Friday, February 28, 2014

The Great Crypto Stagecoach Robbery

[ed. See also: Mt. Gox Topples.]

Mt. Gox was the first big Bitcoin exchange; as such it attracted the most attention, the most traffic, and the most trouble. It was hacked repeatedly because, at one time, it was simply where all the Bitcoins were. Most knowledgeable Bitcoin enthusiasts took off for more modern, more reliable exchanges long ago. (...)

Mt. Gox CEO Mark Karpeles, who is apparently holed up at home in Tokyo with his cat, has since verified in an IRC chat that the document is "more or less" legitimate, though it was not prepared internally by his embattled firm. He says that he is still trying to save the company: "'Giving up' is not part of how I usually do things."

You could look at the Mt. Gox disaster this way: imagine that ordinary consumer banks had only just been invented five years ago, and they'd since exploded in popularity. All of a sudden, Bank of America's internal systems are alleged to have been broken all along and every penny that was held there is gone. The money in all the other banks is okay, seemingly—but now, the whole banking system looks very rocky and untrustworthy. How to trust any bank, if one of the biggest lost everything?

That's basically what has happened to Bitcoin over the last few weeks, since it became clear that Mt. Gox was having trouble processing transactions last November. (...)

There has been a temptation to mock the libertarians who make up a lot of Bitcoin's most passionate following, and to blame the unregulated joys of the free market for Bitcoin's current problems. But just take a look at the stock market, the startup world, the bankruptcy courts, the markets for distressed debt, the art market, the real estate market, and any number of other markets (sure, basically all of them) where hopeful neophytes ripe for the plucking and clever participants eager to benefit from insider knowledge, plus quite a lot of plain cheats, are not hard to find. The most surprising thing about the Mt. Gox episode so far might be the resilience of Bitcoin prices, which might have been expected to take a much larger tumble in the face of the disaster.

by Maria Bustillos, The Awl | Read more:

Image: uncredited

An Unthinkably Modern Miracle

A cursory internet search revealed a world of theories and testimonials on how to negotiate medical bills, but all of the articles and listicles and forums effectively boiled down to two distinct approaches. The first and most obvious was to simply claim I couldn’t pay. So long as I could credibly explain the nature of my hardship, chances were good that the hospital would offer me a discount. The second approach was more aggressive and involved obtaining copies of the hospital’s billing forms. I would have more leverage if I could find a billing mistake or could pick at one of the more extreme charges. Just be warned, one website cautioned, hospitals won’t be very friendly about this.

I opted for the former strategy, dialing the 800 number on my bill. This connected me with a pleasant-sounding woman in what I realized was not a hospital office but a call center. Before I could say anything, she politely reiterated the active balance on my account.

I opted for the former strategy, dialing the 800 number on my bill. This connected me with a pleasant-sounding woman in what I realized was not a hospital office but a call center. Before I could say anything, she politely reiterated the active balance on my account.

“I’d like to discuss my options,” I said. “This surgery resulted in complications that prevented me from working for six weeks, and that’s been very difficult financially.”

“We’d be happy to help, Mr. Fischer. What we can offer you is an installment plan.”

“That’s great,” I said, trying to smile through the phone. “But I hoped we might be able to talk about a discount for prompt payment.”

“I’m sorry, I’m not authorized to offer that,” she said.

“Not a problem. Could I speak to your supervisor about the matter?”

“He’s not available, sir,” she said.

I asked her when he might be and she suggested I call back next week. So I did. And although I reached a different operator, I had the exact same conversation. This time I also asked for an itemized list of charges, which was a buzz-term I’d picked up from the medical negotiation how-tos.

“That should be what’s on your bill,” the second operator said.

“My bill only has category charges. I’m trying to get an itemized breakdown of what those are for.”

The operator said he’d send one out. What reached me several days later was an identical copy of my bill.

Additional research produced mention of a form called the UB-04. Evidently, this document was used by hospitals as the central manifest for billing my insurance provider. Get the UB-04 form—said the patients’ rights message boards—and you’ll get the true dollar amounts associated with your treatment.

A call to the hospital’s medical records department redirected me to their billing office. After a few minutes of hold music, an operator informed me in no uncertain terms that UB-04 forms were not given to patients.

“For insurance only,” she said, and hustled me off the line.

My insurance company said that they didn’t have access to it either, but that the hospital should give it to me.

Technically speaking, the UB-04 form is part of something called the HIPAA Designated Records Set. HIPAA (the Healthcare Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) is an enormous piece of Clinton-era legislation that has a lot to do with patient privacy. You sign a HIPAA disclosure every time you visit a new doctor, allowing them to legally share your medical records with your insurer. But the “P” in the acronym also has more specific consumer-protection benefits. It legally establishes patients’ rights to access any document used to make decisions about their treatment, billing, or insurance payments.

Armed with this information, I again called the billing department. I reached another operator. When she told me that the UB-04 form was off-limits, I hit her with the HIPAA statue and code.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” she said, audibly annoyed. “Can you fax me whatever you’re reading from?”

“I’m legally entitled to this form,” I said. “This is my right as a patient. May I speak to your supervisor?” By this point I was keeping a record of every phone call, every response, everyone’s name.

“He’s on special assignment and not available,” the woman said.

“Can I have your name?”

She offered her first name as Ariel, but wouldn’t give a last name.

“Can I have your supervisor’s name and contact information, then?”

Ariel asked me to hold while she transferred me to someone who could better assist with my request. It took me a moment to realize that the transfer was actually just her hanging up.

I opted for the former strategy, dialing the 800 number on my bill. This connected me with a pleasant-sounding woman in what I realized was not a hospital office but a call center. Before I could say anything, she politely reiterated the active balance on my account.

I opted for the former strategy, dialing the 800 number on my bill. This connected me with a pleasant-sounding woman in what I realized was not a hospital office but a call center. Before I could say anything, she politely reiterated the active balance on my account.“I’d like to discuss my options,” I said. “This surgery resulted in complications that prevented me from working for six weeks, and that’s been very difficult financially.”

“We’d be happy to help, Mr. Fischer. What we can offer you is an installment plan.”

“That’s great,” I said, trying to smile through the phone. “But I hoped we might be able to talk about a discount for prompt payment.”

“I’m sorry, I’m not authorized to offer that,” she said.

“Not a problem. Could I speak to your supervisor about the matter?”

“He’s not available, sir,” she said.

I asked her when he might be and she suggested I call back next week. So I did. And although I reached a different operator, I had the exact same conversation. This time I also asked for an itemized list of charges, which was a buzz-term I’d picked up from the medical negotiation how-tos.

“That should be what’s on your bill,” the second operator said.

“My bill only has category charges. I’m trying to get an itemized breakdown of what those are for.”

The operator said he’d send one out. What reached me several days later was an identical copy of my bill.

Additional research produced mention of a form called the UB-04. Evidently, this document was used by hospitals as the central manifest for billing my insurance provider. Get the UB-04 form—said the patients’ rights message boards—and you’ll get the true dollar amounts associated with your treatment.

A call to the hospital’s medical records department redirected me to their billing office. After a few minutes of hold music, an operator informed me in no uncertain terms that UB-04 forms were not given to patients.

“For insurance only,” she said, and hustled me off the line.

My insurance company said that they didn’t have access to it either, but that the hospital should give it to me.

Technically speaking, the UB-04 form is part of something called the HIPAA Designated Records Set. HIPAA (the Healthcare Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) is an enormous piece of Clinton-era legislation that has a lot to do with patient privacy. You sign a HIPAA disclosure every time you visit a new doctor, allowing them to legally share your medical records with your insurer. But the “P” in the acronym also has more specific consumer-protection benefits. It legally establishes patients’ rights to access any document used to make decisions about their treatment, billing, or insurance payments.

Armed with this information, I again called the billing department. I reached another operator. When she told me that the UB-04 form was off-limits, I hit her with the HIPAA statue and code.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” she said, audibly annoyed. “Can you fax me whatever you’re reading from?”

