The life of the humble biomedical postdoctoral researcher was never easy: toiling in obscurity in a low-paying scientific apprenticeship that can stretch more than a decade. The long hours were worth it for the expected reward — the chance to launch an independent laboratory and do science that could expand human understanding of biology and disease.

But in recent years, the postdoc position has become less a stepping stone and more of a holding tank. Some of the smartest people in Boston are caught up in an all-but-invisible crisis, mired in a biomedical underclass as federal funding for research has leveled off, leaving the supply of well-trained scientists outstripping demand.

But in recent years, the postdoc position has become less a stepping stone and more of a holding tank. Some of the smartest people in Boston are caught up in an all-but-invisible crisis, mired in a biomedical underclass as federal funding for research has leveled off, leaving the supply of well-trained scientists outstripping demand.

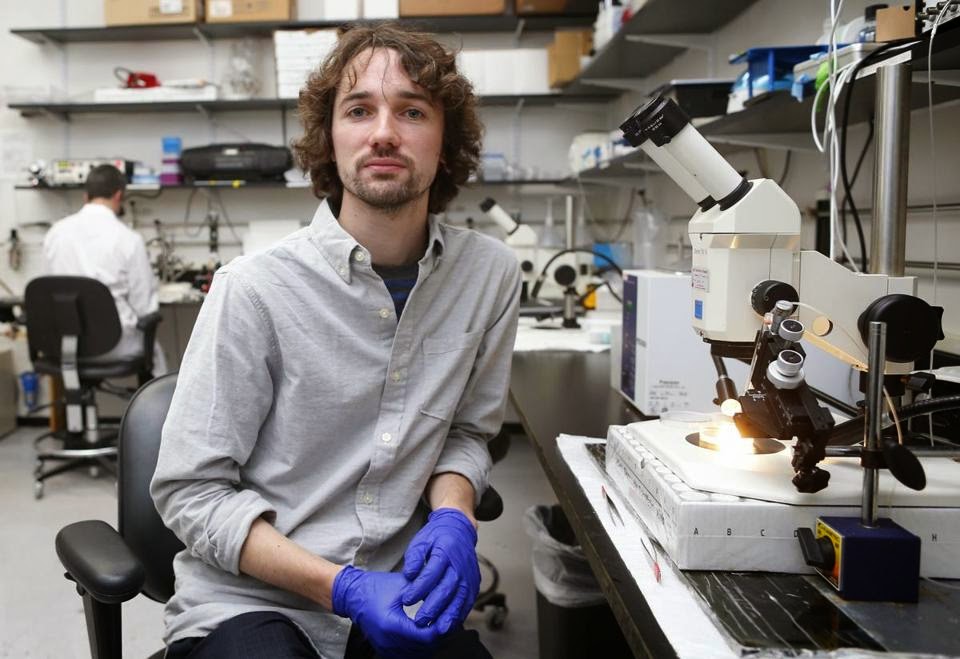

“It’s sunk in that it’s by no means guaranteed — for anyone, really — that an academic position is possible,” said Gary McDowell, 29, a biologist doing his second postdoc at Tufts University who hopes to set up his own lab in a few years. “There’s this huge labor force here to do the bench work, the grunt work of science. But then there’s nowhere for them to go; this massive pool of postdocs that accumulates and keeps growing.”

Postdocs fill an essential, but little-known niche in the scientific pipeline. After spending 6 to 7 years on average earning a PhD, they invest more years of training in a senior scientist’s laboratory as the final precursor to starting labs where they can explore their own scientific ideas.

In the Boston area, where more than 8,000 postdocs — largely in the biosciences — are estimated to work, tough job prospects are more than just an issue of academic interest. Postdocs are a critical part of the scientific landscape that in many ways distinguishes the region — they are both future leaders and the workers who carry out experiments crucial for science to advance.

The plight of postdocs has become a point of national discussion among senior scientists, as their struggles have come to be seen as symptoms of broader problems plaguing biomedical research. After years of rapid growth, federal funding abruptly leveled off and even contracted over the last decade, leaving a glut of postdocs vying for a limited number of faculty jobs. Paradoxically, as they’ve gotten stuck, the pursuit of research breakthroughs has also become reliant on them as a cheap source of labor for senior scientists.

Biomedical research training traditionally has followed a well-worn path. After college, people who want to pursue an advanced degree enroll in graduate school. The vast majority of biology graduate students then go on to do one or more postdoc positions, where they continue their training, often well into their 30s. (...)

The problem is that any researcher running a lab today is training far more people than there will ever be labs to run. Often these supremely well-educated trainees are simply cheap laborers, not learning skills for the careers where they are more likely to find jobs — teaching, industry, government or nonprofit jobs, or consulting.

