Rolling In The Deep

Sunday, June 12, 2011

You Blow My Mind. Hey, Mickey!

by John Jeremiah Sullivan

One night my wife, M. J., said I should prepare to Disney. It wasn’t presented as a question or even as something to waste time thinking about, just to brace for, because it was happening. We have some old friends, Trevor and Shell (short for Michelle), and they have a girl, Flora, 5, who is only a year older than our daughter, Mimi. The girls grew up thinking of each other as cousins and get along beautifully. Shell and Trevor also have a younger son, Lil’ Dog. He possesses a real, dignified-sounding name, but his grandparents are the only people I’ve ever heard call him that. All his life he has been Lil’ Dog. The nickname didn’t come about in any special way. There’s no story attached. It was as if, at the moment of birth, the boy himself spoke and chose this moniker. When you look at him, something in him makes you want to say, “Lil’ Dog.” He’s a tiny, sandy-haired, muscular guy, with a goofy, lolling grin, who’s always about twice as heavy when you pick him up as you thought he was going to be.

One night my wife, M. J., said I should prepare to Disney. It wasn’t presented as a question or even as something to waste time thinking about, just to brace for, because it was happening. We have some old friends, Trevor and Shell (short for Michelle), and they have a girl, Flora, 5, who is only a year older than our daughter, Mimi. The girls grew up thinking of each other as cousins and get along beautifully. Shell and Trevor also have a younger son, Lil’ Dog. He possesses a real, dignified-sounding name, but his grandparents are the only people I’ve ever heard call him that. All his life he has been Lil’ Dog. The nickname didn’t come about in any special way. There’s no story attached. It was as if, at the moment of birth, the boy himself spoke and chose this moniker. When you look at him, something in him makes you want to say, “Lil’ Dog.” He’s a tiny, sandy-haired, muscular guy, with a goofy, lolling grin, who’s always about twice as heavy when you pick him up as you thought he was going to be.

Through family, Shell had come into some discount tickets, enough for the seven of us. It seemed not even a day passed between my getting a slight rumble of that news and finding myself at the wheel of the black Honda, headed south-southwest from North Carolina. For events to have actually moved this quickly is not far-fetched. M. J. often springs trips and appointments on me, in some cases literally overnight, knowing that if she removes the time factor, I won’t be able to generate bogus neurotic back-out plans. Many of the best vacation memories of my life I owe to these strategies, which prove again a useful principle for all couples: don’t try to change each other. Study and subvert each other.

The camper containing Shell, Trevor, Flora and Lil’ Dog moved south-southeast from Chattanooga. We were converging like lines on a graphing calculator. Unless you are very, very strong, the time will come when you Disney, and our time had come, unrolling like a glaring scroll in the form of I-95. It was a Saturday. The next day would be Father’s Day. This whole voyage, it turned out, was billed as a Father’s Day gift to me and Trevor, which in my case was like having been shot with a heavy barbiturate dart and bundled off to your own birthday party. Nonetheless I had little anxiety — a total lack of options will often produce a strange, free feeling. In the rearview mirror, Mimi practically strained her car-seat buckles with impatience. My highway thoughts passed through a curious phase of gratitude toward Walter Disney, as an individual, for having made possible such an intensity of childhood joy. Maybe Trevor felt the same about his little brood, hundreds of miles away, fewer each minute.

There’s something I should mention about Trevor, though I wouldn’t if it weren’t relevant to much of what came later, but he smokes a stupendous amount of weed. Think of a person who smokes a pack of cigarettes a day, that’s 20 cigarettes. Trevor smokes about that many joints, on a heavy day, the first one while he’s making coffee. And yet is highly functional in all social and professional senses, or almost all. I’ve definitely seen him muff some conversations. Still, 90 percent of the time he’s one of the sharpest and most interesting people I know. But to repeat: the brother is always, always high. We’re not talking about stuff your roommate grew in the side lot, either; this is California high-grade he obtains through a kind of nationwide medical-marijuana co-op, moving the legally obtained stuff out of California and into other states. It works the same as regular weed dealing, apparently, but you’re not supporting a criminal network. Except insofar as you are part of a criminal network. It is one of the many contradictions of living at a time when half the country thinks of weed as more innocent than alcohol and the other half thinks of it as a stepping stool to hard drugs. I needled Trevor once for details on his source. He said that, unfortunately, there was one rule: don’t tell your friends.

