Tuesday, January 31, 2012

America’s Confessor

Answering night-time calls at a suicide hotline in Washington DC some years ago, Frank Warren found himself using The Voice. Addressing callers’ problems and telling them where they might seek help, he noticed, was not nearly so important as adopting a certain tone: soothing, hypnotic, passive.

Nowadays, Warren regularly speaks before hundreds of people; he says he sometimes slips into The Voice at these public events, but from what I can tell he seems to talk this way all the time. Whether he is discussing one person’s trouble tuning in to a radio station, or another’s difficulty with childhood sexual abuse, he projects relentless and unflappable sympathy.

With narrow shoulders, grey hair, glasses and a shy smile, Warren, aged 47, looks like an extra from The Office—you can imagine him trying to fix a photocopier. He also bears a resemblance to Dr Drew, America’s most famous television therapist, and like Dr Drew, Warren has risen to prominence by providing a forum where people can air their most closely held (and at times shocking) secrets. Warren has become America’s secular confessor. The question is whether so many people should be entrusting him with their most private thoughts.

Back in 2004, Warren had a small business that managed medical documents and he was bored with it. To amuse himself in his spare time he devised a little project, inspired by a dream he’d had on holiday in Paris the year before. He printed a batch of postcards with brief instructions typed on them: write on a postcard a secret that you’ve never told anyone, design the card however you like, and send it anonymously to the address provided—Warren’s home in Maryland. Warren then handed out these postcards on the streets of Washington, DC and also tucked them into books in shops.

There was an immediate and extraordinary response. The postcards soon began to pour in—and when he launched PostSecret.com on 1st January 2005, the online traffic was heavy. He used the free, bare-bones Google blogging service for amateurs that he still employs today. An armload of web awards and a spate of press attention further boosted the site’s profile. When Warren sits down to pick the 20 postcards that he posts online each Sunday, he is often choosing from a week’s total of more than 1,000, many of which are intricate works of homespun art.

Warren’s house is in a well-kept, upmarket development in Germantown, about an hour’s drive from Washington DC where the suburbs give way to farmland. The postwoman who delivers to his address tells me with a laugh that at least working the route gives her job security. Her confidence is well founded. Independent data that Warren showed me reported 1.7m unique visitors to his site per week and the hit counter on the website has registered more than half a billion visits. There are now French, German, Portuguese, Spanish and Chinese versions of the site, some of which are unauthorised. PostSecretUK launched two years ago; it is not affiliated with the original site but credits it as its inspiration.

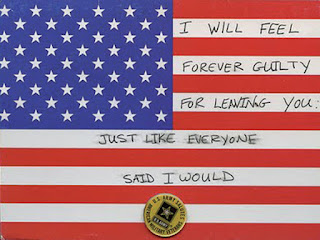

PostSecret.com provides readers with small, potent doses of humour, sadness and intrigue. “I would rather be hit than ignored,” says one. “I stare at my cleavage when I walk down stairs.” “My mom puts a star on the calendar for every day I haven’t cut myself. I don’t deserve 5 of those stars.” “Is it wrong to thank God every day for the man I’m having an affair with?” “He said my meat loaf wasn’t as good as his Mom’s. Now I put dog food in it. And SMILE when he eats it.” Next to a US Army pin, against the backdrop of an American flag: “I will feel forever guilty for leaving you just like everyone said I would.” Absurdity and heartbreak are often placed side by side, which makes the tone of the website both weird and powerful.

by Evan Hughes, Prospect | Read more:

Where does the anti-SOPA movement go next?

The last few weeks have witnessed a remarkable convergence of conflicts over copyright: the arrest of Megaupload mastermind “Kim Dotcom” in New Zealand, an unprecedented show of unity among Internet giants such as Wikipedia and Google to fight anti-piracy legislation in Congress, and similar protests in Poland against new copyright measures. In a world wracked by recession, war and revolution, a topic oft-dismissed by journalists as “arcane” — copyright — has surged to the top of the political agenda.

