"Given the damage already wrought on the Nasdaq, there is a natural inclination to buy the dip. We believe that there is little merit in doing so. The current market climate is characterized by extremely unfavorable valuations, unfavorable trend uniformity, and hostile yield trends. This combination is what we define as a Crash Warning, and this climate has historically occurred in less than 4% of market history. That 4% of market history includes the 1929 crash and the 1987 crash, as well as a number of less memorable crashes and panics. We prefer to hedge until there is a rational prospect for market gains. When valuations are favorable, stocks are attractive from the standpoint of ‘investment’ – meaning that stock prices are attractive compared to the conservatively discounted value of cash flows which will be thrown off in the future. When trend uniformity is favorable, stocks are attractive from the standpoint of ‘speculation’ – meaning that regardless of valuation, investors are displaying an increased tolerance for risk which favors a further advance in prices.”– John P. Hussman, Ph.D., Hussman Investment Research & Insight, November 15, 2000Surveying the current condition of the financial markets, we presently observe a combination of still historically-extreme valuations, rising yet still only normalizing interest rates, measurably inadequate risk-premiums in both equities and bonds, and ragged, unfavorable market internals, suggesting continued risk-aversion among investors. In this context, it’s worth repeating what I’ve noted across decades of market cycles – a market collapse is nothing but risk-aversion meeting an inadequate risk-premium; rising yield pressure meeting an inadequate yield.

Emphatically, short-term oversold conditions can be followed anytime by fast, furious advances to clear those conditions. As I discuss in more detail below, we also pay ongoing attention to the uniformity or divergence of market internals (what I used to call “trend uniformity”). The above quote from 2000 explains why. “When trend uniformity is favorable, stocks are attractive from the standpoint of ‘speculation’ – meaning that regardless of valuation, investors are displaying an increased tolerance for risk, which favors a further advance in prices.” In that context, the only thing a decade of zero-interest policy did was to remove any reliable upper “limit” to valuations or risk-taking. Even we’ve adapted our discipline to reflect that reality. The danger comes when investors continue to ignore extreme valuations even after investor psychology has shifted to risk-aversion.

The opening quote is from November 15, 2000. From its March 24, 2000 bull market peak of 4816.35, the technology-heavy Nasdaq 100 index had already plunged by -36%. Yet from that lower level, it would go on to lose another -68% by October 2002. That outcome should not have been a surprise. On March 7, 2000, I observed, “Over time, price/revenue ratios come back in line. Currently, that would require an 83% plunge in tech stocks (recall the 1969-70 tech massacre). The plunge may be muted to about 65% given several years of revenue growth. If you understand values and market history, you know we’re not joking.”

At the 2000 market peak, a broad range of reliable valuations implied negative estimated S&P 500 total returns for over a decade, as they did in 1929, and as they unfortunately do today. This is what a decade of zero interest rate policy has set up for investors.

