Tuesday, September 24, 2013

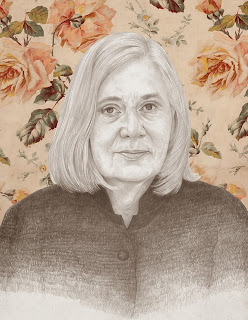

A Teacher and Her Student

[ed. Gilead, one of my favorite books.]

Marilynne Robinson was my fourth and final workshop instructor at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She is an intimidating intellectual presence—she once told us that to improve characterization, we should read Descartes. When I asked her to sign my copy of Gilead, she admitted she had recently become fascinated by ancient cuneiform script. But she is also generous and quick to laugh—when she offered to have us to her house for dinner, and I asked if we ought to bring food, she replied, “Or perhaps I will make some loaves and fishes appear!” Then she burst into giggles.

Marilynne Robinson was my fourth and final workshop instructor at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. She is an intimidating intellectual presence—she once told us that to improve characterization, we should read Descartes. When I asked her to sign my copy of Gilead, she admitted she had recently become fascinated by ancient cuneiform script. But she is also generous and quick to laugh—when she offered to have us to her house for dinner, and I asked if we ought to bring food, she replied, “Or perhaps I will make some loaves and fishes appear!” Then she burst into giggles.After receiving my MFA this May, I left Iowa believing that there’s no good way to be taught how to write, to tell a story. But there is also no denying that Marilynne has made me a better writer. Her demands are deceptively simple: to be true to human consciousness and to honor the complexities of the mind and its memory. Marilynne has said in other interviews that she doesn’t read much contemporary fiction because it would take too much of her time, but I suspect it’s also because she spends a fair amount of her mental resources on her students.

Our interview was held on one of the last days of the spring semester. The final traces of the bitter winter had disappeared, and light filled the classroom, which now felt empty with just the two of us. My two years at Iowa were over, and I selfishly wanted to stretch the interview for as long as possible.

You recently told the class you had discovered the ending to your new novel—or so you hoped. How does that happen for you? How do you know?

A lot of the experience of the novel—after the beginning—is being in the novel. You set yourself with a complex problem. If it’s a good problem or one that really engages you, then your mind works on it all the time. A novel by its nature is new. The great struggle, conscious or unconscious, is to make sure that it is new. That it actually has raised issues that deserve to be dealt with in their own terms. They’re not terms that you have seen elsewhere. It’s sort of like composing music. There are options that open and options that disappear, depending on how you develop the guidelines. You think about it over time. And then something will appear, something that is the most elegant response to the question that you’ve asked yourself. And it can absorb the most in terms of the complexities that you’ve created.

It struck me when you said we must “trust the peripheral vision of our mind.” It seems like a muscle in your body that you have to develop by training some other part of you.

It struck me when you said we must “trust the peripheral vision of our mind.” It seems like a muscle in your body that you have to develop by training some other part of you.

One reaches for analogies. I think it’s probably a lot like meditation—which I have never practiced. But from what I understand, it is a capacity that develops itself and that people who practice it successfully have access to aspects of consciousness that they would not otherwise have. They find these large and authoritative experiences. I think that, by the same discipline of introspection, you have access to a much greater part of your awareness than you would otherwise. Things come to mind. Your mind makes selections—this deeper mind—on other terms than your front-office mind. You will remember that once, in some time, in some place, you saw a person standing alone, and their posture suggested to you an enormous narrative around them. And you never spoke to them, you don’t know them, you were never within ten feet of them. But at the same time, you discover that your mind privileges them over something like the Tour d’Eiffel. There’s a very pleasant consequence of that, which is the most ordinary experience can be the most valuable experience. If you’re philosophically attentive you don’t need to seek these things out.

In a way, it seems more difficult. Like trying to look beautiful without makeup.

Harder in some cases than others. It is hard. Frankly, I think most people would think that if you look beautiful without makeup, you’re more truly beautiful than if you’re beautiful with makeup. Although that’s an argument in and of itself. If it were simply discipline, like learning to juggle, or something like that, that’s one thing. But it’s finding access into your life more deeply than you would otherwise. Consider this incredibly brief, incredibly strange experience that we have as this hypersensitive creature on a tiny planet in the middle of somewhere that looks a lot like nowhere. It’s assigning an appropriate value to the uniqueness of our situation and every individual situation.

by Thessaly La Force, Vice | Read more:

Image:Denise Nestor

It's Hip to be Hip, Too

This overarching identity dilemma is one born of aggressive social-media expressions, singing songs of ourselves each day and launching them unto the world to either coalesce in harmony with our peers, or to serve as a jarring counterpoint. Nowhere is this type of perpetually refreshing navel-gazing better illustrated than in our repeated investigation into the idea of hipsterhood. Barely a week goes by where we're not confronted by it—28 Signs You're A Hipster, What Was the Hipster?, and so on. More often than not, these come, for some reason, in the paper of record. This past weekend Steven Kurutz contemplated his own unexpected metamorphosis into this most picked-clean carcass of identity. “My initial surprise was replaced by a stark realization: as a 30-something skinnyish urban male there’s almost nothing I can wear that won’t make me look like a hipster,” he wrote, surprised to find himself enlisted into a community he never volunteered for. “Such is the pervasiveness of hipster culture that virtually every aspect of male fashion and grooming has been colonized.”

The versatility of the hipster signifier is what makes it such an empty avenue of exploration in goofy listicles and trend pieces while also engendering skeptics' frustration with its dogged refusal to go away. Public approval of hipsters is at 16 percent, according to a recent poll—Congress looks good in comparison. As Kurutz notes, almost everything can be woven into the hipster fabric now; it's a choose-your-own-ending story where every option leads to the same page, you standing there in some silly hat or other. White guy with a beard? Hipster. Black dude on a skateboard? Hipster. Just a sort-of-skinny cop? Hipster. Woman riding a bike? Hipster. You can play either a mandolin or a turntable and somehow still be a hipster. No rules! As a result, hipsters have become both an object of incessant scorn, but also endless fascination. When a hipster can be defined as anything, it also essentially means nothing—that's an undeniably appealing paradox to poke at.

One thing that seems universally agreed upon, however, as most of these types of pieces about what constitutes hipsterhood point out, and the thing that makes Kurutz such an obvious candidate for hipsterhood himself, is that no one—even the most self-evidently hipster among us—wants to admit to fitting the description. The only rule of hipster club is don't admit you're a member of hipster club. Nothing could be seen as less hip than actually wanting to align oneself with a superficial demo. That's exactly the wrong attitude, it seems to me, if we're to pin down this mercurial concept. The original hipster was someone who bucked the status quo and jumped out ahead of the curve. So, unlike Kurutz and the thousands who have come before him bending themselves into logical pretzels trying to shrug off the designation, I'd like affirm my hipsterhood—with pride.

by Luke O'Neil, Slate | Read more:

Image: Luke O'Neil

The Last Laugh

Norman Mailer went out running with Muhammad Ali one morning, a few days before the fight with George Foreman in Zaire. He asked me to go with him, but I thought of the long ride to Ali’s training camp at N’Sele in the darkness, and thumping along for five miles or so in the wake of the challenger, and, besides, I had done that sort of thing before with Joe Frazier. So I begged off. I said I didn’t have any equipment to run in.

We came in very late from the gambling casinos in Kinshasa—around three in the morning—and Mailer was just coming through the lobby on his way out to his car. He had sneakers on, and long athletic socks rolled up over the legs of what was probably a track suit but of a woolly texture that made it look more like a union suit, so that as he came through the lobby Norman gave the appearance of a hotel guest forced to evacuate his room in his underwear because of fire: the impression was heightened by the fact that he was carrying a toilet kit.

That night he and I had dinner and he told me what had happened. He had kept up with Ali for a couple of miles into the country upriver from the compound at N’Sele, but then he had begun to tire, and finally he stopped, his chest heaving, and he watched Ali disappear into the night with his sparring partners. In the east, over the hills, the African night was beginning to give way to the first streaks of dawn, but it was still very dark. Suddenly, and seemingly so close that it made him start, came the reverberating roar of a lion, an unmistakable coughing, grunting sound that seemed to come from all sides—just as one had read it did in Hemingway or Ruark—and Norman turned and set out for the distant lights of N’Sele at a hasty clip. He told me he had been instantly provided with a substantial “second wind” and he found himself moving along much quicker than during his outbound trip. He reached N’Sele safely, jogging by the dark compounds, exhilarated not only by his escape but by the irresistible thought of how highly dramatic it would have been if he hadn’t made it.

I asked him what he was talking about, and he grinned shyly and began to admit that once he had got to the sanctuary of the compound he had been quite taken by the fancy of being finished off right there by the lion…all in all not a bad way to go, certainly a dramatic death right up there with the more memorable of the litterateurs’—Saint-Exupéry’s or Shelley’s or Rupert Brooke’s—and the thought crossed his mind what an enviable last line for the biographical notes in the big dun-colored high-school anthologies: that Norman Mailer had been killed by an African lion near the banks of the Zaire in his fifty-first year.

Well, his fancy had all come to dross, he went on, because Muhammad Ali had returned from his run, his villa crowded with his people, and Norman had not been able to resist revealing the incident of the lion. It was greeted first with silence, everybody looking at him, and then the laughter started, first giggles, then hard thigh-slapping whoops, because they had all heard the lion, too, and heard him just about every morning, because that lion was behind bars in the presidential compound, a zoo lion—there weren’t any lions in the wild in West Africa anyway—and the thought of Mailer’s eyes staring into the darkness, and his legs pumping in his union-suit track clothes to get himself out of there (“Feets, do your stuff”) was so rich that Ali’s friend Bundini finally asked him to tell them about it all over again. “Nawmin, tell us ‘bout the big lion!”

It was interesting listening to Mailer talk about this—quite shyly and not without self-mockery, and yet with a curious wistfulness. He told me that the other fancy of this sort which he could remember involved a whale he had seen swimming through a regatta off Provincetown, Massachusetts—very impressive sight—and he thought that would not be a bad obituary note either: “Taken by a whale off Cape Cod in his fifty-first year.” Hemingway? Melville? He couldn’t make up his mind.

Later that evening, in the bar at the Inter-Continental, I found myself talking to an Englishwoman who described herself as a “free-lance poet.” She was hitchhiking her way up the west coast of Africa. I thought of her standing in a dusty African road in the darkness of the early dawn, and I mentioned Mailer’s fantasy. “Consumed by a lion? What on earth for?” she asked. Her eyes widened, as if she had suddenly seen an image, and she said that she thought—if one had to “shuffle off”—it would be terrific to be electrocuted while playing a bass guitar in a rock group.

“Oh, yes,” I said.

“I think it happens quite often,” she told me. She had an idea that rock groups which flickered into vague prominence, with a hit record perhaps, and were not heard of again were actually victims of electrocution. “In Alabama in the summer, that’s when it happens,” she said. “In an open-air concert in a meadow outside of town where they’ve built a big stage of pine, and the quick summer storms come through, or the local electricians aren’t the best, and all of a sudden zip!—the top guitarist of the Four Nuts, or the Wild Hens, or whatever, glows briefly up there on the stage, his hair standing up like an old-fashioned shaving brush, and he’s gone.”

We came in very late from the gambling casinos in Kinshasa—around three in the morning—and Mailer was just coming through the lobby on his way out to his car. He had sneakers on, and long athletic socks rolled up over the legs of what was probably a track suit but of a woolly texture that made it look more like a union suit, so that as he came through the lobby Norman gave the appearance of a hotel guest forced to evacuate his room in his underwear because of fire: the impression was heightened by the fact that he was carrying a toilet kit.

That night he and I had dinner and he told me what had happened. He had kept up with Ali for a couple of miles into the country upriver from the compound at N’Sele, but then he had begun to tire, and finally he stopped, his chest heaving, and he watched Ali disappear into the night with his sparring partners. In the east, over the hills, the African night was beginning to give way to the first streaks of dawn, but it was still very dark. Suddenly, and seemingly so close that it made him start, came the reverberating roar of a lion, an unmistakable coughing, grunting sound that seemed to come from all sides—just as one had read it did in Hemingway or Ruark—and Norman turned and set out for the distant lights of N’Sele at a hasty clip. He told me he had been instantly provided with a substantial “second wind” and he found himself moving along much quicker than during his outbound trip. He reached N’Sele safely, jogging by the dark compounds, exhilarated not only by his escape but by the irresistible thought of how highly dramatic it would have been if he hadn’t made it.

I asked him what he was talking about, and he grinned shyly and began to admit that once he had got to the sanctuary of the compound he had been quite taken by the fancy of being finished off right there by the lion…all in all not a bad way to go, certainly a dramatic death right up there with the more memorable of the litterateurs’—Saint-Exupéry’s or Shelley’s or Rupert Brooke’s—and the thought crossed his mind what an enviable last line for the biographical notes in the big dun-colored high-school anthologies: that Norman Mailer had been killed by an African lion near the banks of the Zaire in his fifty-first year.

Well, his fancy had all come to dross, he went on, because Muhammad Ali had returned from his run, his villa crowded with his people, and Norman had not been able to resist revealing the incident of the lion. It was greeted first with silence, everybody looking at him, and then the laughter started, first giggles, then hard thigh-slapping whoops, because they had all heard the lion, too, and heard him just about every morning, because that lion was behind bars in the presidential compound, a zoo lion—there weren’t any lions in the wild in West Africa anyway—and the thought of Mailer’s eyes staring into the darkness, and his legs pumping in his union-suit track clothes to get himself out of there (“Feets, do your stuff”) was so rich that Ali’s friend Bundini finally asked him to tell them about it all over again. “Nawmin, tell us ‘bout the big lion!”

It was interesting listening to Mailer talk about this—quite shyly and not without self-mockery, and yet with a curious wistfulness. He told me that the other fancy of this sort which he could remember involved a whale he had seen swimming through a regatta off Provincetown, Massachusetts—very impressive sight—and he thought that would not be a bad obituary note either: “Taken by a whale off Cape Cod in his fifty-first year.” Hemingway? Melville? He couldn’t make up his mind.