When Trevor and I became tight — as neighbors, in our early 20s — I was smoking a bit myself, almost competing with him. But when I hit 30, I backed up off it, as the song says. I never stopped liking the stuff or feeling that it benefited me, for that matter, but the habit was starting to make me dumb, and I was just humble enough by 30, I guess, to realize I hadn’t been born with enough cerebral ammunition to go voluntarily squandering any of it. Meanwhile Trevor stayed committed. And when we get together, a couple of times a year, I won’t lie, I fall prey to old patterns. Every so often it causes worry in my wife, especially since our daughter came along. Mostly I think she sees it as a useful pressure valve, which keeps me straighter and narrower the rest of the year. (Study, subvert: happiness = winner.)

Read more:

[ed. Terrific read, not just for the "being there" feeling it provides (...I've never been there), but the fascinating background story on how Disney World came about, its effect on Orlando, and the politics that made it happen.]

Something you learn rearing kids in this young millennium is that the word “Disney” works as a verb. As in, “Do you Disney?” Or, “Are we Disneying this year?” Technically a person could use the terms in speaking about the original Disneyland, in California, but this would be an anomalous usage. One goes to Disneyland and has a great time there, probably — I’ve never been — but one Disneys at the Walt Disney World Resort in Florida. There’s an implication of surrender to something enormous.

Something you learn rearing kids in this young millennium is that the word “Disney” works as a verb. As in, “Do you Disney?” Or, “Are we Disneying this year?” Technically a person could use the terms in speaking about the original Disneyland, in California, but this would be an anomalous usage. One goes to Disneyland and has a great time there, probably — I’ve never been — but one Disneys at the Walt Disney World Resort in Florida. There’s an implication of surrender to something enormous.

One night my wife, M. J., said I should prepare to Disney. It wasn’t presented as a question or even as something to waste time thinking about, just to brace for, because it was happening. We have some old friends, Trevor and Shell (short for Michelle), and they have a girl, Flora, 5, who is only a year older than our daughter, Mimi. The girls grew up thinking of each other as cousins and get along beautifully. Shell and Trevor also have a younger son, Lil’ Dog. He possesses a real, dignified-sounding name, but his grandparents are the only people I’ve ever heard call him that. All his life he has been Lil’ Dog. The nickname didn’t come about in any special way. There’s no story attached. It was as if, at the moment of birth, the boy himself spoke and chose this moniker. When you look at him, something in him makes you want to say, “Lil’ Dog.” He’s a tiny, sandy-haired, muscular guy, with a goofy, lolling grin, who’s always about twice as heavy when you pick him up as you thought he was going to be.

One night my wife, M. J., said I should prepare to Disney. It wasn’t presented as a question or even as something to waste time thinking about, just to brace for, because it was happening. We have some old friends, Trevor and Shell (short for Michelle), and they have a girl, Flora, 5, who is only a year older than our daughter, Mimi. The girls grew up thinking of each other as cousins and get along beautifully. Shell and Trevor also have a younger son, Lil’ Dog. He possesses a real, dignified-sounding name, but his grandparents are the only people I’ve ever heard call him that. All his life he has been Lil’ Dog. The nickname didn’t come about in any special way. There’s no story attached. It was as if, at the moment of birth, the boy himself spoke and chose this moniker. When you look at him, something in him makes you want to say, “Lil’ Dog.” He’s a tiny, sandy-haired, muscular guy, with a goofy, lolling grin, who’s always about twice as heavy when you pick him up as you thought he was going to be.Through family, Shell had come into some discount tickets, enough for the seven of us. It seemed not even a day passed between my getting a slight rumble of that news and finding myself at the wheel of the black Honda, headed south-southwest from North Carolina. For events to have actually moved this quickly is not far-fetched. M. J. often springs trips and appointments on me, in some cases literally overnight, knowing that if she removes the time factor, I won’t be able to generate bogus neurotic back-out plans. Many of the best vacation memories of my life I owe to these strategies, which prove again a useful principle for all couples: don’t try to change each other. Study and subvert each other.

