Claude Lalanne,‘Ginkgo’ Chairs, 1999

via:

Showing posts with label Design. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Design. Show all posts

Tuesday, February 24, 2026

Friday, February 20, 2026

Kung Fu Robots Steal the Show

Dozens of G1 robots from Unitree Robotics delivered the world's first fully autonomous humanoid robot kung fu performance, featuring rapid position changes. The show pushed the limits of robotic movement and set multiple global records.

[ed. Not your mom's old roomba anymore. Robotics + AI the next frontier.]

Tuesday, February 10, 2026

Claude's New Constitution

We’re publishing a new constitution for our AI model, Claude. It’s a detailed description of Anthropic’s vision for Claude’s values and behavior; a holistic document that explains the context in which Claude operates and the kind of entity we would like Claude to be.

The constitution is a crucial part of our model training process, and its content directly shapes Claude’s behavior. Training models is a difficult task, and Claude’s outputs might not always adhere to the constitution’s ideals. But we think that the way the new constitution is written—with a thorough explanation of our intentions and the reasons behind them—makes it more likely to cultivate good values during training.

In this post, we describe what we’ve included in the new constitution and some of the considerations that informed our approach...

What is Claude’s Constitution?

Claude’s constitution is the foundational document that both expresses and shapes who Claude is. It contains detailed explanations of the values we would like Claude to embody and the reasons why. In it, we explain what we think it means for Claude to be helpful while remaining broadly safe, ethical, and compliant with our guidelines. The constitution gives Claude information about its situation and offers advice for how to deal with difficult situations and tradeoffs, like balancing honesty with compassion and the protection of sensitive information. Although it might sound surprising, the constitution is written primarily for Claude. It is intended to give Claude the knowledge and understanding it needs to act well in the world.

We treat the constitution as the final authority on how we want Claude to be and to behave—that is, any other training or instruction given to Claude should be consistent with both its letter and its underlying spirit. This makes publishing the constitution particularly important from a transparency perspective: it lets people understand which of Claude’s behaviors are intended versus unintended, to make informed choices, and to provide useful feedback. We think transparency of this kind will become ever more important as AIs start to exert more influence in society1.

We use the constitution at various stages of the training process. This has grown out of training techniques we’ve been using since 2023, when we first began training Claude models using Constitutional AI. Our approach has evolved significantly since then, and the new constitution plays an even more central role in training.

Claude itself also uses the constitution to construct many kinds of synthetic training data, including data that helps it learn and understand the constitution, conversations where the constitution might be relevant, responses that are in line with its values, and rankings of possible responses. All of these can be used to train future versions of Claude to become the kind of entity the constitution describes. This practical function has shaped how we’ve written the constitution: it needs to work both as a statement of abstract ideals and a useful artifact for training.

Our new approach to Claude’s Constitution

Our previous Constitution was composed of a list of standalone principles. We’ve come to believe that a different approach is necessary. We think that in order to be good actors in the world, AI models like Claude need to understand why we want them to behave in certain ways, and we need to explain this to them rather than merely specify what we want them to do. If we want models to exercise good judgment across a wide range of novel situations, they need to be able to generalize—to apply broad principles rather than mechanically following specific rules.

Specific rules and bright lines sometimes have their advantages. They can make models’ actions more predictable, transparent, and testable, and we do use them for some especially high-stakes behaviors in which Claude should never engage (we call these “hard constraints”). But such rules can also be applied poorly in unanticipated situations or when followed too rigidly2. We don’t intend for the constitution to be a rigid legal document—and legal constitutions aren’t necessarily like this anyway.

The constitution reflects our current thinking about how to approach a dauntingly novel and high-stakes project: creating safe, beneficial non-human entities whose capabilities may come to rival or exceed our own. Although the document is no doubt flawed in many ways, we want it to be something future models can look back on and see as an honest and sincere attempt to help Claude understand its situation, our motives, and the reasons we shape Claude in the ways we do.

The constitution is a crucial part of our model training process, and its content directly shapes Claude’s behavior. Training models is a difficult task, and Claude’s outputs might not always adhere to the constitution’s ideals. But we think that the way the new constitution is written—with a thorough explanation of our intentions and the reasons behind them—makes it more likely to cultivate good values during training.

In this post, we describe what we’ve included in the new constitution and some of the considerations that informed our approach...

What is Claude’s Constitution?

Claude’s constitution is the foundational document that both expresses and shapes who Claude is. It contains detailed explanations of the values we would like Claude to embody and the reasons why. In it, we explain what we think it means for Claude to be helpful while remaining broadly safe, ethical, and compliant with our guidelines. The constitution gives Claude information about its situation and offers advice for how to deal with difficult situations and tradeoffs, like balancing honesty with compassion and the protection of sensitive information. Although it might sound surprising, the constitution is written primarily for Claude. It is intended to give Claude the knowledge and understanding it needs to act well in the world.

We treat the constitution as the final authority on how we want Claude to be and to behave—that is, any other training or instruction given to Claude should be consistent with both its letter and its underlying spirit. This makes publishing the constitution particularly important from a transparency perspective: it lets people understand which of Claude’s behaviors are intended versus unintended, to make informed choices, and to provide useful feedback. We think transparency of this kind will become ever more important as AIs start to exert more influence in society1.

We use the constitution at various stages of the training process. This has grown out of training techniques we’ve been using since 2023, when we first began training Claude models using Constitutional AI. Our approach has evolved significantly since then, and the new constitution plays an even more central role in training.

Claude itself also uses the constitution to construct many kinds of synthetic training data, including data that helps it learn and understand the constitution, conversations where the constitution might be relevant, responses that are in line with its values, and rankings of possible responses. All of these can be used to train future versions of Claude to become the kind of entity the constitution describes. This practical function has shaped how we’ve written the constitution: it needs to work both as a statement of abstract ideals and a useful artifact for training.

Our new approach to Claude’s Constitution

Our previous Constitution was composed of a list of standalone principles. We’ve come to believe that a different approach is necessary. We think that in order to be good actors in the world, AI models like Claude need to understand why we want them to behave in certain ways, and we need to explain this to them rather than merely specify what we want them to do. If we want models to exercise good judgment across a wide range of novel situations, they need to be able to generalize—to apply broad principles rather than mechanically following specific rules.

Specific rules and bright lines sometimes have their advantages. They can make models’ actions more predictable, transparent, and testable, and we do use them for some especially high-stakes behaviors in which Claude should never engage (we call these “hard constraints”). But such rules can also be applied poorly in unanticipated situations or when followed too rigidly2. We don’t intend for the constitution to be a rigid legal document—and legal constitutions aren’t necessarily like this anyway.

The constitution reflects our current thinking about how to approach a dauntingly novel and high-stakes project: creating safe, beneficial non-human entities whose capabilities may come to rival or exceed our own. Although the document is no doubt flawed in many ways, we want it to be something future models can look back on and see as an honest and sincere attempt to help Claude understand its situation, our motives, and the reasons we shape Claude in the ways we do.

by Anthropic | Read more:

Image: Anthropic

[ed. I have an inclination to distrust AI companies, mostly because their goals (other than advancing technology) appear strongly directed at achieving market dominance and winning some (undefined) race to AGI. Anthropic is different. They actually seem legitimately concerned with the ethical implications of building another bomb that could potentially destroy humanity, or at minimum a large degree of human agency, and are aware of the responsibilities that go along with that. This is a well thought out and necessary document that hopefully other companies will follow and improve on, and that governments can use to develop more well-informed regulatory oversight in the future. See also: The New Politics of the AI Apocalypse; and, The Anthropic Hive Mind (Medim).

Labels:

Business,

Critical Thought,

Design,

Education,

Philosophy,

Psychology,

Relationships,

Technology

Thursday, February 5, 2026

The Questionable Science Behind the Odd-Looking Football Helmets

The N.F.L. claims Guardian Caps reduce the risk of concussions. The company that makes them says, “It has nothing to do with concussions.”

