Saturday, April 12, 2014

Cat Shirts By Hiroko Kubota Go Viral

[ed. I think I posted one of these a few months ago.]

Fashion and the Internet have collided spectacularly in this series of awesome embroidered cat shirts by Japanese embroidery artist Hiroko Kubota. The cute kitties, embroidered with great skill and detail, are an unexpected and interesting manifestation of the Internet’s obsession with cats.

In an interview with spoon-tamago.com, Kubota explained that the idea for these shirts happened to come from her son. Because he is of a smaller build, most store-bought clothes wouldn’t fit him, so she often found herself having to make him clothing. At her son’s request, she also began embroidering the shirts with cats, mostly peeking out from the breast pocket.

After posting pictures of the shirts online, they went viral. The majority of her shirts have already sold out, $250-300 price tag notwithstanding. As an excellent embroiderer, she has a ton of other great non-cat-related works as well, all of which can be found on her Etsy store.

In an interview with spoon-tamago.com, Kubota explained that the idea for these shirts happened to come from her son. Because he is of a smaller build, most store-bought clothes wouldn’t fit him, so she often found herself having to make him clothing. At her son’s request, she also began embroidering the shirts with cats, mostly peeking out from the breast pocket.

After posting pictures of the shirts online, they went viral. The majority of her shirts have already sold out, $250-300 price tag notwithstanding. As an excellent embroiderer, she has a ton of other great non-cat-related works as well, all of which can be found on her Etsy store.

by Bored Panda | Read more:

Image: : Hiroko Kubota | Etsy | Flickr Small Plates

[ed. I thought these used to be called appetizers.]

One pizzetta, topped with prosciutto and cut into a few pieces to share. Five charred asparagus stalks underneath a poached egg. A finger of raw sablefish, succumbing in seconds to colliding forks. Toasty breadsticks and sauces for everyone to dip them in.

One pizzetta, topped with prosciutto and cut into a few pieces to share. Five charred asparagus stalks underneath a poached egg. A finger of raw sablefish, succumbing in seconds to colliding forks. Toasty breadsticks and sauces for everyone to dip them in.

If this is dinner, where is the main course?

“Small plates dining” has been making noise at American tapas bars and on high-end tasting menus for at least a decade, but it now appears to be entering the mainstream. Ten years ago, all five of the inaugural James Beard Award nominees for Best New Restaurant hewed more or less to America’s traditional menu format dividing starters and mains; of last year’s nominees, you’ll find only one—San Francisco’s 60-seat Rich Table, which cultivates a spontaneous and communal vibe notwithstanding its traditional menu structure. On the other end of the dining spectrum, big chains like Friday’s and Olive Garden are reworking their menus to feature small plates, too. Underlying this trend is the restauranteurs’ belief that small-plates dining encourages consumers to have a more entertaining night out—and also a more expensive one.

Subtly, “small plates” often means two things at once. The first aspect is “dishes for sharing”—which represents a chance for us restauranteurs to push you, our guests, into more conversation and conviviality. We’ll do whatever we can to get you to have a better time, because success for us requires that we move beyond serving delicious food and into the business of creating compelling experiences. (...)

A “small plates” menu also usually means that the dishes aren’t timed by the kitchen – instead, they’re cooked as soon as possible and brought to their table in whatever order they are completed. This tends to get food to the table as quickly as possible, which makes for happy guests. And, eschewing coursed meals allows some restaurants to save money by not employing an “expediter” to coordinate the cooks’ timing. That makes for one fewer job on the payroll, in an industry where labor is almost always a business’s highest expense.

More importantly, between fast ticket times, tables that turn more quickly, and the rowdy chaos of guests ordering and eating at a rapid pace, small plates offer crowded venues the promise of increased revenue. One San Francisco small-plates chef I know says his guests spend a lot more money in less time, due to their food arriving so quickly. “They keep ordering more and more because they don’t feel full yet,” he told me, “and then suddenly they’re stuffed, they’re ready to leave, and they have a really big tab.”

