My book, Designing Data-Intensive Applications, recently passed the milestone of 100,000 copies sold. Last year, it was the second-best-selling book in O’Reilly’s entire catalogue, second only to Aurélien Géron’s machine learning book. Machine learning is obviously a hot topic, so I am quite content with coming second to it! 😄

To me, the success of this book was totally unexpected: while I was writing it, I thought that it was going to be a bit niche, and I set myself the goal of selling 10,000 copies over the lifetime of the book. Having passed that goal tenfold, this seems like a good opportunity to look back and reflect on the process. I don’t want to make this post too self-congratulatory, but rather I will try to share some insights into the business of book-writing.

To me, the success of this book was totally unexpected: while I was writing it, I thought that it was going to be a bit niche, and I set myself the goal of selling 10,000 copies over the lifetime of the book. Having passed that goal tenfold, this seems like a good opportunity to look back and reflect on the process. I don’t want to make this post too self-congratulatory, but rather I will try to share some insights into the business of book-writing.

Is it financially worth it?

Most books make very little money for both authors and publishers, but then occasionally something like Harry Potter comes along. If you are considering writing a book, I strongly recommend that you estimate the value of your future royalties to be close to zero. Like starting a band with friends and hoping to become rock stars, it’s difficult to predict in advance what will be a hit and what will flop. Maybe this applies less to technical books than to fiction and music, but I suspect that even with technical books, there are a small number of hits, and most books sell quite modest numbers.

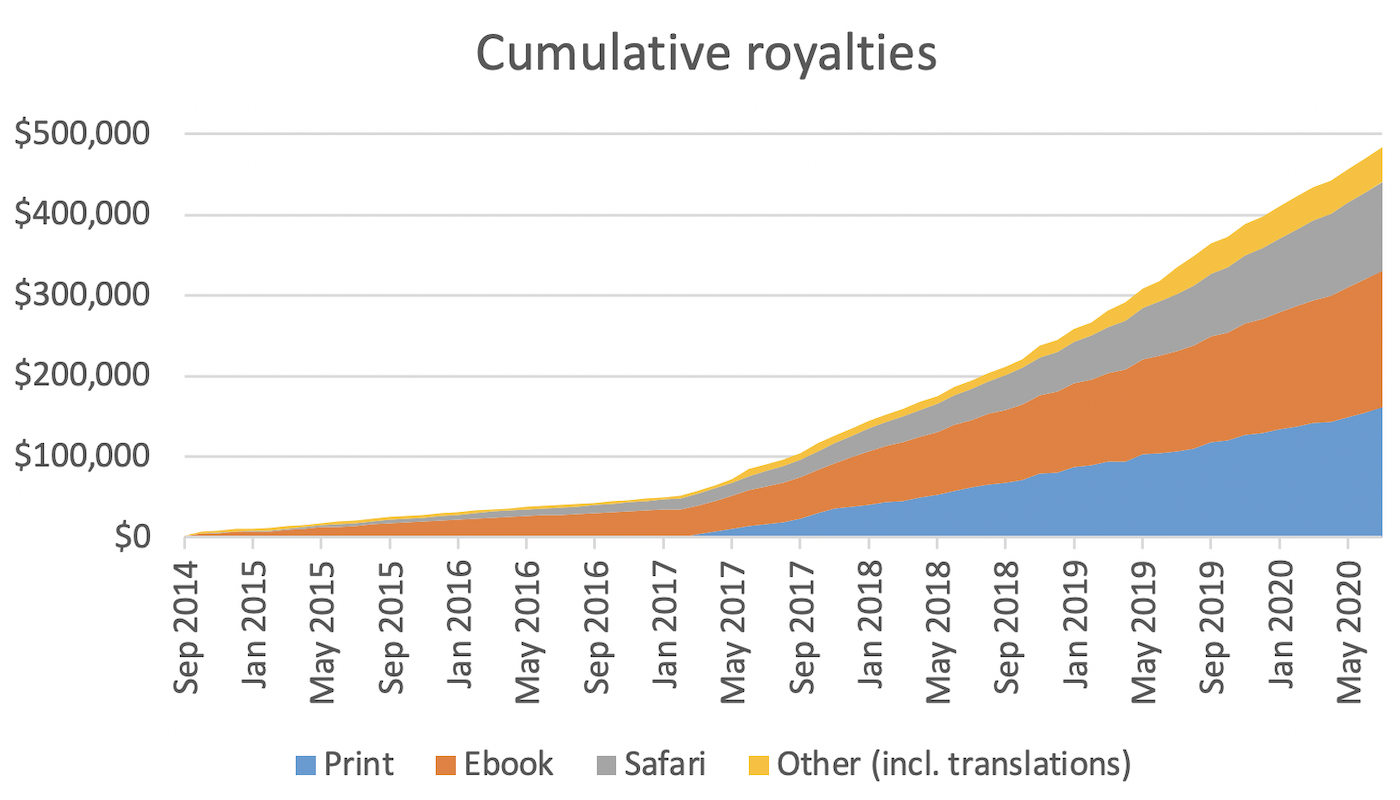

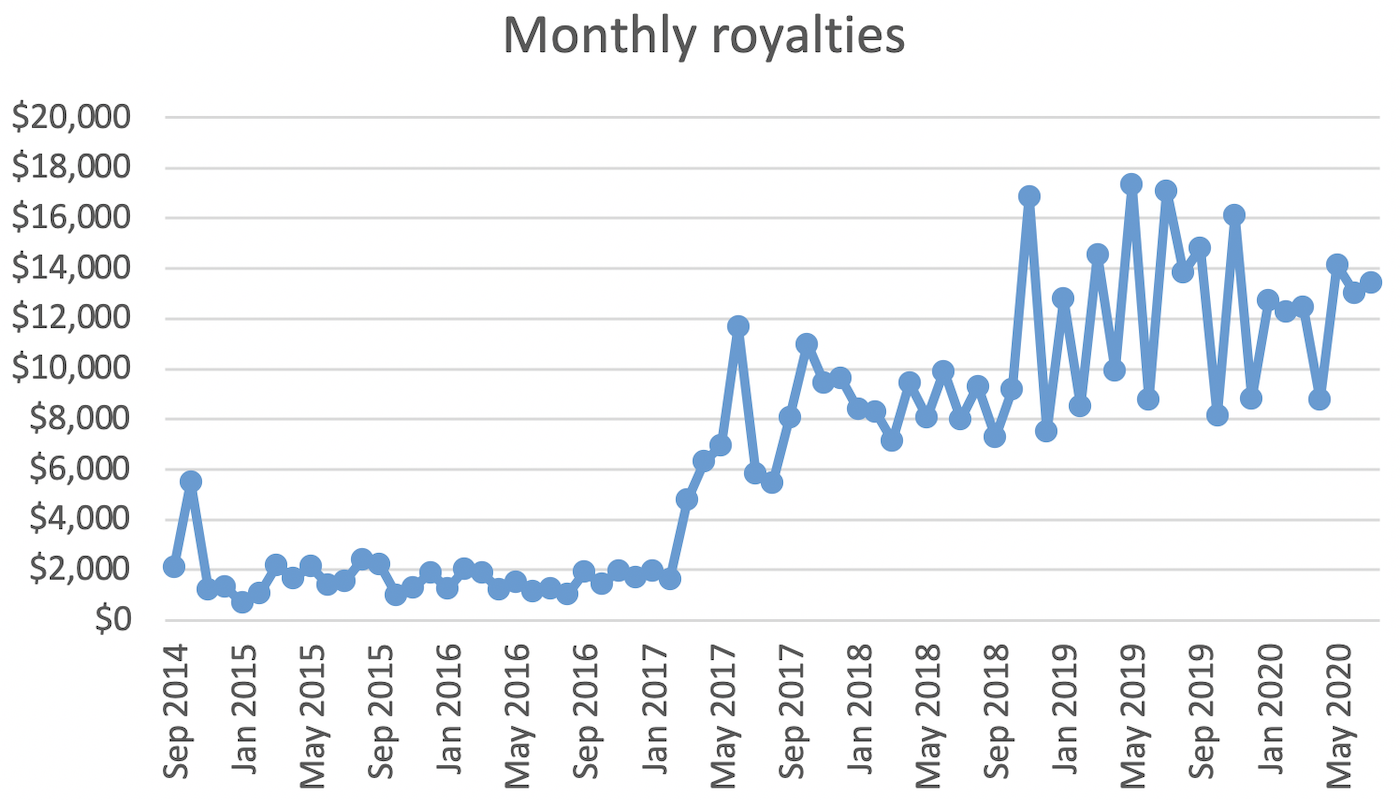

That said, in my case, I am happy to report that writing this book has in retrospect turned out to be a financially sound decision. These graphs show the royalties I have been paid since the book first went on sale:

For the first 2½ years the book was in “early release”: during this period I was still writing, and we released it in unedited form, one chapter at a time, as ebook only. Then in March 2017 the book was officially published, and the print edition went on sale. Since then, the sales have fluctuated from month to month, but on average they have stayed remarkably constant. At some point I would expect the market to become saturated (i.e. most people who were going to buy the book have already bought it), but that does not seem to have happened yet: indeed, sales noticeably increased in late 2018 (I don’t know why). The x axis ends in July 2020 because from the time of sale, it takes a couple of months for the money to trickle through the system.

My contract with the publisher specifies that I get 25% of publisher revenue from ebooks, online access, and licensing, 10% of revenue from print sales, and 5% of revenue from translations. That’s a percentage of the wholesale price that retailers/distributors pay to the publisher, so it doesn’t include the retailers’ markup. The figures in this section are the royalties I was paid, after the retailer and publisher have taken their cut, but before tax.

The total sales since the beginning have been (in US dollars):

- Print: 68,763 copies, $161,549 royalties ($2.35/book)

- Ebook: 33,420 copies, $169,350 royalties ($5.07/book)

- O’Reilly online access (formerly called Safari Books Online): $110,069 royalties (I don’t get readership numbers for this channel)

- Translations: 5,896 copies, $8,278 royalties ($1.40/book)

- Other licensing and sponsorship: $34,600 royalties

- Total: 108,079 copies, $477,916

Now, in retrospect, it turns out that those 2.5 years were a good investment, because the income that this work has generated is in the same ballpark as the Silicon Valley software engineering salary (including stock and benefits) I could have received in the same time if I hadn’t quit LinkedIn in 2014 to work on the book. But of course I didn’t know that at the time! The royalties could easily have turned out to be a factor of 10 lower, in which case it would have been a financially much less compelling proposition.

by Martin Kleppmann | Read more:

Images: Martin Kleppmann