Bathing in the Win, Aug. 8 | We were treated to many a Gatorade bath in the Mariners’ stretch run. Every night there was a different hero. But on more than a few nights the hero was Cal Raleigh. Still, knowing that a splash bath is coming doesn’t mean it’s going to go the way you think it will. Typically the photographers in the first base well will jockey to an angle where they think the moment will happen. Often, if a player sees or senses the bucket coming, they’ll run away or turn, or possibly the bucket will just miss and hit poor broadcaster Jen Mueller. In this game against Tampa, however, Jorge Polanco took a very roundabout path to get at Raleigh — something it was apparent he’d never see coming. (Mueller, to her credit, never gave the incoming bath away; she just stood there and took it.) Raleigh absorbed the majority of the perfectly placed cooler, basking in the bath as the fans cheered. A magical moment from a magical season. — Dean Rutz / The Seattle Times

Seattle Times - Pictures of the Year 2025

Showing posts with label Cities. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Cities. Show all posts

Wednesday, February 18, 2026

‘Millionaires Tax’ Finds Seattle is Far Richer Than Anyone Knew

Seattle’s new mayor was speaking to a roomful of supporters the other day when she dropped a rather blunt assessment of our city.

“You know what?” Katie Wilson said. “This city is filthy rich.”

The crowd laughed a bit. Can you say that when you’re mayor? Should you say that?

It bears some examination, because of what was announced next.

The city’s new social housing tax, levied on lofty pay packages to pay for public housing, was due Jan. 31. The startling news was that it blew the projections out of the water.

When the 5% tax on salaries and compensation above $1 million passed a year ago, its backers estimated it would bring in $50 million annually. Later the city’s finance department used state employment data for a more rigorous finding, and came up with $65.8 million.

But it looked precarious.

“The increase to the payroll expense tax … could cause businesses to change their hiring behavior to avoid taxation — such as moving existing employees to locations outside Seattle,” a report to the City Council said.

Conclusion: There’s “a large amount of uncertainty,” said the office of economic and revenue forecasts. The tax could collect anywhere from $39.2 million to $80 million, “but even larger variance cannot be ruled out.”

“Larger variance” is once again the story of just how rich we are. Because tax collections came in at $115 million — 75% higher than the estimate. And 44% over the top of the range.

It means several things about our city — all of which inform the debates currently raging about tax-the-rich efforts in our state.

One is that Seattle’s plutocrats are wealthier than anyone imagines. This keeps getting revealed, where a scheme is developed to tax wealth, and then the amounts the tax brings in wildly overshoot even the most optimistic forecasts...

Another thing is that Seattle businesses obviously did not flee.

This is interesting because the social housing tax should be one of the easier taxes to avoid. You only have to work at least half the time outside the city — in an office across the lake in Bellevue, for example.

If you make, say, $1.1 million, the social housing tax paid by your company would be $5,000 (5% of the $100,000 above $1 million). It’s probably not worth moving an executive due to five grand.

But one making $10 million? The tax on that is $450,000. $30 million? The tax hits $1.45 million.

As I wrote last year, it’d be cheaper for Amazon to fly its top execs to Bellevue in a helicopter three days a week.

They did not take me up on this strategic advice, apparently. In fact, the 5% tax is being paid by 170 Seattle companies, according to the social housing agency. (The tax is paid by companies, not individual workers.)

So are the rich set to bolt the city or the state to get away from tax-the-rich schemes? Last week at a hearing on a proposed state “millionaires income tax,” Redmond hedge fund manager Brian Heywood, who himself fled California’s taxes, testified he knows of “about 50 couples who are already in the process of, or soon to be changing, their domicile, out of this state.”

That is a lot. I’m not sure I know 50 couples period, let alone 50 couples capable of taking such decisive action. Another way the rich are different than you or me.

The press has been filled with anecdotes of wealthy people decamping. Yet someone’s got to be hanging on here paying all these taxes — the totals of which keep racking up dramatically higher than expected.

One tech exec finally emerged to argue the fleeing-from-Seattle talk is bogus.

“The math doesn’t math,” wrote Jacob Colker, a Seattle AI venture capitalist. “Should we be thoughtful about tax policy? Heck yeah. Should it be tied to better stewardship of spending? Darn right. But the breathless narrative that Seattle is one bill from collapse is not serious analysis.”

My sense is taxes work when rates are reasonable. Single digits, like the 5% social housing tax, are not killer rates. Maybe the rich say “ugh, I don’t like it but oh well, it’s not worth uprooting my life.” So far, it hasn’t been worth even driving across the bridge.

On the other hand, Democrats last year jacked the top estate tax rate for the super-wealthy, to a gouging 35% for wealth north of $12 million. Some of those are said to be fleeing Washington, and who can blame them? There’s no good to come from fleecing people. This extreme rate situation has set off enough alarms that state Democrats now have a “tail between their legs” bill to unwind that rate back to where it was set for years, 20%.

Point is, keep it cool, lawmakers, and the rich can abide.

“What people I think are failing to recognize is that tipping-point scenario,” he said, which would lead the state to lose the entrepreneurial advantages that have led to the growth of companies like Amazon, T-Mobile and Starbucks.

“You know what?” Katie Wilson said. “This city is filthy rich.”

The crowd laughed a bit. Can you say that when you’re mayor? Should you say that?

It bears some examination, because of what was announced next.

The city’s new social housing tax, levied on lofty pay packages to pay for public housing, was due Jan. 31. The startling news was that it blew the projections out of the water.

When the 5% tax on salaries and compensation above $1 million passed a year ago, its backers estimated it would bring in $50 million annually. Later the city’s finance department used state employment data for a more rigorous finding, and came up with $65.8 million.

But it looked precarious.

“The increase to the payroll expense tax … could cause businesses to change their hiring behavior to avoid taxation — such as moving existing employees to locations outside Seattle,” a report to the City Council said.

Conclusion: There’s “a large amount of uncertainty,” said the office of economic and revenue forecasts. The tax could collect anywhere from $39.2 million to $80 million, “but even larger variance cannot be ruled out.”

“Larger variance” is once again the story of just how rich we are. Because tax collections came in at $115 million — 75% higher than the estimate. And 44% over the top of the range.

It means several things about our city — all of which inform the debates currently raging about tax-the-rich efforts in our state.

One is that Seattle’s plutocrats are wealthier than anyone imagines. This keeps getting revealed, where a scheme is developed to tax wealth, and then the amounts the tax brings in wildly overshoot even the most optimistic forecasts...

Another thing is that Seattle businesses obviously did not flee.

This is interesting because the social housing tax should be one of the easier taxes to avoid. You only have to work at least half the time outside the city — in an office across the lake in Bellevue, for example.

If you make, say, $1.1 million, the social housing tax paid by your company would be $5,000 (5% of the $100,000 above $1 million). It’s probably not worth moving an executive due to five grand.

But one making $10 million? The tax on that is $450,000. $30 million? The tax hits $1.45 million.

As I wrote last year, it’d be cheaper for Amazon to fly its top execs to Bellevue in a helicopter three days a week.

They did not take me up on this strategic advice, apparently. In fact, the 5% tax is being paid by 170 Seattle companies, according to the social housing agency. (The tax is paid by companies, not individual workers.)

So are the rich set to bolt the city or the state to get away from tax-the-rich schemes? Last week at a hearing on a proposed state “millionaires income tax,” Redmond hedge fund manager Brian Heywood, who himself fled California’s taxes, testified he knows of “about 50 couples who are already in the process of, or soon to be changing, their domicile, out of this state.”

That is a lot. I’m not sure I know 50 couples period, let alone 50 couples capable of taking such decisive action. Another way the rich are different than you or me.

The press has been filled with anecdotes of wealthy people decamping. Yet someone’s got to be hanging on here paying all these taxes — the totals of which keep racking up dramatically higher than expected.

One tech exec finally emerged to argue the fleeing-from-Seattle talk is bogus.

