Friday, July 31, 2015

Dynasty Trusts: The Permanently Wealthy

It’s a common-sense notion that society’s wealth shouldn’t be governed by ghosts. “Our Creator made the earth for the use of the living and not of the dead,” wrote Thomas Jefferson. (Also: “One generation of men cannot foreclose or burthen its use to another.”) But in our new age of inequality—the top 10 percent now own nearly 80 percent of all wealth—old concerns about wealth and inheritance are coming back from the dead.

Americans have, historically, had a simple approach to dealing with wealth after its holder dies: You can do whatever you want with your property, but not for very long. Rich people can disinherit children. They can put extreme conditions on how their successors can inherit, like requiring marriage. They can build monuments to themselves or give everything to their pets. But they can only do it so long. Eventually, time catches up with them and their estates dissolve.

Or at least that’s how it used to be. Remember that the dead can’t actually do any of this themselves because they are, in fact, dead. Instead, a trust is empowered to carry out the last wishes of the deceased. A trust is simply a legal entity that contains property; people tell a trust what they want to do, and the trust acts like a ghost, enforcing their wishes beyond the grave. But there’s a safeguard built in to prevent abuses: Trusts have been governed by something called the rule against perpetuities, which places a roughly 100-year limit on how long they can exist. This prevents people with no connection to the living world from putting restrictions on our country’s wealth.

In recent years, the safeguard of time has been eroded. As the tax expert Ray D. Madoff documents in her 2010 book Immortality and the Law: The Rising Power of the American Dead, we are experiencing a rapid rise of dynasty trusts, which massively expand the power of the dead over the wealth of the living.

To take advantage of a change made to the tax code in the 1980s, states started to radically diminish or outright remove the rule against perpetuities in the 1990s. This resulted in a race to the bottom, with states competing to see which could most effectively restructure their laws to benefit the rich. By 2003, states weakening these rules received an estimated $100 billion in additional trust business. Now, 28 states allow trusts to live indefinitely, or nearly so, creating what are called perpetual dynasty trusts.

Since they’re designed to live forever, dynasty trusts can engage in more controlling long-term activities than normal trusts, which are designed to have an end. Dynasty trusts can also avoid taxes for the term of the trust. A generous multimillion-dollar tax exemption for trusts that skip a generation can be leveraged aggressively. And since the eventual death of the trust isn’t built in, a dynasty trust can buy houses and assets that are retained for descendants, tax-free, by the trust indefinitely. The wealthy can tie up their money, outside of any public obligation or scrutiny, forever.

by Mike Konczal, The Nation | Read more:

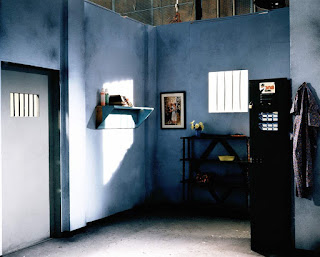

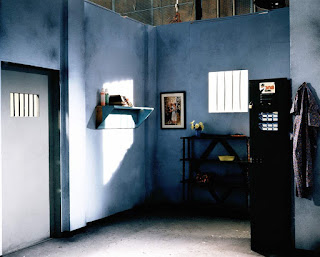

Image: Tracy Loeffelholz Dunn

Seattle's $87.6 Million Dollar Man

[ed. I love Russell Wilson, but... wow. I hope this doesn't compromise contract negotiations for any of the other great players on the team.]

But the Seahawks have reached an agreement on a contract extension with quarterback Russell Wilson this morning, shortly before the team is to begin training camp at the VMAC in Renton, preparing for the 2015 season — and when Wilson’s side had set a deadline to get the deal done or play the season without an extension. Wilson confirmed the news via Twitter.

The contract is said to be a four-year extension worth $87.6 million, according to Peter King of Sports Illustrated, who first had the news.

It is said to include a $31 million signing bonus with $60 million guaranteed. The guaranteed money had been regarded as one of the prime sticking points in the negotiations. That is more than the $54 million guaranteed of Green Bay’s Aaron Rodgers, whose contract is for $22 million a year, a little more than the $21.9 million of Wilson.

While the average per year is about what it had been said Wilson had been offered all along, the guarantee is higher than a source said the team had initially been offering, and it was that increase that appears to have allowed the deal to get done.

Wilson was entering the final season of his initial four-year rookie contract which would have paid him $1.52 million in 2015.

by Bob Condotta, Seattle Times | Read more:

Image: Wikipedia

Thursday, July 30, 2015

Power in Numbers

The best historical analogy for the ‘‘hackathon’’ might be the 18th-century custom of the barn-raising. Despite the technological abyss separating the two rituals, they are structurally akin: Each is a social observance in which a lot of people focus their collective will on an undertaking too great for any individual to carry out alone. Though the informal practice of hackathons arose slightly earlier, the first use of the portmanteau name dates to 1999, when Sun Microsystems and the freeware operating system OpenBSD each staged events under that banner to write very specialized pieces of software very quickly.

Over time, the sense of the term has expanded; one count estimates that in 2015 there will be more than 1,500 gatherings branded as hackathons, with this summer alone offering events designed to plan for Australia’s aging population, conserve water in India and streamline the resale of tickets at Wimbledon. There are hackathons for television technologies, life sciences and political causes — the term these days is used anywhere people congregate with the expectation of getting something vaguely machine-oriented done in one big room.

The world’s largest recurring convention of people and their machines is DreamHack, a 72-hour rally that takes place twice a year in the convention center in Jonkoping, Sweden, a lake city about 200 miles southwest of Stockholm. The most recent jamboree hosted more than 23,000 people from at least 55 nations and every inhabited continent; on their 9,500 computers (as well as 14,000 other network-connected devices), the attendees made up what organizers believe to be the largest impromptu LAN, or local area network, assembled anywhere.

DreamHack began in 1994, in the basement of a nearby elementary school, as a small, local subvariant of what was then called a ‘‘copyparty’’ — pre-broadband occasions to share software or demonstrate flashy off-label uses of early home computers. As the event has grown, its enormous ad hoc network has been given over largely to gaming; for far-flung clans of four or five teammates, this can be the only chance they get all year to palaver in person. But participants also use the LAN to collaborate on all manner of projects, from songs to films to digital artworks, all of which are presented to the crowd.

by Gideon Lewis-Kraus, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Franck BohbotWindows 10 is the Best Version Yet—Once the Bugs Get Fixed

I'm more conflicted about Windows 10 than I have been about any previous version of Windows. In some ways, the operating system is extremely ambitious; in others, it represents a great loss of ambition. The new release tries to walk an unsteady path between being Microsoft's most progressive, forward-looking release and simultaneously appealing to Windows' most conservative users.

And it mostly succeeds, making this the best version of Windows yet—once everything's working. In its current form, the operating system doesn't feel quite finished, and I'd wait a few weeks before making the leap.

Windows 7 was a straightforward proposition, a testament to the power of a new name. Windows Vista may have had a poor reputation, but it was a solid operating system. Give hardware and software vendors three years to develop drivers, come to grips with security changes, fix a few bugs, and freeze the hardware requirements, and the result was Windows 7—an operating system that worked with almost any hardware, almost any software. It was comfortable and familiar. Add some small but desirable enhancements to window management and the task bar, and the result was a hugely popular operating system, the high point of the entire Windows family's development.

Windows 7 was a straightforward proposition, a testament to the power of a new name. Windows Vista may have had a poor reputation, but it was a solid operating system. Give hardware and software vendors three years to develop drivers, come to grips with security changes, fix a few bugs, and freeze the hardware requirements, and the result was Windows 7—an operating system that worked with almost any hardware, almost any software. It was comfortable and familiar. Add some small but desirable enhancements to window management and the task bar, and the result was a hugely popular operating system, the high point of the entire Windows family's development.

Windows 8 was similarly easy to understand. With it, Microsoft wanted to make Windows work well on tablets while also wanting an operating system that continued to support the enormous legacy of Win32 applications.