Indeed, supporters of anti-piracy legislation in Congress have confessed their ignorance of how copyright and the Internet work, saying the details were best left to the “nerds.” Lawmakers soon heard from the nerds, though, as an online insurgency spread to thwart the Stop Online Piracy Act, galvanizing opposition across the political spectrum in a novel way, from the Creative Commons left to right-wing blogs such as RedState. The campaign epitomizes a promising new turn in American politics, as critics of intellectual property law finally find an audience and, more important, the makings of a political constituency.

It was not always so, to say the least. Advocates of stronger copyright won an almost unbroken string of legislative and political triumphs since the early 1970s. A burst of piracy in the late 1960s, stimulated by the ease of recording on magnetic tape and the appearance of bootlegs of Bob Dylan and the Beatles, prompted Congress to extend protection to sound recordings in 1971. Thus began a continual expansion of the powers of copyright, with the term of protection extended from a maximum of 56 years to the life of the author plus 50 years in 1976, and another 20 years added in 1998.

Entertainment industries argued they needed protection. In a deindustrializing economy, they were job creators, net exporters of American goods. Disney reps in the early 1980s warned Congress that movie piracy would undercut jobs and tax revenue. With trademark bombast, Hollywood lobbyist Jack Valenti declared in 1982, “We are going to bleed and bleed and hemorrhage, unless this Congress at least protects one industry that is able to retrieve a surplus of trade and whose total future depends on its protection from the savagery of this machine.” (He was lobbying against the dreaded VCR.)

Meanwhile, opponents of stronger copyright had little to offer. Most were tape duplicators, who built their businesses on copying records and making mixtapes. These “pirates” urged Congress and state legislatures not to extend the length of copyright or bolster the power of rights-holders, but lawmakers paid them little attention.

Only with the rise of a new generation of copyright critics in the 1990s did a credible resistance emerge. Academics such as Lawrence Lessig, Kembrew McLeod and Siva Vaidhyanathan pointed out how excessive copyright protections allow corporate behemoths to push around small competitors while stifling creativity, such as mashups and sampling in hip-hop.

At first, this critique remained limited to a small constituency of tech activists, artists and academics. But Duke law professor James Boyle offered a prescient diagnosis of the movement’s problems in 1997, when he urged an “environmentalism for the net.” Environmentalism became one of America’s most vital and broad-based new political movements in the late 20th century, but its influence was initially limited. Scientists and nature lovers worried about environmental degradation, but they faced a difficult challenge persuading others that individual issues — a dam in a public park, suburban sprawl, pollution — were connected in a way that demanded broad public concern. The idea of the environment encompassed many issues that were different but related.

Critics of copyright, Boyle suggested, needed to theorize about the public domain in the same way nature lovers conceptualized the environment. They needed a framework to explain how intellectual property affected the people as a whole, and not just the librarians, musicians or teachers who might run up against the limits of copyright. For instance, a handful of polluters might benefit richly from easing clean air standards, while exposure to carcinogens hurts the broader population in a diffuse and indirect way. Similarly, lawmakers were reforming copyright law at the behest of those who stood most to profit from it — entertainment industries — but at the cost of impoverishing a public domain that most people thought little about.

by Alex Sayf Cummings, Salon | Read more:

Regrowing Scallions

If you like to cook with scallions (aka green onions or green shallots) did you know you can keep the white root ends from purchased scallions in a glass of water and they will regrow almost indefinitely?

Household weblog Homemade Serenity shares how scallion ends can regrow in in a glass of water. Just put the root ends in a glass of water and put that glass in a sunny window. After a few days you should be able to begin harvesting the green ends of the scallions. Make sure you change the water every so often and cut what you need with scissors before cooking.

You can see in the next picture how the roots grow and tangle in the cup of water. If you want to do this at home, it's simple. The next time you have green onions, don't throw away the white ends. Simply submerge them in a glass of water and place them in a sunny window. Your onions will begin to grow almost immediately and can be harvested almost indefinitely. We just use kitchen scissors to cut what we need for meals. I periodically empty out the water, rinse the roots off and give them fresh water.

Household weblog Homemade Serenity shares how scallion ends can regrow in in a glass of water. Just put the root ends in a glass of water and put that glass in a sunny window. After a few days you should be able to begin harvesting the green ends of the scallions. Make sure you change the water every so often and cut what you need with scissors before cooking.

