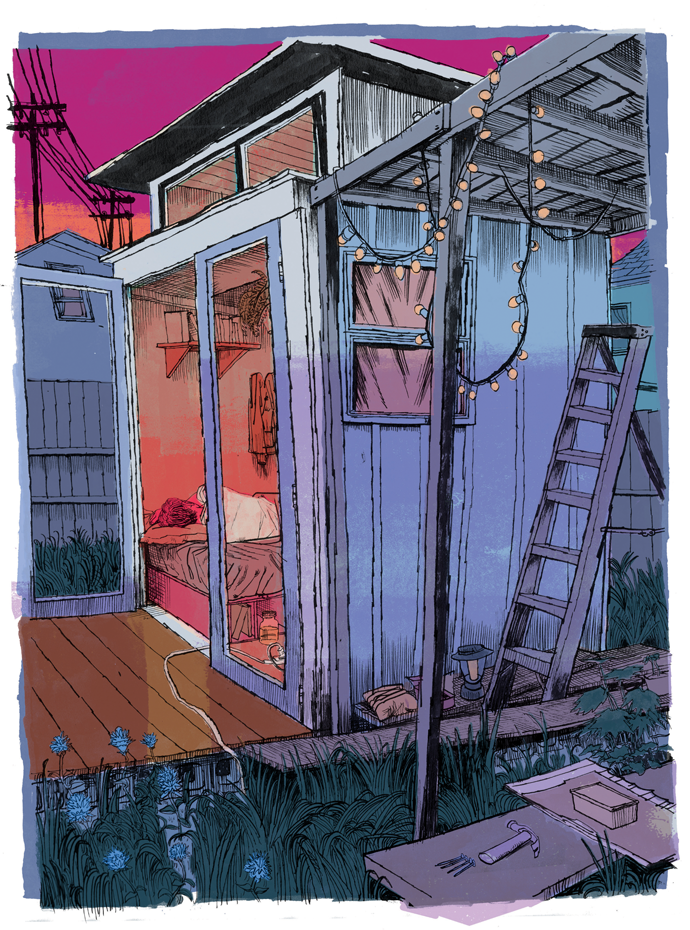

That year, the year of the Ghost Ship fire, I lived in a shack. I’d found the place just as September’s Indian summer was giving way to a wet October. There was no plumbing or running water to wash my hands or brush my teeth before sleep. Electricity came from an extension cord that snaked through a yard of coyote mint and monkey flower and up into a hole I’d drilled in my floorboards. The structure was smaller than a cell at San Quentin—a tiny house or a huge coffin, depending on how you looked at it—four by eight and ten feet tall, so cramped it fit little but a mattress, my suit jackets and ties, a space heater, some novels, and the mason jar I peed in.

The exterior of my hermitage was washed the color of runny egg yolk. Two redwood French doors with plexiglass windows hung cockeyed from creaky hinges at the entrance, and a combination lock provided meager security against intruders. White beadboard capped the roof, its brim shading a front porch set on cinder blocks.

After living on the East Coast for eight years, I’d recently left New York City to take a job at an investigative reporting magazine in San Francisco. If it seems odd that I was a fully employed editor who lived in a thirty-two-square-foot shack, that’s precisely the point: my situation was evidence of how distorted the Bay Area housing market had become, the brutality inflicted upon the poor now trickling up to everyone but the super-rich. The problem was nationwide, although, as Californians tend to do, they’d taken this trend to an extreme. Across the state, a quarter of all apartment dwellers spent half of their incomes on rent. Nearly half of the country’s unsheltered homeless population lived in California, even while the state had the highest concentration of billionaires in the nation. In the Bay Area, including West Oakland, where my shack was located, the crisis was most acute. Tent cities had sprung up along the sidewalks, swarming with capitalism’s refugees. Telegraph, Mission, Market, Grant: every bridge and overpass had become someone’s roof.