Windows 8 did both of these things—just not at the same time. It contained the basics of a very competent tablet platform, with particularly strong handling of multitasking. It also contained, in most regards, a solid desktop operating system that was very similar to Windows 7. Some things it even made a little better; in Windows 8, for instance, the taskbar finally became multi-monitor aware, ending the need for various third-party hacks.

But these worlds collided in an ugly fashion. The tablet part was never self-contained, with touch users forced to visit finger-unfriendly desktop apps to access a full range of system settings, manage files, and so on. And many desktop users resented being forced to use a full-screen application launcher that, while perfectly functional, was clearly designed for touch users first.

This operating system showcased some of Microsoft's worst habits. Windows has always been a frustratingly inconsistent platform, sporting a mix not just of visual styles but also of user interface elements. It contains, for example, multiple different styles of "menu." While these all do roughly the same thing, they differ both in how they look and in some of the finer points of their behavior. Windows 8 introduced yet another new and very different appearance and set of interface elements to Windows, with no effort to unify and integrate. (...)

Since Windows 8's launch, touch PCs have proliferated, and while there was some initially awkward experimentation, manufacturers today have a decent idea of how to do touch systems. While there's still some skepticism about the value of touch on a desktop PC, on laptops it's an attractive feature, especially when paired with perhaps the best form factor innovation that has come from the Windows 8 experimentation: the 360-degree hinge. As an occasional business traveler sitting in misery in cattle class, the ability to use a laptop in "stand" mode or "tent" mode for watching movies is genuinely useful. Touch makes it practical.

Similarly, devices such as Microsoft's own Surface Pro 3 have found a small but growing audience. Its combination of touch, pen, and keyboard has won plaudits, and, while it's still early days, it looks as if Microsoft is starting to build a small but credible PC hardware business.

Which all means that Microsoft's broad desire with Windows 8 was perhaps not entirely off-base. Touch systems are not some discrete category entirely disjointed from more traditional machines. Rather, there's a continuum of devices, ranging from the dedicated mouse-and-keyboard machine through to the tablet that may occasionally be paired with a Bluetooth keyboard and all the way on to the smartphone, which will almost never use anything but touch. Microsoft continues to want to make Windows an operating system that works across this spectrum—and the dream lives on in Windows 10.

And it mostly succeeds, making this the best version of Windows yet—once everything's working. In its current form, the operating system doesn't feel quite finished, and I'd wait a few weeks before making the leap.

Windows 7 was a straightforward proposition, a testament to the power of a new name. Windows Vista may have had a poor reputation, but it was a solid operating system. Give hardware and software vendors three years to develop drivers, come to grips with security changes, fix a few bugs, and freeze the hardware requirements, and the result was Windows 7—an operating system that worked with almost any hardware, almost any software. It was comfortable and familiar. Add some small but desirable enhancements to window management and the task bar, and the result was a hugely popular operating system, the high point of the entire Windows family's development.

Windows 7 was a straightforward proposition, a testament to the power of a new name. Windows Vista may have had a poor reputation, but it was a solid operating system. Give hardware and software vendors three years to develop drivers, come to grips with security changes, fix a few bugs, and freeze the hardware requirements, and the result was Windows 7—an operating system that worked with almost any hardware, almost any software. It was comfortable and familiar. Add some small but desirable enhancements to window management and the task bar, and the result was a hugely popular operating system, the high point of the entire Windows family's development.Windows 8 was similarly easy to understand. With it, Microsoft wanted to make Windows work well on tablets while also wanting an operating system that continued to support the enormous legacy of Win32 applications.

Windows 8 did both of these things—just not at the same time. It contained the basics of a very competent tablet platform, with particularly strong handling of multitasking. It also contained, in most regards, a solid desktop operating system that was very similar to Windows 7. Some things it even made a little better; in Windows 8, for instance, the taskbar finally became multi-monitor aware, ending the need for various third-party hacks.

But these worlds collided in an ugly fashion. The tablet part was never self-contained, with touch users forced to visit finger-unfriendly desktop apps to access a full range of system settings, manage files, and so on. And many desktop users resented being forced to use a full-screen application launcher that, while perfectly functional, was clearly designed for touch users first.

This operating system showcased some of Microsoft's worst habits. Windows has always been a frustratingly inconsistent platform, sporting a mix not just of visual styles but also of user interface elements. It contains, for example, multiple different styles of "menu." While these all do roughly the same thing, they differ both in how they look and in some of the finer points of their behavior. Windows 8 introduced yet another new and very different appearance and set of interface elements to Windows, with no effort to unify and integrate. (...)

Since Windows 8's launch, touch PCs have proliferated, and while there was some initially awkward experimentation, manufacturers today have a decent idea of how to do touch systems. While there's still some skepticism about the value of touch on a desktop PC, on laptops it's an attractive feature, especially when paired with perhaps the best form factor innovation that has come from the Windows 8 experimentation: the 360-degree hinge. As an occasional business traveler sitting in misery in cattle class, the ability to use a laptop in "stand" mode or "tent" mode for watching movies is genuinely useful. Touch makes it practical.

Similarly, devices such as Microsoft's own Surface Pro 3 have found a small but growing audience. Its combination of touch, pen, and keyboard has won plaudits, and, while it's still early days, it looks as if Microsoft is starting to build a small but credible PC hardware business.

Which all means that Microsoft's broad desire with Windows 8 was perhaps not entirely off-base. Touch systems are not some discrete category entirely disjointed from more traditional machines. Rather, there's a continuum of devices, ranging from the dedicated mouse-and-keyboard machine through to the tablet that may occasionally be paired with a Bluetooth keyboard and all the way on to the smartphone, which will almost never use anything but touch. Microsoft continues to want to make Windows an operating system that works across this spectrum—and the dream lives on in Windows 10.

by Peter Bright, Ars Technica | Read more:

Image: Andrew CunninghamWednesday, July 29, 2015

Taking It Slow, Until She Took Charge

They didn’t plan for things to turn out this way: both of them well past 50, both living with a parent in the houses they grew up in, never married, no children. Most people don’t.

They thought, growing up where Brooklyn is more snug suburb than freewheeling city, that there would be romance, weddings, independence. She thought she would marry a man she met while working for the Coast Guard, but he was transferred to Los Angeles. He thought he might settle down with a woman who worked at the pharmacy around a decade ago, but a jealous ex-husband got in the way.

Even now, after decades of waiting, Ann Iervolino, 57, and Peter Cipolla, 58, are learning patience.

Even now, after decades of waiting, Ann Iervolino, 57, and Peter Cipolla, 58, are learning patience.

But love is no less sweet for coming to them late.

Summer 2007: On weekends or after work at American Express, where Ms. Iervolino was an auditor, she would ride her bike from her house in Homecrest, Brooklyn, over to Marine Park, where a swirl of young men blurred the basketball courts and those for whom life had slowed down tarried at the bocce courts. She would stop to chat with a few friends, the wives of the bocce players. Mr. Cipolla would be sitting there on a bench in shorts and a white T-shirt, close-cropped hair paling, a man of no particular outward distinction except that he was the youngest around.

She thought he was a sanitation worker. Then she thought, “Gee, he must be married, and I’m not looking to fool around.”

Not that she was looking for somebody. And anyway, he never talked to her, just sat there watching the balls hop and skid. After long days of work at a Long Island lab, it was his time for letting his mind empty out.

But when she failed to appear a few days running, “I’d say, Where’s the girl on the bike? I don’t know — she had nice legs. I like athleticism,” he explained, in his slow, earnest way. She was good-looking. Dark and petite. Nice body. A good head on her shoulders.

“You know, Ann,” said Terry, one of the park regulars, “you and Peter have a lot in common. You guys should talk.”

The list of parallels was short, pared down to the essentials. They were both single. Both never married. Both taking care of an aging parent. Both Italian.

“Just those things alone,” Terry predicted, “you could probably be in tune with each other.”

The advice fell on skeptical ears. “He’s so frickin’ shy that he doesn’t talk to me,” Ms. Iervolino retorted.

Eight years later, Mr. Cipolla was explaining himself over egg creams. “I’m methodical,” he said recently at the Floridian Diner in Marine Park. “I’m analytical.” She had finished her egg cream in short, deft slurps; his straw was still half-submerged.