You can see in the next picture how the roots grow and tangle in the cup of water. If you want to do this at home, it's simple. The next time you have green onions, don't throw away the white ends. Simply submerge them in a glass of water and place them in a sunny window. Your onions will begin to grow almost immediately and can be harvested almost indefinitely. We just use kitchen scissors to cut what we need for meals. I periodically empty out the water, rinse the roots off and give them fresh water.

Homeade Serenity via: Lifehacker

Monday, January 30, 2012

Made Better in Japan

It used be that the Japanese offered idiosyncratic takes on foreign things. White bread was transformed into shokupan, a Platonic ideal of fluffiness, aerated and feather-light in a way that made Wonder Bread seem dense. Pasta was almost always spaghetti, perfectly cooked al dente, but typically doused with cream sauce and often served with spicy codfish roe. Foreign imports here took on a life of their own, becoming something completely different and utterly Japanese.

During the robust economy of the '80s, Japan's exports ruled, and the country would import the best that money could buy from the rest of the globe, including Italian chefs and French sommeliers. Which made Japan an haute bourgeoisie heaven where luxury manufacturers from the West expected skyrocketing sales forever.

During the robust economy of the '80s, Japan's exports ruled, and the country would import the best that money could buy from the rest of the globe, including Italian chefs and French sommeliers. Which made Japan an haute bourgeoisie heaven where luxury manufacturers from the West expected skyrocketing sales forever.

But now 20-plus years of recession have killed that dream. Louis Vuitton sales are plummeting, and magnums of Dom Pérignon are no longer being uncorked at a furious pace. That doesn't mean the Japanese have turned away from the world. They've just started approaching it on their own terms, venturing abroad and returning home with increasingly more international tastes and much higher standards, realizing that the apex of bread making may not be Wonder Bread–style loaves, but pain à l'ancienne.

Japanese chefs are now cooking almost every cuisine imaginable, combining fidelity to the original with locally sourced products that complement or replace imports. When they prepare foreign foods, they're no longer asking themselves how they can make a dish more Japanese—or even more Italian, French or American. Instead they've moved on to a more profound and difficult challenge: how to make the whole dining experience better.

As a result of this quest, Japan has become the most culturally cosmopolitan country on Earth, a place where you can lunch at a bistro that serves 22 types of delicious and thoroughly Gallic terrines, shop for Ivy League–style menswear at a store that puts to shame the old-school shops of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and spend the evening sipping rare single malts in a serene space that boasts a collection of 12,000 jazz, blues and soul albums. The best of everything can be found here, and is now often made here: American-style fashion, haute French cuisine, classic cocktails, modern luxury hotels. It might seem perverse for a traveler to Tokyo to skip sukiyaki in favor of Neapolitan pizza, but just wait until he tastes that crust.

by Tom Downey, WSJ | Read more:

Photograph by Tung Walsh

During the robust economy of the '80s, Japan's exports ruled, and the country would import the best that money could buy from the rest of the globe, including Italian chefs and French sommeliers. Which made Japan an haute bourgeoisie heaven where luxury manufacturers from the West expected skyrocketing sales forever.

During the robust economy of the '80s, Japan's exports ruled, and the country would import the best that money could buy from the rest of the globe, including Italian chefs and French sommeliers. Which made Japan an haute bourgeoisie heaven where luxury manufacturers from the West expected skyrocketing sales forever.But now 20-plus years of recession have killed that dream. Louis Vuitton sales are plummeting, and magnums of Dom Pérignon are no longer being uncorked at a furious pace. That doesn't mean the Japanese have turned away from the world. They've just started approaching it on their own terms, venturing abroad and returning home with increasingly more international tastes and much higher standards, realizing that the apex of bread making may not be Wonder Bread–style loaves, but pain à l'ancienne.

Japanese chefs are now cooking almost every cuisine imaginable, combining fidelity to the original with locally sourced products that complement or replace imports. When they prepare foreign foods, they're no longer asking themselves how they can make a dish more Japanese—or even more Italian, French or American. Instead they've moved on to a more profound and difficult challenge: how to make the whole dining experience better.