After living on the East Coast for eight years, I’d recently left New York City to take a job at an investigative reporting magazine in San Francisco. If it seems odd that I was a fully employed editor who lived in a thirty-two-square-foot shack, that’s precisely the point: my situation was evidence of how distorted the Bay Area housing market had become, the brutality inflicted upon the poor now trickling up to everyone but the super-rich. The problem was nationwide, although, as Californians tend to do, they’d taken this trend to an extreme. Across the state, a quarter of all apartment dwellers spent half of their incomes on rent. Nearly half of the country’s unsheltered homeless population lived in California, even while the state had the highest concentration of billionaires in the nation. In the Bay Area, including West Oakland, where my shack was located, the crisis was most acute. Tent cities had sprung up along the sidewalks, swarming with capitalism’s refugees. Telegraph, Mission, Market, Grant: every bridge and overpass had become someone’s roof.Down these same streets, tourists scuttered along on Segways and techies surfed the hills on motorized longboards, transformed by their wealth into children, just as the sidewalk kids in cardboard boxes on Haight or in People’s Park aged overnight into decrepit adults, the former racing toward the future, the latter drifting away from it.

To my mother and girlfriend back East, the “shack situation” was a problem to be solved. “Can we help you find another place?” “Can you just find roommates and live in a house?” But the shack was the solution, not the problem. (...)

Growing up in rural upstate New York, raised on food stamps and free school lunches, my dad off to prison for a spell, I never met anyone who made a living in publishing. But in 2007 I was accepted into U.C. Berkeley’s graduate program in journalism. I saw the school, and the scholarship it offered, as a possible entrée to a world I had believed wasn’t available to working-class people like me. So, at age twenty-five, I stuffed my Toyota Camry with books and clothes, and, accompanied by my then girlfriend and $500 in savings, I drove west to a state I’d never even visited, hoping Cormac McCarthy was right when he wrote, in No Country for Old Men, that the “best way to live in California is to be from somewheres else.”

The Great Recession had not yet hit, and cheap housing was easy enough to find, even for someone with no credit or bank account. When my girlfriend and I broke up, I landed at a ratty mansion, Fort Awesome, in South Berkeley. My rent for one of the mansion’s eleven bedrooms was about $300 a month. There was an outdoor kitchen the size of a large cottage, three guest shacks, and a wood-fired hot tub built from a redwood wine vat. About thirty people lived on the compound, including a few children. The adult residents were a mix of hippies, crusties, anarchists, outcast techies, chemistry grad students, addicts, and activists—a cohort that shouldn’t have lasted a day, but in fact had lasted six years, ever since some of the residents had banded together and, with the help of a community land trust, bought the plot for $600,000. (Today, the property is worth about $4 million.)

I was unwittingly among the vanguard of a wave of gentrification—a transient “creative” living in a “rough” neighborhood not yet fully colonized by the white middle class—and sometimes it was tense. I almost brawled one night with three teens who shoved me out front of a liquor store; another night I fought off a mugger and came home with a black eye. But otherwise the Bay was astonishingly convivial—for the first time in Oakland’s history, the city’s populations of African-American, Latino, Asian, and white residents were almost exactly equal in size—and I fell in love with dozens of squats, warehouses, galleries, and underground bars, where black hyphy kids and white gutter punks and queer Asian ravers all hung out and partied together, paving the way for later spaces like Ghost Ship. It felt like the perfect time to be there, like I imagined the Eighties on New York City’s Lower East Side. (...)

The Great Recession had not yet hit, and cheap housing was easy enough to find, even for someone with no credit or bank account. When my girlfriend and I broke up, I landed at a ratty mansion, Fort Awesome, in South Berkeley. My rent for one of the mansion’s eleven bedrooms was about $300 a month. There was an outdoor kitchen the size of a large cottage, three guest shacks, and a wood-fired hot tub built from a redwood wine vat. About thirty people lived on the compound, including a few children. The adult residents were a mix of hippies, crusties, anarchists, outcast techies, chemistry grad students, addicts, and activists—a cohort that shouldn’t have lasted a day, but in fact had lasted six years, ever since some of the residents had banded together and, with the help of a community land trust, bought the plot for $600,000. (Today, the property is worth about $4 million.)

