Saturday, December 21, 2013

Endless Summer: The Next Big Thing in Surfing

Bruce McFarland’s San Diego office is just a skateboard ride from some of California’s prime surf spots. And right now, McFarland is gazing at the perfect wave—a glassy, barreling wall of water. But it’s breaking inside his building, and McFarland, an engineer and surfer, is controlling the wave with an iPad.

Sure, the wave is only three inches tall and is contained in a pint-sized pool built by McFarland’s company, American Wave Machines. But two surf parks deploying the company’s PerfectSwell technology are set to open in Russia and New Jersey, generating four- to six-foot (1.2 to 1.8 meter) waves at the push of a button. “We want to create waves so that anyone, anywhere can surf,” says McFarland.

Sure, the wave is only three inches tall and is contained in a pint-sized pool built by McFarland’s company, American Wave Machines. But two surf parks deploying the company’s PerfectSwell technology are set to open in Russia and New Jersey, generating four- to six-foot (1.2 to 1.8 meter) waves at the push of a button. “We want to create waves so that anyone, anywhere can surf,” says McFarland.

Bringing surfing to the landlocked masses could be the biggest change to hit the sport since Hawaii’s Duke Kahanamoku taught Californians how to ride the waves a century ago. American Wave Machines is just one of half a dozen companies developing artificial wave technology, including a Los Angeles startup founded by 11-time surfing world champion Kelly Slater.

With a mix of hope and hype, the $7 billion surf industry is embracing wave parks as way to grow a flat-lining business. Kids in Kansas and Qatar could become real surfers, not just boardshorts-wearing wannabes. Pro surfing executives, meanwhile, are pushing surf parks as predictable, television-friendly venues to stage competitions as they lobby to make surfing an Olympic sport. “Surf parks will create an entire new generation of aspirational surfers,” says Jess Ponting, director of the Center for Surf Research at San Diego State University. “These new surfers will not just buy for fashion but for equipment as well, and not just in the US but in Russia, China and Europe.”

Surfing has always been as much a way of life as a sport, the exclusive domain of a coastal wave tribe with its own rites and rituals. (Disclosure: I’m one of them.) Now with dozens of surf parks under development worldwide, surfing is about to get Disneyfied—buy a ticket, stand in line, and go for a ride.

Sure, the wave is only three inches tall and is contained in a pint-sized pool built by McFarland’s company, American Wave Machines. But two surf parks deploying the company’s PerfectSwell technology are set to open in Russia and New Jersey, generating four- to six-foot (1.2 to 1.8 meter) waves at the push of a button. “We want to create waves so that anyone, anywhere can surf,” says McFarland.

Sure, the wave is only three inches tall and is contained in a pint-sized pool built by McFarland’s company, American Wave Machines. But two surf parks deploying the company’s PerfectSwell technology are set to open in Russia and New Jersey, generating four- to six-foot (1.2 to 1.8 meter) waves at the push of a button. “We want to create waves so that anyone, anywhere can surf,” says McFarland.Bringing surfing to the landlocked masses could be the biggest change to hit the sport since Hawaii’s Duke Kahanamoku taught Californians how to ride the waves a century ago. American Wave Machines is just one of half a dozen companies developing artificial wave technology, including a Los Angeles startup founded by 11-time surfing world champion Kelly Slater.

With a mix of hope and hype, the $7 billion surf industry is embracing wave parks as way to grow a flat-lining business. Kids in Kansas and Qatar could become real surfers, not just boardshorts-wearing wannabes. Pro surfing executives, meanwhile, are pushing surf parks as predictable, television-friendly venues to stage competitions as they lobby to make surfing an Olympic sport. “Surf parks will create an entire new generation of aspirational surfers,” says Jess Ponting, director of the Center for Surf Research at San Diego State University. “These new surfers will not just buy for fashion but for equipment as well, and not just in the US but in Russia, China and Europe.”

Surfing has always been as much a way of life as a sport, the exclusive domain of a coastal wave tribe with its own rites and rituals. (Disclosure: I’m one of them.) Now with dozens of surf parks under development worldwide, surfing is about to get Disneyfied—buy a ticket, stand in line, and go for a ride.

by Todd Woody, Quartz | Read more:

Image: Wavegarden

NSA Surveillance: 'It's Going to Get Worse'

[ed. See also: The 9 Most Important Recommendations From the President's NSA Surveillance Panel]

Most people would object to the government searching their homes without a warrant. If you were told that that while you are at work, the government is coming into your home every day and searching it without cause, you might be unsettled. You might even think it a violation of your rights specifically, and the bill of rights generally.

Most people would object to the government searching their homes without a warrant. If you were told that that while you are at work, the government is coming into your home every day and searching it without cause, you might be unsettled. You might even think it a violation of your rights specifically, and the bill of rights generally.

But what if the government, in its defence, said: "First of all, we're searching everyone's home, so you're not being singled out. Second, we don't connect your address to your name, so don't worry about it. All we're doing is searching every home in the United States, every day, without exception, and if we find something noteworthy, we'll let you know."

This is the essence of the NSA's domestic spying programme. They are collecting records of every call made in the US, and every call made from the US to recipients abroad. Any number of government agencies can access this data – about who you have called any day, any week, any year. And this information is being kept indefinitely.

This is as clear a violation of the fourth amendment as could be conjured. That amendment protects us against unreasonable search and seizure, and yet the NSA is subjecting all American citizens to both. By collecting records of who we call, the NSA is searching through our private affairs without individualised warrants, and without suspecting the vast majority of citizens of any crime. That is illegal search. And storage of this information constitutes illegal seizure.

A series of revelations about the activities of the NSA has alarmed civil liberties advocates and fans of the constitution, as well as those who value privacy. But until more recently, with the ever-more-astounding revelations made by Edward Snowden, most of the US citizenry has been sanguine. Poll numbers indicate that about 50% of Americans think the NSA's surveillance is just fine, presumably taking comfort in two things: first, in the agency's assertions that it's only the metadata that they're collecting – not the content of the calls; that is, they only know who we have called but not what we've said. Second, General Keith Alexander, the director of the NSA, has said that through this sort of data mining, they have prevented "over 50" terrorist attacks.

The problem here is that two things cannot be proven: we can't prove the assertion that 50 – or any – terrorist attacks have been prevented; and more pressingly, we can't prove that the NSA isn't doing more than collecting this metadata – or won't do more unless its powers are checked.

Most people would object to the government searching their homes without a warrant. If you were told that that while you are at work, the government is coming into your home every day and searching it without cause, you might be unsettled. You might even think it a violation of your rights specifically, and the bill of rights generally.

Most people would object to the government searching their homes without a warrant. If you were told that that while you are at work, the government is coming into your home every day and searching it without cause, you might be unsettled. You might even think it a violation of your rights specifically, and the bill of rights generally.But what if the government, in its defence, said: "First of all, we're searching everyone's home, so you're not being singled out. Second, we don't connect your address to your name, so don't worry about it. All we're doing is searching every home in the United States, every day, without exception, and if we find something noteworthy, we'll let you know."

This is the essence of the NSA's domestic spying programme. They are collecting records of every call made in the US, and every call made from the US to recipients abroad. Any number of government agencies can access this data – about who you have called any day, any week, any year. And this information is being kept indefinitely.

This is as clear a violation of the fourth amendment as could be conjured. That amendment protects us against unreasonable search and seizure, and yet the NSA is subjecting all American citizens to both. By collecting records of who we call, the NSA is searching through our private affairs without individualised warrants, and without suspecting the vast majority of citizens of any crime. That is illegal search. And storage of this information constitutes illegal seizure.

A series of revelations about the activities of the NSA has alarmed civil liberties advocates and fans of the constitution, as well as those who value privacy. But until more recently, with the ever-more-astounding revelations made by Edward Snowden, most of the US citizenry has been sanguine. Poll numbers indicate that about 50% of Americans think the NSA's surveillance is just fine, presumably taking comfort in two things: first, in the agency's assertions that it's only the metadata that they're collecting – not the content of the calls; that is, they only know who we have called but not what we've said. Second, General Keith Alexander, the director of the NSA, has said that through this sort of data mining, they have prevented "over 50" terrorist attacks.

The problem here is that two things cannot be proven: we can't prove the assertion that 50 – or any – terrorist attacks have been prevented; and more pressingly, we can't prove that the NSA isn't doing more than collecting this metadata – or won't do more unless its powers are checked.

by Dave Eggers, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Woody Allen, The Front

Friday, December 20, 2013

The Urbanization of the Eastern Gray Squirrel in the United States

The dominant image of the eastern gray squirrel in early nineteenth-century American culture was as a shy woodland creature that supplied meat for frontiersmen and Indians and game for the recreational hunter but could also become a pest in agricultural areas. Although some other members of the squirrel family, such as the American red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus, also known as the pine squirrel), were present in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American cities, and although small numbers of gray squirrels could be found in woodlands on urban fringes, the gray squirrel was effectively absent from densely settled areas. Sometimes called the “migratory” squirrel, the species was known for unpredictable mass movements by the thousands or even millions across the rural landscape. In The Winning of the West Theodore Roosevelt wrote of the eighteenth-century American backwoodsman's fight against “black and gray squirrels [that] swarmed, devastating the cornfields, and at times gathering in immense companies and migrating across mountain and river.” Crop depredation by gray squirrels—Roosevelt's “black squirrels” were merely a color variant of the species—led residents to set bounties and carry out large-scale squirrel hunts well into the nineteenth century.

