Friday, December 20, 2013

A New — and Reversible — Cause of Aging

Researchers have discovered a cause of aging in mammals that may be reversible: a series of molecular events that enable communication inside cells between the nucleus and mitochondria.

As communication breaks down, aging accelerates. By administering a molecule naturally produced by the human body, scientists restored the communication network in older mice. Subsequent tissue samples showed key biological hallmarks that were comparable to those of much younger animals.

As communication breaks down, aging accelerates. By administering a molecule naturally produced by the human body, scientists restored the communication network in older mice. Subsequent tissue samples showed key biological hallmarks that were comparable to those of much younger animals.

“The aging process we discovered is like a married couple — when they are young, they communicate well, but over time, living in close quarters for many years, communication breaks down,” said Harvard Medical School Professor of Genetics David Sinclair, senior author on the study. “And just like with a couple, restoring communication solved the problem.” (...)

As Gomes and her colleagues investigated potential causes for this, they discovered an intricate cascade of events that begins with a chemical called NAD and concludes with a key molecule that shuttles information and coordinates activities between the cell’s nuclear genome and the mitochondrial genome. Cells stay healthy as long as coordination between the genomes remains fluid. SIRT1’s role is intermediary, akin to a security guard; it assures that a meddlesome molecule called HIF-1 does not interfere with communication. (...)

Examining muscle from two-year-old mice that had been given the NAD-producing compound for just one week, the researchers looked for indicators of insulin resistance, inflammation, and muscle wasting. In all three instances, tissue from the mice resembled that of six-month-old mice. In human years, this would be like a 60-year-old converting to a 20-year-old in these specific areas.

One particularly important aspect of this finding involves HIF-1. More than just an intrusive molecule that foils communication, HIF-1 normally switches on when the body is deprived of oxygen. Otherwise, it remains silent. Cancer, however, is known to activate and hijack HIF-1. Researchers have been investigating the precise role HIF-1 plays in cancer growth.

“It’s certainly significant to find that a molecule that switches on in many cancers also switches on during aging,” said Gomes. “We’re starting to see now that the physiology of cancer is in certain ways similar to the physiology of aging. Perhaps this can explain why the greatest risk of cancer is age.”

As communication breaks down, aging accelerates. By administering a molecule naturally produced by the human body, scientists restored the communication network in older mice. Subsequent tissue samples showed key biological hallmarks that were comparable to those of much younger animals.

As communication breaks down, aging accelerates. By administering a molecule naturally produced by the human body, scientists restored the communication network in older mice. Subsequent tissue samples showed key biological hallmarks that were comparable to those of much younger animals.“The aging process we discovered is like a married couple — when they are young, they communicate well, but over time, living in close quarters for many years, communication breaks down,” said Harvard Medical School Professor of Genetics David Sinclair, senior author on the study. “And just like with a couple, restoring communication solved the problem.” (...)

As Gomes and her colleagues investigated potential causes for this, they discovered an intricate cascade of events that begins with a chemical called NAD and concludes with a key molecule that shuttles information and coordinates activities between the cell’s nuclear genome and the mitochondrial genome. Cells stay healthy as long as coordination between the genomes remains fluid. SIRT1’s role is intermediary, akin to a security guard; it assures that a meddlesome molecule called HIF-1 does not interfere with communication. (...)

Examining muscle from two-year-old mice that had been given the NAD-producing compound for just one week, the researchers looked for indicators of insulin resistance, inflammation, and muscle wasting. In all three instances, tissue from the mice resembled that of six-month-old mice. In human years, this would be like a 60-year-old converting to a 20-year-old in these specific areas.

One particularly important aspect of this finding involves HIF-1. More than just an intrusive molecule that foils communication, HIF-1 normally switches on when the body is deprived of oxygen. Otherwise, it remains silent. Cancer, however, is known to activate and hijack HIF-1. Researchers have been investigating the precise role HIF-1 plays in cancer growth.

“It’s certainly significant to find that a molecule that switches on in many cancers also switches on during aging,” said Gomes. “We’re starting to see now that the physiology of cancer is in certain ways similar to the physiology of aging. Perhaps this can explain why the greatest risk of cancer is age.”

by Ana P. Gomes, Kurzweil | Read more:

Image: Ana GomesEBay’s Strategy for Taking On Amazon

There has been much talk about Amazon driving retailers out of business — most recently, and somewhat unbelievably, by proposing to use drones to deliver purchases. For some time now, physical retailers have lived in fear of the various ways in which Amazon can undercut them. If you’re looking for a product that you don’t need to try on or try out, Amazon’s customer analytics and nationwide network of 40-plus enormous fulfillment centers is awfully tough to compete with. And even if you do need to try something on, Amazon conveniently includes a bar-code scanner in its mobile application so you can compare prices while you’re in a store and then have the same item shipped to your home with just a few clicks. (Retailers call this act of checking out products in a store and then buying them online from a different vendor ‘‘showrooming.’’) Amazon holds such sway that for many it’s the default place to buy things online.

And yet online commerce currently accounts for only about 6 percent of all commerce in the United States. We still buy more than 90 percent of everything we purchase offline, often by handing over money or swiping a credit card in exchange for the goods we want. But the proliferation of smartphones and tablets has increasingly led to the use of digital technology to help us make those purchases, and it’s in that convergence that eBay sees its opportunity. As Donahoe puts it: ‘‘We view it actually as and. Not online, not offline: Both.’’

And yet online commerce currently accounts for only about 6 percent of all commerce in the United States. We still buy more than 90 percent of everything we purchase offline, often by handing over money or swiping a credit card in exchange for the goods we want. But the proliferation of smartphones and tablets has increasingly led to the use of digital technology to help us make those purchases, and it’s in that convergence that eBay sees its opportunity. As Donahoe puts it: ‘‘We view it actually as and. Not online, not offline: Both.’’

Most people think of eBay as an online auction house, the world’s biggest garage sale, which it has been for most of its life. But since Donahoe took over in 2008, he has slowly moved the company beyond auctions, developing technology partnerships with big retailers like Home Depot, Macy’s, Toys ‘‘R’’ Us and Target and expanding eBay’s online marketplace to include reliable, returnable goods at fixed prices. (Auctions currently represent just 30 percent of the purchases made at eBay.com; the site sells 13,000 cars a week through its mobile app alone, many at fixed prices.)

Under Donahoe, eBay has made 34 acquisitions over the last five years, most of them to provide the company and its retail partners with enhanced technology. EBay can help with the back end of websites, create interactive storefronts in real-world locations, streamline the electronic-payment process or help monitor inventory in real time. (Outsourcing some of the digital strategy and technological operations to eBay frees up companies to focus on what they presumably do best: Make and market their own products.) In select cities, eBay has also recently introduced eBay Now, an app that allows you to order goods from participating local vendors and have them delivered to your door in about an hour for a $5 fee. The company is betting its future on the idea that its interactive technology can turn shopping into a kind of entertainment, or at least make commerce something more than simply working through price-plus-shipping calculations. If eBay can get enough people into Dick’s Sporting Goods to try out a new set of golf clubs and then get them to buy those clubs in the store, instead of from Amazon, there’s a business model there.

A key element of eBay’s vision of the future is the digital wallet. On a basic level, having a ‘‘digital wallet’’ means paying with your phone, but it’s about a lot more than that; it’s as much a concept as a product. EBay bought PayPal in 2002, after PayPal established itself as a safe way to transfer money between people who didn’t know each other (thus facilitating eBay purchases). For the last several years, eBay has regarded digital payments through mobile devices as having the potential to change everything — to become, as David Marcus, PayPal’s president, puts it, ‘‘Money 3.0.’’

And yet online commerce currently accounts for only about 6 percent of all commerce in the United States. We still buy more than 90 percent of everything we purchase offline, often by handing over money or swiping a credit card in exchange for the goods we want. But the proliferation of smartphones and tablets has increasingly led to the use of digital technology to help us make those purchases, and it’s in that convergence that eBay sees its opportunity. As Donahoe puts it: ‘‘We view it actually as and. Not online, not offline: Both.’’

And yet online commerce currently accounts for only about 6 percent of all commerce in the United States. We still buy more than 90 percent of everything we purchase offline, often by handing over money or swiping a credit card in exchange for the goods we want. But the proliferation of smartphones and tablets has increasingly led to the use of digital technology to help us make those purchases, and it’s in that convergence that eBay sees its opportunity. As Donahoe puts it: ‘‘We view it actually as and. Not online, not offline: Both.’’ Most people think of eBay as an online auction house, the world’s biggest garage sale, which it has been for most of its life. But since Donahoe took over in 2008, he has slowly moved the company beyond auctions, developing technology partnerships with big retailers like Home Depot, Macy’s, Toys ‘‘R’’ Us and Target and expanding eBay’s online marketplace to include reliable, returnable goods at fixed prices. (Auctions currently represent just 30 percent of the purchases made at eBay.com; the site sells 13,000 cars a week through its mobile app alone, many at fixed prices.)

Under Donahoe, eBay has made 34 acquisitions over the last five years, most of them to provide the company and its retail partners with enhanced technology. EBay can help with the back end of websites, create interactive storefronts in real-world locations, streamline the electronic-payment process or help monitor inventory in real time. (Outsourcing some of the digital strategy and technological operations to eBay frees up companies to focus on what they presumably do best: Make and market their own products.) In select cities, eBay has also recently introduced eBay Now, an app that allows you to order goods from participating local vendors and have them delivered to your door in about an hour for a $5 fee. The company is betting its future on the idea that its interactive technology can turn shopping into a kind of entertainment, or at least make commerce something more than simply working through price-plus-shipping calculations. If eBay can get enough people into Dick’s Sporting Goods to try out a new set of golf clubs and then get them to buy those clubs in the store, instead of from Amazon, there’s a business model there.

A key element of eBay’s vision of the future is the digital wallet. On a basic level, having a ‘‘digital wallet’’ means paying with your phone, but it’s about a lot more than that; it’s as much a concept as a product. EBay bought PayPal in 2002, after PayPal established itself as a safe way to transfer money between people who didn’t know each other (thus facilitating eBay purchases). For the last several years, eBay has regarded digital payments through mobile devices as having the potential to change everything — to become, as David Marcus, PayPal’s president, puts it, ‘‘Money 3.0.’’

by Jeff Himmelman, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Grant Cornett. Prop Stylist: Janine Iversen.The Chris McCandless Obsession Problem

Three years ago, Ackermann, 29, and her boyfriend, Etienne Gros, 27, tried to cross the Teklanika River, a couple of miles west from the Savage. They tied themselves to a rope that somebody had run from one bank to the other, to aid such attempts. The Teklanika is powerful in summertime, and about halfway across they lost their footing. The rope dipped into the water, and Ackermann and Gros, still tied on, were pulled under by its weight. Gros grabbed a knife, cut himself loose, and swam to shore. He waded back out to try and rescue Ackermann, but it was too late—she had already drowned. He cut her loose and swam with her body 300 yards downstream, where he dragged her to land on the river’s far shore. His attempts at CPR were useless.

Ackermann, who was from Switzerland, and Gros, a Frenchman, had been hiking the Stampede Trail, a route made famous by Christopher McCandless, who walked it in April 1992. Many people now know about McCandless and how the 24-year-old idealist bailed out of his middle-class suburban life, donated his $24,000 in savings to charity, and embarked on a two-year hitchhiking odyssey that led him to Alaska and the deserted Fairbanks City Transit bus number 142, which still sits, busted and rusting, 20 miles down the Stampede Trail. For 67 days, he ate mostly squirrel, ptarmigan, and porcupine, then he shaved his beard, packed his bag, and started walking back toward the highway. But a raging Teklanika prevented him from crossing, so he returned to the bus and hunkered down. More than a month later, a moose hunter found McCandless’s decomposed body in a sleeping bag inside the bus, where he had starved to death.

This tragic story was told by Jon Krakauer in the January 1993 issue of Outside and later in his bestselling 1997 book, Into the Wild. The book, anda 2007 film directed by Sean Penn, helped elevate the McCandless saga to the status of modern myth. And that, in turn, has given rise to a unique and curious phenomenon in Alaska: McCandless pilgrims, inspired by his story, who are determined to see the bus for themselves. Each year, scores of trekkers journey down the Stampede Trail to visit it. They camp at the bus for days, sometimes weeks, write essays in the various logbooks stowed inside, and ponder the impact that McCandless’s antimaterialist ethic, free-spirited travels, and time in the Alaskan wild has had on how they perceive the world.

Unfortunately, a lot of these people get into trouble, and almost always because of the Teklanika. (...)

Many Alaskans, of course, don’t feel any reverence for McCandless at all. The debate about his worth is often harsh; locals like to float theories about his death wish, his alleged schizophrenia, and his outright foolishness.

The intensity of the debate was rekindled this past September, when Jon Krakauer wrote a story for The New Yorker’s website that revised his theory about how McCandless died. Krakauer argued that it happened because of a neurotoxin called ODAP, which is found in a plant that McCandless was eating and can cause lathyrism, a condition that leads to paralysis. Because the plant is widely considered edible, Krakauer declared that this finding confirms his long-held belief that McCandless wasn’t “as clueless and incompetent as his detractors have made him out to be.”

Plenty of commentary ensued, and plenty of it charged with controversy. “Raised by a game guide in AK my family has ‘respect’ for the land that is different than city kids from ‘outside,’” wrote “kvalvik” in a comment on Krakauer’s article. “Respect for the land comes to mean it will kill you as fast as a slow rabbit in front of a fast fox.”

Few have been as scathingly critical of McCandless’s sympathizers as Craig Medred, an Alaskan who has written numerous pieces about him over the years. In the Alaska Dispatch this fall, Medred, responding to Krakauer’s article, noted the irony of “self-involved urban Americans, people more detached from nature than any society of humans in history, worshipping the noble, suicidal narcissist, the bum, thief and poacher Chris McCandless.”

The pilgrims often encounter similar disdain. I know of beer-toting locals on ATVs who falsely warned three hikers from Phoenix that a “forest fire” was burning between the Teklanika and the bus, urging them to turn back. A pair of hikers I met told me about their experience buying the film’s soundtrack at the Anchorage Barnes and Noble, where one man told them that the bus had been removed. When they went to the Backcountry Information Center at Denali National Park to ask questions about the hike, a ranger told them it wasn’t her job to tell them where the bus was, and that if they didn’t know, they had no business being out there. She said she would end up pulling their bodies out of the river.