The first time Jared Wilson, a New England Patriots offensive lineman, is seen on the Super Bowl broadcast on Sunday, some viewers may wonder why he has such a big helmet.

It’s called a Guardian Cap, and Mr. Wilson is among about two dozen National Football League players who have worn the helmet covering in games this season. Not for comfort or style. Even the company that makes the cap acknowledges that it’s bulky and ugly. Rather, Wilson and others have worn it for its purported safety benefits.

The N.F.L. claims the cartoonish caps reduce the risk of getting a concussion, convincing some players that they are worth wearing. The company that designed and manufactures Guardian Caps, though, makes no such claim.

“No helmet, headgear or chin strap can prevent or eliminate the risk of concussions or other serious head injuries while playing sports or otherwise,” the product’s disclaimer warns. Instead, the company says its caps blunt the impact of smaller hits to the head that are linked to long-term brain damage.

“It has nothing to do with concussions,” said Erin Hanson, a co-founder of Guardian Sports, the Atlanta-area company that makes the cap. “We call concussions ‘the C word.’ This is about reducing the impact of all those hits every time. That’s all that was.”

The disconnect between the N.F.L.’s claims about the Guardian Caps and what the company promises is emblematic of the messy line between promotion and protection, and the power of the N.F.L. to sway football coaches and players trying to insulate themselves from the dangers of the sport.

An endorsement by the N.F.L., the country’s most visible and powerful sports league, can generate millions of dollars in sales for equipment makers, including Guardian Sports. The N.F.L.’s embrace of the caps, beginning in 2022, has led to a surge in orders from youth leagues to pro teams. About half a million players at all levels now wear them, Guardian Sports said.

“Anything I can do to save my brain, save my head,” said Kevin Dotson, an offensive lineman on the Los Angeles Rams who has worn the cap in games since last season.

Ms. Hanson said the company had struggled with whether to promote the N.F.L.’s claims about concussions. It decided to do so because the N.F.L.’s boasts might persuade young players to use the product, even if the benefits are not comparable. (...)

Guardian Caps are the latest in a wave of products that have emerged since researchers linked the sport to the progressive brain disease known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or C.T.E. Scores of companies have introduced equipment that purports to prevent head injuries, from a silicone collar worn around a player’s neck, known as the Q-Collar, which is promoted as a way to give the brain an extra layer of cushioning, to G8RSkin Shiesty, a head covering that is worn under helmets and promises to significantly reduce concussion risk.

Independent neurologists are generally skeptical, if not outright dismissive, of the benefits of any product claiming to reduce concussions because few rigorous studies have been done to demonstrate their effectiveness.

Few products have received as much publicity as the Guardian Cap, though. Sales of the caps, which were introduced in 2012, took off after the company won the N.F.L.’s HeadHealthTECH Challenge in 2017 — two years after the league settled a lawsuit brought by more than 5,000 former players who accused the N.F.L. of hiding from them the dangers of concussions.

Guardian Sports received $20,000 from the league for additional testing, but the N.F.L.’s endorsement was priceless.

Orders for the caps from colleges, high schools and youth teams poured in. Nearly every college team in the top ranks practices with the caps. In 2021, researchers, including some affiliated with the N.F.L. and its players’ union, published a paper that said Guardian Caps reduced “head impact severity” by 9 percent.

That year, Guardian Sports introduced its NXT model, with an extra layer of padding for bigger, stronger players. The N.F.L. required linemen, tight ends and linebackers to wear them in training camp. In 2023, the mandate expanded to all contact practices, and running backs and fullbacks were added. Starting in 2024, wide receivers and defensive backs had to wear them in practices, and players could wear them in games. (...)

Researchers at Virginia Tech, which runs a well-regarded helmet-testing laboratory, found that players who wore the NXT version of the Guardian Cap experienced a 14 percent decline in rotational accelerations — basically, the turning of the head — and that their concussion risk was 34 percent lower than for players who wore only helmets.

The benefits were significantly lower for players who wore the XT, the model worn in youth leagues and high schools. Rotational acceleration was only 5 percent lower, and the concussion risk was reduced by 15 percent.

Stefan Duma, who leads the lab, said the smaller reductions, combined with better helmets and fewer full contact practices, suggested that the benefits of wearing the XT were negligible.

“We tested it thoroughly, and the benefits are just not there,” Dr. Duma said. “It’s all noise, no statistical difference in youth.”

Most parents and coaches, though, do not read research reports from testing labs, and there is little information on the Guardian Sports website that explains the difference in performance between the XT and NXT models. But looking at the testimonials on the website from Mr. Goodell and other N.F.L. luminaries, parents and coaches might believe they were buying the cap worn by the pros.

It’s called a Guardian Cap, and Mr. Wilson is among about two dozen National Football League players who have worn the helmet covering in games this season. Not for comfort or style. Even the company that makes the cap acknowledges that it’s bulky and ugly. Rather, Wilson and others have worn it for its purported safety benefits.

The N.F.L. claims the cartoonish caps reduce the risk of getting a concussion, convincing some players that they are worth wearing. The company that designed and manufactures Guardian Caps, though, makes no such claim.

“No helmet, headgear or chin strap can prevent or eliminate the risk of concussions or other serious head injuries while playing sports or otherwise,” the product’s disclaimer warns. Instead, the company says its caps blunt the impact of smaller hits to the head that are linked to long-term brain damage.

“It has nothing to do with concussions,” said Erin Hanson, a co-founder of Guardian Sports, the Atlanta-area company that makes the cap. “We call concussions ‘the C word.’ This is about reducing the impact of all those hits every time. That’s all that was.”

The disconnect between the N.F.L.’s claims about the Guardian Caps and what the company promises is emblematic of the messy line between promotion and protection, and the power of the N.F.L. to sway football coaches and players trying to insulate themselves from the dangers of the sport.

An endorsement by the N.F.L., the country’s most visible and powerful sports league, can generate millions of dollars in sales for equipment makers, including Guardian Sports. The N.F.L.’s embrace of the caps, beginning in 2022, has led to a surge in orders from youth leagues to pro teams. About half a million players at all levels now wear them, Guardian Sports said.

“Anything I can do to save my brain, save my head,” said Kevin Dotson, an offensive lineman on the Los Angeles Rams who has worn the cap in games since last season.

The league claimed that the Guardian Cap had helped reduce concussions by more than 50 percent, which has put the company in the awkward position of embracing the spirit of the endorsement while distancing itself from the facts of it. Further complicating the situation: The model worn by pro and college players, the NXT, is not the same as the company’s mass-market product, the XT, which retails for $75. That model has less padding than the NXT, and may be less effective at limiting the impact of hits to the head, studies have shown.

Ms. Hanson said the company had struggled with whether to promote the N.F.L.’s claims about concussions. It decided to do so because the N.F.L.’s boasts might persuade young players to use the product, even if the benefits are not comparable. (...)

Guardian Caps are the latest in a wave of products that have emerged since researchers linked the sport to the progressive brain disease known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or C.T.E. Scores of companies have introduced equipment that purports to prevent head injuries, from a silicone collar worn around a player’s neck, known as the Q-Collar, which is promoted as a way to give the brain an extra layer of cushioning, to G8RSkin Shiesty, a head covering that is worn under helmets and promises to significantly reduce concussion risk.

Independent neurologists are generally skeptical, if not outright dismissive, of the benefits of any product claiming to reduce concussions because few rigorous studies have been done to demonstrate their effectiveness.

Few products have received as much publicity as the Guardian Cap, though. Sales of the caps, which were introduced in 2012, took off after the company won the N.F.L.’s HeadHealthTECH Challenge in 2017 — two years after the league settled a lawsuit brought by more than 5,000 former players who accused the N.F.L. of hiding from them the dangers of concussions.

Guardian Sports received $20,000 from the league for additional testing, but the N.F.L.’s endorsement was priceless.

Orders for the caps from colleges, high schools and youth teams poured in. Nearly every college team in the top ranks practices with the caps. In 2021, researchers, including some affiliated with the N.F.L. and its players’ union, published a paper that said Guardian Caps reduced “head impact severity” by 9 percent.