As a result of this quest, Japan has become the most culturally cosmopolitan country on Earth, a place where you can lunch at a bistro that serves 22 types of delicious and thoroughly Gallic terrines, shop for Ivy League–style menswear at a store that puts to shame the old-school shops of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and spend the evening sipping rare single malts in a serene space that boasts a collection of 12,000 jazz, blues and soul albums. The best of everything can be found here, and is now often made here: American-style fashion, haute French cuisine, classic cocktails, modern luxury hotels. It might seem perverse for a traveler to Tokyo to skip sukiyaki in favor of Neapolitan pizza, but just wait until he tastes that crust.

by Tom Downey, WSJ | Read more:

Photograph by Tung Walsh

Smart Bullets

The US military is now using a rifle that reads like a science fiction novel: each bullet has a computer chip that calculates trajectory and then blows up when it is near its target, killing the enemy with shrapnel:

Smart coffee mugs, smart toilets, smart money, smart business cards, smart doorknobs.

via: Stowe Boyd

via The Economist

The XM25, as the new gun is known, weighs about 6kg (13lb) and fires a 25mm round. The trick is that instead of having to be aimed directly at the target, this round need only be aimed at a place in proximity to it. Once there, it explodes—just like Shrapnel’s original artillery shells—and the fragments kill the enemy. It knows when to explode because of a timed fuse. In Shrapnel’s shells this fuse was made of gunpowder. In the XM25 it is a small computer inside the bullet that monitors details of the projectile’s flight.

A handful of XM25s are now being tested in Afghanistan by the Americans. So far, they have been used on more than 200 occasions. Most of these fights ended quickly, and in America’s favour, according to Lieutenant-Colonel Shawn Lucas, who is in charge of the weapon’s field-testing programme. Indeed, the programme has been so successful that the army has ordered 36 more of the new rifles.

A new equaliser

Each rifle bullet is programmed, before it is fired, by a second computer in the rifle itself. To determine the distance to the target, the gunman shines a laser rangefinder attached to the rifle at whatever is shielding the enemy. If that enemy is in a ditch, a nearby object—a tree trunk behind or to the side of the ditch, perhaps—will do. Looking through the rifle’s telescopic sight, the gunman then estimates the distance from this object to the target. He presses a button near the trigger to add that value to (or subtract it from) the distance determined by the rangefinder.

When the round is fired, the internal computer counts the number of rotations it makes, to calculate the distance flown. The rifle’s muzzle velocity is 210 metres a second, which is the starting point for the calculation. When the computer calculates that the round has flown the requisite distance, it issues the instruction to detonate. The explosion creates a burst of shrapnel that is lethal within a radius of several metres (exact details are classified). And the whole process takes less than five seconds.

Just how the turn-counting fuse works is an even more closely guarded secret than the lethal radius—though judging by the number of failed attempts to hack into computers that might be expected to hold information about it, many people would dearly like to know. Certainly, the trick is not easy. An alternative design developed in South Korea, which clocks flight time rather than number of rotations, seems plagued by problems. Last year South Korea’s Agency of Defence Development halted production of trial versions of the K-11, as this rifle is called, and announced a redesign, following serious malfunctions.

The XM25, in contrast, appears to work well. It is accurate at ranges of up to 500 metres. That is almost as far as America’s main assault rifle, the M-16, can shoot conventional bullets with accuracy. More pertinently, it is nearly double the range of the AK-47, a rifle of Soviet design that is used by many insurgent groups. And according to Sergeant-Major Bernard McPherson, part of the XM25’s development programme in Virginia, it is receiving rave reviews from soldiers in the field.We are moving into a world where all designed objects will be connected, and calculating: everything is potentially smart, not just our phones.

Smart coffee mugs, smart toilets, smart money, smart business cards, smart doorknobs.

via: Stowe Boyd

Hollywood Fixer Opens His Little Black Book

Straight actors who wanted to pay for sex in the 1990s had Heidi Fleiss. Gay ones during the late 1940s and beyond apparently had Scotty Bowers.

His story has floated through moviedom’s clubby senior ranks for years: Back in a more golden age of Hollywood, a guy named Scotty, a former Marine, was said to have run a type of prostitution ring for gay and bisexual men in the film industry, including A-listers like Cary Grant, George Cukor and Rock Hudson, and even arranged sexual liaisons for actresses like Vivien Leigh and Katharine Hepburn.