One pizzetta, topped with prosciutto and cut into a few pieces to share. Five charred asparagus stalks underneath a poached egg. A finger of raw sablefish, succumbing in seconds to colliding forks. Toasty breadsticks and sauces for everyone to dip them in.

One pizzetta, topped with prosciutto and cut into a few pieces to share. Five charred asparagus stalks underneath a poached egg. A finger of raw sablefish, succumbing in seconds to colliding forks. Toasty breadsticks and sauces for everyone to dip them in.If this is dinner, where is the main course?

“Small plates dining” has been making noise at American tapas bars and on high-end tasting menus for at least a decade, but it now appears to be entering the mainstream. Ten years ago, all five of the inaugural James Beard Award nominees for Best New Restaurant hewed more or less to America’s traditional menu format dividing starters and mains; of last year’s nominees, you’ll find only one—San Francisco’s 60-seat Rich Table, which cultivates a spontaneous and communal vibe notwithstanding its traditional menu structure. On the other end of the dining spectrum, big chains like Friday’s and Olive Garden are reworking their menus to feature small plates, too. Underlying this trend is the restauranteurs’ belief that small-plates dining encourages consumers to have a more entertaining night out—and also a more expensive one.

Subtly, “small plates” often means two things at once. The first aspect is “dishes for sharing”—which represents a chance for us restauranteurs to push you, our guests, into more conversation and conviviality. We’ll do whatever we can to get you to have a better time, because success for us requires that we move beyond serving delicious food and into the business of creating compelling experiences. (...)

A “small plates” menu also usually means that the dishes aren’t timed by the kitchen – instead, they’re cooked as soon as possible and brought to their table in whatever order they are completed. This tends to get food to the table as quickly as possible, which makes for happy guests. And, eschewing coursed meals allows some restaurants to save money by not employing an “expediter” to coordinate the cooks’ timing. That makes for one fewer job on the payroll, in an industry where labor is almost always a business’s highest expense.

More importantly, between fast ticket times, tables that turn more quickly, and the rowdy chaos of guests ordering and eating at a rapid pace, small plates offer crowded venues the promise of increased revenue. One San Francisco small-plates chef I know says his guests spend a lot more money in less time, due to their food arriving so quickly. “They keep ordering more and more because they don’t feel full yet,” he told me, “and then suddenly they’re stuffed, they’re ready to leave, and they have a really big tab.”

by Jay Porter, Quartz | Read more:

Image: Reuters/Carlo Allegri

The Sound of Despair

Grunge was often defined by its negativity. It was not a rebellious negativity but a passive negation, a cancelling out. If you asked grunge what it was for, the answer was, supposedly, “Nothing.” The same answer might be given if you asked grunge what it was against. This sentiment was encapsulated by Kurt Cobain’s famous – and perhaps most enduring – lyric, “Oh well, whatever, nevermind.” The sullen indifference (sometimes referred to as irony) of grunge – and the generation that produced it – was mind-boggling and infuriating to the generation of the 1940s, 50s and 60s, generations defined by wars and causes. Grunge had no external wars, no causes that felt immediate enough to be worth fighting for. The grunge generation was said to be internal – in other words, self-absorbed. This was true. Grunge looked mostly inward, as its war was with and about itself. Musically speaking, grunge’s most direct influence was punk. But where the full-blown nihilism and shock of punk still had the touch of theatre and play, grunge was all the more desperate for feeling it had nothing really to show. Punk was shredded, ripped-apart, exploded. Punk was dyed in brilliant colors, adorned with metal and combat boots. Punk was furious. “Kick over the wall, cause government’s to fall,” sang The Clash. Grunge was torn, faded, uncombed. It was the sweater your friend found in a thrift store and annoyingly left on your floor for a month, which you decided to start wearing for lack of initiative to get your own sweater. The image of grunge was, essentially, that of a homeless person.

Punk screamed at you. Grunge called into the desolation. “Oh well, whatever, nevermind.” This lyric is far from a battle cry. This is the song of despair.