That year, Guardian Sports introduced its NXT model, with an extra layer of padding for bigger, stronger players. The N.F.L. required linemen, tight ends and linebackers to wear them in training camp. In 2023, the mandate expanded to all contact practices, and running backs and fullbacks were added. Starting in 2024, wide receivers and defensive backs had to wear them in practices, and players could wear them in games. (...)

Researchers at Virginia Tech, which runs a well-regarded helmet-testing laboratory, found that players who wore the NXT version of the Guardian Cap experienced a 14 percent decline in rotational accelerations — basically, the turning of the head — and that their concussion risk was 34 percent lower than for players who wore only helmets.

The benefits were significantly lower for players who wore the XT, the model worn in youth leagues and high schools. Rotational acceleration was only 5 percent lower, and the concussion risk was reduced by 15 percent.

Stefan Duma, who leads the lab, said the smaller reductions, combined with better helmets and fewer full contact practices, suggested that the benefits of wearing the XT were negligible.

“We tested it thoroughly, and the benefits are just not there,” Dr. Duma said. “It’s all noise, no statistical difference in youth.”

Most parents and coaches, though, do not read research reports from testing labs, and there is little information on the Guardian Sports website that explains the difference in performance between the XT and NXT models. But looking at the testimonials on the website from Mr. Goodell and other N.F.L. luminaries, parents and coaches might believe they were buying the cap worn by the pros.

by Ken Belson, NY Times | Read more:

Images: Audra Melton, NYT; Cooper Neill/Getty

Images: Audra Melton, NYT; Cooper Neill/Getty

Wednesday, February 4, 2026

In Praise of Urban Disorder

In his essay “Planning for an Unplanned City,” Jason Thorne, Toronto’s chief planner, poses a pair of provocative questions to his colleagues. “Have our rules and regulations squeezed too much of the life out of our cities?” he asks. “But also how do you plan and design a city that is safe and functional while also leaving room for spontaneity and serendipity?”

This premise — that urban planning’s efforts to impose order risk editing out the culture, character, complexity and creative friction that makes cities cities — is a guiding theme in Messy Cities: Why We Can’t Plan Everything, a collection of essays, including Thorne’s, gathered by Toronto-based editors Zahra Ebrahim, Leslie Woo, Dylan Reid and John Lorinc. In it, they argue that “messiness is an essential element of the city.” Case studies from around the world show how imperfection can be embraced, created and preserved, from the informal street eateries of East Los Angeles to the sports facilities carved out of derelict spaces in Mumbai.

Embracing urban disorder might seem like an unlikely cause. But Woo, an urban planner and chief executive officer of the Toronto-based nonprofit CivicAction, and Reid, executive editor of Spacing magazine, offer up a series of questions that get at the heart of debates surrounding messy urbanism. In an essay about street art, they ask, “Is it ugly or creative? Does it bring disruption or diversity? Should it be left to emerge from below or be managed from above? Is it permanent or ephemeral? Does it benefit communities or just individuals? Does it create opportunity or discomfort? Are there limits around it and if so can they be effective?”

Bloomberg CityLab caught up with Woo and Ebrahim, cofounder of the public interest design studio Monumental, about why messiness in cities can be worth advocating for, and how to let the healthy kind flourish. The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You intentionally don’t give a specific definition for messy urbanism in the book, making the case that to do so would be antithetical to the idea itself. But if you were to give a general overview of the qualities and attributes you’d ascribe to messy cities, what would they be?

Leslie Woo: All of the authors included in the book brought to it some form of two things — wanting to have a sense of belonging in the places they live and trying to understand how they can have agency in their community. And what comes out of that are acts of defiance that manifest both as tiny and intimate experiences and as big gestures in cities.

Zahra Ebrahim: I think of it as where institutions end and people begin. It’s about agency. So much of the “messy” defiance is people trying to live within their cultures and identities in ways that cities don’t always create space for. We’re not trying to fetishize messiness, but we do want to acknowledge that when people feel that agency, cities become more vibrant, spontaneous and delightful.

LW: I think of the story urban planning professor Nina-Marie Lister, director of Toronto’s Ecological Design Lab, tells about fighting to keep her wild front yard habitat garden after being ordered to cut it down by the city. There was a bylaw in place intended by the municipality to control what it deemed “noxious vegetation” on private property. Lister ended up doing a public advocacy campaign to get the bylaw updated.

The phrase “messy cities” could be construed negatively but it seems like a real term of affection for the editors and authors of this book. What does it represent to you?

ZE: You can see it represented in the Bloordale neighborhood of Toronto. During lockdown in 2020, a group of local residents came together and turned a large, gravel-filled site of a demolished school into an unexpected shared space for social distancing. With handmade signage, they cheekily named the site “Bloordale Beach.” Over weeks, they and others in the community organically and spontaneously brought this imagined, landlocked beach to life, adding beach chairs, “swimming guidelines” around the puddle that had formed after a storm, even a “barkour” area for local dogs. It was both a “messy” community art project and third space, but also a place for residents to demonstrate their agency and find joy in an uncertain and difficult time.

LW: The thing that is delightful about this topic is many of these efforts are exercises in reimagining cities. Individuals and groups see a space and approach it in a different way with a spirit and ingenuity that we don’t see enough of. It’s an exercise in thinking about how we want to live. I also want to make the point that we aren’t advocating for more chaos and confusion but rather showing how these groups are attempting to make sense of where they live.

ZE: Messiness has become a wedge issue — a way to pronounce and lean into existing political cleavages. Across the world we see politicians pointing to the challenges cities face — housing affordability, transit accessibility, access to employment — and wrongfully blame or attribute these urban “messes” to specific populations and groups. We see this in the rising anti-immigrant rhetoric we hear all over the world. As an editing team, I think there was a shared understanding that multicultural and diverse societies are more successful and that when we have to navigate shared social and cultural space, it’s better for society.

This is also not all about the failure of institutions to serve the needs of the public. Some of this is about groups responding to failures of the present and shaping a better future. And some of what we’re talking about is people seeing opportunities to make the type of “mess” that would support their community to thrive, like putting a pop-up market and third space in a strip mall parking lot, and creating a space for people to come together.

You and the rest of the editors are based in Toronto and the city comes up recurrently in the book. What makes the city such an interesting case study in messy urbanism?

ZE: Toronto is what a local journalist, Doug Saunders, calls an “arrival city” — one in three newcomers in Canada land in Toronto. These waves of migration are encoded in our city’s DNA. I think of a place like Kensington Market, where there have been successive arrivals of immigrants each decade, from Jewish and Eastern European and Italian immigrants in the early 1900s to Caribbean and Chinese immigrants in the 1960s and ’70s.

Kensington continues to be one of the most vibrant urban spaces in the city. You’ve got the market, food vendors, shops and semi-informal commercial activity, cultural venues and jazz bars. In so many parts of Toronto you can’t see the history on the street but in Kensington you can see the palimpsest and layers of change it’s lived through. There is development pressure in every direction and major retailers opening nearby but it remains this vibrant representation of different eras of newcomers in Toronto and what they needed — socially, culturally and commercially. It’s a great example of where the formal and informal, the planned and unplanned meet. Every nook and cranny is filled with a story, with locals making a “mess,” but really just expressing their agency.

LW: This messy urbanism can also be seen in Toronto’s apartment tower communities that were built in the 1960s. These buildings have experienced periods of neglect and changes in ownership. But today when moving from floor to floor, it feels like traveling around the entire world; you can move from the Caribbean to continental Africa to the Middle East. These are aerial cities in and of themselves. They’re a great example of people taking a place where the conditions aren’t ideal and telling their own different story — it’s everything from the music to the food to the languages.

You didn’t include any case studies or essays from Europe in the book. Why did you make that choice, and what does an overreliance on looking to cities like Copenhagen do to the way we think of and plan for cities?

LW: When I trained as an urban planner and architect, all the pedagogy was very Eurocentric — it was Spain, France and Greece. But if we want to reframe how we think about cities, we need to reframe our points of reference.