He hit on a secret scheme — and, it must be acknowledged, an awfully slow one — for helping things along. She wanted to watch Larry David on “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” but she did not have HBO. She surveyed the Marine Park Bocce Club: Could anyone record it for her?

He volunteered to tape every episode on VHS every Sunday night. He would call her and say, “Ann, is it on HBO or HBO West?” He didn’t need to know. He just wanted to call her. (...)

In September, Ms. Iervolino went by herself to the bocce club’s annual dinner, where she danced with Vito, with Vinny, with Ben.

The others missed nothing. Word on the bocce court was that “Ann was dancing up a storm with these older gentlemen, that Vito really liked her,” Mr. Cipolla recalled. “I didn’t get jealous, but I got a little hot under the collar. I move like a snail.”

He had the advantage in age, he consoled himself. In money. In education. He had a doctorate in forensic anthropology from St. John’s University. “I said, I could beat him out.”

Ms. Iervolino protests to this day that Vito was never in the picture. “Vito’s a nicer, older gentleman,” she said calmly. “He was very cordial. But I don’t want somebody old. I’m not Anna Nicole Smith.”

Even so, things advanced sluggishly. By October, Larry David was off the air, and still no official declarations had been made.

“Now what do I do?” Mr. Cipolla said. “I have to get flowers. I can’t just get any flowers. I go to Marine Florists. They ask, ‘Who are they for?’ I say, ‘A potential girlfriend.’ ”

They asked what he wanted to write on the card.

“I’ve got to remember the saying,” she said at this point in the retelling, though one suspects it would be difficult to forget what he wrote: “I thought I had everything,” the card said, “and then I met you.”

They thought, growing up where Brooklyn is more snug suburb than freewheeling city, that there would be romance, weddings, independence. She thought she would marry a man she met while working for the Coast Guard, but he was transferred to Los Angeles. He thought he might settle down with a woman who worked at the pharmacy around a decade ago, but a jealous ex-husband got in the way.

Even now, after decades of waiting, Ann Iervolino, 57, and Peter Cipolla, 58, are learning patience.

Even now, after decades of waiting, Ann Iervolino, 57, and Peter Cipolla, 58, are learning patience.But love is no less sweet for coming to them late.

Summer 2007: On weekends or after work at American Express, where Ms. Iervolino was an auditor, she would ride her bike from her house in Homecrest, Brooklyn, over to Marine Park, where a swirl of young men blurred the basketball courts and those for whom life had slowed down tarried at the bocce courts. She would stop to chat with a few friends, the wives of the bocce players. Mr. Cipolla would be sitting there on a bench in shorts and a white T-shirt, close-cropped hair paling, a man of no particular outward distinction except that he was the youngest around.

She thought he was a sanitation worker. Then she thought, “Gee, he must be married, and I’m not looking to fool around.”

Not that she was looking for somebody. And anyway, he never talked to her, just sat there watching the balls hop and skid. After long days of work at a Long Island lab, it was his time for letting his mind empty out.

But when she failed to appear a few days running, “I’d say, Where’s the girl on the bike? I don’t know — she had nice legs. I like athleticism,” he explained, in his slow, earnest way. She was good-looking. Dark and petite. Nice body. A good head on her shoulders.

“You know, Ann,” said Terry, one of the park regulars, “you and Peter have a lot in common. You guys should talk.”

The list of parallels was short, pared down to the essentials. They were both single. Both never married. Both taking care of an aging parent. Both Italian.

“Just those things alone,” Terry predicted, “you could probably be in tune with each other.”

The advice fell on skeptical ears. “He’s so frickin’ shy that he doesn’t talk to me,” Ms. Iervolino retorted.

Eight years later, Mr. Cipolla was explaining himself over egg creams. “I’m methodical,” he said recently at the Floridian Diner in Marine Park. “I’m analytical.” She had finished her egg cream in short, deft slurps; his straw was still half-submerged.

He hit on a secret scheme — and, it must be acknowledged, an awfully slow one — for helping things along. She wanted to watch Larry David on “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” but she did not have HBO. She surveyed the Marine Park Bocce Club: Could anyone record it for her?

He volunteered to tape every episode on VHS every Sunday night. He would call her and say, “Ann, is it on HBO or HBO West?” He didn’t need to know. He just wanted to call her. (...)

In September, Ms. Iervolino went by herself to the bocce club’s annual dinner, where she danced with Vito, with Vinny, with Ben.

The others missed nothing. Word on the bocce court was that “Ann was dancing up a storm with these older gentlemen, that Vito really liked her,” Mr. Cipolla recalled. “I didn’t get jealous, but I got a little hot under the collar. I move like a snail.”

He had the advantage in age, he consoled himself. In money. In education. He had a doctorate in forensic anthropology from St. John’s University. “I said, I could beat him out.”

Ms. Iervolino protests to this day that Vito was never in the picture. “Vito’s a nicer, older gentleman,” she said calmly. “He was very cordial. But I don’t want somebody old. I’m not Anna Nicole Smith.”

Even so, things advanced sluggishly. By October, Larry David was off the air, and still no official declarations had been made.

“Now what do I do?” Mr. Cipolla said. “I have to get flowers. I can’t just get any flowers. I go to Marine Florists. They ask, ‘Who are they for?’ I say, ‘A potential girlfriend.’ ”

They asked what he wanted to write on the card.

“I’ve got to remember the saying,” she said at this point in the retelling, though one suspects it would be difficult to forget what he wrote: “I thought I had everything,” the card said, “and then I met you.”

by Vivian Yee, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Damon Winter

Tuesday, July 28, 2015

Somehow Teen Girls Get the Coolest Wearable Out There

Jewelbots are bracelets with programmable plastic flowers made for middle-school girls. They’re also the most interesting wearable I’ve seen this year.

Their creators describe them as “friendships bracelets that teach girls to code.” Compared to a gleaming Apple Watch or even an entry-level Fitbit, the Jewelbot hardware is primitive: a semi-translucent plastic flower charm that slides onto a hair tie–like elastic bracelet. The functionality is basic, too. The charms talk to each other over Bluetooth, and using a Jewelbots smartphone app, youngsters can program their charms to vibrate or light up when their friends are nearby. But despite their apparent simplicity, Jewelbots exhibit some truly fresh thinking about wearable technology. And with a little imagination, they hint at devices far more interesting than today’s computer watches.

Jewelbots was co-founded by Sara Chipps, Brooke Moreland, and Maria Paula Saba. Chipps is a developer and co-founder of Girl Develop It, a nonprofit that teaches women to code. Moreland is an entrepreneur with experience in high-tech fashion products, and Saba is a graduate of NYU’s ITP program, now studying Bluetooth and Arduino as a post-doc fellow. But before Jewelbots was a product, it was a shared ambition. More than any particular feature or function, the group wanted to build something that would get teenage girls interested in programming.

Jewelbots was co-founded by Sara Chipps, Brooke Moreland, and Maria Paula Saba. Chipps is a developer and co-founder of Girl Develop It, a nonprofit that teaches women to code. Moreland is an entrepreneur with experience in high-tech fashion products, and Saba is a graduate of NYU’s ITP program, now studying Bluetooth and Arduino as a post-doc fellow. But before Jewelbots was a product, it was a shared ambition. More than any particular feature or function, the group wanted to build something that would get teenage girls interested in programming.

The idea took shape over several years. The group started by looking at products like MySpace and Minecraft that had successfully enticed kids to dabble in code. “We kind of wanted to reverse engineer that,” Chipps says. These examples were reassuring. They proved that if kids are genuinely interested in an outcome or effect—building a unique Minecraft structure, say, or tricking out their Myspace profiles—they won’t shy away from code as a means to achieve it.

That just left the question of the desired effect. Initially, the creators imagined Jewelbots as digital ornament that could be programmed to match girls’ outfits. But the verdict from talking to prospective preteen users was negative. “They were like,’That sounds really stupid, and I would never use that,'” Chipps says. Instead, the girls always returned to two themes: friendship and communication.