I was unwittingly among the vanguard of a wave of gentrification—a transient “creative” living in a “rough” neighborhood not yet fully colonized by the white middle class—and sometimes it was tense. I almost brawled one night with three teens who shoved me out front of a liquor store; another night I fought off a mugger and came home with a black eye. But otherwise the Bay was astonishingly convivial—for the first time in Oakland’s history, the city’s populations of African-American, Latino, Asian, and white residents were almost exactly equal in size—and I fell in love with dozens of squats, warehouses, galleries, and underground bars, where black hyphy kids and white gutter punks and queer Asian ravers all hung out and partied together, paving the way for later spaces like Ghost Ship. It felt like the perfect time to be there, like I imagined the Eighties on New York City’s Lower East Side. (...)

Across the street from my shack was Easy Liquor. A few weeks earlier, I’d been walking home in a downpour when I stumbled on a shirtless man circling its parking lot, shouting angrily, his hands clutched over his stomach. I asked if I could help. “Pull it out!” he shouted, and he shook his fists at me, revealing a knife handle where his belly button should have been. Another evening, on West MacArthur, I watched a large man shove his shopping cart into the path of a techie on a bicycle. The techie swerved and fell, and the homeless man put one foot on his victim’s chest and tugged at his Google laptop bag. “Help me!” the techie shouted as they played tug-of-war. I sprinted over and pushed the two men apart, yelling, “Get the fuck out of here and don’t come back!” I was talking to them both.

My neighbors’ homes were mostly blighted bungalows with peeling stucco, dust-bowl lawns, and barbed-wire fences. Men bench-pressed weights in driveways. Cars left on the street overnight would often appear the next morning with smashed windshields and cinder-block tires. The neighborhood’s boundaries were drawn by the “wrong” side of the BART train tracks and Telegraph Avenue to the east, bleak San Pablo Avenue to the west, and its southern and northern borders were marked by 35th Street and Ashby Avenue, beyond which were the newly bourgeois enclaves of Temescal and Emeryville. It wasn’t really a coherent neighborhood but its proximity to BART and the general scarcity of housing in the Bay had led developers to try to rebrand it “NOBE” (North Oakland Berkeley Emeryville), an absurd neologism I never once heard used except by real estate boosters.

Yet the rebranding was working, at least on paper. I seldom saw well-to-do white people on the streets, except when they were hurrying home or being mugged, but two- and three-bedroom cottages in the neighborhood were going on the market for $1.5 million, $2 million, and sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars more, often bought in cash by coders or executives who’d come east from San Francisco or west from the eastern seaboard to work for LinkedIn or Twitter or Atlassian or Oracle. As soon as a for sale sign went down, the ghetto bungalow behind it would be remodeled, landscaped, and encircled by a steel gate. The new inhabitants would only appear in public twice a day. In the morning, the jaws of their gated driveways opened, spitting tasteless Teslas and BMWs out into the streets, their drivers racing past the Palms, the Bay View, the Nights Inn, and Easy Liquor en route to the freeway or BART’s police-patrolled parking lot. At night, their gates would open to swallow them again, so they might sleep safely in the bellies of the beasts they called home, safe from the chaos outside.

At the end of our block was a monument to the housing wars: an eight-story, 105-unit, half-completed condo building that no one had ever lived in, and that no one ever would, casting its Hindenburg-size shadow over my shack. Just before my return to California, and amid rumors of anti-gentrification arsons, it mysteriously caught fire. This blaze devoured more than $35 million in labor and materials, and now the steel skeleton bowed and buckled. The entire top floor had collapsed, and the facade was seared with black smoke stains. (When someone torched this same building again several months later, police decided definitively that it was arson. I recall riding through the smoke on my bike that day.) As a result, the funders, Holliday Development, had ringed the property’s perimeter with chain-link and posted a twenty-four-hour armed sentry in a little matchbox booth inside the fence, a fat, tired man who waved to me cheerily when I cycled by.

