Thursday, November 21, 2019

Meals on Broken Wheels

What do DoorDash, GrubHub, Postmates and Uber Eats have in common with Lassie? Nothing. They’re dogs; Lassie’s a superstar. What do they have in common with each other? Everything. They take the world’s second oldest profession — Babylonia had delivery boys — sprinkle it with tech dust, click their ruby slippers, chant “There’s no place like Silicon Valley” and hope to become unicorns. (By the way, since unicorns are entirely mythical, wouldn’t the Valley be wise to pick another moniker for its wannabe superstars?)

There’s no secret to success in tech. But like hitting a 98 mph fastball, it’s easy to describe, nearly impossible to do: Create a great product that can scale. Even better if you can build a patent moat around it. If, after five hard years of R&D, you create killer software at a cost of $100 million, then the first product you ship for $1,000 comes at a loss of $99.99 million. But by the time you’ve sold your millionth unit at almost no additional cost, you’ve grossed a billion. That’s scale.

Here’s the rub: You can scale intellectual property, you can’t scale labor. Your millionth pizza costs as much to deliver as your first.

Yet the meal-delivery guys claim they will scale when they create a critical mass. They will have the density they need to become profitable (none are yet) if they can somehow bag a huge market share. The density argument goes like this: if we can deliver enough meals in a given trade area, we can be like the post office in terms of efficiency (yes, the post office, I’m not being ironic). Nice idea, but it doesn’t wash.

The post office is a route business—your mail carrier hits the same couple hundred houses on the identical route every day. That beats 200 homeowners making 200 trips to the post office.

Meal delivery is a discrete business. No one else in your zip code is ordering spaghetti Bolognese from Trattoria Pastaria at 6:30 on a Tuesday evening. Whether the Uber Eats guy drives to the restaurant or you do, it’s the same (except the food is hotter if you do it yourself). There is no way to string that discrete delivery into an efficient, cost-effective route. To that point, old-school pizza joints average about 2 deliveries an hour and their drivers start at the restaurant. Can a free-floating DoorDasher do more than two an hour?

In short, Mount Everest is scalable, meal-delivery companies are not.

This claim of eventual profitability calls to mind the very old joke about the jeweler who sold his diamonds below cost, losing a little on each sale. “I make it up in volume,” he said. He didn’t and neither will the meal-delivery companies.

Let’s get specific. DoorDash, Postmates and Uber Eats all deliver for McDonald’s. According to that most reliable of all sources, the internet, they charge about $5 to deliver your burger and fries. And it takes about 30 minutes from the time you order to delivery. This means that, like pizza, the driver can do about two trips an hour. This is a truly great service for the consumer too stoned to get his own milkshake at midnight.

But there is no way, no way, in the world this can be profitable for the meal-delivery companies (or the restaurants if they do it themselves). Ten bucks an hour won’t even pay for the driver’s gas and minimum wage, let alone his incidental car costs. What’s left for DoorDash on ten bucks an hour? Nothing.

There’s no secret to success in tech. But like hitting a 98 mph fastball, it’s easy to describe, nearly impossible to do: Create a great product that can scale. Even better if you can build a patent moat around it. If, after five hard years of R&D, you create killer software at a cost of $100 million, then the first product you ship for $1,000 comes at a loss of $99.99 million. But by the time you’ve sold your millionth unit at almost no additional cost, you’ve grossed a billion. That’s scale.

Here’s the rub: You can scale intellectual property, you can’t scale labor. Your millionth pizza costs as much to deliver as your first.

Yet the meal-delivery guys claim they will scale when they create a critical mass. They will have the density they need to become profitable (none are yet) if they can somehow bag a huge market share. The density argument goes like this: if we can deliver enough meals in a given trade area, we can be like the post office in terms of efficiency (yes, the post office, I’m not being ironic). Nice idea, but it doesn’t wash.

The post office is a route business—your mail carrier hits the same couple hundred houses on the identical route every day. That beats 200 homeowners making 200 trips to the post office.

Meal delivery is a discrete business. No one else in your zip code is ordering spaghetti Bolognese from Trattoria Pastaria at 6:30 on a Tuesday evening. Whether the Uber Eats guy drives to the restaurant or you do, it’s the same (except the food is hotter if you do it yourself). There is no way to string that discrete delivery into an efficient, cost-effective route. To that point, old-school pizza joints average about 2 deliveries an hour and their drivers start at the restaurant. Can a free-floating DoorDasher do more than two an hour?

In short, Mount Everest is scalable, meal-delivery companies are not.

This claim of eventual profitability calls to mind the very old joke about the jeweler who sold his diamonds below cost, losing a little on each sale. “I make it up in volume,” he said. He didn’t and neither will the meal-delivery companies.

Let’s get specific. DoorDash, Postmates and Uber Eats all deliver for McDonald’s. According to that most reliable of all sources, the internet, they charge about $5 to deliver your burger and fries. And it takes about 30 minutes from the time you order to delivery. This means that, like pizza, the driver can do about two trips an hour. This is a truly great service for the consumer too stoned to get his own milkshake at midnight.

But there is no way, no way, in the world this can be profitable for the meal-delivery companies (or the restaurants if they do it themselves). Ten bucks an hour won’t even pay for the driver’s gas and minimum wage, let alone his incidental car costs. What’s left for DoorDash on ten bucks an hour? Nothing.

by John E. McNellis, Wolf Street | Read more:

[ed. See also: Silicon Valley Is Slowing, Whether for a Quick Breather or Extended Time-Out, I Have No Idea (Wolf Street).]

How Home Delivery Reshaped the World

A lot of attention has rightly been paid to the toll that fulfilling our orders takes upon workers in warehouses or drivers in delivery vans. But additionally, as our purchases hurtle towards us in ever-higher volumes and at ever-faster rates, they exert an unseen, transformative pressure – on infrastructure, on cities, on the companies themselves. “The customer is putting an enormous strain on the supply chain,” said James Nicholls, a managing partner at Stephen George + Partners, an industrial architecture firm. “Especially if you are ordering a thing in five different colours, trying them all on, and sending four of them back.”

How the pressures of home delivery reorder the world can be understood best through the “last mile” – which is not strictly a mile but the final leg that a parcel travels from, say, Magna Park 3 to a bedsit in Birmingham. The last mile obsesses the delivery industry. No one in the day-to-day hustle of e-commerce talks very seriously about the kind of trial-balloon gimmicks that claim to revolutionise the last mile: deliveries by drones and parachutes and autonomous vehicles, zeppelin warehouses, robots on sidewalks. Instead, the most pressing last-mile problems feel basic, low-concept, old-school. How best to pack a box. How to beat traffic. What to do when a delivery driver rings the doorbell and no one is home. What to do with the forests of used cardboard. In home delivery, the last mile has become the most expensive and difficult mile of all. (...)

E-commerce has turned even the laying of a floor into a fiendishly involved business. The concrete floors of B2B sheds were already being built to an exacting degree of flatness, calibrated using lasers, so that forklifts would not teeter while lifting pallets to the highest shelves. As the urgency of home delivery grew, robotic pickers began to populate e-commerce sheds, so the floors had to be flatter still – first poured to a standard called FM2, and the robots’ aisles then ground down further to FM1. In these “superflat floors”, even a 10th of a millimetre matters. The merest waywardness in a robotic picker can tangle up the whole shed’s operations and delay thousands of deliveries.

But as delivery schedules have dwindled into hours, even the gigantic warehouse full of stuff in a central place such as the triangle is proving insufficient. Now, companies also need smaller distribution centres around the country, to respond rapidly to orders and to abbreviate the last mile as much as possible. These smaller sheds cannot stock as much, but the foresight of data analytics now makes a keen strategic efficiency possible. Woodbridge remembers how, while visiting a shipping provider’s facility a few years ago, he saw a curious pile of Amazon parcels.