The enmities and allegiances that form and dissolve in a single day rival anything that might be taught in European history class. Teens and preteens crave ways to make these connections visible.

This isn’t surprising. As the Jewelbots founders were reminded by company adviser Amy Jo Kim, a longtime researcher of online communities, middle school is an age where everyone is tribal. The enmities and allegiances that form and dissolve in a single day rival anything that might be taught in European history class. What’s more, teens and preteens crave ways to make these connections visible. That settled things. Where other wearables had sought to reinvent the watch, Jewelbots followed a different template: the friendship bracelet.

Using the Jewelbots smartphone app, a girl can assign a friend one of eight different colors. When they’re nearby, both of their charms light up that color. They can assign other friends to other colors; if they’re hanging out in a group, all their Jewelbots bangles turn into pulsing rainbow flair. The charm also doubles as a button which can be used to send haptic messages to friends in a particular color group (the message presumably drafted in accordance with a phenomenally complex code developed by the cohort at an earlier time.) All these features are set up through a smartphone app, but the Jewelbots stay connected through a Bluetooth mesh network, independent of Wi-Fi or cell towers. “The way we designed it is that girls never need their phones,” Chipps says.

There’s much more Jewelbots can do if girls care to figure it out. The smartphone app is meant to be a simple point of entry, but by plugging their charm into their computer, girls can use Arduino software to hook up their Jewelbots to just about anything. Maybe someone wants hers to glow green every time she gets a new follower on Instagram, or to vibrate when her dog leaves the yard. Both possible, and totally doable for a novice coder, Chipps says. With this more advanced use, the Jewelbot becomes a personal node linked up to the greater world of open-source hardware and software. “That’s where we’re really hoping to drive the girls,” Chipps says.

Jewelbots are a thoughtfully constructed Trojan Horse for getting young girls to think about programming. The company’s Kickstarter campaign has raised $90,000. But the bracelets might also have worthwhile lessons for other wearable makers.

Their creators describe them as “friendships bracelets that teach girls to code.” Compared to a gleaming Apple Watch or even an entry-level Fitbit, the Jewelbot hardware is primitive: a semi-translucent plastic flower charm that slides onto a hair tie–like elastic bracelet. The functionality is basic, too. The charms talk to each other over Bluetooth, and using a Jewelbots smartphone app, youngsters can program their charms to vibrate or light up when their friends are nearby. But despite their apparent simplicity, Jewelbots exhibit some truly fresh thinking about wearable technology. And with a little imagination, they hint at devices far more interesting than today’s computer watches.

Jewelbots was co-founded by Sara Chipps, Brooke Moreland, and Maria Paula Saba. Chipps is a developer and co-founder of Girl Develop It, a nonprofit that teaches women to code. Moreland is an entrepreneur with experience in high-tech fashion products, and Saba is a graduate of NYU’s ITP program, now studying Bluetooth and Arduino as a post-doc fellow. But before Jewelbots was a product, it was a shared ambition. More than any particular feature or function, the group wanted to build something that would get teenage girls interested in programming.

Jewelbots was co-founded by Sara Chipps, Brooke Moreland, and Maria Paula Saba. Chipps is a developer and co-founder of Girl Develop It, a nonprofit that teaches women to code. Moreland is an entrepreneur with experience in high-tech fashion products, and Saba is a graduate of NYU’s ITP program, now studying Bluetooth and Arduino as a post-doc fellow. But before Jewelbots was a product, it was a shared ambition. More than any particular feature or function, the group wanted to build something that would get teenage girls interested in programming.The idea took shape over several years. The group started by looking at products like MySpace and Minecraft that had successfully enticed kids to dabble in code. “We kind of wanted to reverse engineer that,” Chipps says. These examples were reassuring. They proved that if kids are genuinely interested in an outcome or effect—building a unique Minecraft structure, say, or tricking out their Myspace profiles—they won’t shy away from code as a means to achieve it.

That just left the question of the desired effect. Initially, the creators imagined Jewelbots as digital ornament that could be programmed to match girls’ outfits. But the verdict from talking to prospective preteen users was negative. “They were like,’That sounds really stupid, and I would never use that,'” Chipps says. Instead, the girls always returned to two themes: friendship and communication.

The enmities and allegiances that form and dissolve in a single day rival anything that might be taught in European history class. Teens and preteens crave ways to make these connections visible.

This isn’t surprising. As the Jewelbots founders were reminded by company adviser Amy Jo Kim, a longtime researcher of online communities, middle school is an age where everyone is tribal. The enmities and allegiances that form and dissolve in a single day rival anything that might be taught in European history class. What’s more, teens and preteens crave ways to make these connections visible. That settled things. Where other wearables had sought to reinvent the watch, Jewelbots followed a different template: the friendship bracelet.

Using the Jewelbots smartphone app, a girl can assign a friend one of eight different colors. When they’re nearby, both of their charms light up that color. They can assign other friends to other colors; if they’re hanging out in a group, all their Jewelbots bangles turn into pulsing rainbow flair. The charm also doubles as a button which can be used to send haptic messages to friends in a particular color group (the message presumably drafted in accordance with a phenomenally complex code developed by the cohort at an earlier time.) All these features are set up through a smartphone app, but the Jewelbots stay connected through a Bluetooth mesh network, independent of Wi-Fi or cell towers. “The way we designed it is that girls never need their phones,” Chipps says.

There’s much more Jewelbots can do if girls care to figure it out. The smartphone app is meant to be a simple point of entry, but by plugging their charm into their computer, girls can use Arduino software to hook up their Jewelbots to just about anything. Maybe someone wants hers to glow green every time she gets a new follower on Instagram, or to vibrate when her dog leaves the yard. Both possible, and totally doable for a novice coder, Chipps says. With this more advanced use, the Jewelbot becomes a personal node linked up to the greater world of open-source hardware and software. “That’s where we’re really hoping to drive the girls,” Chipps says.

Jewelbots are a thoughtfully constructed Trojan Horse for getting young girls to think about programming. The company’s Kickstarter campaign has raised $90,000. But the bracelets might also have worthwhile lessons for other wearable makers.

by Kyle Vanhemert, Wired | Read more:

Image: Jewelbots

Patriots QB Tom Brady Has Only Himself to Blame

Up front, long before the air started hissing out of his charmed world, Tom Brady should have taken a knee. He should have confessed his venial football sin and admitted to everyone that his never-ending pursuit of a competitive edge got the better of him.

OK, so maybe he should have waited to confess until sometime after the Super Bowl, just in case Roger Goodell had it in him to bench the big star for the big game. But either way, Brady should have come clean about the improper deflation of his AFC Championship Game footballs and then banked on the American public's unbreakable ability to forgive and (pretty much) forget.

Although he enjoys top-of-the-line legal representation and his lawyers will file a brilliantly written lawsuit, Tom Brady's effort to stop his suspension is doomed.

Although he enjoys top-of-the-line legal representation and his lawyers will file a brilliantly written lawsuit, Tom Brady's effort to stop his suspension is doomed.

Many teams, players, coaches and executives have run afoul of the NFL's rules. Check out the most recent examples here.

Alex Rodriguez disgraced himself and his sport in ways Brady never has and never will, and now there are millions of New Yorkers itching to throw the revived and allegedly reformed slugger a parade. Did one of the two greatest quarterbacks of all time really believe his standing among New England Patriots fans -- and among neutral observers worldwide who simply appreciate self-made masters of their trade -- couldn't survive the plain truth about Deflategate?

Bill Belichick survived Spygate; he's up there with Vince Lombardi among the all-timers. Brady is up there with his idol, Joe Montana, and his decision to destroy a cell phone that likely implicated him in a low-rent scheme with two team flunkies doesn't destroy his legacy as a four-time champ.

But it does make Brady look like a liar. A liar in this case, anyway. In announcing his ruling to uphold Brady's four-game suspension, Goodell said the quarterback had his personal assistant do an end zone dance on his phone on or around the same March day Brady met with the investigators who already had asked to see relevant texts and emails on that phone.