ZE: During our editorial meetings we talked about how the commonly accepted ideas about urban order that we know are Eurocentric by design, and don’t represent the multitude of people that live in cities and what “order” may mean to them. Again, it’s not to celebrate chaos but rather to say there are different mental models of what orderliness and messiness can look like.

Go to a place like Delhi and look at the way traffic roundabouts function. There are pedestrians and cars and everybody is moving in the direction they need to move in, it’s like a river of mobility. If you’re sitting in the back of a taxi coming from North America, it looks like chaos, but to the people that live there it’s just how the city moves.

In a chapter about Mexico City’s apartment architecture, Daniel Gordon talks about what it can teach us about how to create interesting streets and neighborhoods by becoming less attached to overly prescriptive planning and instead embracing a mix of ground-floor uses and buildings with varying materials and color palettes, setbacks and heights. He argues that design guidelines can negate creativity and expression in the built environment.

In another chapter, urban geography professor Andre Sorensen talks about Tokyo, which despite being perceived as a spontaneously messy city actually operates under one of the strictest zoning systems in the world. Built forms are highly regulated, but land use mix and subdivision controls aren’t. It’s yet another example of how different urban cultures and regulatory systems work to different sets of values and conceptions of order and disorder. We tried to pay closer attention to case studies that expanded the aperture of what North American urbanism typically covers.

by Rebecca Greenwald, Bloomberg | Read more:

Image:Alfredo Martinez/Getty Images

This premise — that urban planning’s efforts to impose order risk editing out the culture, character, complexity and creative friction that makes cities cities — is a guiding theme in Messy Cities: Why We Can’t Plan Everything, a collection of essays, including Thorne’s, gathered by Toronto-based editors Zahra Ebrahim, Leslie Woo, Dylan Reid and John Lorinc. In it, they argue that “messiness is an essential element of the city.” Case studies from around the world show how imperfection can be embraced, created and preserved, from the informal street eateries of East Los Angeles to the sports facilities carved out of derelict spaces in Mumbai.

Embracing urban disorder might seem like an unlikely cause. But Woo, an urban planner and chief executive officer of the Toronto-based nonprofit CivicAction, and Reid, executive editor of Spacing magazine, offer up a series of questions that get at the heart of debates surrounding messy urbanism. In an essay about street art, they ask, “Is it ugly or creative? Does it bring disruption or diversity? Should it be left to emerge from below or be managed from above? Is it permanent or ephemeral? Does it benefit communities or just individuals? Does it create opportunity or discomfort? Are there limits around it and if so can they be effective?”

Bloomberg CityLab caught up with Woo and Ebrahim, cofounder of the public interest design studio Monumental, about why messiness in cities can be worth advocating for, and how to let the healthy kind flourish. The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You intentionally don’t give a specific definition for messy urbanism in the book, making the case that to do so would be antithetical to the idea itself. But if you were to give a general overview of the qualities and attributes you’d ascribe to messy cities, what would they be?

Leslie Woo: All of the authors included in the book brought to it some form of two things — wanting to have a sense of belonging in the places they live and trying to understand how they can have agency in their community. And what comes out of that are acts of defiance that manifest both as tiny and intimate experiences and as big gestures in cities.

Zahra Ebrahim: I think of it as where institutions end and people begin. It’s about agency. So much of the “messy” defiance is people trying to live within their cultures and identities in ways that cities don’t always create space for. We’re not trying to fetishize messiness, but we do want to acknowledge that when people feel that agency, cities become more vibrant, spontaneous and delightful.

LW: I think of the story urban planning professor Nina-Marie Lister, director of Toronto’s Ecological Design Lab, tells about fighting to keep her wild front yard habitat garden after being ordered to cut it down by the city. There was a bylaw in place intended by the municipality to control what it deemed “noxious vegetation” on private property. Lister ended up doing a public advocacy campaign to get the bylaw updated.

The phrase “messy cities” could be construed negatively but it seems like a real term of affection for the editors and authors of this book. What does it represent to you?

ZE: You can see it represented in the Bloordale neighborhood of Toronto. During lockdown in 2020, a group of local residents came together and turned a large, gravel-filled site of a demolished school into an unexpected shared space for social distancing. With handmade signage, they cheekily named the site “Bloordale Beach.” Over weeks, they and others in the community organically and spontaneously brought this imagined, landlocked beach to life, adding beach chairs, “swimming guidelines” around the puddle that had formed after a storm, even a “barkour” area for local dogs. It was both a “messy” community art project and third space, but also a place for residents to demonstrate their agency and find joy in an uncertain and difficult time.

LW: The thing that is delightful about this topic is many of these efforts are exercises in reimagining cities. Individuals and groups see a space and approach it in a different way with a spirit and ingenuity that we don’t see enough of. It’s an exercise in thinking about how we want to live. I also want to make the point that we aren’t advocating for more chaos and confusion but rather showing how these groups are attempting to make sense of where they live.

ZE: Messiness has become a wedge issue — a way to pronounce and lean into existing political cleavages. Across the world we see politicians pointing to the challenges cities face — housing affordability, transit accessibility, access to employment — and wrongfully blame or attribute these urban “messes” to specific populations and groups. We see this in the rising anti-immigrant rhetoric we hear all over the world. As an editing team, I think there was a shared understanding that multicultural and diverse societies are more successful and that when we have to navigate shared social and cultural space, it’s better for society.

This is also not all about the failure of institutions to serve the needs of the public. Some of this is about groups responding to failures of the present and shaping a better future. And some of what we’re talking about is people seeing opportunities to make the type of “mess” that would support their community to thrive, like putting a pop-up market and third space in a strip mall parking lot, and creating a space for people to come together.

You and the rest of the editors are based in Toronto and the city comes up recurrently in the book. What makes the city such an interesting case study in messy urbanism?

ZE: Toronto is what a local journalist, Doug Saunders, calls an “arrival city” — one in three newcomers in Canada land in Toronto. These waves of migration are encoded in our city’s DNA. I think of a place like Kensington Market, where there have been successive arrivals of immigrants each decade, from Jewish and Eastern European and Italian immigrants in the early 1900s to Caribbean and Chinese immigrants in the 1960s and ’70s.

Kensington continues to be one of the most vibrant urban spaces in the city. You’ve got the market, food vendors, shops and semi-informal commercial activity, cultural venues and jazz bars. In so many parts of Toronto you can’t see the history on the street but in Kensington you can see the palimpsest and layers of change it’s lived through. There is development pressure in every direction and major retailers opening nearby but it remains this vibrant representation of different eras of newcomers in Toronto and what they needed — socially, culturally and commercially. It’s a great example of where the formal and informal, the planned and unplanned meet. Every nook and cranny is filled with a story, with locals making a “mess,” but really just expressing their agency.

LW: This messy urbanism can also be seen in Toronto’s apartment tower communities that were built in the 1960s. These buildings have experienced periods of neglect and changes in ownership. But today when moving from floor to floor, it feels like traveling around the entire world; you can move from the Caribbean to continental Africa to the Middle East. These are aerial cities in and of themselves. They’re a great example of people taking a place where the conditions aren’t ideal and telling their own different story — it’s everything from the music to the food to the languages.

You didn’t include any case studies or essays from Europe in the book. Why did you make that choice, and what does an overreliance on looking to cities like Copenhagen do to the way we think of and plan for cities?

LW: When I trained as an urban planner and architect, all the pedagogy was very Eurocentric — it was Spain, France and Greece. But if we want to reframe how we think about cities, we need to reframe our points of reference.

ZE: During our editorial meetings we talked about how the commonly accepted ideas about urban order that we know are Eurocentric by design, and don’t represent the multitude of people that live in cities and what “order” may mean to them. Again, it’s not to celebrate chaos but rather to say there are different mental models of what orderliness and messiness can look like.

Go to a place like Delhi and look at the way traffic roundabouts function. There are pedestrians and cars and everybody is moving in the direction they need to move in, it’s like a river of mobility. If you’re sitting in the back of a taxi coming from North America, it looks like chaos, but to the people that live there it’s just how the city moves.