“I said: ‘They haven’t got any names on them. Who are they for?’” he told me. The packages held video games, it turned out: the newest edition of the annual Fifa series by Electronic Arts. “And they said: ‘Amazon knows, if you’ve bought the game for the last three years or whatever, that you’re likely to buy it again.’ So they’ve already got it packaged up for you, waiting for you to press the button. You do that, and they’ll stick your name on it, and it’s gone.”

How our home delivery habit reshaped the world (The Guardian)

Image: AP S/Alamy

Wednesday, November 20, 2019

No One Likes the Real Me!

Hi Polly,

I desperately need some practical advice about a very impractical life problem. That problem being, I don’t care about my life. To be clear, I don’t want to stop living, and my life could probably be worse. But every day, I think about the things I need to do in order to succeed in college and build a career, and though I try as hard as I can, I just do not care. It’s like pulling teeth to get myself to study or to apply for jobs or to network with people, because I have to fight through the voice in my head screaming that this stuff doesn’t matter.

My real problem is, I start thinking about what could even come after college, and my whole mind goes blank. My degree in communications may eventually get me a better job, but due to my utter lack of charisma and drive, it may not. You know the saying, “It takes a village”? Well, I agree. No one gets anywhere without the support of other people. But in order for people to support you, they need to like you, and I’m not very likable. It’s really hard for me to connect with others on a genuine level. I love my parents, but due to differences in religion, sexuality, and life goals, we tend to keep our conversations light both in content and in frequency. When I make friends, they usually decide I’m not what they signed up for and leave, or I ask too much of them and drive them away. Dating has been a similar disaster. I was okay at peer tutoring, and I was okay at retail, but at a certain point, I just couldn’t turn on whatever it is you turn on to make people feel like the interaction was worthwhile.

It’s not that I hate other people, or that I can’t talk to them. It’s just that it feels terrible the whole time.

I am not prepared for a world of constant communication, of marketing myself. And the older I get, the more I see that I’ll never escape the need to be something more palatable in order to be supported emotionally, and also in order to get hired and continue eating. I’m not trying to be a bitch. I really, truly believe in love and friendship and the power of human connection. But I also really, truly have to make people like me so I can pay my rent. And I have proof that people don’t like my natural personality. So here I am trying to find meaning in a world that, as a whole, doesn’t like the introverted overthinker, the too-honest but also too-distant person that I really am — and also doesn’t really like the person I try to be for its benefit. There is no way for me to win, no matter what job I have or what classes I take or what I do with my life.

Do you have any tips for dealing with a world like this? Because I’m absolutely exhausted.

I Want to Be Me (But I Want to Eat)

Dear IWTBM,

Cultivate your faith in the world. There is love for you here.

Yes, plenty of people dislike introverted overthinkers who are too honest and also too distant. The worst possible thing that someone like that can do, though, is pretend to be an upbeat extrovert for the sake of others. Introverted overthinkers with confessional impulses have to learn to love and accept who they are. Then they can be themselves and other people will enjoy them, embrace them, envy their honesty, admire their ideas, adore their unique perspectives, and savor their company.

Right now, you’re taking your stressful circumstances (working your way through college) and your very sensitive, alienated perspective on the world (everyone is predictable and bubbly and abhors complexity) and you’re bundling them together into a dreary outlook for your future. But you don’t even know what life after college will be like. Life in a college town among college students, working a menial job, does not offer an accurate snapshot of life anywhere else. I grew up in a college town and I’ve worked many, many menial jobs. Extrapolating from this habitat is a big mistake. Keep your mind open, because the world is much more wild and interesting than you can imagine.

I say this all the time, and I never stop believing it: Unless you’re naturally a sociopath or predator, you can be yourself around other people — even people who are different from you — and many of them will love you for it. The ones who don’t aren’t some bellwether of your success as a human being. Cast them aside and sally forth with an open heart.

Your primary problem right now is your firm belief that people hate your “natural” personality. You are certain, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that you’re broken and unlovable and you have to hide the truth about who you are. Many people believe this at your age. Some of the people who seem to be rejecting you also believe this about themselves. Instead of fixating on what you’re doing wrong in every interaction, use your sensitive nature to be still and tune into how insecure and ashamed the people around you are. Observe the jittery robots in your midst. Half of the people you encounter as extroverted are secretly introverts. Half of the people you experience as confident are massively insecure. Look for a reflection of your natural, too honest, too distant self hiding behind their masks. It’s there.

It feels terrible to talk to people because you’re trying to make them like you. The second you remove that imperative from your mind, things will improve. You say people don’t like your “natural” personality, but has anyone really experienced it? As long as you’re anxious over how much people like you, trust me, your natural personality is still hidden. The only way your real personality will show is if you connect with other people without fear.

In order to get there, you have to do a bunch of tough things at once. You have to stop obsessing about what people think of you. You have to stop trying so hard to impress people. You have to stop overexplaining everything you do to other people. You have to lower your expectations of others. You have to accept people for who they are (giving them the acceptance that you don’t give yourself yet). You have to listen closely to others instead of remaining preoccupied with how you’re coming across. And you have to speak honestly about your goals, desires, challenges, and flaws.

To someone who’s been trying too hard for years, that probably sounds like an enormous amount of work. But you can also take a short cut: Stop trying to impress people, full stop. Let go of your narrative that you’re unlikable. Let go of the false belief that you’ll only make friends and make a living if you bullshit people. Abandon this notion that no one has ever liked you. You are coating the world in darkness, out of fear and stress and loneliness. Try a new path forward instead. (...)

What people dislike about you, once they become your friend, is not your natural self. What they dislike is how hard you work, and how much compensatory devotion you expect from them, prematurely, and how angry and rejected you feel when someone lets you down, and how determined you are to hide your true self, even as you demand that other people show their true selves. No matter who you are naturally, as long as you’re pissed off and you’re trying too hard and you’re also fearful and sad and half-hiding, people won’t like you. Even if you think you’re playing the part of the enthusiastic, fun, thoroughly chill new friend convincingly, most people see through it. High-strung people can’t hide themselves that easily — a fact that, once we start to notice it, makes us even more high-strung, and even more convinced that there’s something deeply wrong with us.

by Heather Havrilesky, The Cut | Read more:

Image: SG Wildlife Photography / 500px/Getty Images/500px PlusDisney Says It Raised Park Ticket Prices to Improve Your Experience

The successful launch of the Disney+ streaming service has been getting a lot of attention and boosting the Walt Disney Company’s stock price, but that’s not the only bright spot in the company’s recent performance. When Disney announced quarterly earnings two weeks ago, it said its “parks, products and experiences” segment generated 8 percent more revenue and 17 percent more operating income in this year’s third calendar quarter than in the same quarter a year earlier.

How did the company make more money at its theme parks? Mostly by raising prices. But Disney says it’s for your own good.

Until 2016, Disney park ticket prices were the same every day, but now prices are tiered based on they day you visit into “value,” “regular,” and “peak.” The company frames this as a matter of “yield management” — using low prices to push guests to visit on off-season Tuesdays and high prices to make the parks less oppressively crowded on summer Saturdays — but in practice, Disneyland’s base ticket price on “value” days ($104) is sharply higher than the any-day ticket price just a few years ago ($87 in 2012). Plus, there were only 47 value-price days in 2019 and the last one was May 23, so for the rest of the year, if you’re over the age of 9, you won’t be getting into Disneyland for less than $129. On peak days, that will be $149.

These high prices are one factor that has suppressed crowds, at least at Disneyland in California. Back in July, the Orange County Register reported on an “apparent scarcity of visitors” that made this summer “the best time to visit Disneyland.” That seems to be holding true in the fall: I visited Disneyland on Tuesday; my one-day park ticket was a whopping $194, and, true to Disney executives’ claims, my guest experience was indeed enhanced by what appeared to be relatively limited crowds.

The base ticket price on Tuesday was $129, so how did I end up paying $194? Because I paid $50 for the privilege of visiting both Disneyland Park and Disney California Adventure on the same ticket, and another $15 for MaxPass, a feature that allowed me to make ride reservations through the Disneyland smartphone app. Tuesday was not a “peak” day; if I visited again this Saturday, the same ticket package would cost me $214.