“I’m legally entitled to this form,” I said. “This is my right as a patient. May I speak to your supervisor?” By this point I was keeping a record of every phone call, every response, everyone’s name.

“He’s on special assignment and not available,” the woman said.

“Can I have your name?”

She offered her first name as Ariel, but wouldn’t give a last name.

“Can I have your supervisor’s name and contact information, then?”

Ariel asked me to hold while she transferred me to someone who could better assist with my request. It took me a moment to realize that the transfer was actually just her hanging up.

by John Fischer, TMN | Read more:

Image: Martin Mull

Thursday, February 27, 2014

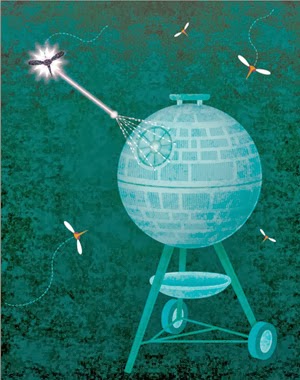

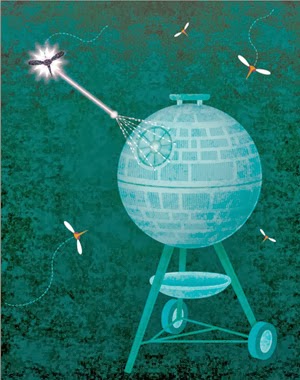

Backyard Star Wars

“So, how would you kill mosquitoes with a laser?”

Nathan Myhrvold asked us. Lowell Wood, Rod Hyde, and I smiled. The three of us were meeting with Myhrvold in the fall of 2006, in an office at Intellectual Ventures Management, a company in Bellevue, Wash., that he founded in 2000 to create and invest in inventions. We smiled because we had just spent the afternoon arguing over that very question, scribbling ideas and calculations on a whiteboard, and had come up with what we thought was a pretty good answer: a “photonic fence” in the form of a row of vertical posts that would use optical sensors and lasers to spot, identify, and zap bad bugs on the wing.

Nathan Myhrvold asked us. Lowell Wood, Rod Hyde, and I smiled. The three of us were meeting with Myhrvold in the fall of 2006, in an office at Intellectual Ventures Management, a company in Bellevue, Wash., that he founded in 2000 to create and invest in inventions. We smiled because we had just spent the afternoon arguing over that very question, scribbling ideas and calculations on a whiteboard, and had come up with what we thought was a pretty good answer: a “photonic fence” in the form of a row of vertical posts that would use optical sensors and lasers to spot, identify, and zap bad bugs on the wing.

The idea of building a high-tech defense against disease-carrying pests had come up in discussions that Myhrvold and Wood had been having with Bill Gates, who was Myhrvold’s boss when he was chief technology officer at Microsoft in the 1990s. Through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Gates has been trying to improve living conditions in some of the world’s poorest countries and in particular to come up with ways to eradicate malaria, a mosquito-borne disease that sickens about a quarter billion people a year and kills nearly a million annually, including roughly 2000 children a day (see Web-only sidebar, “New Techniques Against a Tenacious Disease”).

Wood, a veteran of advanced weapons development at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, in California, and one of the scientists behind the Strategic Defense Initiative (otherwise known as “Star Wars”), had suggested trying a similarly high-tech approach against malarial mosquitoes—to take advantage of inexpensive, low-power sensors and computers to somehow track individual mosquitoes and shoot them out of the air. If it could be done cheaply enough, this might offer the first really new way in many years to combat malaria, as well as other diseases transmitted by flying insects, such as West Nile virus and dengue fever.

Hyde and I had worked with Wood at Livermore. Hyde now manages Intellectual Ventures’ stable of staff and consulting inventors, and he assigned me the challenge of making the idea work—or showing why it couldn’t.

Three years later, my colleagues and I at Intellectual Ventures have now worked out many of the trickiest aspects of the photonic fence and have constructed prototypes that can indeed identify mosquitoes from many meters away, track the bugs in flight, and hit them with debilitating blasts of laser fire. And we did it without a multimillion-dollar grant from some national Department of Entomological Defense. Nearly everything we used can be purchased from standard electronics retailers or online auction sites.

In fact, for a few thousand dollars, a reasonably skilled engineer (such as a typical IEEE Spectrum reader) could probably assemble a version of our fence to shield backyard barbecue parties from voracious mosquitoes. We therefore present the following how-to guide to building a photonic bug killer, in five parts: selecting an appropriate weapon, spotting the bugs, distinguishing friends from foes, getting a pest in your sights, and finally shooting to kill.

Nathan Myhrvold asked us. Lowell Wood, Rod Hyde, and I smiled. The three of us were meeting with Myhrvold in the fall of 2006, in an office at Intellectual Ventures Management, a company in Bellevue, Wash., that he founded in 2000 to create and invest in inventions. We smiled because we had just spent the afternoon arguing over that very question, scribbling ideas and calculations on a whiteboard, and had come up with what we thought was a pretty good answer: a “photonic fence” in the form of a row of vertical posts that would use optical sensors and lasers to spot, identify, and zap bad bugs on the wing.

Nathan Myhrvold asked us. Lowell Wood, Rod Hyde, and I smiled. The three of us were meeting with Myhrvold in the fall of 2006, in an office at Intellectual Ventures Management, a company in Bellevue, Wash., that he founded in 2000 to create and invest in inventions. We smiled because we had just spent the afternoon arguing over that very question, scribbling ideas and calculations on a whiteboard, and had come up with what we thought was a pretty good answer: a “photonic fence” in the form of a row of vertical posts that would use optical sensors and lasers to spot, identify, and zap bad bugs on the wing.The idea of building a high-tech defense against disease-carrying pests had come up in discussions that Myhrvold and Wood had been having with Bill Gates, who was Myhrvold’s boss when he was chief technology officer at Microsoft in the 1990s. Through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Gates has been trying to improve living conditions in some of the world’s poorest countries and in particular to come up with ways to eradicate malaria, a mosquito-borne disease that sickens about a quarter billion people a year and kills nearly a million annually, including roughly 2000 children a day (see Web-only sidebar, “New Techniques Against a Tenacious Disease”).

Wood, a veteran of advanced weapons development at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, in California, and one of the scientists behind the Strategic Defense Initiative (otherwise known as “Star Wars”), had suggested trying a similarly high-tech approach against malarial mosquitoes—to take advantage of inexpensive, low-power sensors and computers to somehow track individual mosquitoes and shoot them out of the air. If it could be done cheaply enough, this might offer the first really new way in many years to combat malaria, as well as other diseases transmitted by flying insects, such as West Nile virus and dengue fever.

Hyde and I had worked with Wood at Livermore. Hyde now manages Intellectual Ventures’ stable of staff and consulting inventors, and he assigned me the challenge of making the idea work—or showing why it couldn’t.

Three years later, my colleagues and I at Intellectual Ventures have now worked out many of the trickiest aspects of the photonic fence and have constructed prototypes that can indeed identify mosquitoes from many meters away, track the bugs in flight, and hit them with debilitating blasts of laser fire. And we did it without a multimillion-dollar grant from some national Department of Entomological Defense. Nearly everything we used can be purchased from standard electronics retailers or online auction sites.