In a chapter about Mexico City’s apartment architecture, Daniel Gordon talks about what it can teach us about how to create interesting streets and neighborhoods by becoming less attached to overly prescriptive planning and instead embracing a mix of ground-floor uses and buildings with varying materials and color palettes, setbacks and heights. He argues that design guidelines can negate creativity and expression in the built environment.

In another chapter, urban geography professor Andre Sorensen talks about Tokyo, which despite being perceived as a spontaneously messy city actually operates under one of the strictest zoning systems in the world. Built forms are highly regulated, but land use mix and subdivision controls aren’t. It’s yet another example of how different urban cultures and regulatory systems work to different sets of values and conceptions of order and disorder. We tried to pay closer attention to case studies that expanded the aperture of what North American urbanism typically covers.

by Rebecca Greenwald, Bloomberg | Read more:

Image:Alfredo Martinez/Getty Images

[ed. Give me a messy city any day, or at least one with a few messy parts.]

Claude's New Constitution

We're publishing a new constitution for our AI model, Claude. It's a detailed description of Anthropic's vision for Claude's values and behavior; a holistic document that explains the context in which Claude operates and the kind of entity we would like Claude to be.

The constitution is a crucial part of our model training process, and its content directly shapes Claude's behavior. Training models is a difficult task, and Claude's outputs might not always adhere to the constitution's ideals. But we think that the way the new constitution is written—with a thorough explanation of our intentions and the reasons behind them—makes it more likely to cultivate good values during training.

In this post, we describe what we've included in the new constitution and some of the considerations that informed our approach.

We're releasing Claude's constitution in full under a Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Deed, meaning it can be freely used by anyone for any purpose without asking for permission.

What is Claude's Constitution?

Claude's constitution is the foundational document that both expresses and shapes who Claude is. It contains detailed explanations of the values we would like Claude to embody and the reasons why. In it, we explain what we think it means for Claude to be helpful while remaining broadly safe, ethical, and compliant with our guidelines. The constitution gives Claude information about its situation and offers advice for how to deal with difficult situations and tradeoffs, like balancing honesty with compassion and the protection of sensitive information. Although it might sound surprising, the constitution is written primarily for Claude. It is intended to give Claude the knowledge and understanding it needs to act well in the world.

We treat the constitution as the final authority on how we want Claude to be and to behave—that is, any other training or instruction given to Claude should be consistent with both its letter and its underlying spirit. This makes publishing the constitution particularly important from a transparency perspective: it lets people understand which of Claude's behaviors are intended versus unintended, to make informed choices, and to provide useful feedback. We think transparency of this kind will become ever more important as AIs start to exert more influence in society.

We use the constitution at various stages of the training process. This has grown out of training techniques we've been using since 2023, when we first began training Claude models using Constitutional AI. Our approach has evolved significantly since then, and the new constitution plays an even more central role in training.

Claude itself also uses the constitution to construct many kinds of synthetic training data, including data that helps it learn and understand the constitution, conversations where the constitution might be relevant, responses that are in line with its values, and rankings of possible responses. All of these can be used to train future versions of Claude to become the kind of entity the constitution describes. This practical function has shaped how we've written the constitution: it needs to work both as a statement of abstract ideals and a useful artifact for training.

Our new approach to Claude's Constitution

Our previous Constitution was composed of a list of standalone principles. We've come to believe that a different approach is necessary. We think that in order to be good actors in the world, AI models like Claude need to understand why we want them to behave in certain ways, and we need to explain this to them rather than merely specify what we want them to do. If we want models to exercise good judgment across a wide range of novel situations, they need to be able to generalize—to apply broad principles rather than mechanically following specific rules.

Specific rules and bright lines sometimes have their advantages. They can make models' actions more predictable, transparent, and testable, and we do use them for some especially high-stakes behaviors in which Claude should never engage (we call these "hard constraints"). But such rules can also be applied poorly in unanticipated situations or when followed too rigidly . We don't intend for the constitution to be a rigid legal document—and legal constitutions aren't necessarily like this anyway.

The constitution reflects our current thinking about how to approach a dauntingly novel and high-stakes project: creating safe, beneficial non-human entities whose capabilities may come to rival or exceed our own. Although the document is no doubt flawed in many ways, we want it to be something future models can look back on and see as an honest and sincere attempt to help Claude understand its situation, our motives, and the reasons we shape Claude in the ways we do.

A brief summary of the new constitution

In order to be both safe and beneficial, we want all current Claude models to be:

Most of the constitution is focused on giving more detailed explanations and guidance about these priorities. The main sections are as follows:

by Zac Hatfield-Dodds, Drake Thomas, Anthropic | Read more:

The constitution is a crucial part of our model training process, and its content directly shapes Claude's behavior. Training models is a difficult task, and Claude's outputs might not always adhere to the constitution's ideals. But we think that the way the new constitution is written—with a thorough explanation of our intentions and the reasons behind them—makes it more likely to cultivate good values during training.

In this post, we describe what we've included in the new constitution and some of the considerations that informed our approach.

We're releasing Claude's constitution in full under a Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Deed, meaning it can be freely used by anyone for any purpose without asking for permission.

What is Claude's Constitution?

Claude's constitution is the foundational document that both expresses and shapes who Claude is. It contains detailed explanations of the values we would like Claude to embody and the reasons why. In it, we explain what we think it means for Claude to be helpful while remaining broadly safe, ethical, and compliant with our guidelines. The constitution gives Claude information about its situation and offers advice for how to deal with difficult situations and tradeoffs, like balancing honesty with compassion and the protection of sensitive information. Although it might sound surprising, the constitution is written primarily for Claude. It is intended to give Claude the knowledge and understanding it needs to act well in the world.

We treat the constitution as the final authority on how we want Claude to be and to behave—that is, any other training or instruction given to Claude should be consistent with both its letter and its underlying spirit. This makes publishing the constitution particularly important from a transparency perspective: it lets people understand which of Claude's behaviors are intended versus unintended, to make informed choices, and to provide useful feedback. We think transparency of this kind will become ever more important as AIs start to exert more influence in society.

We use the constitution at various stages of the training process. This has grown out of training techniques we've been using since 2023, when we first began training Claude models using Constitutional AI. Our approach has evolved significantly since then, and the new constitution plays an even more central role in training.

Claude itself also uses the constitution to construct many kinds of synthetic training data, including data that helps it learn and understand the constitution, conversations where the constitution might be relevant, responses that are in line with its values, and rankings of possible responses. All of these can be used to train future versions of Claude to become the kind of entity the constitution describes. This practical function has shaped how we've written the constitution: it needs to work both as a statement of abstract ideals and a useful artifact for training.

Our new approach to Claude's Constitution

Our previous Constitution was composed of a list of standalone principles. We've come to believe that a different approach is necessary. We think that in order to be good actors in the world, AI models like Claude need to understand why we want them to behave in certain ways, and we need to explain this to them rather than merely specify what we want them to do. If we want models to exercise good judgment across a wide range of novel situations, they need to be able to generalize—to apply broad principles rather than mechanically following specific rules.

Specific rules and bright lines sometimes have their advantages. They can make models' actions more predictable, transparent, and testable, and we do use them for some especially high-stakes behaviors in which Claude should never engage (we call these "hard constraints"). But such rules can also be applied poorly in unanticipated situations or when followed too rigidly . We don't intend for the constitution to be a rigid legal document—and legal constitutions aren't necessarily like this anyway.

The constitution reflects our current thinking about how to approach a dauntingly novel and high-stakes project: creating safe, beneficial non-human entities whose capabilities may come to rival or exceed our own. Although the document is no doubt flawed in many ways, we want it to be something future models can look back on and see as an honest and sincere attempt to help Claude understand its situation, our motives, and the reasons we shape Claude in the ways we do.