The only gray squirrels found in urban areas during this period were pets, such as Mungo, memorialized by Benjamin Franklin in a 1772 epitaph, who escaped from captivity and was killed by a dog after surviving a transatlantic journey to England. In most cases such pets had been taken from nests while young, and many were probably abandoned, killed, or had managed to escape after they matured. Nonetheless, they provided opportunities for urban Americans to form opinions about the habits and character of squirrels that complemented and sometimes contradicted those opinions formed in the context of hunting and farming. Pet squirrels, for example, which were widely available from live-animal dealers, were not shy like the wild squirrels in areas where hunting was common, and they often became importunate in their search for food in pockets and pantries. Familiar within the home, these pets appeared exotic and out of place when they escaped into the urban environment. In 1856 the New-York Daily Times reported that the appearance of an “unusual visitor” in a tree in the park near city hall had attracted a crowd of hundreds; until they were scattered by a policeman, the onlookers cheered the efforts to recapture the pet squirrel.

The first introductions of free-living squirrels to urban centers took place in cities along the Eastern Seaboard between the 1840s and the 1860s. Philadelphia seems to have been the pioneering city, with Boston and New Haven, Connecticut, following soon after. In 1847 three squirrels were released in Philadelphia's Franklin Square and were provided with food and boxes for nesting. Additional squirrels were introduced in the following years, and by 1853 gray squirrels were reported to be present in Independence, Walnut Street, and Logan Squares, where the city supplied nest boxes and food, and where visiting children often provided supplementary nuts and cakes. In 1857 a recent visitor to Philadelphia noted that the city's squirrels were “so tame that they will come and take nuts out of one's hand” and added so much to the liveliness of the parks that “it was a wonder that they are not in the public parks of all great cities.” Boston followed Philadelphia's example by introducing a handful of gray squirrels to Boston Common in 1855, and New Haven had a population of squirrels on its town green by the early 1860s.7

The people who introduced squirrels and other animals to public squares and commons in Philadelphia, Boston, and New Haven sought to beautify and enliven the urban landscape at a time when American cities were growing in geographic extent, population density, and cultural diversity. A typical expression of the motivation behind this effort can be found in an 1853 article in the Philadelphia press describing the introduction of squirrels, deer, and peacocks as steps toward making public squares into “truly delightful resorts, affording the means of increasing enjoyment to the increasing multitudes that throng this metropolis.” In Boston the release of squirrels on the Common was the project of Jerome V. C. Smith, a physician, natural historian, member of the short-lived Native American party, and Boston's mayor from 1854 to 1856. Smith's decision to have Vermont squirrels released on Boston Common was interpreted even by his critics as an attempt to “augment the attractions” of an increasingly leisure-oriented public space. For George Perkins Marsh, the author of Man and Nature, the tameness of the squirrels of the Common was a foretaste of the rewards to be expected when man moderated his destructive behavior toward nature. Like the planting of elms and other shade trees in cities and towns across the United States, the conversion of town commons and greens from pastures and spaces of labor into leisure grounds, and the creation of quasi-rural retreats such as Mount Auburn Cemetery (established outside Boston in the 1830s), the fostering of semitame squirrels in urban spaces aimed to create oases of restful nature in the industrializing city.

by Etienne Benson, Journal of American History | Read more:

Image: via:

A New — and Reversible — Cause of Aging

Researchers have discovered a cause of aging in mammals that may be reversible: a series of molecular events that enable communication inside cells between the nucleus and mitochondria.

As communication breaks down, aging accelerates. By administering a molecule naturally produced by the human body, scientists restored the communication network in older mice. Subsequent tissue samples showed key biological hallmarks that were comparable to those of much younger animals.

As communication breaks down, aging accelerates. By administering a molecule naturally produced by the human body, scientists restored the communication network in older mice. Subsequent tissue samples showed key biological hallmarks that were comparable to those of much younger animals.

“The aging process we discovered is like a married couple — when they are young, they communicate well, but over time, living in close quarters for many years, communication breaks down,” said Harvard Medical School Professor of Genetics David Sinclair, senior author on the study. “And just like with a couple, restoring communication solved the problem.” (...)

As Gomes and her colleagues investigated potential causes for this, they discovered an intricate cascade of events that begins with a chemical called NAD and concludes with a key molecule that shuttles information and coordinates activities between the cell’s nuclear genome and the mitochondrial genome. Cells stay healthy as long as coordination between the genomes remains fluid. SIRT1’s role is intermediary, akin to a security guard; it assures that a meddlesome molecule called HIF-1 does not interfere with communication. (...)

Examining muscle from two-year-old mice that had been given the NAD-producing compound for just one week, the researchers looked for indicators of insulin resistance, inflammation, and muscle wasting. In all three instances, tissue from the mice resembled that of six-month-old mice. In human years, this would be like a 60-year-old converting to a 20-year-old in these specific areas.

One particularly important aspect of this finding involves HIF-1. More than just an intrusive molecule that foils communication, HIF-1 normally switches on when the body is deprived of oxygen. Otherwise, it remains silent. Cancer, however, is known to activate and hijack HIF-1. Researchers have been investigating the precise role HIF-1 plays in cancer growth.

“It’s certainly significant to find that a molecule that switches on in many cancers also switches on during aging,” said Gomes. “We’re starting to see now that the physiology of cancer is in certain ways similar to the physiology of aging. Perhaps this can explain why the greatest risk of cancer is age.”

As communication breaks down, aging accelerates. By administering a molecule naturally produced by the human body, scientists restored the communication network in older mice. Subsequent tissue samples showed key biological hallmarks that were comparable to those of much younger animals.

As communication breaks down, aging accelerates. By administering a molecule naturally produced by the human body, scientists restored the communication network in older mice. Subsequent tissue samples showed key biological hallmarks that were comparable to those of much younger animals.“The aging process we discovered is like a married couple — when they are young, they communicate well, but over time, living in close quarters for many years, communication breaks down,” said Harvard Medical School Professor of Genetics David Sinclair, senior author on the study. “And just like with a couple, restoring communication solved the problem.” (...)

As Gomes and her colleagues investigated potential causes for this, they discovered an intricate cascade of events that begins with a chemical called NAD and concludes with a key molecule that shuttles information and coordinates activities between the cell’s nuclear genome and the mitochondrial genome. Cells stay healthy as long as coordination between the genomes remains fluid. SIRT1’s role is intermediary, akin to a security guard; it assures that a meddlesome molecule called HIF-1 does not interfere with communication. (...)

Examining muscle from two-year-old mice that had been given the NAD-producing compound for just one week, the researchers looked for indicators of insulin resistance, inflammation, and muscle wasting. In all three instances, tissue from the mice resembled that of six-month-old mice. In human years, this would be like a 60-year-old converting to a 20-year-old in these specific areas.

One particularly important aspect of this finding involves HIF-1. More than just an intrusive molecule that foils communication, HIF-1 normally switches on when the body is deprived of oxygen. Otherwise, it remains silent. Cancer, however, is known to activate and hijack HIF-1. Researchers have been investigating the precise role HIF-1 plays in cancer growth.

“It’s certainly significant to find that a molecule that switches on in many cancers also switches on during aging,” said Gomes. “We’re starting to see now that the physiology of cancer is in certain ways similar to the physiology of aging. Perhaps this can explain why the greatest risk of cancer is age.”

by Ana P. Gomes, Kurzweil | Read more:

Image: Ana GomesEBay’s Strategy for Taking On Amazon

There has been much talk about Amazon driving retailers out of business — most recently, and somewhat unbelievably, by proposing to use drones to deliver purchases. For some time now, physical retailers have lived in fear of the various ways in which Amazon can undercut them. If you’re looking for a product that you don’t need to try on or try out, Amazon’s customer analytics and nationwide network of 40-plus enormous fulfillment centers is awfully tough to compete with. And even if you do need to try something on, Amazon conveniently includes a bar-code scanner in its mobile application so you can compare prices while you’re in a store and then have the same item shipped to your home with just a few clicks. (Retailers call this act of checking out products in a store and then buying them online from a different vendor ‘‘showrooming.’’) Amazon holds such sway that for many it’s the default place to buy things online.

And yet online commerce currently accounts for only about 6 percent of all commerce in the United States. We still buy more than 90 percent of everything we purchase offline, often by handing over money or swiping a credit card in exchange for the goods we want. But the proliferation of smartphones and tablets has increasingly led to the use of digital technology to help us make those purchases, and it’s in that convergence that eBay sees its opportunity. As Donahoe puts it: ‘‘We view it actually as and. Not online, not offline: Both.’’

And yet online commerce currently accounts for only about 6 percent of all commerce in the United States. We still buy more than 90 percent of everything we purchase offline, often by handing over money or swiping a credit card in exchange for the goods we want. But the proliferation of smartphones and tablets has increasingly led to the use of digital technology to help us make those purchases, and it’s in that convergence that eBay sees its opportunity. As Donahoe puts it: ‘‘We view it actually as and. Not online, not offline: Both.’’

Most people think of eBay as an online auction house, the world’s biggest garage sale, which it has been for most of its life. But since Donahoe took over in 2008, he has slowly moved the company beyond auctions, developing technology partnerships with big retailers like Home Depot, Macy’s, Toys ‘‘R’’ Us and Target and expanding eBay’s online marketplace to include reliable, returnable goods at fixed prices. (Auctions currently represent just 30 percent of the purchases made at eBay.com; the site sells 13,000 cars a week through its mobile app alone, many at fixed prices.)

Under Donahoe, eBay has made 34 acquisitions over the last five years, most of them to provide the company and its retail partners with enhanced technology. EBay can help with the back end of websites, create interactive storefronts in real-world locations, streamline the electronic-payment process or help monitor inventory in real time. (Outsourcing some of the digital strategy and technological operations to eBay frees up companies to focus on what they presumably do best: Make and market their own products.) In select cities, eBay has also recently introduced eBay Now, an app that allows you to order goods from participating local vendors and have them delivered to your door in about an hour for a $5 fee. The company is betting its future on the idea that its interactive technology can turn shopping into a kind of entertainment, or at least make commerce something more than simply working through price-plus-shipping calculations. If eBay can get enough people into Dick’s Sporting Goods to try out a new set of golf clubs and then get them to buy those clubs in the store, instead of from Amazon, there’s a business model there.