In fact, for a few thousand dollars, a reasonably skilled engineer (such as a typical IEEE Spectrum reader) could probably assemble a version of our fence to shield backyard barbecue parties from voracious mosquitoes. We therefore present the following how-to guide to building a photonic bug killer, in five parts: selecting an appropriate weapon, spotting the bugs, distinguishing friends from foes, getting a pest in your sights, and finally shooting to kill.

by Jordin Kare, IEEE Spectrum | Read more:

Image: Jude BuffumAll About Eve—and Then Some

Imagine, for a second, this:

It’s 1959. You’re a girl, 15 years old. Your parents are bohemians before the category becomes a fashionable one. Your dad, Sol, born in Brooklyn, is first violinist for the Twentieth Century Fox Orchestra. First violinist for the Los Angeles Philharmonic too, and a Fulbright scholar. He once got into a fistfight over the proper way to play the dotted notes in Bach. Your mom, Mae, is an artist. A work of art, as well, so beautiful is she, and charming. Your godfather is Igor Stravinsky. He’s been slipping you glasses of scotch under the table since you turned 13, and his wife, the peerlessly elegant Vera, taught you how to eat caviar. Your house, on the corner of Cheremoya and Chula Vista at the foot of the Hollywood Hills, is always full-to-bursting with your dad’s hip musician friends: Jelly Roll Morton and Stuff Smith, Joseph Szigeti and Marilyn Horne. There are tales of earlier picnics along the L.A. River with Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard, Greta Garbo, Bertrand Russell, and the Huxleys. The two Kenneths, Rexroth and Patchen, perform readings in your living room regularly. But poetry bores you blind, so you talk Lucy Herrmann, wife of movie composer Bernard—Bennie to you—into telling you stories upstairs. Arnold Schoenberg just laughs when you and your sister, Mirandi, get stuck together with bubble gum in the middle of the premiere of his latest piece at the Ojai Music Festival.

It’s 1959. You’re a girl, 15 years old. Your parents are bohemians before the category becomes a fashionable one. Your dad, Sol, born in Brooklyn, is first violinist for the Twentieth Century Fox Orchestra. First violinist for the Los Angeles Philharmonic too, and a Fulbright scholar. He once got into a fistfight over the proper way to play the dotted notes in Bach. Your mom, Mae, is an artist. A work of art, as well, so beautiful is she, and charming. Your godfather is Igor Stravinsky. He’s been slipping you glasses of scotch under the table since you turned 13, and his wife, the peerlessly elegant Vera, taught you how to eat caviar. Your house, on the corner of Cheremoya and Chula Vista at the foot of the Hollywood Hills, is always full-to-bursting with your dad’s hip musician friends: Jelly Roll Morton and Stuff Smith, Joseph Szigeti and Marilyn Horne. There are tales of earlier picnics along the L.A. River with Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard, Greta Garbo, Bertrand Russell, and the Huxleys. The two Kenneths, Rexroth and Patchen, perform readings in your living room regularly. But poetry bores you blind, so you talk Lucy Herrmann, wife of movie composer Bernard—Bennie to you—into telling you stories upstairs. Arnold Schoenberg just laughs when you and your sister, Mirandi, get stuck together with bubble gum in the middle of the premiere of his latest piece at the Ojai Music Festival.

Now imagine this:

You’re a sophomore at Hollywood High. It’s that dead time between classes and you’re in the girls’ room, smoking one of the 87 cigarettes you share daily with Sally. Sally, who before she even transferred to Hollywood High had been through the wringer at Twentieth Century Fox, signed to a contract and then summarily dropped because she’d bleached her hair an eyeball-scorching shade of platinum the night before she was supposed to report for her first day of work, rendering herself superfluous because, unbeknownst to her, the studio had been planning to make her the next natural-type beauty in the Jean Seberg mold. Sally, who finds mornings so onerous she has to chase 15 milligrams of Dexamyl with four cups of thin coffee just to drag herself to first period. Sally, who is rich and surly and sex-savvy and has recently been taken up by a group of twenty-somethings from her acting class, the Thunderbird Girls you call them, if only in your head, knockouts all, cruising around town in—what else?—Thunderbird convertibles, spending their nights on the Sunset Strip, their weekends in Palm Springs with the ring-a-ding likes of Frank Sinatra. Sally, who is your best friend.

The company you keep is fast, which is O.K. by you since fast, as it so happens, is just your speed. No woof-woof among sex kittens you. Not with your perfect skin and teeth, hair the color of vanilla ice cream, secondary sexual characteristics that are second to none. The year before, when you were 14, you went to a party you weren’t supposed to go to. A right kind of wrong guy—an Adult Male, a big beef dreamboat galoot, just what you’d had in mind when you sneaked out of the house—told you he’d give you a ride home. You jumped at the offer. But when you lost your nerve, confessed your age, he pulled the car over to the side of the road. “Don’t let guys pick you up like this, kid—you might get hurt,” he said, undercutting this gruff bit of fatherly advice by laying a five-alarm kiss on you. He drove off without telling you his name. A few months passed and there was your white knight in black-and-white, on the front page of every paper in town. He’d had a run-in with another under-age girl, only this encounter had ended in penetration: her knife in his gut. Johnny Stompanato, henchman of Mob boss Mickey Cohen, dead at the hands of the 14-year-old daughter of his squeeze, Lana Turner. Tough luck for Johnny, but a good sign for you: you caught the eye of the guy who took off the Sweater Girl’s sweater nightly. If that doesn’t make you a movie star yourself it puts you in the same firmament as one, doesn’t it? At the very least it makes you seriously hot stuff.

And you’ve got more than looks going for you. You’ve got brains too. You read all the time—Proust, Woolf, Colette, Anthony Powell. And you’re good at school, even if you spend most of your class time doodling Frederick’s of Hollywood models on the back of your notebook. You certainly have no intention of making a right turn on Sunset after graduation, moving up the road to U.C.L.A., in squarer-than-square Westwood.

It’s 1959. You’re a girl, 15 years old. Your parents are bohemians before the category becomes a fashionable one. Your dad, Sol, born in Brooklyn, is first violinist for the Twentieth Century Fox Orchestra. First violinist for the Los Angeles Philharmonic too, and a Fulbright scholar. He once got into a fistfight over the proper way to play the dotted notes in Bach. Your mom, Mae, is an artist. A work of art, as well, so beautiful is she, and charming. Your godfather is Igor Stravinsky. He’s been slipping you glasses of scotch under the table since you turned 13, and his wife, the peerlessly elegant Vera, taught you how to eat caviar. Your house, on the corner of Cheremoya and Chula Vista at the foot of the Hollywood Hills, is always full-to-bursting with your dad’s hip musician friends: Jelly Roll Morton and Stuff Smith, Joseph Szigeti and Marilyn Horne. There are tales of earlier picnics along the L.A. River with Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard, Greta Garbo, Bertrand Russell, and the Huxleys. The two Kenneths, Rexroth and Patchen, perform readings in your living room regularly. But poetry bores you blind, so you talk Lucy Herrmann, wife of movie composer Bernard—Bennie to you—into telling you stories upstairs. Arnold Schoenberg just laughs when you and your sister, Mirandi, get stuck together with bubble gum in the middle of the premiere of his latest piece at the Ojai Music Festival.

It’s 1959. You’re a girl, 15 years old. Your parents are bohemians before the category becomes a fashionable one. Your dad, Sol, born in Brooklyn, is first violinist for the Twentieth Century Fox Orchestra. First violinist for the Los Angeles Philharmonic too, and a Fulbright scholar. He once got into a fistfight over the proper way to play the dotted notes in Bach. Your mom, Mae, is an artist. A work of art, as well, so beautiful is she, and charming. Your godfather is Igor Stravinsky. He’s been slipping you glasses of scotch under the table since you turned 13, and his wife, the peerlessly elegant Vera, taught you how to eat caviar. Your house, on the corner of Cheremoya and Chula Vista at the foot of the Hollywood Hills, is always full-to-bursting with your dad’s hip musician friends: Jelly Roll Morton and Stuff Smith, Joseph Szigeti and Marilyn Horne. There are tales of earlier picnics along the L.A. River with Charlie Chaplin and Paulette Goddard, Greta Garbo, Bertrand Russell, and the Huxleys. The two Kenneths, Rexroth and Patchen, perform readings in your living room regularly. But poetry bores you blind, so you talk Lucy Herrmann, wife of movie composer Bernard—Bennie to you—into telling you stories upstairs. Arnold Schoenberg just laughs when you and your sister, Mirandi, get stuck together with bubble gum in the middle of the premiere of his latest piece at the Ojai Music Festival.Now imagine this:

You’re a sophomore at Hollywood High. It’s that dead time between classes and you’re in the girls’ room, smoking one of the 87 cigarettes you share daily with Sally. Sally, who before she even transferred to Hollywood High had been through the wringer at Twentieth Century Fox, signed to a contract and then summarily dropped because she’d bleached her hair an eyeball-scorching shade of platinum the night before she was supposed to report for her first day of work, rendering herself superfluous because, unbeknownst to her, the studio had been planning to make her the next natural-type beauty in the Jean Seberg mold. Sally, who finds mornings so onerous she has to chase 15 milligrams of Dexamyl with four cups of thin coffee just to drag herself to first period. Sally, who is rich and surly and sex-savvy and has recently been taken up by a group of twenty-somethings from her acting class, the Thunderbird Girls you call them, if only in your head, knockouts all, cruising around town in—what else?—Thunderbird convertibles, spending their nights on the Sunset Strip, their weekends in Palm Springs with the ring-a-ding likes of Frank Sinatra. Sally, who is your best friend.