The homeless despair of grunge was born of a generation that felt itself on the fringes of American life. Few people could understand how young Americans who lived in relative prosperity and peace could sing about alienation so passionately that it sounded like a crisis. What crisis was there in suburbia, in the innocuous food court of the mall? “Anti-social” and “non-aspirational” were other adjectives used but a better word, perhaps, is “bereft.” What defined grunge most was a longing, a grasping for something essential but inexpressible.

by Stefany Anne Golberg, The Smart Set | Read more:

Image:MTV Unplugged

Punk screamed at you. Grunge called into the desolation. “Oh well, whatever, nevermind.” This lyric is far from a battle cry. This is the song of despair.

The homeless despair of grunge was born of a generation that felt itself on the fringes of American life. Few people could understand how young Americans who lived in relative prosperity and peace could sing about alienation so passionately that it sounded like a crisis. What crisis was there in suburbia, in the innocuous food court of the mall? “Anti-social” and “non-aspirational” were other adjectives used but a better word, perhaps, is “bereft.” What defined grunge most was a longing, a grasping for something essential but inexpressible.

by Stefany Anne Golberg, The Smart Set | Read more:

Image:MTV Unplugged

Health Care Nightmares

When it comes to health reform, Republicans suffer from delusions of disaster. They know, just know, that the Affordable Care Act is doomed to utter failure, so failure is what they see, never mind the facts on the ground.

Thus, on Tuesday, Mitch McConnell, the Senate minority leader, dismissed the push for pay equity as an attempt to “change the subject from the nightmare of Obamacare”; on the same day, the nonpartisan RAND Corporation released a study estimating “a net gain of 9.3 million in the number of American adults with health insurance coverage from September 2013 to mid-March 2014.” Some nightmare. And the overall gain, including children and those who signed up during the late-March enrollment surge, must be considerably larger.

But while Obamacare is looking like anything but a nightmare, there are indeed some nightmarish things happening on the health care front. For it turns out that there’s a startling ugliness of spirit abroad in modern America — and health reform has brought that ugliness out into the open.

But while Obamacare is looking like anything but a nightmare, there are indeed some nightmarish things happening on the health care front. For it turns out that there’s a startling ugliness of spirit abroad in modern America — and health reform has brought that ugliness out into the open.

Let’s start with the good news about reform, which keeps coming in. First, there was the amazing come-from-behind surge in enrollments. Then there were a series of surveys — from Gallup, the Urban Institute, and RAND — all suggesting large gains in coverage. Taken individually, any one of these indicators might be dismissed as an outlier, but taken together they paint an unmistakable picture of major progress. (...)

Republicans clearly have no idea how to respond to these developments. They can’t offer any real alternative to Obamacare, because you can’t achieve the good stuff in the Affordable Care Act, like coverage for people with pre-existing medical conditions, without also including the stuff they hate, the requirement that everyone buy insurance and the subsidies that make that requirement possible. Their political strategy has been to talk vaguely about replacing reform while waiting for its inevitable collapse. And what if reform doesn’t collapse? They have no idea what to do.

At the state level, however, Republican governors and legislators are still in a position to block the act’s expansion of Medicaid, denying health care to millions of vulnerable Americans. And they have seized that opportunity with gusto: Most Republican-controlled states, totaling half the nation, have rejected Medicaid expansion. And it shows. The number of uninsured Americans is dropping much faster in states accepting Medicaid expansion than in states rejecting it.

What’s amazing about this wave of rejection is that it appears to be motivated by pure spite. The federal government is prepared to pay for Medicaid expansion, so it would cost the states nothing, and would, in fact, provide an inflow of dollars. The health economist Jonathan Gruber, one of the principal architects of health reform — and normally a very mild-mannered guy — recently summed it up: The Medicaid-rejection states “are willing to sacrifice billions of dollars of injections into their economy in order to punish poor people. It really is just almost awesome in its evilness.” Indeed.