“The math doesn’t math,” wrote Jacob Colker, a Seattle AI venture capitalist. “Should we be thoughtful about tax policy? Heck yeah. Should it be tied to better stewardship of spending? Darn right. But the breathless narrative that Seattle is one bill from collapse is not serious analysis.”

My sense is taxes work when rates are reasonable. Single digits, like the 5% social housing tax, are not killer rates. Maybe the rich say “ugh, I don’t like it but oh well, it’s not worth uprooting my life.” So far, it hasn’t been worth even driving across the bridge.

On the other hand, Democrats last year jacked the top estate tax rate for the super-wealthy, to a gouging 35% for wealth north of $12 million. Some of those are said to be fleeing Washington, and who can blame them? There’s no good to come from fleecing people. This extreme rate situation has set off enough alarms that state Democrats now have a “tail between their legs” bill to unwind that rate back to where it was set for years, 20%.

Point is, keep it cool, lawmakers, and the rich can abide.

by Danny Westneat, Seattle Times | Read more:

Image: Dean Rutz

[ed. I'm all for taxing the super rich, but c'mon, get serious liberals. The solution to every problem is not taxing everyone and everything in sight (or immediately jumping to extremes on public issues, like 'Defund the Police' - one of the dumbest initiatives imaginable). Washington is one of the taxingest states in country, mitigated only by the fact that there's no state income tax (although there's continual chattering about 'fixing' that), with some of the most regressive sales taxes in the country as well. Fortunately, some people seem to be coming to their senses - see also: WA Democrats consider retreat on estate tax, fearing wealth exodus (ST):]

Democrats in the state Legislature have generally dismissed warnings that new taxes on the very wealthy might lead multimillionaires to flee to lower-tax states.

But some are now acknowledging that one tax-the-rich policy they approved last year — a big increase in Washington’s top estate tax rates — may have backfired...

The problem for Washington isn’t just a single shift like the estate tax, Carlyle said, but an “aggregation of taxes” adopted swiftly in recent years, including new business and payroll taxes.

Democrats in the state Legislature have generally dismissed warnings that new taxes on the very wealthy might lead multimillionaires to flee to lower-tax states.

But some are now acknowledging that one tax-the-rich policy they approved last year — a big increase in Washington’s top estate tax rates — may have backfired...

The problem for Washington isn’t just a single shift like the estate tax, Carlyle said, but an “aggregation of taxes” adopted swiftly in recent years, including new business and payroll taxes.

“What people I think are failing to recognize is that tipping-point scenario,” he said, which would lead the state to lose the entrepreneurial advantages that have led to the growth of companies like Amazon, T-Mobile and Starbucks.

Labels:

Business,

Cities,

Economics,

Government,

Politics

Monday, February 16, 2026

Life at the Frontlines of Demographic Collapse

Nagoro, a depopulated village in Japan where residents are replaced by dolls.

In 1960, Yubari, a former coal-mining city on Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido, had roughly 110,000 residents. Today, fewer than 7,000 remain. The share of those over 65 is 54%. The local train stopped running in 2019. Seven elementary schools and four junior high schools have been consolidated into just two buildings. Public swimming pools have closed. Parks are not maintained. Even the public toilets at the train station were shut down to save money.

Much has been written about the economic consequences of aging and shrinking populations. Fewer workers supporting more retirees will make pension systems buckle. Living standards will decline. Healthcare will get harder to provide. But that’s dry theory. A numbers game. It doesn’t tell you what life actually looks like at ground zero.

Germany took a similar approach with its Stadtumbau Ost, a federal program launched after reunification to address the exodus from East to West, as young people moved west for work, leaving behind more than a million vacant apartments. It paid to demolish nearly 300,000 housing units. The idea was not to lure people back but to stabilize what was left: reduce the housing surplus, concentrate investment in viable neighborhoods, and stop the downward spiral of vacancy breeding more vacancy. It was not a happy solution, but it was a workable one.

Yet this approach is politically toxic. Try campaigning not on an optimistic message of turning the tide and making the future as bright as it once used to be, but rather by telling voters that their neighborhood is going to be abandoned, that the bus won’t run anymore and that all the investment is going to go to a different district. Try telling the few remaining inhabitants of a valley that you can’t justify spending money on their flood defenses. [...]

*** So what is being done about these problems?

Take the case of infrastructure and services degradation. The solution is obvious: manage the decline by concentrating the population.

In 2014, the Japanese government initiated Location Normalization Plans to designate areas for concentrating hospitals, government offices, and commerce in walkable downtown cores. Tax incentives and housing subsidies were offered to attract residents. By 2020, dozens of Tokyo-area municipalities had adopted these plans.

Cities like Toyama built light rail transit and tried to concentrate development along the line, offering housing subsidies within 500 meters of stations. The results are modest: between 2005 and 2013, the percentage of Toyama residents living in the city center increased from 28% to 32%. Meanwhile, the city’s overall population continued to decline, and suburban sprawl persisted beyond the plan’s reach.

What about the water pipes? In theory, they can be decommissioned and consolidated, when people move out of some neighborhoods. At places, they can possibly be replaced with smaller-diameter pipes. Engineers can even open hydrants periodically to keep water flowing. But the most efficient of these measures were probably easier to implement in the recently post-totalitarian East Germany, with its still-docile population accustomed to state directives, than in democratic Japan.

In 1960, Yubari, a former coal-mining city on Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido, had roughly 110,000 residents. Today, fewer than 7,000 remain. The share of those over 65 is 54%. The local train stopped running in 2019. Seven elementary schools and four junior high schools have been consolidated into just two buildings. Public swimming pools have closed. Parks are not maintained. Even the public toilets at the train station were shut down to save money.

Much has been written about the economic consequences of aging and shrinking populations. Fewer workers supporting more retirees will make pension systems buckle. Living standards will decline. Healthcare will get harder to provide. But that’s dry theory. A numbers game. It doesn’t tell you what life actually looks like at ground zero.

And it’s not all straightforward. Consider water pipes. Abandoned houses are photogenic. It’s the first image that comes to mind when you picture a shrinking city. But as the population declines, ever fewer people live in the same housing stock and water consumption declines. The water sits in oversized pipes. It stagnates and chlorine dissipates. Bacteria move in, creating health risks. You can tear down an abandoned house in a week. But you cannot easily downsize a city’s pipe network. The infrastructure is buried under streets and buildings. The cost of ripping it out and replacing it with smaller pipes would bankrupt a city that is already bleeding residents and tax revenue. As the population shrinks, problems like this become ubiquitous.

The common instinct is to fight decline with growth. Launch a tourism campaign. Build a theme park or a tech incubator. Offer subsidies and tax breaks to young families willing to move in. Subsidize childcare. Sell houses for €1, as some Italian towns do.

Well, Yubari tried this. After the coal mines closed, the city pivoted to tourism, opening a coal-themed amusement park, a fossil museum, and a ski resort. They organized a film festival. Celebrities came and left. None of it worked. By 2007 the city went bankrupt. The festival was canceled and the winners from years past never got their prize money.

Or, to get a different perspective, consider someone who moved to a shrinking Italian town, lured by a €1 house offer: They are about to retire. They want to live in the country. So they buy the house, go through all the paperwork. Then they renovate it. More paperwork. They don't speak Italian. That sucks. But finally everything works out. They move in. The house is nice. There's grapevine climbing the front wall. Out of the window they see the rolling hills of Sicily. In the evenings, they hears dogs barking in the distance. It looks exactly like the paradise they'd imagined. But then they start noticing their elderly neighbors getting sick and being taken away to hospital, never to return. They see them dying alone in their half-abandoned houses. And as the night closes in, they can't escape the thought: "When's my turn?" Maybe they shouldn't have come at all.

The instinctive approach, that vain attempt to grow and repopulate, is often counterproductive. It leads to building infrastructure, literal bridges to nowhere, waiting for people that will never come. Subsidies quietly fizzle out, leaving behind nothing but dilapidated billboards advertising the amazing attractions of the town, attractions that closed their gates a decade ago.