Much of the polarization surrounding McCandless stems from a divide in people’s beliefs about what justifies risk-taking in the backcountry. In Alaska, it’s generally considered acceptable to invite risk while making a living on the land—fishing, hunting, logging, mushing, trapping. It is less acceptable to take chances in search of a more philosophical way of life.

by Diana Saverin, Outside | Read more:

Image: Diana Saverin

Seattle: Bertha Hits a Big Object

[ed. Problems, problems... not to mention a potential Ratpocalypse!]

A secret subterranean heart, tinged with mystery and myth, beats beneath the streets in many of the world’s great cities. Tourists seek out the catacombs of Rome, the sewers of Paris and the subway tunnels of New York. Some people believe a den of interstellar aliens lurks beneath Denver International Airport.

Now Seattle, at least for now, has joined that exclusive club.

Now Seattle, at least for now, has joined that exclusive club.

Something unknown, engineers say — and all the more intriguing to many residents for being unknown — has blocked the progress of the biggest-diameter tunnel-boring machine in use on the planet, a high-tech, largely automated wonder called Bertha. At five stories high with a crew of 20, the cigar-shaped behemoth was grinding away underground on a two-mile-long, $3.1 billion highway tunnel under the city’s waterfront on Dec. 6 when it encountered something in its path that managers still simply refer to as “the object.”

The object’s composition and provenance remain unknown almost two weeks after first contact because in a state-of-the-art tunneling machine, as it turns out, you can’t exactly poke your head out the window and look.

“What we’re focusing on now is creating conditions that will allow us to enter the chamber behind the cutter head and see what the situation is,” Chris Dixon, the project manager at Seattle Tunnel Partners, the construction contractor, said in an interview this week. Mr. Dixon said he felt pretty confident that the blockage will turn out to be nothing more or less romantic than a giant boulder, perhaps left over from the Ice Age glaciers that scoured and crushed this corner of the continent 17,000 years ago.

But the unknown is a tantalizing subject. Some residents said they believe, or want to believe, that a piece of old Seattle, buried in the pell-mell rush of city-building in the 1800s, when a mucky waterfront wetland was filled in to make room for commerce, could be Bertha’s big trouble. That theory is bolstered by the fact that the blocked tunnel section is also in the shallowest portion of the route, with the top of the machine only around 45 feet below street grade.

“I’m going to believe it’s a piece of Seattle history until proven otherwise,” said Ann Ferguson, the curator of the Seattle Collection at the Seattle Public Library, who said she held out hope for something of 1890s Klondike Gold Rush vintage, when Seattle became the crazed and booming gateway city to the gold fields of Alaska and Canada. (...)

The tunnel is to run north and south along Elliott Bay from Century Link Field, home of football’s Seahawks, to a point near the Space Needle on the north, allowing demolition of an elevated roadway and improved crosstown foot and bicycle access.

Economics and geology — two key threads of Seattle’s creation — underpin the tunnel’s impetus. Planning for the project began after an earthquake in 2001 revealed seismic vulnerability in the elevated viaduct roadway, which was built in the 1950s. Businesses and real estate interests were then sold on the idea that a tunnel, replacing the viaduct, would open access between downtown and the waterfront.

But unlike, say, Boston or New York, where tunnels are common and bedrock is close to the surface, getting to that end point is messy. Seattle’s underbelly is more like pudding than soil — a slurry of sand, gravel and clay, all jumbled and compressed by the pressures from a 3,000-foot-thick ice sheet that extended as far as Olympia, 50 miles south. A city famous for being wet also has a high water table, only about four to five feet down.

A secret subterranean heart, tinged with mystery and myth, beats beneath the streets in many of the world’s great cities. Tourists seek out the catacombs of Rome, the sewers of Paris and the subway tunnels of New York. Some people believe a den of interstellar aliens lurks beneath Denver International Airport.

Now Seattle, at least for now, has joined that exclusive club.

Now Seattle, at least for now, has joined that exclusive club.Something unknown, engineers say — and all the more intriguing to many residents for being unknown — has blocked the progress of the biggest-diameter tunnel-boring machine in use on the planet, a high-tech, largely automated wonder called Bertha. At five stories high with a crew of 20, the cigar-shaped behemoth was grinding away underground on a two-mile-long, $3.1 billion highway tunnel under the city’s waterfront on Dec. 6 when it encountered something in its path that managers still simply refer to as “the object.”

The object’s composition and provenance remain unknown almost two weeks after first contact because in a state-of-the-art tunneling machine, as it turns out, you can’t exactly poke your head out the window and look.

“What we’re focusing on now is creating conditions that will allow us to enter the chamber behind the cutter head and see what the situation is,” Chris Dixon, the project manager at Seattle Tunnel Partners, the construction contractor, said in an interview this week. Mr. Dixon said he felt pretty confident that the blockage will turn out to be nothing more or less romantic than a giant boulder, perhaps left over from the Ice Age glaciers that scoured and crushed this corner of the continent 17,000 years ago.

But the unknown is a tantalizing subject. Some residents said they believe, or want to believe, that a piece of old Seattle, buried in the pell-mell rush of city-building in the 1800s, when a mucky waterfront wetland was filled in to make room for commerce, could be Bertha’s big trouble. That theory is bolstered by the fact that the blocked tunnel section is also in the shallowest portion of the route, with the top of the machine only around 45 feet below street grade.

