Your kitchen may not be the mirror of your soul, but it can produce a pretty accurate image of where you’ve landed on the time line of domesticity. Take a tour through it. You’ll find not only the food you eat (and don’t), and the objects with which you preserve, prepare, cook, and serve it, but, very likely, tucked away in the back of the highest cupboard, the abandoned paraphernalia of your mother’s or grandmother’s kitchen life. And if you think seriously about this, you will eventually start asking questions about what went on in other people’s kitchens during the twenty thousand years since one smart

Homo sapiens picked up a rock and ground a handful of wild barley into something he could eat—the most obvious being which came first, the food that sits in your fridge today or the technology, from the rock to the thermal immersion circulator, that got it there and puts it on the table.

I have two kitchens. For most of the year, I cook in an Upper West Side apartment, in Manhattan. It was designed in the eighteen-nineties and is probably best described as a landlord’s misguided attempt to lure tenants with horizontal evocations of the upstairs-downstairs life. The “public” rooms, meant to be seen and admired, were large and well proportioned. The “private” rooms, out of sight off a long back hall, were for the most part awkward and cramped, and perhaps the lowliest room on this totem pole of domestic status was the kitchen, where your cook, emerging each morning through the door of a tiny bedroom—in my apartment, it opened between the icebox and the sink—was expected to spend her waking hours. At the time, no one except, presumably, the cook cared that the kitchen was hot and smelly, or that she had to climb onto a chair or a stepladder to fetch the plates, or crouch on the floor to reach into the cabinets where she kept her pots and pans. Nobody else went in. There was room for only one chair, perhaps to discourage the cook from sitting down with the cook next door for a conversation, and no room at all for a table where she could have a meal.

This was the kitchen where I unpacked my own pots and pans in the nineteen-seventies—a mirror of somebody else’s moment in the saga of domestic life. There would be no company while I cooked, no friends sharing a glass of wine while they chopped the tomatoes for my pasta. Supper would mean the dining room, which remains so stately and demanding that I feel obliged to break out the family silver and the wedding china and lay the plates for a four-course dinner even when I’m eating alone with my husband. (Perhaps I should make a seating plan, or put out place cards.) More to the point, there was no way to expand my kitchen to accommodate my own moment—not, at any rate, without paying a plumber to move a century’s worth of corroding pipes. The cook’s bedroom became the cubbyhole study where I shut the door and write.

I am consoled, however, by my other kitchen. It is the “please come in” room of the Umbrian farmhouse where I work, and cook, in the summer—a much more satisfying image of the way I like to live. It was once occupied by cows. And while the house itself could be considered small—given the size of the peasant families that used to live together in four or five rooms above the animals—thestalla where I built my kitchen was enormous. The first things I bought for it, after the stove, the fridge, and the dishwasher went in, were an eleven-foot table, ten chairs, a pair of outsized armchairs, and an old stone fireplace wide enough for a side of pork. The shelves for my pots and pans are low and open. The front door, which leads directly into the room, is also open. My friends are welcome to my wine, my knives, and my chopping boards.

I was at the table in that companionable kitchen, sniffing the basil and garlic I had just ground to a mash for pesto in a mortar and pestle, when I started leafing through a book called “Consider the Fork: A History of How We Cook and Eat” (Basic), by the British writer Bee Wilson, and came upon a chapter called “Grind.” It was full of intriguing scholarship on the false starts and transformative successes without which there would have been no pesto on my table, but what intrigued me most was a paragraph on the subject of Wilson’s mortar and pestle. It was black granite, from Thailand, and much nicer to use, she said, than the white china variety, which set her teeth on edge “like chalk on a blackboard.” I felt a wave of kitchen kinship, first because the mortar and pestle I’d been using was also stone, but also because she called hers “an entirely superfluous piece of technology,” given the far easier ways of grinding and crushing available to her in a twenty-first-century Cambridge kitchen. She used it infrequently, she said, only when she had the time and the urge for the “bit of kitchen aromatherapy” that pounding together a pesto brings. In fact, she was terrified of getting it down from the shelf where, presumably, she kept her only-infrequently equipment. It was that heavy. She worried about dropping it on her foot. I imagined it stored at the same treacherous top-of-the-stepladder level where my paella pan, my mother’s biggest turkey platter, and my New York mortar and pestle, which is also stone and weighs nearly ten pounds, have been gathering dust for years. In New York, I share her terror. In Italy, where I can slide my mortar and pestle across a counter, brace myself, and move it to the table, the only thing that ever fell on my foot was a full bottle of Barolo, and it was three in the morning, I had been working late, and the fig tart in the oven was about to burn. (...)

Wilson remains engaging, and nowhere as deeply or as smoothly as in “Consider the Fork,” where the information she has to juggle is at once gastronomic, cultural, economic, and scientific. She will begin a disquisition on, say, why the Polynesians, who had been making clay cooking pots for a thousand years, abandoned clay when they arrived at the Marquesas Islands from Tonga and Samoa, a hundred or so years into the Christian era, and went back to cooking on hot stones; she will lead you through the various explanations, the most recent (and “radical,” she says) being that the yams, taro, breadfruit, and sweet potatoes that were their staples simply cooked better, or more efficiently, on hot stones than in pots; and then she will remind you that, short of ignorance, nostalgia, or necessity, there is always something mysterious about our choices and attachments, and do it with a homely story from her own kitchen—something recognizable.

by Jane Kramer, New Yorker |

Read more:

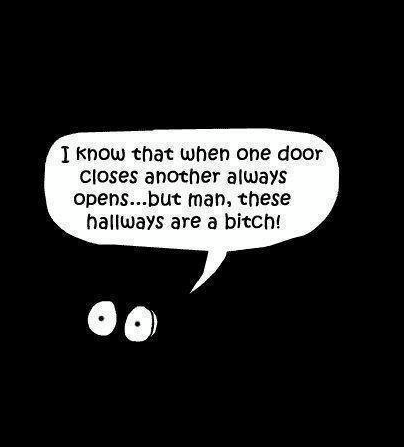

Illustration: Stephen Doyle.