Brady didn't reveal he'd effectively deleted nearly 10,000 texts over a four-month period until days before his 10-hour appeal hearing on June 23. According to the NFL ruling, he said the destruction of old cell phones was merely a part of his normal routine, like warming up with Julian Edelman and Gronk. But on page 12 of Goodell's 20-page decision, the commissioner points out that the phone Brady used before the one in question was intact and available for a forensic expert to review. "No explanation was provided for this anomaly," Goodell wrote.![]() Tom Brady missed an opportunity to save face -- and he has only himself to blame.

Tom Brady missed an opportunity to save face -- and he has only himself to blame.

Brady hasn't offered a credible explanation in this case from the start, and for good reason: He doesn't have one. The Ted Wells probe turned up enough circumstantial evidence for a common-sense, agenda-free reader to conclude what Montana and Troy Aikman and their combined seven rings and two Hall of Fame busts concluded in the early hours of this mess: Brady had to have known what those two Patriots staffers, or Watergate burglars, were doing to his footballs.

Goodell cited Brady's quarterback-room meeting and numerous cell-phone conversations with John Jastremski after the allegations surfaced; the quarterback had no such meeting or conversations with the equipment assistant during the regular season. Jim McNally, the officials' locker room attendant and the man believed to have taken a 100-second bathroom break with New England's AFC Championship Game balls, also makes a return appearance in the commissioner's decision as the self-described "Deflator."

Of course, we already knew about Jastremski and McNally. We also knew that Wells had offered to allow Brady's agent to screen his phone before turning over texts and emails to investigators, and that Goodell's lieutenant, Troy Vincent, had noted in the May announcement of the quarterback's suspension his refusal to cooperate despite "extraordinary safeguards by the investigators to protect unrelated personal information."

We didn't know Brady had crushed the phone in question like, you know, he'd crushed the Indianapolis Colts.

by Ian O'Connor, ESPN | Read more:

Image: via:

OK, so maybe he should have waited to confess until sometime after the Super Bowl, just in case Roger Goodell had it in him to bench the big star for the big game. But either way, Brady should have come clean about the improper deflation of his AFC Championship Game footballs and then banked on the American public's unbreakable ability to forgive and (pretty much) forget.

Although he enjoys top-of-the-line legal representation and his lawyers will file a brilliantly written lawsuit, Tom Brady's effort to stop his suspension is doomed.

Although he enjoys top-of-the-line legal representation and his lawyers will file a brilliantly written lawsuit, Tom Brady's effort to stop his suspension is doomed.Many teams, players, coaches and executives have run afoul of the NFL's rules. Check out the most recent examples here.

Alex Rodriguez disgraced himself and his sport in ways Brady never has and never will, and now there are millions of New Yorkers itching to throw the revived and allegedly reformed slugger a parade. Did one of the two greatest quarterbacks of all time really believe his standing among New England Patriots fans -- and among neutral observers worldwide who simply appreciate self-made masters of their trade -- couldn't survive the plain truth about Deflategate?

Bill Belichick survived Spygate; he's up there with Vince Lombardi among the all-timers. Brady is up there with his idol, Joe Montana, and his decision to destroy a cell phone that likely implicated him in a low-rent scheme with two team flunkies doesn't destroy his legacy as a four-time champ.

But it does make Brady look like a liar. A liar in this case, anyway. In announcing his ruling to uphold Brady's four-game suspension, Goodell said the quarterback had his personal assistant do an end zone dance on his phone on or around the same March day Brady met with the investigators who already had asked to see relevant texts and emails on that phone.

Brady didn't reveal he'd effectively deleted nearly 10,000 texts over a four-month period until days before his 10-hour appeal hearing on June 23. According to the NFL ruling, he said the destruction of old cell phones was merely a part of his normal routine, like warming up with Julian Edelman and Gronk. But on page 12 of Goodell's 20-page decision, the commissioner points out that the phone Brady used before the one in question was intact and available for a forensic expert to review. "No explanation was provided for this anomaly," Goodell wrote.

Brady hasn't offered a credible explanation in this case from the start, and for good reason: He doesn't have one. The Ted Wells probe turned up enough circumstantial evidence for a common-sense, agenda-free reader to conclude what Montana and Troy Aikman and their combined seven rings and two Hall of Fame busts concluded in the early hours of this mess: Brady had to have known what those two Patriots staffers, or Watergate burglars, were doing to his footballs.

Goodell cited Brady's quarterback-room meeting and numerous cell-phone conversations with John Jastremski after the allegations surfaced; the quarterback had no such meeting or conversations with the equipment assistant during the regular season. Jim McNally, the officials' locker room attendant and the man believed to have taken a 100-second bathroom break with New England's AFC Championship Game balls, also makes a return appearance in the commissioner's decision as the self-described "Deflator."

Of course, we already knew about Jastremski and McNally. We also knew that Wells had offered to allow Brady's agent to screen his phone before turning over texts and emails to investigators, and that Goodell's lieutenant, Troy Vincent, had noted in the May announcement of the quarterback's suspension his refusal to cooperate despite "extraordinary safeguards by the investigators to protect unrelated personal information."

We didn't know Brady had crushed the phone in question like, you know, he'd crushed the Indianapolis Colts.

Image: via:

Less Money, Mo' Music & Lots of Problems: A Look at the Music Biz

The disruption of the music industry has undoubtedly benefited consumers, but for many on the inside, its consequences have been both profound and painful. Artists finally have direct connections to their audiences, but they must fight through more noise than ever before. Distribution is no longer constrained by shelf space or A&R men, but a stream or download generates royalties many artists decry as untenable. Audiences can now enjoy more music, more easily and in more places – yet the amount they spend is at an unprecedented low.

Music may have been the first media format to be upended by digital, but it remains deeply challenged even as video, publishing and gaming continue their path forward (however modestly). If the industry hopes to restore growth and fix the problems with today’s streaming models, it needs to confront its evolution: how have ecosystem revenues – from albums sales to concerts, radio plays, digital downloads and streams – changed and been redistributed? What is the underlying value of music? Did streaming erode this value or correct it? What’s the logic behind streaming royalty models and where are its flaws and decencies? How can it be improved? After 15 years of declining consumer spend, it’s time to stop focusing on what was or “should” be. Industries don’t rebuild themselves.

PART I: HOW WE GOT HERE:

The Decline of Recorded Music Sales

Since the RIAA began its comprehensive database of US music sales in 1973, the category has never commanded less in consumer spend than it does today. On an inflation-adjusted basis, sales have plummeted by over 70% (or $14B) since 1999 – even though the American population has grown by some 46M over the period. And this decline is likely to continue. Digital revenues have begun to fall and CDs, which still represent 30% of sales, are unlikely to rebound. In Q3 of 2014, Wal-Mart, which moves one in every four physical discs sold in the United States, nearly halved the shelf space dedicated to the format, as well as the number of unique records it carried. In a few years, Amazon may be the only mass market retailer of physical music, at which point prices will undoubtedly tumble further.

What makes this decline particularly controversial is the fact that consumption of recorded music is greater than ever before. We listen to it wherever we go: on the subway, waiting in line, getting groceries and anywhere else we can. The soundtracks of our lives, so to speak, rarely stop. As a result, music executives often blame the collapse of revenues on iTunes’ 99¢ price points (and claim that the associated deal they struck with Apple arose only out of the extraordinary paranoia and confusion surrounding digital distribution and piracy in the early 2000s). However, much of the industry’s pre-iTunes value was inflated, held up only by bundle-based packaging (viz. albums), rather than consumer demand. Per track prices mattered, of course, but they’re also a distraction.

The End of the Age of Ownership: First Albums, then Tracks

The introduction of true a la carte music purchasing was bound to disrupt the music business. Everyone knew the album model had forced consumers to “own” tracks they didn’t want and prevented them from owning some of those they did, but how this would net out was impossible to predict. Nearly 15 years later, however, the answer has become clear.