“I’m going to believe it’s a piece of Seattle history until proven otherwise,” said Ann Ferguson, the curator of the Seattle Collection at the Seattle Public Library, who said she held out hope for something of 1890s Klondike Gold Rush vintage, when Seattle became the crazed and booming gateway city to the gold fields of Alaska and Canada. (...)

The tunnel is to run north and south along Elliott Bay from Century Link Field, home of football’s Seahawks, to a point near the Space Needle on the north, allowing demolition of an elevated roadway and improved crosstown foot and bicycle access.

Economics and geology — two key threads of Seattle’s creation — underpin the tunnel’s impetus. Planning for the project began after an earthquake in 2001 revealed seismic vulnerability in the elevated viaduct roadway, which was built in the 1950s. Businesses and real estate interests were then sold on the idea that a tunnel, replacing the viaduct, would open access between downtown and the waterfront.

But unlike, say, Boston or New York, where tunnels are common and bedrock is close to the surface, getting to that end point is messy. Seattle’s underbelly is more like pudding than soil — a slurry of sand, gravel and clay, all jumbled and compressed by the pressures from a 3,000-foot-thick ice sheet that extended as far as Olympia, 50 miles south. A city famous for being wet also has a high water table, only about four to five feet down.

by Kirk Johnson, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Washington State Department of TransportationThursday, December 19, 2013

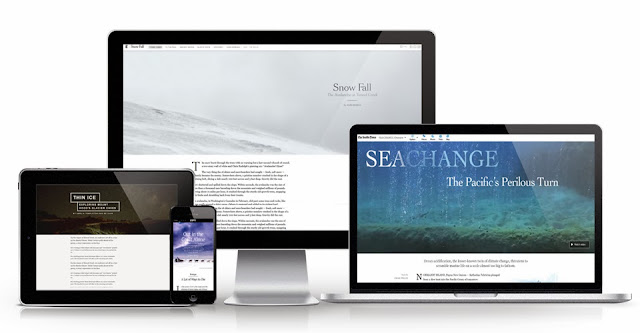

Inspiring Visual Storytelling

Opportunities abound for some creative thinking and here is a round up of some of the best examples of creative online storytelling to inspire you.

So what are the trends in some of the new storytelling projects?

by Heather Bryant, Alaska Media Lab | Read more:

Image: uncredited

R.I.P. The Blog, 1997-2013

Sometime in the past few years, the blog died. In 2014, people will finally notice. Sure, blogs still exist, many of them are excellent, and they will go on existing and being excellent for many years to come. But the function of the blog, the nebulous informational task we all agreed the blog was fulfilling for the past decade, is increasingly being handled by a growing number of disparate media forms that are blog-like but also decidedly not blogs.

Instead of blogging, people are posting to Tumblr, tweeting, pinning things to their board, posting to Reddit, Snapchatting, updating Facebook statuses, Instagramming, and publishing on Medium. In 1997, wired teens created online diaries, and in 2004 the blog was king. Today, teens are about as likely to start a blog (over Instagramming or Snapchatting) as they are to buy a music CD. Blogs are for 40-somethings with kids.I am not generally a bomb-thrower, but I wrote this piece in a deliberately provacative way. Blogs obviously aren’t dead and I acknowledged that much right from the title. I (obviously) think there’s a lot of value in the blog format, even apart from its massive influence on online media in general, but as someone who’s been doing it since 1998 and still does it every day, it’s difficult to ignore the blog’s diminished place in our informational diet. (...)

And yeah, what about Tumblr? Isn’t Tumblr full of blogs? Welllll, sort of. Back in 2005, tumblelogs felt like blogs but there was also something a bit different about them. Today they seem really different…I haven’t thought of Tumblrs as blogs for years…they’re Tumblrs! If you asked a typical 23-year-old Tumblr user what they called this thing they’re doing on the site, I bet “blogging” would not be the first (or second) answer. No one thinks of posting to their Facebook as blogging or tweeting as microblogging or Instagramming as photoblogging. And if the people doing it think it’s different, I’ll take them at their word. After all, when early bloggers were attempting to classify their efforts as something other online diaries or homepages, everyone eventually agreed…let’s not fight everyone else on their choice of subculture and vocabulary.

by Jason Kottke, Kottke.org | Read more:

Facebook Saves Everything

A couple of months ago, a friend of mine asked on Facebook:

A couple of months ago, a friend of mine asked on Facebook:"Do you think that Facebook tracks the stuff that people type and then erase before hitting <enter>? (or the 'post' button)"

Good question.

We spend a lot of time thinking about what to post on Facebook. Should you argue that political point your high school friend made? Do your friends really want to see yet another photo of your cat (or baby)? Most of us have, at one time or another, started writing something and then, probably wisely, changed our minds.

