When it comes to ad-supported services, pundits everywhere are fond of the adage “If you’re not the customer you’re the product”. It’s interesting, though, how quickly that adage is forgotten when it comes to evaluating the viability of said services.

Twitter is a perfect example. In response to my piece How Facebook Squashed Twitter I got a whole host of responses along the lines of this from John Gruber:

CONSUMER SERVICE CARNAGE

Last Friday LinkedIn suffered one of the worst days the stock market has ever seen, plummeting 40% despite the fact the company beat expectations for both revenue and adjusted earnings; the slide was prompted by significantly lower guidance than investors expected.

The issue for LinkedIn is that a company’s stock price is not a scorecard; rather it is the market’s estimate of a company’s future earnings, and the ratio to which the stock price varies from current earnings is the degree to which investors expect said earnings to grow. In the case of LinkedIn, the company’s relatively mature core business serving recruiters continues to do well; that’s why the company beat estimates. That market, though, has a natural limit, which means growth must be found elsewhere, and LinkedIn hoped that elsewhere would be in advertising. The lower-than-expected estimates and shuttering of Lead Accelerator, LinkedIn’s off-site advertising program (which follows on the heels of LinkedIn’s previous decision to end display advertising), suggested that said growth may not materialize.

Yelp, meanwhile, was only down 11% yesterday after releasing earnings (and issuing guidance) that weren’t that terrible.

The company’s big hit came last summer when the stock plummeted 28% in a single day on, you guessed it, a lower-than-expected forecast, based in part on Yelp’s decision to end its brand advertising program.

Yahoo’s core business, meanwhile, is practically worthless as revenues and earnings continue to decline, and the aforementioned Twitter has seen its valuation slump below $10 billion; both are in stark contrast to the companies each has traditionally been associated with: Google is worth $460 billion (and was briefly the most valuable company in the world) and Facebook is worth $267 billion.

The reason for such a stark bifurcation is, ultimately, all about the “customer”: the advertiser actually buying the ads that underly all of these “free” consumer services.

Twitter is a perfect example. In response to my piece How Facebook Squashed Twitter I got a whole host of responses along the lines of this from John Gruber:

I have argued for years that the fundamental problem is that Twitter is compared to Facebook, and it shouldn’t be. Facebook appeals to billions of people. “Most people”, it’s fair to say. Twitter appeals to hundreds of millions of people. That’s amazing, and there’s tremendous value in that — but it’s no Facebook. Cramming extra features into Twitter will never make it as popular as Facebook — it will only dilute what it is that makes Twitter as popular and useful as it is.From a user’s perspective, I completely agree. But remember the adage: it’s the customers that matter, and from an advertiser’s perspective Facebook and Twitter are absolutely comparable, which is the root of the problem for the latter. Digital advertising is becoming a rather simple proposition: Facebook, Google, or don’t bother.

CONSUMER SERVICE CARNAGE

Last Friday LinkedIn suffered one of the worst days the stock market has ever seen, plummeting 40% despite the fact the company beat expectations for both revenue and adjusted earnings; the slide was prompted by significantly lower guidance than investors expected.

The issue for LinkedIn is that a company’s stock price is not a scorecard; rather it is the market’s estimate of a company’s future earnings, and the ratio to which the stock price varies from current earnings is the degree to which investors expect said earnings to grow. In the case of LinkedIn, the company’s relatively mature core business serving recruiters continues to do well; that’s why the company beat estimates. That market, though, has a natural limit, which means growth must be found elsewhere, and LinkedIn hoped that elsewhere would be in advertising. The lower-than-expected estimates and shuttering of Lead Accelerator, LinkedIn’s off-site advertising program (which follows on the heels of LinkedIn’s previous decision to end display advertising), suggested that said growth may not materialize.

Yelp, meanwhile, was only down 11% yesterday after releasing earnings (and issuing guidance) that weren’t that terrible.

The company’s big hit came last summer when the stock plummeted 28% in a single day on, you guessed it, a lower-than-expected forecast, based in part on Yelp’s decision to end its brand advertising program.

Yahoo’s core business, meanwhile, is practically worthless as revenues and earnings continue to decline, and the aforementioned Twitter has seen its valuation slump below $10 billion; both are in stark contrast to the companies each has traditionally been associated with: Google is worth $460 billion (and was briefly the most valuable company in the world) and Facebook is worth $267 billion.

The reason for such a stark bifurcation is, ultimately, all about the “customer”: the advertiser actually buying the ads that underly all of these “free” consumer services.

by Ben Thompson, Stratechery | Read more:

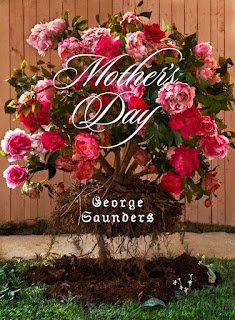

Image: uncredited