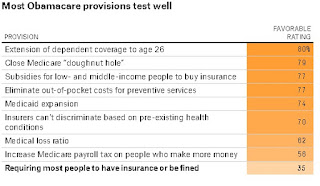

On the campaign trail, Donald Trump was clear that his priority for health care would be to repeal Obamacare. But after meeting with President Obama this week, he took a softer tone in an interview with The Wall Street Journal, saying that he’s looking into preserving some aspects of the law. Specifically, he expressed interest in two of the law’s most popular provisions: not allowing insurers to discriminate among buyers based on pre-existing health conditions and allowing young adults to stay on their parents’ health plans up to age 26. That still leaves a lot of unanswered questions about what he plans to do with the Affordable Care Act. (...)

Assuming that a reconciliation bill did pass, however, piecemeal changes would likely cause a lot of instability. The law is built on interlocking provisions; removing one puts pressure on others. That’s what happened when the Supreme Court made the Medicaid expansion optional for states, leaving 2.5 million people in states that chose not to expand in what has been called the Medicaid gap: too poor to be eligible for the marketplace subsidies but ineligible for Medicaid. Leaving in place the mandate for insurance companies to cover people with pre-existing conditions, as Trump said he’s considering, while getting rid of either the individual mandate — the requirement that people get insured — or the subsidies that motivate low-income healthy people to join the insurance rolls could also create instability in the insurance market. Without the necessary mix of healthy people in a plan to offset the costs of insuring people with pre-existing conditions, premiums rise, becoming unaffordable for everyone.

An estimated 22 million people would lose their insurance if Congress and Trump implemented the changes outlined in the most recent reconciliation bill. Even if Trump tries to hang onto the provisions he mentioned after meeting with Obama, it’s unclear what he might do to keep all those Americans insured. Looking at his campaign stump speeches, and proposed legislation from other Republicans, we can make some educated guesses about what might happen. (...)

Trump has said he wants to dismantle several key elements of the law, chief among them the individual mandate. He’s also said he’d like to use “block grants” that would provide a fixed sum, with fewer federal regulations, to states to fund Medicaid. It’s an idea that also features in House Speaker Paul Ryan’s health care proposal. That’s different from Medicaid expansion under the ACA, which requires that states cover everyone below 138 percent of the federal poverty line. It’s not clear how many of the millions of people who currently have Medicaid coverage under the ACA expansion would remain eligible for government assistance.

The individual mandate is a little more complicated. At one point, it was seen along most of the political spectrum as a promising way to reduce the number of uninsured people in the United States; requiring healthy people to sign up for coverage was supposed to ensure that premiums were affordable. The idea was originally floated by the conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation and was first brought to Congress by Republicans in the 1990s. The mandate has since become one of the most despised aspects of the law.

But there isn’t a clear policy proposal with bipartisan support for how to get more healthy people into the insurance market in the absence of an individual mandate and insurance subsidies. Trump has proposed creating high-risk pool insurance programs, essentially plans that people with pre-existing conditions can buy into. These types of plans existed in many states before the passage of the ACA and by design are not self-sustaining because members use significantly more health care than they can afford. That means they require significant federal dollars ($25 billion in the case of a plan from Ryan), which is one of the many reasons high-risk pools are divisive among Republican lawmakers.

Assuming that a reconciliation bill did pass, however, piecemeal changes would likely cause a lot of instability. The law is built on interlocking provisions; removing one puts pressure on others. That’s what happened when the Supreme Court made the Medicaid expansion optional for states, leaving 2.5 million people in states that chose not to expand in what has been called the Medicaid gap: too poor to be eligible for the marketplace subsidies but ineligible for Medicaid. Leaving in place the mandate for insurance companies to cover people with pre-existing conditions, as Trump said he’s considering, while getting rid of either the individual mandate — the requirement that people get insured — or the subsidies that motivate low-income healthy people to join the insurance rolls could also create instability in the insurance market. Without the necessary mix of healthy people in a plan to offset the costs of insuring people with pre-existing conditions, premiums rise, becoming unaffordable for everyone.

An estimated 22 million people would lose their insurance if Congress and Trump implemented the changes outlined in the most recent reconciliation bill. Even if Trump tries to hang onto the provisions he mentioned after meeting with Obama, it’s unclear what he might do to keep all those Americans insured. Looking at his campaign stump speeches, and proposed legislation from other Republicans, we can make some educated guesses about what might happen. (...)

Trump has said he wants to dismantle several key elements of the law, chief among them the individual mandate. He’s also said he’d like to use “block grants” that would provide a fixed sum, with fewer federal regulations, to states to fund Medicaid. It’s an idea that also features in House Speaker Paul Ryan’s health care proposal. That’s different from Medicaid expansion under the ACA, which requires that states cover everyone below 138 percent of the federal poverty line. It’s not clear how many of the millions of people who currently have Medicaid coverage under the ACA expansion would remain eligible for government assistance.

The individual mandate is a little more complicated. At one point, it was seen along most of the political spectrum as a promising way to reduce the number of uninsured people in the United States; requiring healthy people to sign up for coverage was supposed to ensure that premiums were affordable. The idea was originally floated by the conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation and was first brought to Congress by Republicans in the 1990s. The mandate has since become one of the most despised aspects of the law.

But there isn’t a clear policy proposal with bipartisan support for how to get more healthy people into the insurance market in the absence of an individual mandate and insurance subsidies. Trump has proposed creating high-risk pool insurance programs, essentially plans that people with pre-existing conditions can buy into. These types of plans existed in many states before the passage of the ACA and by design are not self-sustaining because members use significantly more health care than they can afford. That means they require significant federal dollars ($25 billion in the case of a plan from Ryan), which is one of the many reasons high-risk pools are divisive among Republican lawmakers.