Kumi Yamashita

via:

Thursday, March 31, 2011

Adventures in Marketing

Name a snack food that's neon orange and makes a loud crunch when munched.

If you picked Cheetos, the nation's biggest producer of baby carrots wants you to think again.

Just in time for the battle over what's gonna be in millions of back-to-school lunches, Bolthouse Farms and nearly 50 other carrot growers today will unveil plans for the industry's first-ever marketing campaign. The $25 million effort sets its sights on a giant, big-spending rival: junk food.

Heat and Light

by James Kingsland

It's 200 years to the day since the birth of Robert Bunsen, the German chemist famous for inventing the ubiquitous Bunsen burner. But Bunsen's scientific legacy is far, far more important than that – he was one of the most ingenious chemists of the 19th century, whose work led to the discovery of a new element, an antidote for arsenic poisoning and would one day provide clues to the constituents of stars.

For this modest, quiet man, the Bunsen burner was simply a means to an end. Bunsen and his faithful lab assistant Peter Desaga (surely the original Beaker?) needed a very hot, clean flame to pursue their main interest: the characteristic, brightly coloured light emitted by different elements when they are heated. Bunsen was the first person to study these "emission spectra" systematically.

For this modest, quiet man, the Bunsen burner was simply a means to an end. Bunsen and his faithful lab assistant Peter Desaga (surely the original Beaker?) needed a very hot, clean flame to pursue their main interest: the characteristic, brightly coloured light emitted by different elements when they are heated. Bunsen was the first person to study these "emission spectra" systematically.

Bunsen and his colleague Gustav Kirchhoff went on to split this light into its constituent wavelengths using a prism, in the process inventing a prototype of today's spectroscopes and founding the brand new scientific field of spectroscopy. They discovered that every element emits a distinctive mix of wavelengths that can be used like a fingerprint to identify its presence.

Bunsen identified the emission spectra of sodium, lithium and potassium. He also detected a previously unseen blue spectral line produced by mineral water which he guessed was being emitted by an unknown element. Having gone to the extraordinary length of distilling 40 tonnes of water to isolate 17 grams of the new element, he called it caesium, meaning "deep blue" in Latin. (As the radioactive isotope caesium-137 – with a half life of around 30 years – it's responsible for the deadly legacy of nuclear accidents like Chernobyl).

Read more:

It's 200 years to the day since the birth of Robert Bunsen, the German chemist famous for inventing the ubiquitous Bunsen burner. But Bunsen's scientific legacy is far, far more important than that – he was one of the most ingenious chemists of the 19th century, whose work led to the discovery of a new element, an antidote for arsenic poisoning and would one day provide clues to the constituents of stars.

For this modest, quiet man, the Bunsen burner was simply a means to an end. Bunsen and his faithful lab assistant Peter Desaga (surely the original Beaker?) needed a very hot, clean flame to pursue their main interest: the characteristic, brightly coloured light emitted by different elements when they are heated. Bunsen was the first person to study these "emission spectra" systematically.

For this modest, quiet man, the Bunsen burner was simply a means to an end. Bunsen and his faithful lab assistant Peter Desaga (surely the original Beaker?) needed a very hot, clean flame to pursue their main interest: the characteristic, brightly coloured light emitted by different elements when they are heated. Bunsen was the first person to study these "emission spectra" systematically.Bunsen and his colleague Gustav Kirchhoff went on to split this light into its constituent wavelengths using a prism, in the process inventing a prototype of today's spectroscopes and founding the brand new scientific field of spectroscopy. They discovered that every element emits a distinctive mix of wavelengths that can be used like a fingerprint to identify its presence.

Bunsen identified the emission spectra of sodium, lithium and potassium. He also detected a previously unseen blue spectral line produced by mineral water which he guessed was being emitted by an unknown element. Having gone to the extraordinary length of distilling 40 tonnes of water to isolate 17 grams of the new element, he called it caesium, meaning "deep blue" in Latin. (As the radioactive isotope caesium-137 – with a half life of around 30 years – it's responsible for the deadly legacy of nuclear accidents like Chernobyl).

Read more:

Cosmonaut Crashed Into Earth 'Crying In Rage'

by Robert Krulwich

So there's a cosmonaut up in space, circling the globe, convinced he will never make it back to Earth; he's on the phone with Alexei Kosygin — then a high official of the Soviet Union — who is crying because he, too, thinks the cosmonaut will die.