By 2010, the total number of tracks (including album track equivalents) sold in the United States each year had fallen by 57% (to roughly 4.6B). Though it’s convenient to blame piracy, NPD estimates that fewer than 340M tracks were pirated in the United States in 2010 (~17M pirates downloading an average of 20 tracks each). Even if every one of these illegal downloads represented a cannibalized sale, the industry would still be down more than 50%. The same is true if the number of pirated tracks were somehow twice as many as NPD had estimated. With fewer than 1.5M Americans subscribed to music streaming services in 2010, this explanation also falls short. The end of the album didn’t just bring about the end of unearned revenues, it revealed that the underlying demand for “owned” music was much lower than most believed. Recognizing this fact is critical. If the music industry hopes to increase sales and better support its artists, revenues will need to be generated outside of conventional unit sales.

But first, it’s also important to note that the album-to-track conversion has been doubly bad for the most popular artists. In the album days, consumer spend was monopolized by a handful of $20 “must have” records released by the Beatles and Michael Jacksons of the world. Today, that same spend (or what’s left of it) can be spread across dozens of artists – with each one compensated only for the specific tracks a consumer picks.

Music may have been the first media format to be upended by digital, but it remains deeply challenged even as video, publishing and gaming continue their path forward (however modestly). If the industry hopes to restore growth and fix the problems with today’s streaming models, it needs to confront its evolution: how have ecosystem revenues – from albums sales to concerts, radio plays, digital downloads and streams – changed and been redistributed? What is the underlying value of music? Did streaming erode this value or correct it? What’s the logic behind streaming royalty models and where are its flaws and decencies? How can it be improved? After 15 years of declining consumer spend, it’s time to stop focusing on what was or “should” be. Industries don’t rebuild themselves.

PART I: HOW WE GOT HERE:

The Decline of Recorded Music Sales

Since the RIAA began its comprehensive database of US music sales in 1973, the category has never commanded less in consumer spend than it does today. On an inflation-adjusted basis, sales have plummeted by over 70% (or $14B) since 1999 – even though the American population has grown by some 46M over the period. And this decline is likely to continue. Digital revenues have begun to fall and CDs, which still represent 30% of sales, are unlikely to rebound. In Q3 of 2014, Wal-Mart, which moves one in every four physical discs sold in the United States, nearly halved the shelf space dedicated to the format, as well as the number of unique records it carried. In a few years, Amazon may be the only mass market retailer of physical music, at which point prices will undoubtedly tumble further.

What makes this decline particularly controversial is the fact that consumption of recorded music is greater than ever before. We listen to it wherever we go: on the subway, waiting in line, getting groceries and anywhere else we can. The soundtracks of our lives, so to speak, rarely stop. As a result, music executives often blame the collapse of revenues on iTunes’ 99¢ price points (and claim that the associated deal they struck with Apple arose only out of the extraordinary paranoia and confusion surrounding digital distribution and piracy in the early 2000s). However, much of the industry’s pre-iTunes value was inflated, held up only by bundle-based packaging (viz. albums), rather than consumer demand. Per track prices mattered, of course, but they’re also a distraction.

The End of the Age of Ownership: First Albums, then Tracks

The introduction of true a la carte music purchasing was bound to disrupt the music business. Everyone knew the album model had forced consumers to “own” tracks they didn’t want and prevented them from owning some of those they did, but how this would net out was impossible to predict. Nearly 15 years later, however, the answer has become clear.

By 2010, the total number of tracks (including album track equivalents) sold in the United States each year had fallen by 57% (to roughly 4.6B). Though it’s convenient to blame piracy, NPD estimates that fewer than 340M tracks were pirated in the United States in 2010 (~17M pirates downloading an average of 20 tracks each). Even if every one of these illegal downloads represented a cannibalized sale, the industry would still be down more than 50%. The same is true if the number of pirated tracks were somehow twice as many as NPD had estimated. With fewer than 1.5M Americans subscribed to music streaming services in 2010, this explanation also falls short. The end of the album didn’t just bring about the end of unearned revenues, it revealed that the underlying demand for “owned” music was much lower than most believed. Recognizing this fact is critical. If the music industry hopes to increase sales and better support its artists, revenues will need to be generated outside of conventional unit sales.

But first, it’s also important to note that the album-to-track conversion has been doubly bad for the most popular artists. In the album days, consumer spend was monopolized by a handful of $20 “must have” records released by the Beatles and Michael Jacksons of the world. Today, that same spend (or what’s left of it) can be spread across dozens of artists – with each one compensated only for the specific tracks a consumer picks.

by Jason Hirschhorn and Liam Boluk, REDEF | Read more:

Image: RIAA

There's An App For That

I have a mental map of everywhere in New York City I can freely do my business outside of my apartment in relative secrecy. There are the bathrooms halfway down the stairs to the Bethesda Fountain in Central Park, where the stall doors are too squat but everything smells decent. There’s the 4th floor of Century 21, where nobody will find you amid the hoards of tourists ripping through discount prom dresses. There’s the door behind the children’s book section of the Union Square Barnes & Noble, and the basement of the Old Navy in SoHo, and Grand Central Terminal and Penn Station and the Port Authority. Of course there are plenty of diners and Starbucks’ where I could order a coffee in exchange, but this is not . I have a volatile stomach and I should not have to pay to relieve it.

New York is not very welcome to my problems, but there are some solutions. There is now an app, Looie, where for $25 a month New Yorkers can reserve clean restrooms inside local businesses. It is only the latest in the many ways the sharing economy is trying to hack our bladders. Airpnp, Toilet Finder, and Nyrestroom.com all show us where in New York (and often the world) we can pee for something resembling free, whether it’s in exchange for the purchse of a coffee or just a dirty look and/or risk of expulsion from a hotel concierge. On a site like Nyrestroom, search for just “public restrooms” and the crowded map becomes painfully bare for such a dense city, especially considered most are in playgrounds, where adults are not allowed to enter without children. Why so few? And why should we be paying $25 for the privilege?

New York is not very welcome to my problems, but there are some solutions. There is now an app, Looie, where for $25 a month New Yorkers can reserve clean restrooms inside local businesses. It is only the latest in the many ways the sharing economy is trying to hack our bladders. Airpnp, Toilet Finder, and Nyrestroom.com all show us where in New York (and often the world) we can pee for something resembling free, whether it’s in exchange for the purchse of a coffee or just a dirty look and/or risk of expulsion from a hotel concierge. On a site like Nyrestroom, search for just “public restrooms” and the crowded map becomes painfully bare for such a dense city, especially considered most are in playgrounds, where adults are not allowed to enter without children. Why so few? And why should we be paying $25 for the privilege?

There used to be more. In subways you can still see them: scratched black doors with male and female caricatures. But like many restrooms in New York’s parks and other public spaces, they seem forever padlocked. Untapped Cities reported that out of the 129 bathrooms in the city’s subway stations, just 48 are unlocked, and I’m going to assume many of those aren’t handicap accessible. You’re basically shit out of luck (sorry) with any bathroom in public.

However, this is not a planned disruption on behalf of the sharing economy. They are just capitalizing on a system that long ago stopped considering public restrooms and public service, as well as a system that would rather not serve some members of the public.

New York is not very welcome to my problems, but there are some solutions. There is now an app, Looie, where for $25 a month New Yorkers can reserve clean restrooms inside local businesses. It is only the latest in the many ways the sharing economy is trying to hack our bladders. Airpnp, Toilet Finder, and Nyrestroom.com all show us where in New York (and often the world) we can pee for something resembling free, whether it’s in exchange for the purchse of a coffee or just a dirty look and/or risk of expulsion from a hotel concierge. On a site like Nyrestroom, search for just “public restrooms” and the crowded map becomes painfully bare for such a dense city, especially considered most are in playgrounds, where adults are not allowed to enter without children. Why so few? And why should we be paying $25 for the privilege?