A brief summary of the new constitution

In order to be both safe and beneficial, we want all current Claude models to be:

- Broadly safe: not undermining appropriate human mechanisms to oversee AI during the current phase of development;

- Broadly ethical: being honest, acting according to good values, and avoiding actions that are inappropriate, dangerous, or harmful;

- Compliant with Anthropic's guidelines: acting in accordance with more specific guidelines from Anthropic where relevant;

- Genuinely helpful: benefiting the operators and users they interact with.

Most of the constitution is focused on giving more detailed explanations and guidance about these priorities. The main sections are as follows:

by Zac Hatfield-Dodds, Drake Thomas, Anthropic | Read more:

[ed. Much respect for Anthropic who seem to be doing more for AI safety than anyone else in the industry. Hopefully, others will follow and refine this groundbreaking effort.

Labels:

Critical Thought,

Design,

Education,

Philosophy,

Psychology,

Relationships,

Technology

Tuesday, January 20, 2026

It's Not Normal

Samantha: This town has a weird smell that you're all probably used to…but I'm not.

Mrs Krabappel: It'll take you about six weeks, dear.-The Simpsons, "Bart's Friend Falls in Love," S3E23, May 7, 1992

We are living through weird times, and they've persisted for so long that you probably don't even notice it. But these times are not normal.

Now, I realize that this covers a lot of ground, and without detracting from all the other ways in which the world is weird and bad, I want to focus on one specific and pervasive and awful way in which this world is not normal, in part because this abnormality has a defined cause, a precise start date, and an obvious, actionable remedy.

6 years, 5 months and 22 days after Fox aired "Bart's Friend Falls in Love," Bill Clinton signed a new bill into law: the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA).

Under Section 1201 of the DMCA, it's a felony to modify your own property in ways that the manufacturer disapproves of, even if your modifications accomplish some totally innocuous, legal, and socially beneficial goal. Not a little felony, either: DMCA 1201 provides for a five year sentence and a $500,000 fine for a first offense.

Back when the DMCA was being debated, its proponents insisted that their critics were overreacting. They pointed to the legal barriers to invoking DMCA 1201, and insisted that these new restrictions would only apply to a few marginal products in narrow ways that the average person would never even notice.

But that was obvious nonsense, obvious even in 1998, and far more obvious today, more than a quarter-century on. In order for a manufacturer to criminalize modifications to your own property, they have to satisfy two criteria: first, they must sell you a device with a computer in it; and second, they must design that computer with an "access control" that you have to work around in order to make a modification.

For example, say your toaster requires that you scan your bread before it will toast it, to make sure that you're only using a special, expensive kind of bread that kicks back a royalty to the manufacturer. If the embedded computer that does the scanning ships from the factory with a program that is supposed to prevent you from turning off the scanning step, then it is a felony to modify your toaster to work with "unauthorized bread":

If this sounds outlandish, then a) You definitely didn't walk the floor at CES last week, where there were a zillion "cooking robots" that required proprietary feedstock; and b) You haven't really thought hard about your iPhone (which will not allow you to install software of your choosing):

But back in 1998, computers – even the kind of low-powered computers that you'd embed in an appliance – were expensive and relatively rare. No longer! Today, manufacturers source powerful "System on a Chip" (SoC) processors at prices ranging from $0.25 to $8. These are full-fledged computers, easily capable of running an "access control" that satisfies DMCA 1201.

Likewise, in 1998, "access controls" (also called "DRM," "technical protection measures," etc) were a rarity in the field. That was because computer scientists broadly viewed these measures as useless. A determined adversary could always find a way around an access control, and they could package up that break as a software tool and costlessly, instantaneously distribute it over the internet to everyone in the world who wanted to do something that an access control impeded. Access controls were a stupid waste of engineering resources and a source of needless complexity and brittleness:

But – as critics pointed out in 1998 – chips were obviously going to get much cheaper, and if the US Congress made it a felony to bypass an access control, then every kind of manufacturer would be tempted to add some cheap SoCs to their products so they could add access controls and thereby felonize any uses of their products that cut into their profits. Basically, the DMCA offered manufacturers a bargain: add a dollar or two to the bill of materials for your product, and in return, the US government will imprison any competitors who offer your customers a "complementary good" that improves on it.

It's even worse than this: another thing that was obvious in 1998 was that once a manufacturer added a chip to a device, they would probably also figure out a way to connect it to the internet. Once that device is connected to the internet, the manufacturer can push software updates to it at will, which will be installed without user intervention. What's more, by using an access control in connection with that over-the-air update mechanism, the manufacturer can make it a felony to block its updates.

Which means that a manufacturer can sell you a device and then mandatorily update it at a later date to take away its functionality, and then sell that functionality back to you as a "subscription":

A thing that keeps happening:

And happening:

And happening:

In fact, it happens so often I've coined a term for it, "The Darth Vader MBA" (as in, "I'm altering the deal. Pray I don't alter it any further"):

Here's what this all means: any manufacturer who devotes a small amount of engineering work and incurs a small hardware expense can extinguish private property rights altogether.

What do I mean by private property? Well, we can look to Blackstone's 1753 treatise:

It's not just iPhones: versions of this play out in your medical implants (hearing aid, insulin pump, etc); appliances (stoves, fridges, washing machines); cars and ebikes; set-top boxes and game consoles; ebooks and streaming videos; small appliances (toothbrushes, TVs, speakers), and more.

Increasingly, things that you actually own are the exception, not the rule.

And this is not normal. The end of ownership represents an overturn of a foundation of modern civilization. The fact that the only "people" who can truly own something are the transhuman, immortal colony organisms we call "Limited Liability Corporations" is an absolutely surreal reversal of the normal order of things.

It's a reversal with deep implications: for one thing, it means that you can't protect yourself from raids on your private data or ready cash by adding privacy blockers to your device, which would make it impossible for airlines or ecommerce sites to guess about how rich/desperate you are before quoting you a "personalized price":

It also means you can't stop your device from leaking information about your movements, or even your conversations – Microsoft has announced that it will gather all of your private communications and ship them to its servers for use by "agentic AI": (...)

Microsoft has also confirmed that it provides US authorities with warrantless, secret access to your data:

This is deeply abnormal. Sure, greedy corporate control freaks weren't invented in the 21st century, but the laws that let those sociopaths put you in prison for failing to arrange your affairs to their benefit – and your own detriment – are.

But because computers got faster and cheaper over decades, the end of ownership has had an incremental rollout, and we've barely noticed that it's happened. Sure, we get irritated when our garage-door opener suddenly requires us to look at seven ads every time we use the app that makes it open or close:

But societally, we haven't connected that incident to this wider phenomenon. It stinks here, but we're all used to it.

It's not normal to buy a book and then not be able to lend it, sell it, or give it away. Lending, selling and giving away books is older than copyright. It's older than publishing. It's older than printing. It's older than paper. It is fucking weird (and also terrible) (obviously) that there's a new kind of very popular book that you can go to prison for lending, selling or giving away.

We're just a few cycles away from a pair of shoes that can figure out which shoelaces you're using, or a dishwasher that can block you from using third-party dishes:

It's not normal, and it has profound implications for our security, our privacy, and our society. It makes us easy pickings for corporate vampires who drain our wallets through the gadgets and tools we rely on. It makes us easy pickings for fascists and authoritarians who ally themselves with corporate vampires by promising them tax breaks in exchange for collusion in the destruction of a free society.

I know that these problems are more important than whether or not we think this is normal. But still. It. Is. Just. Not. Normal.

[ed. Anything labeled 'smart' is usually suspect. What's particularly dangerous is if successive generations fall prey to what conservation biology calls shifting baseline syndrome (forgetting or never really missing something that's been lost, so we don't grieve or fight to restore it). For a deep dive into why everything keeps getting worse see Mr. Doctorow's new book: Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It," Farrar, Straus, Giroux, October 7 2025.]

Now, I realize that this covers a lot of ground, and without detracting from all the other ways in which the world is weird and bad, I want to focus on one specific and pervasive and awful way in which this world is not normal, in part because this abnormality has a defined cause, a precise start date, and an obvious, actionable remedy.