Thus, on Tuesday, Mitch McConnell, the Senate minority leader, dismissed the push for pay equity as an attempt to “change the subject from the nightmare of Obamacare”; on the same day, the nonpartisan RAND Corporation released a study estimating “a net gain of 9.3 million in the number of American adults with health insurance coverage from September 2013 to mid-March 2014.” Some nightmare. And the overall gain, including children and those who signed up during the late-March enrollment surge, must be considerably larger.

But while Obamacare is looking like anything but a nightmare, there are indeed some nightmarish things happening on the health care front. For it turns out that there’s a startling ugliness of spirit abroad in modern America — and health reform has brought that ugliness out into the open.

But while Obamacare is looking like anything but a nightmare, there are indeed some nightmarish things happening on the health care front. For it turns out that there’s a startling ugliness of spirit abroad in modern America — and health reform has brought that ugliness out into the open.Let’s start with the good news about reform, which keeps coming in. First, there was the amazing come-from-behind surge in enrollments. Then there were a series of surveys — from Gallup, the Urban Institute, and RAND — all suggesting large gains in coverage. Taken individually, any one of these indicators might be dismissed as an outlier, but taken together they paint an unmistakable picture of major progress. (...)

Republicans clearly have no idea how to respond to these developments. They can’t offer any real alternative to Obamacare, because you can’t achieve the good stuff in the Affordable Care Act, like coverage for people with pre-existing medical conditions, without also including the stuff they hate, the requirement that everyone buy insurance and the subsidies that make that requirement possible. Their political strategy has been to talk vaguely about replacing reform while waiting for its inevitable collapse. And what if reform doesn’t collapse? They have no idea what to do.

At the state level, however, Republican governors and legislators are still in a position to block the act’s expansion of Medicaid, denying health care to millions of vulnerable Americans. And they have seized that opportunity with gusto: Most Republican-controlled states, totaling half the nation, have rejected Medicaid expansion. And it shows. The number of uninsured Americans is dropping much faster in states accepting Medicaid expansion than in states rejecting it.

What’s amazing about this wave of rejection is that it appears to be motivated by pure spite. The federal government is prepared to pay for Medicaid expansion, so it would cost the states nothing, and would, in fact, provide an inflow of dollars. The health economist Jonathan Gruber, one of the principal architects of health reform — and normally a very mild-mannered guy — recently summed it up: The Medicaid-rejection states “are willing to sacrifice billions of dollars of injections into their economy in order to punish poor people. It really is just almost awesome in its evilness.” Indeed.

by Paul Krugman, NY Times | Read more:

Image: piperreport.com via:Thursday, April 10, 2014

Dave Matthews and Tim Reynolds

[ed. Note to advertisers just so you know... whoever inserts an insipid advertisement before a YouTube video automatically gets my animosity.]

“Every path is the right path. Everything could’ve been anything else. And it would have just as much meaning.”

~ Mr. Nobody (2009) dir. Jaco Van Dormael

via:

Massive Security Bug In OpenSSL Could Affect A Huge Chunk Of The Internet

[ed. Before you go bonkers, read this... the true spirit of the internet (I hope). Also this: What You Need to Know.]

The same sort of idea can be applied to net security: when all the net security people you know are freaking out, it’s probably an okay time to worry.

The same sort of idea can be applied to net security: when all the net security people you know are freaking out, it’s probably an okay time to worry.This afternoon, many of the net security people I know are freaking out. A very serious bug in OpenSSL — a cryptographic library that is used to secure a very, very large percentage of the Internet’s traffic — has just been discovered and publicly disclosed.

Even if you’ve never heard of OpenSSL, it’s probably a part of your life in one way or another — or, more likely, in many ways. The apps you use, the sites you visit; if they encrypt the data they send back and forth, there’s a good chance they use OpenSSL to do it. The Apache web server that powers something like 50% of the Internet’s web sites, for example, utilizes OpenSSL.

Through a bug that security researchers have dubbed “Heartbleed“, it seems that it’s possible to trick almost any system running any version of OpenSSL from the past 2 years into revealing chunks of data sitting in its system memory.