Beside the half-destroyed condo complex was the 580 on-ramp to San Francisco. Clustered there on the highway’s margins was yet another of the city’s countless, nameless tent cities, a patchwork of a few dozen tarps and tents lit up at night by flaming oil drums. Beyond this homeless depot was Home Depot. I locked my bike outside the store and wandered the immaculate fluorescent-lit aisles. I bought four sheets of O.S.B. board, a box of three-inch drywall screws, and an armload of two-by-fours. Outside with my haul, I heard the loud thunk-thunk-thunk of E.D.M. and the squall of rubber tires skidding into the parking lot—Jenny’s Jeep, a crack down the center of the windshield like a busted smile, swerved into view and stopped in front of me, Jenny’s grinning face and tousled black hair framed by the rolled-down window.

“Check out this cute work outfit I bought,” she said, jumping out of the Jeep and modeling a pair of black thrift-store overalls.

“Portrait of an urban homesteader,” I said. (...)

Living in the shack, I came to realize that part of my motivation in moving back to the Bay Area was an urge to return to my younger self, a desire for freedom from the pressures of adulthood. After grad school at Berkeley, I’d gone to New York City, wanting to be a writer—but there weren’t, and aren’t, really full-time jobs for writers, not the kind I wanted to be, anyway. So I chose to become an editor, which seemed to be a way to split the difference between the precarity of the artist and the banality of the white-collar wage slave. But my role in the middle class was by no means secure or guaranteed no matter how hard I worked, and I had come to feel deceived by the mirage of upward mobility: after almost a decade of uninterrupted employment, of doing everything “right,” I owned no property, I had no stocks, no investments, no wealth, no inheritance, no safety net or support system beyond a few thousand dollars in my savings account. One disaster—being fired, sustaining a serious injury, needing to help out a desperate friend—could wipe me out, and if that happened, what would I have gained in a decade as an editor? I had decided I no longer cared about ever becoming middle-class; the cost of earning a living this way was too high. The terror of poverty had become far less frightening than the wages of having wasted my life.

“It is a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out,” George Orwell wrote in Down and Out in Paris and London. “You have talked so often of going to the dogs—and well, here are the dogs, and you have reached them, and you can stand it. It takes off a lot of anxiety.” (...)

The powerful thing about smallness, it occurred to me, isn’t actually smallness for its own sake—the point, instead, is a matter of scale. If you reduce the size of your life enough, then the smallest change can be a profound improvement. Yet the hardest thing is to recognize your smallness without being diminished by it. In my shack I was always balancing that tension—I didn’t want to become so small that I disappeared, I just wanted to hide for a little while.

My neighbors’ homes were mostly blighted bungalows with peeling stucco, dust-bowl lawns, and barbed-wire fences. Men bench-pressed weights in driveways. Cars left on the street overnight would often appear the next morning with smashed windshields and cinder-block tires. The neighborhood’s boundaries were drawn by the “wrong” side of the BART train tracks and Telegraph Avenue to the east, bleak San Pablo Avenue to the west, and its southern and northern borders were marked by 35th Street and Ashby Avenue, beyond which were the newly bourgeois enclaves of Temescal and Emeryville. It wasn’t really a coherent neighborhood but its proximity to BART and the general scarcity of housing in the Bay had led developers to try to rebrand it “NOBE” (North Oakland Berkeley Emeryville), an absurd neologism I never once heard used except by real estate boosters.

Yet the rebranding was working, at least on paper. I seldom saw well-to-do white people on the streets, except when they were hurrying home or being mugged, but two- and three-bedroom cottages in the neighborhood were going on the market for $1.5 million, $2 million, and sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars more, often bought in cash by coders or executives who’d come east from San Francisco or west from the eastern seaboard to work for LinkedIn or Twitter or Atlassian or Oracle. As soon as a for sale sign went down, the ghetto bungalow behind it would be remodeled, landscaped, and encircled by a steel gate. The new inhabitants would only appear in public twice a day. In the morning, the jaws of their gated driveways opened, spitting tasteless Teslas and BMWs out into the streets, their drivers racing past the Palms, the Bay View, the Nights Inn, and Easy Liquor en route to the freeway or BART’s police-patrolled parking lot. At night, their gates would open to swallow them again, so they might sleep safely in the bellies of the beasts they called home, safe from the chaos outside.