But for this high price, I did get an experience that was a lot more seamless with a lot less waiting than I remember from Disney parks in my childhood, and not just because of relatively light crowds. The MaxPass offering meant my friends and I could take out our phones at noon, standing inside the new, Star Wars–themed Galaxy’s Edge area at Disneyland Park, and make a reservation for a 6:30 p.m. ride on Radiator Springs Racers, the Cars-themed attraction that draws the biggest crowds at California Adventure, about a half-mile away. When we got to Radiator Springs hours later, after many intervening rides and a few cocktails, we waited less than ten minutes to board, even as the standby rider line (for those without reservations) had a posted waiting time of 80 minutes.

If we hadn’t bought the add-ons, we wouldn’t have been able to get to all the rides we wanted to in a single day, and we would have spent a lot more time waiting in lines and shuffling around to obtain FastPass reservation tickets. And of course, if ticket prices had stayed lower, the lines might have been longer everywhere — as it stood, we were able to walk onto Space Mountain (recently rechristened Hyperspace Mountain) around 11 a.m. with no reservation and a less-than 20-minute wait.

Disney has not gone as far as its competitors in letting customers pay to avoid waiting. Unlike at Six Flags, which has tiered ticket pricing, where the more you pay the less you wait, Disney would not be so gauche as to use such an in-your-face system to rank guest importance. All guests at Disney parks are special, and therefore all guests are welcome to use the FastPass system to reserve a limited number of rides in advance and come back when it’s their turn without waiting in line.

But there are subtler ways Disney gives advantages to customers it values more: Paying for MaxPass makes it easier to use FastPass more effectively, because you can use a phone app instead of visiting physical reservation kiosks; on certain days, paying Disney hotel guests can enter the parks before they open to the public and stay after they close; in Florida, hotel guests can make ride reservations far in advance of their vacations; and for hundreds of dollars an hour, you even can hire a VIP guide to escort your family to the front of the line. And the main way Disney has been stratifying its guests is an invisible one: By raising ticket prices, it is keeping some potential guests out of the parks altogether.

by Josh Barro, The Intelligencer | Read more:

Image: Salvatore Romano/NurPhoto via Getty ImagesSecretive Energy Startup Achieves Solar Breakthrough

A secretive startup backed by Bill Gates has achieved a solar breakthrough aimed at saving the planet.

Heliogen, a clean energy company that emerged from stealth mode on Tuesday, said it has discovered a way to use artificial intelligence and a field of mirrors to reflect so much sunlight that it generates extreme heat above 1,000 degrees Celsius.

Essentially, Heliogen created a solar oven — one capable of reaching temperatures that are roughly a quarter of what you'd find on the surface of the sun.

The breakthrough means that, for the first time, concentrated solar energy can be used to create the extreme heat required to make cement, steel, glass and other industrial processes. In other words, carbon-free sunlight can replace fossil fuels in a heavy carbon-emitting corner of the economy that has been untouched by the clean energy revolution.

The breakthrough means that, for the first time, concentrated solar energy can be used to create the extreme heat required to make cement, steel, glass and other industrial processes. In other words, carbon-free sunlight can replace fossil fuels in a heavy carbon-emitting corner of the economy that has been untouched by the clean energy revolution.

"We are rolling out technology that can beat the price of fossil fuels and also not make the CO2 emissions," Bill Gross, Heliogen's founder and CEO, told CNN Business. "And that's really the holy grail."

Heliogen, which is also backed by billionaire Los Angeles Times owner Patrick Soon-Shiong, believes the patented technology will be able to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions from industry. Cement, for example, accounts for 7% of global CO2 emissions, according to the International Energy Agency.

"Bill and the team have truly now harnessed the sun," Soon-Shiong, who also sits on the Heliogen board, told CNN Business. "The potential to humankind is enormous. ... The potential to business is unfathomable." (...)

Heliogen uses computer vision software, automatic edge detection and other sophisticated technology to train a field of mirrors to reflect solar beams to one single spot.

"If you take a thousand mirrors and have them align exactly to a single point, you can achieve extremely, extremely high temperatures," Gross said, who added that Heliogen made its breakthrough on the first day it turned its plant on.

Heliogen said it is generating so much heat that its technology could eventually be used to create clean hydrogen at scale. That carbon-free hydrogen could then be turned into a fuel for trucks and airplanes.

"If you can make hydrogen that's green, that's a gamechanger," said Gross. "Long term, we want to be the green hydrogen company."

by Matt Egan, CNN Business | Read more:

Image: Heliogen

[ed. Perhaps other (less laudable) uses as well. See also: Company claims breakthrough in concentrating the Sun’s rays (Ars Technica); and, per the law of unintended consequences: From the Walkie Talkie to the Death Ray Hotel (Guardian). Update: A Solar 'Breakthrough' Won't Solve Cement's Carbon Problem (Wired).]

Heliogen, a clean energy company that emerged from stealth mode on Tuesday, said it has discovered a way to use artificial intelligence and a field of mirrors to reflect so much sunlight that it generates extreme heat above 1,000 degrees Celsius.

Essentially, Heliogen created a solar oven — one capable of reaching temperatures that are roughly a quarter of what you'd find on the surface of the sun.

The breakthrough means that, for the first time, concentrated solar energy can be used to create the extreme heat required to make cement, steel, glass and other industrial processes. In other words, carbon-free sunlight can replace fossil fuels in a heavy carbon-emitting corner of the economy that has been untouched by the clean energy revolution.

The breakthrough means that, for the first time, concentrated solar energy can be used to create the extreme heat required to make cement, steel, glass and other industrial processes. In other words, carbon-free sunlight can replace fossil fuels in a heavy carbon-emitting corner of the economy that has been untouched by the clean energy revolution."We are rolling out technology that can beat the price of fossil fuels and also not make the CO2 emissions," Bill Gross, Heliogen's founder and CEO, told CNN Business. "And that's really the holy grail."

Heliogen, which is also backed by billionaire Los Angeles Times owner Patrick Soon-Shiong, believes the patented technology will be able to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions from industry. Cement, for example, accounts for 7% of global CO2 emissions, according to the International Energy Agency.

"Bill and the team have truly now harnessed the sun," Soon-Shiong, who also sits on the Heliogen board, told CNN Business. "The potential to humankind is enormous. ... The potential to business is unfathomable." (...)

Heliogen uses computer vision software, automatic edge detection and other sophisticated technology to train a field of mirrors to reflect solar beams to one single spot.

"If you take a thousand mirrors and have them align exactly to a single point, you can achieve extremely, extremely high temperatures," Gross said, who added that Heliogen made its breakthrough on the first day it turned its plant on.

Heliogen said it is generating so much heat that its technology could eventually be used to create clean hydrogen at scale. That carbon-free hydrogen could then be turned into a fuel for trucks and airplanes.

"If you can make hydrogen that's green, that's a gamechanger," said Gross. "Long term, we want to be the green hydrogen company."

by Matt Egan, CNN Business | Read more:

Image: Heliogen

[ed. Perhaps other (less laudable) uses as well. See also: Company claims breakthrough in concentrating the Sun’s rays (Ars Technica); and, per the law of unintended consequences: From the Walkie Talkie to the Death Ray Hotel (Guardian). Update: A Solar 'Breakthrough' Won't Solve Cement's Carbon Problem (Wired).]