The space vehicle is shoddily constructed, running dangerously low on fuel; its parachutes — though no one knows this — won't work and the cosmonaut, Vladimir Komarov, is about to, literally, crash full speed into Earth, his body turning molten on impact. As he heads to his doom, U.S. listening posts in Turkey hear him crying in rage, "cursing the people who had put him inside a botched spaceship."

Starman tells the story of a friendship between two cosmonauts, Vladimir Kamarov and Soviet hero Yuri Gagarin, the first human to reach outer space. The two men were close; they socialized, hunted and drank together.

In 1967, both men were assigned to the same Earth-orbiting mission, and both knew the space capsule was not safe to fly. Komarov told friends he knew he would probably die. But he wouldn't back out because he didn't want Gagarin to die. Gagarin would have been his replacement.

Both sides in the 1960s race to space knew these missions were dangerous. We sometimes forget how dangerous. In January of that same year, 1967, Americans Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee died in a fire inside an Apollo capsule.

Two years later, when Americans landed on the moon, the Nixon White House had a just-in-case statement, prepared by speechwriter William Safire, announcing the death of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, had they been marooned or killed. Death was not unexpected.

Read more:

So there's a cosmonaut up in space, circling the globe, convinced he will never make it back to Earth; he's on the phone with Alexei Kosygin — then a high official of the Soviet Union — who is crying because he, too, thinks the cosmonaut will die.

The space vehicle is shoddily constructed, running dangerously low on fuel; its parachutes — though no one knows this — won't work and the cosmonaut, Vladimir Komarov, is about to, literally, crash full speed into Earth, his body turning molten on impact. As he heads to his doom, U.S. listening posts in Turkey hear him crying in rage, "cursing the people who had put him inside a botched spaceship."

Starman tells the story of a friendship between two cosmonauts, Vladimir Kamarov and Soviet hero Yuri Gagarin, the first human to reach outer space. The two men were close; they socialized, hunted and drank together.

In 1967, both men were assigned to the same Earth-orbiting mission, and both knew the space capsule was not safe to fly. Komarov told friends he knew he would probably die. But he wouldn't back out because he didn't want Gagarin to die. Gagarin would have been his replacement.

Both sides in the 1960s race to space knew these missions were dangerous. We sometimes forget how dangerous. In January of that same year, 1967, Americans Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee died in a fire inside an Apollo capsule.

Two years later, when Americans landed on the moon, the Nixon White House had a just-in-case statement, prepared by speechwriter William Safire, announcing the death of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, had they been marooned or killed. Death was not unexpected.

Read more:

Christmas Truce

During the First World War, drafts created the armies that were drawn from remarkably similar societies for the first time in modern warfare. Along the Western Front, on both sides there were industrial workers and farm laborers. On both sides there were aristocratic senior officers and middle-class junior officers. For Catholics, Protestants and Jews fighting for separate armies, they sometimes identified more with their religious brethren on the opposing side than with their fellow soldiers.

The soldiers, Englishmen, Frenchmen, Germans and Italians were equally irreverent about what they were supposedly fighting for. Over the longer period of trench warfare, a kind of ‘live and let live’ attitude developed in certain relatively quiet sectors of the line; war was reduced to a series of rituals, as with the Greeks and Trojans. English pacifist Vera Brittain noted about a Scottish and a Saxon regiment that had agreed not to aim at each other when they fired. They made a lot of noise and an outsider would have thought the men were fighting hard, but in practice no one was hit. Robert Graves — in his pivotal memoir of the Great War, Goodbye to All That — recollected about letters arriving from the Germans, rolled up in old mortar shells: “Your little dog has run over to us, and we are keeping it safe here.” Newspapers were fired back and forth in the same fashion. Louis Barthas spent some time in a sector where the Germans and the French fired only six mortar rounds a day, ‘out of courtesy’.

Nothing symbolized this easygoing attitudes more than the informal Christmas truce of 1914, when opposing soldiers in many sectors joined together to sing carols, and exchange Christmas greetings and gifts. Soccer games were played in no man’s land with makeshift balls. Of course, there were some who refused to participate in the truce; among those was a German field messenger named Adolf Hitler, who grumbled, ““Such things should not happen in wartime. Have you Germans no sense of honor left at all?”