The alternative is not to fight the decline, but to manage it. To accept that the population is not coming back and ask a different question: how do you make a smaller city livable for those who remain? In Yubari, the current mayor has stopped talking about attracting new residents. The new goal is consolidation. Relocating the remaining population closer to the city center, where services can be still delivered, where the pipes are still the right size, where neighbors are close enough to check on each other.

The common instinct is to fight decline with growth. Launch a tourism campaign. Build a theme park or a tech incubator. Offer subsidies and tax breaks to young families willing to move in. Subsidize childcare. Sell houses for €1, as some Italian towns do.

Well, Yubari tried this. After the coal mines closed, the city pivoted to tourism, opening a coal-themed amusement park, a fossil museum, and a ski resort. They organized a film festival. Celebrities came and left. None of it worked. By 2007 the city went bankrupt. The festival was canceled and the winners from years past never got their prize money.

Or, to get a different perspective, consider someone who moved to a shrinking Italian town, lured by a €1 house offer: They are about to retire. They want to live in the country. So they buy the house, go through all the paperwork. Then they renovate it. More paperwork. They don't speak Italian. That sucks. But finally everything works out. They move in. The house is nice. There's grapevine climbing the front wall. Out of the window they see the rolling hills of Sicily. In the evenings, they hears dogs barking in the distance. It looks exactly like the paradise they'd imagined. But then they start noticing their elderly neighbors getting sick and being taken away to hospital, never to return. They see them dying alone in their half-abandoned houses. And as the night closes in, they can't escape the thought: "When's my turn?" Maybe they shouldn't have come at all.

***

The alternative is not to fight the decline, but to manage it. To accept that the population is not coming back and ask a different question: how do you make a smaller city livable for those who remain? In Yubari, the current mayor has stopped talking about attracting new residents. The new goal is consolidation. Relocating the remaining population closer to the city center, where services can be still delivered, where the pipes are still the right size, where neighbors are close enough to check on each other.

Germany took a similar approach with its Stadtumbau Ost, a federal program launched after reunification to address the exodus from East to West, as young people moved west for work, leaving behind more than a million vacant apartments. It paid to demolish nearly 300,000 housing units. The idea was not to lure people back but to stabilize what was left: reduce the housing surplus, concentrate investment in viable neighborhoods, and stop the downward spiral of vacancy breeding more vacancy. It was not a happy solution, but it was a workable one.

Yet this approach is politically toxic. Try campaigning not on an optimistic message of turning the tide and making the future as bright as it once used to be, but rather by telling voters that their neighborhood is going to be abandoned, that the bus won’t run anymore and that all the investment is going to go to a different district. Try telling the few remaining inhabitants of a valley that you can’t justify spending money on their flood defenses. [...]

*** So what is being done about these problems?

Take the case of infrastructure and services degradation. The solution is obvious: manage the decline by concentrating the population.

In 2014, the Japanese government initiated Location Normalization Plans to designate areas for concentrating hospitals, government offices, and commerce in walkable downtown cores. Tax incentives and housing subsidies were offered to attract residents. By 2020, dozens of Tokyo-area municipalities had adopted these plans.

Cities like Toyama built light rail transit and tried to concentrate development along the line, offering housing subsidies within 500 meters of stations. The results are modest: between 2005 and 2013, the percentage of Toyama residents living in the city center increased from 28% to 32%. Meanwhile, the city’s overall population continued to decline, and suburban sprawl persisted beyond the plan’s reach.

What about the water pipes? In theory, they can be decommissioned and consolidated, when people move out of some neighborhoods. At places, they can possibly be replaced with smaller-diameter pipes. Engineers can even open hydrants periodically to keep water flowing. But the most efficient of these measures were probably easier to implement in the recently post-totalitarian East Germany, with its still-docile population accustomed to state directives, than in democratic Japan.

***

And then there’s the problem of abandoned houses.

The arithmetic is brutal: you inherit a rural house valued at ¥5 million on the cadastral registry and pay inheritance tax of 55%, only to discover that the actual market value is ¥0. Nobody wants property in a village hemorrhaging population. But wait! If the municipality formally designates it a “vacant house,” your property tax increases sixfold. Now you face half a million yen in fines for non-compliance, and administrative demolition costs that average ¥2 million. You are now over ¥5 million in debt for a property you never wanted and cannot sell.

It gets more bizarre: When you renounce the inheritance, it passes to the next tier of relatives. If children renounce, it goes to parents. If parents renounce, it goes to siblings. If siblings renounce, it goes to nieces and nephews. By renouncing a property, you create an unpleasant surprise for your relatives.

Finally, when every possible relative renounces, the family court appoints an administrator to manage the estate. Their task is to search for other potential heirs, such as "persons with special connection," i.e. those who cared for the deceased, worked closely with them and so on. Lucky them, the friends and colleagues!

Obviously, this gets tricky and that’s exactly the reason why a new system was introduced to allows a property to be passed to the state. But there are many limitations placed on the property — essentially, the state will only accept land that has some value.

In the end, it's a hot potato problem. The legal system was designed in the era when all property had value and implicitly assumed that people wanted it. Now that many properties have negative value, the framework misfires, creates misaligned incentives and recent fixes all too often make the problem worse.

The arithmetic is brutal: you inherit a rural house valued at ¥5 million on the cadastral registry and pay inheritance tax of 55%, only to discover that the actual market value is ¥0. Nobody wants property in a village hemorrhaging population. But wait! If the municipality formally designates it a “vacant house,” your property tax increases sixfold. Now you face half a million yen in fines for non-compliance, and administrative demolition costs that average ¥2 million. You are now over ¥5 million in debt for a property you never wanted and cannot sell.

It gets more bizarre: When you renounce the inheritance, it passes to the next tier of relatives. If children renounce, it goes to parents. If parents renounce, it goes to siblings. If siblings renounce, it goes to nieces and nephews. By renouncing a property, you create an unpleasant surprise for your relatives.

Finally, when every possible relative renounces, the family court appoints an administrator to manage the estate. Their task is to search for other potential heirs, such as "persons with special connection," i.e. those who cared for the deceased, worked closely with them and so on. Lucky them, the friends and colleagues!

Obviously, this gets tricky and that’s exactly the reason why a new system was introduced to allows a property to be passed to the state. But there are many limitations placed on the property — essentially, the state will only accept land that has some value.

In the end, it's a hot potato problem. The legal system was designed in the era when all property had value and implicitly assumed that people wanted it. Now that many properties have negative value, the framework misfires, creates misaligned incentives and recent fixes all too often make the problem worse.

by Martin Sustrik, Less Wrong | Read more:

Image:Vimeo/uncredited

Image:Vimeo/uncredited

Friday, February 13, 2026

Something Surprising Happens When Bus Rides Are Free

Free buses? Really? Of all the promises that Zohran Mamdani made during his New York City mayoral campaign, that one struck some skeptics as the most frivolous leftist fantasy. Unlike housing, groceries and child care, which weigh heavily on New Yorkers’ finances, a bus ride is just a few bucks. Is it really worth the huge effort to spare people that tiny outlay?

As a lawyer, I feel most strongly about the least-discussed benefit: Eliminating bus fares can clear junk cases out of our court system, lowering the crushing caseloads that prevent our judges, prosecutors and public defenders from focusing their attention where it’s most needed.

It is. Far beyond just saving riders money, free buses deliver a cascade of benefits, from easing traffic to promoting public safety. Just look at Boston; Chapel Hill, N.C.; Richmond, Va.; Kansas City, Mo.; and even New York itself, all of which have tried it to excellent effect. And it doesn’t have to be costly — in fact, it can come out just about even.

As a lawyer, I feel most strongly about the least-discussed benefit: Eliminating bus fares can clear junk cases out of our court system, lowering the crushing caseloads that prevent our judges, prosecutors and public defenders from focusing their attention where it’s most needed.

I was a public defender, and in one of my first cases I was asked to represent a woman who was not a robber or a drug dealer — she was someone who had failed to pay the fare on public transit. Precious resources had been spent arresting, processing, prosecuting and trying her, all for the loss of a few dollars. This is a daily feature of how we criminalize poverty in America.