6 years, 5 months and 22 days after Fox aired "Bart's Friend Falls in Love," Bill Clinton signed a new bill into law: the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA).

Under Section 1201 of the DMCA, it's a felony to modify your own property in ways that the manufacturer disapproves of, even if your modifications accomplish some totally innocuous, legal, and socially beneficial goal. Not a little felony, either: DMCA 1201 provides for a five year sentence and a $500,000 fine for a first offense.

Back when the DMCA was being debated, its proponents insisted that their critics were overreacting. They pointed to the legal barriers to invoking DMCA 1201, and insisted that these new restrictions would only apply to a few marginal products in narrow ways that the average person would never even notice.

But that was obvious nonsense, obvious even in 1998, and far more obvious today, more than a quarter-century on. In order for a manufacturer to criminalize modifications to your own property, they have to satisfy two criteria: first, they must sell you a device with a computer in it; and second, they must design that computer with an "access control" that you have to work around in order to make a modification.

For example, say your toaster requires that you scan your bread before it will toast it, to make sure that you're only using a special, expensive kind of bread that kicks back a royalty to the manufacturer. If the embedded computer that does the scanning ships from the factory with a program that is supposed to prevent you from turning off the scanning step, then it is a felony to modify your toaster to work with "unauthorized bread":

If this sounds outlandish, then a) You definitely didn't walk the floor at CES last week, where there were a zillion "cooking robots" that required proprietary feedstock; and b) You haven't really thought hard about your iPhone (which will not allow you to install software of your choosing):

But back in 1998, computers – even the kind of low-powered computers that you'd embed in an appliance – were expensive and relatively rare. No longer! Today, manufacturers source powerful "System on a Chip" (SoC) processors at prices ranging from $0.25 to $8. These are full-fledged computers, easily capable of running an "access control" that satisfies DMCA 1201.

Likewise, in 1998, "access controls" (also called "DRM," "technical protection measures," etc) were a rarity in the field. That was because computer scientists broadly viewed these measures as useless. A determined adversary could always find a way around an access control, and they could package up that break as a software tool and costlessly, instantaneously distribute it over the internet to everyone in the world who wanted to do something that an access control impeded. Access controls were a stupid waste of engineering resources and a source of needless complexity and brittleness:

But – as critics pointed out in 1998 – chips were obviously going to get much cheaper, and if the US Congress made it a felony to bypass an access control, then every kind of manufacturer would be tempted to add some cheap SoCs to their products so they could add access controls and thereby felonize any uses of their products that cut into their profits. Basically, the DMCA offered manufacturers a bargain: add a dollar or two to the bill of materials for your product, and in return, the US government will imprison any competitors who offer your customers a "complementary good" that improves on it.

It's even worse than this: another thing that was obvious in 1998 was that once a manufacturer added a chip to a device, they would probably also figure out a way to connect it to the internet. Once that device is connected to the internet, the manufacturer can push software updates to it at will, which will be installed without user intervention. What's more, by using an access control in connection with that over-the-air update mechanism, the manufacturer can make it a felony to block its updates.

Which means that a manufacturer can sell you a device and then mandatorily update it at a later date to take away its functionality, and then sell that functionality back to you as a "subscription":

A thing that keeps happening:

And happening:

And happening:

In fact, it happens so often I've coined a term for it, "The Darth Vader MBA" (as in, "I'm altering the deal. Pray I don't alter it any further"):

Here's what this all means: any manufacturer who devotes a small amount of engineering work and incurs a small hardware expense can extinguish private property rights altogether.

What do I mean by private property? Well, we can look to Blackstone's 1753 treatise:

The right of property; or that sole and despotic dominion which one man claims and exercises over the external things of the world, in total exclusion of the right of any other individual in the universe.You can't own your iPhone. If you take your iPhone to Apple and they tell you that it is beyond repair, you have to throw it away. If the repair your phone needs involves "parts pairing" (where a new part won't be recognized until an Apple technician "initializes" it through a DMCA-protected access control), then it's a felony to get that phone fixed somewhere else. If Apple tells you your phone is no longer supported because they've updated their OS, then it's a felony to wipe the phone and put a different OS on it (because installing a new OS involves bypassing an "access control" in the phone's bootloader). If Apple tells you that you can't have a piece of software – like ICE Block, an app that warns you if there are nearby ICE killers who might shoot you in the head through your windshield, which Apple has barred from its App Store on the grounds that ICE is a "protected class" – then you can't install it, because installing software that isn't delivered via the App Store involves bypassing an "access control" that checks software to ensure that it's authorized (just like the toaster with its unauthorized bread).

It's not just iPhones: versions of this play out in your medical implants (hearing aid, insulin pump, etc); appliances (stoves, fridges, washing machines); cars and ebikes; set-top boxes and game consoles; ebooks and streaming videos; small appliances (toothbrushes, TVs, speakers), and more.

Increasingly, things that you actually own are the exception, not the rule.

And this is not normal. The end of ownership represents an overturn of a foundation of modern civilization. The fact that the only "people" who can truly own something are the transhuman, immortal colony organisms we call "Limited Liability Corporations" is an absolutely surreal reversal of the normal order of things.

It's a reversal with deep implications: for one thing, it means that you can't protect yourself from raids on your private data or ready cash by adding privacy blockers to your device, which would make it impossible for airlines or ecommerce sites to guess about how rich/desperate you are before quoting you a "personalized price":

It also means you can't stop your device from leaking information about your movements, or even your conversations – Microsoft has announced that it will gather all of your private communications and ship them to its servers for use by "agentic AI": (...)

Microsoft has also confirmed that it provides US authorities with warrantless, secret access to your data:

This is deeply abnormal. Sure, greedy corporate control freaks weren't invented in the 21st century, but the laws that let those sociopaths put you in prison for failing to arrange your affairs to their benefit – and your own detriment – are.

But because computers got faster and cheaper over decades, the end of ownership has had an incremental rollout, and we've barely noticed that it's happened. Sure, we get irritated when our garage-door opener suddenly requires us to look at seven ads every time we use the app that makes it open or close:

But societally, we haven't connected that incident to this wider phenomenon. It stinks here, but we're all used to it.

It's not normal to buy a book and then not be able to lend it, sell it, or give it away. Lending, selling and giving away books is older than copyright. It's older than publishing. It's older than printing. It's older than paper. It is fucking weird (and also terrible) (obviously) that there's a new kind of very popular book that you can go to prison for lending, selling or giving away.

We're just a few cycles away from a pair of shoes that can figure out which shoelaces you're using, or a dishwasher that can block you from using third-party dishes:

It's not normal, and it has profound implications for our security, our privacy, and our society. It makes us easy pickings for corporate vampires who drain our wallets through the gadgets and tools we rely on. It makes us easy pickings for fascists and authoritarians who ally themselves with corporate vampires by promising them tax breaks in exchange for collusion in the destruction of a free society.

I know that these problems are more important than whether or not we think this is normal. But still. It. Is. Just. Not. Normal.

by Cory Doctorow, Pluralistic | Read more:

Image: uncredited

Labels:

Business,

Copyright,

Crime,

Culture,

Design,

Economics,

Government,

Law,

Literature,

Media,

Politics,

Security,

Technology

Sunday, January 18, 2026

The Monkey’s Paw Curls

[ed. More than anyone probably wants to know (or can understand) about prediction markets.]