At Diksmuide, Belgium, the Belgian and German soldiers famously celebrated Christmas Eve together in 1914, drinking schapps together. One year later, ad hoc ceasefires took place again, this time in northern France. No man’s land was suddenly transformed into ‘a country fair’ as lively bartering began for schnapps, cigarettes, coffee, uniform buttons and other trinkets. More worryingly for their superiors, the soldiers sang the Internationale.

Yet socialist hopes that soldiers would ultimately repudiate their national loyalties for the sake of international brotherhood were proven to be futile. Christmas Truce was almost the last hurrah of a bygone era; as the war went on, mutual hatred grew, expunging the common origins and predicament of the combatants. War, too, has lost its mystique; soon, only fools would celebrate it or enter it with excited patriotic fervor. After August 1914, when thousands of red-trousered Frenchmen and white-gloved officers in full dress and plumes were decimated by German machine guns, France eschewed her pride and switched to neutral-colored service uniforms — the last world power to do so. Soon, there will be no more sabres and Sam Browne belts, no more centuries-old habits of chivalry, no more leaving civilians out of war.

via:

hat tip:

The soldiers, Englishmen, Frenchmen, Germans and Italians were equally irreverent about what they were supposedly fighting for. Over the longer period of trench warfare, a kind of ‘live and let live’ attitude developed in certain relatively quiet sectors of the line; war was reduced to a series of rituals, as with the Greeks and Trojans. English pacifist Vera Brittain noted about a Scottish and a Saxon regiment that had agreed not to aim at each other when they fired. They made a lot of noise and an outsider would have thought the men were fighting hard, but in practice no one was hit. Robert Graves — in his pivotal memoir of the Great War, Goodbye to All That — recollected about letters arriving from the Germans, rolled up in old mortar shells: “Your little dog has run over to us, and we are keeping it safe here.” Newspapers were fired back and forth in the same fashion. Louis Barthas spent some time in a sector where the Germans and the French fired only six mortar rounds a day, ‘out of courtesy’.

Nothing symbolized this easygoing attitudes more than the informal Christmas truce of 1914, when opposing soldiers in many sectors joined together to sing carols, and exchange Christmas greetings and gifts. Soccer games were played in no man’s land with makeshift balls. Of course, there were some who refused to participate in the truce; among those was a German field messenger named Adolf Hitler, who grumbled, ““Such things should not happen in wartime. Have you Germans no sense of honor left at all?”

At Diksmuide, Belgium, the Belgian and German soldiers famously celebrated Christmas Eve together in 1914, drinking schapps together. One year later, ad hoc ceasefires took place again, this time in northern France. No man’s land was suddenly transformed into ‘a country fair’ as lively bartering began for schnapps, cigarettes, coffee, uniform buttons and other trinkets. More worryingly for their superiors, the soldiers sang the Internationale.

Yet socialist hopes that soldiers would ultimately repudiate their national loyalties for the sake of international brotherhood were proven to be futile. Christmas Truce was almost the last hurrah of a bygone era; as the war went on, mutual hatred grew, expunging the common origins and predicament of the combatants. War, too, has lost its mystique; soon, only fools would celebrate it or enter it with excited patriotic fervor. After August 1914, when thousands of red-trousered Frenchmen and white-gloved officers in full dress and plumes were decimated by German machine guns, France eschewed her pride and switched to neutral-colored service uniforms — the last world power to do so. Soon, there will be no more sabres and Sam Browne belts, no more centuries-old habits of chivalry, no more leaving civilians out of war.

via:

hat tip:

Wednesday, March 30, 2011

What Love Looks Like

Damian Aspinall had brought up Kwibi, a gorilla, at Howletts Wild Animal Park in England. When Kwibi was 5 years old, he was brought to a million-acres reserve in West Africa, and adapted to life there.

Five years later, when Kwibi was ten, Aspinall went to West Africa to see his old friend, who had attacked the last two people he had encountered.

Aspinall takes a boat up the river to find Kwibi.

If you don't have time for the four minutes of the video, then go to the 3-minute mark.

Microsoft’s Odd Couple

It’s 1975 and two college dropouts are racing to create software for a new line of “hobbyist” computers. The result? A company called “Micro-Soft”—now the fifth-most-valuable corporation on earth. In an adaptation from his memoir, the author tells the story of his partnership with high-school classmate Bill Gates, until its dramatic ending in 1983.

