Image: via

Thursday, November 30, 2023

The Essential Larry McMurtry

“Texas has produced no major writers or major books,” wrote Larry Jeff McMurtry, rather despairingly, in 2011. He was being modest. McMurtry, who died in 2021 at 84, was himself an undisputed titan of the Lone Star State and a wildly prolific one at that. During his lifetime, McMurtry published 33 novels and a baker’s dozen of memoirs, essays and assorted balooey. McMurtry’s best-known works weren’t just major — they became major motion pictures like “Hud” (adapted from “Horseman, Pass By”), “The Last Picture Show” and “Terms of Endearment.” And the rest were only as minor as the descending chords in a bluegrass ballad, idiosyncratic variations on a warm and wistful twang. You don’t need to know all the songs by heart for the melodies to linger.

McMurtry’s life, like his bulging bibliography, is tough to get one’s arms around. (To paraphrase a regional cliché, everything is bigger in a McMurtry novel — especially the page count.) Raised on the outskirts of tiny Archer City, Texas, to a cattle-ranching family and educated in the California hills of Berkeley alongside Wendell Berry and Ken Kesey, McMurtry was a tangle of contradictions. He was a known crank and an infamous flirt; a small-town bohemian; an Oscar winner (for adapting “Brokeback Mountain”) and a pathological antiquarian.

But, through it all, he was a writer — averaging between five and 10 pages a day of something, every morning, for decades. And though he was an unlikely exemplar of his home state in appearance — teetotaling, bespectacled, with a mild phobia of horses — Larry McMurtry was, in fact, a peerless interlocutor of Texas, bridging the gap between its rural past and its noisy, urban present. And despite dalliances on the West Coast (with Cybill Shepherd and Diane Keaton, among others) and expensive habits (rooms at the Chateau Marmont, caviar at Petrossian), he always returned, somewhat grudgingly, to his birthplace. By refusing to let Texas define him, he helped redefine it.

For someone with such a keen and penetrating voice, he sure loved to listen. In a McMurtry book, everyone is interesting — even tertiary characters are a riot of quirk and detail. And, most notably for a white male writer of a certain age, McMurtry was fascinated by women, not in an objectifying manner, but rather with a dogged, almost courtly interest in the particulars of their lives.

Where most authors would align themselves with the swashbuckling rangers of the Lonesome Dove tetralogy, the most revealing character in the extended McMurtryverse might be the least likely: Patsy Carpenter, the winsome protagonist of the novel “Moving On,” who spends her happiest hours curled up in a rickety Ford with a melted Hershey’s bar and a box of old paperbacks. “Sometimes she ate casually and read avidly — other times she read casually and ate avidly,” he wrote of her and likely of himself, too.

“One of McMurtry’s aims in ‘Lonesome Dove’ was to pierce the romantic image of the trail-riding cowboy,” Tracy Daugherty writes in his recent biography. And the novel does its level best: As two retired Texas Rangers, Gus McCrae and Woodrow Call, lead a cattle drive from the Rio Grande to Montana, their quixotic caravan encounters the worst the world has to offer. The young and innocent die terrible deaths; the open country, far from romantic, is arid and hostile. “It’s mostly bones we’re riding over anyway,” Gus thinks, in a cheerful attempt to keep despair at bay.

And yet the book — which began life as a proposed screenplay that would bring James Stewart, Gary Cooper and John Wayne back for one last rodeo — is undeniable, awash in wit and wonder. With a canvas close to 1,000 pages, painted like a prairie sunset across a proscenium of sky, “Lonesome Dove” remains one of the best and happiest reading experiences of my life. To McMurtry’s chagrin, few myths were busted — in fact, quite the opposite. Multiple generations have now replaced their memories of the Alamo with those of the Hat Creek Cattle Company: something else rather foolish, noble and fleeting that’s nonetheless impossible to forget."

McMurtry’s life, like his bulging bibliography, is tough to get one’s arms around. (To paraphrase a regional cliché, everything is bigger in a McMurtry novel — especially the page count.) Raised on the outskirts of tiny Archer City, Texas, to a cattle-ranching family and educated in the California hills of Berkeley alongside Wendell Berry and Ken Kesey, McMurtry was a tangle of contradictions. He was a known crank and an infamous flirt; a small-town bohemian; an Oscar winner (for adapting “Brokeback Mountain”) and a pathological antiquarian.

But, through it all, he was a writer — averaging between five and 10 pages a day of something, every morning, for decades. And though he was an unlikely exemplar of his home state in appearance — teetotaling, bespectacled, with a mild phobia of horses — Larry McMurtry was, in fact, a peerless interlocutor of Texas, bridging the gap between its rural past and its noisy, urban present. And despite dalliances on the West Coast (with Cybill Shepherd and Diane Keaton, among others) and expensive habits (rooms at the Chateau Marmont, caviar at Petrossian), he always returned, somewhat grudgingly, to his birthplace. By refusing to let Texas define him, he helped redefine it.

For someone with such a keen and penetrating voice, he sure loved to listen. In a McMurtry book, everyone is interesting — even tertiary characters are a riot of quirk and detail. And, most notably for a white male writer of a certain age, McMurtry was fascinated by women, not in an objectifying manner, but rather with a dogged, almost courtly interest in the particulars of their lives.

Where most authors would align themselves with the swashbuckling rangers of the Lonesome Dove tetralogy, the most revealing character in the extended McMurtryverse might be the least likely: Patsy Carpenter, the winsome protagonist of the novel “Moving On,” who spends her happiest hours curled up in a rickety Ford with a melted Hershey’s bar and a box of old paperbacks. “Sometimes she ate casually and read avidly — other times she read casually and ate avidly,” he wrote of her and likely of himself, too.

by Andy Greenwald, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Diana Walker/Getty Images via

[ed. Had to look up pathological antiquarian. See also: A Literary Hero, Keeping the Last Bookshop Alive (NYT).]

“Lonesome Dove” (1985), a.k.a. Your Dad’s Favorite Novel, is the book McMurtry avoided writing for the first half of his life — and spent the second half of his life relitigating. Like Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” (released the year before), the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Lonesome Dove” is a masterpiece of missed intentions.

“Lonesome Dove” (1985), a.k.a. Your Dad’s Favorite Novel, is the book McMurtry avoided writing for the first half of his life — and spent the second half of his life relitigating. Like Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” (released the year before), the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Lonesome Dove” is a masterpiece of missed intentions.

“One of McMurtry’s aims in ‘Lonesome Dove’ was to pierce the romantic image of the trail-riding cowboy,” Tracy Daugherty writes in his recent biography. And the novel does its level best: As two retired Texas Rangers, Gus McCrae and Woodrow Call, lead a cattle drive from the Rio Grande to Montana, their quixotic caravan encounters the worst the world has to offer. The young and innocent die terrible deaths; the open country, far from romantic, is arid and hostile. “It’s mostly bones we’re riding over anyway,” Gus thinks, in a cheerful attempt to keep despair at bay.

And yet the book — which began life as a proposed screenplay that would bring James Stewart, Gary Cooper and John Wayne back for one last rodeo — is undeniable, awash in wit and wonder. With a canvas close to 1,000 pages, painted like a prairie sunset across a proscenium of sky, “Lonesome Dove” remains one of the best and happiest reading experiences of my life. To McMurtry’s chagrin, few myths were busted — in fact, quite the opposite. Multiple generations have now replaced their memories of the Alamo with those of the Hat Creek Cattle Company: something else rather foolish, noble and fleeting that’s nonetheless impossible to forget."

Wednesday, November 29, 2023

Tiger's Golf Equipment - 2023 Hero World Challenge

Tiger Woods' golf equipment at the 2023 Hero World Challenge (Golfweek)

Image: Adam Schupak/Golfweek

[ed. Golf nerd alert. My son has these clubs (not the TW version), and they're great. Wedge is rusted purposely for grabby-ness. Apparently an M grind of some sort (see below for examples of various grind options):]

[ed. Golf nerd alert. My son has these clubs (not the TW version), and they're great. Wedge is rusted purposely for grabby-ness. Apparently an M grind of some sort (see below for examples of various grind options):]

- L Grind: lowest bounce option with a lot of versatility; the L Grind is best for the better player looking for more control around the greens.