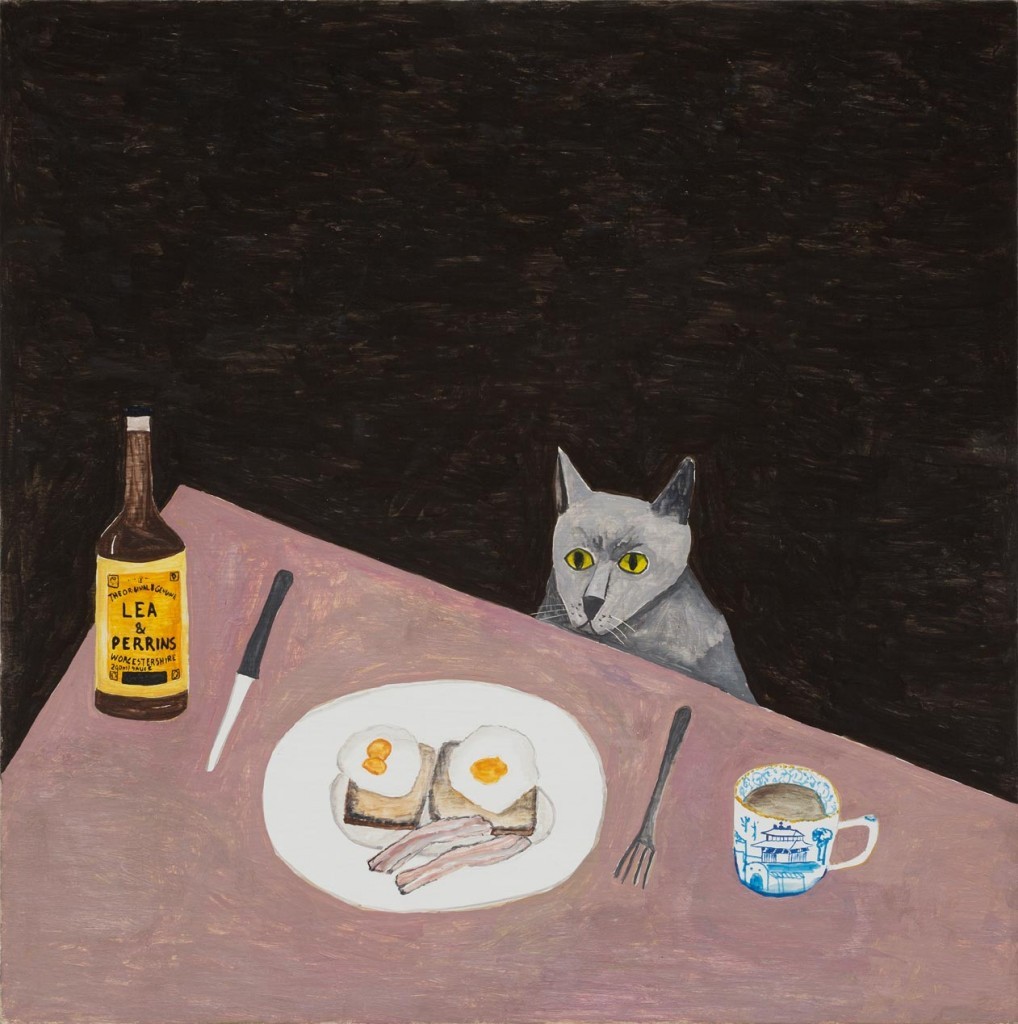

The Crying Game

I suppose some people can weep softly and become more beautiful, but after a real cry, most people are hideous, as if they’ve grown a spare and diseased face beneath the one you know, leaving very little room for the eyes. Or they look as if they’ve been beaten. We look. I look. Once, in fifth grade, I cried at school for a reason I cannot recall, and afterward a popular boy—rattail, skateboard—told me I looked like a druggie, and I was so pleased to be seen I made him repeat it.

•••

Ovid would prefer that I and other women restrain ourselves:

The length of the cry matters. I especially value an extended session, which gives me time to become curious, to look in the mirror, to observe my physical sadness. A truly powerful cry can withstand even this scientific activity. You lurch toward the bathroom, head hunched over, tucked in, and then gather your nerve to lift your gaze toward the mirror, where you see your hiccoughing breath shake your shoulders, your nose like a lifelong drunk’s. It may interest you for a while to touch your swollen face, to peer into one bloodshot eye and another, but the beauty’s really in the movement, in watching your mouth try to swallow despair. It is not easy, after looking, to convince the crying you mean it no harm, but with quiet and with patience—you are Jane Goodall with the chimpanzees—the crying will slowly get used to you. It will return.

•••

To cry or not to cry is sometimes a choice, and no telling which is the better. Not true—if you are alone, or with only one other, cry. To cry with more people present, concludes the International Study of Adult Crying, can lead to a worsening mood, though that may depend on others’ reactions. You can be made to feel ashamed. Most frequently criers report others responding with compassion, or what the study categorizes as “comfort words, comfort arms, and understanding.” If you are alone, comfort arms are still available; you hold yourself together.

•••

It is fortunate to have a nose. Hard to feel you are too tragic a figure when the tears mix with snot. There is no glamour in honking.

•••

Once I was unexpectedly dumped in public. A campus parking lot one afternoon. I put all my crying into my mouth, felt it shake while I stalked to the car, inside which I let the crying move north to my eyes and south to my heaving gut. The car is a private crying area. If you see a person crying near a car, you may need to offer help. If you see a person crying inside a car, you know they are already held.

by Heather Christle, Bookforum | Read more:

•••

Ovid would prefer that I and other women restrain ourselves:

There is no limit to art: in weeping, you need to•••

be comely,

Learn how to turn on the tears still keeping

proper control.

The length of the cry matters. I especially value an extended session, which gives me time to become curious, to look in the mirror, to observe my physical sadness. A truly powerful cry can withstand even this scientific activity. You lurch toward the bathroom, head hunched over, tucked in, and then gather your nerve to lift your gaze toward the mirror, where you see your hiccoughing breath shake your shoulders, your nose like a lifelong drunk’s. It may interest you for a while to touch your swollen face, to peer into one bloodshot eye and another, but the beauty’s really in the movement, in watching your mouth try to swallow despair. It is not easy, after looking, to convince the crying you mean it no harm, but with quiet and with patience—you are Jane Goodall with the chimpanzees—the crying will slowly get used to you. It will return.

•••

To cry or not to cry is sometimes a choice, and no telling which is the better. Not true—if you are alone, or with only one other, cry. To cry with more people present, concludes the International Study of Adult Crying, can lead to a worsening mood, though that may depend on others’ reactions. You can be made to feel ashamed. Most frequently criers report others responding with compassion, or what the study categorizes as “comfort words, comfort arms, and understanding.” If you are alone, comfort arms are still available; you hold yourself together.

•••

It is fortunate to have a nose. Hard to feel you are too tragic a figure when the tears mix with snot. There is no glamour in honking.

•••

Once I was unexpectedly dumped in public. A campus parking lot one afternoon. I put all my crying into my mouth, felt it shake while I stalked to the car, inside which I let the crying move north to my eyes and south to my heaving gut. The car is a private crying area. If you see a person crying near a car, you may need to offer help. If you see a person crying inside a car, you know they are already held.

by Heather Christle, Bookforum | Read more:

