The British author Douglas Adams had this to say about airports: “Airports are ugly. Some are very ugly. Some attain a degree of ugliness that can only be the result of special effort.” Sadly, this truth is not applicable merely to airports: it can also be said of most contemporary architecture.

Take the Tour Montparnasse, a black, slickly glass-panelled skyscraper, looming over the beautiful Paris cityscape like a giant domino waiting to fall. Parisians hated it so much that the city was subsequently forced to enact an ordinance forbidding any further skyscrapers higher than 36 meters.

Or take Boston’s City Hall Plaza. Downtown Boston is generally an attractive place, with old buildings and a waterfront and a beautiful public garden. But Boston’s City Hall is a hideous concrete edifice of mind-bogglingly inscrutable shape, like an ominous component found left over after you’ve painstakingly assembled a complicated household appliance. In the 1960s, before the first batch of concrete had even dried in the mold, people were already begging preemptively for the damn thing to be torn down. There’s a whole additional complex of equally unpleasant federal buildings attached to the same plaza, designed by Walter Gropius, an architect whose chuckle-inducing surname belies the utter cheerlessness of his designs. The John F. Kennedy Building, for example—featurelessly grim on the outside, infuriatingly unnavigable on the inside—is where, among other things, terrified immigrants attend their deportation hearings, and where traumatized veterans come to apply for benefits. Such an inhospitable building sends a very clear message, which is: the government wants its lowly supplicants to feel confused, alienated, and afraid.

The fact is, contemporary architecture gives most regular humans the heebie-jeebies. Try telling that to architects and their acolytes, though, and you’ll get an earful about why your feeling is misguided, the product of some embarrassing misconception about architectural principles. One defense, typically, is that these eyesores are, in reality, incredible feats of engineering. After all, “blobitecture”—which, we regret to say, is a real school of contemporary architecture—is created using complicated computer-driven algorithms! You may think the ensuing blob-structure looks like a tentacled turd, or a crumpled kleenex, but that’s because you don’t have an architect’s trained eye.

The fact is, contemporary architecture gives most regular humans the heebie-jeebies. Try telling that to architects and their acolytes, though, and you’ll get an earful about why your feeling is misguided, the product of some embarrassing misconception about architectural principles. One defense, typically, is that these eyesores are, in reality, incredible feats of engineering. After all, “blobitecture”—which, we regret to say, is a real school of contemporary architecture—is created using complicated computer-driven algorithms! You may think the ensuing blob-structure looks like a tentacled turd, or a crumpled kleenex, but that’s because you don’t have an architect’s trained eye.

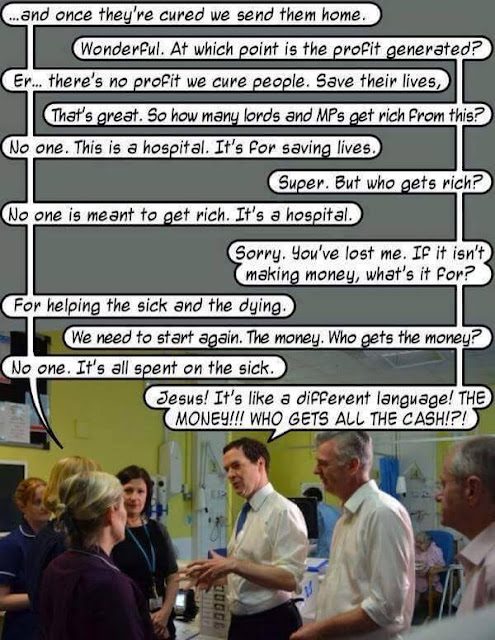

Another thing you will often hear from design-school types is that contemporary architecture is honest. It doesn’t rely on the forms and usages of the past, and it is not interested in coddling you and your dumb feelings. Wake up, sheeple! Your boss hates you, and your bloodsucking landlord too, and your government fully intends to grind you between its gears. That’s the world we live in! Get used to it! Fans of Brutalism—the blocky-industrial-concrete school of architecture—are quick to emphasize that these buildings tell it like it is, as if this somehow excused the fact that they look, at best, dreary, and, at worst, like the headquarters of some kind of post-apocalyptic totalitarian dictatorship.

Let’s be really honest with ourselves: a brief glance at any structure designed in the last 50 years should be enough to persuade anyone that something has gone deeply, terribly wrong with us. Some unseen person or force seems committed to replacing literally every attractive and appealing thing with an ugly and unpleasant thing. The architecture produced by contemporary global capitalism is possibly the most obvious visible evidence that it has some kind of perverse effect on the human soul. Of course, there is no accounting for taste, and there may be some among us who are naturally are deeply disposed to appreciate blobs and blocks. But polling suggests that devotees of contemporary architecture are overwhelmingly in the minority: aside from monuments, few of the public’s favorite structures are from the postwar period. (When the results of the poll were released, architects harrumphed that it didn’t “reflect expert judgment” but merely people’s “emotions,” a distinction that rather proves the entire point.) And when it comes to architecture, as distinct from most other forms of art, it isn’t enough to simply shrug and say that personal preferences differ: where public buildings are concerned, or public spaces which have an existing character and historic resonances for the people who live there, to impose an architect’s eccentric will on the masses, and force them to spend their days in spaces they find ugly and unsettling, is actually oppressive and cruel.