- F Grind: an all-purpose wedge used for more full swing shots; we like this one in a pitching wedge or gap wedge loft; some may even find this to be versatile for a sand wedge.

- M Grind: to remember what M grind stands for, we always think about the “most” versatile; for golfers that like to manipulate the clubface, the M Grind is a great option in a variety of lofts.

- S Grind: the S Grind is a narrower-looking wedge designed for golfers that like to hit square face shots; if you don’t play with the clubhead all that much, the S Grind is a good choice.

- D Grind: the D Grind is a high bounce wedge that works well for golfers that have a steeper swing and need more bounce to get through the turf.

- K Grind: Titleist calls the K Grind the ultimate bunker club as it has the highest bounce and is built for those that prefer playing shots with a bit more forgiveness in softer turf conditions.

Not Just Electricity — Bitcoin Mines Burn Through a Lot of Water, Too

It’s not just electricity — Bitcoin mines burn through a lot of water, too (The Verge)

There’s another way to get the cryptocurrency to use a fraction of the water and electricity it eats up now and slash greenhouse gas emissions: get rid of the mining process altogether and find a new way to validate transactions. That’s what the next biggest cryptocurrency network, Ethereum, accomplished last year. (Ethereum just completed The Merge — here’s how much energy it’s saving):

"Ethereum’s electricity use is expected to drop by a whopping 99.988 percent post-Merge, according to the analysis published today by research company Crypto Carbon Ratings Institute (CCRI). The network was previously using about 23 million megawatt-hours per year, CCRI estimates."

Report: Justine Calma. Image: Andrey Rudakov/Bloomberg via Getty Images

"Bitcoin mines aren’t just energy-hungry, it turns out they’re thirsty, too. The water consumption tied to a single Bitcoin transaction, on average, could be enough to fill a small backyard pool, according to a new analysis. Bitcoin mines are essentially big data centers, which have become notorious for how much electricity and water they use. (...)

All in all... cryptocurrency mining used about 1,600 gigaliters of water in 2021 when the price of Bitcoin peaked at over $65,000. That comes out to a small swimming pool’s worth of water (16,000 liters), on average, for each transaction. It’s about 6.2 million times more water than a credit card swipe."

"Bitcoin mines aren’t just energy-hungry, it turns out they’re thirsty, too. The water consumption tied to a single Bitcoin transaction, on average, could be enough to fill a small backyard pool, according to a new analysis. Bitcoin mines are essentially big data centers, which have become notorious for how much electricity and water they use. (...)

All in all... cryptocurrency mining used about 1,600 gigaliters of water in 2021 when the price of Bitcoin peaked at over $65,000. That comes out to a small swimming pool’s worth of water (16,000 liters), on average, for each transaction. It’s about 6.2 million times more water than a credit card swipe."

There’s another way to get the cryptocurrency to use a fraction of the water and electricity it eats up now and slash greenhouse gas emissions: get rid of the mining process altogether and find a new way to validate transactions. That’s what the next biggest cryptocurrency network, Ethereum, accomplished last year. (Ethereum just completed The Merge — here’s how much energy it’s saving):

"Ethereum’s electricity use is expected to drop by a whopping 99.988 percent post-Merge, according to the analysis published today by research company Crypto Carbon Ratings Institute (CCRI). The network was previously using about 23 million megawatt-hours per year, CCRI estimates."

Labels:

Business,

Economics,

Environment,

Science,

Technology

The Moral Injury of Having Your Work Enshittified

This week, I wrote about how the Great Enshittening – in which all the digital services we rely on become unusable, extractive piles of shit – did not result from the decay of the morals of tech company leadership, but rather, from the collapse of the forces that discipline corporate wrongdoing. (...)

Undisciplined by the threat of competition, regulation, or unilateral modification by users, companies are free to enshittify their products. But what does that actually look like? I say that enshittification is always precipitated by a lost argument.

But when you take away that discipline, the argument gets reduced to, "Don't do this because it would make me ashamed to work here, even though it will make the company richer." Money talks, bullshit walks. Let the enshittification begin!

But why do workers care at all? That's where phrases like "don't be evil" come into the picture. Until very recently, tech workers participated in one of history's tightest labor markets, in which multiple companies with gigantic war-chests bid on their labor. Even low-level employees routinely fielded calls from recruiters who dangled offers of higher salaries and larger stock grants if they would jump ship for a company's rival.

Employers built "campuses" filled with lavish perks: massages, sports facilities, daycare, gourmet cafeterias. They offered workers generous benefit packages, including exotic health benefits like having your eggs frozen so you could delay fertility while offsetting the risks normally associated with conceiving at a later age.

But all of this was a transparent ruse: the business-case for free meals, gyms, dry-cleaning, catering and massages was to keep workers at their laptops for 10, 12, or even 16 hours per day. That egg-freezing perk wasn't about helping workers plan their families: it was about thumbing the scales in favor of working through your entire twenties and thirties without taking any parental leave.

In other words, tech employers valued their employees as a means to an end: they wanted to get the best geeks on the payroll and then work them like government mules. The perks and pay weren't the result of comradeship between management and labor: they were the result of the discipline of competition for labor.

This wasn't really a secret, of course. Big Tech workers are split into two camps: blue badges (salaried employees) and green badges (contractors). Whenever there is a slack labor market for a specific job or skill, it is converted from a blue badge job to a green badge job. Green badges don't get the food or the massages or the kombucha. They don't get stock or daycare. They don't get to freeze their eggs. They also work long hours, but they are incentivized by the fear of poverty.

Tech giants went to great lengths to shield blue badges from green badges – at some Google campuses, these workforces actually used different entrances and worked in different facilities or on different floors. Sometimes, green badge working hours would be staggered so that the armies of ragged clickworkers would not be lined up to badge in when their social betters swanned off the luxury bus and into their airy adult kindergartens.

But Big Tech worked hard to convince those blue badges that they were truly valued. Companies hosted regular town halls where employees could ask impertinent questions of their CEOs. They maintained freewheeling internal social media sites where techies could rail against corporate foolishness and make Dilbert references. (...)

And Google promised its employees that they would not "be evil" if they worked at Google. For many googlers, that mattered. They wanted to do something good with their lives, and they had a choice about who they would work for. What's more, they did make things that were good. At their high points, Google Maps, Google Mail, and of course, Google Search were incredible.

My own life was totally transformed by Maps: I have very poor spatial sense, need to actually stop and think to tell my right from my left, and I spent more of my life at least a little lost and often very lost. Google Maps is the cognitive prosthesis I needed to become someone who can go anywhere. I'm profoundly grateful to the people who built that service.

There's a name for phenomenon in which you care so much about your job that you endure poor conditions and abuse: it's called "vocational awe," as coined by Fobazi Ettarh.

Ettarh uses the term to apply to traditionally low-waged workers like librarians, teachers and nurses. In our book Chokepoint Capitalism, Rebecca Giblin and I talked about how it applies to artists and other creative workers, too.

But vocational awe is also omnipresent in tech. The grandiose claims to be on a mission to make the world a better place are not just puffery – they're a vital means of motivating workers who can easily quit their jobs and find a new one to put in 16-hour days. The massages and kombucha and egg-freezing are not framed as perks, but as logistical supports, provided so that techies on an important mission can pursue a shared social goal without being distracted by their balky, inconvenient meatsuits.

Steve Jobs was a master of instilling vocational awe. He was full of aphorisms like "we're here to make a dent in the universe, otherwise why even be here?" Or his infamous line to John Sculley, whom he lured away from Pepsi: "Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life or come with me and change the world?"

Vocational awe cuts both ways. If your workforce actually believes in all that high-minded stuff, if they actually sacrifice their health, family lives and self-care to further the mission, they will defend it. That brings me back to enshittification, and the argument: "If we do this bad thing to the product I work on, it will make me hate myself."

The decline in market discipline for large tech companies has been accompanied by a decline in labor discipline, as the market for technical work grew less and less competitive. Since the dotcom collapse, the ability of tech giants to starve new entrants of market oxygen has shrunk techies' dreams.

Tech workers once dreamed of working for a big, unwieldy firm for a few years before setting out on their own to topple it with a startup. Then, the dream shrank: work for that big, clumsy firm for a few years, then do a fake startup that makes a fake product that is acquired by your old employer, as an incredibly inefficient and roundabout way to get a raise and a bonus.

Then the dream shrank again: work for a big, ugly firm for life, but get those perks, the massages and the kombucha and the stock options and the gourmet cafeteria and the egg-freezing. Then it shrank again: work for Google for a while, but then get laid off along with 12,000 co-workers, just months after the company does a stock buyback that would cover all those salaries for the next 27 years.

Tech workers' power was fundamentally individual. In a tight labor market, tech workers could personally stand up to their bosses. They got "workplace democracy" by mouthing off at town hall meetings. They didn't have a union, and they thought they didn't need one. Of course, they did need one, because there were limits to individual power, even for the most in-demand workers, especially when it came to ghastly, long-running sexual abuse from high-ranking executives:

Today, atomized tech workers who are ordered to enshittify the products they take pride in are losing the argument. Workers who put in long hours, missed funerals and school plays and little league games and anniversaries and family vacations are being ordered to flush that sacrifice down the toilet to grind out a few basis points towards a KPI.

It's a form of moral injury, and it's palpable in the first-person accounts of former workers who've exited these large firms or the entire field. The viral "Reflecting on 18 years at Google," written by Ian Hixie, vibrates with it:

Hixie describes the sense of mission he brought to his job, the workplace democracy he experienced as employees' views were both solicited and heeded. He describes the positive contributions he was able to make to a commons of technical standards that rippled out beyond Google – and then, he says, "Google's culture eroded":

Hixie attributes the changes to a change in leadership, but I respectfully disagree. Hixie points to the original shareholder letter from the Google founders, in which they informed investors contemplating their IPO that they were retaining a controlling interest in the company's governance so that they could ignore their shareholders' priorities in favor of a vision of Google as a positive force in the world.

Hixie says that the leadership that succeeded the founders lost sight of this vision – but the whole point of that letter is that the founders never fully ceded control to subsequent executive teams. Yes, those executive teams were accountable to the shareholders, but the largest block of voting shares were retained by the founders.

I don't think the enshittification of Google was due to a change in leadership – I think it was due to a change in discipline, the discipline imposed by competition, regulation and the threat of self-help measures. (...)

This is bad news for people like me, who rely on services like Google Maps as cognitive prostheses. Elizabeth Laraki, one of the original Google Maps designers, has published a scorching critique of the latest GMaps design.

Laraki calls out numerous enshittificatory design-choices that have left Maps screens covered in "crud" – multiple revenue-maximizing elements that come at the expense of usability, shifting value from users to Google.

What Laraki doesn't say is that these UI elements are auctioned off to merchants, which means that the business that gives Google the most money gets the greatest prominence in Maps, even if it's not the best merchant. That's a recurring motif in enshittified tech platforms, most notoriously Amazon, which makes $31b/year auctioning off top search placement to companies whose products aren't relevant enough to your query to command that position on their own.

Enshittification begets enshittification. To succeed on Amazon, you must divert funds from product quality to auction placement, which means that the top results are the worst products.

The exception is searches for Apple products: Apple and Amazon have a cozy arrangement that means that searches for Apple products are a timewarp back to the pre-enshittification Amazon, when the company worried enough about losing your business to heed the employees who objected to sacrificing search quality as part of a merchant extortion racket.

Not every tech worker is a tech bro, in other words. Many workers care deeply about making your life better. But the microeconomics of the boardroom in a monopolized tech sector rewards the worst people and continuously promotes them. Forget the Peter Principle: tech is ruled by the Sam Principle.

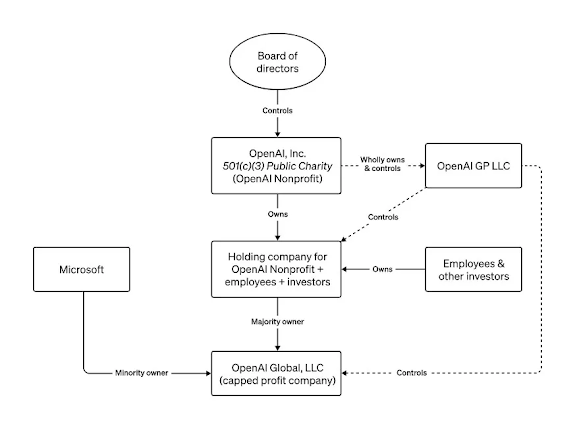

As OpenAI went through four CEOs in a single week, lots of commentators remarked on Sam Altman's rise and fall and rise, but I only found one commentator who really had Altman's number. Writing in Today in Tabs, Rusty Foster nailed Altman to the wall:

Altman's history goes like this: first, he founded a useless startup that raised $30m, only to be acquired and shuttered. Then Altman got a job running Y Combinator, where he somehow failed at taking huge tranches of equity from "every Stanford dropout with an idea for software to replace something Mommy used to do." After that, he founded OpenAI, a company that he claims to believe presents an existential risk to the entire human risk – which he structured so incompetently that he was then forced out of it.

His reward for this string of farcical, mounting failures? He was put back in charge of the company he mis-structured despite his claimed belief that it will destroy the human race if not properly managed.

"Imagine I awoke one morning from troubled dreams to find myself transformed in my bed into someone with an idea for how, if a global mega-corporation gave me tens of billions of dollars, and if I could collect a thousand of the smartest scientists, engineers, and coders who have ever lived, and if I had access to quantities of energy and computing power that would stretch the limits of what is technically imaginable in the next decade, I could build a machine that would relentlessly turn every atom of matter in the universe into paper clips. I feel like I would… simply not do that. Should I devote a huge amount of expense and effort to accomplish something objectively terrible? It’s not even a tough call for me, a person with what I flatter myself is a normal working brain.

But however implausible it is, imagine that instead of thinking “lol no?” someone had that idea and thought “lol, I better build this machine so that rather than paper clips, it will turn every atom of the universe into something positive for humanity, like ice cream.” This is incredibly stupid and abstrusely metaphysical, but also a pretty accurate overview of today’s business news. Yes, regrettably, I’m talking about OpenAI."

It starts when someone around a board-room table proposes doing something that's bad for users but good for the company. If the company faces the discipline of competition, regulation or self-help measures, then the workers who are disgusted by this course of action can say, "I think doing this would be gross, and what's more, it's going to make the company poorer," and so they win the argument.

But when you take away that discipline, the argument gets reduced to, "Don't do this because it would make me ashamed to work here, even though it will make the company richer." Money talks, bullshit walks. Let the enshittification begin!

But why do workers care at all? That's where phrases like "don't be evil" come into the picture. Until very recently, tech workers participated in one of history's tightest labor markets, in which multiple companies with gigantic war-chests bid on their labor. Even low-level employees routinely fielded calls from recruiters who dangled offers of higher salaries and larger stock grants if they would jump ship for a company's rival.

Employers built "campuses" filled with lavish perks: massages, sports facilities, daycare, gourmet cafeterias. They offered workers generous benefit packages, including exotic health benefits like having your eggs frozen so you could delay fertility while offsetting the risks normally associated with conceiving at a later age.

But all of this was a transparent ruse: the business-case for free meals, gyms, dry-cleaning, catering and massages was to keep workers at their laptops for 10, 12, or even 16 hours per day. That egg-freezing perk wasn't about helping workers plan their families: it was about thumbing the scales in favor of working through your entire twenties and thirties without taking any parental leave.