Later that evening, in the bar at the Inter-Continental, I found myself talking to an Englishwoman who described herself as a “free-lance poet.” She was hitchhiking her way up the west coast of Africa. I thought of her standing in a dusty African road in the darkness of the early dawn, and I mentioned Mailer’s fantasy. “Consumed by a lion? What on earth for?” she asked. Her eyes widened, as if she had suddenly seen an image, and she said that she thought—if one had to “shuffle off”—it would be terrific to be electrocuted while playing a bass guitar in a rock group.

“Oh, yes,” I said.

“I think it happens quite often,” she told me. She had an idea that rock groups which flickered into vague prominence, with a hit record perhaps, and were not heard of again were actually victims of electrocution. “In Alabama in the summer, that’s when it happens,” she said. “In an open-air concert in a meadow outside of town where they’ve built a big stage of pine, and the quick summer storms come through, or the local electricians aren’t the best, and all of a sudden zip!—the top guitarist of the Four Nuts, or the Wild Hens, or whatever, glows briefly up there on the stage, his hair standing up like an old-fashioned shaving brush, and he’s gone.”

Frito Pie

Most likely the idea for this happy union of chuck-wagon grub and Mexican street food occurred independently to a number of folks. Since then it’s been fancified (duck chili and goat cheese), bastardized (witness the “apple hash and pumpkin gravy Fritos pie” at fritospieremix.com), and improvised (let us hail the 7-Eleven Frito pie, in which an expeditious meal is made with a pocketknife and a furtive run on the hot dog condiments). But like the Frito itself, there’s no better version than the classic.

Serves 1

1 two-ounce bag of original Fritos

Pot of chili, homemade or canned

(I am loath to endorse any sort of canned meat product, but Texans swear by Wolf Brand.)

Grated cheddar cheese

Diced white onion

Take a knife or some scissors and split the bag down the front.

Ladle in a scoop of chili.

Top with a mound of cheese and a heap of onion.

Festoon your creation to your heart’s content (sour cream, jalapeños, avocado, and so on), though expect to be chastised by purists.

Eat it straight out of the bag, preferably atop a thick pile of paper napkins.

by Courtney Bond, Texas Monthly | Read more:

Image: Jody HortonMonday, September 23, 2013

Chaos Computer Club breaks Apple TouchID

[ed. See also: Biometric Technology Takes Off]

The biometrics hacking team of the Chaos Computer Club (CCC) has successfully bypassed the biometric security of Apple's TouchID using easy everyday means. A fingerprint of the phone user, photographed from a glass surface, was enough to create a fake finger that could unlock an iPhone 5s secured with TouchID. This demonstrates – again – that fingerprint biometrics is unsuitable as [an] access control method and should be avoided.

Apple had released the new iPhone with a fingerprint sensor that was supposedly much more secure than previous fingerprint technology. A lot of bogus speculation about the marvels of the new technology and how hard to defeat it supposedly is had dominated the international technology press for days.

Apple had released the new iPhone with a fingerprint sensor that was supposedly much more secure than previous fingerprint technology. A lot of bogus speculation about the marvels of the new technology and how hard to defeat it supposedly is had dominated the international technology press for days.

"In reality, Apple's sensor has just a higher resolution compared to the sensors so far. So we only needed to ramp up the resolution of our fake", said the hacker with the nickname Starbug, who performed the critical experiments that led to the successful circumvention of the fingerprint locking. "As we have said now for more than years, fingerprints should not be used to secure anything. You leave them everywhere, and it is far too easy to make fake fingers out of lifted prints." [1]

The iPhone TouchID defeat has been documented in a short video.

The method follows the steps outlined in this how-to with materials that can be found in almost every household: First, the fingerprint of the enroled user is photographed with 2400 dpi resolution. The resulting image is then cleaned up, inverted and laser printed with 1200 dpi onto transparent sheet with a thick toner setting. Finally, pink latex milk or white woodglue is smeared into the pattern created by the toner onto the transparent sheet. After it cures, the thin latex sheet is lifted from the sheet, breathed on to make it a tiny bit moist and then placed onto the sensor to unlock the phone. This process has been used with minor refinements and variations against the vast majority of fingerprint sensors on the market.

"We hope that this finally puts to rest the illusions people have about fingerprint biometrics. It is plain stupid to use something that you can´t change and that you leave everywhere every day as a security token", said Frank Rieger, spokesperson of the CCC. "The public should no longer be fooled by the biometrics industry with false security claims. Biometrics is fundamentally a technology designed for oppression and control, not for securing everyday device access." Fingerprint biometrics in passports has been introduced in many countries despite the fact that by this global roll-out no security gain can be shown.

by frank, CCC | Read more:

The biometrics hacking team of the Chaos Computer Club (CCC) has successfully bypassed the biometric security of Apple's TouchID using easy everyday means. A fingerprint of the phone user, photographed from a glass surface, was enough to create a fake finger that could unlock an iPhone 5s secured with TouchID. This demonstrates – again – that fingerprint biometrics is unsuitable as [an] access control method and should be avoided.