“Old Hollywood people who have, shall we say, known him would tell me stories,” said Matt Tyrnauer, a writer for Vanity Fair and the director of the 2008 documentary “Valentino: The Last Emperor.” “But whenever I followed up on what would obviously be a great story, I was told, ‘Oh, he’ll never talk.’ ”

Now, he’s talking.

Mr. Bowers, 88, recalls his highly unorthodox life in a ribald memoir scheduled to be published by Grove Press on Feb. 14, “Full Service: My Adventures in Hollywood and the Secret Sex Lives of the Stars.” Written with Lionel Friedberg, an award-winning producer of documentaries, it is a lurid, no-detail-too-excruciating account of a sexual Zelig who (if you believe him) trawled an X-rated underworld for over three decades without getting caught.

“I’ve kept silent all these years because I didn’t want to hurt any of these people,” Mr. Bowers said recently over lemonade on his patio in the Hollywood Hills, where he lives in a cluttered bungalow with his wife of 27 years, Lois. “And I never saw the fascination. So they liked sex how they liked it. Who cares?”

He paused for a moment to scratch his collie, Baby, behind the ears. “I don’t need the money,” he continued. “I finally said yes because I’m not getting any younger and all of my famous tricks are dead by now. The truth can’t hurt them anymore.”

Twenty-six years after Hudson’s death from AIDS and more than four decades after “Hollywood Babylon” was first published, it will come as a surprise to no one that the images the movie factories created for stars of the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s — when Mr. Bowers was most active — were just that: images. The people who fed the world strait-laced cinema like “The Philadelphia Story” and perfect-family television like “I Love Lucy” were often quite the opposite of prudish in private.

At the same time, a lot of what Mr. Bowers has to say is pretty shocking. He claims, for instance, to have set Hepburn up with “over 150 different women.” Other stories in the 286-page memoir involve Spencer Tracy, Cole Porter, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor and socialites like the publisher Alfred A. Knopf. “If you believe him, and I do, he’s like the Kinsey Reports live and in living color,” said Mr. Tyrnauer, who recently completed a deal to make a documentary about Mr. Bowers.

by Brooks Barnes, NY Times | Read more:

Photo: Stephanie Diani

The Behavioral Sink

How do you design a utopia? In 1972, John B. Calhoun detailed the specifications of his Mortality-Inhibiting Environment for Mice: a practical utopia built in the laboratory. Every aspect of Universe 25—as this particular model was called—was pitched to cater for the well-being of its rodent residents and increase their lifespan. The Universe took the form of a tank, 101 inches square, enclosed by walls 54 inches high. The first 37 inches of wall was structured so the mice could climb up, but they were prevented from escaping by 17 inches of bare wall above. Each wall had sixteen vertical mesh tunnels—call them stairwells—soldered to it. Four horizontal corridors opened off each stairwell, each leading to four nesting boxes. That means 256 boxes in total, each capable of housing fifteen mice. There was abundant clean food, water, and nesting material. The Universe was cleaned every four to eight weeks. There were no predators, the temperature was kept at a steady 68°F, and the mice were a disease-free elite selected from the National Institutes of Health’s breeding colony. Heaven.

How do you design a utopia? In 1972, John B. Calhoun detailed the specifications of his Mortality-Inhibiting Environment for Mice: a practical utopia built in the laboratory. Every aspect of Universe 25—as this particular model was called—was pitched to cater for the well-being of its rodent residents and increase their lifespan. The Universe took the form of a tank, 101 inches square, enclosed by walls 54 inches high. The first 37 inches of wall was structured so the mice could climb up, but they were prevented from escaping by 17 inches of bare wall above. Each wall had sixteen vertical mesh tunnels—call them stairwells—soldered to it. Four horizontal corridors opened off each stairwell, each leading to four nesting boxes. That means 256 boxes in total, each capable of housing fifteen mice. There was abundant clean food, water, and nesting material. The Universe was cleaned every four to eight weeks. There were no predators, the temperature was kept at a steady 68°F, and the mice were a disease-free elite selected from the National Institutes of Health’s breeding colony. Heaven. Four breeding pairs of mice were moved in on day one. After 104 days of upheaval as they familiarized themselves with their new world, they started to reproduce. In their fully catered paradise, the population increased exponentially, doubling every fifty-five days. Those were the good times, as the mice feasted on the fruited plain. To its members, the mouse civilization of Universe 25 must have seemed prosperous indeed. But its downfall was already certain—not just stagnation, but total and inevitable destruction.