Advertisement

Unfortunately, the code that powers Facebook still knows what you typed – even if you decide not to publish it. It turns out the things you explicitly choose not to share aren't entirely private.

Facebook calls these unposted thoughts "self-censorship", and insights into how it collects these non-posts can be found in a recent paper written by two Facebookers. Sauvik Das, a PhD student at Carnegie Mellon and summer software engineer intern at Facebook, and Adam Kramer, a Facebook data scientist, have put online an article presenting their study of the self-censorship behaviour collected from 5 million English-speaking Facebook users. It reveals a lot about how Facebook monitors our unshared thoughts and what it thinks about them.

The study examined aborted status updates, posts on other people's timelines and comments on others' posts. To collect the text you type, Facebook sends code to your browser. That code automatically analyses what you type into any text box and reports metadata back to Facebook.

Storing text as you type isn't uncommon on other websites. For example, if you use Gmail, your draft messages are automatically saved as you type them. Even if you close the browser without saving, you can usually find a (nearly) complete copy of the email you were typing in your drafts folder. Facebook is using essentially the same technology here. The difference is that Google is saving your messages to help you. Facebook users don't expect their unposted thoughts to be collected, nor do they benefit from it.

It is not clear to the average reader how this data collection is covered by Facebook's privacy policy. In Facebook's Data Use Policy, under a section called "Information we receive and how it is used", it's made clear that the company collects information you choose to share or when you "view or otherwise interact with things". But nothing suggests that it collects content you explicitly don't share. Typing and deleting text in a box could be considered a type of interaction, but I suspect very few of us would expect that data to be saved. When I reached out to Facebook, a representative told me the company believes this self-censorship is a type of interaction covered by the policy.

by Jennifer Golbeck, Sydney Morning Herald | Read more:

Image: Slate

A Life of Noodles Comes Full Circle

At 50, Ivan Orkin appears to have pulled off a chain of unprecedented feats.

He is the first American brave (or foolish) enough to open his own ramen shop in Tokyo. (He now has two.)

He is the first chef to publish a cookbook/memoir, “Ivan Ramen,” in the United States before even opening a restaurant here.

And last week, he may have become the first chef in Manhattan to intercept a bathroom-bound customer and order her back to her seat.

And last week, he may have become the first chef in Manhattan to intercept a bathroom-bound customer and order her back to her seat.

“She got up right after the ramen hit the table!” he said in self-defense, citing the first commandment of ramen: It must be eaten while still volcanically hot.

With the opening of Ivan Ramen Slurp Shop in Hell’s Kitchen last month, Mr. Orkin became a New York restaurateur, a title 20 years in the making. A long stainless-steel counter in his restaurant is lined on one side with customers, and on the other with ramen ingredients: slow-cooked pork belly, scallions, soft-cooked eggs, chicken broth, dashi or seaweed broth, chicken fat, pork fat and his signature rye noodles.

He is having a hard time making peace with those noodles. “I can’t believe I’m not making my own,” he said ruefully. “That was the first thing I got right in Tokyo.” Instead, they are made for him at Sun Noodle in Teterboro, N.J., a supplier to preferred ramen destinations like Momofuku Noodle Bar, Ramen Yebisu and Ganso.

These restaurants are part of a greater New York ramen boom: Traditional purveyors like Ippudo and Totto Ramen are expanding, and mavericks like Mr. Orkin and Yuji Haraguchi of Yuji Ramen are reinventing the bowl. “We are very chef-driven,” said Kenshiro Uki, Sun Noodle’s East Coast manager. The company custom-makes more than 100 variations on ramen: thick and thin, flat and round, wavy and straight, white, yellow and even black, colored with charred bamboo leaf.

It is not hands-on enough for Mr. Orkin, but for now, he doesn’t have the time. His long-chaotic life as a chef has ordered itself around one dish, ramen, and he is racing to build the restaurants that will house his vision. That is not necessarily the most “authentic” ramen, but the ramen of his own Japanese-American-Jewish-chef dreams: a soup with the right balance of pork, chicken, smoked fish, soy and salt; noodles with the ideal combination of chew and give; toppings that set it off instead of overwhelming it. The recipe, as published in “Ivan Ramen,” is 36 pages long.

“I have officially become one of the ramen geeks,” he said.

In Tokyo (and in Japanophile clusters in the United States), ramen is much more than noodles in a rich, meaty broth. Like pizza and burgers in the United States, it has changed from fast food to a canvas of culinary ideas. “Kodawari” ramen is taken seriously and has the same buzzwords as “artisanal” here: free range, long cooked, slow raised, small batch. Ramen is not an ancient dish like sashimi or tofu. While there are vegetarian and seafood versions, the basic soup is rich with fat and meat — which was banned in Japan from approximately the seventh century to the 17th, according to Buddhist edicts.

But it has been popular for long enough to become a national obsession. Ramen otaku — geeks — compete on quiz shows, crowd-source maps and wait hours to try a place with a new twist: whole-grain noodles, for example, or especially thick slices of pork belly. Some ramen shops are famous for their garlicky broths; others for mind-blowing chile heat or intense sesame flavor; others for their strict policies of no talking or no perfume.