Unless a person has spent real time in the bowels of a courthouse, it’s hard to imagine how many of the matters clogging criminal courts across the country originate from a lack of transit. Some of those cases result in fines; many result in defendants being ordered to attend community service or further court dates. But if the person can’t afford the fare to get to those appointments and can’t get a ride, their only options — jump a turnstile or flout a judge’s order — expose them to re-arrest. Then they may face jail time, which adds significant pressure to our already overcrowded facilities. Is this really what we want the courts spending time on?

Free buses can unclog our streets, too. In Boston, eliminating the need for riders to pay fares or punch tickets cut boarding time by as much as 23 percent, which made everyone’s trip faster. Better, cheaper, faster bus rides give automobile owners an incentive to leave their cars at home, which makes the journey faster still — for those onboard as well as those who still prefer to drive.

How much should a government be willing to pay to achieve those outcomes? How about nothing? When Washington State’s public transit systems stopped charging riders, in many municipalities the state came out more or less even — because the money lost on fares was balanced out by the enormous savings that ensued.

Fare evasion was one of the factors that prompted Mayor Eric Adams to flood New York City public transit with police officers. New Yorkers went from shelling out $4 million for overtime in 2022 to $155 million in 2024. What did it get them? In September 2024, officers drew their guns to shoot a fare beater — pause for a moment to think about that — and two innocent bystanders ended up with bullet wounds, the kind of accident that’s all but inevitable in such a crowded setting.

New York City tried a free bus pilot program in 2023 and 2024 and, as predicted, ridership increased — by 30 percent on weekdays and 38 percent on weekends, striking figures that could make a meaningful dent in New York’s chronic traffic problem (and, by extension, air and noise pollution). Something else happened that was surprising: Assaults on bus operators dropped 39 percent. Call it the opposite of the Adams strategy: Lowering barriers to access made for fewer tense law enforcement encounters, fewer acts of desperation and a safer city overall.

by Emily Galvin Almanza, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Brian Blomerth

Unless a person has spent real time in the bowels of a courthouse, it’s hard to imagine how many of the matters clogging criminal courts across the country originate from a lack of transit. Some of those cases result in fines; many result in defendants being ordered to attend community service or further court dates. But if the person can’t afford the fare to get to those appointments and can’t get a ride, their only options — jump a turnstile or flout a judge’s order — expose them to re-arrest. Then they may face jail time, which adds significant pressure to our already overcrowded facilities. Is this really what we want the courts spending time on?

Free buses can unclog our streets, too. In Boston, eliminating the need for riders to pay fares or punch tickets cut boarding time by as much as 23 percent, which made everyone’s trip faster. Better, cheaper, faster bus rides give automobile owners an incentive to leave their cars at home, which makes the journey faster still — for those onboard as well as those who still prefer to drive.

How much should a government be willing to pay to achieve those outcomes? How about nothing? When Washington State’s public transit systems stopped charging riders, in many municipalities the state came out more or less even — because the money lost on fares was balanced out by the enormous savings that ensued.

Fare evasion was one of the factors that prompted Mayor Eric Adams to flood New York City public transit with police officers. New Yorkers went from shelling out $4 million for overtime in 2022 to $155 million in 2024. What did it get them? In September 2024, officers drew their guns to shoot a fare beater — pause for a moment to think about that — and two innocent bystanders ended up with bullet wounds, the kind of accident that’s all but inevitable in such a crowded setting.

New York City tried a free bus pilot program in 2023 and 2024 and, as predicted, ridership increased — by 30 percent on weekdays and 38 percent on weekends, striking figures that could make a meaningful dent in New York’s chronic traffic problem (and, by extension, air and noise pollution). Something else happened that was surprising: Assaults on bus operators dropped 39 percent. Call it the opposite of the Adams strategy: Lowering barriers to access made for fewer tense law enforcement encounters, fewer acts of desperation and a safer city overall.

by Emily Galvin Almanza, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Brian Blomerth

Labels:

Business,

Cities,

Crime,

Economics,

Government,

Politics,

Technology,

Travel

Wednesday, February 4, 2026

In Praise of Urban Disorder

In his essay “Planning for an Unplanned City,” Jason Thorne, Toronto’s chief planner, poses a pair of provocative questions to his colleagues. “Have our rules and regulations squeezed too much of the life out of our cities?” he asks. “But also how do you plan and design a city that is safe and functional while also leaving room for spontaneity and serendipity?”

This premise — that urban planning’s efforts to impose order risk editing out the culture, character, complexity and creative friction that makes cities cities — is a guiding theme in Messy Cities: Why We Can’t Plan Everything, a collection of essays, including Thorne’s, gathered by Toronto-based editors Zahra Ebrahim, Leslie Woo, Dylan Reid and John Lorinc. In it, they argue that “messiness is an essential element of the city.” Case studies from around the world show how imperfection can be embraced, created and preserved, from the informal street eateries of East Los Angeles to the sports facilities carved out of derelict spaces in Mumbai.

Embracing urban disorder might seem like an unlikely cause. But Woo, an urban planner and chief executive officer of the Toronto-based nonprofit CivicAction, and Reid, executive editor of Spacing magazine, offer up a series of questions that get at the heart of debates surrounding messy urbanism. In an essay about street art, they ask, “Is it ugly or creative? Does it bring disruption or diversity? Should it be left to emerge from below or be managed from above? Is it permanent or ephemeral? Does it benefit communities or just individuals? Does it create opportunity or discomfort? Are there limits around it and if so can they be effective?”

Bloomberg CityLab caught up with Woo and Ebrahim, cofounder of the public interest design studio Monumental, about why messiness in cities can be worth advocating for, and how to let the healthy kind flourish. The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You intentionally don’t give a specific definition for messy urbanism in the book, making the case that to do so would be antithetical to the idea itself. But if you were to give a general overview of the qualities and attributes you’d ascribe to messy cities, what would they be?

Leslie Woo: All of the authors included in the book brought to it some form of two things — wanting to have a sense of belonging in the places they live and trying to understand how they can have agency in their community. And what comes out of that are acts of defiance that manifest both as tiny and intimate experiences and as big gestures in cities.

Zahra Ebrahim: I think of it as where institutions end and people begin. It’s about agency. So much of the “messy” defiance is people trying to live within their cultures and identities in ways that cities don’t always create space for. We’re not trying to fetishize messiness, but we do want to acknowledge that when people feel that agency, cities become more vibrant, spontaneous and delightful.

LW: I think of the story urban planning professor Nina-Marie Lister, director of Toronto’s Ecological Design Lab, tells about fighting to keep her wild front yard habitat garden after being ordered to cut it down by the city. There was a bylaw in place intended by the municipality to control what it deemed “noxious vegetation” on private property. Lister ended up doing a public advocacy campaign to get the bylaw updated.

The phrase “messy cities” could be construed negatively but it seems like a real term of affection for the editors and authors of this book. What does it represent to you?

ZE: You can see it represented in the Bloordale neighborhood of Toronto. During lockdown in 2020, a group of local residents came together and turned a large, gravel-filled site of a demolished school into an unexpected shared space for social distancing. With handmade signage, they cheekily named the site “Bloordale Beach.” Over weeks, they and others in the community organically and spontaneously brought this imagined, landlocked beach to life, adding beach chairs, “swimming guidelines” around the puddle that had formed after a storm, even a “barkour” area for local dogs. It was both a “messy” community art project and third space, but also a place for residents to demonstrate their agency and find joy in an uncertain and difficult time.

LW: The thing that is delightful about this topic is many of these efforts are exercises in reimagining cities. Individuals and groups see a space and approach it in a different way with a spirit and ingenuity that we don’t see enough of. It’s an exercise in thinking about how we want to live. I also want to make the point that we aren’t advocating for more chaos and confusion but rather showing how these groups are attempting to make sense of where they live.