Calhoun’s concern was the problem of abundance: overpopulation. As the name Universe 25 suggests, it was not the first time Calhoun had built a world for rodents. He had been building utopian environments for rats and mice since the 1940s, with thoroughly consistent results. Heaven always turned into hell. They were a warning, made in a postwar society already rife with alarm over the soaring population of the United States and the world. Pioneering ecologists such as William Vogt and Fairfield Osborn were cautioning that the growing population was putting pressure on food and other natural resources as early as 1948, and both published bestsellers on the subject. The issue made the cover of Time magazine in January 1960. In 1968, Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb, an alarmist work suggesting that the overcrowded world was about to be swept by famine and resource wars. After Ehrlich appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson in 1970, his book became a phenomenal success. By 1972, the issue reached its mainstream peak with the report of the Rockefeller Commission on US Population, which recommended that population growth be slowed or even reversed.

But Calhoun’s work was different. Vogt, Ehrlich, and the others were neo-Malthusians, arguing that population growth would cause our demise by exhausting our natural resources, leading to starvation and conflict. But there was no scarcity of food and water in Calhoun’s universe. The only thing that was in short supply was space. This was, after all, “heaven”—a title Calhoun deliberately used with pitch-black irony. The point was that crowding itself could destroy a society before famine even got a chance. In Calhoun’s heaven, hell was other mice.

So what exactly happened in Universe 25? Past day 315, population growth slowed. More than six hundred mice now lived in Universe 25, constantly rubbing shoulders on their way up and down the stairwells to eat, drink, and sleep. Mice found themselves born into a world that was more crowded every day, and there were far more mice than meaningful social roles. With more and more peers to defend against, males found it difficult and stressful to defend their territory, so they abandoned the activity. Normal social discourse within the mouse community broke down, and with it the ability of mice to form social bonds. The failures and dropouts congregated in large groups in the middle of the enclosure, their listless withdrawal occasionally interrupted by spasms and waves of pointless violence. The victims of these random attacks became attackers. Left on their own in nests subject to invasion, nursing females attacked their own young. Procreation slumped, infant abandonment and mortality soared. Lone females retreated to isolated nesting boxes on penthouse levels. Other males, a group Calhoun termed “the beautiful ones,” never sought sex and never fought—they just ate, slept, and groomed, wrapped in narcissistic introspection. Elsewhere, cannibalism, pansexualism, and violence became endemic. Mouse society had collapsed.

by Will Wiles, Cabinet | Read more:

The Art of the Obituary

As obituaries editor of the Telegraph, I’m often asked if I find my job depressing. “Doesn’t it get you down?” people say in hushed, sympathetic tones, as though we were huddled together in the plushly upholstered confines of a Mayfair undertakers. “I mean, dealing with that relentless tide of death…” At which point I trot out a line well worn by those in my particular area of journalism: “Obituaries are not about death,” I insist. “They are a celebration of life.”

To illustrate my case, nothing more is required than a quick reference to the lives that have crossed my desk that day. How about the chap who traversed the Himalayas in a hovercraft? Or the spy who saved Churchill at the Tehran Conference? Or even the man who provided the voice for the puppet George (a “shy, pink and slightly camp hippopotamus”) on the children's television programme, Rainbow? In the obituary world, all human life is there – every barmy, uplifting scrap of it.

And if by some chance my morale was to falter for a second, then a moment’s reflection on the existence of Gay Kindersley, the amateur jump jockey who died last April, would restore the spirits. He wasn’t particularly famous, or the finest horseman of his generation, but as our obit recalled, Kindersley was “blessed with a barrel-load of charm”. It must have come in handy when he conducted the late Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother on a tour of his house at East Garston, only to step into a room with the royal visitor and find a couple in flagrante. “How nice,” she murmured. It’s hard to get too down in the dumps when presented with tales like that. And on the obits desk we are constantly presented with tales like that.