He is the first American brave (or foolish) enough to open his own ramen shop in Tokyo. (He now has two.)

He is the first chef to publish a cookbook/memoir, “Ivan Ramen,” in the United States before even opening a restaurant here.

And last week, he may have become the first chef in Manhattan to intercept a bathroom-bound customer and order her back to her seat.

And last week, he may have become the first chef in Manhattan to intercept a bathroom-bound customer and order her back to her seat.“She got up right after the ramen hit the table!” he said in self-defense, citing the first commandment of ramen: It must be eaten while still volcanically hot.

With the opening of Ivan Ramen Slurp Shop in Hell’s Kitchen last month, Mr. Orkin became a New York restaurateur, a title 20 years in the making. A long stainless-steel counter in his restaurant is lined on one side with customers, and on the other with ramen ingredients: slow-cooked pork belly, scallions, soft-cooked eggs, chicken broth, dashi or seaweed broth, chicken fat, pork fat and his signature rye noodles.

He is having a hard time making peace with those noodles. “I can’t believe I’m not making my own,” he said ruefully. “That was the first thing I got right in Tokyo.” Instead, they are made for him at Sun Noodle in Teterboro, N.J., a supplier to preferred ramen destinations like Momofuku Noodle Bar, Ramen Yebisu and Ganso.

These restaurants are part of a greater New York ramen boom: Traditional purveyors like Ippudo and Totto Ramen are expanding, and mavericks like Mr. Orkin and Yuji Haraguchi of Yuji Ramen are reinventing the bowl. “We are very chef-driven,” said Kenshiro Uki, Sun Noodle’s East Coast manager. The company custom-makes more than 100 variations on ramen: thick and thin, flat and round, wavy and straight, white, yellow and even black, colored with charred bamboo leaf.

It is not hands-on enough for Mr. Orkin, but for now, he doesn’t have the time. His long-chaotic life as a chef has ordered itself around one dish, ramen, and he is racing to build the restaurants that will house his vision. That is not necessarily the most “authentic” ramen, but the ramen of his own Japanese-American-Jewish-chef dreams: a soup with the right balance of pork, chicken, smoked fish, soy and salt; noodles with the ideal combination of chew and give; toppings that set it off instead of overwhelming it. The recipe, as published in “Ivan Ramen,” is 36 pages long.

“I have officially become one of the ramen geeks,” he said.

In Tokyo (and in Japanophile clusters in the United States), ramen is much more than noodles in a rich, meaty broth. Like pizza and burgers in the United States, it has changed from fast food to a canvas of culinary ideas. “Kodawari” ramen is taken seriously and has the same buzzwords as “artisanal” here: free range, long cooked, slow raised, small batch. Ramen is not an ancient dish like sashimi or tofu. While there are vegetarian and seafood versions, the basic soup is rich with fat and meat — which was banned in Japan from approximately the seventh century to the 17th, according to Buddhist edicts.

But it has been popular for long enough to become a national obsession. Ramen otaku — geeks — compete on quiz shows, crowd-source maps and wait hours to try a place with a new twist: whole-grain noodles, for example, or especially thick slices of pork belly. Some ramen shops are famous for their garlicky broths; others for mind-blowing chile heat or intense sesame flavor; others for their strict policies of no talking or no perfume.

by Julia Moskin, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Brent HerrigWednesday, December 18, 2013

Rumored Chase-Madoff Settlement Is Another Bad Joke

[ed. See also: The Financial Crisis: Why have no high-level executives been prosecuted?]

Just under two months ago, when the $13 billion settlement for JP Morgan Chase was coming down the chute, word leaked out that that the deal was no sure thing. Among other things, it was said that prosecutors investigating Chase's role in the Bernie Madoff caper – Chase was Madoff's banker – were insisting on a guilty plea to actual criminal charges, but that this was a deal-breaker for Chase.

Something had to give, and now, apparently, it has. Last week, it was reported that the state and Chase were preparing a separate $2 billion deal over the Madoff issues, a series of settlements that would also involve a deferred prosecution agreement.

Something had to give, and now, apparently, it has. Last week, it was reported that the state and Chase were preparing a separate $2 billion deal over the Madoff issues, a series of settlements that would also involve a deferred prosecution agreement.

The deferred-prosecution deal is a hair short of a guilty plea. The bank has to acknowledge the facts of the government's case and pay penalties, but as has become common in the Too-Big-To-Fail arena, we once again have a situation in which all sides will agree that a serious crime has taken place, but no individual has to pay for that crime.

As University of Michigan law professor David Uhlmann noted in a Times editorial at the end of last week, the use of these deferred prosecution agreements has exploded since the infamous Arthur Andersen case. In that affair, the company collapsed and 28,000 jobs were lost after Arthur Andersen was convicted on a criminal charge related to its role in the Enron scandal. As Uhlmann wrote:

Yes, you might very well lose some jobs if you go around indicting huge companies on criminal charges. You might even want to avoid doing so from time to time, if the company is worth saving.