A key element of eBay’s vision of the future is the digital wallet. On a basic level, having a ‘‘digital wallet’’ means paying with your phone, but it’s about a lot more than that; it’s as much a concept as a product. EBay bought PayPal in 2002, after PayPal established itself as a safe way to transfer money between people who didn’t know each other (thus facilitating eBay purchases). For the last several years, eBay has regarded digital payments through mobile devices as having the potential to change everything — to become, as David Marcus, PayPal’s president, puts it, ‘‘Money 3.0.’’

And yet online commerce currently accounts for only about 6 percent of all commerce in the United States. We still buy more than 90 percent of everything we purchase offline, often by handing over money or swiping a credit card in exchange for the goods we want. But the proliferation of smartphones and tablets has increasingly led to the use of digital technology to help us make those purchases, and it’s in that convergence that eBay sees its opportunity. As Donahoe puts it: ‘‘We view it actually as and. Not online, not offline: Both.’’

And yet online commerce currently accounts for only about 6 percent of all commerce in the United States. We still buy more than 90 percent of everything we purchase offline, often by handing over money or swiping a credit card in exchange for the goods we want. But the proliferation of smartphones and tablets has increasingly led to the use of digital technology to help us make those purchases, and it’s in that convergence that eBay sees its opportunity. As Donahoe puts it: ‘‘We view it actually as and. Not online, not offline: Both.’’ Most people think of eBay as an online auction house, the world’s biggest garage sale, which it has been for most of its life. But since Donahoe took over in 2008, he has slowly moved the company beyond auctions, developing technology partnerships with big retailers like Home Depot, Macy’s, Toys ‘‘R’’ Us and Target and expanding eBay’s online marketplace to include reliable, returnable goods at fixed prices. (Auctions currently represent just 30 percent of the purchases made at eBay.com; the site sells 13,000 cars a week through its mobile app alone, many at fixed prices.)

Under Donahoe, eBay has made 34 acquisitions over the last five years, most of them to provide the company and its retail partners with enhanced technology. EBay can help with the back end of websites, create interactive storefronts in real-world locations, streamline the electronic-payment process or help monitor inventory in real time. (Outsourcing some of the digital strategy and technological operations to eBay frees up companies to focus on what they presumably do best: Make and market their own products.) In select cities, eBay has also recently introduced eBay Now, an app that allows you to order goods from participating local vendors and have them delivered to your door in about an hour for a $5 fee. The company is betting its future on the idea that its interactive technology can turn shopping into a kind of entertainment, or at least make commerce something more than simply working through price-plus-shipping calculations. If eBay can get enough people into Dick’s Sporting Goods to try out a new set of golf clubs and then get them to buy those clubs in the store, instead of from Amazon, there’s a business model there.

A key element of eBay’s vision of the future is the digital wallet. On a basic level, having a ‘‘digital wallet’’ means paying with your phone, but it’s about a lot more than that; it’s as much a concept as a product. EBay bought PayPal in 2002, after PayPal established itself as a safe way to transfer money between people who didn’t know each other (thus facilitating eBay purchases). For the last several years, eBay has regarded digital payments through mobile devices as having the potential to change everything — to become, as David Marcus, PayPal’s president, puts it, ‘‘Money 3.0.’’

by Jeff Himmelman, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Grant Cornett. Prop Stylist: Janine Iversen.The Chris McCandless Obsession Problem

Three years ago, Ackermann, 29, and her boyfriend, Etienne Gros, 27, tried to cross the Teklanika River, a couple of miles west from the Savage. They tied themselves to a rope that somebody had run from one bank to the other, to aid such attempts. The Teklanika is powerful in summertime, and about halfway across they lost their footing. The rope dipped into the water, and Ackermann and Gros, still tied on, were pulled under by its weight. Gros grabbed a knife, cut himself loose, and swam to shore. He waded back out to try and rescue Ackermann, but it was too late—she had already drowned. He cut her loose and swam with her body 300 yards downstream, where he dragged her to land on the river’s far shore. His attempts at CPR were useless.

Ackermann, who was from Switzerland, and Gros, a Frenchman, had been hiking the Stampede Trail, a route made famous by Christopher McCandless, who walked it in April 1992. Many people now know about McCandless and how the 24-year-old idealist bailed out of his middle-class suburban life, donated his $24,000 in savings to charity, and embarked on a two-year hitchhiking odyssey that led him to Alaska and the deserted Fairbanks City Transit bus number 142, which still sits, busted and rusting, 20 miles down the Stampede Trail. For 67 days, he ate mostly squirrel, ptarmigan, and porcupine, then he shaved his beard, packed his bag, and started walking back toward the highway. But a raging Teklanika prevented him from crossing, so he returned to the bus and hunkered down. More than a month later, a moose hunter found McCandless’s decomposed body in a sleeping bag inside the bus, where he had starved to death.