The politics of this issue, moreover, are all upside-down. For example, how do we explain why, in the aftermath of the Grenfell Tower tragedy in London, more conservative commentators were calling for more comfortable and home-like public housing, while left-wing writers staunchly defended the populist spirit of the high-rise apartment building, despite ample evidence that the majority of people would prefer not to be forced to live in or among such places? Conservatives who critique public housing may have easily-proven ulterior motives, but why so many on the left are wedded to defending unpopular schools of architectural and urban design is less immediately obvious.

There have, after all, been moments in the history of socialism—like the Arts & Crafts movement in late 19th-century England—where the creation of beautiful things was seen as part and parcel of building a fairer, kinder world. A shared egalitarian social undertaking, ideally, ought to be one of joy as well as struggle: in these desperate times, there are certainly more overwhelming imperatives than making the world beautiful to look at, but to decline to make the world more beautiful when it’s in your power to so, or to destroy some beautiful thing without need, is a grotesque perversion of the cooperative ideal. This is especially true when it comes to architecture. The environments we surround ourselves with have the power to shape our thoughts and emotions. People trammeled in on all sides by ugliness are often unhappy without even knowing why. If you live in a place where you are cut off from light, and nature, and color, and regular communion with other humans, it is easy to become desperate, lonely, and depressed. The question is: how did contemporary architecture wind up like this? And how can it be fixed?

For about 2,000 years, everything human beings built was beautiful, or at least unobjectionable. The 20th century put a stop to this, evidenced by the fact that people often go out of their way to vacation in “historic” (read: beautiful) towns that contain as little postwar architecture as possible. But why? What actually changed? Why does there seem to be such an obvious break between the thousands of years before World War II and the postwar period? And why does this seem to hold true everywhere? (...)

Architecture’s abandonment of the principle of “aesthetic coherence” is creating serious damage to ancient cityscapes. The belief that “buildings should look like their times” rather than “buildings should look like the buildings in the place where they are being built” leads toward a hodge-podge, with all the benefits that come from a distinct and orderly local style being destroyed by a few buildings that undermine the coherence of the whole. This is partly a function of the free market approach to design and development, which sacrifices the possibility of ever again producing a place on the village or city level that has an impressive stylistic coherence. A revulsion (from both progressives and capitalist individualists alike) at the idea of “forced uniformity” leads to an abandonment of any community aesthetic traditions, with every building fitting equally well in Panama City, Dubai, New York City, or Shanghai. Because decisions over what to build are left to the individual property owner, and rich people often have horrible taste and simply prefer things that are huge and imposing, all possibilities for creating another city with the distinctiveness of a Venice or Bruges are erased forever.(...)

How, then, do we fix architecture? What makes for a better-looking world? If everything is ugly, how do we fix it? Cutting through all of the colossally mistaken theoretical justifications for contemporary design is a major project. But a few principles may prove helpful.

Take the Tour Montparnasse, a black, slickly glass-panelled skyscraper, looming over the beautiful Paris cityscape like a giant domino waiting to fall. Parisians hated it so much that the city was subsequently forced to enact an ordinance forbidding any further skyscrapers higher than 36 meters.

Or take Boston’s City Hall Plaza. Downtown Boston is generally an attractive place, with old buildings and a waterfront and a beautiful public garden. But Boston’s City Hall is a hideous concrete edifice of mind-bogglingly inscrutable shape, like an ominous component found left over after you’ve painstakingly assembled a complicated household appliance. In the 1960s, before the first batch of concrete had even dried in the mold, people were already begging preemptively for the damn thing to be torn down. There’s a whole additional complex of equally unpleasant federal buildings attached to the same plaza, designed by Walter Gropius, an architect whose chuckle-inducing surname belies the utter cheerlessness of his designs. The John F. Kennedy Building, for example—featurelessly grim on the outside, infuriatingly unnavigable on the inside—is where, among other things, terrified immigrants attend their deportation hearings, and where traumatized veterans come to apply for benefits. Such an inhospitable building sends a very clear message, which is: the government wants its lowly supplicants to feel confused, alienated, and afraid.

The fact is, contemporary architecture gives most regular humans the heebie-jeebies. Try telling that to architects and their acolytes, though, and you’ll get an earful about why your feeling is misguided, the product of some embarrassing misconception about architectural principles. One defense, typically, is that these eyesores are, in reality, incredible feats of engineering. After all, “blobitecture”—which, we regret to say, is a real school of contemporary architecture—is created using complicated computer-driven algorithms! You may think the ensuing blob-structure looks like a tentacled turd, or a crumpled kleenex, but that’s because you don’t have an architect’s trained eye.