The company you keep is fast, which is O.K. by you since fast, as it so happens, is just your speed. No woof-woof among sex kittens you. Not with your perfect skin and teeth, hair the color of vanilla ice cream, secondary sexual characteristics that are second to none. The year before, when you were 14, you went to a party you weren’t supposed to go to. A right kind of wrong guy—an Adult Male, a big beef dreamboat galoot, just what you’d had in mind when you sneaked out of the house—told you he’d give you a ride home. You jumped at the offer. But when you lost your nerve, confessed your age, he pulled the car over to the side of the road. “Don’t let guys pick you up like this, kid—you might get hurt,” he said, undercutting this gruff bit of fatherly advice by laying a five-alarm kiss on you. He drove off without telling you his name. A few months passed and there was your white knight in black-and-white, on the front page of every paper in town. He’d had a run-in with another under-age girl, only this encounter had ended in penetration: her knife in his gut. Johnny Stompanato, henchman of Mob boss Mickey Cohen, dead at the hands of the 14-year-old daughter of his squeeze, Lana Turner. Tough luck for Johnny, but a good sign for you: you caught the eye of the guy who took off the Sweater Girl’s sweater nightly. If that doesn’t make you a movie star yourself it puts you in the same firmament as one, doesn’t it? At the very least it makes you seriously hot stuff.

And you’ve got more than looks going for you. You’ve got brains too. You read all the time—Proust, Woolf, Colette, Anthony Powell. And you’re good at school, even if you spend most of your class time doodling Frederick’s of Hollywood models on the back of your notebook. You certainly have no intention of making a right turn on Sunset after graduation, moving up the road to U.C.L.A., in squarer-than-square Westwood.

by Lili Anolik, Vanity Fair | Read more:

Image: Julian Wasser

Wednesday, February 26, 2014

Here's The Best Advice From A Single Guy Who Spent A Year Interviewing Couples

Nate Bagley says he was sick of hearing love stories that fell into one of two categories — scandal and divorce, and unrealistic fairytale.

So he started a Kickstarter and used his life savings to tour the country and interview couples in happy, long-term relationships. (...)

“I’ve interviewed gay couples, straight couples, rich couples, poor couples, religious couples, atheist couples, couples who have been together for a short time, and couples who have been together for over 70 years,” he said in his Ask Me Anything. “I’ve even interviewed couples in arranged marriages and polygamous couples.”

So he started a Kickstarter and used his life savings to tour the country and interview couples in happy, long-term relationships. (...)

“I’ve interviewed gay couples, straight couples, rich couples, poor couples, religious couples, atheist couples, couples who have been together for a short time, and couples who have been together for over 70 years,” he said in his Ask Me Anything. “I’ve even interviewed couples in arranged marriages and polygamous couples.”

On the key things that make a relationship successful:

“This was actually one of the most surprising things I learned on the journey.

Self Love: The happiest couples always consisted of two (sometimes more) emotionally healthy and independently happy individuals. These people practiced self-love. They treated themselves with the same type of care that they treated their partner… or at least they tried to.

Emotionally healthy people know how to forgive, they are able to acknowledge their part in any disagreement or conflict and take responsibility for it. They are self-aware enough to be assertive, to pull their weight, and to give love when it’s most difficult.

Commitment: After that emotional health came an unquestioning level of commitment. The happiest couples knew that if shit got real, their significant other wasn’t going to walk out on them. They knew that even if things got hard – no, especially if things got hard — they were better off together. The sum of the parts is greater than the whole.

Trust: Happy couples trust each other… and they have earned each others’ trust. They don’t worry about the other person trying to undermine them or sabotage them, because they’ve proven over and over again that they are each other’s biggest advocate. That trust is built through actions, not words. It’s day after day after day of fidelity, service, emotional security, reliability.

“This was actually one of the most surprising things I learned on the journey.

Self Love: The happiest couples always consisted of two (sometimes more) emotionally healthy and independently happy individuals. These people practiced self-love. They treated themselves with the same type of care that they treated their partner… or at least they tried to.

Emotionally healthy people know how to forgive, they are able to acknowledge their part in any disagreement or conflict and take responsibility for it. They are self-aware enough to be assertive, to pull their weight, and to give love when it’s most difficult.

Commitment: After that emotional health came an unquestioning level of commitment. The happiest couples knew that if shit got real, their significant other wasn’t going to walk out on them. They knew that even if things got hard – no, especially if things got hard — they were better off together. The sum of the parts is greater than the whole.

Trust: Happy couples trust each other… and they have earned each others’ trust. They don’t worry about the other person trying to undermine them or sabotage them, because they’ve proven over and over again that they are each other’s biggest advocate. That trust is built through actions, not words. It’s day after day after day of fidelity, service, emotional security, reliability.

by Megan Willett, Business Insider | Read more:

Image: uncredited

The Internet is Fucked (but we can fix it)

Here’s a simple truth: the internet has radically changed the world. Over the course of the past 20 years, the idea of networking all the world’s computers has gone from a research science pipe dream to a necessary condition of economic and social development, from government and university labs to kitchen tables and city streets. We are all travelers now, desperate souls searching for a signal to connect us all. It is awesome.

And we’re fucking everything up.

And we’re fucking everything up.

Massive companies like AT&T and Comcast have spent the first two months of 2014 boldly announcing plans to close and control the internet through additional fees, pay-to-play schemes, and sheer brutal size — all while the legal rules designed to protect against these kinds of abuses were struck down in court for basically making too much sense. “Broadband providers represent a threat to internet openness,” concluded Judge David Tatel in Verizon’s case against the FCC’s Open Internet order, adding that the FCC had provided ample evidence of internet companies abusing their market power and had made “a rational connection between the facts found and the choices made.” Verizon argued strenuously, but had offered the court “no persuasive reason to question that judgement.”

Then Tatel cut the FCC off at the knees for making “a rather half-hearted argument” in support of its authority to properly police these threats and vacated the rules protecting the open internet, surprising observers on both sides of the industry and sending new FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler into a tailspin of empty promises seemingly designed to disappoint everyone.

“I expected the anti-blocking rule to be upheld,” National Cable and Telecommunications Association president and CEO Michael Powell told me after the ruling was issued. Powell was chairman of the FCC under George W. Bush; he issued the first no-blocking rules. “Judge Tatel basically said the Commission didn’t argue it properly.”

In the meantime, the companies that control the internet have continued down a dark path, free of any oversight or meaningful competition to check their behavior. In January, AT&T announced a new “sponsored data” plan that would dramatically alter the fierce one-click-away competition that’s thus far characterized the internet. Earlier this month, Comcast announced plans to merge with Time Warner Cable, creating an internet service behemoth that will serve 40 percent of Americans in 19 of the 20 biggest markets with virtually no rivals. (...)

In a perfect storm of corporate greed and broken government, the internet has gone from vibrant center of the new economy to burgeoning tool of economic control. Where America once had Rockefeller and Carnegie, it now has Comcast’s Brian Roberts, AT&T’s Randall Stephenson, and Verizon’s Lowell McAdam, robber barons for a new age of infrastructure monopoly built on fiber optics and kitty GIFs.