Why that’s bad: very, very sensitive data often sits in a server’s system memory, including the keys it uses to encrypt and decrypt communication (read: usernames, passwords, credit cards, etc.) This means an attacker could quite feasibly get a server to spit out its secret keys, allowing them to read to any communication that they intercept like it wasn’t encrypted it all. Armed with those keys, an attacker could also impersonate an otherwise secure site/server in a way that would fool many of your browser’s built-in security checks.

And if an attacker was just gobbling up mountains of encrypted data from a server in hopes of cracking it at some point? They may very well now have the keys to decrypt it, depending on how the server they’re attacking was configured (like whether or not it’s set up to utilize Perfect Forward Secrecy.)

by Greg Kumparak, TechCrunch | Read more:

Image: uncredited

Decoding Nature's Soundtrack

[ed. I'm not sold on the practical applications of this type of research, but I'm kind of glad somebody's doing it.]

One of most immediately striking features about Bernie Krause is his glasses. They’re big—not soda-bottle thick, but unusually large, and draw attention to his eyes. Which is ironic, as Krause’s life has been devoted to what he hears, but also appropriate, since it’s the weakness of his eyes that compelled Krause to engage with sound: first with music, and later the music of nature. Nearsighted and astigmatic, Krause has spent most of the last half-century recording biological symphonies to which most of us are deaf. (...)

One of most immediately striking features about Bernie Krause is his glasses. They’re big—not soda-bottle thick, but unusually large, and draw attention to his eyes. Which is ironic, as Krause’s life has been devoted to what he hears, but also appropriate, since it’s the weakness of his eyes that compelled Krause to engage with sound: first with music, and later the music of nature. Nearsighted and astigmatic, Krause has spent most of the last half-century recording biological symphonies to which most of us are deaf. (...)

At this particular moment in Earth’s history—the morning of what some scientists call the Anthropocene, an age in which human influence on natural processes is ubiquitous and immense—we have many tools to measure our ecological impacts: by eye, generally, focusing on particular species or guilds of interest, counting them in the field, peering by satellite at changes in land use, and translating our observations into the language of habitat type and biodiversity.

To Krause, these are measurements best made by listening to natural soundscapes. In a career of listening and recording, he’s amassed a veritable Library of Alexandria of nature’s sounds, and he emphasizes that they’re not merely recordings of individual creatures. The traditional approach of bioacoustics, focusing on single animals and species, is anathema. It’s “decontextualizing and fragmenting,” he says, like trying to extract a single violin from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. “Take an instrument out of the performance, and try to understand the whole performance, and you don’t get very much,” he says.

Inevitably Krause has captured the players—bearded seals with voices that echo geomagnetic storms, baboons booming in granite amphitheaters, a fox kit playing with a microphone—but they’re incidental to recording whole habitats and communities.

In his home studio, perched on an oak-covered hillside in Glen Ellen, Calif., Krause plays me some of his favorites: a Florida swamp, old-growth forest in Zimbabwe, intertidal mangroves in Costa Rica, and a Sierra Nevada mountain meadow. As the sounds pour from speakers mounted above his computer, spectrograms scroll across the screen, depicting visually the timing and frequency of every individual sound. They look like musical scores.

One of most immediately striking features about Bernie Krause is his glasses. They’re big—not soda-bottle thick, but unusually large, and draw attention to his eyes. Which is ironic, as Krause’s life has been devoted to what he hears, but also appropriate, since it’s the weakness of his eyes that compelled Krause to engage with sound: first with music, and later the music of nature. Nearsighted and astigmatic, Krause has spent most of the last half-century recording biological symphonies to which most of us are deaf. (...)