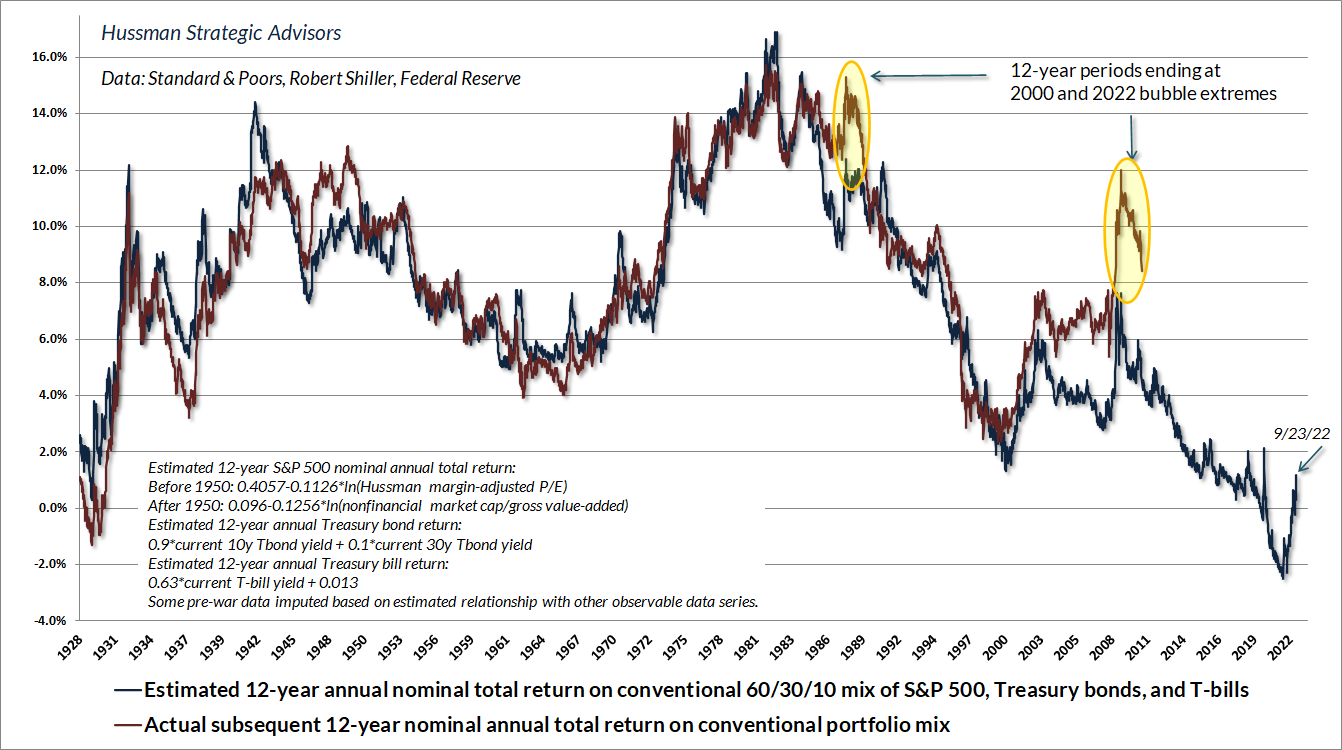

The chart below shows our best estimate of the expected 12-year total return for a conventional passive investment portfolio invested 60% in the S&P 500, 30% in Treasury bonds, and 10% in Treasury bills. Notice that recent market losses have markedly improved prospective returns for a passive investment allocation, yet only to a level of about 1% annually. Indeed, the expected return of the S&P 500 component is still negative.

A decade of deranged Federal Reserve zero-interest rate policy has exerted what former FDIC chair Sheila Bair recently described as a “corrosive” effect on the financial markets and the economy. Faced with zero interest rates, investors became convinced that they had no alternative but to speculate. As speculation drove valuations far beyond their historical norms, investors embraced the idea that valuations simply did not matter. Advancing prices in the rear-view mirror seemed to provide evidence that zero-interest rate cash was an unacceptable alternative to passively investing in stocks, regardless of price.

In 1934, following an 89% market collapse during the Great Depression, Benjamin Graham and David Dodd detailed the beliefs that investors had adopted during the speculative runup to the 1929 peak. They are identical to what we’ve observed in recent years. First, “that the records of the past were proving an undependable guide to investment”; second, “that the rewards offered by the future had become irresistibly alluring”; and third, “a companion theory that common stocks represented the most profitable and therefore the most desirable media for long-term investment.” Taken together, these beliefs ultimately contributed to “the notion that the desirability of a common stock was entirely independent of its price.” Surveying the rubble, Graham and Dodd observed, “The results of such a doctrine could not fail to be tragic.”

Encouraged by the same beliefs, investors drove S&P 500 valuations to levels even beyond the 1929 and 2000 extremes – levels that we associate with over a decade of negative expected returns even from current levels. At present, the stock and bond markets have declined enough to restore positive expected returns for a diversified portfolio that includes both stocks and bonds, but just barely. (...)

Keep in mind that periods of hypervaluation are not resolved in one fell swoop. To imagine otherwise is to minimize the discomfort, uncertainty, and alternation between fear and hope that the collapse of a bubble entails. The way that bubbles unfold into preposterous losses – 89%, 82%, 50%, 55%, and I expect this time between 50-70% – is through multiple periods of decline and even free-fall, punctuated by fast, furious “clearing rallies” that offer hope all the way down. By the time investors experience the second or third free-fall – and we’ve hardly experienced the first one yet – the psychology of investors is not “this is the bottom” – but rather, “there is no bottom.”

Aside from ignoring valuations and market internals, one of the behaviors that will get you eaten in a bear market is placing too much confidence in any single ‘capitulation.’ Speculative episodes typically unwind in waves. The steeper the starting valuations, the more waves one typically observes.– John P. Hussman, Ph.D., Making Friends with Bears Through Math, June 1, 2022Very little confidence in the equity market has been shaken – yet. Consider the surveys from the American Association of Individual Investors (AAII). Sentiment – talk – is lopsided at 60.9% bearish and just 17.7% bullish. Portfolio allocations – actions – are an entirely different story, with an above-average 64.5% allocation to equities, nowhere close to the 40% equity allocations that AAII respondents reported at the 1990, 2002, and 2009 market lows. Put simply, investors are clearly becoming uncomfortable, but in practice, they continue to defend the hill of extreme valuations, in the apparent belief that whatever risk remains must be short-term in nature. “After all,” investors have been trained to repeat, “it always comes back.” It’s easy to forget that the speculative valuations can be followed by S&P 500 returns below T-bills, and even below zero, for more than a decade. (...)

My advice for those who insist that profit margins are inexorably rising over time is simple: quantify it. Even if one runs an upward-sloping trendline through S&P 500 profit margins, one can only justify valuations 20-30% above historical norms, not 2.3-2.5 times those norms. For those that go further and insist that S&P 500 reported profit margins will remain at permanent record highs above 12%, despite a historical average of less than 7%, never exceeding 10% except amid trillions of dollars in pandemic subsidies since 2020, I can’t really help much, because these investors have already decided that history doesn’t matter.

by John P. Hussman, Ph.D, Hussman Funds | Read more:

Image: Hussman Strategic Advisors