In other words, tech employers valued their employees as a means to an end: they wanted to get the best geeks on the payroll and then work them like government mules. The perks and pay weren't the result of comradeship between management and labor: they were the result of the discipline of competition for labor.

This wasn't really a secret, of course. Big Tech workers are split into two camps: blue badges (salaried employees) and green badges (contractors). Whenever there is a slack labor market for a specific job or skill, it is converted from a blue badge job to a green badge job. Green badges don't get the food or the massages or the kombucha. They don't get stock or daycare. They don't get to freeze their eggs. They also work long hours, but they are incentivized by the fear of poverty.

Tech giants went to great lengths to shield blue badges from green badges – at some Google campuses, these workforces actually used different entrances and worked in different facilities or on different floors. Sometimes, green badge working hours would be staggered so that the armies of ragged clickworkers would not be lined up to badge in when their social betters swanned off the luxury bus and into their airy adult kindergartens.

But Big Tech worked hard to convince those blue badges that they were truly valued. Companies hosted regular town halls where employees could ask impertinent questions of their CEOs. They maintained freewheeling internal social media sites where techies could rail against corporate foolishness and make Dilbert references. (...)

And Google promised its employees that they would not "be evil" if they worked at Google. For many googlers, that mattered. They wanted to do something good with their lives, and they had a choice about who they would work for. What's more, they did make things that were good. At their high points, Google Maps, Google Mail, and of course, Google Search were incredible.

My own life was totally transformed by Maps: I have very poor spatial sense, need to actually stop and think to tell my right from my left, and I spent more of my life at least a little lost and often very lost. Google Maps is the cognitive prosthesis I needed to become someone who can go anywhere. I'm profoundly grateful to the people who built that service.

There's a name for phenomenon in which you care so much about your job that you endure poor conditions and abuse: it's called "vocational awe," as coined by Fobazi Ettarh.

Ettarh uses the term to apply to traditionally low-waged workers like librarians, teachers and nurses. In our book Chokepoint Capitalism, Rebecca Giblin and I talked about how it applies to artists and other creative workers, too.

But vocational awe is also omnipresent in tech. The grandiose claims to be on a mission to make the world a better place are not just puffery – they're a vital means of motivating workers who can easily quit their jobs and find a new one to put in 16-hour days. The massages and kombucha and egg-freezing are not framed as perks, but as logistical supports, provided so that techies on an important mission can pursue a shared social goal without being distracted by their balky, inconvenient meatsuits.

Steve Jobs was a master of instilling vocational awe. He was full of aphorisms like "we're here to make a dent in the universe, otherwise why even be here?" Or his infamous line to John Sculley, whom he lured away from Pepsi: "Do you want to sell sugar water for the rest of your life or come with me and change the world?"

Vocational awe cuts both ways. If your workforce actually believes in all that high-minded stuff, if they actually sacrifice their health, family lives and self-care to further the mission, they will defend it. That brings me back to enshittification, and the argument: "If we do this bad thing to the product I work on, it will make me hate myself."

The decline in market discipline for large tech companies has been accompanied by a decline in labor discipline, as the market for technical work grew less and less competitive. Since the dotcom collapse, the ability of tech giants to starve new entrants of market oxygen has shrunk techies' dreams.

Tech workers once dreamed of working for a big, unwieldy firm for a few years before setting out on their own to topple it with a startup. Then, the dream shrank: work for that big, clumsy firm for a few years, then do a fake startup that makes a fake product that is acquired by your old employer, as an incredibly inefficient and roundabout way to get a raise and a bonus.

Then the dream shrank again: work for a big, ugly firm for life, but get those perks, the massages and the kombucha and the stock options and the gourmet cafeteria and the egg-freezing. Then it shrank again: work for Google for a while, but then get laid off along with 12,000 co-workers, just months after the company does a stock buyback that would cover all those salaries for the next 27 years.

Tech workers' power was fundamentally individual. In a tight labor market, tech workers could personally stand up to their bosses. They got "workplace democracy" by mouthing off at town hall meetings. They didn't have a union, and they thought they didn't need one. Of course, they did need one, because there were limits to individual power, even for the most in-demand workers, especially when it came to ghastly, long-running sexual abuse from high-ranking executives:

Today, atomized tech workers who are ordered to enshittify the products they take pride in are losing the argument. Workers who put in long hours, missed funerals and school plays and little league games and anniversaries and family vacations are being ordered to flush that sacrifice down the toilet to grind out a few basis points towards a KPI.

It's a form of moral injury, and it's palpable in the first-person accounts of former workers who've exited these large firms or the entire field. The viral "Reflecting on 18 years at Google," written by Ian Hixie, vibrates with it:

Hixie describes the sense of mission he brought to his job, the workplace democracy he experienced as employees' views were both solicited and heeded. He describes the positive contributions he was able to make to a commons of technical standards that rippled out beyond Google – and then, he says, "Google's culture eroded":

Decisions went from being made for the benefit of users, to the benefit of Google, to the benefit of whoever was making the decision.In other words, techies started losing the argument. Layoffs weakened worker power – not just to defend their own interest, but to defend the users interests. Worker power is always about more than workers – think of how the 2019 LA teachers' strike won greenspace for every school, a ban on immigration sweeps of students' parents at the school gates and other community benefits.

Hixie attributes the changes to a change in leadership, but I respectfully disagree. Hixie points to the original shareholder letter from the Google founders, in which they informed investors contemplating their IPO that they were retaining a controlling interest in the company's governance so that they could ignore their shareholders' priorities in favor of a vision of Google as a positive force in the world.

Hixie says that the leadership that succeeded the founders lost sight of this vision – but the whole point of that letter is that the founders never fully ceded control to subsequent executive teams. Yes, those executive teams were accountable to the shareholders, but the largest block of voting shares were retained by the founders.

I don't think the enshittification of Google was due to a change in leadership – I think it was due to a change in discipline, the discipline imposed by competition, regulation and the threat of self-help measures. (...)

This is bad news for people like me, who rely on services like Google Maps as cognitive prostheses. Elizabeth Laraki, one of the original Google Maps designers, has published a scorching critique of the latest GMaps design.

Laraki calls out numerous enshittificatory design-choices that have left Maps screens covered in "crud" – multiple revenue-maximizing elements that come at the expense of usability, shifting value from users to Google.

What Laraki doesn't say is that these UI elements are auctioned off to merchants, which means that the business that gives Google the most money gets the greatest prominence in Maps, even if it's not the best merchant. That's a recurring motif in enshittified tech platforms, most notoriously Amazon, which makes $31b/year auctioning off top search placement to companies whose products aren't relevant enough to your query to command that position on their own.

Enshittification begets enshittification. To succeed on Amazon, you must divert funds from product quality to auction placement, which means that the top results are the worst products.

The exception is searches for Apple products: Apple and Amazon have a cozy arrangement that means that searches for Apple products are a timewarp back to the pre-enshittification Amazon, when the company worried enough about losing your business to heed the employees who objected to sacrificing search quality as part of a merchant extortion racket.

Not every tech worker is a tech bro, in other words. Many workers care deeply about making your life better. But the microeconomics of the boardroom in a monopolized tech sector rewards the worst people and continuously promotes them. Forget the Peter Principle: tech is ruled by the Sam Principle.

As OpenAI went through four CEOs in a single week, lots of commentators remarked on Sam Altman's rise and fall and rise, but I only found one commentator who really had Altman's number. Writing in Today in Tabs, Rusty Foster nailed Altman to the wall:

Altman's history goes like this: first, he founded a useless startup that raised $30m, only to be acquired and shuttered. Then Altman got a job running Y Combinator, where he somehow failed at taking huge tranches of equity from "every Stanford dropout with an idea for software to replace something Mommy used to do." After that, he founded OpenAI, a company that he claims to believe presents an existential risk to the entire human risk – which he structured so incompetently that he was then forced out of it.