ZE: Messiness has become a wedge issue — a way to pronounce and lean into existing political cleavages. Across the world we see politicians pointing to the challenges cities face — housing affordability, transit accessibility, access to employment — and wrongfully blame or attribute these urban “messes” to specific populations and groups. We see this in the rising anti-immigrant rhetoric we hear all over the world. As an editing team, I think there was a shared understanding that multicultural and diverse societies are more successful and that when we have to navigate shared social and cultural space, it’s better for society.

This is also not all about the failure of institutions to serve the needs of the public. Some of this is about groups responding to failures of the present and shaping a better future. And some of what we’re talking about is people seeing opportunities to make the type of “mess” that would support their community to thrive, like putting a pop-up market and third space in a strip mall parking lot, and creating a space for people to come together.

You and the rest of the editors are based in Toronto and the city comes up recurrently in the book. What makes the city such an interesting case study in messy urbanism?

ZE: Toronto is what a local journalist, Doug Saunders, calls an “arrival city” — one in three newcomers in Canada land in Toronto. These waves of migration are encoded in our city’s DNA. I think of a place like Kensington Market, where there have been successive arrivals of immigrants each decade, from Jewish and Eastern European and Italian immigrants in the early 1900s to Caribbean and Chinese immigrants in the 1960s and ’70s.

Kensington continues to be one of the most vibrant urban spaces in the city. You’ve got the market, food vendors, shops and semi-informal commercial activity, cultural venues and jazz bars. In so many parts of Toronto you can’t see the history on the street but in Kensington you can see the palimpsest and layers of change it’s lived through. There is development pressure in every direction and major retailers opening nearby but it remains this vibrant representation of different eras of newcomers in Toronto and what they needed — socially, culturally and commercially. It’s a great example of where the formal and informal, the planned and unplanned meet. Every nook and cranny is filled with a story, with locals making a “mess,” but really just expressing their agency.

LW: This messy urbanism can also be seen in Toronto’s apartment tower communities that were built in the 1960s. These buildings have experienced periods of neglect and changes in ownership. But today when moving from floor to floor, it feels like traveling around the entire world; you can move from the Caribbean to continental Africa to the Middle East. These are aerial cities in and of themselves. They’re a great example of people taking a place where the conditions aren’t ideal and telling their own different story — it’s everything from the music to the food to the languages.

You didn’t include any case studies or essays from Europe in the book. Why did you make that choice, and what does an overreliance on looking to cities like Copenhagen do to the way we think of and plan for cities?

LW: When I trained as an urban planner and architect, all the pedagogy was very Eurocentric — it was Spain, France and Greece. But if we want to reframe how we think about cities, we need to reframe our points of reference.

ZE: During our editorial meetings we talked about how the commonly accepted ideas about urban order that we know are Eurocentric by design, and don’t represent the multitude of people that live in cities and what “order” may mean to them. Again, it’s not to celebrate chaos but rather to say there are different mental models of what orderliness and messiness can look like.

Go to a place like Delhi and look at the way traffic roundabouts function. There are pedestrians and cars and everybody is moving in the direction they need to move in, it’s like a river of mobility. If you’re sitting in the back of a taxi coming from North America, it looks like chaos, but to the people that live there it’s just how the city moves.

In a chapter about Mexico City’s apartment architecture, Daniel Gordon talks about what it can teach us about how to create interesting streets and neighborhoods by becoming less attached to overly prescriptive planning and instead embracing a mix of ground-floor uses and buildings with varying materials and color palettes, setbacks and heights. He argues that design guidelines can negate creativity and expression in the built environment.

In another chapter, urban geography professor Andre Sorensen talks about Tokyo, which despite being perceived as a spontaneously messy city actually operates under one of the strictest zoning systems in the world. Built forms are highly regulated, but land use mix and subdivision controls aren’t. It’s yet another example of how different urban cultures and regulatory systems work to different sets of values and conceptions of order and disorder. We tried to pay closer attention to case studies that expanded the aperture of what North American urbanism typically covers.

by Rebecca Greenwald, Bloomberg | Read more:

Image:Alfredo Martinez/Getty Images

This premise — that urban planning’s efforts to impose order risk editing out the culture, character, complexity and creative friction that makes cities cities — is a guiding theme in Messy Cities: Why We Can’t Plan Everything, a collection of essays, including Thorne’s, gathered by Toronto-based editors Zahra Ebrahim, Leslie Woo, Dylan Reid and John Lorinc. In it, they argue that “messiness is an essential element of the city.” Case studies from around the world show how imperfection can be embraced, created and preserved, from the informal street eateries of East Los Angeles to the sports facilities carved out of derelict spaces in Mumbai.

Embracing urban disorder might seem like an unlikely cause. But Woo, an urban planner and chief executive officer of the Toronto-based nonprofit CivicAction, and Reid, executive editor of Spacing magazine, offer up a series of questions that get at the heart of debates surrounding messy urbanism. In an essay about street art, they ask, “Is it ugly or creative? Does it bring disruption or diversity? Should it be left to emerge from below or be managed from above? Is it permanent or ephemeral? Does it benefit communities or just individuals? Does it create opportunity or discomfort? Are there limits around it and if so can they be effective?”

Bloomberg CityLab caught up with Woo and Ebrahim, cofounder of the public interest design studio Monumental, about why messiness in cities can be worth advocating for, and how to let the healthy kind flourish. The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You intentionally don’t give a specific definition for messy urbanism in the book, making the case that to do so would be antithetical to the idea itself. But if you were to give a general overview of the qualities and attributes you’d ascribe to messy cities, what would they be?

Leslie Woo: All of the authors included in the book brought to it some form of two things — wanting to have a sense of belonging in the places they live and trying to understand how they can have agency in their community. And what comes out of that are acts of defiance that manifest both as tiny and intimate experiences and as big gestures in cities.

Zahra Ebrahim: I think of it as where institutions end and people begin. It’s about agency. So much of the “messy” defiance is people trying to live within their cultures and identities in ways that cities don’t always create space for. We’re not trying to fetishize messiness, but we do want to acknowledge that when people feel that agency, cities become more vibrant, spontaneous and delightful.

LW: I think of the story urban planning professor Nina-Marie Lister, director of Toronto’s Ecological Design Lab, tells about fighting to keep her wild front yard habitat garden after being ordered to cut it down by the city. There was a bylaw in place intended by the municipality to control what it deemed “noxious vegetation” on private property. Lister ended up doing a public advocacy campaign to get the bylaw updated.

The phrase “messy cities” could be construed negatively but it seems like a real term of affection for the editors and authors of this book. What does it represent to you?

ZE: You can see it represented in the Bloordale neighborhood of Toronto. During lockdown in 2020, a group of local residents came together and turned a large, gravel-filled site of a demolished school into an unexpected shared space for social distancing. With handmade signage, they cheekily named the site “Bloordale Beach.” Over weeks, they and others in the community organically and spontaneously brought this imagined, landlocked beach to life, adding beach chairs, “swimming guidelines” around the puddle that had formed after a storm, even a “barkour” area for local dogs. It was both a “messy” community art project and third space, but also a place for residents to demonstrate their agency and find joy in an uncertain and difficult time.

LW: The thing that is delightful about this topic is many of these efforts are exercises in reimagining cities. Individuals and groups see a space and approach it in a different way with a spirit and ingenuity that we don’t see enough of. It’s an exercise in thinking about how we want to live. I also want to make the point that we aren’t advocating for more chaos and confusion but rather showing how these groups are attempting to make sense of where they live.

ZE: Messiness has become a wedge issue — a way to pronounce and lean into existing political cleavages. Across the world we see politicians pointing to the challenges cities face — housing affordability, transit accessibility, access to employment — and wrongfully blame or attribute these urban “messes” to specific populations and groups. We see this in the rising anti-immigrant rhetoric we hear all over the world. As an editing team, I think there was a shared understanding that multicultural and diverse societies are more successful and that when we have to navigate shared social and cultural space, it’s better for society.

This is also not all about the failure of institutions to serve the needs of the public. Some of this is about groups responding to failures of the present and shaping a better future. And some of what we’re talking about is people seeing opportunities to make the type of “mess” that would support their community to thrive, like putting a pop-up market and third space in a strip mall parking lot, and creating a space for people to come together.