The camper containing Shell, Trevor, Flora and Lil’ Dog moved south-southeast from Chattanooga. We were converging like lines on a graphing calculator. Unless you are very, very strong, the time will come when you Disney, and our time had come, unrolling like a glaring scroll in the form of I-95. It was a Saturday. The next day would be Father’s Day. This whole voyage, it turned out, was billed as a Father’s Day gift to me and Trevor, which in my case was like having been shot with a heavy barbiturate dart and bundled off to your own birthday party. Nonetheless I had little anxiety — a total lack of options will often produce a strange, free feeling. In the rearview mirror, Mimi practically strained her car-seat buckles with impatience. My highway thoughts passed through a curious phase of gratitude toward Walter Disney, as an individual, for having made possible such an intensity of childhood joy. Maybe Trevor felt the same about his little brood, hundreds of miles away, fewer each minute.

There’s something I should mention about Trevor, though I wouldn’t if it weren’t relevant to much of what came later, but he smokes a stupendous amount of weed. Think of a person who smokes a pack of cigarettes a day, that’s 20 cigarettes. Trevor smokes about that many joints, on a heavy day, the first one while he’s making coffee. And yet is highly functional in all social and professional senses, or almost all. I’ve definitely seen him muff some conversations. Still, 90 percent of the time he’s one of the sharpest and most interesting people I know. But to repeat: the brother is always, always high. We’re not talking about stuff your roommate grew in the side lot, either; this is California high-grade he obtains through a kind of nationwide medical-marijuana co-op, moving the legally obtained stuff out of California and into other states. It works the same as regular weed dealing, apparently, but you’re not supporting a criminal network. Except insofar as you are part of a criminal network. It is one of the many contradictions of living at a time when half the country thinks of weed as more innocent than alcohol and the other half thinks of it as a stepping stool to hard drugs. I needled Trevor once for details on his source. He said that, unfortunately, there was one rule: don’t tell your friends.

When Trevor and I became tight — as neighbors, in our early 20s — I was smoking a bit myself, almost competing with him. But when I hit 30, I backed up off it, as the song says. I never stopped liking the stuff or feeling that it benefited me, for that matter, but the habit was starting to make me dumb, and I was just humble enough by 30, I guess, to realize I hadn’t been born with enough cerebral ammunition to go voluntarily squandering any of it. Meanwhile Trevor stayed committed. And when we get together, a couple of times a year, I won’t lie, I fall prey to old patterns. Every so often it causes worry in my wife, especially since our daughter came along. Mostly I think she sees it as a useful pressure valve, which keeps me straighter and narrower the rest of the year. (Study, subvert: happiness = winner.)

Read more:

The Getaway Car

by Jonathan Raban

[ed. Tender, poignant memoir about letting go, and an excellent travelogue, too.]

For a long time now, I’ve been looking forward to this year with apprehension: 2011 is when my daughter, Julia, now 18, will undertake that very American rite of passage and “go away to college” — a phrase whose operative word is “away.” We live in Seattle, and in the Pacific Northwest, “collegeland,” as my daughter calls it, is centered in New England and New York, where most of her immediate friends will be going in September.

Though I’ve lived for 21 years in the U.S., I still have an Englishman’s stunted sense of distance. I think of 300 miles as a long journey, and all through last summer and fall, I would wake at 4 a.m. to sweat over the prospect of losing my daughter — my best companion, my anchor to the United States, the person with whom I’ve had the longest, most absorbing relationship of my adult life — to some unimaginably distant burg on the East Coast. So I was as elated as she was when she heard she’d been accepted by Stanford, her first choice. Same coast, same time zone — Within driving distance was the thought I clung to.

Interstate highways dull the reality of place and distance almost as effectively as jetliners do: I loathe their scary monotony. I wanted to make palpable the mileage that will stretch between us come September and feel on my own pulse the physical geography of our separation. We would take the coast road and mark out the wriggly, thousand-mile track that leads from my workroom to her future dorm in California.

Julia and I are old hands at taking road trips on her spring breaks, and stuffing our bags into the inadequate trunk of my two-seater convertible on a damp Sunday morning in early April, I sensed that this one might turn out to be our last. In the same car, or its identical predecessor, we’d driven to the Baja peninsula, the Grand Canyon, eastern Montana, British Columbia, on minor roads and with the top down, to open us as far as possible to the world we traveled through.