It seems that we are not the only ones to take this view. Next weekend London’s Southbank Centre is running a festival entitled “Death: Festival for the Living”. It aims to examine the rules and regulations, customs, traumas, idiosyncrasies, mysteries – and, yes, even joys – that surround mankind’s attitude to mortality.

According to Jude Kelly, the Southbank’s artistic director, it will be anything but melancholy. “I expect it to be a very jolly event,” she says. That sounds about right to me. After all, the most celebrated sketch in British comedy involves death (albeit of a certain Norwegian Blue parrot: “He’s a stiff. Bereft of life, he rests in peace. If you hadn’t nailed him to his perch he’d be pushing up the daisies!”) Visitors to newspaper offices have been known to inquire: “Who are those people over there, laughing?” only to receive the answer, “Ah, that’s the obits desk.”

We do laugh. And it is precisely because obituaries are about the juicy stuff of life that we do not usually mention the dry details about causes of death, unless they are strictly pertinent. When subjects have made a shockingly youthful departure, we will include a brief note to illuminate readers, who are naturally curious to learn what it was that killed a brilliant cellist, for example, just as she was reaching her prime.

Some of our counterparts on American newspapers extend this principle to the very elderly, and insist on noting that the centenarian hero they are obituarising was dispatched by congestive this, or complications of an infectious that. But we assume that our readers, if they feel the need to muse on what has done for a 117-year-old veteran of the silent film era, will assume that he or she has simply succumbed to old age. Or, as I’ve heard it put, “contracted an incurable case of death”. We all catch it in the end.

by Harry de Quetteville, The Telegraph | Read more:

Mask for 'Day of the Dead' (dia de los muertos) in Mexico Photo: Getty images

Sunday, January 29, 2012

The Alarming Outlook for Urban Water Scarcity

By 2020, California will face a shortfall of fresh water as great as the amount that all of its cities and towns together are consuming today.

When you look at the official US drought monitor map, you immediately see that many American cities may be in the wrong places for long-term water sustainability. In particullar, note the presence of “long-term,” severe-to-extreme drought conditions across most of Georgia, Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona.

It’s a very sobering set of facts, especially when you consider that essentially every high-growth part of the US is experiencing significant dryness. Now let’s look at a second map, this time world-wide:

This is not just a US Sun Belt problem but a major international problem. Here are a few facts and projections extracted from a very good summary of the issues by Jay Kimball on his blog 8020 Vision:

- By 2020, California will face a shortfall of fresh water as great as the amount that all of its cities and towns together are consuming today.

- By 2025, 1.8 billion people will live in conditions of absolute water scarcity, and 65 percent of the world’s population will be water stressed.

- In the US, 21 percent of agricultural irrigation is achieved by pumping groundwater at rates that exceed the water supplies ability to recharge.

- There are 66 golf courses in Palm Springs. On average, they each consume over a million gallons of water per day.

- The Ogalala aquifer, which stretches across 8 states and accounts for 40 percent of water used in Texas, will decline in volume by a staggering 52 percent between 2010 and 2060.

- Texans are probably pumping the Ogallala at about six times the rate of recharge.

The Caging of America

A prison is a trap for catching time. Good reporting appears often about the inner life of the American prison, but the catch is that American prison life is mostly undramatic—the reported stories fail to grab us, because, for the most part, nothing happens. One day in the life of Ivan Denisovich is all you need to know about Ivan Denisovich, because the idea that anyone could live for a minute in such circumstances seems impossible; one day in the life of an American prison means much less, because the force of it is that one day typically stretches out for decades. It isn’t the horror of the time at hand but the unimaginable sameness of the time ahead that makes prisons unendurable for their inmates. The inmates on death row in Texas are called men in “timeless time,” because they alone aren’t serving time: they aren’t waiting out five years or a decade or a lifetime. The basic reality of American prisons is not that of the lock and key but that of the lock and clock.