You and the rest of the editors are based in Toronto and the city comes up recurrently in the book. What makes the city such an interesting case study in messy urbanism?

ZE: Toronto is what a local journalist, Doug Saunders, calls an “arrival city” — one in three newcomers in Canada land in Toronto. These waves of migration are encoded in our city’s DNA. I think of a place like Kensington Market, where there have been successive arrivals of immigrants each decade, from Jewish and Eastern European and Italian immigrants in the early 1900s to Caribbean and Chinese immigrants in the 1960s and ’70s.

Kensington continues to be one of the most vibrant urban spaces in the city. You’ve got the market, food vendors, shops and semi-informal commercial activity, cultural venues and jazz bars. In so many parts of Toronto you can’t see the history on the street but in Kensington you can see the palimpsest and layers of change it’s lived through. There is development pressure in every direction and major retailers opening nearby but it remains this vibrant representation of different eras of newcomers in Toronto and what they needed — socially, culturally and commercially. It’s a great example of where the formal and informal, the planned and unplanned meet. Every nook and cranny is filled with a story, with locals making a “mess,” but really just expressing their agency.

LW: This messy urbanism can also be seen in Toronto’s apartment tower communities that were built in the 1960s. These buildings have experienced periods of neglect and changes in ownership. But today when moving from floor to floor, it feels like traveling around the entire world; you can move from the Caribbean to continental Africa to the Middle East. These are aerial cities in and of themselves. They’re a great example of people taking a place where the conditions aren’t ideal and telling their own different story — it’s everything from the music to the food to the languages.

You didn’t include any case studies or essays from Europe in the book. Why did you make that choice, and what does an overreliance on looking to cities like Copenhagen do to the way we think of and plan for cities?

LW: When I trained as an urban planner and architect, all the pedagogy was very Eurocentric — it was Spain, France and Greece. But if we want to reframe how we think about cities, we need to reframe our points of reference.

ZE: During our editorial meetings we talked about how the commonly accepted ideas about urban order that we know are Eurocentric by design, and don’t represent the multitude of people that live in cities and what “order” may mean to them. Again, it’s not to celebrate chaos but rather to say there are different mental models of what orderliness and messiness can look like.

Go to a place like Delhi and look at the way traffic roundabouts function. There are pedestrians and cars and everybody is moving in the direction they need to move in, it’s like a river of mobility. If you’re sitting in the back of a taxi coming from North America, it looks like chaos, but to the people that live there it’s just how the city moves.

In a chapter about Mexico City’s apartment architecture, Daniel Gordon talks about what it can teach us about how to create interesting streets and neighborhoods by becoming less attached to overly prescriptive planning and instead embracing a mix of ground-floor uses and buildings with varying materials and color palettes, setbacks and heights. He argues that design guidelines can negate creativity and expression in the built environment.

In another chapter, urban geography professor Andre Sorensen talks about Tokyo, which despite being perceived as a spontaneously messy city actually operates under one of the strictest zoning systems in the world. Built forms are highly regulated, but land use mix and subdivision controls aren’t. It’s yet another example of how different urban cultures and regulatory systems work to different sets of values and conceptions of order and disorder. We tried to pay closer attention to case studies that expanded the aperture of what North American urbanism typically covers.

by Rebecca Greenwald, Bloomberg | Read more:

Image:Alfredo Martinez/Getty Images

[ed. Give me a messy city any day, or at least one with a few messy parts.]

Tuesday, February 3, 2026

These Four States Are in Denial Over a Looming Water Crisis

Lake Mead is two-thirds empty. Lake Powell is even emptier.

Not for the first time, the seven Western states that rely on the Colorado River are fighting over how to keep these reservoirs from crashing — an event that could spur water shortages from Denver to Las Vegas to Los Angeles.

The tens of millions of people who rely on the Colorado River have weathered such crises before, even amid a stubborn quarter-century megadrought fueled by climate change. The states have always struck deals to use less water, overcoming their political differences to avert “dead pool” at Mead and Powell, meaning that water could no longer flow downstream.

This time, a deal may not be possible. And it’s clear who’s to blame.

Not the farmers who grow alfalfa and other feed for animals, despite the fact that they use one-third of all water in the Colorado River basin. Not California, even though the Golden State uses more river water than any of its neighbors. Not even the Trump administration, which has done a lousy job pressing the states to compromise.

No, the Upper Basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming have emerged as the main obstacles to a fair deal. They’ve gummed up negotiations by refusing to accept mandatory cuts of any amount — unlike the Lower Basin states, which have spent years slashing water use.

Upper Basin leaders have long harbored ambitions of using more water to fuel economic development, especially in cities. “There’s this notion of keeping the dream of growth alive,” said John Fleck, a researcher at the University of New Mexico. “It’s difficult for people to reckon with the reality that they can’t keep that dream alive anymore.”

Federal officials have set a Feb. 14 deadline for the seven states to reach consensus, although negotiators blew past a November deadline with no consequence. The real cutoff is the end of 2026, when longstanding rules for assigning cuts to avoid shortages will expire.

Low snowpack levels across the Western United States this winter are raising the stakes. In some ways, though, the conflict is a century in the making.

Since 1922, the states have divvied up water under the Colorado River Compact, which gave 7.5 million acre-feet annually to the Lower Basin and 7.5 million acre-feet to the Upper Basin. Most water originates as Rocky Mountain snowmelt before flowing downstream to Lake Powell near the Utah-Arizona border. Once released from Powell, it flows through the Grand Canyon to Lake Mead, near Las Vegas.

But even though the two groups of states agreed to split the water evenly, Los Angeles and Phoenix grew bigger and faster than Denver and Salt Lake City, gobbling up more water. Lower Basin farmers and ranchers, too, used far more water than their Upper Basin counterparts — especially growers in California’s Imperial Valley, who staked out some of the river’s oldest and thus highest-priority water rights.

Global warming had other plans, too. There was never as much water in the river as negotiators assumed even back in 1922 — a fact that scientists knew at the time. The states spent decades outrunning that original sin by finding creative ways to conserve water when drought struck. But deal-making was easier when the river averaged, say, 13 million acre-feet. Over the past six years, as the effects of burning fossil fuels have mounted, flows averaged just 10.8 million acre-feet. That means the states will need to make much deeper cuts.

So far, no luck. The Upper and Lower Basins have spent several years at fierce loggerheads, with some negotiators growing vitriolic. State officials are still talking, most recently at a Jan. 30 meeting convened by Interior Secretary Doug Burgum. But after two decades of collaborative problem-solving, longtime observers say they’ve never seen so much animosity.

Lower Basin officials largely blame Colorado, the de facto leader of the Upper Basin. They say Colorado won’t budge from what they consider the extreme legal position that the Upper Basin bears no responsibility for delivering water downstream from Powell to Mead for the Lower Basin’s use. They also fault Colorado for demanding that mandatory cuts fall entirely on the Lower Basin.

Upper Basin officials tell a different story. They insist that California and Arizona have been overconsuming water — and by their reading of the compact, that means it’s not their job to keep replenishing the Lower Basin’s savings account at Lake Mead. They also say it would be unfair to force them to cut back when California and Arizona are the real water hogs.

On the one hand, the numbers don’t lie: The Lower Basin states used nearly 6.1 million acre-feet in 2024, compared with the Upper Basin’s nearly 4.5 million, according to the federal government. The Imperial Irrigation District — which supplies farmers who grow alfalfa, broccoli, onions and other crops — used more water than the entire state of Colorado.

On the other hand, the Lower Basin has done far more to cut back than the Upper Basin. Los Angeles and Las Vegas residents have torn out grass lawns en masse; Vegas has water cops to police excessive water use by sprinkler systems. Farmers in Arizona and California are leaving fields dry, sometimes aided by federal incentive programs. California is investing in expensive wastewater recycling to reduce its dependence on imported water.

Mr. Fleck projected that the Lower Basin’s Colorado River consumption in 2025 would be its lowest since 1983. Imperial’s consumption would be its lowest since at least 1941.