The rain that morning was the fine-sifted Northwest drizzle that grays this corner of the country for weeks on end; too heavy for the windshield wipers on intermittent and too light for slow, when the wipers skreak and whine on dry glass. To quicken us on our way, I steeled myself to take the Interstate as far as Olympia, the state capital, 60 miles to the southwest, from where we’d branch out to the coast. On the freeway, tire rumble and the kerchunk-kerchunk of our hard suspension’s rattling over expansion joints made conversation impossible, and the car felt as small as a pill bug, likely to be squashed flat by the next 18-wheeler. Julia wired herself to her iPod.

She was 3, going on 4, when her mother and I separated, and she could barely remember a time when she hadn’t commuted between two Seattle houses, twice a week, under the terms of the joint-custody agreement. First she moved with her stuffed bear, then with bear plus live dog; nowadays she traveled with so much stuff that she looked like an overladen packhorse when she staggered out the door with it. College offered her the promise of a life more secure and regular than any she had known since 1996 — an end to all that house-to-school-to-the-other-house gypsying that she managed with forbearing grace. Much as I feared her going away, I knew what a luxury it would be for her to have her books, clothes and bed in one room for the length of a college quarter.

Read more:

For a long time now, I’ve been looking forward to this year with apprehension: 2011 is when my daughter, Julia, now 18, will undertake that very American rite of passage and “go away to college” — a phrase whose operative word is “away.” We live in Seattle, and in the Pacific Northwest, “collegeland,” as my daughter calls it, is centered in New England and New York, where most of her immediate friends will be going in September.

Though I’ve lived for 21 years in the U.S., I still have an Englishman’s stunted sense of distance. I think of 300 miles as a long journey, and all through last summer and fall, I would wake at 4 a.m. to sweat over the prospect of losing my daughter — my best companion, my anchor to the United States, the person with whom I’ve had the longest, most absorbing relationship of my adult life — to some unimaginably distant burg on the East Coast. So I was as elated as she was when she heard she’d been accepted by Stanford, her first choice. Same coast, same time zone — Within driving distance was the thought I clung to.

Interstate highways dull the reality of place and distance almost as effectively as jetliners do: I loathe their scary monotony. I wanted to make palpable the mileage that will stretch between us come September and feel on my own pulse the physical geography of our separation. We would take the coast road and mark out the wriggly, thousand-mile track that leads from my workroom to her future dorm in California.

Julia and I are old hands at taking road trips on her spring breaks, and stuffing our bags into the inadequate trunk of my two-seater convertible on a damp Sunday morning in early April, I sensed that this one might turn out to be our last. In the same car, or its identical predecessor, we’d driven to the Baja peninsula, the Grand Canyon, eastern Montana, British Columbia, on minor roads and with the top down, to open us as far as possible to the world we traveled through.

The rain that morning was the fine-sifted Northwest drizzle that grays this corner of the country for weeks on end; too heavy for the windshield wipers on intermittent and too light for slow, when the wipers skreak and whine on dry glass. To quicken us on our way, I steeled myself to take the Interstate as far as Olympia, the state capital, 60 miles to the southwest, from where we’d branch out to the coast. On the freeway, tire rumble and the kerchunk-kerchunk of our hard suspension’s rattling over expansion joints made conversation impossible, and the car felt as small as a pill bug, likely to be squashed flat by the next 18-wheeler. Julia wired herself to her iPod.

She was 3, going on 4, when her mother and I separated, and she could barely remember a time when she hadn’t commuted between two Seattle houses, twice a week, under the terms of the joint-custody agreement. First she moved with her stuffed bear, then with bear plus live dog; nowadays she traveled with so much stuff that she looked like an overladen packhorse when she staggered out the door with it. College offered her the promise of a life more secure and regular than any she had known since 1996 — an end to all that house-to-school-to-the-other-house gypsying that she managed with forbearing grace. Much as I feared her going away, I knew what a luxury it would be for her to have her books, clothes and bed in one room for the length of a college quarter.

Read more:

Upside Down

by Ronald Brownstein

It’s hard to say this spring whether it’s more difficult for the class of 2011 to enter the labor force or for the class of 1967 to leave it.

It’s hard to say this spring whether it’s more difficult for the class of 2011 to enter the labor force or for the class of 1967 to leave it.