[ed. note. This excerpt from a memoir by Paul Allen about the birth of Microsoft sounds eerily similar to that of another recent tech behemoth -- Facebook]by Paul Allen

The Teletype made a terrific racket, a mix of low humming, the Gatling gun of the paper-tape punch, and the ka-chacko-whack of the printer keys. The room’s walls and ceiling were lined with white corkboard for soundproofing. But though it was noisy and slow, a dumb remote terminal with no display screen or lowercase letters, the ASR-33 was also state-of- the-art. I was transfixed. I sensed that you could do things with this machine.

The Teletype made a terrific racket, a mix of low humming, the Gatling gun of the paper-tape punch, and the ka-chacko-whack of the printer keys. The room’s walls and ceiling were lined with white corkboard for soundproofing. But though it was noisy and slow, a dumb remote terminal with no display screen or lowercase letters, the ASR-33 was also state-of- the-art. I was transfixed. I sensed that you could do things with this machine.That year, 1968, would be a watershed in matters digital. In March, Hewlett-Packard introduced the first programmable desktop calculator. In June, Robert Dennard won a patent for a one-transistor cell of dynamic random-access memory, or DRAM, a new and cheaper method of temporary data storage. In July, Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore co-founded Intel Corporation. In December, at the legendary “mother of all demos” in San Francisco, the Stanford Research Institute’s Douglas Engelbart showed off his original versions of a mouse, a word processor, e-mail, and hypertext. Of all the epochal changes in store over the next two decades, a remarkable number were seeded over those 10 months: cheap and reliable memory, a graphical user interface, a “killer” application, and more.

It’s hard to convey the excitement I felt when I sat down at the Teletype. With my program written out on notebook paper, I’d type it in on the keyboard with the paper-tape punch turned on. Then I’d dial into the G.E. computer, wait for a beep, log on with the school’s password, and hit the Start button to feed the paper tape through the reader, which took several minutes.

At last came the big moment. I’d type “RUN,” and soon my results printed out at 10 characters per second—a glacial pace next to today’s laser printers, but exhilarating at the time. It would be quickly apparent whether my program worked; if not, I’d get an error message. In either case, I’d quickly log off to save money. Then I’d fix any mistakes by advancing the paper tape to the error and correcting it on the keyboard while simultaneously punching a new tape—a delicate maneuver nowadays handled by a simple click of a mouse and a keystroke. When I achieved a working program, I’d secure it with a rubber band and stow it on a shelf.

Soon I was spending every lunchtime and free period around the Teletype with my fellow aficionados. Others might have found us eccentric, but I didn’t care. I had discovered my calling. I was a programmer.

One day early that fall, I saw a gangly, freckle-faced eighth-grader edging his way into the crowd around the Teletype, all arms and legs and nervous energy. He had a scruffy-preppy look: pullover sweater, tan slacks, enormous saddle shoes. His blond hair went all over the place. You could tell three things about Bill Gates pretty quickly. He was really smart. He was really competitive; he wanted to show you how smart he was. And he was really, really persistent. After that first time, he kept coming back. Many times he and I would be the only ones there.

Read more:

photo credit and additional article:

Cesium Fallout from Fukushima Already Rivals Chernobyl

As I’ve previously noted, many experts say that the Fukushima plants will keep on leaking for months. See this and this.

And the amount of radioactive fuel at Fukushima dwarfs Chernobyl.

As the New York Times notes, radioactive cesium is the main danger from the Japanese nuclear accident:

Over the long term, the big threat to human health is cesium-137, which has a half-life of 30 years.So it is bad news indeed that, as reported by New Scientist, cesium fallout from Fukushima already rivals Chernobyl:

At that rate of disintegration, John Emsley wrote in “Nature’s Building Blocks” (Oxford, 2001), “it takes over 200 years to reduce it to 1 percent of its former level.”

It is cesium-137 that still contaminates much of the land in Ukraine around the Chernobyl reactor.

***

Cesium-137 mixes easily with water and is chemically similar to potassium. It thus mimics how potassium gets metabolized in the body and can enter through many foods, including milk.

Radioactive caesium and iodine has been deposited in northern Japan far from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, at levels that were considered highly contaminated after Chernobyl.While Japan has been exposed to very high levels of cesium, so far, the levels of cesium in other parts of the world appear to be relatively low.

The readings were taken by the Japanese science ministry, MEXT, and reveal high levels of caesium-137 and iodine-131 outside the 30-kilometre evacuation zone, mostly to the north-north-west.