New York is not very welcome to my problems, but there are some solutions. There is now an app, Looie, where for $25 a month New Yorkers can reserve clean restrooms inside local businesses. It is only the latest in the many ways the sharing economy is trying to hack our bladders. Airpnp, Toilet Finder, and Nyrestroom.com all show us where in New York (and often the world) we can pee for something resembling free, whether it’s in exchange for the purchse of a coffee or just a dirty look and/or risk of expulsion from a hotel concierge. On a site like Nyrestroom, search for just “public restrooms” and the crowded map becomes painfully bare for such a dense city, especially considered most are in playgrounds, where adults are not allowed to enter without children. Why so few? And why should we be paying $25 for the privilege?There used to be more. In subways you can still see them: scratched black doors with male and female caricatures. But like many restrooms in New York’s parks and other public spaces, they seem forever padlocked. Untapped Cities reported that out of the 129 bathrooms in the city’s subway stations, just 48 are unlocked, and I’m going to assume many of those aren’t handicap accessible. You’re basically shit out of luck (sorry) with any bathroom in public.

However, this is not a planned disruption on behalf of the sharing economy. They are just capitalizing on a system that long ago stopped considering public restrooms and public service, as well as a system that would rather not serve some members of the public.

by Jaya Saxena, The Hairpin | Read more:

Image: Amazon

Monday, July 27, 2015

No, It's Not Your Opinion. You're Just Wrong

[ed. Opinions are like farts. Everybody has 'em. It feels great to let 'em out. But mostly they just stink up the air.]

I spend far more time arguing on the Internet than can possibly be healthy, and the word I’ve come to loath more than any other is “opinion”. Opinion, or worse “belief”, has become the shield of every poorly-conceived notion that worms its way onto social media.

I spend far more time arguing on the Internet than can possibly be healthy, and the word I’ve come to loath more than any other is “opinion”. Opinion, or worse “belief”, has become the shield of every poorly-conceived notion that worms its way onto social media.

There’s a common conception that an opinion cannot be wrong. My dad said it. Hell, everyone’s dad probably said it and in the strictest terms it is true. However, before you crouch behind your Shield of Opinion you need to ask yourself two questions.

1. Is this actually an opinion?

2. If it is an opinion how informed is it and why do I hold it?

I’ll help you with the first part. An opinion is a preference for or judgment of something. My favorite color is black. I think mint tastes awful. Doctor Who is the best television show. These are all opinions. They may be unique to me alone or massively shared across the general population but they all have one thing in common; they cannot be verified outside the fact that I believe them.

There’s nothing wrong with an opinion on those things. The problem comes from people whose opinions are actually misconceptions. If you think vaccines cause autism you are expressing something factually wrong, not an opinion. The fact that you may still believe that vaccines cause autism does not move your misconception into the realm of valid opinion. Nor does the fact that many other share this opinion give it any more validity.

To quote John Oliver, who referenced a Gallup poll showing one in four Americans believe climate change isn’t real on his show, Last Week Tonight…

I have had so many conversations or email exchanges with students in the last few years wherein I anger them by indicating that simply saying, "This is my opinion" does not preclude a connected statement from being dead wrong. It still baffles me that some feel those four words somehow give them carte blanche to spout batshit oratory or prose. And it really scares me that some of those students think education that challenges their ideas is equivalent to an attack on their beliefs.

-Mick Cullen

I spend far more time arguing on the Internet than can possibly be healthy, and the word I’ve come to loath more than any other is “opinion”. Opinion, or worse “belief”, has become the shield of every poorly-conceived notion that worms its way onto social media.

I spend far more time arguing on the Internet than can possibly be healthy, and the word I’ve come to loath more than any other is “opinion”. Opinion, or worse “belief”, has become the shield of every poorly-conceived notion that worms its way onto social media.There’s a common conception that an opinion cannot be wrong. My dad said it. Hell, everyone’s dad probably said it and in the strictest terms it is true. However, before you crouch behind your Shield of Opinion you need to ask yourself two questions.

1. Is this actually an opinion?

2. If it is an opinion how informed is it and why do I hold it?

I’ll help you with the first part. An opinion is a preference for or judgment of something. My favorite color is black. I think mint tastes awful. Doctor Who is the best television show. These are all opinions. They may be unique to me alone or massively shared across the general population but they all have one thing in common; they cannot be verified outside the fact that I believe them.

There’s nothing wrong with an opinion on those things. The problem comes from people whose opinions are actually misconceptions. If you think vaccines cause autism you are expressing something factually wrong, not an opinion. The fact that you may still believe that vaccines cause autism does not move your misconception into the realm of valid opinion. Nor does the fact that many other share this opinion give it any more validity.

To quote John Oliver, who referenced a Gallup poll showing one in four Americans believe climate change isn’t real on his show, Last Week Tonight…

Who gives a shit? You don’t need people’s opinion on a fact. You might as well have a poll asking: “Which number is bigger, 15 or 5?” or “Do owls exist?” or “Are there hats?”by Jef Rouner, Houston Chronicle | Read more:

Image: via:

Blacked Out: The Fine Print

Getting booked to play a summer festival like Timber!, Sasquatch, or the Capitol Hill Block Party brings a band a certain prestige. Once lineups are announced, participants are often quick to promote the fact. But the increasing number of summer festivals also means something many music fans may not know about: blackout dates.

For most, the term “blackout date” refers to credit cards and airline miles. But in the music community, it means a specific duration before and after a show date during which bands contractually can’t play within a certain radius of a gig. It’s a type of non-compete clause.

This agreement has many ripple affects. It’s meant to discourage festival bill crossover and oversaturation of a band in a given market, as well as increase excitement for exclusive festival gigs. But it also limits a band’s moneymaking opportunities locally, and can tie the hands of club owners trying to bring in summer audiences.

This agreement has many ripple affects. It’s meant to discourage festival bill crossover and oversaturation of a band in a given market, as well as increase excitement for exclusive festival gigs. But it also limits a band’s moneymaking opportunities locally, and can tie the hands of club owners trying to bring in summer audiences.

“It’s rough on the whole music community,” says Jodi Ecklund, talent buyer at Chop Suey. “Festivals attract a bunch of bridge-and-tunnel folks. They sell out prior to even announcing their lineup. It doesn’t really matter who’s on the bill. I have bands that cannot play again until October due to Sasquatch, Block Party, and Bumbershoot.”

Don Strasburg, co-president and senior talent buyer for AEG Live Rocky Mountains and AEG Live Northwest, the outfit that took over production of Bumbershoot this year, says he and his group look for a “certain level of exclusivity.”As Strasburg puts it, “overplaying is generally not going to help create desire. I’m not saying local artists should play once a year—but two months is not that long a time.”

Jason Lajeunesse, talent buyer for CHBP and booker for Neumos and Barboza, says his festival is “pretty flexible” with local bands. While the blackout dates vary for local versus national bands, he says, there is at least a 100-mile-radius restriction with a 30–90 day blackout in advance of a show. “And, generally speaking,” he says, “as soon as the performance is over, it’s OK for bands to advertise their upcoming show.” But here’s his hard line: “If we’re guaranteeing an artist up-front money to play, you can’t be playing the market multiple times.”

But therein lies the issue: Local bands aren’t making gobs of money from festivals—certainly not enough to make blacking out all these dates and venues financially worthwhile. Sometimes bands make as little as $200 per festival gig. Split four ways, that’s hardly worth the time.

“If you’re an artist,” says Lajeunesse, “and want to build your career, you don’t want to be overplaying and saturating your market, as a rule. I don’t believe a band should be playing every three weeks if they want to make those shows special.”

Many might agree with this sentiment. According to Daniel Chesney of local power-pop surf group Snuff Redux, the band’s CHBP contractual blackout dates for this year totaled “90 days, 45 before and 45 after (with a 120 mile radius). But we negotiated them down from another larger blackout,” he says, “so what we have is pared down. We bargained down all the blackout arrangements so that we could have time playing Seattle after our tour. But to be honest, the blackout has been relatively useful for us as a group. We went from playing shows nonstop all the time to having an excuse to sit down and work on new material and releases. Not that people don’t ignore their blackouts all the time... but it seemed prudent to use the time they expected us to be quiet well.”

But the problem is: Shouldn’t bands themselves be making that decision, not contractual black-out dates? Evan Flory-Barnes of local instrumental jazz group Industrial Revelation explains that the proximity restrictions associated with CHBP prevented his band from playing Sasquatch and opening for well-known jazz pianist Robert Glasper.