This tragic story was told by Jon Krakauer in the January 1993 issue of Outside and later in his bestselling 1997 book, Into the Wild. The book, anda 2007 film directed by Sean Penn, helped elevate the McCandless saga to the status of modern myth. And that, in turn, has given rise to a unique and curious phenomenon in Alaska: McCandless pilgrims, inspired by his story, who are determined to see the bus for themselves. Each year, scores of trekkers journey down the Stampede Trail to visit it. They camp at the bus for days, sometimes weeks, write essays in the various logbooks stowed inside, and ponder the impact that McCandless’s antimaterialist ethic, free-spirited travels, and time in the Alaskan wild has had on how they perceive the world.

Unfortunately, a lot of these people get into trouble, and almost always because of the Teklanika. (...)

Many Alaskans, of course, don’t feel any reverence for McCandless at all. The debate about his worth is often harsh; locals like to float theories about his death wish, his alleged schizophrenia, and his outright foolishness.

The intensity of the debate was rekindled this past September, when Jon Krakauer wrote a story for The New Yorker’s website that revised his theory about how McCandless died. Krakauer argued that it happened because of a neurotoxin called ODAP, which is found in a plant that McCandless was eating and can cause lathyrism, a condition that leads to paralysis. Because the plant is widely considered edible, Krakauer declared that this finding confirms his long-held belief that McCandless wasn’t “as clueless and incompetent as his detractors have made him out to be.”

Plenty of commentary ensued, and plenty of it charged with controversy. “Raised by a game guide in AK my family has ‘respect’ for the land that is different than city kids from ‘outside,’” wrote “kvalvik” in a comment on Krakauer’s article. “Respect for the land comes to mean it will kill you as fast as a slow rabbit in front of a fast fox.”

Few have been as scathingly critical of McCandless’s sympathizers as Craig Medred, an Alaskan who has written numerous pieces about him over the years. In the Alaska Dispatch this fall, Medred, responding to Krakauer’s article, noted the irony of “self-involved urban Americans, people more detached from nature than any society of humans in history, worshipping the noble, suicidal narcissist, the bum, thief and poacher Chris McCandless.”

The pilgrims often encounter similar disdain. I know of beer-toting locals on ATVs who falsely warned three hikers from Phoenix that a “forest fire” was burning between the Teklanika and the bus, urging them to turn back. A pair of hikers I met told me about their experience buying the film’s soundtrack at the Anchorage Barnes and Noble, where one man told them that the bus had been removed. When they went to the Backcountry Information Center at Denali National Park to ask questions about the hike, a ranger told them it wasn’t her job to tell them where the bus was, and that if they didn’t know, they had no business being out there. She said she would end up pulling their bodies out of the river.

Much of the polarization surrounding McCandless stems from a divide in people’s beliefs about what justifies risk-taking in the backcountry. In Alaska, it’s generally considered acceptable to invite risk while making a living on the land—fishing, hunting, logging, mushing, trapping. It is less acceptable to take chances in search of a more philosophical way of life.

by Diana Saverin, Outside | Read more:

Image: Diana Saverin

Seattle: Bertha Hits a Big Object

[ed. Problems, problems... not to mention a potential Ratpocalypse!]

A secret subterranean heart, tinged with mystery and myth, beats beneath the streets in many of the world’s great cities. Tourists seek out the catacombs of Rome, the sewers of Paris and the subway tunnels of New York. Some people believe a den of interstellar aliens lurks beneath Denver International Airport.

Now Seattle, at least for now, has joined that exclusive club.

Now Seattle, at least for now, has joined that exclusive club.

Something unknown, engineers say — and all the more intriguing to many residents for being unknown — has blocked the progress of the biggest-diameter tunnel-boring machine in use on the planet, a high-tech, largely automated wonder called Bertha. At five stories high with a crew of 20, the cigar-shaped behemoth was grinding away underground on a two-mile-long, $3.1 billion highway tunnel under the city’s waterfront on Dec. 6 when it encountered something in its path that managers still simply refer to as “the object.”

The object’s composition and provenance remain unknown almost two weeks after first contact because in a state-of-the-art tunneling machine, as it turns out, you can’t exactly poke your head out the window and look.

“What we’re focusing on now is creating conditions that will allow us to enter the chamber behind the cutter head and see what the situation is,” Chris Dixon, the project manager at Seattle Tunnel Partners, the construction contractor, said in an interview this week. Mr. Dixon said he felt pretty confident that the blockage will turn out to be nothing more or less romantic than a giant boulder, perhaps left over from the Ice Age glaciers that scoured and crushed this corner of the continent 17,000 years ago.