Apple had released the new iPhone with a fingerprint sensor that was supposedly much more secure than previous fingerprint technology. A lot of bogus speculation about the marvels of the new technology and how hard to defeat it supposedly is had dominated the international technology press for days.

Apple had released the new iPhone with a fingerprint sensor that was supposedly much more secure than previous fingerprint technology. A lot of bogus speculation about the marvels of the new technology and how hard to defeat it supposedly is had dominated the international technology press for days."In reality, Apple's sensor has just a higher resolution compared to the sensors so far. So we only needed to ramp up the resolution of our fake", said the hacker with the nickname Starbug, who performed the critical experiments that led to the successful circumvention of the fingerprint locking. "As we have said now for more than years, fingerprints should not be used to secure anything. You leave them everywhere, and it is far too easy to make fake fingers out of lifted prints." [1]

The iPhone TouchID defeat has been documented in a short video.

The method follows the steps outlined in this how-to with materials that can be found in almost every household: First, the fingerprint of the enroled user is photographed with 2400 dpi resolution. The resulting image is then cleaned up, inverted and laser printed with 1200 dpi onto transparent sheet with a thick toner setting. Finally, pink latex milk or white woodglue is smeared into the pattern created by the toner onto the transparent sheet. After it cures, the thin latex sheet is lifted from the sheet, breathed on to make it a tiny bit moist and then placed onto the sensor to unlock the phone. This process has been used with minor refinements and variations against the vast majority of fingerprint sensors on the market.

"We hope that this finally puts to rest the illusions people have about fingerprint biometrics. It is plain stupid to use something that you can´t change and that you leave everywhere every day as a security token", said Frank Rieger, spokesperson of the CCC. "The public should no longer be fooled by the biometrics industry with false security claims. Biometrics is fundamentally a technology designed for oppression and control, not for securing everyday device access." Fingerprint biometrics in passports has been introduced in many countries despite the fact that by this global roll-out no security gain can be shown.

by frank, CCC | Read more:

Image via:

Boys 'Round Here

I was something to see on the May morning I left Missoula, Montana, for good, all my earthly belongings jammed in the back seat of my ’95 Oldsmobile Cutlass Ciera, which is heavily dented and extremely pink. Missoula is a wacky and lovable university town that is home to a half-dozen microbreweries, herds of urban deer, and one saloon that has been open continuously, 24 hours a day, since 1883. I lived there for four happy and shiftless years of reading, waitressing, whiskey, inner tubing, burritos, and karaoke. I lit out on Interstate 90 for my parents’ house in Lincoln, Nebraska, washed in the wide-open sadness of the American range.

The indulgent, corny romance of my melancholy was not lost on me. I saw myself as straight out of a country song. I left Missoula early on a Sunday. Milk crates of clothes and books in my back seat. Cruising I-90 in my pink Oldsmobile. Something something something steering wheel.

The indulgent, corny romance of my melancholy was not lost on me. I saw myself as straight out of a country song. I left Missoula early on a Sunday. Milk crates of clothes and books in my back seat. Cruising I-90 in my pink Oldsmobile. Something something something steering wheel.

The maudlin country-western spirit of my situation was what motivated my experiment: for all of my 18-hour drive through some of the emptiest parts of the American West, I would listen to country radio. I cultivated an interest in contemporary country music similar to my enthusiasm for any other pop culture that is craven, crappy, backward, prepackaged, and shallow. Entertainment that is lucrative and ubiquitous, loved by many and known by most, can tell us a lot about our emotional triggers — and I don’t say that in a removed, condescending way. I am not an anthropological researcher of my own culture. Commercial pop culture is engineered to make people respond to it, and I respond to it. And the common tropes in country music broadcast the genre’s values so astoundingly literally that the feelings, beliefs, and history it appeals to in its audience are more obvious than for any other kind of American music.

I anticipated that my country radio marathon would be novel, enjoyable, and occasionally grating. What I did not account for was the concurrence of my trip and Memorial Day weekend, and all the cringing that would accompany hours of patriotic bathos. “Support our troops/America fuck yeah” is a venerable trope of commercial country music — driving through southern Wyoming I heard Johnny Cash’s “Ragged Old Flag,” a Vietnam-era spoken number expressing contempt for anyone who doesn’t smile with favor on all of the USA’s contemporary and historical military entanglements. Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA,” which updated displays of American patriotism to the Reagan years’ sappy jingoism, has become something of a standard.