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

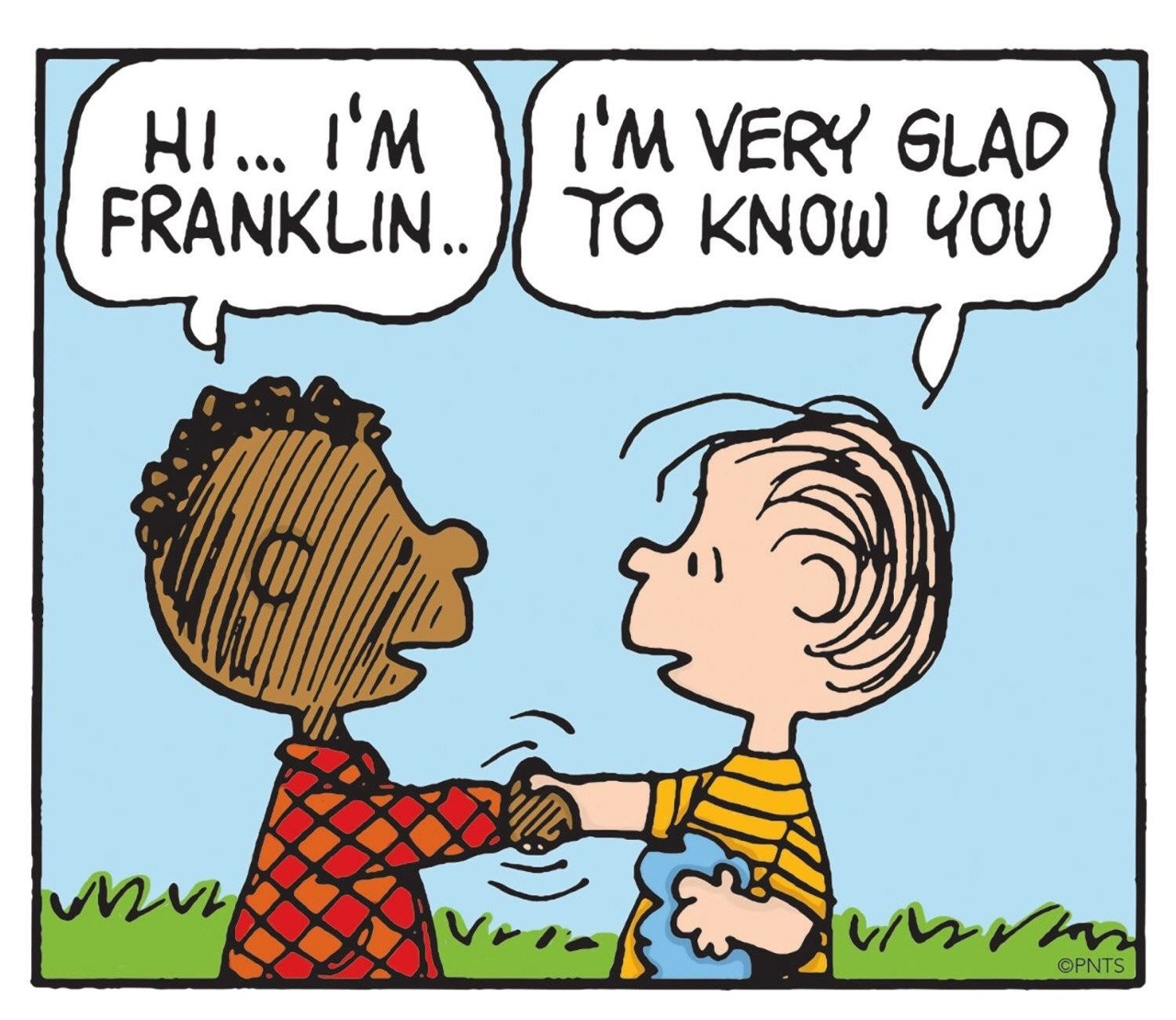

Very Glad to Know You

What they saw was Franklin Armstrong’s first appearance on the iconic comic strip “Peanuts.” Franklin would be 50 years old this year.

Franklin was “born” after a school teacher, Harriet Glickman, had written a letter to creator Charles M. Schulz after Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was shot to death outside his Memphis hotel room.

Glickman, who had kids of her own and having worked with kids, was especially aware of the power of comics among the young. “And my feeling at the time was that I realized that black kids and white kids never saw themselves [depicted] together in the classroom,” she would say.

She would write, “Since the death of Martin Luther King, ‘I’ve been asking myself what I can do to help change those conditions in our society which led to the assassination and which contribute to the vast sea of misunderstanding, hate, fear and violence.'”

Glickman asked Schulz if he could consider adding a black character to his popular comic strip, which she hoped would bring the country together and show people of color that they are not excluded from American society.

She had written to others as well, but the others feared it was too soon, that it may be costly to their careers, that the syndicate would drop them if they dared do something like that.

Charles Schulz did not have to respond to her letter, he could have just completely ignored it, and everyone would have forgotten about it. But, Schulz did take the time to respond, saying he was intrigued with the idea, but wasn’t sure whether it would be right, coming from him, he didn’t want to make matters worse, he felt that it may sound condescending to people of color.

Glickman did not give up, and continued communicating with Schulz, with Schulz surprisingly responding each time. She would even have black friends write to Schulz and explain to him what it would mean to them and gave him some suggestions on how to introduce such a character without offending anyone. This conversation would continue until one day, Schulz would tell Glickman to check her newspaper on July 31, 1968.

On that date, the cartoon, as created by Schulz, shows Charlie Brown meeting a new character, named Franklin. Other than his color, Franklin was just an ordinary kid who befriends and helps Charlie Brown. Franklin also mentions that his father was “over at Vietnam.” At the end of the series, which lasted three strips, Charlie invites Franklin to spend the night one day so they can continue their friendship.

Read more: via:

Always Be My Maybe ft. Keanu Reeves

[ed. "The only stars that matter are the one's you look at when you dream..."]

The Mister Rogers No One Saw

Up at the castle, in front of the cameras, the puppets were eagerly preparing for a festival. Dwarfed beneath high rows of stage lights, in front of painted trees, they bopped happily along the pretend stone wall. But there was a buzz kill: King Friday XIII, the mighty ruler in his bright purple cape, decreed that the festival would be a bass-violin festival.

“But you’re the only one who plays the bass violin,” one of the neighbors pointed out.

“Oh, so I am,” the king replied. “Well, it looks like I’ll have a very large audience.”

Fred Rogers was on his knees behind the castle, dressed all in black, working the puppets, his posture straight as a soldier’s, lips pursed tight as he voiced the king. There were cushions strewn on the floor and blocks of foam rubber taped to the parts of the castle where he tended to bonk his head. In one swift movement he crouched, slipped off the king, slid on another puppet. He shot his arm up, returned to his knees, but this time he slouched, his face softening as he voiced the meek and bashful Daniel Striped Tiger.

And so the neighbors scrambled about trying to figure out a way to be part of the festival. Stumped, and on the sly, they began to invent bass-violin acts they might contribute. One dressed up her accordion to look like a bass violin, another practiced a dance with one, another tried to turn herself into one by wearing a big fat bass-violin suit. Another, a goat, recited a bass-violin poem in goat language. (“Mehh.”)

And so the neighbors scrambled about trying to figure out a way to be part of the festival. Stumped, and on the sly, they began to invent bass-violin acts they might contribute. One dressed up her accordion to look like a bass violin, another practiced a dance with one, another tried to turn herself into one by wearing a big fat bass-violin suit. Another, a goat, recited a bass-violin poem in goat language. (“Mehh.”)

“If you didn’t know what was going on,” one of the guys on the crew said, “this could be a very weird situation.”

Was this O.K.? Would the king approve?

He did. In fact, he was delighted. It turned into a most rockin’ bass-violin festival, neighbors singing and twirling with pretend and real bass violins (including a puppet holding a bass-violin puppet), around balloons with little cardboard handles taped to them to look like bass violins, to rousing bass-violin/accordion polka tunes accompanying bass-violin-inspired goat poems.

I appreciated that. I worked for a different department in the building, at WQED in Pittsburgh, down the hall. They had microwave popcorn in the cafeteria. To get to the popcorn you had to walk by Studio A, and there was usually the blue castle parked outside it for storage. If the castle wasn’t there, you knew they were taping inside, and sometimes you heard music. It was fun to go in and watch, if only to take in the live music, usually jazz, and to marvel at the bizarro factor. (...)

Fred Rogers was a curious, lanky man, six feet tall and 143 pounds (exactly, he said, every day; he liked that each digit corresponded to the number of letters in the words “I love you”) and utterly devoid of pretense. He liked to pray, to play the piano, to swim and to write, and he somehow lived in a different world than I did. A hushed world of tiny things — the meager and the marginalized. A world of simple words and deceptively simple concepts, and a slowness that allowed for silence, focus and joy. We became friends for some 20 years, and I made lifelong friends with his wife, Joanne. I remember thinking that it seemed as if Fred had access to another realm, like the way pigeons have some special magnetic compass that helps them find home.