One of most immediately striking features about Bernie Krause is his glasses. They’re big—not soda-bottle thick, but unusually large, and draw attention to his eyes. Which is ironic, as Krause’s life has been devoted to what he hears, but also appropriate, since it’s the weakness of his eyes that compelled Krause to engage with sound: first with music, and later the music of nature. Nearsighted and astigmatic, Krause has spent most of the last half-century recording biological symphonies to which most of us are deaf. (...)At this particular moment in Earth’s history—the morning of what some scientists call the Anthropocene, an age in which human influence on natural processes is ubiquitous and immense—we have many tools to measure our ecological impacts: by eye, generally, focusing on particular species or guilds of interest, counting them in the field, peering by satellite at changes in land use, and translating our observations into the language of habitat type and biodiversity.

To Krause, these are measurements best made by listening to natural soundscapes. In a career of listening and recording, he’s amassed a veritable Library of Alexandria of nature’s sounds, and he emphasizes that they’re not merely recordings of individual creatures. The traditional approach of bioacoustics, focusing on single animals and species, is anathema. It’s “decontextualizing and fragmenting,” he says, like trying to extract a single violin from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. “Take an instrument out of the performance, and try to understand the whole performance, and you don’t get very much,” he says.

Inevitably Krause has captured the players—bearded seals with voices that echo geomagnetic storms, baboons booming in granite amphitheaters, a fox kit playing with a microphone—but they’re incidental to recording whole habitats and communities.

In his home studio, perched on an oak-covered hillside in Glen Ellen, Calif., Krause plays me some of his favorites: a Florida swamp, old-growth forest in Zimbabwe, intertidal mangroves in Costa Rica, and a Sierra Nevada mountain meadow. As the sounds pour from speakers mounted above his computer, spectrograms scroll across the screen, depicting visually the timing and frequency of every individual sound. They look like musical scores.

In each spectrogram, Krause points something out: No matter how sonically dense they become, sounds don’t tend to overlap. Each animal occupies a unique frequency bandwidth, fitting into available auditory space like pieces in an exquisitely precise puzzle. It’s a simple but striking phenomenon, and Krause was the first to notice it. He named it biophony, the sound of living organisms, and to him it wasn’t merely aesthetic. It signified a coevolution of species across deep biological time and in a particular place. As life becomes richer, the symphony’s players find a sonic niche to play without interference.

by Brandon Keim, Nautilus | Read more:

Image: Brandon Keim

In the End, People May Really Just Want to Date Themselves

There’s only one problem with this idea: It’s false. I studied 1 million matches made by the online dating website eHarmony’s algorithm, which aims to pair people who will be attracted to one another and compatible over the long term; if the people agree, they can message each other to set up a meeting in real life. eHarmony’s data on its users contains 102 traits for each person — everything from how passionate and ambitious they claim to be to how much they say they drink, smoke and earn.

The data reveals a clear pattern: People are interested in people like themselves. Women on eHarmony favor men who are similar not just in obvious ways — age, attractiveness, education, income — but also in less apparent ones, such as creativity. Even when eHarmony includes a quirky data point — like how many pictures are included in a user’s profile — women are more likely to message men similar to themselves. In fact, of the 102 traits in the data set, there was not one for which women were more likely to contact men with opposite traits.1

Men were a little more open-minded. For 80 percent of traits, they were more willing to message those different from them. They still preferred mates who were similar in terms of height or attractiveness2, but they cared less about these traits — and they didn’t care much at all about other things women cared about, like similarity in education level or number of photos taken.3They cared less about whether their match shared their ethnicity.4

Women prefer similarity in subtler ways as well: A woman shows a small but highly statistically significant preference for a man who uses similar adjectives to describe himself, with “physically fit,” “intelligent,” “creative” and “funny” having the strongest effects. Men showed no such preference.

by Emma Pierson, 538 | Read more:

Image: uncredited

Living Organ Regenerated for First Time

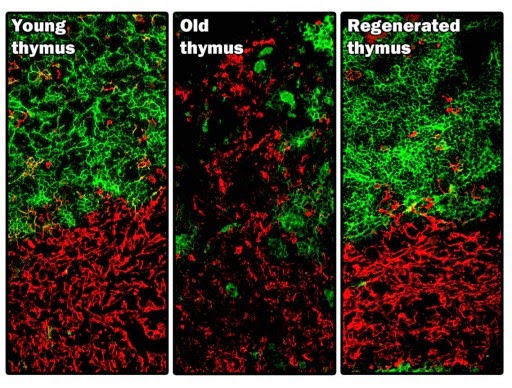

After treatment, the regenerated organ had a structure similar to that found in a young mouse.