Of course, today’s leading country saber-rattler is Toby Keith, whose anthem “American Soldier” — with lyrics as lazy you’d expect: “Oh and I don’t want to die for you/But if dying’s asked of me/I’ll bear that cross with honor/’Cause freedom don’t come free” — I heard just west of Scottsbluff, Nebraska. Keith took up his role as country’s patriotism police during his famous feud with the Dixie Chicks in 2003, after their lead singer Natalie Maines made statements criticizing President George Bush and the Iraq War.

At a concert, Keith displayed a picture of Maines photoshopped with a picture of Saddam Hussein, and Maines struck back by wearing a shirt saying “F.U.T.K.” to perform at the Academy of Country Music Awards. But Keith was vindicated — he won Album of the Year at the Awards for his über-patriotic Shock’n Y’all, while the Dixie Chicks were largely banished from country radio for their political statements. The Keith-Dixie Chicks conflict can illuminate a lot about country music’s gender dynamics. The genre’s most successful female act spoke out against authority, and the genre’s most successful male act felt it was his place to punish them for it. This is a notable pattern: in contemporary country, women are rebellious and angry, subverting a stifling (read: conservative small town) societal order whenever possible, while men hold fast to traditional norms, at turns smug and defiant.

This is pretty much the entire reason I almost always respond favorably to female artists on country radio, and to male artists almost never. The female singers are also more appealing vocalists, since a majority of male artists sing in corny, croony, tuneless baritone voices, imitating Keith and Garth Brooks. My most recent country favorite is Kacey Musgraves, who has taken up the space Taylor Swift vacated when she all but abandoned country for the greener pastures of pop radio. Like Swift, Musgraves is a young woman who sings in a simple, unaffected alto and writes most of her own music. But Musgraves is like Swift’s brunette alter ego in her “You Belong With Me” video — she is Swift with a dark side, singing, on her major-label debut album Same Trailer Different Park, about smoking pot and sleeping with her ex-boyfriends.

Musgraves has perfected an expression of the female country trope of longing to leave a dead-end hometown. Her single “Blowin' Smoke” describes a group of waitresses and their big talk about quitting smoking and quitting their jobs. Her first hit, “Merry Go ‘Round,” is a sharp and sad panorama of small-town life, where “Mama’s hooked on Mary Kay/Brother's hooked on Mary Jane/Daddy’s hooked on Mary two doors down.” Musgraves displays sardonic insight about why people in towns like these behave the way they do. “Same checks we’re always cashin’/To buy a little more distraction,” she sings, and, more to the point, “We’re so bored until we’re buried.”

The indulgent, corny romance of my melancholy was not lost on me. I saw myself as straight out of a country song. I left Missoula early on a Sunday. Milk crates of clothes and books in my back seat. Cruising I-90 in my pink Oldsmobile. Something something something steering wheel.

The indulgent, corny romance of my melancholy was not lost on me. I saw myself as straight out of a country song. I left Missoula early on a Sunday. Milk crates of clothes and books in my back seat. Cruising I-90 in my pink Oldsmobile. Something something something steering wheel.The maudlin country-western spirit of my situation was what motivated my experiment: for all of my 18-hour drive through some of the emptiest parts of the American West, I would listen to country radio. I cultivated an interest in contemporary country music similar to my enthusiasm for any other pop culture that is craven, crappy, backward, prepackaged, and shallow. Entertainment that is lucrative and ubiquitous, loved by many and known by most, can tell us a lot about our emotional triggers — and I don’t say that in a removed, condescending way. I am not an anthropological researcher of my own culture. Commercial pop culture is engineered to make people respond to it, and I respond to it. And the common tropes in country music broadcast the genre’s values so astoundingly literally that the feelings, beliefs, and history it appeals to in its audience are more obvious than for any other kind of American music.

I anticipated that my country radio marathon would be novel, enjoyable, and occasionally grating. What I did not account for was the concurrence of my trip and Memorial Day weekend, and all the cringing that would accompany hours of patriotic bathos. “Support our troops/America fuck yeah” is a venerable trope of commercial country music — driving through southern Wyoming I heard Johnny Cash’s “Ragged Old Flag,” a Vietnam-era spoken number expressing contempt for anyone who doesn’t smile with favor on all of the USA’s contemporary and historical military entanglements. Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA,” which updated displays of American patriotism to the Reagan years’ sappy jingoism, has become something of a standard.

Of course, today’s leading country saber-rattler is Toby Keith, whose anthem “American Soldier” — with lyrics as lazy you’d expect: “Oh and I don’t want to die for you/But if dying’s asked of me/I’ll bear that cross with honor/’Cause freedom don’t come free” — I heard just west of Scottsbluff, Nebraska. Keith took up his role as country’s patriotism police during his famous feud with the Dixie Chicks in 2003, after their lead singer Natalie Maines made statements criticizing President George Bush and the Iraq War.