Fred died in 2003, somewhat quickly, of stomach cancer. He was 74. It was years after his death that he would, suddenly, go from a kind of lovable PBS novelty to an icon on the magnitude of the divine. It happened so fast that it was easy to gloss over his actual message. He gets reduced to a symbol. A conveyor of virtue! The god of kindness! Something like that, according to the memes.

“Just don’t make Fred into a saint.” That has become Joanne’s refrain. She’s 91 now, still a bundle of energy, lives alone in the same roomy apartment, in the university section of Pittsburgh, that she and Fred moved into after they raised their two boys. Mention her name to anyone around town who knows her, and you’ll very likely be rewarded with a fabulous grin. She’s funny. She laughs louder and bigger than just about anyone I know, to the point where it can go into a snort, which makes her go full-on guffaw. Throughout her 50-year marriage to Fred, she wasn’t the type to hang out on the set at WQED or attend production meetings. That was Fred’s thing. He had his career, and she had hers as a concert pianist. For decades she toured the country with her college classmate, Jeannine Morrison, as a piano duo; they didn’t retire the performance until 2008.

Joanne’s refrain has been adopted by people who spent their careers working with Fred in Studio A. “If you make him out to be a saint, nobody can get there,” said Hedda Sharapan, the person who worked with Fred the longest in various creative capacities over the years. “They’ll think he’s some otherworldly creature.”

“If you make him out to be a saint, people might not know how hard he worked,” Joanne said. Disciplined, focused, a perfectionist — an artist. That was the Fred she and the cast and crew knew. “I think people think of Fred as a child-development expert,” David Newell, the actor who played Mr. “Speedy Delivery” McFeely, told me recently. “As a moral example maybe. But as an artist? I don’t think they think of that.”

That was the Fred I came to know. Creating, the creative impulse and the creative process were our common interests. He wrote or co-wrote all the scripts for the program — all 33 years of it. He wrote the melodies. He wrote the lyrics. He structured a week of programming around a single theme, many of them difficult topics, like war, divorce or death.

by Jeanne Marie Laskas, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Jim Judkis

[ed. A wonderful essay.]

“But you’re the only one who plays the bass violin,” one of the neighbors pointed out.

“Oh, so I am,” the king replied. “Well, it looks like I’ll have a very large audience.”

Fred Rogers was on his knees behind the castle, dressed all in black, working the puppets, his posture straight as a soldier’s, lips pursed tight as he voiced the king. There were cushions strewn on the floor and blocks of foam rubber taped to the parts of the castle where he tended to bonk his head. In one swift movement he crouched, slipped off the king, slid on another puppet. He shot his arm up, returned to his knees, but this time he slouched, his face softening as he voiced the meek and bashful Daniel Striped Tiger.

And so the neighbors scrambled about trying to figure out a way to be part of the festival. Stumped, and on the sly, they began to invent bass-violin acts they might contribute. One dressed up her accordion to look like a bass violin, another practiced a dance with one, another tried to turn herself into one by wearing a big fat bass-violin suit. Another, a goat, recited a bass-violin poem in goat language. (“Mehh.”)

And so the neighbors scrambled about trying to figure out a way to be part of the festival. Stumped, and on the sly, they began to invent bass-violin acts they might contribute. One dressed up her accordion to look like a bass violin, another practiced a dance with one, another tried to turn herself into one by wearing a big fat bass-violin suit. Another, a goat, recited a bass-violin poem in goat language. (“Mehh.”)“If you didn’t know what was going on,” one of the guys on the crew said, “this could be a very weird situation.”

Was this O.K.? Would the king approve?

He did. In fact, he was delighted. It turned into a most rockin’ bass-violin festival, neighbors singing and twirling with pretend and real bass violins (including a puppet holding a bass-violin puppet), around balloons with little cardboard handles taped to them to look like bass violins, to rousing bass-violin/accordion polka tunes accompanying bass-violin-inspired goat poems.

I appreciated that. I worked for a different department in the building, at WQED in Pittsburgh, down the hall. They had microwave popcorn in the cafeteria. To get to the popcorn you had to walk by Studio A, and there was usually the blue castle parked outside it for storage. If the castle wasn’t there, you knew they were taping inside, and sometimes you heard music. It was fun to go in and watch, if only to take in the live music, usually jazz, and to marvel at the bizarro factor. (...)

Fred Rogers was a curious, lanky man, six feet tall and 143 pounds (exactly, he said, every day; he liked that each digit corresponded to the number of letters in the words “I love you”) and utterly devoid of pretense. He liked to pray, to play the piano, to swim and to write, and he somehow lived in a different world than I did. A hushed world of tiny things — the meager and the marginalized. A world of simple words and deceptively simple concepts, and a slowness that allowed for silence, focus and joy. We became friends for some 20 years, and I made lifelong friends with his wife, Joanne. I remember thinking that it seemed as if Fred had access to another realm, like the way pigeons have some special magnetic compass that helps them find home.

Fred died in 2003, somewhat quickly, of stomach cancer. He was 74. It was years after his death that he would, suddenly, go from a kind of lovable PBS novelty to an icon on the magnitude of the divine. It happened so fast that it was easy to gloss over his actual message. He gets reduced to a symbol. A conveyor of virtue! The god of kindness! Something like that, according to the memes.

“Just don’t make Fred into a saint.” That has become Joanne’s refrain. She’s 91 now, still a bundle of energy, lives alone in the same roomy apartment, in the university section of Pittsburgh, that she and Fred moved into after they raised their two boys. Mention her name to anyone around town who knows her, and you’ll very likely be rewarded with a fabulous grin. She’s funny. She laughs louder and bigger than just about anyone I know, to the point where it can go into a snort, which makes her go full-on guffaw. Throughout her 50-year marriage to Fred, she wasn’t the type to hang out on the set at WQED or attend production meetings. That was Fred’s thing. He had his career, and she had hers as a concert pianist. For decades she toured the country with her college classmate, Jeannine Morrison, as a piano duo; they didn’t retire the performance until 2008.

Joanne’s refrain has been adopted by people who spent their careers working with Fred in Studio A. “If you make him out to be a saint, nobody can get there,” said Hedda Sharapan, the person who worked with Fred the longest in various creative capacities over the years. “They’ll think he’s some otherworldly creature.”

“If you make him out to be a saint, people might not know how hard he worked,” Joanne said. Disciplined, focused, a perfectionist — an artist. That was the Fred she and the cast and crew knew. “I think people think of Fred as a child-development expert,” David Newell, the actor who played Mr. “Speedy Delivery” McFeely, told me recently. “As a moral example maybe. But as an artist? I don’t think they think of that.”

That was the Fred I came to know. Creating, the creative impulse and the creative process were our common interests. He wrote or co-wrote all the scripts for the program — all 33 years of it. He wrote the melodies. He wrote the lyrics. He structured a week of programming around a single theme, many of them difficult topics, like war, divorce or death.

by Jeanne Marie Laskas, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Jim Judkis

[ed. A wonderful essay.]

Labels:

Celebrities,

Culture,

Education,

Media,

Psychology,

Relationships

Monday, November 18, 2019

The Homeownership Obsession

While academics and journalists questioned the conventional wisdom, the dominant idea was that buying a house was a solid investment plan, a responsible decision that required commitment (30 years of mortgage payments) and a sturdy sense of hope. American culture has always been oriented toward the future rather than reckoning with the past, and homeownership, particularly in the suburbs, was no different. Yet this wasn’t always part of the American dream. The American dream was originally about “rags to riches, coming from nothing and ending up a robber baron,” says Rachel Heiman, associate professor of anthropology at the New School. It was about money. It was only during the McCarthy era that homeownership became a crucial part of the story.