But the unknown is a tantalizing subject. Some residents said they believe, or want to believe, that a piece of old Seattle, buried in the pell-mell rush of city-building in the 1800s, when a mucky waterfront wetland was filled in to make room for commerce, could be Bertha’s big trouble. That theory is bolstered by the fact that the blocked tunnel section is also in the shallowest portion of the route, with the top of the machine only around 45 feet below street grade.

“I’m going to believe it’s a piece of Seattle history until proven otherwise,” said Ann Ferguson, the curator of the Seattle Collection at the Seattle Public Library, who said she held out hope for something of 1890s Klondike Gold Rush vintage, when Seattle became the crazed and booming gateway city to the gold fields of Alaska and Canada. (...)

The tunnel is to run north and south along Elliott Bay from Century Link Field, home of football’s Seahawks, to a point near the Space Needle on the north, allowing demolition of an elevated roadway and improved crosstown foot and bicycle access.

Economics and geology — two key threads of Seattle’s creation — underpin the tunnel’s impetus. Planning for the project began after an earthquake in 2001 revealed seismic vulnerability in the elevated viaduct roadway, which was built in the 1950s. Businesses and real estate interests were then sold on the idea that a tunnel, replacing the viaduct, would open access between downtown and the waterfront.

But unlike, say, Boston or New York, where tunnels are common and bedrock is close to the surface, getting to that end point is messy. Seattle’s underbelly is more like pudding than soil — a slurry of sand, gravel and clay, all jumbled and compressed by the pressures from a 3,000-foot-thick ice sheet that extended as far as Olympia, 50 miles south. A city famous for being wet also has a high water table, only about four to five feet down.

A secret subterranean heart, tinged with mystery and myth, beats beneath the streets in many of the world’s great cities. Tourists seek out the catacombs of Rome, the sewers of Paris and the subway tunnels of New York. Some people believe a den of interstellar aliens lurks beneath Denver International Airport.

Now Seattle, at least for now, has joined that exclusive club.

Now Seattle, at least for now, has joined that exclusive club.Something unknown, engineers say — and all the more intriguing to many residents for being unknown — has blocked the progress of the biggest-diameter tunnel-boring machine in use on the planet, a high-tech, largely automated wonder called Bertha. At five stories high with a crew of 20, the cigar-shaped behemoth was grinding away underground on a two-mile-long, $3.1 billion highway tunnel under the city’s waterfront on Dec. 6 when it encountered something in its path that managers still simply refer to as “the object.”

The object’s composition and provenance remain unknown almost two weeks after first contact because in a state-of-the-art tunneling machine, as it turns out, you can’t exactly poke your head out the window and look.

“What we’re focusing on now is creating conditions that will allow us to enter the chamber behind the cutter head and see what the situation is,” Chris Dixon, the project manager at Seattle Tunnel Partners, the construction contractor, said in an interview this week. Mr. Dixon said he felt pretty confident that the blockage will turn out to be nothing more or less romantic than a giant boulder, perhaps left over from the Ice Age glaciers that scoured and crushed this corner of the continent 17,000 years ago.

But the unknown is a tantalizing subject. Some residents said they believe, or want to believe, that a piece of old Seattle, buried in the pell-mell rush of city-building in the 1800s, when a mucky waterfront wetland was filled in to make room for commerce, could be Bertha’s big trouble. That theory is bolstered by the fact that the blocked tunnel section is also in the shallowest portion of the route, with the top of the machine only around 45 feet below street grade.

“I’m going to believe it’s a piece of Seattle history until proven otherwise,” said Ann Ferguson, the curator of the Seattle Collection at the Seattle Public Library, who said she held out hope for something of 1890s Klondike Gold Rush vintage, when Seattle became the crazed and booming gateway city to the gold fields of Alaska and Canada. (...)

The tunnel is to run north and south along Elliott Bay from Century Link Field, home of football’s Seahawks, to a point near the Space Needle on the north, allowing demolition of an elevated roadway and improved crosstown foot and bicycle access.

Economics and geology — two key threads of Seattle’s creation — underpin the tunnel’s impetus. Planning for the project began after an earthquake in 2001 revealed seismic vulnerability in the elevated viaduct roadway, which was built in the 1950s. Businesses and real estate interests were then sold on the idea that a tunnel, replacing the viaduct, would open access between downtown and the waterfront.

But unlike, say, Boston or New York, where tunnels are common and bedrock is close to the surface, getting to that end point is messy. Seattle’s underbelly is more like pudding than soil — a slurry of sand, gravel and clay, all jumbled and compressed by the pressures from a 3,000-foot-thick ice sheet that extended as far as Olympia, 50 miles south. A city famous for being wet also has a high water table, only about four to five feet down.

by Kirk Johnson, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Washington State Department of TransportationThursday, December 19, 2013

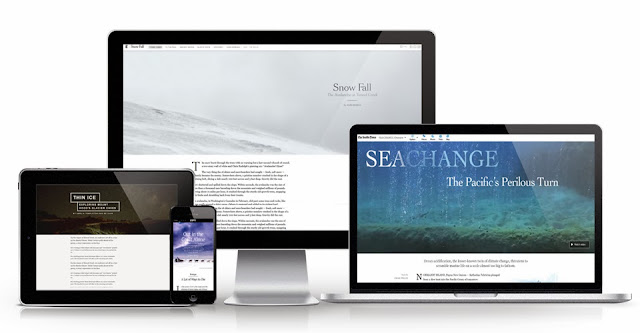

Inspiring Visual Storytelling

Opportunities abound for some creative thinking and here is a round up of some of the best examples of creative online storytelling to inspire you.