And the power of the new network-industrial complex is immense and unchecked, even by other giants: AT&T blocked Apple’s FaceTime and Google’s Hangouts video chat services for the preposterously silly reason that the apps were "preloaded" on each company’s phones instead of downloaded from an app store. Verizon and AT&T have each blocked the Google Wallet mobile payment system because they’re partners in the competing (and not very good) ISIS service. Comcast customers who stream video on their Xboxes using Microsoft’s services get charged against their data caps, but the Comcast service is tax-free.

We’re really, really fucking this up.

But we can fix it, I swear. We just have to start telling each other the truth. Not the doublespeak bullshit of regulators and lobbyists, but the actual truth. Once we have the truth, we have the power — the power to demand better not only from our government, but from the companies that serve us as well. "This is a political fight," says Craig Aaron, president of the advocacy group Free Press. "When the internet speaks with a unified voice politicians rip their hair out."

We can do it. Let’s start.

The internet is a utilility, just like water and electicity

Go ahead, say it out loud. The internet is a utility.

There, you’ve just skipped past a quarter century of regulatory corruption and lawsuits that still rage to this day and arrived directly at the obvious conclusion. Internet access isn’t a luxury or a choice if you live and participate in the modern economy, it’s a requirement.

And we’re fucking everything up.

And we’re fucking everything up.Massive companies like AT&T and Comcast have spent the first two months of 2014 boldly announcing plans to close and control the internet through additional fees, pay-to-play schemes, and sheer brutal size — all while the legal rules designed to protect against these kinds of abuses were struck down in court for basically making too much sense. “Broadband providers represent a threat to internet openness,” concluded Judge David Tatel in Verizon’s case against the FCC’s Open Internet order, adding that the FCC had provided ample evidence of internet companies abusing their market power and had made “a rational connection between the facts found and the choices made.” Verizon argued strenuously, but had offered the court “no persuasive reason to question that judgement.”

Then Tatel cut the FCC off at the knees for making “a rather half-hearted argument” in support of its authority to properly police these threats and vacated the rules protecting the open internet, surprising observers on both sides of the industry and sending new FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler into a tailspin of empty promises seemingly designed to disappoint everyone.

“I expected the anti-blocking rule to be upheld,” National Cable and Telecommunications Association president and CEO Michael Powell told me after the ruling was issued. Powell was chairman of the FCC under George W. Bush; he issued the first no-blocking rules. “Judge Tatel basically said the Commission didn’t argue it properly.”

In the meantime, the companies that control the internet have continued down a dark path, free of any oversight or meaningful competition to check their behavior. In January, AT&T announced a new “sponsored data” plan that would dramatically alter the fierce one-click-away competition that’s thus far characterized the internet. Earlier this month, Comcast announced plans to merge with Time Warner Cable, creating an internet service behemoth that will serve 40 percent of Americans in 19 of the 20 biggest markets with virtually no rivals. (...)

In a perfect storm of corporate greed and broken government, the internet has gone from vibrant center of the new economy to burgeoning tool of economic control. Where America once had Rockefeller and Carnegie, it now has Comcast’s Brian Roberts, AT&T’s Randall Stephenson, and Verizon’s Lowell McAdam, robber barons for a new age of infrastructure monopoly built on fiber optics and kitty GIFs.

And the power of the new network-industrial complex is immense and unchecked, even by other giants: AT&T blocked Apple’s FaceTime and Google’s Hangouts video chat services for the preposterously silly reason that the apps were "preloaded" on each company’s phones instead of downloaded from an app store. Verizon and AT&T have each blocked the Google Wallet mobile payment system because they’re partners in the competing (and not very good) ISIS service. Comcast customers who stream video on their Xboxes using Microsoft’s services get charged against their data caps, but the Comcast service is tax-free.

We’re really, really fucking this up.

But we can fix it, I swear. We just have to start telling each other the truth. Not the doublespeak bullshit of regulators and lobbyists, but the actual truth. Once we have the truth, we have the power — the power to demand better not only from our government, but from the companies that serve us as well. "This is a political fight," says Craig Aaron, president of the advocacy group Free Press. "When the internet speaks with a unified voice politicians rip their hair out."

We can do it. Let’s start.

The internet is a utilility, just like water and electicity

Go ahead, say it out loud. The internet is a utility.

There, you’ve just skipped past a quarter century of regulatory corruption and lawsuits that still rage to this day and arrived directly at the obvious conclusion. Internet access isn’t a luxury or a choice if you live and participate in the modern economy, it’s a requirement.

by Nilay Patel, Verge | Read more:

Image:

Tuesday, February 25, 2014

Gil Scott-Heron

[ed. Still can't believe he's gone.]

A History of Everything, Including You

Life evolved or was created. Cells trembled, and divided, and gasped and found dry land. Soon they grew legs, and fins, and hands, and antenna, and mouths, and ears, and wings, and eyes. Eyes that opened wide to take all of it in, the creeping, growing, soaring, swimming, crawling, stampeding universe.

Eyes opened and closed and opened again, we called it blinking. Above us shown a star that we called the sun. And we called the ground the earth. So we named everything including ourselves. We were man and woman and when we got lonely we figured out a way to make more of us. We called it sex, and most people enjoyed it. We fell in love. We talked about god and banged stones together, made sparks and called them fire, we got warmer and the food got better.

We got married, we had some children, they cried, and crawled, and grew. One dissected flowers, sometimes eating the petals. Another liked to chase squirrels. We fought wars over money, and honor, and women. We starved ourselves, we hired prostitutes, we purified our water. We compromised, decorated, and became esoteric. One of us stopped breathing and turned blue. Then others. First we covered them with leaves and then we buried them in the ground. We remembered them. We forgot them. We aged.

Our buildings kept getting taller. We hired lawyers and formed councils and left paper trails, we negotiated, we admitted, we got sick, and searched for cures. We invented lipstick, vaccines, pilates, solar panels, interventions, table manners, firearms, window treatments, therapy, birth control, tailgating, status symbols, palimony, sportsmanship, focus groups, zoloft, sunscreen, landscaping, cessnas, fortune cookies, chemotherapy, convenience foods, and computers. We angered militants, and our mothers.

You were born. You learned to walk, and went to school, and played sports, and lost your virginity, and got into a decent college, and majored in psychology, and went to rock shows, and became political, and got drunk, and changed your major to marketing, and wore turtleneck sweaters, and read novels, and volunteered, and went to movies, and developed a taste for blue cheese dressing.

I met you through friends, and didn’t like you at first. The feeling was mutual, but we got used to each other. We had sex for the first time behind an art gallery, standing up and slightly drunk. You held my face in your hands and said that I was beautiful. And you were too. Tall with a streetlight behind you. We went back to your place and listened to the White Album. We ordered in. We fought and made up and got good jobs and got married and bought an apartment and worked out and ate more and talked less. I got depressed. You ignored me. I was sick of you. You drank too much and got careless with money. I slept with my boss. We went into counseling and got a dog. I bought a book of sex positions and we tried the least degrading one, the wheelbarrow. You took flight lessons and subscribed to Rolling Stone. I learned Spanish and started gardening.

We had some children who more or less disappointed us but it might have been our fault. You were too indulgent and I was too critical. We loved them anyway. One of them died before we did, stabbed on the subway. We grieved. We moved. We adopted a cat. The world seemed uncertain, we lived beyond our means. I got judgmental and belligerent, you got confused and easily tired. You ignored me, I was sick of you. We forgave. We remembered. We made cocktails. We got tender. There was that time on the porch when you said, can you believe it?

This was near the end and your hands were trembling. I think you were talking about everything, including us. Did you want me to say it? So it would not be lost? It was too much for me to think about. I could not go back to the beginning. I said, not really. And we watched the sun go down. A dog kept barking in the distance, and you were tired but you smiled and you said, hear that? It’s rough, rough. And we laughed. You were like that.