“People rarely realize that the desire to be a homeowner isn’t a purely natural desire, though we tend to think about it as inherent,” Heiman says. When we think about the McCarthy hearings, we often remember the Hollywood aspect—the glamorous stars persecuted for their supposed leftist leanings. But before McCarthy gave his famous anti-communist speech in Wheeling, West Virginia, the senator had focused much of his career on opposing public housing and protecting corporate interests. Since the post-World War II period, the government had been providing housing to veterans and their families. “They did an extraordinary job of building affordable housing on a mass scale during the war,” explains Heiman. In the 1940s, McCarthy and other right-wing politicians became concerned that the housing projects had gone too far—McCarthy even called public housing “breeding ground[s] for communists.” In the late 1940s, he sided with William Levitt (and other private manufacturers) in their fight against public housing projects. Levitt was promoting his cookie-cutter housing communities, which McCarthy believed were more in line with America’s capitalist economic structure and ideals. (“No man who owns his own house and lot can be a communist. He has too much to do,” Levitt once famously said.) As the Cold War wore on, this sentiment grew, particularly among members of the Republican Party. From 1950 onward, Heiman says, “homeownership was packaged and sold.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19350120/Curbed_Cult_Spot_1.jpg) Suddenly, it became important for the U.S. government to shift its focus from providing housing for those in need to providing mortgage assistance. “The government helped people, but only white people, to get into the suburbs,” Heiman says. This was the legacy of redlining, a New Deal-era process of color-coding neighborhoods based on income, labeling some as good investments and others as “risky.” The government was more likely to help people refinance their homes or purchase homes in areas they deemed secure, which prevented generations of African Americans (who lived disproportionately in “risky,” i.e., low-income, areas) from being able to lift themselves out of poverty. Although redlining was outlawed in 1968 by the Fair Housing Act, the effects echoed through American culture for decades and continue to do so to this day. Popular culture also helped reinforce suburban segregation. Magazines and newspapers ran advertisements for Levittown and other similar housing developments, which nearly always showed white couples or children engaging in wholesome activities (one showed a young couple, man in uniform, drawing their dream house in the sand, while another showed a young white child jumping into a pool). Television advertisements were no better. The message was clear enough: The suburbs—and the American dream, by extension—weren’t for everyone.

Suddenly, it became important for the U.S. government to shift its focus from providing housing for those in need to providing mortgage assistance. “The government helped people, but only white people, to get into the suburbs,” Heiman says. This was the legacy of redlining, a New Deal-era process of color-coding neighborhoods based on income, labeling some as good investments and others as “risky.” The government was more likely to help people refinance their homes or purchase homes in areas they deemed secure, which prevented generations of African Americans (who lived disproportionately in “risky,” i.e., low-income, areas) from being able to lift themselves out of poverty. Although redlining was outlawed in 1968 by the Fair Housing Act, the effects echoed through American culture for decades and continue to do so to this day. Popular culture also helped reinforce suburban segregation. Magazines and newspapers ran advertisements for Levittown and other similar housing developments, which nearly always showed white couples or children engaging in wholesome activities (one showed a young couple, man in uniform, drawing their dream house in the sand, while another showed a young white child jumping into a pool). Television advertisements were no better. The message was clear enough: The suburbs—and the American dream, by extension—weren’t for everyone.As the old adage goes, a crucial part of purchasing real estate is recognizing the significance of “location, location, location,” and from the 1950s onward, that location was almost always the suburbs. But like the idea of homeownership in general, the concept of owning a suburban home was fed to Americans by people in power. Suburbia has always been good for industry. Big houses required big appliances and used lots of carbon, creating a “hydrocarbon middle-class family” that was buoyed by three industries: coal, steel, and automaking. “Suturing the growing metropolitan regions together were, of course, cars, which made the postwar American suburb possible,” writes Robert O. Self in his 2014 Salon article “Cataclysm in suburbia: The dark, twisted history of America’s oil-addicted middle class.” Self points to the 1956 National Interstate and Defense Highways Act, which provided 90 cents for every dime the states invested in interstate highways, “effectively making sprawl as much a creature of government as of the market.” (...)

I’ve spoken with dozens of millennials about the topic of homebuying—both as research for my work, and out of curiosity. I am a millennial who owns a house; I’m also a 32-year-old who watched my parents lose control of their finances in the market crash. For me, like many other adults my age, the idea of owning a house is both a dream and a nightmare.

I visited my first open house during a sunny Sunday in June. It was a quintessential spring day in Portland, Maine. Lilacs and rhododendrons were blooming, the grass was finally bright green, and the maple and oak leaves had fully unfurled. It was the ideal backdrop for viewing a three-bedroom brick cape on the outskirts of the city, especially since one of the home’s selling points is the back patio and garden, hedged in by boxwoods, made private by small trees and big fences.

This is where I found Brody Van Geem and Brooke Brown-Saracino, 30-something transplants from California who moved to Maine three years ago after being priced out of the West Coast. Portland, they thought, would be an affordable city with a “slower pace of life.” Brown-Saracino said she “couldn’t imagine a future” in California, “given how expensive it is.” When we spoke, Brown-Saracino was cradling their 5-week-old newborn. They already owned a condo downtown (on the “peninsula,” as we call Portland’s densest and most expensive area), but were looking to buy somewhere where they could be closer to nature and have a bit more room to grow their family.

When they bought their condo, this millennial couple wasn’t thinking about acquiring their “dream home.” They knew that was out of the question. “We thought of it as a more financially viable choice than renting,” said Brown-Saracino. “It felt like a very practical and financially driven decision.” She had to “reconcile” this mindset with her “lifetime notion” that the first house she bought would be a home. A place where she would raise children and live until she grew old. Or, at least, until the kids were old enough to leave for college. “This is the narrative that I think was fed to past generations—and is still a component of my emotional relationship to homeownership—but most of me had shifted to a much more practical, financial narrative,” she said. “I think this is probably driven by how expensive homeownership is today.”

University of Michigan professor Karyn Lacy, who studies black American upper-middle-class and “elite” millennials, has noticed a widespread shift in how people view their first real estate purchase. Baby boomers, she says, “went to high school, college, got married right after, and bought homes as a couple.” Now, millennials are doing everything later. They’re buying houses as single people rather than waiting to get married and have their first kids. The properties they purchase aren’t “homes,” explains Lacy. “They’re places to live without paying rent.”

This is something upper-class adults learn from their parents. “The kids that I study understand that this is a way to accumulate wealth without having to do much else,” says Lacy. “You buy it, you live in it, you go about your daily life, and in five years you’ll have a nice nest egg to move up from your starter house to your dream home.” Kids who grow up in lower-income families don’t necessarily have that same ideal instilled in them.

The next open house I visited was much quieter—it was also more expensive. It crossed the half-million-dollar mark, a divide that seems to separate properties that attract millennial buyers from properties that attract a primarily boomer crowd. In the two hours I spent talking with realtor Jody Ryan, I didn’t meet any prospective homeowners under the age of 50. Millennials, she says, don’t really want a house this big (2,700 square feet) or with so many expensive fixtures and fittings. “A lot of them are buying little ranches,” she said as we waited for another buyer to wander in. “They want splits and ranches or houses that are good for easy living.” (The other trend Ryan noticed was that millennials often want houses with big tubs for their pets, so they can “stick ’em in and spray them. They’ve got lots of pets.”)

by Katy Kelleher, Curbed | Read more:

Image: Kelly Abeln

Not Even Wrong

"Not even wrong" describes an argument or explanation that purports to be scientific but is based on invalid reasoning or speculative premises that can neither be proven correct nor falsified and thus cannot be discussed in a rigorous and scientific sense. For a meaningful discussion on whether a certain statement is true or false, the statement must satisfy the criterion of falsifiability, the inherent possibility for the statement to be tested and found false. In this sense, the phrase "not even wrong" is synonymous to "nonfalsifiable".