This wasn’t such an issue decades ago, but universities have expanded the number of PhD students they train — there were about 30,000 biomedical graduate students in 1979 and 56,800 in 2009. That has had the effect of flooding the system with trainees and drawing out the training period.

In 1970, scientists typically received their first major federal funding when they were 34. In 2011, those lucky enough to get a coveted tenure-track faculty position and run their own labs, at an average age of 37, don’t get the equivalent grant until nearly a decade later, at age 42.

Facing these stark statistics, postdocs are taking matters into their own hands. They organized a Future of Research conference in Boston last week that they hoped would give voice to their frustrations and hopes and help shape change.

“How can we, as the next generation, run the system?” said Kristin Krukenberg, 34, a lead organizer of the conference and a biologist in her sixth year as a postdoc at Harvard Medical School after six years in graduate school. Krukenberg plans to apply for faculty positions this year, and said that as she has neared the end of her long years of training, she has begun to think deeply about her future responsibilities to the people in her lab.

“Some of the models we see don’t seem tenable in the long run,” Krukenberg said.

by Carolyn Y. Johnson, Boston Globe | Read more:

Image: Jessica Rinaldi

But in recent years, the postdoc position has become less a stepping stone and more of a holding tank. Some of the smartest people in Boston are caught up in an all-but-invisible crisis, mired in a biomedical underclass as federal funding for research has leveled off, leaving the supply of well-trained scientists outstripping demand.

But in recent years, the postdoc position has become less a stepping stone and more of a holding tank. Some of the smartest people in Boston are caught up in an all-but-invisible crisis, mired in a biomedical underclass as federal funding for research has leveled off, leaving the supply of well-trained scientists outstripping demand.“It’s sunk in that it’s by no means guaranteed — for anyone, really — that an academic position is possible,” said Gary McDowell, 29, a biologist doing his second postdoc at Tufts University who hopes to set up his own lab in a few years. “There’s this huge labor force here to do the bench work, the grunt work of science. But then there’s nowhere for them to go; this massive pool of postdocs that accumulates and keeps growing.”

Postdocs fill an essential, but little-known niche in the scientific pipeline. After spending 6 to 7 years on average earning a PhD, they invest more years of training in a senior scientist’s laboratory as the final precursor to starting labs where they can explore their own scientific ideas.

In the Boston area, where more than 8,000 postdocs — largely in the biosciences — are estimated to work, tough job prospects are more than just an issue of academic interest. Postdocs are a critical part of the scientific landscape that in many ways distinguishes the region — they are both future leaders and the workers who carry out experiments crucial for science to advance.

The plight of postdocs has become a point of national discussion among senior scientists, as their struggles have come to be seen as symptoms of broader problems plaguing biomedical research. After years of rapid growth, federal funding abruptly leveled off and even contracted over the last decade, leaving a glut of postdocs vying for a limited number of faculty jobs. Paradoxically, as they’ve gotten stuck, the pursuit of research breakthroughs has also become reliant on them as a cheap source of labor for senior scientists.

Biomedical research training traditionally has followed a well-worn path. After college, people who want to pursue an advanced degree enroll in graduate school. The vast majority of biology graduate students then go on to do one or more postdoc positions, where they continue their training, often well into their 30s. (...)

The problem is that any researcher running a lab today is training far more people than there will ever be labs to run. Often these supremely well-educated trainees are simply cheap laborers, not learning skills for the careers where they are more likely to find jobs — teaching, industry, government or nonprofit jobs, or consulting.

This wasn’t such an issue decades ago, but universities have expanded the number of PhD students they train — there were about 30,000 biomedical graduate students in 1979 and 56,800 in 2009. That has had the effect of flooding the system with trainees and drawing out the training period.

In 1970, scientists typically received their first major federal funding when they were 34. In 2011, those lucky enough to get a coveted tenure-track faculty position and run their own labs, at an average age of 37, don’t get the equivalent grant until nearly a decade later, at age 42.

Facing these stark statistics, postdocs are taking matters into their own hands. They organized a Future of Research conference in Boston last week that they hoped would give voice to their frustrations and hopes and help shape change.

“How can we, as the next generation, run the system?” said Kristin Krukenberg, 34, a lead organizer of the conference and a biologist in her sixth year as a postdoc at Harvard Medical School after six years in graduate school. Krukenberg plans to apply for faculty positions this year, and said that as she has neared the end of her long years of training, she has begun to think deeply about her future responsibilities to the people in her lab.

“Some of the models we see don’t seem tenable in the long run,” Krukenberg said.

by Carolyn Y. Johnson, Boston Globe | Read more:

Image: Jessica Rinaldi