His reward for this string of farcical, mounting failures? He was put back in charge of the company he mis-structured despite his claimed belief that it will destroy the human race if not properly managed.

by Cory Doctorow, Pluralistic | Read more:

Image: uncredited

[ed. Some link modifications to enhance readability. See also: Confessions of a Middle-Class Founder (Intelligencer). And, from the Today in Tabs/Rusty Foster essay (Defective Accelerationism) on Sam Altman, mentioned above:]

"Imagine I awoke one morning from troubled dreams to find myself transformed in my bed into someone with an idea for how, if a global mega-corporation gave me tens of billions of dollars, and if I could collect a thousand of the smartest scientists, engineers, and coders who have ever lived, and if I had access to quantities of energy and computing power that would stretch the limits of what is technically imaginable in the next decade, I could build a machine that would relentlessly turn every atom of matter in the universe into paper clips. I feel like I would… simply not do that. Should I devote a huge amount of expense and effort to accomplish something objectively terrible? It’s not even a tough call for me, a person with what I flatter myself is a normal working brain.

But however implausible it is, imagine that instead of thinking “lol no?” someone had that idea and thought “lol, I better build this machine so that rather than paper clips, it will turn every atom of the universe into something positive for humanity, like ice cream.” This is incredibly stupid and abstrusely metaphysical, but also a pretty accurate overview of today’s business news. Yes, regrettably, I’m talking about OpenAI."

Labels:

Business,

Economics,

history,

Media,

Politics,

Psychology,

Relationships,

Technology

Tuesday, November 28, 2023

Perfectly Designed Climate Report Cover

Cover to the just-released: United Nations Environment Programme Emissions Gap Report 2023 (full report here).

Amazing that an official UN climate report has this much biting personality. You can just sense the no-fucks-givenness of the people who put this together. After all:

Image/Cover Design: Beverley McDonald

Amazing that an official UN climate report has this much biting personality. You can just sense the no-fucks-givenness of the people who put this together. After all:

Humanity is breaking all the wrong records when it comes to climate change. Greenhouse gas emissions reached a new high in 2022. In September 2023, global average temperatures were 1.8°C above pre-industrial levels. When this year is over, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, it is almost certain to be the warmest year on record.by Jason Kottke, Kottke.org | Read more:

The 2023 edition of the Emissions Gap Report tells us that the world must change track, or we will be saying the same thing next year — and the year after, and the year after, like a broken record. The report finds that fully implementing and continuing mitigation efforts of unconditional nationally determined contributions (NDCs) made under the Paris Agreement for 2030 would put the world on course for limiting temperature rise to 2.9°C this century. Fully implementing conditional NDCs would lower this to 2.5°C. Given the intense climate impacts we are already seeing, neither outcome is desirable.

Image/Cover Design: Beverley McDonald

Labels:

Art,

Design,

Environment,

Government,

Illustration,

Media,

Politics,

Science

Growing Pains

The Infancy Gospel of Thomas is a biographical gospel about the childhood of Jesus, believed to date at the latest to the second century.

Scholars generally agree on a date in the mid-to-late-2nd century AD. There are two 2nd-century documents, the Epistula Apostolorum and Irenaeus' Adversus haereses, that refer to a story of Jesus's tutor telling him, "Say alpha," and Jesus replied, "First tell me what is beta, and I can tell you what alpha is."

The text describes the life of the child Jesus from the ages of five to twelve, with fanciful, and sometimes malevolent, supernatural events. He is presented as a precocious child who starts his education early. The stories cover how the young Incarnation of God matures and learns to use his powers for good and how those around him first respond in fear and later with admiration. One of the episodes involves Jesus making clay birds, which he then proceeds to bring to life, an act also attributed to Jesus in Quran 5:110, and in a medieval Jewish work known as Toledot Yeshu, although Jesus's age at the time of the event is not specified in either account. In another episode, a child disperses water that Jesus has collected. Jesus kills this first child, when at age one he curses a boy, which causes the child's body to wither into a corpse. Later, Jesus kills another child via curse when the child apparently accidentally bumps into Jesus, throws a stone at Jesus, or punches Jesus (depending on the translation).

When Joseph and Mary's neighbors complain, Jesus miraculously strikes them blind. Jesus then starts receiving lessons, but tries to teach the teacher, instead, upsetting the teacher who suspects supernatural origins. Jesus is amused by this suspicion, which he confirms, and revokes all his earlier apparent cruelty. Subsequently, he resurrects a friend who is killed when he falls from a roof, and heals another who cuts his foot with an axe.

After various other demonstrations of supernatural ability, new teachers try to teach Jesus, but he proceeds to explain the law to them instead. Another set of miracles is mentioned, in which Jesus heals his brother, who is bitten by a snake, and two others, who have died from different causes. Finally, the text recounts the episode in Luke in which Jesus, aged 12, teaches in the temple.

by Wikipedia | Read more:

Images: Christ among the Doctors, c. 1560, by Paolo Veronese, a depiction of the Finding in the Temple; Jesus raises the clay birds of his playmates to life - Unknown artist (more)[ed. The things you learn every day. Given the bible's overall and some would say excrutiating detail, it seems odd that certain events, like the early life of Jesus, would be left inexplicably vague. Another example would be everything Jesus said and did after the Resurrection.]

Monday, November 27, 2023

I Can Tolerate Anything Except the Outgroup

In Chesterton’s The Secret of Father Brown, a beloved nobleman who murdered his good-for-nothing brother in a duel thirty years ago returns to his hometown wracked by guilt. All the townspeople want to forgive him immediately, and they mock the titular priest for only being willing to give a measured forgiveness conditional on penance and self-reflection. They lecture the priest on the virtues of charity and compassion.

Later, it comes out that the beloved nobleman did not in fact kill his good-for-nothing brother. The good-for-nothing brother killed the beloved nobleman (and stole his identity). Now the townspeople want to see him lynched or burned alive, and it is only the priest who – consistently – offers a measured forgiveness conditional on penance and self-reflection.

The priest tells them:

It seems to me that you only pardon the sins that you don’t really think sinful. You only forgive criminals when they commit what you don’t regard as crimes, but rather as conventions. You forgive a conventional duel just as you forgive a conventional divorce. You forgive because there isn’t anything to be forgiven.He further notes that this is why the townspeople can self-righteously consider themselves more compassionate and forgiving than he is. Actual forgiveness, the kind the priest needs to cultivate to forgive evildoers, is really really hard. The fake forgiveness the townspeople use to forgive the people they like is really easy, so they get to boast not only of their forgiving nature, but of how much nicer they are than those mean old priests who find forgiveness difficult and want penance along with it.

After some thought I agree with Chesterton’s point. There are a lot of people who say “I forgive you” when they mean “No harm done”, and a lot of people who say “That was unforgiveable” when they mean “That was genuinely really bad”. Whether or not forgiveness is right is a complicated topic I do not want to get in here. But since forgiveness is generally considered a virtue, and one that many want credit for having, I think it’s fair to say you only earn the right to call yourself ‘forgiving’ if you forgive things that genuinely hurt you.

To borrow Chesterton’s example, if you think divorce is a-ok, then you don’t get to “forgive” people their divorces, you merely ignore them. Someone who thinks divorce is abhorrent can “forgive” divorce. You can forgive theft, or murder, or tax evasion, or something you find abhorrent.

I mean, from a utilitarian point of view, you are still doing the correct action of not giving people grief because they’re a divorcee. You can have all the Utility Points you want. All I’m saying is that if you “forgive” something you don’t care about, you don’t earn any Virtue Points.

(by way of illustration: a billionaire who gives $100 to charity gets as many Utility Points as an impoverished pensioner who donates the same amount, but the latter gets a lot more Virtue Points)

Tolerance is also considered a virtue, but it suffers the same sort of dimished expectations forgiveness does.

The Emperor summons before him Bodhidharma and asks: “Master, I have been tolerant of innumerable gays, lesbians, bisexuals, asexuals, blacks, Hispanics, Asians, transgender people, and Jews. How many Virtue Points have I earned for my meritorious deeds?”

Bodhidharma answers: “None at all”.

The Emperor, somewhat put out, demands to know why.