At the end of our block was a monument to the housing wars: an eight-story, 105-unit, half-completed condo building that no one had ever lived in, and that no one ever would, casting its Hindenburg-size shadow over my shack. Just before my return to California, and amid rumors of anti-gentrification arsons, it mysteriously caught fire. This blaze devoured more than $35 million in labor and materials, and now the steel skeleton bowed and buckled. The entire top floor had collapsed, and the facade was seared with black smoke stains. (When someone torched this same building again several months later, police decided definitively that it was arson. I recall riding through the smoke on my bike that day.) As a result, the funders, Holliday Development, had ringed the property’s perimeter with chain-link and posted a twenty-four-hour armed sentry in a little matchbox booth inside the fence, a fat, tired man who waved to me cheerily when I cycled by.

Beside the half-destroyed condo complex was the 580 on-ramp to San Francisco. Clustered there on the highway’s margins was yet another of the city’s countless, nameless tent cities, a patchwork of a few dozen tarps and tents lit up at night by flaming oil drums. Beyond this homeless depot was Home Depot. I locked my bike outside the store and wandered the immaculate fluorescent-lit aisles. I bought four sheets of O.S.B. board, a box of three-inch drywall screws, and an armload of two-by-fours. Outside with my haul, I heard the loud thunk-thunk-thunk of E.D.M. and the squall of rubber tires skidding into the parking lot—Jenny’s Jeep, a crack down the center of the windshield like a busted smile, swerved into view and stopped in front of me, Jenny’s grinning face and tousled black hair framed by the rolled-down window.

“Check out this cute work outfit I bought,” she said, jumping out of the Jeep and modeling a pair of black thrift-store overalls.

“Portrait of an urban homesteader,” I said. (...)

Living in the shack, I came to realize that part of my motivation in moving back to the Bay Area was an urge to return to my younger self, a desire for freedom from the pressures of adulthood. After grad school at Berkeley, I’d gone to New York City, wanting to be a writer—but there weren’t, and aren’t, really full-time jobs for writers, not the kind I wanted to be, anyway. So I chose to become an editor, which seemed to be a way to split the difference between the precarity of the artist and the banality of the white-collar wage slave. But my role in the middle class was by no means secure or guaranteed no matter how hard I worked, and I had come to feel deceived by the mirage of upward mobility: after almost a decade of uninterrupted employment, of doing everything “right,” I owned no property, I had no stocks, no investments, no wealth, no inheritance, no safety net or support system beyond a few thousand dollars in my savings account. One disaster—being fired, sustaining a serious injury, needing to help out a desperate friend—could wipe me out, and if that happened, what would I have gained in a decade as an editor? I had decided I no longer cared about ever becoming middle-class; the cost of earning a living this way was too high. The terror of poverty had become far less frightening than the wages of having wasted my life.

“It is a feeling of relief, almost of pleasure, at knowing yourself at last genuinely down and out,” George Orwell wrote in Down and Out in Paris and London. “You have talked so often of going to the dogs—and well, here are the dogs, and you have reached them, and you can stand it. It takes off a lot of anxiety.” (...)

The powerful thing about smallness, it occurred to me, isn’t actually smallness for its own sake—the point, instead, is a matter of scale. If you reduce the size of your life enough, then the smallest change can be a profound improvement. Yet the hardest thing is to recognize your smallness without being diminished by it. In my shack I was always balancing that tension—I didn’t want to become so small that I disappeared, I just wanted to hide for a little while.

by Wes Enzinna, Harper's | Read more:

Image: Matt Rota