California, Arizona and Nevada still waste plenty of water, but they’re prepared to go further. They’ve told the Upper Basin that as part of a post-2026 deal, they’re willing to reduce consumption by an additional 1.25 million acre-feet of water — but only if the Upper Basin shares the pain of further cuts during especially dry years.

Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming do not want to share the pain — at least not through mandatory cuts. They say they already cut back voluntarily during drought years, although independent experts are skeptical. They also say the Lower Basin states use more water than federal data show — something like 10 million acre-feet.

When I asked Becky Mitchell, Colorado’s lead negotiator, if her state plans to keep growing, she responded with an alarming comparison to the Lower Basin, musing that the Upper Basin would probably never use 10 million acre-feet. Thank goodness, because that kind of growth would more than bankrupt the Colorado River.

But even as she acknowledged that the Upper Basin states “have to live within hydrology,” she suggested they have a right to use more water.

“The compact gave us the protection to grow and develop at our own pace,” she said.

by Sammy Roth, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Jim Morgan

[ed. Hard to feel sorry for Arizona and Nevada who've been building like crazy over the last few decades.]

Not for the first time, the seven Western states that rely on the Colorado River are fighting over how to keep these reservoirs from crashing — an event that could spur water shortages from Denver to Las Vegas to Los Angeles.

The tens of millions of people who rely on the Colorado River have weathered such crises before, even amid a stubborn quarter-century megadrought fueled by climate change. The states have always struck deals to use less water, overcoming their political differences to avert “dead pool” at Mead and Powell, meaning that water could no longer flow downstream.

This time, a deal may not be possible. And it’s clear who’s to blame.

Not the farmers who grow alfalfa and other feed for animals, despite the fact that they use one-third of all water in the Colorado River basin. Not California, even though the Golden State uses more river water than any of its neighbors. Not even the Trump administration, which has done a lousy job pressing the states to compromise.

No, the Upper Basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming have emerged as the main obstacles to a fair deal. They’ve gummed up negotiations by refusing to accept mandatory cuts of any amount — unlike the Lower Basin states, which have spent years slashing water use.

Upper Basin leaders have long harbored ambitions of using more water to fuel economic development, especially in cities. “There’s this notion of keeping the dream of growth alive,” said John Fleck, a researcher at the University of New Mexico. “It’s difficult for people to reckon with the reality that they can’t keep that dream alive anymore.”

Federal officials have set a Feb. 14 deadline for the seven states to reach consensus, although negotiators blew past a November deadline with no consequence. The real cutoff is the end of 2026, when longstanding rules for assigning cuts to avoid shortages will expire.

Low snowpack levels across the Western United States this winter are raising the stakes. In some ways, though, the conflict is a century in the making.

Since 1922, the states have divvied up water under the Colorado River Compact, which gave 7.5 million acre-feet annually to the Lower Basin and 7.5 million acre-feet to the Upper Basin. Most water originates as Rocky Mountain snowmelt before flowing downstream to Lake Powell near the Utah-Arizona border. Once released from Powell, it flows through the Grand Canyon to Lake Mead, near Las Vegas.

But even though the two groups of states agreed to split the water evenly, Los Angeles and Phoenix grew bigger and faster than Denver and Salt Lake City, gobbling up more water. Lower Basin farmers and ranchers, too, used far more water than their Upper Basin counterparts — especially growers in California’s Imperial Valley, who staked out some of the river’s oldest and thus highest-priority water rights.

Global warming had other plans, too. There was never as much water in the river as negotiators assumed even back in 1922 — a fact that scientists knew at the time. The states spent decades outrunning that original sin by finding creative ways to conserve water when drought struck. But deal-making was easier when the river averaged, say, 13 million acre-feet. Over the past six years, as the effects of burning fossil fuels have mounted, flows averaged just 10.8 million acre-feet. That means the states will need to make much deeper cuts.

So far, no luck. The Upper and Lower Basins have spent several years at fierce loggerheads, with some negotiators growing vitriolic. State officials are still talking, most recently at a Jan. 30 meeting convened by Interior Secretary Doug Burgum. But after two decades of collaborative problem-solving, longtime observers say they’ve never seen so much animosity.

Lower Basin officials largely blame Colorado, the de facto leader of the Upper Basin. They say Colorado won’t budge from what they consider the extreme legal position that the Upper Basin bears no responsibility for delivering water downstream from Powell to Mead for the Lower Basin’s use. They also fault Colorado for demanding that mandatory cuts fall entirely on the Lower Basin.

Upper Basin officials tell a different story. They insist that California and Arizona have been overconsuming water — and by their reading of the compact, that means it’s not their job to keep replenishing the Lower Basin’s savings account at Lake Mead. They also say it would be unfair to force them to cut back when California and Arizona are the real water hogs.

On the one hand, the numbers don’t lie: The Lower Basin states used nearly 6.1 million acre-feet in 2024, compared with the Upper Basin’s nearly 4.5 million, according to the federal government. The Imperial Irrigation District — which supplies farmers who grow alfalfa, broccoli, onions and other crops — used more water than the entire state of Colorado.

On the other hand, the Lower Basin has done far more to cut back than the Upper Basin. Los Angeles and Las Vegas residents have torn out grass lawns en masse; Vegas has water cops to police excessive water use by sprinkler systems. Farmers in Arizona and California are leaving fields dry, sometimes aided by federal incentive programs. California is investing in expensive wastewater recycling to reduce its dependence on imported water.

Mr. Fleck projected that the Lower Basin’s Colorado River consumption in 2025 would be its lowest since 1983. Imperial’s consumption would be its lowest since at least 1941.

California, Arizona and Nevada still waste plenty of water, but they’re prepared to go further. They’ve told the Upper Basin that as part of a post-2026 deal, they’re willing to reduce consumption by an additional 1.25 million acre-feet of water — but only if the Upper Basin shares the pain of further cuts during especially dry years.

Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming do not want to share the pain — at least not through mandatory cuts. They say they already cut back voluntarily during drought years, although independent experts are skeptical. They also say the Lower Basin states use more water than federal data show — something like 10 million acre-feet.

When I asked Becky Mitchell, Colorado’s lead negotiator, if her state plans to keep growing, she responded with an alarming comparison to the Lower Basin, musing that the Upper Basin would probably never use 10 million acre-feet. Thank goodness, because that kind of growth would more than bankrupt the Colorado River.

But even as she acknowledged that the Upper Basin states “have to live within hydrology,” she suggested they have a right to use more water.

“The compact gave us the protection to grow and develop at our own pace,” she said.

by Sammy Roth, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Jim Morgan

[ed. Hard to feel sorry for Arizona and Nevada who've been building like crazy over the last few decades.]

Friday, January 30, 2026

Hawaiʻi Could See Nation’s Highest Drop In High School Graduates

Hawaiʻi Could See Nation’s Highest Drop In High School Graduates (CB)

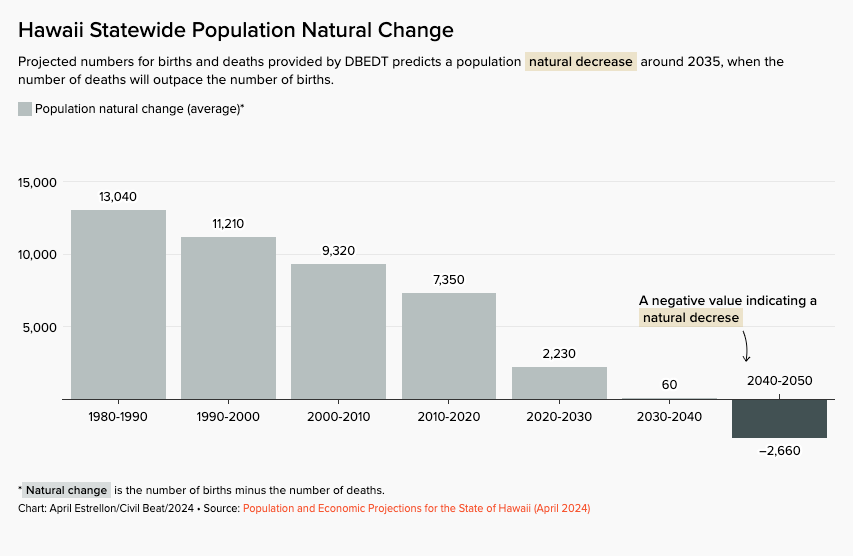

Hawaiʻi is expected to see the greatest decline in high school graduates in the nation over the next several years, raising concerns from lawmakers and Department of Education officials about the future of small schools in shrinking communities.