Bodhidharma asks: “Well, what do you think of gay people?”

The Emperor answers: “What do you think I am, some kind of homophobic bigot? Of course I have nothing against gay people!”

And Bodhidharma answers: “Thus do you gain no merit by tolerating them!”

II.

If I had to define “tolerance” it would be something like “respect and kindness toward members of an outgroup”.

And today we have an almost unprecedented situation.

We have a lot of people – like the Emperor – boasting of being able to tolerate everyone from every outgroup they can imagine, loving the outgroup, writing long paeans to how great the outgroup is, staying up at night fretting that somebody else might not like the outgroup enough.

This is really surprising. It’s a total reversal of everything we know about human psychology up to this point. No one did any genetic engineering. No one passed out weird glowing pills in the public schools. And yet suddenly we get an entire group of people who conspicuously promote and defend their outgroups, the outer the better.

What is going on here? (...)

The people who are actually into this sort of thing sketch out a bunch of speculative tribes and subtribes, but to make it easier, let me stick with two and a half.

The Red Tribe is most classically typified by conservative political beliefs, strong evangelical religious beliefs, creationism, opposing gay marriage, owning guns, eating steak, drinking Coca-Cola, driving SUVs, watching lots of TV, enjoying American football, getting conspicuously upset about terrorists and commies, marrying early, divorcing early, shouting “USA IS NUMBER ONE!!!”, and listening to country music.

The Blue Tribe is most classically typified by liberal political beliefs, vague agnosticism, supporting gay rights, thinking guns are barbaric, eating arugula, drinking fancy bottled water, driving Priuses, reading lots of books, being highly educated, mocking American football, feeling vaguely like they should like soccer but never really being able to get into it, getting conspicuously upset about sexists and bigots, marrying later, constantly pointing out how much more civilized European countries are than America, and listening to “everything except country”.

(There is a partly-formed attempt to spin off a Grey Tribe typified by libertarian political beliefs, Dawkins-style atheism, vague annoyance that the question of gay rights even comes up, eating paleo, drinking Soylent, calling in rides on Uber, reading lots of blogs, calling American football “sportsball”, getting conspicuously upset about the War on Drugs and the NSA, and listening to filk – but for our current purposes this is a distraction and they can safely be considered part of the Blue Tribe most of the time)

I think these “tribes” will turn out to be even stronger categories than politics. (...)

VII.

Every election cycle like clockwork, conservatives accuse liberals of not being sufficiently pro-America. And every election cycle like clockwork, liberals give extremely unconvincing denials of this.

“It’s not that we’re, like, against America per se. It’s just that…well, did you know Europe has much better health care than we do? And much lower crime rates? I mean, come on, how did they get so awesome? And we’re just sitting here, can’t even get the gay marriage thing sorted out, seriously, what’s wrong with a country that can’t…sorry, what were we talking about? Oh yeah, America. They’re okay. Cesar Chavez was really neat. So were some other people outside the mainstream who became famous precisely by criticizing majority society. That’s sort of like America being great, in that I think the parts of it that point out how bad the rest of it are often make excellent points. Vote for me!”

(sorry, I make fun of you because I love you) (...)

My hunch – both the Red Tribe and the Blue Tribe, for whatever reason, identify “America” with the Red Tribe. Ask people for typically “American” things, and you end up with a very Red list of characteristics – guns, religion, barbecues, American football, NASCAR, cowboys, SUVs, unrestrained capitalism.

That means the Red Tribe feels intensely patriotic about “their” country, and the Blue Tribe feels like they’re living in fortified enclaves deep in hostile territory. (...)

That means the Red Tribe feels intensely patriotic about “their” country, and the Blue Tribe feels like they’re living in fortified enclaves deep in hostile territory. (...)

Spending your entire life insulting the other tribe and talking about how terrible they are makes you look, well, tribalistic. It is definitely not high class. So when members of the Blue Tribe decide to dedicate their entire life to yelling about how terrible the Red Tribe is, they make sure that instead of saying “the Red Tribe”, they say “America”, or “white people”, or “straight white men”. That way it’s humble self-criticism. They are so interested in justice that they are willing to critique their own beloved side, much as it pains them to do so. We know they are not exaggerating, because one might exaggerate the flaws of an enemy, but that anyone would exaggerate their own flaws fails the criterion of embarrassment.

by Scott Alexander, Slate Star Codex | Read more:

Image: Wikipedia

[ed. Dated, but same as it ever was (actually, worse). Wonder how this relates to pricing of carbon credits, farm subsidies, etc. re: utility vs. value points.]

Labels:

Critical Thought,

Culture,

Government,

history,

Media,

Politics,

Psychology

Can Golf Really Change?

If golf has a superpower, it’s the ability to fill the cracks in your mind and feast on your anxieties. First-tee jitters. Overthinking a putt. New players worriedly trying to figure out where to stand, where to go, what to do. Experienced players exasperated by every mistake, seeing the score they hoped to post slip away. All the fretting over playing too slow or waiting too long.

Then there’s the scoring. An arbitrary number decided by someone you never met. You thought you played that hole well, but this little card says you took a bogey. The word is born from a Scottish term for a devil. So now your terrible play is an incarnation of a fallen angel, expelled from heaven, abusing free will with its evil. Beelzebul is playing through.

But now imagine being handed a scorecard with no criterion. Some tees at 50 and 56 yards. Others at 101 and 111. And 164. And 218. And as far back as 293. One hole that can be played from 89 or 187. And on this card, a glaring omission. No par. Just play. Have a match against a friend. Grab a couple of clubs, a few beverages, and go. Winner of each hole decides where to tee off on the next hole. You can play a six-hole loop that circles a lovely grove of oak trees. Or play a 13-hole loop. Or play all 19. Who cares?

“You know,” Ben Crenshaw, the legendary golfer-turned-course architect, recently said, “this game is allowed to be played differently.”

So why don’t we more often?

A new course opening in central Florida makes the question again hard to ignore. The Chain, a “short course” created by Crenshaw and long-time design partner Bill Coore, is opening this month at Streamsong Golf Resort. Guests can currently play 13 holes total for preview play. The hope is to open the course’s full 19 by December 1, as long as the land allows. (...)

Like The Cradle at Pinehurst and others, each of those resorts features a funky short course. Now, so too does Streamsong. The feature has become a prerequisite for resort life. For guests, playing (especially walking) 36 holes over multiple consecutive days can be easier said than done. It’s far more enjoyable to play 18, then hit the short course for a loop. For the resorts, a short course is a draw, an extra amenity for the portfolio, uses little land, and, most importantly, encourages additional nights of stay-and-play.

Short courses make an incredible amount of sense in metropolitan areas stuck with hyper-exclusive courses and limited public options. They just need to be built there. Chicago, Washington D.C., Boston, Philadelphia — cities that require an hour drive to the course, a five-and-a-half hour round on a packed course, and an hour drive home. One imagines such players thirsty for such an option. The densest populated areas have the most potential golfers. There’s a reason Callaway paid $2.66 billion for Top Golf in 2021 — droves of people go because hitting golf balls is fun. Anyone who wants to transition from the driving range-esque Top Golf to learning the game on the golf course, though, has to tackle the tension that comes with playing with 14 clubs on a crowded, daunting 18-hole course, navigating all the worry and embarrassment of golf’s inordinate rules and customs. Envision new players instead getting to relax and come to understand how golf courses can be experienced.

Based on Johnson’s explanation of golf course architecture top-down composition, maybe we’ll see the success of courses like The Chain finally spur local municipalities and private developers into renovating pre-existing, nondescript public courses into alternative short courses.

This, in turn, could create an entirely new access point to the game. Yes, par-3 tracks already exist, but these resort-style short courses designed by the finest architects are nothing like what the average novice has seen — short does not have to mean simple. Is an entirely different experience. One that kids and newcomers would likely be far more prone to want to revisit.

“You’re showing the most fun version of golf,” Johnson said. “Bold design features. Cool greens. People getting to see the ball rolling and moving.”