The fact is, contemporary architecture gives most regular humans the heebie-jeebies. Try telling that to architects and their acolytes, though, and you’ll get an earful about why your feeling is misguided, the product of some embarrassing misconception about architectural principles. One defense, typically, is that these eyesores are, in reality, incredible feats of engineering. After all, “blobitecture”—which, we regret to say, is a real school of contemporary architecture—is created using complicated computer-driven algorithms! You may think the ensuing blob-structure looks like a tentacled turd, or a crumpled kleenex, but that’s because you don’t have an architect’s trained eye. Another thing you will often hear from design-school types is that contemporary architecture is honest. It doesn’t rely on the forms and usages of the past, and it is not interested in coddling you and your dumb feelings. Wake up, sheeple! Your boss hates you, and your bloodsucking landlord too, and your government fully intends to grind you between its gears. That’s the world we live in! Get used to it! Fans of Brutalism—the blocky-industrial-concrete school of architecture—are quick to emphasize that these buildings tell it like it is, as if this somehow excused the fact that they look, at best, dreary, and, at worst, like the headquarters of some kind of post-apocalyptic totalitarian dictatorship.

Let’s be really honest with ourselves: a brief glance at any structure designed in the last 50 years should be enough to persuade anyone that something has gone deeply, terribly wrong with us. Some unseen person or force seems committed to replacing literally every attractive and appealing thing with an ugly and unpleasant thing. The architecture produced by contemporary global capitalism is possibly the most obvious visible evidence that it has some kind of perverse effect on the human soul. Of course, there is no accounting for taste, and there may be some among us who are naturally are deeply disposed to appreciate blobs and blocks. But polling suggests that devotees of contemporary architecture are overwhelmingly in the minority: aside from monuments, few of the public’s favorite structures are from the postwar period. (When the results of the poll were released, architects harrumphed that it didn’t “reflect expert judgment” but merely people’s “emotions,” a distinction that rather proves the entire point.) And when it comes to architecture, as distinct from most other forms of art, it isn’t enough to simply shrug and say that personal preferences differ: where public buildings are concerned, or public spaces which have an existing character and historic resonances for the people who live there, to impose an architect’s eccentric will on the masses, and force them to spend their days in spaces they find ugly and unsettling, is actually oppressive and cruel.

The politics of this issue, moreover, are all upside-down. For example, how do we explain why, in the aftermath of the Grenfell Tower tragedy in London, more conservative commentators were calling for more comfortable and home-like public housing, while left-wing writers staunchly defended the populist spirit of the high-rise apartment building, despite ample evidence that the majority of people would prefer not to be forced to live in or among such places? Conservatives who critique public housing may have easily-proven ulterior motives, but why so many on the left are wedded to defending unpopular schools of architectural and urban design is less immediately obvious.

There have, after all, been moments in the history of socialism—like the Arts & Crafts movement in late 19th-century England—where the creation of beautiful things was seen as part and parcel of building a fairer, kinder world. A shared egalitarian social undertaking, ideally, ought to be one of joy as well as struggle: in these desperate times, there are certainly more overwhelming imperatives than making the world beautiful to look at, but to decline to make the world more beautiful when it’s in your power to so, or to destroy some beautiful thing without need, is a grotesque perversion of the cooperative ideal. This is especially true when it comes to architecture. The environments we surround ourselves with have the power to shape our thoughts and emotions. People trammeled in on all sides by ugliness are often unhappy without even knowing why. If you live in a place where you are cut off from light, and nature, and color, and regular communion with other humans, it is easy to become desperate, lonely, and depressed. The question is: how did contemporary architecture wind up like this? And how can it be fixed?

For about 2,000 years, everything human beings built was beautiful, or at least unobjectionable. The 20th century put a stop to this, evidenced by the fact that people often go out of their way to vacation in “historic” (read: beautiful) towns that contain as little postwar architecture as possible. But why? What actually changed? Why does there seem to be such an obvious break between the thousands of years before World War II and the postwar period? And why does this seem to hold true everywhere? (...)

Architecture’s abandonment of the principle of “aesthetic coherence” is creating serious damage to ancient cityscapes. The belief that “buildings should look like their times” rather than “buildings should look like the buildings in the place where they are being built” leads toward a hodge-podge, with all the benefits that come from a distinct and orderly local style being destroyed by a few buildings that undermine the coherence of the whole. This is partly a function of the free market approach to design and development, which sacrifices the possibility of ever again producing a place on the village or city level that has an impressive stylistic coherence. A revulsion (from both progressives and capitalist individualists alike) at the idea of “forced uniformity” leads to an abandonment of any community aesthetic traditions, with every building fitting equally well in Panama City, Dubai, New York City, or Shanghai. Because decisions over what to build are left to the individual property owner, and rich people often have horrible taste and simply prefer things that are huge and imposing, all possibilities for creating another city with the distinctiveness of a Venice or Bruges are erased forever.(...)

How, then, do we fix architecture? What makes for a better-looking world? If everything is ugly, how do we fix it? Cutting through all of the colossally mistaken theoretical justifications for contemporary design is a major project. But a few principles may prove helpful.

by Brianna Rennix & Nathan J. Robinson, Current Affairs : Read more: