recent decades, coincides with the increasing financialization of the world economy. The accumulation of greater wealth in the hands of a smaller percentage of the world’s population has created immense fortunes with a limitless capacity to pursue a limited supply of art work. The globalization of the art market—the interest in contemporary art among newly wealthy Asians, Latin Americans, Arabs, and Russians—has furnished it with scores of new buyers, and perhaps fresh supplies of greater fools. Once you have hundreds of millions of dollars, it’s hard to know where to put it all. Art is transportable, unregulated, glamorous, arcane, beautiful, difficult. It is easier to store than oil, more esoteric than diamonds, more durable than political influence. Its elusive valuation makes it conducive to extremely creative tax accounting.

“These are the highest-luxury goods man has ever known,” a dealer told me. “If you’re in the business of selling art, you’re an idiot if you don’t respond to that.”

by Nick Paumgarten, New Yorker | Read more:

Image: Pari DukovicBlame Rich, Overeducated Elites as Our Society Frays

Analysis of past societies shows that these destabilizing historical trends develop slowly, last many decades, and are slow to subside. The Roman Empire, Imperial China and medieval and early-modern England and France suffered such cycles, to cite a few examples. In the U.S., the last long period of instability began in the 1850s and lasted through the Gilded Age and the “violent 1910s.”

We now see the same forces in the contemporary U.S. Of about 30 detailed indicators I developed for tracing these historical cycles (reflecting popular well-being, inequality, social cooperation and its inverse, polarization and conflict), almost all have been moving in the wrong direction in the last three decades.

The roots of the current American predicament go back to the 1970s, when wages of workers stopped keeping pace with their productivity. The two curves diverged: Productivity continued to rise, as wages stagnated. The “great divergence” between the fortunes of the top 1 percent and the other 99 percent is much discussed, yet its implications for long-term political disorder are underappreciated. Battles such as the recent government shutdown are only one manifestation of what is likely to be a decade-long period.

Wealth Disrupts

How does growing economic inequality lead to political instability? Partly this correlation reflects a direct, causal connection. High inequality is corrosive of social cooperation and willingness to compromise, and waning cooperation means more discord and political infighting. Perhaps more important, economic inequality is also a symptom of deeper social changes, which have gone largely unnoticed.

Increasing inequality leads not only to the growth of top fortunes; it also results in greater numbers of wealth-holders. The “1 percent” becomes “2 percent.” Or even more. There are many more millionaires, multimillionaires and billionaires today compared with 30 years ago, as a proportion of the population.

Let’s take households worth $10 million or more (in 1995 dollars). According to the research by economist Edward Wolff, from 1983 to 2010 the number of American households worth at least $10 million grew to 350,000 from 66,000.

Rich Americans tend to be more politically active than the rest of the population. They supportcandidates who share their views and values; they sometimes run for office themselves. Yet the supply of political offices has stayed flat (there are still 100 senators and 435 representatives -- the same numbers as in 1970). In technical terms, such a situation is known as “elite overproduction.”

A related sign is the overproduction of law degrees. From the mid-1970s to 2011, according to the American Bar Association, the number of lawyers tripled to 1.2 million from 400,000. Meanwhile, the population grew by only 45 percent. Economic Modeling Specialists Intl. recently estimated that twice as many law graduates pass the bar exam as there are job openings for them. In other words, every year U.S. law schools churn out about 25,000 “surplus” lawyers, many of whom are in debt. A large number of them go to law school with an ambition to enter politics someday.

Don’t hate them for it -- they are at the mercy of the same large, impersonal social forces as the rest of us. The number of newly minted MBAs has expanded even faster than law degrees.

How does growing economic inequality lead to political instability? Partly this correlation reflects a direct, causal connection. High inequality is corrosive of social cooperation and willingness to compromise, and waning cooperation means more discord and political infighting. Perhaps more important, economic inequality is also a symptom of deeper social changes, which have gone largely unnoticed.