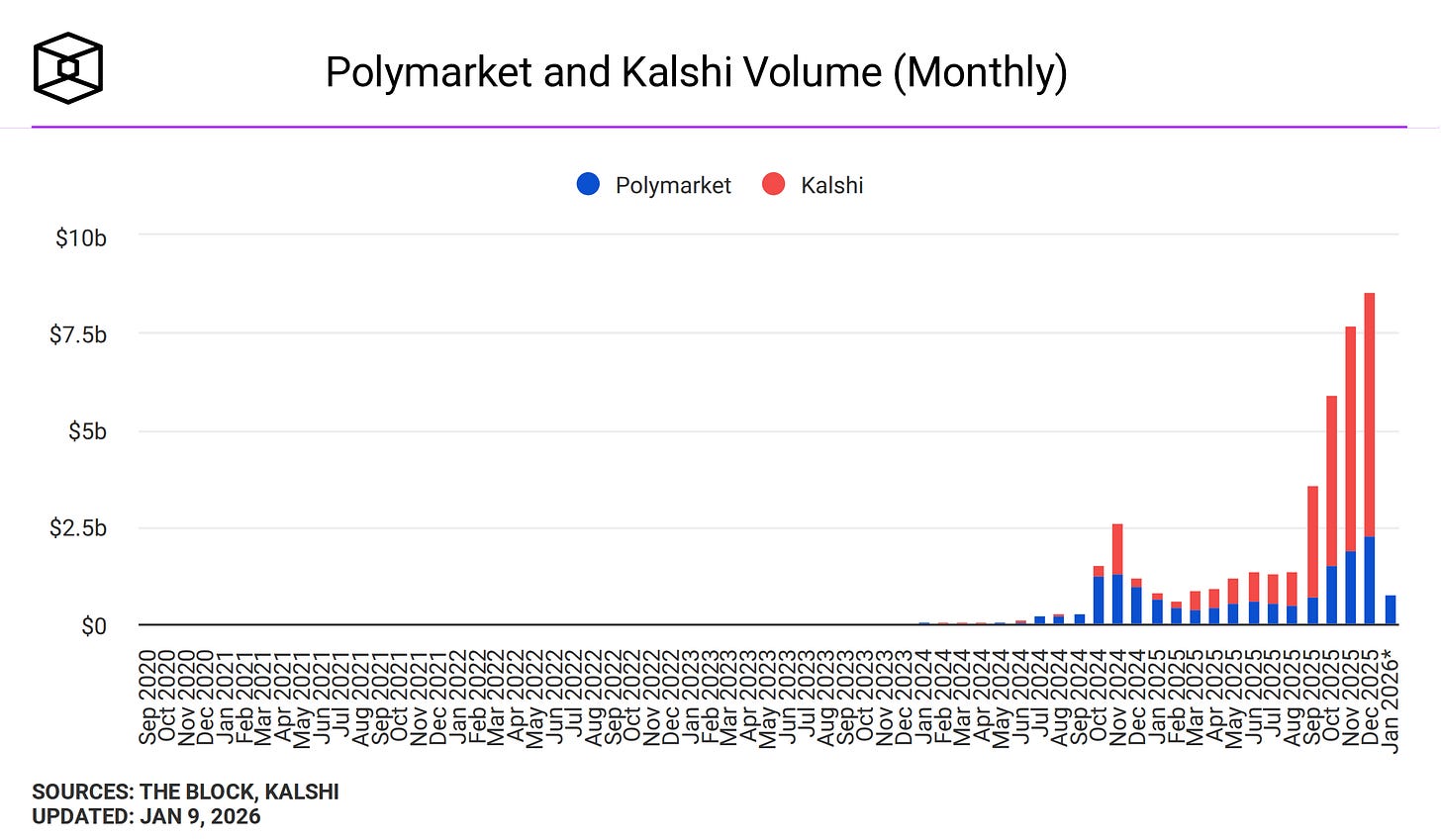

Since we last spoke, prediction markets have gone to the moon, rising from millions to billions in monthly volume.

For a few weeks in October, Polymarket founder Shayne Coplan was the world’s youngest self-made billionaire (now it’s some AI people). Kalshi is so accurate that it’s getting called a national security threat.

The catch is, of course, that it’s mostly degenerate gambling, especially sports betting. Kalshi is 81% sports by monthly volume. Polymarket does better - only 37% - but some of the remainder is things like this $686,000 market on how often Elon Musk will tweet this week - currently dominated by the “140 - 164 times” category.

(ironically, this seems to be a regulatory difference - US regulators don’t mind sports betting, but look unfavorably on potentially “insensitive” markets like bets about wars. Polymarket has historically been offshore, and so able to concentrate on geopolitics; Kalshi has been in the US, and so stuck mostly to sports. But Polymarket is in the process of moving onshore; I don’t know if this will affect their ability to offer geopolitical markets)

Degenerate gambling is bad. Insofar as prediction markets have acted as a Trojan Horse to enable it, this is bad. Insofar as my advocacy helped make this possible, I am bad. I can only plead that it didn’t really seem plausible, back in 2021, that a presidential administration would keep all normal restrictions on sports gambling but also let prediction markets do it as much as they wanted. If only there had been some kind of decentralized forecasting tool that could have given me a canonical probability on this outcome!

Still, it might seem that, whatever the degenerate gamblers are doing, we at least have some interesting data. There are now strong, minimally-regulated, high-volume prediction markets on important global events. In this column, I previously claimed this would revolutionize society. Has it?

I don’t feel revolutionized. Why not?

The problem isn’t that the prediction markets are bad. There’s been a lot of noise about insider trading and disputed resolutions. But insider trading should only increase accuracy - it’s bad for traders, but good for information-seekers - and my impression is that the disputed resolutions were handled as well as possible. When I say I don’t feel revolutionized, it’s not because I don’t believe it when it says there’s a 20% chance Khameini will be out before the end of the month. The several thousand people who have invested $6 million in that question have probably converged upon the most accurate probability possible with existing knowledge, just the way prediction markets should.

I actually like this. Everyone is talking about the protests in Iran, and it’s hard to gauge their importance, and knowing that there’s a 20% chance Khameini is removed by February really does help to place them in context. The missing link seems to be between “it’s now possible to place global events in probabilistic context → society revolutionized”.

Here are some possibilities:

Maybe people just haven’t caught on yet? Most news sources still don’t cite prediction markets, even when many people would care about their outcome. For example, the Khameini market hasn’t gotten mentioned in articles about the Iran protests, even though “will these protests succeed in toppling the regime?” is the obvious first question any reader would ask.

Maybe the problem is that probabilities don’t matter? Maybe there’s some State Department official who would change plans slightly over a 20% vs. 40% chance of Khameini departure, or an Iranian official for whom that would mean the difference between loyalty and defection, and these people are benefiting slightly, but not enough that society feels revolutionized.

Maybe society has been low-key revolutionized and we haven’t noticed? Very optimistically, maybe there aren’t as many “obviously the protests will work, only a defeatist doomer traitor would say they have any chance of failing!” “no, obviously the protests will fail, you’re a neoliberal shill if you think they could work” takes as there used to be. Maybe everyone has converged to a unified assessment of probabilistic knowledge, and we’re all better off as a result.

Maybe Polymarket and Kalshi don’t have the right questions. Ask yourself: what are the big future-prediction questions that important disagreements pivot around? When I try this exercise, I get things like:

- Will the AI bubble pop? Will scaling get us all the way to AGI? Will AI be misaligned?

- Will Trump turn America into a dictatorship? Make it great again? Somewhere in between?

- Will YIMBY policies lower rents? How much?

- Will selling US chips to China help them win the AI race?

- Will kidnapping Venezuela’s president weaken international law in some meaningful way that will cause trouble in the future?

- If America nation-builds Venezuela, for whatever definition of nation-build, will that work well, or backfire?

Annals of The Rulescucks

The new era of prediction markets has provided charming additions to the language, including “rulescuck” - someone who loses an otherwise-prescient bet based on technicalities of the resolution criteria.

Resolution criteria are the small print explaining what counts as the prediction market topic “happening'“. For example, in the Khameini example above, Khameini qualifies as being “out of power” if:

…he resigns, is detained, or otherwise loses his position or is prevented from fulfilling his duties as Supreme Leader of Iran within this market's timeframe. The primary resolution source for this market will be a consensus of credible reporting.You can imagine ways this definition departs from an exact common-sensical concept of “out of power” - for example, if Khameini gets stuck in an elevator for half an hour and misses a key meeting, does this count as him being “prevented from fulfilling his duties”? With thousands of markets getting resolved per month, chances are high that at least one will hinge upon one of these edge cases.