Now, your question is my project and our house is full of clues. I’m reading old letters and turning over rocks. I burry my face in your sweaters. I study a photograph taken at the beach, the sun in our eyes, and the water behind us. It’s a victory to remember the forgotten picnic basket and your striped beach blanket. It’s a victory to remember how the jellyfish stung you and you ran screaming from the water. It’s a victory to remember treating the wound with meat tenderizer, and you saying, I made it better. I will tell you this, standing on our hill this morning I looked at the land we chose for ourselves, I saw a few green patches, and our sweet little shed, that same dog was barking, a storm was moving in. I did not think of heaven, but I saw that the clouds were beautiful and I watched them cover the sun.

by Jenny Hollowell, YMFY | Read more:

Image: via:

Manliness Manifesto

We live in ridiculously convenient times. Think about it: Whenever you need any kind of information, about anything, day or night, no matter where you are, you can just tap your finger on your smartphone and within seconds an answer will appear, as if by magic, on the screen. Granted, this answer will be wrong because it comes from the Internet, which is infested with teenagers, lunatics and Anthony Weiner. But it's convenient.

Today everything is convenient. You cook your meals by pushing a microwave button. Your car shifts itself, and your GPS tells you where to go. If you go to a men's public restroom, you don't even have to flush the urinal! This tedious chore is a thing of the past because the urinal now has a small electronic "eye" connected to the Central Restroom Command Post, located deep underground somewhere near Omaha, Neb., where highly trained workers watch you on high-definition TV screens and make the flush decision for you. ("I say we push the button." "Wait, not yet!")

Today everything is convenient. You cook your meals by pushing a microwave button. Your car shifts itself, and your GPS tells you where to go. If you go to a men's public restroom, you don't even have to flush the urinal! This tedious chore is a thing of the past because the urinal now has a small electronic "eye" connected to the Central Restroom Command Post, located deep underground somewhere near Omaha, Neb., where highly trained workers watch you on high-definition TV screens and make the flush decision for you. ("I say we push the button." "Wait, not yet!")

And then there's travel. A century ago, it took a week to get from New York to California; today you can board a plane at La Guardia and six hours later—think about that: six hours later!—you will, as if by magic, still be sitting in the plane at La Guardia because "La Guardia" is Italian for "You will never actually take off." But during those six hours you can be highly productive by using your smartphone to get on the Internet.

So we have it pretty easy. But we have paid a price for all this convenience: We don't know how to do anything anymore. We're helpless without our technology. Have you ever been standing in line to pay a cashier when something went wrong with the electronic cash register? Suddenly your safe, comfortable, modern world crumbles and you are plunged into a terrifying nightmare postapocalyptic hell where people might have to do math USING ONLY THEIR BRAINS.

Regular American adults are no more capable of doing math than they are of photosynthesis. If you hand a cashier a $20 bill for an item costing $13.47, both you and the cashier are going to look at the cash register to see how much you get back and both of you will unquestioningly accept the cash register's decision. It may say $6.53; it may say $5.89; it may be in a generous mood and say $8.41. But whatever it says, that's how much you will get because both you and the cashier know the machine is WAY smarter than you. (...)

But it isn't my inability to do long division that really bothers me. What really bothers me is that, like many modern American men, I don't know how to do anything manly anymore. And by "manly," I do not mean "physical." A lot of us do physical things, but these are yuppie fitness things like "spinning," and "crunches," and working on our "core," and running half-marathons and then putting "13.1" stickers on our hybrid cars so everybody will know what total cardiovascular badasses we are. (...)

We American men have lost our national manhood, and I say it's time we got it back. We need to learn to do the kinds of manly things our forefathers knew how to do. To get us started, I've created a list of some basic skills that every man should have, along with instructions. You may rest assured that these instructions are correct. I got them from the Internet.

by Dave Barry, WSJ | Read more:

Today everything is convenient. You cook your meals by pushing a microwave button. Your car shifts itself, and your GPS tells you where to go. If you go to a men's public restroom, you don't even have to flush the urinal! This tedious chore is a thing of the past because the urinal now has a small electronic "eye" connected to the Central Restroom Command Post, located deep underground somewhere near Omaha, Neb., where highly trained workers watch you on high-definition TV screens and make the flush decision for you. ("I say we push the button." "Wait, not yet!")

Today everything is convenient. You cook your meals by pushing a microwave button. Your car shifts itself, and your GPS tells you where to go. If you go to a men's public restroom, you don't even have to flush the urinal! This tedious chore is a thing of the past because the urinal now has a small electronic "eye" connected to the Central Restroom Command Post, located deep underground somewhere near Omaha, Neb., where highly trained workers watch you on high-definition TV screens and make the flush decision for you. ("I say we push the button." "Wait, not yet!")And then there's travel. A century ago, it took a week to get from New York to California; today you can board a plane at La Guardia and six hours later—think about that: six hours later!—you will, as if by magic, still be sitting in the plane at La Guardia because "La Guardia" is Italian for "You will never actually take off." But during those six hours you can be highly productive by using your smartphone to get on the Internet.

So we have it pretty easy. But we have paid a price for all this convenience: We don't know how to do anything anymore. We're helpless without our technology. Have you ever been standing in line to pay a cashier when something went wrong with the electronic cash register? Suddenly your safe, comfortable, modern world crumbles and you are plunged into a terrifying nightmare postapocalyptic hell where people might have to do math USING ONLY THEIR BRAINS.

Regular American adults are no more capable of doing math than they are of photosynthesis. If you hand a cashier a $20 bill for an item costing $13.47, both you and the cashier are going to look at the cash register to see how much you get back and both of you will unquestioningly accept the cash register's decision. It may say $6.53; it may say $5.89; it may be in a generous mood and say $8.41. But whatever it says, that's how much you will get because both you and the cashier know the machine is WAY smarter than you. (...)

But it isn't my inability to do long division that really bothers me. What really bothers me is that, like many modern American men, I don't know how to do anything manly anymore. And by "manly," I do not mean "physical." A lot of us do physical things, but these are yuppie fitness things like "spinning," and "crunches," and working on our "core," and running half-marathons and then putting "13.1" stickers on our hybrid cars so everybody will know what total cardiovascular badasses we are. (...)

We American men have lost our national manhood, and I say it's time we got it back. We need to learn to do the kinds of manly things our forefathers knew how to do. To get us started, I've created a list of some basic skills that every man should have, along with instructions. You may rest assured that these instructions are correct. I got them from the Internet.

by Dave Barry, WSJ | Read more:

Image: Peter Arkle

Publishers Withdraw More Than 120 Gibberish Papers

The publishers Springer and IEEE are removing more than 120 papers from their subscription services after a French researcher discovered that the works were computer-generated nonsense.

Over the past two years, computer scientist Cyril Labbé of Joseph Fourier University in Grenoble, France, has catalogued computer-generated papers that made it into more than 30 published conference proceedings between 2008 and 2013. Sixteen appeared in publications by Springer, which is headquartered in Heidelberg, Germany, and more than 100 were published by the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE), based in New York. Both publishers, which were privately informed by Labbé, say that they are now removing the papers.

Over the past two years, computer scientist Cyril Labbé of Joseph Fourier University in Grenoble, France, has catalogued computer-generated papers that made it into more than 30 published conference proceedings between 2008 and 2013. Sixteen appeared in publications by Springer, which is headquartered in Heidelberg, Germany, and more than 100 were published by the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE), based in New York. Both publishers, which were privately informed by Labbé, say that they are now removing the papers.

Among the works were, for example, a paper published as a proceeding from the 2013 International Conference on Quality, Reliability, Risk, Maintenance, and Safety Engineering, held in Chengdu, China. (The conference website says that all manuscripts are “reviewed for merits and contents”.) The authors of the paper, entitled ‘TIC: a methodology for the construction of e-commerce’, write in the abstract that they “concentrate our efforts on disproving that spreadsheets can be made knowledge-based, empathic, and compact”. (Nature News has attempted to contact the conference organizers and named authors of the paper but received no reply; however at least some of the names belong to real people. The IEEE has now removed the paper).