That’s why no one who has been inside a prison, if only for a day, can ever forget the feeling. Time stops. A note of attenuated panic, of watchful paranoia—anxiety and boredom and fear mixed into a kind of enveloping fog, covering the guards as much as the guarded. “Sometimes I think this whole world is one big prison yard, / Some of us are prisoners, some of us are guards,” Dylan sings, and while it isn’t strictly true—just ask the prisoners—it contains a truth: the guards are doing time, too. As a smart man once wrote after being locked up, the thing about jail is that there are bars on the windows and they won’t let you out. This simple truth governs all the others. What prisoners try to convey to the free is how the presence of time as something being done to you, instead of something you do things with, alters the mind at every moment. For American prisoners, huge numbers of whom are serving sentences much longer than those given for similar crimes anywhere else in the civilized world—Texas alone has sentenced more than four hundred teen-agers to life imprisonment—time becomes in every sense this thing you serve.

For most privileged, professional people, the experience of confinement is a mere brush, encountered after a kid’s arrest, say. For a great many poor people in America, particularly poor black men, prison is a destination that braids through an ordinary life, much as high school and college do for rich white ones. More than half of all black men without a high-school diploma go to prison at some time in their lives. Mass incarceration on a scale almost unexampled in human history is a fundamental fact of our country today—perhaps the fundamental fact, as slavery was the fundamental fact of 1850. In truth, there are more black men in the grip of the criminal-justice system—in prison, on probation, or on parole—than were in slavery then. Over all, there are now more people under “correctional supervision” in America—more than six million—than were in the Gulag Archipelago under Stalin at its height. That city of the confined and the controlled, Lockuptown, is now the second largest in the United States.

by Adam Gopnik, New Yorker | Read more:

Photograph by Steve Liss

Why the Clean Tech Boom Went Bust

John Doerr was crying. The billionaire venture capitalist had come to the end of his now-famous March 8, 2007, TED talk on climate change and renewable energy, and his emotions were getting the better of him. Doerr had begun by describing how his teenage daughter told him that it was up to his generation to fix global warming, since they had caused it. After detailing how the public and private sectors had so far failed at this, Doerr, who made his fortune investing early in companies that became some of Silicon Valley’s biggest names—Netscape, Amazon.com, and Google, among others—exhorted the audience and his peers (largely one and the same) to band together and transform the nation’s energy supply. “I really, really hope we multiply all of our energy, all of our talent, and all of our influence to solve this problem,” he said, falling silent as he fought back tears. “Because if we do, I can look forward to the conversation I’m going to have with my daughter in 20 years.”

As usual, Doerr’s timing was perfect. Just weeks earlier, Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth had won an Oscar for best documentary. (Gore is now a partner in Doerr’s green tech team at the VC firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers.) Interest in climate change had never been higher. And as the economy recovered from the dual shocks of the Internet bubble and 9/11, Doerr’s fellow Silicon Valley VCs were already looking to clean technology as the next big thing. What followed was yet another Silicon Valley gold rush, as the firms on Sand Hill Road were pulled along by the promise of new fortunes and the hope that they would be the ones to wean America off of fossil fuels. The entrepreneurs and tech investors who had transformed media and communications were ready to make Silicon Valley the Saudi Arabia of clean energy.

Never mind the fact that green technology had been struggling to achieve critical mass for decades. “You had folks who came in with the hubris to say, ‘I know these guys have been working on this for 50 years,’” says Andrew Beebe, chief commercial officer for Suntech, the Chinese solar manufacturer. “‘But I’ve got $50 million and I can blow the doors off this thing.’”

In 2005, VC investment in clean tech measured in the hundreds of millions of dollars. The following year, it ballooned to $1.75 billion, according to the National Venture Capital Association. By 2008, the year after Doerr’s speech, it had leaped to $4.1 billion. And the federal government followed. Through a mix of loans, subsidies, and tax breaks, it directed roughly $44.5 billion into the sector between late 2009 and late 2011. Avarice, altruism, and policy had aligned to fuel a spectacular boom.

Anyone who has heard the name Solyndra knows how this all panned out. Due to a confluence of factors—including fluctuating silicon prices, newly cheap natural gas, the 2008 financial crisis, China’s ascendant solar industry, and certain technological realities—the clean-tech bubble has burst, leaving us with a traditional energy infrastructure still overwhelmingly reliant on fossil fuels. The fallout has hit almost every niche in the clean-tech sector—wind, biofuels, electric cars, and fuel cells—but none more dramatically than solar.

by Juliet Eilperin, Wired | Read more:

Photo: Dan Forbes

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)