***

After the 1986 Chernobyl accident, the most highly contaminated areas were defined as those with over 1490 kilobecquerels (kBq) of caesium per square metre. Produce from soil with 550 kBq/m2 was destroyed.

People living within 30 kilometres of the plant have evacuated or been advised to stay indoors. Since 18 March, MEXT has repeatedly found caesium levels above 550 kBq/m2 in an area some 45 kilometres wide lying 30 to 50 kilometres north-west of the plant. The highest was 6400 kBq/m2, about 35 kilometres away, while caesium reached 1816 kBq/m2 in Nihonmatsu City and 1752 kBq/m2 in the town of Kawamata, where iodine-131 levels of up to 12,560 kBq/m2 have also been measured. “Some of the numbers are really high,” says Gerhard Proehl, head of assessment and management of environmental releases of radiation at the International Atomic Energy Agency.

And see this.

But anyone who believes that Fukushima cannot possibly become as bad as Chernobyl has no idea what they are talking about.

via:

Letting Go

by Atul Gawande

Sara Thomas Monopoli was pregnant with her first child when her doctors learned that she was going to die. It started with a cough and a pain in her back. Then a chest X-ray showed that her left lung had collapsed, and her chest was filled with fluid. A sample of the fluid was drawn off with a long needle and sent for testing. Instead of an infection, as everyone had expected, it was lung cancer, and it had already spread to the lining of her chest. Her pregnancy was thirty-nine weeks along, and the obstetrician who had ordered the test broke the news to her as she sat with her husband and her parents. The obstetrician didn’t get into the prognosis—she would bring in an oncologist for that—but Sara was stunned. Her mother, who had lost her best friend to lung cancer, began crying.

Sara Thomas Monopoli was pregnant with her first child when her doctors learned that she was going to die. It started with a cough and a pain in her back. Then a chest X-ray showed that her left lung had collapsed, and her chest was filled with fluid. A sample of the fluid was drawn off with a long needle and sent for testing. Instead of an infection, as everyone had expected, it was lung cancer, and it had already spread to the lining of her chest. Her pregnancy was thirty-nine weeks along, and the obstetrician who had ordered the test broke the news to her as she sat with her husband and her parents. The obstetrician didn’t get into the prognosis—she would bring in an oncologist for that—but Sara was stunned. Her mother, who had lost her best friend to lung cancer, began crying.

The doctors wanted to start treatment right away, and that meant inducing labor to get the baby out. For the moment, though, Sara and her husband, Rich, sat by themselves on a quiet terrace off the labor floor. It was a warm Monday in June, 2007. She took Rich’s hands, and they tried to absorb what they had heard. Monopoli was thirty-four. She had never smoked, or lived with anyone who had. She exercised. She ate well. The diagnosis was bewildering. “This is going to be O.K.,” Rich told her. “We’re going to work through this. It’s going to be hard, yes. But we’ll figure it out. We can find the right treatment.” For the moment, though, they had a baby to think about.

“So Sara and I looked at each other,” Rich recalled, “and we said, ‘We don’t have cancer on Tuesday. It’s a cancer-free day. We’re having a baby. It’s exciting. And we’re going to enjoy our baby.’ ” On Tuesday, at 8:55 P.M., Vivian Monopoli, seven pounds nine ounces, was born. She had wavy brown hair, like her mom, and she was perfectly healthy.

The next day, Sara underwent blood tests and body scans. Dr. Paul Marcoux, an oncologist, met with her and her family to discuss the findings. He explained that she had a non-small cell lung cancer that had started in her left lung. Nothing she had done had brought this on. More than fifteen per cent of lung cancers—more than people realize—occur in non-smokers. Hers was advanced, having metastasized to multiple lymph nodes in her chest and its lining. The cancer was inoperable. But there were chemotherapy options, notably a relatively new drug called Tarceva, which targets a gene mutation commonly found in lung cancers of female non-smokers. Eighty-five per cent respond to this drug, and, Marcoux said, “some of these responses can be long-term.”

Words like “respond” and “long-term” provide a reassuring gloss on a dire reality. There is no cure for lung cancer at this stage. Even with chemotherapy, the median survival is about a year. But it seemed harsh and pointless to confront Sara and Rich with this now. Vivian was in a bassinet by the bed. They were working hard to be optimistic. As Sara and Rich later told the social worker who was sent to see them, they did not want to focus on survival statistics. They wanted to focus on “aggressively managing” this diagnosis.