Students now finishing their schooling—the class of 2011—are confronting a youth unemployment rate above 17 percent. The problem is compounding itself as those collecting high school or college degrees jostle for jobs with recent graduates still lacking steady work. “The biggest problem they face is, they are still competing with the class of 2010, 2009, and 2008,” says Matthew Segal, cofounder of Our Time, an advocacy group for young people.

At the other end, millions of graying baby boomers—the class of 1967—are working longer than they intended because the financial meltdown vaporized the value of their homes and 401(k) plans. For every member of the millennial generation frustrated that she can’t start a career, there may be a baby boomer frustrated that he can’t end one.

Cumulatively, these forces are inverting patterns that have characterized the economy since Social Security and the spread of corporate pensions transformed retirement.

Read more:

Saturday, June 11, 2011

Advice Tip: Point Your Lips

...and look Senswell.

Times Change

by Jay Kernis

He is the subject of a documentary about his life, "The Most Dangerous Man in America," nominated for a 2010 Academy Award, which took its title from the words former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger used to describe Ellsberg in 1971.

In the 1960s, Ellsberg was a high-level Pentagon official, a former Marine commander who believed the American government was always on the right side. But while working for the administration of Lyndon Johnson, Ellsberg had access to a top-secret document that revealed senior American leaders, including several presidents, knew that the Vietnam War was an unwinnable, tragic quagmire.

In the 1960s, Ellsberg was a high-level Pentagon official, a former Marine commander who believed the American government was always on the right side. But while working for the administration of Lyndon Johnson, Ellsberg had access to a top-secret document that revealed senior American leaders, including several presidents, knew that the Vietnam War was an unwinnable, tragic quagmire.

Officially titled "United States-Viet Nam Relations, 1945-1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense,"–the Pentagon Papers, as they became known–also showed that the government had lied to Congress and the public about the progress of the war. In 1969, he photocopied the 7,000-page study and gave it to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. In, 1971, Ellsberg leaked all 7,000 pages to The Washington Post, and 18 other newspapers, including The New York Times, which published them.

Not long after, he surrendered to authorities and confessed to being the leaker. Ellsberg was charged as a spy. His trial, on twelve felony counts posing a possible sentence of 115 years, was dismissed on grounds of governmental misconduct against him. In April 1973, the court learned that Nixon had ordered his so-called "Plumbers Unit" to break into the office of Ellsberg's psychiatrist to steal documents they hoped might make the whistle-blower appear crazy. In May, more evidence of government illegal wiretapping was revealed. The charges against Ellsberg were dropped. This led to the convictions of several White House aides and figured in the impeachment proceedings against President Nixon.

Read more:

"Richard Nixon, if he were alive today, might take bittersweet satisfaction to know that he was not the last smart president to prolong unjustifiably a senseless, unwinnable war, at great cost in human life… He would probably also feel vindicated (and envious) that ALL the crimes he committed against me — which forced his resignation facing impeachment — are now legal."

Daniel Ellsburg, in an interview with CNN.He is the subject of a documentary about his life, "The Most Dangerous Man in America," nominated for a 2010 Academy Award, which took its title from the words former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger used to describe Ellsberg in 1971.

Officially titled "United States-Viet Nam Relations, 1945-1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense,"–the Pentagon Papers, as they became known–also showed that the government had lied to Congress and the public about the progress of the war. In 1969, he photocopied the 7,000-page study and gave it to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. In, 1971, Ellsberg leaked all 7,000 pages to The Washington Post, and 18 other newspapers, including The New York Times, which published them.

Not long after, he surrendered to authorities and confessed to being the leaker. Ellsberg was charged as a spy. His trial, on twelve felony counts posing a possible sentence of 115 years, was dismissed on grounds of governmental misconduct against him. In April 1973, the court learned that Nixon had ordered his so-called "Plumbers Unit" to break into the office of Ellsberg's psychiatrist to steal documents they hoped might make the whistle-blower appear crazy. In May, more evidence of government illegal wiretapping was revealed. The charges against Ellsberg were dropped. This led to the convictions of several White House aides and figured in the impeachment proceedings against President Nixon.

Read more:

A Dog's Life

by Felisa Rogers

As the Coney Island boardwalk gives way to textured cement, and traditional Coney Island haunts such as Ruby's and the Cha Cha celebrate their last summer in the shadow of forced demolition, it seems an opportune time to take a look at the history of Coney Island's most iconic emblem: the hot dog.