This isn’t implausible. Designer short sources require only small plots of real estate and can be built anywhere — flat land, undulating land, choppier land. All you need is a spot for a tee and a spot for a green. (...)

But golf, as it so often does, moves slowly. The best chance for change is the math eventually adding up to create an inevitable shift. If renovating an entire public course can range from $5-$15 million, renovating or building a high-end par-3 course can get done for probably under a couple million dollars. What makes more sense for that community?

[ed. See also: A History of Swing Thoughts (GD).]

Then there’s the scoring. An arbitrary number decided by someone you never met. You thought you played that hole well, but this little card says you took a bogey. The word is born from a Scottish term for a devil. So now your terrible play is an incarnation of a fallen angel, expelled from heaven, abusing free will with its evil. Beelzebul is playing through.

But now imagine being handed a scorecard with no criterion. Some tees at 50 and 56 yards. Others at 101 and 111. And 164. And 218. And as far back as 293. One hole that can be played from 89 or 187. And on this card, a glaring omission. No par. Just play. Have a match against a friend. Grab a couple of clubs, a few beverages, and go. Winner of each hole decides where to tee off on the next hole. You can play a six-hole loop that circles a lovely grove of oak trees. Or play a 13-hole loop. Or play all 19. Who cares?

“You know,” Ben Crenshaw, the legendary golfer-turned-course architect, recently said, “this game is allowed to be played differently.”

So why don’t we more often?

A new course opening in central Florida makes the question again hard to ignore. The Chain, a “short course” created by Crenshaw and long-time design partner Bill Coore, is opening this month at Streamsong Golf Resort. Guests can currently play 13 holes total for preview play. The hope is to open the course’s full 19 by December 1, as long as the land allows. (...)

Like The Cradle at Pinehurst and others, each of those resorts features a funky short course. Now, so too does Streamsong. The feature has become a prerequisite for resort life. For guests, playing (especially walking) 36 holes over multiple consecutive days can be easier said than done. It’s far more enjoyable to play 18, then hit the short course for a loop. For the resorts, a short course is a draw, an extra amenity for the portfolio, uses little land, and, most importantly, encourages additional nights of stay-and-play.

The Chain is a portrait of why this works. Guests at Streamsong walk over a footbridge from the hotel, stop by a new 2-acre putting course (The Bucket), grab a carry bag to tote a few clubs, and play a 3,000-yard walking layout of holes that are — here’s the key — good enough to match the quality of the property’s three primary courses. Like any good short course, its character comes from its green complexes. Some wild and huge. Others are scaled-down and delicate. A certain personality exists in the green, one born from architectural freedom.

“You can take more liberties, or risks, so to speak, to do greens and surrounds that you may not be able to do on a regulation course, where you’re trying to adapt to people of such varying degrees or both strength and skill,” Coore said.

Highlights include a bunker positioned in the middle of the 6th green, conjuring Riviera’s famed sixth, and the lengthy 11th, a hole that can stretch back to nearly 200 yards over a lake into a mammoth punchbowl green.

But the real highlight is what The Chain, like so many of these quirky short courses, gives the players. It’s different. In a sport so steep in the individual pursuit, you and some friends instead walk together, talk together, drink together. In a sport so obsessed with numbers, there’s no real scoring. In a sport that’s so time-consuming, you’re through in an hour. In a sport so dictated by strength and length, skill gaps are leveled.

It is, in many ways, a much more enjoyable version of golf. (...)

“You can take more liberties, or risks, so to speak, to do greens and surrounds that you may not be able to do on a regulation course, where you’re trying to adapt to people of such varying degrees or both strength and skill,” Coore said.

Highlights include a bunker positioned in the middle of the 6th green, conjuring Riviera’s famed sixth, and the lengthy 11th, a hole that can stretch back to nearly 200 yards over a lake into a mammoth punchbowl green.

But the real highlight is what The Chain, like so many of these quirky short courses, gives the players. It’s different. In a sport so steep in the individual pursuit, you and some friends instead walk together, talk together, drink together. In a sport so obsessed with numbers, there’s no real scoring. In a sport that’s so time-consuming, you’re through in an hour. In a sport so dictated by strength and length, skill gaps are leveled.

It is, in many ways, a much more enjoyable version of golf. (...)

Short courses make an incredible amount of sense in metropolitan areas stuck with hyper-exclusive courses and limited public options. They just need to be built there. Chicago, Washington D.C., Boston, Philadelphia — cities that require an hour drive to the course, a five-and-a-half hour round on a packed course, and an hour drive home. One imagines such players thirsty for such an option. The densest populated areas have the most potential golfers. There’s a reason Callaway paid $2.66 billion for Top Golf in 2021 — droves of people go because hitting golf balls is fun. Anyone who wants to transition from the driving range-esque Top Golf to learning the game on the golf course, though, has to tackle the tension that comes with playing with 14 clubs on a crowded, daunting 18-hole course, navigating all the worry and embarrassment of golf’s inordinate rules and customs. Envision new players instead getting to relax and come to understand how golf courses can be experienced.

Based on Johnson’s explanation of golf course architecture top-down composition, maybe we’ll see the success of courses like The Chain finally spur local municipalities and private developers into renovating pre-existing, nondescript public courses into alternative short courses.

This, in turn, could create an entirely new access point to the game. Yes, par-3 tracks already exist, but these resort-style short courses designed by the finest architects are nothing like what the average novice has seen — short does not have to mean simple. Is an entirely different experience. One that kids and newcomers would likely be far more prone to want to revisit.

“You’re showing the most fun version of golf,” Johnson said. “Bold design features. Cool greens. People getting to see the ball rolling and moving.”

This isn’t implausible. Designer short sources require only small plots of real estate and can be built anywhere — flat land, undulating land, choppier land. All you need is a spot for a tee and a spot for a green. (...)

But golf, as it so often does, moves slowly. The best chance for change is the math eventually adding up to create an inevitable shift. If renovating an entire public course can range from $5-$15 million, renovating or building a high-end par-3 course can get done for probably under a couple million dollars. What makes more sense for that community?

by Brendan Quinn, The Athletic | Read more:

Image: Illustration: Sean Reilly/The Athletic; Photos: Courtesy Streamsong Resort, Matt Hahn

Labels:

Architecture,

Business,

Cities,

Design,

Environment,

Sports

Vanessa Smith — Vulture (oil and acrylic, on canvas, 2023)

Sunday, November 26, 2023

The Fall of My Teen-Age Self (And Time Travel: What If You Met Your Future Self?)

I've been thinking about teen-agers. I have one myself now, and of course I was one once—in a different world at a different moment—and can remember the feeling. Everything was extremity. It still is. Four waves of feminism, digital connectivity, a global wellness movement, the injunction to “be kind,” the commonplace “it gets better”—none of it seems to have put much of a dent in teen-age misery, especially not of the kind that concerns me. Watching girls gather outside the multiplexes this past summer, choosing between “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer,” I thought, Yeah, that pretty much sums it up. Brittle, impossible perfection on the one hand; apocalypse on the other. I have never forgotten the years I spent stretched between those two poles, and there was a time when I believed that the intensity of my girlhood memories made me somewhat unusual—even that this was what had made me a writer. I was disabused of that notion a long time ago, during the early days of social networks. Friends Reunited, Facebook. Turns out there’s a whole lot of people in this world who feel they never lived as intensely as they did that one particular summer. “If teen-age me could see me now, she’d be so disgusted! ” I said that to a shrink, a few years ago. To which the shrink replied, “Why assume your fifteen-year-old self is the arbiter of all truth?” Well, it’s a good point, but it hasn’t stopped me from carrying her around on my shoulder. I don’t suppose, at this point, I’ll ever be rid of her. (...)