How to create a nonsense paper

Labbé developed a way to automatically detect manuscripts composed by a piece of software called SCIgen, which randomly combines strings of words to produce fake computer-science papers. SCIgen was invented in 2005 by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge to prove that conferences would accept meaningless papers — and, as they put it, “to maximize amusement” (see ‘Computer conference welcomes gobbledegook paper’). A related program generates random physics manuscript titles on the satirical website arXiv vs. snarXiv. SCIgen is free to download and use, and it is unclear how many people have done so, or for what purposes. SCIgen’s output has occasionally popped up at conferences, when researchers have submitted nonsense papers and then revealed the trick.

Labbé does not know why the papers were submitted — or even if the authors were aware of them. Most of the conferences took place in China, and most of the fake papers have authors with Chinese affiliations. Labbé has emailed editors and authors named in many of the papers and related conferences but received scant replies; one editor said that he did not work as a program chair at a particular conference, even though he was named as doing so, and another author claimed his paper was submitted on purpose to test out a conference, but did not respond on follow-up. Nature has not heard anything from a few enquiries.

Over the past two years, computer scientist Cyril Labbé of Joseph Fourier University in Grenoble, France, has catalogued computer-generated papers that made it into more than 30 published conference proceedings between 2008 and 2013. Sixteen appeared in publications by Springer, which is headquartered in Heidelberg, Germany, and more than 100 were published by the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE), based in New York. Both publishers, which were privately informed by Labbé, say that they are now removing the papers.

Over the past two years, computer scientist Cyril Labbé of Joseph Fourier University in Grenoble, France, has catalogued computer-generated papers that made it into more than 30 published conference proceedings between 2008 and 2013. Sixteen appeared in publications by Springer, which is headquartered in Heidelberg, Germany, and more than 100 were published by the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE), based in New York. Both publishers, which were privately informed by Labbé, say that they are now removing the papers.Among the works were, for example, a paper published as a proceeding from the 2013 International Conference on Quality, Reliability, Risk, Maintenance, and Safety Engineering, held in Chengdu, China. (The conference website says that all manuscripts are “reviewed for merits and contents”.) The authors of the paper, entitled ‘TIC: a methodology for the construction of e-commerce’, write in the abstract that they “concentrate our efforts on disproving that spreadsheets can be made knowledge-based, empathic, and compact”. (Nature News has attempted to contact the conference organizers and named authors of the paper but received no reply; however at least some of the names belong to real people. The IEEE has now removed the paper).

How to create a nonsense paper

Labbé developed a way to automatically detect manuscripts composed by a piece of software called SCIgen, which randomly combines strings of words to produce fake computer-science papers. SCIgen was invented in 2005 by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge to prove that conferences would accept meaningless papers — and, as they put it, “to maximize amusement” (see ‘Computer conference welcomes gobbledegook paper’). A related program generates random physics manuscript titles on the satirical website arXiv vs. snarXiv. SCIgen is free to download and use, and it is unclear how many people have done so, or for what purposes. SCIgen’s output has occasionally popped up at conferences, when researchers have submitted nonsense papers and then revealed the trick.

Labbé does not know why the papers were submitted — or even if the authors were aware of them. Most of the conferences took place in China, and most of the fake papers have authors with Chinese affiliations. Labbé has emailed editors and authors named in many of the papers and related conferences but received scant replies; one editor said that he did not work as a program chair at a particular conference, even though he was named as doing so, and another author claimed his paper was submitted on purpose to test out a conference, but did not respond on follow-up. Nature has not heard anything from a few enquiries.

by Richard Van Noorden, Nature | Read more:

Image: uncredited

Covert Agents on the Internet

One of the many pressing stories that remains to be told from the Snowden archive is how western intelligence agencies are attempting to manipulate and control online discourse with extreme tactics of deception and reputation-destruction. It’s time to tell a chunk of that story, complete with the relevant documents.

Over the last several weeks, I worked with NBC News to publish a series of articles about “dirty trick” tactics used by GCHQ’s previously secret unit, JTRIG (Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group). These were based on four classified GCHQ documents presented to the NSA and the other three partners in the English-speaking “Five Eyes” alliance. Today, we at the Intercept are publishing another new JTRIG document, in full, entitled “The Art of Deception: Training for Online Covert Operations.”

Over the last several weeks, I worked with NBC News to publish a series of articles about “dirty trick” tactics used by GCHQ’s previously secret unit, JTRIG (Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group). These were based on four classified GCHQ documents presented to the NSA and the other three partners in the English-speaking “Five Eyes” alliance. Today, we at the Intercept are publishing another new JTRIG document, in full, entitled “The Art of Deception: Training for Online Covert Operations.”By publishing these stories one by one, our NBC reporting highlighted some of the key, discrete revelations: the monitoring of YouTube and Blogger, the targeting of Anonymous with the very same DDoS attacks they accuse “hacktivists” of using, the use of “honey traps” (luring people into compromising situations using sex) and destructive viruses. But, here, I want to focus and elaborate on the overarching point revealed by all of these documents: namely, that these agencies are attempting to control, infiltrate, manipulate, and warp online discourse, and in doing so, are compromising the integrity of the internet itself.

Among the core self-identified purposes of JTRIG are two tactics: (1) to inject all sorts of false material onto the internet in order to destroy the reputation of its targets; and (2) to use social sciences and other techniques to manipulate online discourse and activism to generate outcomes it considers desirable. To see how extremist these programs are, just consider the tactics they boast of using to achieve those ends: “false flag operations” (posting material to the internet and falsely attributing it to someone else), fake victim blog posts (pretending to be a victim of the individual whose reputation they want to destroy), and posting “negative information” on various forums. (...)

Critically, the “targets” for this deceit and reputation-destruction extend far beyond the customary roster of normal spycraft: hostile nations and their leaders, military agencies, and intelligence services. In fact, the discussion of many of these techniques occurs in the context of using them in lieu of “traditional law enforcement” against peoplesuspected (but not charged or convicted) of ordinary crimes or, more broadly still, “hacktivism”, meaning those who use online protest activity for political ends.(...)

by Glenn Greenwald, The Intercept | Read more:

Image: JTRIG

Monday, February 24, 2014

The Getaway Car

For a long time now, I’ve been looking forward to this year with apprehension: 2011 is when my daughter, Julia, now 18, will undertake that very American rite of passage and “go away to college” — a phrase whose operative word is “away.” We live in Seattle, and in the Pacific Northwest, “collegeland,” as my daughter calls it, is centered in New England and New York, where most of her immediate friends will be going in September.

Though I’ve lived for 21 years in the U.S., I still have an Englishman’s stunted sense of distance. I think of 300 miles as a long journey, and all through last summer and fall, I would wake at 4 a.m. to sweat over the prospect of losing my daughter — my best companion, my anchor to the United States, the person with whom I’ve had the longest, most absorbing relationship of my adult life — to some unimaginably distant burg on the East Coast. So I was as elated as she was when she heard she’d been accepted by Stanford, her first choice. Same coast, same time zone — Within driving distance was the thought I clung to.

Though I’ve lived for 21 years in the U.S., I still have an Englishman’s stunted sense of distance. I think of 300 miles as a long journey, and all through last summer and fall, I would wake at 4 a.m. to sweat over the prospect of losing my daughter — my best companion, my anchor to the United States, the person with whom I’ve had the longest, most absorbing relationship of my adult life — to some unimaginably distant burg on the East Coast. So I was as elated as she was when she heard she’d been accepted by Stanford, her first choice. Same coast, same time zone — Within driving distance was the thought I clung to.

Interstate highways dull the reality of place and distance almost as effectively as jetliners do: I loathe their scary monotony. I wanted to make palpable the mileage that will stretch between us come September and feel on my own pulse the physical geography of our separation. We would take the coast road and mark out the wriggly, thousand-mile track that leads from my workroom to her future dorm in California.

Julia and I are old hands at taking road trips on her spring breaks, and stuffing our bags into the inadequate trunk of my two-seater convertible on a damp Sunday morning in early April, I sensed that this one might turn out to be our last. In the same car, or its identical predecessor, we’d driven to the Baja peninsula, the Grand Canyon, eastern Montana, British Columbia, on minor roads and with the top down, to open us as far as possible to the world we traveled through.