Between 2023 and 2041, Hawaiʻi could see a 33% drop in the number of students graduating from high school, according to the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. The nation as a whole is projected to see a 10% drop in graduates, according to the commission’s most recent report, published at the end of 2024.

Image: Chart: Megan Tagami/Civil BeatSource: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education

Hawaiʻi is expected to see the greatest decline in high school graduates in the nation over the next several years, raising concerns from lawmakers and Department of Education officials about the future of small schools in shrinking communities.

Between 2023 and 2041, Hawaiʻi could see a 33% drop in the number of students graduating from high school, according to the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. The nation as a whole is projected to see a 10% drop in graduates, according to the commission’s most recent report, published at the end of 2024.

Image: Chart: Megan Tagami/Civil BeatSource: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education

Monday, January 26, 2026

Three Columnists on ICE in Minneapolis

Matthew Rose, an Opinion editorial director, hosted an online conversation with three Opinion columnists.

Matthew Rose: On Saturday, agents from the border patrol in Minneapolis shot and killed Alex Pretti, an American citizen. We don’t have a full accounting of what happened, but the available video evidence shows he was filming the agents with his phone, as many locals have done since the full weight of federal immigration enforcement descended on the city.

Lydia, you’ve been to Minneapolis recently. Tell us what you saw and give us some context for what just happened.

Lydia Polgreen: I have never been a fan of the conceit of American journalists covering the United States as if it were a backwater foreign nation, but in Minneapolis last week I could not shake the impulse to compare my experiences in a city I know so well (I spent a chunk of my childhood in the Twin Cities, and my father is from Minneapolis) with my experiences covering civil wars in places like Congo, Sudan, Sri Lanka and more. Watching the video of Pretti’s killing, I thought: If this was happening on the streets of any of those places, I would not hesitate to call it an extrajudicial execution by security forces. This is where we are: armed agents of the state killing civilians with an apparent belief in their total impunity.

Lydia, you’ve been to Minneapolis recently. Tell us what you saw and give us some context for what just happened.

Lydia Polgreen: I have never been a fan of the conceit of American journalists covering the United States as if it were a backwater foreign nation, but in Minneapolis last week I could not shake the impulse to compare my experiences in a city I know so well (I spent a chunk of my childhood in the Twin Cities, and my father is from Minneapolis) with my experiences covering civil wars in places like Congo, Sudan, Sri Lanka and more. Watching the video of Pretti’s killing, I thought: If this was happening on the streets of any of those places, I would not hesitate to call it an extrajudicial execution by security forces. This is where we are: armed agents of the state killing civilians with an apparent belief in their total impunity.

I left before Pretti was gunned down, apparently in the back while he was on his knees. What I saw was so reminiscent of other conflicts — civilians doing their very best to protect themselves and their neighbors from seemingly random violence meted out by state agents. Those agents, masked and heavily armed, are roaming the streets and picking up and assaulting people for having the wrong skin color or accent, or being engaged in the constitutionally protected acts of filming, observing or protesting their presence. Anyone who knows me knows that I am allergic to hyperbole, but sometimes you need to simply call a spade a spade. This is a lawless operation.

David French: We are witnessing the total breakdown of any meaningful system of accountability for federal officials. The combination of President Trump’s Jan. 6 pardons, his ongoing campaign of pardoning friends and allies, his politicized prosecutions and now his administration’s assurances that federal officers have immunity are creating a new legal reality in the United States. The national government is becoming functionally lawless, and the legal system is struggling to contain his corruption.

We’re tasting the bitter fruit of Trump’s dreadful policies, to be sure, but it’s worse than that. He’s exploiting years of legal developments that have helped insulate federal officials from both criminal and civil accountability. It’s as if we engineered a legal system premised on the idea that federal officials are almost always honest, and the citizens who critique them are almost always wrong. We’ve tilted the legal playing field against citizens and in favor of the government.

The Trump administration breaks the law, and also ruthlessly exploits all the immunities it’s granted by law. The situation is unsustainable for a constitutional republic.

Michelle Goldberg: The administration is very consciously reinforcing that sense of impunity. First there was Stephen Miller addressing the security forces after one of them killed Renee Good: “To all ICE officers: You have federal immunity in the conduct of your duties.” On Sunday, Greg Bovino, the self-consciously villainous border patrol commander, praised the agents who executed Pretti.

I wish people weren’t allowed to carry guns in public. But they are, and after watching Republicans bring semiautomatic weapons to protest Covid closures and make a hero of Kyle Rittenhouse, it’s wild to hear the head of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Kash Patel, say, on Fox News, “You cannot bring a firearm, loaded, with multiple magazines, to any sort of protest that you want.” The point here isn’t hypocrisy; it’s them nakedly asserting that constitutional rights are for us, not you.

Rose: David, I wanted to pick up on your description of the federal government as lawless. As you’ve written, we seem to be in the world described by the Nazi-era Jewish labor lawyer Ernst Fraenkel and what he called “the dual state.” There is one we live in, where we pay taxes and go to work, and life seems to work according to common rules, and the other where the rules no longer apply. Is this what we’re experiencing?

French: We’re living in a version of the dual state. Not to the same extent as the Nazis, of course, but Fraenkel’s framing is still relevant. The Nazis didn’t create their totalitarian state immediately. Instead, they were able to lull much of the population to sleep just by keeping their lives relatively normal. As you say, they went to work, paid their taxes, entered into contracts and did all the things you normally do in a functioning nation. But if you crossed the government, then you passed into a different state entirely, where you would feel the full weight of fascist power — regardless of the rule of law.

One of the saddest things about the killings of Good and Pretti is that you could tell that neither of them seemed to know the danger until it was too late. They believed they were operating in some version of the normal state (what Fraenkel called the “normative state”) where the police usually respond with discipline and restraint.

Good and Pretti both had calm demeanors. They may have been annoying federal officers, but nothing about their posture indicated the slightest threat. Good even said, “I’m not mad” to the man who would gun her down seconds later. Pretti was filming with his phone in one hand and he had the other hand in the air as he was pepper-sprayed and tackled.

The officers, however, were in that different state, what Fraenkel called the “prerogative state,” where the government is a law unto itself. The officers acted violently, with impunity, and the government immediately acted to defend them and slander their victims. As the prerogative state expands, the normative state shrinks, and our lives often change before we can grasp what happened. (...)

Rose: With immigration enforcement in Trump’s second term, we have a quasi-military force, backed by more funding than most countries give their actual militaries, deployed for the most part to enforce civil, not criminal law. Should we instead think about this as spectacle? Caitlin Dickerson of The Atlantic, interviewed by our colleague Ezra Klein, argued that immigration enforcement under Trump is being implemented for maximum visual impact.

Goldberg: That’s increasingly the critique of conservatives who don’t want to break with Trump, but also are having a hard time rationalizing ICE’s violence in Minneapolis. Erick Erickson blames what’s happening in Minnesota on the D.H.S. secretary, Kristi Noem, marginalizing Tom Homan, the border czar, in favor of Greg Bovino from Customs and Border Protection, who clearly relishes street-level confrontation.

And the administration obviously wants to make a spectacle. We don’t know why the guy who shot Renee Good was filming, but it could well have been to feed their insatiable demand for content, which in turn is feeding their recruiting efforts. Did any of you see the clip where one of the agents shooting tear gas at protesters can be heard saying, “It’s like ‘Call of Duty.’ So cool, huh?”