The phrase is generally attributed to theoretical physicist Wolfgang Pauli, who was known for his colorful objections to incorrect or careless thinking. Rudolf Peierls documents an instance in which "a friend showed Pauli the paper of a young physicist which he suspected was not of great value but on which he wanted Pauli's views. Pauli remarked sadly, 'It is not even wrong'." This is also often quoted as "That is not only not right; it is not even wrong", or in Pauli's native German, "Das ist nicht nur nicht richtig; es ist nicht einmal falsch!". Peierls remarks that quite a few apocryphal stories of this kind have been circulated and mentions that he listed only the ones personally vouched for by him. He also quotes another example when Pauli replied to Lev Landau, "What you said was so confused that one could not tell whether it was nonsense or not."

The phrase is often used to describe pseudoscience or bad science.

The phrase is generally attributed to theoretical physicist Wolfgang Pauli, who was known for his colorful objections to incorrect or careless thinking. Rudolf Peierls documents an instance in which "a friend showed Pauli the paper of a young physicist which he suspected was not of great value but on which he wanted Pauli's views. Pauli remarked sadly, 'It is not even wrong'." This is also often quoted as "That is not only not right; it is not even wrong", or in Pauli's native German, "Das ist nicht nur nicht richtig; es ist nicht einmal falsch!". Peierls remarks that quite a few apocryphal stories of this kind have been circulated and mentions that he listed only the ones personally vouched for by him. He also quotes another example when Pauli replied to Lev Landau, "What you said was so confused that one could not tell whether it was nonsense or not."

The phrase is often used to describe pseudoscience or bad science.

by Wikipedia | Read more:

[ed. See also: Briefing: Not even wrong (Guardian).]Getting a Handle on Self-Harm

“I had this Popsicle stick and carved it into sharp point and scratched myself,” Joan, a high school student in New York City said recently; she asked that her last name be omitted for privacy. “I’m not even sure where the idea came from. I just knew it was something people did. I remember crying a lot and thinking, Why did I just do that? I was kind of scared of myself.”

She felt relief as the swarm of distress dissolved, and she began to cut herself regularly, at first with a knife, then razor blades, cutting her wrists, forearms and eventually much of her body. “I would do it for five to 15 minutes, and afterward I didn’t have that terrible feeling. I could go on with my day.”

Self-injury, particularly among adolescent girls, has become so prevalent so quickly that scientists and therapists are struggling to catch up. About 1 in 5 adolescents report having harmed themselves to soothe emotional pain at least once, according to a review of three dozen surveys in nearly a dozen countries, including the United States, Canada and Britain. Habitual self harm, over time, is a predictor for higher suicide risk in many individuals, studies suggest.

Self-injury, particularly among adolescent girls, has become so prevalent so quickly that scientists and therapists are struggling to catch up. About 1 in 5 adolescents report having harmed themselves to soothe emotional pain at least once, according to a review of three dozen surveys in nearly a dozen countries, including the United States, Canada and Britain. Habitual self harm, over time, is a predictor for higher suicide risk in many individuals, studies suggest.But there are very few dedicated research centers for self-harm, and even fewer clinics specializing in treatment. When youngsters who injure themselves seek help, they are often met with alarm, misunderstanding and overreaction. The apparent epidemic levels of the behavior have exposed a structural weakness of psychiatric care: Because self-injury is considered a “symptom,” and not a stand-alone diagnosis like depression, the testing of treatments has been haphazard and therapists have little evidence to draw on.

In the past few years, psychiatric researchers have begun to knit together the motives, underlying biology and social triggers of self-harm. The story thus far gives parents — tens of million worldwide — some insight into what is at work when they see a child with scars or burns. And it allows for the evaluation of tailored treatments: In one newly published trial, researchers in New York found that self-injury can be reduced with a specialized form of talk therapy that was invented to treat what’s known as borderline personality disorder.

“It used to be that this kind of behavior was confined to the very severely impaired, people with histories of sexual abuse, with major body alienation,” said Barent Walsh, a psychologist who was one of the first therapists to focus on treating self-injury, at The Bridge program in Marlborough, Mass., now a part of Open Sky Community Services. “Then, suddenly, it morphed into the general population, to the point where it was affecting successful kids with money. That’s when the research funding started to flow, and we’ve gotten a better handle on what’s happening.”

Joan was 13 when the cutting began. Now 16, she had greatly curtailed this routine in the past few months, she said: “But I still do it, like, every week or so.”

The most common misperception about self-injury is that it is a suicide attempt: A parent walks in on an adolescent cutting herself or himself, and the sight of blood is blinding. “A lot of people think that, but in reality, you cut for different reasons,” said Blue, 16, another high school student in the New York area, who asked that her last name be omitted. “Like, it’s the only way you know to deal with intense insecurities, or anger at yourself. Or you’re so numb as a result of depression, you can’t feel anything — and this is one thing you can feel.”

Whether this method of self-soothing is an epidemic of the social media age is still a matter of scientific debate. No surveys asking about self-harm were conducted before the mid-1980s, in part because few researchers thought to ask. (...)

This on-again, off-again pattern becomes, for about 20 percent of people who engage in it, a full-blown addiction, as powerful as an opiate habit. “Something about it was so grounding, and it was always there for me,” said Nancy Dupill, 32, who cut herself regularly for more than a decade before winding down the habit, in therapy; she now works as a peer specialist for adolescents in central Massachusetts. “I got to the point where I cut myself a lot, and when I came out of it, I couldn’t remember things that happened, like what set it off in the first place.”

People who become dependent on self-harm often come to treasure it as their one reliable comfort, therapists say. Images of blood, burns, cuts and scarring may become, paradoxically, consoling. In isolation, amid emotional turbulence, self-injury is a secret friend, one that can be summoned anytime, without permission or payment. “Unlike emotional or social pain, it’s possible to control physical pain” and its soothing effect, said Joseph Franklin, a psychologist at Florida State University.

by Benedict Carey, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Keith Negley

A New Type of Scam: Business Email Compromise

The secret to comedy, according to the old joke, is timing. The same is true of cybercrime.

Mark learned this the hard way in 2017. He runs a real estate company in Seattle and asked us not to include his last name because of the possible repercussions for his business.

"The idea that someone was effectively able to dupe you ... is embarrassing," he says. "We're still kind of scratching our head over how it happened."

"The idea that someone was effectively able to dupe you ... is embarrassing," he says. "We're still kind of scratching our head over how it happened."It started when someone hacked into his email conversation with a business partner. But the hackers didn't take over the email accounts. Instead, they lurked, monitoring the conversation and waiting for an opportunity.

When Mark and his partner mentioned a $50,000 disbursement owed to the partner, the scammers made their move.

"They were able to insert their own wiring instructions," he says. Pretending to be Mark's partner, they asked him to send the money to a bank account they controlled.

"The cadence and the timing and the email was so normal that it wasn't suspicious at all. It was just like we were continuing to have a conversation, but I just wasn't having it with the person I thought I was," Mark says.

He didn't realize what had happened until his partner said he'd never gotten the money. "Oh, it was just a cold sweat," he says.

By the time they alerted the bank, the $50,000 was long gone, transferred overseas.

It turned out Mark was on the vanguard of a growing wave of something called "business email compromise," or BEC. It's a category of scam that uses phony emails to trick employees at companies to wire money to the wrong accounts. The FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center says reported BEC amounted to more than $1.2 billion in 2018, nearly triple the figure in 2016. (...)

"What we've seen in 2019 is that the wave that's breaking is primarily focused around social engineering," says Patrick Peterson, CEO of Agari, a company that specializes in protecting corporate email systems. "Social engineering" is hacker-speak for scams that rely less on technical tricks and more on taking advantage of human vulnerabilities.

"It's not so much having the most sophisticated, evil technology. It's using our own trust and desire to communicate with others against us," Peterson says.

In the past, scammers have pretended to be business partners and CEOs, urging employees to send money for an urgent matter. But lately there has been a trend toward what Agari calls "vendor email compromise" — scammers pretending to be part of a company's supply chain.

by Martin Kaste, NPR | Read more:

Image: Deborah Lee

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)