Sometimes I ask myself: What would teen-age me do with her misery now? Where can a twenty-first-century girl go these days to retreat from reality? (If the answer “the Internet” comes to mind, I’m guessing you’re either over fifty or else somehow still able to imagine the Internet as separate from “reality.”) I worry that the avenues of escape have narrowed. Whatever else I used to think about time, for example, the one thing I never had to think about was whether or not there would be enough of it, existentially speaking. But now the end of time itself—apocalypse—is, for the average teen-ager, an entirely familiar and domesticated concept. I don’t remember taking Y2K seriously, but I bet I’d be a 2038 truther now. And to whom would my funeral orations be directed? My realm of potential envy would no longer be limited to just the people in my school or my neighborhood. Now it would stretch to as many people as my phone could conjure—that is, to all the people in the world. I’d like to think Prince would still be mediating my world to some degree, but I know he would be infinitely tinier than he was before, reduced to a speck in an epic web of digital mediation so huge and complex as to seem almost cosmic. I imagine I would be having a very hard time deciding if what I actually willed was what I appeared to be willing. Do I really love my lengthy skin-care regime? Do I truly want to queue all night to purchase the latest iteration of my device? Does this social network genuinely make me feel happy and connected to others? Or did some unseen commercial entity decide all that for me? I don’t think teen-age misery is so very different from what it used to be, but I do think its scope of operation is so much larger and the space for respite vanishingly small. But I would think that: I’m forty-eight.

Sometimes I ask myself: What would teen-age me do with her misery now? Where can a twenty-first-century girl go these days to retreat from reality? (If the answer “the Internet” comes to mind, I’m guessing you’re either over fifty or else somehow still able to imagine the Internet as separate from “reality.”) I worry that the avenues of escape have narrowed. Whatever else I used to think about time, for example, the one thing I never had to think about was whether or not there would be enough of it, existentially speaking. But now the end of time itself—apocalypse—is, for the average teen-ager, an entirely familiar and domesticated concept. I don’t remember taking Y2K seriously, but I bet I’d be a 2038 truther now. And to whom would my funeral orations be directed? My realm of potential envy would no longer be limited to just the people in my school or my neighborhood. Now it would stretch to as many people as my phone could conjure—that is, to all the people in the world. I’d like to think Prince would still be mediating my world to some degree, but I know he would be infinitely tinier than he was before, reduced to a speck in an epic web of digital mediation so huge and complex as to seem almost cosmic. I imagine I would be having a very hard time deciding if what I actually willed was what I appeared to be willing. Do I really love my lengthy skin-care regime? Do I truly want to queue all night to purchase the latest iteration of my device? Does this social network genuinely make me feel happy and connected to others? Or did some unseen commercial entity decide all that for me? I don’t think teen-age misery is so very different from what it used to be, but I do think its scope of operation is so much larger and the space for respite vanishingly small. But I would think that: I’m forty-eight.

by Zadie Smith, New Yorker | Read more:

Image: Yuki Sugiura; Source photograph by Daisy Houghton

[ed. See also: Time travel: What if you met your future self? (BBC):]

"There's a classic short story by Ted Chiang in which a young merchant travels years ahead and meets his future self. Over the course of the story, the man receives warnings, promises and tips from the older, wiser version of himself. These premonitions then change the course of the merchant's life until he eventually becomes an older man, who meets his younger self and imparts the same wisdom.

Scenarios like this are wildly popular and have been explored in many other novels as well as in movies like Back to the Future, and TV shows as diverse as Family Guy, Quantum Leap, and the BBC's own Doctor Who (see "The Doctor meets The Doctor" below).

For obvious reasons, these narratives have always been relegated to the realm of science fiction. But what if – and it is a big what if – you could meet your future self? What a very strange question, but one that I believe is worth asking. (...)

Now, imagine conversing with that future version of you in the same way you might chat with a friend or loved one now. What would you ask? My own knee-jerk response – and that of other people I’ve discussed it with – is often resistance. The source of this, I think, boils down to our desire to see ourselves as unique. How, we wonder, could an algorithm make a prediction about me – me with my many-coloured feathers that make me one in eight billion?

Yet I must accept – grudgingly – that I am not as unique as I like to think, and algorithms already predict my personality, desires and choices on a regular basis. Every time I listen to a personalised Spotify playlist, or love a Netflix film recommendation, a form of AI has predicted it. As these algorithms get more powerful, with greater access to data about us and other similar people, there's no reason they couldn't go beyond surface-level details like your future self's entertainment choices. They might be able to predict how the older, wiser version of you might feel about the decisions in your life.

Eight questions to ask "future you"

So, to return to my original question: if you could time-travel to meet your future self, what aspects of your life would you want to know more about? Which ones would you prefer to be shrouded in secrecy? And if you’d pass up on the meeting, why?

I've been thinking a lot about what I would do. My first instinct would be to ask my future self things like… are you happy? Are your family members happy and healthy? Is the environment safe for your grandkids and great-grandkids?

The more I considered these initial questions, the more I realised just how much I was concerned with what the future holds. A very informal survey of my wife and a few friends suggests I may not be alone in this tendency.

But reflecting on it further, I realised that the most powerful questions would be ones that helped me make better choices today. With that as the goal, I might generate several queries meant to kick off a dialogue between my two selves, such as:

[ed. See also: Time travel: What if you met your future self? (BBC):]

"There's a classic short story by Ted Chiang in which a young merchant travels years ahead and meets his future self. Over the course of the story, the man receives warnings, promises and tips from the older, wiser version of himself. These premonitions then change the course of the merchant's life until he eventually becomes an older man, who meets his younger self and imparts the same wisdom.

Scenarios like this are wildly popular and have been explored in many other novels as well as in movies like Back to the Future, and TV shows as diverse as Family Guy, Quantum Leap, and the BBC's own Doctor Who (see "The Doctor meets The Doctor" below).

For obvious reasons, these narratives have always been relegated to the realm of science fiction. But what if – and it is a big what if – you could meet your future self? What a very strange question, but one that I believe is worth asking. (...)

Now, imagine conversing with that future version of you in the same way you might chat with a friend or loved one now. What would you ask? My own knee-jerk response – and that of other people I’ve discussed it with – is often resistance. The source of this, I think, boils down to our desire to see ourselves as unique. How, we wonder, could an algorithm make a prediction about me – me with my many-coloured feathers that make me one in eight billion?

Yet I must accept – grudgingly – that I am not as unique as I like to think, and algorithms already predict my personality, desires and choices on a regular basis. Every time I listen to a personalised Spotify playlist, or love a Netflix film recommendation, a form of AI has predicted it. As these algorithms get more powerful, with greater access to data about us and other similar people, there's no reason they couldn't go beyond surface-level details like your future self's entertainment choices. They might be able to predict how the older, wiser version of you might feel about the decisions in your life.

Eight questions to ask "future you"

So, to return to my original question: if you could time-travel to meet your future self, what aspects of your life would you want to know more about? Which ones would you prefer to be shrouded in secrecy? And if you’d pass up on the meeting, why?

I've been thinking a lot about what I would do. My first instinct would be to ask my future self things like… are you happy? Are your family members happy and healthy? Is the environment safe for your grandkids and great-grandkids?

The more I considered these initial questions, the more I realised just how much I was concerned with what the future holds. A very informal survey of my wife and a few friends suggests I may not be alone in this tendency.

But reflecting on it further, I realised that the most powerful questions would be ones that helped me make better choices today. With that as the goal, I might generate several queries meant to kick off a dialogue between my two selves, such as:

- What have you been most proud of and why?

- In what ways – both positive and negative – have you changed over time?

- What's something that you miss most from earlier in your life?

- What actions have you regretted?

- What actions did you not take that you regret?

- What’s a time period you'd most want to repeat?

- What things should I be paying more attention to now?

- Which things should I stress about a little less?

Imagine if you were to put these eight questions to your future self. What might you find out that would modify how you live now? It’d probably be the most important conversation of your life."

~ Time travel: What if you met your future self? (BBC/Hal Hershfield)

What If Money Expired?

In 995, paper money was introduced in Sichuan, China, when a merchant in Chengdu gave people fancy receipts in exchange for their iron coins. Paper bills spared people the physical burden of their wealth, which helped facilitate trade over longer distances.