Although Coney Island is at the epicenter of hot dog history, the dog did not originate on the boardwalk. The lowbrow snack is the bastard American descendant of sausages brought to the New World by immigrants from Germany and Austria (hence the origin of a word that has been getting a lot of press lately: "wiener," which stems from the name of Austria's capital, Vienna, or Wien). Sausage vending was a relatively inexpensive home business for upwardly mobile immigrants, and by the 1860s, the strolling meat purveyors were a fixture of urban street scenes.

Although Coney Island is at the epicenter of hot dog history, the dog did not originate on the boardwalk. The lowbrow snack is the bastard American descendant of sausages brought to the New World by immigrants from Germany and Austria (hence the origin of a word that has been getting a lot of press lately: "wiener," which stems from the name of Austria's capital, Vienna, or Wien). Sausage vending was a relatively inexpensive home business for upwardly mobile immigrants, and by the 1860s, the strolling meat purveyors were a fixture of urban street scenes.

On September 1894, the Duluth News Tribune described a visit to Chicago:

As the Coney Island boardwalk gives way to textured cement, and traditional Coney Island haunts such as Ruby's and the Cha Cha celebrate their last summer in the shadow of forced demolition, it seems an opportune time to take a look at the history of Coney Island's most iconic emblem: the hot dog.

Although Coney Island is at the epicenter of hot dog history, the dog did not originate on the boardwalk. The lowbrow snack is the bastard American descendant of sausages brought to the New World by immigrants from Germany and Austria (hence the origin of a word that has been getting a lot of press lately: "wiener," which stems from the name of Austria's capital, Vienna, or Wien). Sausage vending was a relatively inexpensive home business for upwardly mobile immigrants, and by the 1860s, the strolling meat purveyors were a fixture of urban street scenes.

Although Coney Island is at the epicenter of hot dog history, the dog did not originate on the boardwalk. The lowbrow snack is the bastard American descendant of sausages brought to the New World by immigrants from Germany and Austria (hence the origin of a word that has been getting a lot of press lately: "wiener," which stems from the name of Austria's capital, Vienna, or Wien). Sausage vending was a relatively inexpensive home business for upwardly mobile immigrants, and by the 1860s, the strolling meat purveyors were a fixture of urban street scenes.On September 1894, the Duluth News Tribune described a visit to Chicago:

More numerous than the lunch wagon is the strolling salesman of "red hots." This individual clothed in ragged trousers, a white coat and cook's cap, and unlimited cheek, obstructs the night prowler at every corner. He carries a tank in which are swimming and sizzling hundreds of Frankforters or Wieners. These mysterious denizens of the steaming deep are sold for five cents, which modest charge includes an allowance of horseradish or some other tear-producing substance.Early frankfurters were prepared in small butcher shops or kitchens and probably featured a coarser grind of meat than does the average modern hot dog, which is the product of emulsifying technology. But it's hard to pinpoint "average." Even today, the definition of "hot dog" is vague: Hot dogs can be made of beef or pork or both, with or without casings. According to the Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink: "Most hot dogs are made from emulsified or finely chopped skeletal meats, but some contain organs and other 'variety' meats."

The Internet Is My Religion

Watch live streaming video from pdf2011 at livestream.com

I'm at the Personal Democracy Forum at NYU today, and the morning plenary has been a series of fascinating short talks. But one talk, by Jim Gilliam's "The Internet is My Religion," brought the house down. Jim worked in many early and influential Internet firms, went on to produce Robert Greenwald's extraordinary films, and do many other notable things. Among them was surviving two bouts of cancer and a double-lung transplant. The story of how he went from a Jerry Falwell born-again to an Internet advocate and film producer ended with a standing ovation and not a dry eye in the house. Watch this, please, I'd consider it a favor.

Jim Gilliam- The Future of Sharing

via:

Duh, Bor-ing

by Joseph Epstein

Somewhere I have read that boredom is the torment of hell that Dante forgot.–Albert Speer, Spandau: The Secret Diaries

Somewhere I have read that boredom is the torment of hell that Dante forgot.–Albert Speer, Spandau: The Secret Diaries

Unrequited love, as Lorenz Hart instructed us, is a bore, but then so are a great many other things: old friends gone somewhat dotty from whom it is too late to disengage, the important social-science-based book of the month, 95 percent of the items on the evening news, discussions about the Internet, arguments against the existence of God, people who overestimate their charm, all talk about wine, New York Times editorials, lengthy lists (like this one), and, not least, oneself.