The thymus is an organ in the body located next to the heart that produces important immune cells. The advance could pave the way for new therapies for people with damaged immune systems and genetic conditions that affect thymus development.

The function of the thymus was also restored and the mice began making more white blood cells called T cells, which are important for fighting off infection. However, it is not yet clear whether the immune system of the mice was improved.

The study was led by researchers from the Medical Research Council Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh.

The researchers targeted a protein produced by cells of the thymus called FOXN1, which helps to control how important genes are switched on. By increasing levels of FOXN1, the team instructed stem cell-like cells to rebuild the organ.

by Kurzweil AI | Read more:

Image: N. Bredenkamp et al./MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine, University of EdinburgWednesday, April 9, 2014

Washington State to Start Selling Pot in June

Washington State Liquor Board has received a total of 7,046 applications, with 2,206 for retail which they will limit to 334.

The cannabis will be priced at $3 per gram for producers, $6 for processors and a pre-tax $12 per gram for retailers. “The board anticipates tax revenue of up to $2 billion during the first five years as a result of a 25% tax on each level. That’s right, ultimately this cannabis will have been taxed 75% by the time it reaches the customer.”

The cannabis will be priced at $3 per gram for producers, $6 for processors and a pre-tax $12 per gram for retailers. “The board anticipates tax revenue of up to $2 billion during the first five years as a result of a 25% tax on each level. That’s right, ultimately this cannabis will have been taxed 75% by the time it reaches the customer.”

It's, The Masters!

[ed. I know... you're just as excited as I am, it's The Masters! The one tournament each year when the drama is nearly guaranteed on a hushed and breathless Sunday afternoon at Augusta National Golf Club. The dogwoods and azaleas are in full bloom, commercials are kept to a minimum (4 minutes an hour), and the course is fast and tricky. Can't wait.]

We can always be certain of a few things about the Masters Tournament, which starts Thursday at the Augusta National Golf Club: The azaleas will be in bloom. The course will be pristine. The post-tournament sit-down in Butler Cabin will be awkward. But who will win? Let’s see which factors, if any, correlate with success under the Georgia pines.

Full disclosure: Attempting to forecast the outcome of any single golf tournament is, in many ways, a fool’s errand. The PGA Tour’s leading winner in each season since 19801 has averaged 4.6 victories in 21 events, a rate of just under 22 percent. Even Tiger Woods, who may be the greatest golfer of all time, has won only 26 percent of the tournaments he’s entered. The field regularly beats the best golfers in the world, and this is especially true in the tiny sample of a four-round tournament.

Complicating matters, the Masters (one of the more prestigious of the four majors) has seen plenty of fluke winners in recent years, at least based on their perceived status the year before they won the tournament. Going back to 2003, the earliest year for which the PGA Tour website has end-of-year Official World Golf Ranking data, only U.S. Open winners have a lower end-of-year OWGR point average2 than Masters champions in the season before their major victory.3

But despite the inherent uncertainty of golf and especially the Masters, some numbers emerge as predictors of success at Augusta. Specifically, long hitters appear to have an advantage — and pure ball-strikers less so — than would be expected from their performance across all tournaments.

To isolate those predictive factors, I borrowed a technique I first used for last year’s NCAA Giant Killers project at ESPN.com. The idea is to start with a base rating for each player that loosely represents his talent level relative to others’ in the field. Then I look for discrepancies between what that measurement predicted and what happened, and try to determine whether those gaps are related to a particular attribute of a player’s game.

by Neil Paine, 538 | Read more:

Image: Getty Images

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)