The rain that morning was the fine-sifted Northwest drizzle that grays this corner of the country for weeks on end; too heavy for the windshield wipers on intermittent and too light for slow, when the wipers skreak and whine on dry glass. To quicken us on our way, I steeled myself to take the Interstate as far as Olympia, the state capital, 60 miles to the southwest, from where we’d branch out to the coast. On the freeway, tire rumble and the kerchunk-kerchunk of our hard suspension’s rattling over expansion joints made conversation impossible, and the car felt as small as a pill bug, likely to be squashed flat by the next 18-wheeler. Julia wired herself to her iPod.

She was 3, going on 4, when her mother and I separated, and she could barely remember a time when she hadn’t commuted between two Seattle houses, twice a week, under the terms of the joint-custody agreement. First she moved with her stuffed bear, then with bear plus live dog; nowadays she traveled with so much stuff that she looked like an overladen packhorse when she staggered out the door with it. College offered her the promise of a life more secure and regular than any she had known since 1996 — an end to all that house-to-school-to-the-other-house gypsying that she managed with forbearing grace. Much as I feared her going away, I knew what a luxury it would be for her to have her books, clothes and bed in one room for the length of a college quarter.

[ed.Repost: June 12, 2011]

Though I’ve lived for 21 years in the U.S., I still have an Englishman’s stunted sense of distance. I think of 300 miles as a long journey, and all through last summer and fall, I would wake at 4 a.m. to sweat over the prospect of losing my daughter — my best companion, my anchor to the United States, the person with whom I’ve had the longest, most absorbing relationship of my adult life — to some unimaginably distant burg on the East Coast. So I was as elated as she was when she heard she’d been accepted by Stanford, her first choice. Same coast, same time zone — Within driving distance was the thought I clung to.

Though I’ve lived for 21 years in the U.S., I still have an Englishman’s stunted sense of distance. I think of 300 miles as a long journey, and all through last summer and fall, I would wake at 4 a.m. to sweat over the prospect of losing my daughter — my best companion, my anchor to the United States, the person with whom I’ve had the longest, most absorbing relationship of my adult life — to some unimaginably distant burg on the East Coast. So I was as elated as she was when she heard she’d been accepted by Stanford, her first choice. Same coast, same time zone — Within driving distance was the thought I clung to.Interstate highways dull the reality of place and distance almost as effectively as jetliners do: I loathe their scary monotony. I wanted to make palpable the mileage that will stretch between us come September and feel on my own pulse the physical geography of our separation. We would take the coast road and mark out the wriggly, thousand-mile track that leads from my workroom to her future dorm in California.

Julia and I are old hands at taking road trips on her spring breaks, and stuffing our bags into the inadequate trunk of my two-seater convertible on a damp Sunday morning in early April, I sensed that this one might turn out to be our last. In the same car, or its identical predecessor, we’d driven to the Baja peninsula, the Grand Canyon, eastern Montana, British Columbia, on minor roads and with the top down, to open us as far as possible to the world we traveled through.

The rain that morning was the fine-sifted Northwest drizzle that grays this corner of the country for weeks on end; too heavy for the windshield wipers on intermittent and too light for slow, when the wipers skreak and whine on dry glass. To quicken us on our way, I steeled myself to take the Interstate as far as Olympia, the state capital, 60 miles to the southwest, from where we’d branch out to the coast. On the freeway, tire rumble and the kerchunk-kerchunk of our hard suspension’s rattling over expansion joints made conversation impossible, and the car felt as small as a pill bug, likely to be squashed flat by the next 18-wheeler. Julia wired herself to her iPod.

She was 3, going on 4, when her mother and I separated, and she could barely remember a time when she hadn’t commuted between two Seattle houses, twice a week, under the terms of the joint-custody agreement. First she moved with her stuffed bear, then with bear plus live dog; nowadays she traveled with so much stuff that she looked like an overladen packhorse when she staggered out the door with it. College offered her the promise of a life more secure and regular than any she had known since 1996 — an end to all that house-to-school-to-the-other-house gypsying that she managed with forbearing grace. Much as I feared her going away, I knew what a luxury it would be for her to have her books, clothes and bed in one room for the length of a college quarter.

by Jonathan Rabin, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Dru Donovan[ed.Repost: June 12, 2011]

Sunday, February 23, 2014

may i feel said he

may i feel said he

by e e cummings

may i feel said he

(i'll squeal said she

just once said he)

it's fun said she

(i'll squeal said she

just once said he)

it's fun said she

(may i touch said he

how much said she

a lot said he)

why not said she

how much said she

a lot said he)

why not said she

(let's go said he

not too far said she

what's too far said he

where you are said she)

not too far said she

what's too far said he

where you are said she)

may i stay said he

(which way said she

like this said he

if you kiss said she

(which way said she

like this said he

if you kiss said she

may i move said he

is it love said she)

if you're willing said he

(but you're killing said she

is it love said she)

if you're willing said he

(but you're killing said she

but it's life said he

but your wife said she

now said he)

ow said she

but your wife said she

now said he)

ow said she

(tiptop said he

don't stop said she

oh no said he)

go slow said she

don't stop said she

oh no said he)

go slow said she

(cccome?said he

ummm said she)

you're divine! said he

(you are Mine said she)

ummm said she)

you're divine! said he

(you are Mine said she)

All Made Up

As a teenager, I had acne. Not the acute kind that could be cured by Acutaine, but the milder variety that didn’t go away even with copious use of Stridex pads and Phisohex. My spotty face eroded my self-esteem and made it hard for me to look people in the eye. But something positive did come out of those painful, pimple-ridden years: I discovered makeup and my life became richer for it.

When you start to ponder it, you realize that makeup is a profound product. It plays a special and intimate role in the drive for self-improvement. Clothes cover and festoon a large expanse of the body, but makeup interacts with that smaller, more expressive part: the face. It is a unique prosthetic, having practically no volume and no density, no beginning or end with respect to what it assists. It melts into the flesh, it intermingles with the self.

When you start to ponder it, you realize that makeup is a profound product. It plays a special and intimate role in the drive for self-improvement. Clothes cover and festoon a large expanse of the body, but makeup interacts with that smaller, more expressive part: the face. It is a unique prosthetic, having practically no volume and no density, no beginning or end with respect to what it assists. It melts into the flesh, it intermingles with the self.Women’s application of makeup is an update of the Narcissus myth. It cannot be applied; or at least not well; without looking in a mirror. The self-reflexive gaze required has elements of the lover’s gaze: Eyes and lips are focal points and demand the most attention and care. Thus, applying makeup is a ritual of self-love, a kind of worship at the shrine of the self, though it can also reflect insecurity and even self-loathing. At its best, it is an exercise in self-critique, and, if you’ll permit me to be grandiose, a path to self-knowledge.

I suspect that people who get upset about makeup are displacing anger about something else. “I have heard of your paintings, well enough,” Hamlet rants at Ophelia. “God hath given you one face, and you make yourselves another.” We know that Hamlet was really angry at his mother for marrying his uncle, but he took it out on poor Ophelia, who probably wore little more than some blush and a little lip gloss. Or maybe the anger Hamlet expresses is really aimed beyond the parameters of the play at another queen, Shakespeare’s Elizabeth, who didn’t stint with the foundation: “Now get you to my lady’s chamber, and tell her, let her paint an inch thick, to this favor she must come.”

If the makeup of the Virgin Queen was abundant but one-note (lots and lots of pancake), that of another, decidedly not virgin queen, Cleopatra, was both copious and varied. I imagine her makeup area resembling the ground floor of Bloomingdale’s. Among her more original innovations were green malachite and goose grease for her eyes, crushed carmine beetles mixed with ant eggs for her lips, and liquid gold for her nipples. The cosmetic industry has certainly dropped the ball on this one; where is “nipple gold from Chanel?"