At a concert, Keith displayed a picture of Maines photoshopped with a picture of Saddam Hussein, and Maines struck back by wearing a shirt saying “F.U.T.K.” to perform at the Academy of Country Music Awards. But Keith was vindicated — he won Album of the Year at the Awards for his über-patriotic Shock’n Y’all, while the Dixie Chicks were largely banished from country radio for their political statements. The Keith-Dixie Chicks conflict can illuminate a lot about country music’s gender dynamics. The genre’s most successful female act spoke out against authority, and the genre’s most successful male act felt it was his place to punish them for it. This is a notable pattern: in contemporary country, women are rebellious and angry, subverting a stifling (read: conservative small town) societal order whenever possible, while men hold fast to traditional norms, at turns smug and defiant.

This is pretty much the entire reason I almost always respond favorably to female artists on country radio, and to male artists almost never. The female singers are also more appealing vocalists, since a majority of male artists sing in corny, croony, tuneless baritone voices, imitating Keith and Garth Brooks. My most recent country favorite is Kacey Musgraves, who has taken up the space Taylor Swift vacated when she all but abandoned country for the greener pastures of pop radio. Like Swift, Musgraves is a young woman who sings in a simple, unaffected alto and writes most of her own music. But Musgraves is like Swift’s brunette alter ego in her “You Belong With Me” video — she is Swift with a dark side, singing, on her major-label debut album Same Trailer Different Park, about smoking pot and sleeping with her ex-boyfriends.

Musgraves has perfected an expression of the female country trope of longing to leave a dead-end hometown. Her single “Blowin' Smoke” describes a group of waitresses and their big talk about quitting smoking and quitting their jobs. Her first hit, “Merry Go ‘Round,” is a sharp and sad panorama of small-town life, where “Mama’s hooked on Mary Kay/Brother's hooked on Mary Jane/Daddy’s hooked on Mary two doors down.” Musgraves displays sardonic insight about why people in towns like these behave the way they do. “Same checks we’re always cashin’/To buy a little more distraction,” she sings, and, more to the point, “We’re so bored until we’re buried.”

by Alice Bolin, LA Review of Books | Read more:

Image: uncredited

Dinner Is Printed

The hype over 3-D printing intensifies by the day. Will it save the world? Will it bring on the apocalypse, with millions manufacturing their own AK-47s? Or is it all an absurd hubbub about a machine that spits out chintzy plastic trinkets? I decided to investigate. My plan: I would immerse myself in the world of 3-D printing. I would live for a week using nothing but 3-D-printed objects — toothbrushes, furniture, bicycles, vitamin pills — in order to judge the technology’s potential and pitfalls.

I approached Hod Lipson, a Cornell engineering professor and one of the nation’s top 3-D printing experts, with my idea. He thought it sounded like a great project. It would cost me a mere $50,000 or so.

I approached Hod Lipson, a Cornell engineering professor and one of the nation’s top 3-D printing experts, with my idea. He thought it sounded like a great project. It would cost me a mere $50,000 or so.Unless I was going to 3-D print counterfeit Fabergé eggs for the black market, I’d need a Plan B.

Which is how I settled on the idea of creating a 3-D-printed meal. I’d make 3-D-printed plates, forks, place mats, napkin rings, candlesticks — and, of course, 3-D-printed food. Yes, cuisine can be 3-D printed, too. And, in fact, Mr. Lipson thinks food might be this technology’s killer app. (More on that later.)

I wanted to serve the meal to my wife as the ultimate high-tech romantic dinner date. A friend suggested that, to finish the evening off, we hire a Manhattan-based company that scans and makes 3-D replicas of your private parts. That’s where I drew the line.

As it turned out, the dinner was perhaps the most labor-intensive meal in history. But it did give me a taste of the future, in both its utopian and dystopian aspects.

by A.J. Jacobs, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Tony CenicolaThe Fed Has Investors Overjoyed For All the Wrong Reasons

[ed. See also: Is the Fed an Enabler?]

[ed. See also: Is the Fed an Enabler?]I suspect that I will always remember where I was when the Federal Reserve stunned markets on Wednesday by deciding not taper its experimental support for markets and the economy — just like I suspect that I will always remember where I was on May 22nd when the Fed surprised many by indicating that a taper was likely to be forthcoming. In-between, markets have gone on a wild roller coaster roundtrip that also speaks to what continues to be a disappointingly tentative economic recovery and frustratingly weak job creation.

All this is quite perplexing given that the Fed is not in the business of surprising markets, and understandably so. Surprises tend to increase uncertainty premiums which then can act as a tax on financial intermediation and economic activity. They can also undermine the credibility of an institution that is central to the wellbeing of the nation.