Unrequited love, as Lorenz Hart instructed us, is a bore, but then so are a great many other things: old friends gone somewhat dotty from whom it is too late to disengage, the important social-science-based book of the month, 95 percent of the items on the evening news, discussions about the Internet, arguments against the existence of God, people who overestimate their charm, all talk about wine, New York Times editorials, lengthy lists (like this one), and, not least, oneself.Some people claim never to have been bored. They lie. One cannot be human without at some time or other having known boredom. Even animals know boredom, we are told, though they are deprived of the ability to complain directly about it. Some of us are more afflicted with boredom than others. Psychologists make the distinction between ordinary and pathological boredom; the latter doesn’t cause serious mental problems but is associated with them. Another distinction is that between situational boredom and existential boredom. Situational boredom is caused by the temporary tedium everyone at one time or another encounters: the dull sermon, the longueur-laden novel, the pompous gent extolling his prowess at the used-tire business. Existential boredom is thought to be the result of existence itself, caused by modern culture and therefore inescapable. Boredom even has some class standing, and was once felt to be an aristocratic attribute. Ennui, it has been said, is the reigning emotion of the dandy.

When bored, time slows drastically, the world seems logy and without promise, and reality itself can grow shadowy and vague. Truman Capote once described the novels of James Baldwin as “balls-achingly boring,” which conveys something of the agony of boredom yet is inaccurate—not about Baldwin’s novels, which are no stroll around the Louvre, but about the effect of boredom itself. Boredom is never so clearly localized. The vagueness of boredom, its vaporousness and its torpor, is part of its mild but genuine torment.

Boredom is often less pervasive in simpler cultures. One hears little of boredom among the pygmies or the Trobriand Islanders, whose energies are taken up with the problems of mere existence. Ironically, it can be most pervasive where a great deal of stimulation is available. Boredom can also apparently be aided by overstimulation, or so we are all learning through the current generation of children, who, despite their vast arsenal of electronic toys, their many hours spent before screens of one kind or another, more often than any previous generation register cries of boredom. Rare is the contemporary parent or grandparent who has not heard these kids, when presented with a project for relief of their boredom—go outside, read a book—reply, with a heavy accent on each syllable, “Bor-ing.”

Read more:

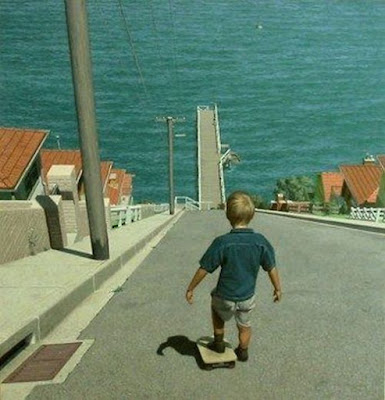

image credit:

Being Ernest

by John Walsh

by John Walsh Fifty years ago, in the early hours of Sunday 2 July, 1961, Ernest Hemingway, America's most celebrated writer and a titan of 20th-century letters, awoke in his house in the Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho, rose from his bed, taking care not to wake his wife Mary, unlocked the door of the storage room where he kept his firearms, and selected a double-barrelled shotgun with which he liked to shoot pigeons. He took it to the front of the house and, in the foyer, put the twin barrels against his forehead, reached down, pushed his thumb against the trigger and blew his brains out.

His death was timed at 7am. Witnesses who saw the body remarked that he had chosen from his wardrobe a favourite dressing gown that he called his "emperor's robe". They might have been reminded of the words of Shakespeare's Cleopatra, just before she applied the asp to her flesh: "Give me my robe. Put on my crown; I have immortal longings in me". His widow Mary told the media that it was an unfortunate accident, that Ernest had been cleaning one of his guns when it accidentally went off. The story was splashed on the front page of all American newspapers.