“I think blackout dates are from the same era as ‘pay to play’ and the era of playing for ‘exposure,’” Flory-Barnes says. “No one limits the opportunity for club owners and talent buyers to do their thing, but when it comes to a musician being entrepreneurial, it’s a different story. Blackout dates represent an old model established when there was fewer people in the city and fewer people listening to music.”

by Jake Uitti, Seattle Weekly | Read more:

Image: Kelton Sears

For most, the term “blackout date” refers to credit cards and airline miles. But in the music community, it means a specific duration before and after a show date during which bands contractually can’t play within a certain radius of a gig. It’s a type of non-compete clause.

This agreement has many ripple affects. It’s meant to discourage festival bill crossover and oversaturation of a band in a given market, as well as increase excitement for exclusive festival gigs. But it also limits a band’s moneymaking opportunities locally, and can tie the hands of club owners trying to bring in summer audiences.

This agreement has many ripple affects. It’s meant to discourage festival bill crossover and oversaturation of a band in a given market, as well as increase excitement for exclusive festival gigs. But it also limits a band’s moneymaking opportunities locally, and can tie the hands of club owners trying to bring in summer audiences.“It’s rough on the whole music community,” says Jodi Ecklund, talent buyer at Chop Suey. “Festivals attract a bunch of bridge-and-tunnel folks. They sell out prior to even announcing their lineup. It doesn’t really matter who’s on the bill. I have bands that cannot play again until October due to Sasquatch, Block Party, and Bumbershoot.”

Don Strasburg, co-president and senior talent buyer for AEG Live Rocky Mountains and AEG Live Northwest, the outfit that took over production of Bumbershoot this year, says he and his group look for a “certain level of exclusivity.”As Strasburg puts it, “overplaying is generally not going to help create desire. I’m not saying local artists should play once a year—but two months is not that long a time.”

Jason Lajeunesse, talent buyer for CHBP and booker for Neumos and Barboza, says his festival is “pretty flexible” with local bands. While the blackout dates vary for local versus national bands, he says, there is at least a 100-mile-radius restriction with a 30–90 day blackout in advance of a show. “And, generally speaking,” he says, “as soon as the performance is over, it’s OK for bands to advertise their upcoming show.” But here’s his hard line: “If we’re guaranteeing an artist up-front money to play, you can’t be playing the market multiple times.”

But therein lies the issue: Local bands aren’t making gobs of money from festivals—certainly not enough to make blacking out all these dates and venues financially worthwhile. Sometimes bands make as little as $200 per festival gig. Split four ways, that’s hardly worth the time.

“If you’re an artist,” says Lajeunesse, “and want to build your career, you don’t want to be overplaying and saturating your market, as a rule. I don’t believe a band should be playing every three weeks if they want to make those shows special.”

Many might agree with this sentiment. According to Daniel Chesney of local power-pop surf group Snuff Redux, the band’s CHBP contractual blackout dates for this year totaled “90 days, 45 before and 45 after (with a 120 mile radius). But we negotiated them down from another larger blackout,” he says, “so what we have is pared down. We bargained down all the blackout arrangements so that we could have time playing Seattle after our tour. But to be honest, the blackout has been relatively useful for us as a group. We went from playing shows nonstop all the time to having an excuse to sit down and work on new material and releases. Not that people don’t ignore their blackouts all the time... but it seemed prudent to use the time they expected us to be quiet well.”

But the problem is: Shouldn’t bands themselves be making that decision, not contractual black-out dates? Evan Flory-Barnes of local instrumental jazz group Industrial Revelation explains that the proximity restrictions associated with CHBP prevented his band from playing Sasquatch and opening for well-known jazz pianist Robert Glasper.

“I think blackout dates are from the same era as ‘pay to play’ and the era of playing for ‘exposure,’” Flory-Barnes says. “No one limits the opportunity for club owners and talent buyers to do their thing, but when it comes to a musician being entrepreneurial, it’s a different story. Blackout dates represent an old model established when there was fewer people in the city and fewer people listening to music.”

by Jake Uitti, Seattle Weekly | Read more:

Image: Kelton Sears

Forget Ashley Madison, the Big One's Coming

Computer experts have long warned about a catastrophic cyber-attack in the US, a sort of Web 3.0 version of 9/11 that would wreak enormous damage throughout the country. Like most Americans, I shrugged. With all of the enormous resources the country enjoys, those warnings seemed like the rantings of a digital Chicken Little.

Oddly enough, the revelations of the National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden gave me some false comfort. If the powerful NSA was so good at hacking its own citizens, then surely the agency could prevent criminals, terrorists and foreign enemies from doing the same?

Oddly enough, the revelations of the National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden gave me some false comfort. If the powerful NSA was so good at hacking its own citizens, then surely the agency could prevent criminals, terrorists and foreign enemies from doing the same?

And then there’s Silicon Valley, which I frequently write about. Surely the uber-geeks who run the world’s greatest innovation cluster could code something to smite the evildoers? Well, on behalf on the US, I admit I was terribly wrong. We are so screwed.

I came to this conclusion recently, over a span of seven days. Earlier this month I attended a preview of retail giant Target’s new “Internet of Things” showroom in downtown San Francisco. The company had constructed a mock house intended to show how “smart devices” connected to the internet could seamlessly work together to automate the 21st-century digital home. A car alarm wakes up the baby sleeping in the nursery. A sensor detects the baby’s cries, alerts the parents and automatically triggers the stereo to play soothing music.

It was all very impressive, but I couldn’t help notice an irony: the retailer that in 2013 was subject to a hack that comprised the credit-card data of 100 million consumers now wanted people to entrust their entire homes to the internet. “It’s been a long time coming, but we are just getting started,” a Target executive said.

One week later I found myself at a dinner in a fancy hotel to discuss cybersecurity with the executives of top Silicon Valley firms. Unlike the festive Target event, the mood was decidedly grim. Actually it was downright alarming.

Forget about the Sony and Ashley Madison hacks. Those cyberthefts may cost companies some money and embarrassment, but that’s not what the execs were nervous about. Even the successful breach of Chrysler’s in-car systems, which allowed hackers to take control of a Jeep on the highway and prompted the recall of 1.4 million vehicles, is a mere appetiser compared with what’s coming down the road.

By 2020 the US will be hit with an earthquake of a cyber-attack that will cripple banks, stock exchanges, power plants and communications, an executive from Hewlett-Packard predicted. Companies are nowhere near prepared for it. Neither are the Feds. And yet, instead of mobilising a national defence, we want a toaster that communicates with the washing machine over the internet.

Oddly enough, the revelations of the National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden gave me some false comfort. If the powerful NSA was so good at hacking its own citizens, then surely the agency could prevent criminals, terrorists and foreign enemies from doing the same?

Oddly enough, the revelations of the National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden gave me some false comfort. If the powerful NSA was so good at hacking its own citizens, then surely the agency could prevent criminals, terrorists and foreign enemies from doing the same?And then there’s Silicon Valley, which I frequently write about. Surely the uber-geeks who run the world’s greatest innovation cluster could code something to smite the evildoers? Well, on behalf on the US, I admit I was terribly wrong. We are so screwed.

I came to this conclusion recently, over a span of seven days. Earlier this month I attended a preview of retail giant Target’s new “Internet of Things” showroom in downtown San Francisco. The company had constructed a mock house intended to show how “smart devices” connected to the internet could seamlessly work together to automate the 21st-century digital home. A car alarm wakes up the baby sleeping in the nursery. A sensor detects the baby’s cries, alerts the parents and automatically triggers the stereo to play soothing music.

It was all very impressive, but I couldn’t help notice an irony: the retailer that in 2013 was subject to a hack that comprised the credit-card data of 100 million consumers now wanted people to entrust their entire homes to the internet. “It’s been a long time coming, but we are just getting started,” a Target executive said.

One week later I found myself at a dinner in a fancy hotel to discuss cybersecurity with the executives of top Silicon Valley firms. Unlike the festive Target event, the mood was decidedly grim. Actually it was downright alarming.