This is the moment in Sara’s story that poses a fundamental question for everyone living in the era of modern medicine: What do we want Sara and her doctors to do now? Or, to put it another way, if you were the one who had metastatic cancer—or, for that matter, a similarly advanced case of emphysema or congestive heart failure—what would you want your doctors to do?

The issue has become pressing, in recent years, for reasons of expense. The soaring cost of health care is the greatest threat to the country’s long-term solvency, and the terminally ill account for a lot of it. Twenty-five per cent of all Medicare spending is for the five per cent of patients who are in their final year of life, and most of that money goes for care in their last couple of months which is of little apparent benefit.

Spending on a disease like cancer tends to follow a particular pattern. There are high initial costs as the cancer is treated, and then, if all goes well, these costs taper off. Medical spending for a breast-cancer survivor, for instance, averaged an estimated fifty-four thousand dollars in 2003, the vast majority of it for the initial diagnostic testing, surgery, and, where necessary, radiation and chemotherapy. For a patient with a fatal version of the disease, though, the cost curve is U-shaped, rising again toward the end—to an average of sixty-three thousand dollars during the last six months of life with an incurable breast cancer. Our medical system is excellent at trying to stave off death with eight-thousand-dollar-a-month chemotherapy, three-thousand-dollar-a-day intensive care, five-thousand-dollar-an-hour surgery. But, ultimately, death comes, and no one is good at knowing when to stop.

Read more:

Tuesday, March 29, 2011

The Dark Side of Soy

by Mary Vance Terrain

by Mary Vance Terrain As someone who is conscious of her health, I spent 13 years cultivating a vegetarian diet. I took time to plan and balance meals that included products such as soy milk, soy yogurt, tofu, and Chick'n patties. I pored over labels looking for words I couldn't pronounce--occasionally one or two would pop up. Soy protein isolate? Great! They've isolated the protein from the soybean to make it more concentrated. Hydrolyzed soy protein? I never successfully rationalized that one, but I wasn't too worried. After all, in 1999 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved labeling I found on nearly every soy product I purchased: 'Diets low in saturated fat and cholesterol that include 25 grams of soy protein a day may reduce the risk of heart disease.' Soy ingredients weren't only safe--they were beneficial.

After years of consuming various forms of soy nearly every day, I felt reasonably fit, but somewhere along the line I'd stopped menstruating. I couldn't figure out why my stomach became so upset after I ate edamame or why I was often moody and bloated. It didn't occur to me at the time to question soy, heart protector and miracle food.

When I began studying holistic health and nutrition, I kept running across risks associated with eating soy. Endocrine disruption? Check. Digestive problems? Check. I researched soy's deleterious effects on thyroid, fertility, hormones, sex drive, digestion, and even its potential to contribute to certain cancers. For every study that proved a connection between soy and reduced disease risk another cropped up to challenge the claims. What was going on?

'Studies showing the dark side of soy date back 100 years,' says clinical nutritionist Kaayla Daniel, author of The Whole Soy Story (New Trends, 2005). 'The 1999 FDA-approved health claim pleased big business, despite massive evidence showing risks associated with soy, and against the protest of the FDA's own top scientists. Soy is a $4 billion [U.S.] industry that's taken these health claims to the bank.' Besides promoting heart health, the industry says, soy can alleviate symptoms associated with menopause, reduce the risk of certain cancers, and lower levels of LDL, the 'bad' cholesterol.

Class Warfare: Fire The Rich

by David Macaray

by David MacarayNot only has the so-called trickle-down theory of economics been revealed to be a cruel hoax, but most of the good industrial jobs have left the country, the middle class has been eviscerated, the wealthiest Americans (even in the wake of the recession) have quintupled their net worth, and polls show that upwards of 70 percent of the American public feel the country is “going down the wrong track.”

No jobs, no prospects, no leverage, no short-term solutions, no long-term plans, no big ideas to save us. While the bottom four-fifths struggle to stay afloat, and the upper one-fifth cautiously tread water, the top 1 percent continue to accumulate wealth at a staggering rate.