It took Mary Welsh Hemingway several months to admit that her husband's death was suicide; and it's taken nearly 50 years to piece together the reasons why this giant personality, this rumbustious man of action, this bullfighter, deep-sea fisherman, great white hunter, war hero, gunslinger and four-times-married, all-round tough guy, whom every red-blooded American male hero-worshipped, should do himself in. How could he? Why would he? Successive biographers – AE Hochtner, Carlos Baker, KS Lynn, AJ Monnier, Anthony Burgess – have chewed over the available facts, his restless travelling, his many amours, the peaks and troughs of his writing career. But eventually it took a psychiatrist from Houston, Texas, to hold up all the evidence to the light and announce his disturbing conclusions.

Read more:

Groupon Disaster

by Rocky Agrawal

"Groupon was the single worst decision I have ever made as a business owner."

“How much is your average sale here?”

“It’s about five dollars.”

That one question told me Jessie Burke had been sold an unsuitable product. Her average sale was $5 and her Groupon rep had convinced her to run a Groupon for $13.

I already knew how the story ended. Jessie had posted about her experience running a Groupon for Posies Cafe on her blog. She calls running a Groupon “the single worst decision I have ever made as a business owner thus far.” You can read the story in Jessie’s own words.

I wanted to drill deeper and get at the why. I sat with her for an extended conversation. This is only one business owner’s experience, but it is a story worth retelling.

Read more:

"Groupon was the single worst decision I have ever made as a business owner."

“How much is your average sale here?”

“It’s about five dollars.”

That one question told me Jessie Burke had been sold an unsuitable product. Her average sale was $5 and her Groupon rep had convinced her to run a Groupon for $13.

I already knew how the story ended. Jessie had posted about her experience running a Groupon for Posies Cafe on her blog. She calls running a Groupon “the single worst decision I have ever made as a business owner thus far.” You can read the story in Jessie’s own words.

I wanted to drill deeper and get at the why. I sat with her for an extended conversation. This is only one business owner’s experience, but it is a story worth retelling.

Read more:

Not Maid of Money

Lots of ink has been spilled on the high cost of the average American wedding ($26,984, according to theKnot.com’s 2010 survey), but it’s not just the father of bride who is feeling the pinch. As weddings become more elaborate, weekend-long affairs, often taking place in getaway locales (24 percent of nuptials are “destination weddings” according to the Knot), bridesmaids are shouldering larger costs as well.

In the past, bridesmaids were just expected to buy a dress and help throw a shower. Now, as women marry later in life, they often choose wedding attendants from different stages in their life, such as a younger sister, the high school BFF, college roommate and their closest colleague. Chances are the wedding will not take place locally for all of them, so a flight or hotel stay may be required for some. It’s no surprise that travel expenses make up one of the biggest components in the bridesmaid budget.

Pre-wedding festivities can also take a big bite. As seen in the movie Bridesmaids, showers can spiral out of control if one maid with expensive tastes decides to make it a catered affair. Bachelorette parties can snowball from a simple girls’ night out to an indulgent spa weekend or a jaunt to Vegas. For some die-hard wedding fans, it’s all worth it, but for the more budget-minded maids in the wedding party, it can bring a lot of stress to what’s supposed to be a happy occasion.

Here’s a look at where the cost come from, according to WeddingChannel.com, and some tips on how both brides and their attendants can keep money agony from souring their relationship, and the wedding day.

In the past, bridesmaids were just expected to buy a dress and help throw a shower. Now, as women marry later in life, they often choose wedding attendants from different stages in their life, such as a younger sister, the high school BFF, college roommate and their closest colleague. Chances are the wedding will not take place locally for all of them, so a flight or hotel stay may be required for some. It’s no surprise that travel expenses make up one of the biggest components in the bridesmaid budget.

Pre-wedding festivities can also take a big bite. As seen in the movie Bridesmaids, showers can spiral out of control if one maid with expensive tastes decides to make it a catered affair. Bachelorette parties can snowball from a simple girls’ night out to an indulgent spa weekend or a jaunt to Vegas. For some die-hard wedding fans, it’s all worth it, but for the more budget-minded maids in the wedding party, it can bring a lot of stress to what’s supposed to be a happy occasion.

Here’s a look at where the cost come from, according to WeddingChannel.com, and some tips on how both brides and their attendants can keep money agony from souring their relationship, and the wedding day.

[click image for larger graphic]

via:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)