[ed. This just came out in paperback and I can't wait to read it. The reviews I've read so far say this could be one of the best non-fiction books of 2011]

by Laura Miller

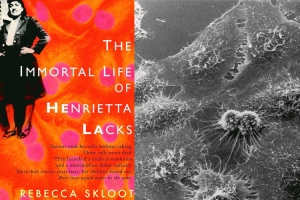

The scientific story told in Rebecca Skloot's "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" is marvel enough: Lacks died in 1951, but also lives on in the form of cells, taken from a single biopsy, that have proven easier to grow in a lab than any other human tissue ever sampled. So easy, in fact, that one scientist has estimated that if you could collect all of the cells descended from that first sample on a scale, the total would weigh 50 million metric tons. Lacks' famous cell line, known as HeLa, has played a key role in the development of cures and treatments for polio, AIDS, infertility and cancer, as well as research into cloning, gene mapping and radiation.

There's a run-of-the-mill "The Cells That Changed the World" book in that premise, and one with a better claim to credibility than most of the "Changed the World" titles that have flooded bookstores since Dava Sobel's "Longitude" became a surprise bestseller 14 years ago. But "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" is far from run-of-the-mill -- it's indelible. Skloot (whom -- full disclosure -- I know slightly) spent a decade tracking down Lacks' surviving family and winning over their much-abused trust, a process that becomes part of the story she tells. Actually, it often takes over the story entirely. Just as the DNA in a cell's nucleus contains the blueprint for an entire organism, so does the story of Henrietta Lacks hold within it the history of medicine and race in America, a history combining equal parts of shame and wonder.

Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman born and raised in rural Virginia, was treated for the cervical cancer that killed her in Baltimore's Johns Hopkins Hospital. A sample of her cancer cells taken during an early examination was handed over to a Hopkins researcher, George Gey, who probably never met Lacks herself. Unlike the vast majority of human cells, which almost always die soon after being removed from the body, Lacks' turned out to be astonishingly robust and easy to culture. They contain an enzyme that prevents them from automatically degenerating like normal cells, rendering them immortal, capable of dividing and multiplying seemingly forever. HeLa has provided countless experimenters with the once-rare raw materials needed to test drugs and procedures that have saved lives and transformed medicine.

But Lacks never knew her cells had been taken by Gey or why. Her family, who struggled to survive through a series of hardships that make "The Color Purple" look tame by comparison, occasionally heard from Hopkins or from journalists captivated by the HeLa story, but they had difficulty understanding what little information they were given. Then, in the '60s, a scientist discovered that most of the other cell lines being cultivated throughout the world had been contaminated by HeLa cells, and had probably been taken over by them. Hopkins researchers tracked down the Lackses to get the blood samples they needed to detect that contamination; the family thought they were being tested for the terrifying disease that had killed Henrietta. They believed that "Henrietta" had been shot into space, blown up with nuclear bombs and cloned. They worried that she might somehow be suffering through these experiences. And, eventually, they were enraged to learn that companies were making money selling vials of her cells while her children couldn't even afford medical insurance.

Read more:

The scientific story told in Rebecca Skloot's "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" is marvel enough: Lacks died in 1951, but also lives on in the form of cells, taken from a single biopsy, that have proven easier to grow in a lab than any other human tissue ever sampled. So easy, in fact, that one scientist has estimated that if you could collect all of the cells descended from that first sample on a scale, the total would weigh 50 million metric tons. Lacks' famous cell line, known as HeLa, has played a key role in the development of cures and treatments for polio, AIDS, infertility and cancer, as well as research into cloning, gene mapping and radiation.

There's a run-of-the-mill "The Cells That Changed the World" book in that premise, and one with a better claim to credibility than most of the "Changed the World" titles that have flooded bookstores since Dava Sobel's "Longitude" became a surprise bestseller 14 years ago. But "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks" is far from run-of-the-mill -- it's indelible. Skloot (whom -- full disclosure -- I know slightly) spent a decade tracking down Lacks' surviving family and winning over their much-abused trust, a process that becomes part of the story she tells. Actually, it often takes over the story entirely. Just as the DNA in a cell's nucleus contains the blueprint for an entire organism, so does the story of Henrietta Lacks hold within it the history of medicine and race in America, a history combining equal parts of shame and wonder.

Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman born and raised in rural Virginia, was treated for the cervical cancer that killed her in Baltimore's Johns Hopkins Hospital. A sample of her cancer cells taken during an early examination was handed over to a Hopkins researcher, George Gey, who probably never met Lacks herself. Unlike the vast majority of human cells, which almost always die soon after being removed from the body, Lacks' turned out to be astonishingly robust and easy to culture. They contain an enzyme that prevents them from automatically degenerating like normal cells, rendering them immortal, capable of dividing and multiplying seemingly forever. HeLa has provided countless experimenters with the once-rare raw materials needed to test drugs and procedures that have saved lives and transformed medicine.

But Lacks never knew her cells had been taken by Gey or why. Her family, who struggled to survive through a series of hardships that make "The Color Purple" look tame by comparison, occasionally heard from Hopkins or from journalists captivated by the HeLa story, but they had difficulty understanding what little information they were given. Then, in the '60s, a scientist discovered that most of the other cell lines being cultivated throughout the world had been contaminated by HeLa cells, and had probably been taken over by them. Hopkins researchers tracked down the Lackses to get the blood samples they needed to detect that contamination; the family thought they were being tested for the terrifying disease that had killed Henrietta. They believed that "Henrietta" had been shot into space, blown up with nuclear bombs and cloned. They worried that she might somehow be suffering through these experiences. And, eventually, they were enraged to learn that companies were making money selling vials of her cells while her children couldn't even afford medical insurance.

Read more: