Tuesday, August 31, 2021

Dialogues Between Neuroscience and Society: Music and the Brain With Pat Metheny

Tuesday, August 24, 2021

How Should an Influencer Sound?

For 10 straight years, the most popular way to introduce oneself on YouTube has been a single phrase: “Hey guys!” That’s pretty obvious to anyone who’s ever watched a YouTube video about, well, anything, but the company still put in the energy to actually track the data over the past decade. “What’s up” and “good morning” come in at second and third, but “hey guys” has consistently remained in the top spot. (Here is a fun supercut of a bunch of YouTubers saying it until the phrase ceases to mean anything at all.)

This is not where the sonic similarities of YouTubers, regardless of their content, end. For nearly as long as YouTube has existed, people have been lamenting the phenomenon of “YouTube voice,” or the slightly exaggerated, over-pronounced manner of speaking beloved by video essayists, drama commentators, and DIY experts on the platform. The ur-example cited is usually Hank Green, who’s been making videos on everything from the American health care system to the “Top 10 Freaking Amazing Explosions” since literally 2007.

Actual scholars have attempted to describe what YouTube voice sounds like. Speech pathologist and PhD candidate Erin Hall told Vice that there are two things happening here: “One is the actual segments they’re using — the vowels and consonants. They’re over-enunciating compared to casual speech, which is something newscasters or radio personalities do.” Second: “They’re trying to keep it more casual, even if what they’re saying is standard, adding a different kind of intonation makes it more engaging to listen to.”

In an investigation into YouTube voice, the Atlantic drew from several linguists to determine what specific qualities this manner of speaking shares. Essentially, it’s all about pronunciation and pacing. On camera, it takes more effort to keep someone interested (see also: exaggerated hand and facial motions). “Changing of pacing — that gets your attention,” said linguistics professor Naomi Baron. Baron noted that YouTubers tended to overstress both vowels and consonants, such as someone saying “exactly” like “eh-ckzACKTly.” She guesses that the style stems in part from informal news broadcast programs or “infotainment” like The Daily Show. Another, Mark Liberman of the University of Pennsylvania, put it bluntly: It’s “intellectual used-car-salesman voice,” he wrote. He also compared it to a carnival barker. (...)

Last week a TikTok came on my For You page that explored digital accents. TikToker @Averybrynn was referringspecifically to what she called the “beauty YouTuber dialect,” which she described as “like they weirdly pronounce everything just a little bit too much in these small little snippets?” What makes it distinct from regular YouTube voice is that each word tends to be longer than it should, while also being bookended by a staccato pause. There’s also a common inclination to turn short vowels into long vowels, like saying “thee” instead of “the.” Others in the comments pointed out the repeated use of the first person plural when referring to themselves (“and now we’re gonna go in with a swipe of mascara”), while one linguistics major noted that this was in fact a “sociolect,” not a dialect, because it refers to a social group.

It’s the sort of speech typically associated with female influencers who, by virtue of the job, we assume are there to endear themselves to the audience or present a trustworthy sales pitch. But what’s most interesting to watch about YouTube voice and the influencer accent is how normal people have adapted to it in their own, regular-person TikTok videos and Instagram stories. If you listen closely to enough people’s front-facing camera videos, you’ll hear a voice that sounds somewhere between a TED Talk and sponsored content, perhaps even within your own social circles. Is this a sign that as influencer culture bleeds into our everyday lives, many of the quirks that professionals use will become normal for us too? Maybe! Is it a sign that social platforms are turning us all into salespeople? Also maybe!

But here’s the question I haven’t heard anyone ask yet: If everyone finds these ways of speaking annoying to some degree, then how should people actually talk into the camera?

by Rebecca Jennings, Vox | Read more:

Image: YouTube/Anyone Can Play Guitar

[ed. Got the link for this article from one of my top three favorite online guitar instructors: Adrian Woodward, who normally sounds like a cross between Alfred Hitchcock and the Geico gecko. Here he tries a YouTube voice for fun. If you're a guitar player, do check out his instruction videos on YouTube at Anyone Can Play Guitar. High quality, and great dry personality.]

This is not where the sonic similarities of YouTubers, regardless of their content, end. For nearly as long as YouTube has existed, people have been lamenting the phenomenon of “YouTube voice,” or the slightly exaggerated, over-pronounced manner of speaking beloved by video essayists, drama commentators, and DIY experts on the platform. The ur-example cited is usually Hank Green, who’s been making videos on everything from the American health care system to the “Top 10 Freaking Amazing Explosions” since literally 2007.

Actual scholars have attempted to describe what YouTube voice sounds like. Speech pathologist and PhD candidate Erin Hall told Vice that there are two things happening here: “One is the actual segments they’re using — the vowels and consonants. They’re over-enunciating compared to casual speech, which is something newscasters or radio personalities do.” Second: “They’re trying to keep it more casual, even if what they’re saying is standard, adding a different kind of intonation makes it more engaging to listen to.”

In an investigation into YouTube voice, the Atlantic drew from several linguists to determine what specific qualities this manner of speaking shares. Essentially, it’s all about pronunciation and pacing. On camera, it takes more effort to keep someone interested (see also: exaggerated hand and facial motions). “Changing of pacing — that gets your attention,” said linguistics professor Naomi Baron. Baron noted that YouTubers tended to overstress both vowels and consonants, such as someone saying “exactly” like “eh-ckzACKTly.” She guesses that the style stems in part from informal news broadcast programs or “infotainment” like The Daily Show. Another, Mark Liberman of the University of Pennsylvania, put it bluntly: It’s “intellectual used-car-salesman voice,” he wrote. He also compared it to a carnival barker. (...)

Last week a TikTok came on my For You page that explored digital accents. TikToker @Averybrynn was referringspecifically to what she called the “beauty YouTuber dialect,” which she described as “like they weirdly pronounce everything just a little bit too much in these small little snippets?” What makes it distinct from regular YouTube voice is that each word tends to be longer than it should, while also being bookended by a staccato pause. There’s also a common inclination to turn short vowels into long vowels, like saying “thee” instead of “the.” Others in the comments pointed out the repeated use of the first person plural when referring to themselves (“and now we’re gonna go in with a swipe of mascara”), while one linguistics major noted that this was in fact a “sociolect,” not a dialect, because it refers to a social group.

It’s the sort of speech typically associated with female influencers who, by virtue of the job, we assume are there to endear themselves to the audience or present a trustworthy sales pitch. But what’s most interesting to watch about YouTube voice and the influencer accent is how normal people have adapted to it in their own, regular-person TikTok videos and Instagram stories. If you listen closely to enough people’s front-facing camera videos, you’ll hear a voice that sounds somewhere between a TED Talk and sponsored content, perhaps even within your own social circles. Is this a sign that as influencer culture bleeds into our everyday lives, many of the quirks that professionals use will become normal for us too? Maybe! Is it a sign that social platforms are turning us all into salespeople? Also maybe!

But here’s the question I haven’t heard anyone ask yet: If everyone finds these ways of speaking annoying to some degree, then how should people actually talk into the camera?

by Rebecca Jennings, Vox | Read more:

Image: YouTube/Anyone Can Play Guitar

[ed. Got the link for this article from one of my top three favorite online guitar instructors: Adrian Woodward, who normally sounds like a cross between Alfred Hitchcock and the Geico gecko. Here he tries a YouTube voice for fun. If you're a guitar player, do check out his instruction videos on YouTube at Anyone Can Play Guitar. High quality, and great dry personality.]

Friday, August 20, 2021

Tony Joe White - Behind the Music

[ed. Part 2 here. Been trying to learn some Tony Joe White guitar style lately. Great technique. If you're unfamiliar with him, or only know Rainy Night in Georgia and Polk Salad Annie, check out some of his other stuff on YouTube like this, this, this, and this whole album (Closer to the Truth). I love the story about Tina Turner recording a few of his songs. Starts at 30:25 - 34:30, and how he got into songwriting at 13:40 - 16:08.]

Thursday, August 5, 2021

American Gentry

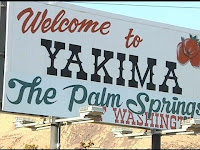

For the first eighteen years of my life, I lived in the very center of Washington state, in a city called Yakima. Shout-out to the self-proclaimed Palm Springs of Washington!

Yakima is a place I loved dearly and have returned to often over the years since, but I’ve never lived there again on a permanent basis. The same was true of most of my close classmates in high school: If they had left for college, most had never returned for longer than a few months at a time. Practically all of them now lived in major metro areas scattered across the country, not our hometown with its population of 90,000.

There were a lot of talented and interesting people in that group, most of whom I had more or less lost touch with over the intervening years. A few years ago, I had the idea of interviewing them to ask precisely why they haven’t come back and how they felt about it. That piece never really came together, but it was fascinating talking to a bunch of folks I hadn’t spoken to in years regarding what they thought and how they felt about home.

For the most part, their answers to my questions revolved around work. Few bore our hometown much, if any, ill will; they’d simply gone away to college, many had gone to graduate school after that, and the kinds of jobs they were now qualified for didn’t really exist in Yakima. Its economy revolved then, and revolves to an ever greater extent now, around commercial agriculture. There are other employers, but not much demand for highly educated professionals - which is generally what my high-achieving classmates became - relative to a larger city.

The careers they ended up pursuing, in corporate or management consulting, non-profits, finance, media, documentary filmmaking, and the like, exist to a much greater degree in major metropolitan areas. There are a few in Portland, and others in New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Austin, and me in Phoenix. A great many of my former classmates live in Seattle. We were lucky that one of the country’s most booming major metros, with the most highly educated Millennial population in the country, is 140 miles away from where we grew up on the other side of the Cascade Mountains: close in absolute terms, but a world away culturally, economically, and politically.

Only a few have returned to Yakima permanently after their time away. Those who have seem to like it well enough; for a person lucky and accomplished enough to get one of those reasonably affluent professional jobs, Yakima - like most cities in the US - isn’t a bad place to live. The professional-managerial class, and the older Millennials in the process of joining it, has a pretty excellent material standard of living regardless of precisely where they’re at.

But very few of my classmates really belonged to the area’s elite. It wasn’t a city of international oligarchs, but one dominated by its wealthy, largely agricultural property-owning class. They mostly owned, and still own, fruit companies: apples, cherries, peaches, and now hops and wine-grapes. The other large-scale industries in the region, particularly commercial construction, revolve at a fundamental level around agriculture: They pave the roads on which fruits and vegetables are transported to transshipment points, build the warehouses where the produce is stored, and so on.

Commercial agriculture is a lucrative industry, at least for those who own the orchards, cold storage units, processing facilities, and the large businesses that cater to them. They have a trusted and reasonably well-paid cadre of managers and specialists in law, finance, and the like - members of the educated professional-managerial class that my close classmates and I have joined - but the vast majority of their employees are lower-wage laborers. The owners are mostly white; the laborers are mostly Latino, a significant portion of them undocumented immigrants. Ownership of the real, core assets is where the region’s wealth comes from, and it doesn’t extend down the social hierarchy. Yet this bounty is enough to produce hilltop mansions, a few high-end restaurants, and a staggering array of expensive vacation homes in Hawaii, Palm Springs, and the San Juan Islands.

This class of people exists all over the United States, not just in Yakima. So do mid-sized metropolitan areas, the places where huge numbers of Americans live but which don’t figure prominently in the country’s popular imagination or its political narratives: San Luis Obispo, California; Odessa, Texas; Bloomington, Illinois; Medford, Oregon; Hilo, Hawaii; Dothan, Alabama; Green Bay, Wisconsin. (As an aside, part of the reason I loved Parks and Recreation was because it accurately portrayed life in a place like this: a city that wasn’t small, which served as the hub for a dispersed rural area, but which wasn’t tightly connected to a major metropolitan area.)

This kind of elite’s wealth derives not from their salary - this is what separates them from even extremely prosperous members of the professional-managerial class, like doctors and lawyers - but from their ownership of assets. Those assets vary depending on where in the country we’re talking about; they could be a bunch of McDonald’s franchises in Jackson, Mississippi, a beef-processing plant in Lubbock, Texas, a construction company in Billings, Montana, commercial properties in Portland, Maine, or a car dealership in western North Carolina. Even the less prosperous parts of the United States generate enough surplus to produce a class of wealthy people. Depending on the political culture and institutions of a locality or region, this elite class might wield more or less political power. In some places, they have an effective stranglehold over what gets done; in others, they’re important but not all-powerful.

Wherever they live, their wealth and connections make them influential forces within local society. In the aggregate, through their political donations and positions within their localities and regions, they wield a great deal of political influence. They’re the local gentry of the United States.

(Yes, that’s a real sign. It’s one of the few things outsiders tend to remember about Yakima, along with excellent cheeseburgers from Miner’s and one of the nation’s worst COVID-19 outbreaks.)

Yakima is a place I loved dearly and have returned to often over the years since, but I’ve never lived there again on a permanent basis. The same was true of most of my close classmates in high school: If they had left for college, most had never returned for longer than a few months at a time. Practically all of them now lived in major metro areas scattered across the country, not our hometown with its population of 90,000.

There were a lot of talented and interesting people in that group, most of whom I had more or less lost touch with over the intervening years. A few years ago, I had the idea of interviewing them to ask precisely why they haven’t come back and how they felt about it. That piece never really came together, but it was fascinating talking to a bunch of folks I hadn’t spoken to in years regarding what they thought and how they felt about home.

For the most part, their answers to my questions revolved around work. Few bore our hometown much, if any, ill will; they’d simply gone away to college, many had gone to graduate school after that, and the kinds of jobs they were now qualified for didn’t really exist in Yakima. Its economy revolved then, and revolves to an ever greater extent now, around commercial agriculture. There are other employers, but not much demand for highly educated professionals - which is generally what my high-achieving classmates became - relative to a larger city.

The careers they ended up pursuing, in corporate or management consulting, non-profits, finance, media, documentary filmmaking, and the like, exist to a much greater degree in major metropolitan areas. There are a few in Portland, and others in New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Austin, and me in Phoenix. A great many of my former classmates live in Seattle. We were lucky that one of the country’s most booming major metros, with the most highly educated Millennial population in the country, is 140 miles away from where we grew up on the other side of the Cascade Mountains: close in absolute terms, but a world away culturally, economically, and politically.

Only a few have returned to Yakima permanently after their time away. Those who have seem to like it well enough; for a person lucky and accomplished enough to get one of those reasonably affluent professional jobs, Yakima - like most cities in the US - isn’t a bad place to live. The professional-managerial class, and the older Millennials in the process of joining it, has a pretty excellent material standard of living regardless of precisely where they’re at.

But very few of my classmates really belonged to the area’s elite. It wasn’t a city of international oligarchs, but one dominated by its wealthy, largely agricultural property-owning class. They mostly owned, and still own, fruit companies: apples, cherries, peaches, and now hops and wine-grapes. The other large-scale industries in the region, particularly commercial construction, revolve at a fundamental level around agriculture: They pave the roads on which fruits and vegetables are transported to transshipment points, build the warehouses where the produce is stored, and so on.

Commercial agriculture is a lucrative industry, at least for those who own the orchards, cold storage units, processing facilities, and the large businesses that cater to them. They have a trusted and reasonably well-paid cadre of managers and specialists in law, finance, and the like - members of the educated professional-managerial class that my close classmates and I have joined - but the vast majority of their employees are lower-wage laborers. The owners are mostly white; the laborers are mostly Latino, a significant portion of them undocumented immigrants. Ownership of the real, core assets is where the region’s wealth comes from, and it doesn’t extend down the social hierarchy. Yet this bounty is enough to produce hilltop mansions, a few high-end restaurants, and a staggering array of expensive vacation homes in Hawaii, Palm Springs, and the San Juan Islands.

This class of people exists all over the United States, not just in Yakima. So do mid-sized metropolitan areas, the places where huge numbers of Americans live but which don’t figure prominently in the country’s popular imagination or its political narratives: San Luis Obispo, California; Odessa, Texas; Bloomington, Illinois; Medford, Oregon; Hilo, Hawaii; Dothan, Alabama; Green Bay, Wisconsin. (As an aside, part of the reason I loved Parks and Recreation was because it accurately portrayed life in a place like this: a city that wasn’t small, which served as the hub for a dispersed rural area, but which wasn’t tightly connected to a major metropolitan area.)

This kind of elite’s wealth derives not from their salary - this is what separates them from even extremely prosperous members of the professional-managerial class, like doctors and lawyers - but from their ownership of assets. Those assets vary depending on where in the country we’re talking about; they could be a bunch of McDonald’s franchises in Jackson, Mississippi, a beef-processing plant in Lubbock, Texas, a construction company in Billings, Montana, commercial properties in Portland, Maine, or a car dealership in western North Carolina. Even the less prosperous parts of the United States generate enough surplus to produce a class of wealthy people. Depending on the political culture and institutions of a locality or region, this elite class might wield more or less political power. In some places, they have an effective stranglehold over what gets done; in others, they’re important but not all-powerful.

Wherever they live, their wealth and connections make them influential forces within local society. In the aggregate, through their political donations and positions within their localities and regions, they wield a great deal of political influence. They’re the local gentry of the United States.

by Patrick Wyman, Perspectives: Past, Present, and Future | Read more:

Image: uncredited

[ed. I live 30 miles from Yakima, so this is of some interest.]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)