But individuals? There's absolutely no reason why the state can't proceed against the actual people who are guilty of crimes.

Just under two months ago, when the $13 billion settlement for JP Morgan Chase was coming down the chute, word leaked out that that the deal was no sure thing. Among other things, it was said that prosecutors investigating Chase's role in the Bernie Madoff caper – Chase was Madoff's banker – were insisting on a guilty plea to actual criminal charges, but that this was a deal-breaker for Chase.

Something had to give, and now, apparently, it has. Last week, it was reported that the state and Chase were preparing a separate $2 billion deal over the Madoff issues, a series of settlements that would also involve a deferred prosecution agreement.

Something had to give, and now, apparently, it has. Last week, it was reported that the state and Chase were preparing a separate $2 billion deal over the Madoff issues, a series of settlements that would also involve a deferred prosecution agreement.The deferred-prosecution deal is a hair short of a guilty plea. The bank has to acknowledge the facts of the government's case and pay penalties, but as has become common in the Too-Big-To-Fail arena, we once again have a situation in which all sides will agree that a serious crime has taken place, but no individual has to pay for that crime.

As University of Michigan law professor David Uhlmann noted in a Times editorial at the end of last week, the use of these deferred prosecution agreements has exploded since the infamous Arthur Andersen case. In that affair, the company collapsed and 28,000 jobs were lost after Arthur Andersen was convicted on a criminal charge related to its role in the Enron scandal. As Uhlmann wrote:

From 2004 through 2012, the Justice Department entered into 242 deferred prosecution and nonprosecution agreements with corporations; there had been just 26 in the preceding 12 years.Since the AA mess, the state has been beyond hesitant to bring criminal charges against major employers for any reason. (The history of all of this is detailed in The Divide, a book I have coming out early next year.) The operating rationale here is concern for the "collateral consequences" of criminal prosecutions, i.e. the lost jobs that might result from bringing charges against a big company. This was apparently the thinking in the Madoff case as well. As the Times put it in its coverage of the rumored $2 billion settlement:

The government has been reluctant to bring criminal charges against large corporations, fearing that such an action could imperil a company and throw innocent employees out of work. Those fears trace to the indictment of Enron's accounting firm, Arthur Andersen . . .There's only one thing to say about this "reluctance" to prosecute (and the "fear" and "concern" for lost jobs that allegedly drives it): It's a joke.

Yes, you might very well lose some jobs if you go around indicting huge companies on criminal charges. You might even want to avoid doing so from time to time, if the company is worth saving.

But individuals? There's absolutely no reason why the state can't proceed against the actual people who are guilty of crimes.

by Matt Taibbi, Rolling Stone | Read more:

Image: Spencer Platt/Getty Images via:Operation Dead-Mouse Drop

[ed. I hadn't heard about this eradication program until this morning. Apparently, it's still going strong with a fourth drop just recently completed.]

In the U.S. government-funded project, tablets of concentrated acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol, are placed in dead thumb-size mice, which are then used as bait for brown tree snakes.

In the U.S. government-funded project, tablets of concentrated acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol, are placed in dead thumb-size mice, which are then used as bait for brown tree snakes.In humans, acetaminophen helps soothe aches, pains, and fevers. But when ingested by brown tree snakes, the drug disrupts the oxygen-carrying ability of the snakes' hemoglobin blood proteins.

"They go into a coma, and then death," said Peter Savarie, a researcher with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Wildlife Services, which has been developing the technique since 1995 through grants from the U.S. Departments of Defense and Interior.

Only about 80 milligrams of acetaminophen—equal to a child's dose of Tylenol—are needed to kill an adult brown tree snake. Once ingested via a dead mouse, it typically takes about 60 hours for the drug to kill a snake.

"There are very few snakes that will consume something that they haven't killed themselves," added Dan Vice, assistant state director of USDA Wildlife Services in Hawaii, Guam, and the Pacific Islands.

But brown tree snakes will scavenge as well as hunt, he said, and that's the "chink in the brown tree snake's armor." (...)

By contrast, this latest approach aims to take the fight into Guam's jungles, where most of the invasive snakes reside.

A popular misconception about Guam, Vice said, is that the entire island is overrun by brown tree snakes. In reality, most of the snakes are concentrated in the island's jungles, where it is difficult for humans to reach.

"You don't walk out the front door and bump into a snake every morning," Vice said. (...)

Before the laced mice are airdropped, they are attached to "flotation devices" that each consist of two pieces of cardboard joined by a 4-foot-long (1.2-meter-long) paper streamer.

The flotation device was designed to get the bait stuck in upper tree branches, where the brown tree snakes reside, instead of falling to the jungle floor, where the drug-laden mice might inadvertently get eaten by nontarget species, such as monitor lizards.

by Ker Than, National Geographic | Read more:

Image: Vice

Tuesday, December 17, 2013

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)