So what are the trends in some of the new storytelling projects?

by Heather Bryant, Alaska Media Lab | Read more:

Image: uncredited

R.I.P. The Blog, 1997-2013

Sometime in the past few years, the blog died. In 2014, people will finally notice. Sure, blogs still exist, many of them are excellent, and they will go on existing and being excellent for many years to come. But the function of the blog, the nebulous informational task we all agreed the blog was fulfilling for the past decade, is increasingly being handled by a growing number of disparate media forms that are blog-like but also decidedly not blogs.

Instead of blogging, people are posting to Tumblr, tweeting, pinning things to their board, posting to Reddit, Snapchatting, updating Facebook statuses, Instagramming, and publishing on Medium. In 1997, wired teens created online diaries, and in 2004 the blog was king. Today, teens are about as likely to start a blog (over Instagramming or Snapchatting) as they are to buy a music CD. Blogs are for 40-somethings with kids.I am not generally a bomb-thrower, but I wrote this piece in a deliberately provacative way. Blogs obviously aren’t dead and I acknowledged that much right from the title. I (obviously) think there’s a lot of value in the blog format, even apart from its massive influence on online media in general, but as someone who’s been doing it since 1998 and still does it every day, it’s difficult to ignore the blog’s diminished place in our informational diet. (...)

And yeah, what about Tumblr? Isn’t Tumblr full of blogs? Welllll, sort of. Back in 2005, tumblelogs felt like blogs but there was also something a bit different about them. Today they seem really different…I haven’t thought of Tumblrs as blogs for years…they’re Tumblrs! If you asked a typical 23-year-old Tumblr user what they called this thing they’re doing on the site, I bet “blogging” would not be the first (or second) answer. No one thinks of posting to their Facebook as blogging or tweeting as microblogging or Instagramming as photoblogging. And if the people doing it think it’s different, I’ll take them at their word. After all, when early bloggers were attempting to classify their efforts as something other online diaries or homepages, everyone eventually agreed…let’s not fight everyone else on their choice of subculture and vocabulary.

by Jason Kottke, Kottke.org | Read more:

Facebook Saves Everything

A couple of months ago, a friend of mine asked on Facebook:

A couple of months ago, a friend of mine asked on Facebook:"Do you think that Facebook tracks the stuff that people type and then erase before hitting <enter>? (or the 'post' button)"

Good question.

We spend a lot of time thinking about what to post on Facebook. Should you argue that political point your high school friend made? Do your friends really want to see yet another photo of your cat (or baby)? Most of us have, at one time or another, started writing something and then, probably wisely, changed our minds.

Advertisement

Unfortunately, the code that powers Facebook still knows what you typed – even if you decide not to publish it. It turns out the things you explicitly choose not to share aren't entirely private.

Facebook calls these unposted thoughts "self-censorship", and insights into how it collects these non-posts can be found in a recent paper written by two Facebookers. Sauvik Das, a PhD student at Carnegie Mellon and summer software engineer intern at Facebook, and Adam Kramer, a Facebook data scientist, have put online an article presenting their study of the self-censorship behaviour collected from 5 million English-speaking Facebook users. It reveals a lot about how Facebook monitors our unshared thoughts and what it thinks about them.

The study examined aborted status updates, posts on other people's timelines and comments on others' posts. To collect the text you type, Facebook sends code to your browser. That code automatically analyses what you type into any text box and reports metadata back to Facebook.

Storing text as you type isn't uncommon on other websites. For example, if you use Gmail, your draft messages are automatically saved as you type them. Even if you close the browser without saving, you can usually find a (nearly) complete copy of the email you were typing in your drafts folder. Facebook is using essentially the same technology here. The difference is that Google is saving your messages to help you. Facebook users don't expect their unposted thoughts to be collected, nor do they benefit from it.

It is not clear to the average reader how this data collection is covered by Facebook's privacy policy. In Facebook's Data Use Policy, under a section called "Information we receive and how it is used", it's made clear that the company collects information you choose to share or when you "view or otherwise interact with things". But nothing suggests that it collects content you explicitly don't share. Typing and deleting text in a box could be considered a type of interaction, but I suspect very few of us would expect that data to be saved. When I reached out to Facebook, a representative told me the company believes this self-censorship is a type of interaction covered by the policy.

by Jennifer Golbeck, Sydney Morning Herald | Read more:

Image: Slate

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)