Thanks to the global engine, there are now more than a thousand billionaires. Oligarchies, “client-state” capitalism, wanton deregulation, CEOs earning monster salaries, corporations receiving taxpayer welfare, and half the U.S. Congress boasting of being millionaires. Meanwhile, personal debt in the United States continues to soar, one person in ten is out of work, and food stamp usage sets new records every month.

Yet even with near-record unemployment, the Department of Commerce reported in November 2010 that U.S. companies just had their best quarter . . . ever. Businesses recorded profits at an annual rate of $1.66 trillion in the third quarter of 2010, which is the highest rate (in non-inflation-adjusted figures) since the government began keeping records more than 60 years ago. Shrinking incomes, fewer jobs . . . but bigger corporate profits. Not a good sign.

Will Cell Phones Replace Wallets?

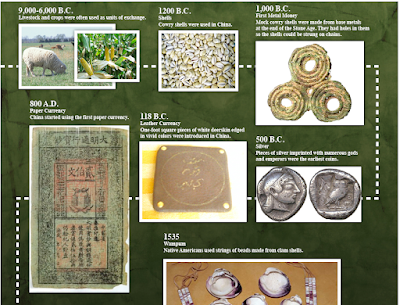

The history of money and the emergence of Near Field Communication (NFC) technology. Click on the graphic for a full size image (this is roughly 20%):

via:

via:

Humble Abode

With breathtaking views of the Amandan Sea, this stunning six-bedroom villa designed by Original Vision is a sight to behold. Built into a dramatic granite rock face and situated on the exclusive Millionaire’s Mile, the incredible Villa Amanzi in Phuket, Thailand sleeps up to 12 guests with daily rates of $2,000 – $4,500 per day.

Tracking the Migration of the Common Loon

December 2010: The U.S. Geological Survey hosts a website where you can track the migration of common loons (Gavia immer)from the Upper Midwest and Northeast to the Gulf and Southeast U.S. Individual birds are tracked using satellite telemetry.

If you want to explore the website, it's at this link.

[ed. note. very cool application, check it out]

via:

V-22 Osprey Tiltrotor

Wikipedia: The Osprey is the world's first production tiltrotor aircraft, with one three-bladed proprotor, turboprop engine, and transmission nacelle mounted on each wingtip. It is classified as a powered lift aircraft by the Federal Aviation Administration. For takeoff and landing, it typically operates as a helicopter with the nacelles vertical and rotors horizontal. Once airborne, the nacelles rotate forward 90° in as little as 12 seconds for horizontal flight, converting the V-22 to a more fuel-efficient, higher-speed turboprop airplane. STOL rolling-takeoff and landing capability is achieved by having the nacelles tilted forward up to 45°. For compact storage and transport, the V-22's wing rotates to align, front-to-back, with the fuselage. The proprotors can also fold in a sequence taking 90 seconds. Composite materials make up 43% of the V-22's airframe. The proprotors blades also use composites.

The V-22's development process has been long and controversial, partly due to its large cost increases. The V-22's development budget was first planned for $2.5 billion in 1986, then increased to a projected $30 billion in 1988. As of 2008, $27 billion have been spent on the Osprey program and another $27.2 billion will be required to complete planned production numbers by the end of the program.

The aircraft is incapable of autorotation, and is therefore unable to land safely in helicopter mode if both engines fail. A director of the Pentagon's testing office in 2005 said that if the Osprey loses power while flying like a helicopter below 1,600 feet (490 m), emergency landings "are not likely to be survivable". But Captain Justin (Moon) McKinney, a V-22 pilot, says there is an alternative, "We can turn it into a plane and glide it down, just like a C-130". A complete loss of power would require the failure of both engines, as one engine can power both proprotors via interconnected drive shafts. While vortex ring state (VRS) contributed to a deadly V-22 accident, the aircraft is less susceptible to the condition than conventional helicopters based on flight testing. But a GAO report stated the V-22 to be "less forgiving than conventional helicopters" during this phenomenon. In addition, several test flights to explore the V-22's VRS characteristics in greater detail were canceled. The Marines now train new pilots in the recognition of and recovery from VRS and have instituted operational envelope limits and instrumentation to help pilots avoid VRS conditions.

With the first combat deployment of the MV-22 in October 2007, Time Magazine ran an article condemning the aircraft as unsafe, overpriced, and completely inadequate. The Marine Corps, responded with the assertion that much of the article's data were dated, obsolete, inaccurate, and reflected expectations that ran too high for any new field of aircraft.

via:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)