If anything, the Fed under Ben Bernanke has made a point of enhancing “transparency.” Mr. Bernanke is the most communicative chairman in Fed history. He and his colleagues are releasing more data and projections than ever before. And Janet Yellen, the Fed’s vice governor and Mr. Bernanke’s likely successor, has led a comprehensive transparency initiative.

Yet the Fed has ended up surprising in major ways over the last few months, leading to wild gyrations in markets. The Dow collapsed by 5% between May 21st and June 24th, before surging by 8% to a new record close on Wednesday. Commodity and bond markets have also been quite volatile, with the benchmark 10-year Treasury unusually trading in an almost 50 basis point range.

Changes in underlying economic fundamentals do not warrant such volatility. While the economy continues to heal, it is has remained stuck in a multiyear, low-level growth equilibrium that frustrates job creation and worsens income distribution.

It could be that the Fed is really worried about the upcoming congressional battles over funding the government and lifting the debt ceiling. As illustrated by the debacle of the summer of 2011, a slippage could undermine economic performance. And we should never underestimate the appetite of our polarized Congress for self-manufactured challenges. Having said this, the Fed usually prefers to be reactive rather than proactive in such situations.

It is also hard to argue that the Fed has made a major discovery about the longer-term impact of what is after all a highly experimental policy approach. If anything, our central bankers (and, I would argue, everybody else) are essentially in the dark when it comes to the specific evolution over time of what Mr. Bernanke labeled back in 2010 the “benefits, costs and risks” of prolonged reliance on unconventional monetary policy.

We have to go elsewhere to explain the Fed’s unusual surprises. And my preferred explanation at this point — based on partial information and a gut feel — has to do with decision making under considerable uncertainty and changing leadership.

When faced with a challenging decision, we all love focusing on what can go right. It is our natural comfort zone. Yet, particularly in circumstances of extreme uncertainty, it is also important to assess the potential scale and scope of what can go wrong.

by Mohamed A. El-Erian, The Atlantic | Read more:

Image: Reuters

Out of Season

But Russell had wanted to leave New York for years, and he was stubborn. He missed fresh air and open space, so much so that after we had been together for about a year and a half he issued what was essentially an ultimatum: I’m going, with or without you, preferably with you, but I’m going. It meant giving up everything I had worked so hard for, the toehold I had carved out in my career, the identity I had assembled, and everyone else I loved, so of course I said yes.

I said “yes” to moving but I hadn’t really said “yes” to a location. Because Russell was an urban planner, with experience that was in high demand, he could work almost anywhere. He had been a Peace Corps volunteer and was interested in living abroad again — somewhere English-speaking, he conceded, so I could get a job. He wanted to be close to places to canoe and hike and climb. He wanted to live in a smaller city. Wherever we ended up, it was understood that we would stay there for a year or two before settling down back home in the Midwest. In theory I was on board with all of this, and as he started to look for jobs and then started getting offers, I remained theoretically fine with all of the potential locations; I was in over my head at my own job and barely had time to get coffee in the morning, let alone ruminate on the implications of these very important decisions.

When Russell asked, almost in passing, how about New Zealand? I thought about Lord of the Rings for a second and told him to apply for the job. I really did not think he would get it, and if he did, there was no way he would say yes — it was so far! And all of this was far less real than the onslaught of demanding emails and sensitive situations I dealt with every day at work and the numb comfort of sinking into bed next to him at the end of a hellishly long day. In the end, one offer was from Calgary, another from San Francisco, and there was probably a third that I can’t even remember now. But he accepted the one from the city council in Christchurch, New Zealand, and moved there in the summer of 2005.

I had only been at my terrifying yet oddly fulfilling job for a few months, and I wanted to stick it out for at least a year, so we agreed to do long distance for an unspecified amount of time. “Long” distance was so accurate it was funny, almost. Depending on the season, the time difference was between 14 and 16 hours, which meant that to talk on the phone one of us had to either get up before 6 a.m. or stay awake past midnight, and this was pre-Skype/Gchat, so we were both spending a small fortune on phone cards. He wrote me a lot of letters, and when I find them now, they still make me cry. He was so happy, and I, in retrospect, distracted and confused and utterly unsure of what I actually wanted.

After eight months of this, he returned to the U.S. to visit me and his family. Bad weather and travel delays cut “my” part short, and I remember riding the subway back to my apartment after saying goodbye to him at the airport, crying in an orange seat in the corner and thinking I could not do this another time, that any amount of career stagnation or uncertainty or opportunity loss was worth not having to say goodbye another time. That’s when I started making plans in earnest, started shopping for tickets, giving away my things, began to acknowledge I was really going to leave. Four months later, in June of 2006, I left.

by Ruth Curry, Buzzfeed | Read more:

Image: Justine Zwiebel / BuzzFeedSunday, September 22, 2013

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)