The Five Spot was closed on Mondays, but on that March Monday Davis, Coltrane, and Evans had other business anyway: in Columbia Records’ 30th Street Studio, they were joining the alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Jimmy Cobb to begin making, under Miles’s leadership, what would become the bestselling, and arguably most beloved, jazz album of all time, Miles’s Kind of Blue. March 2 and April 22: three tunes recorded on the first date (“So What,” “Freddie Freeloader,” and “Blue in Green”), two on the second (“All Blues” and “Flamenco Sketches”). Every complete take but one (“Flamenco Sketches”) was a first take, the process similar, as Evans later wrote in the LP’s liner notes, to a genre of Japanese visual art in which black watercolor is applied spontaneously to a thin stretched parchment, with no unnatural or interrupted strokes possible, Miles’s cherished ideal of spontaneity achieved.

The quiet and enigmatic majesty of the resulting record both epitomizes jazz and transcends the genre. The album’s powerful and enduring mystique has made it widely beloved among musicians and music lovers of every category: jazz, rock, classical, rap. This is the story of the three geniuses who joined forces to create one of the great classics in Western music—how they rose up in the world, came together like a chance collision of particles in deep space, produced a brilliant flash of light, and then went on their separate ways to jazz immortality.

No musician ever goes into a record date expecting to make history; every man in Miles’s band had recorded dozens of times before. “Professionals,” Bill Evans said, “have to go in at 10 o’clock on a Wednesday and make a record and hope to catch a really good day.” On the face of it, there was nothing remarkable about Project B 43079. (...)

Outside the 30th Street Studio, Manhattan was Manhattaning: rounded buses and big yellow cabs grinding up and down the avenues; car horns and scraps of radio music and pedestrians’ voices echoing in the deep-shadowed side streets. Outside, the everyday clamor and clash of a city afternoon in late-winter 1959; inside, the densest quiet as a passage outside of time proceeded: the recording of CO 62291, the number that would come to be titled “So What,” leading off the album soon to be known as Kind of Blue.

The first take began. There was a false start of four seconds, followed by an incomplete take of forty-nine seconds. Townsend interrupted from the booth: something was interfering with the song’s profound hush. “Hold it,” the producer said. “Sorry—listen, we gotta watch it because, ah, there’s noises all the way through this. This is so quiet to begin with, and every click—watch the snare too, we’re picking up some of the vibrations on it—”

Miles, ever on the lookout for meaningful accidentals, demurred. “Well, that goes with it,” he said. “All that goes with it.”

“All right,” Townsend allowed. “Not all the other noises, though . . .”

Another false start, seventeen seconds. An incomplete take, a minute eleven. A telephone rang in the control booth. Once quiet was restored, three more false starts, of sixteen, seven, and fifteen seconds.

Then, history. (...)

The full Take 3 was nine minutes and thirty-five seconds of musical transcendence. Miles’s solo, an impromptu composition in itself, would gain its own immortality: generations of musicians would memorize it note for note. Miles is talking to you in that solo, playing in the middle sonic range of the human voice, and he’s got all kinds of things to say, in brief and at length. He starts and stops; he starts again and goes on. And we’re freshly astonished at how very much he can express, in so few notes, in the moment.

The richness each of the soloists was able to create improvising over just two chords, D and E♭ Dorian, vindicates Miles’s modal concept. Coltrane was in exploratory rather than loud and fast form, traveling up and down each scale to find astringent delights. Cannonball was no less seeking, but lush toned as always, and unable not to find melodies and tuneful fillips, even in this minimalist frame. And Evans’s solo was perhaps most in sync with the tune’s hushed simplicity: playing quiet arpeggios and complex chords a little shyly at first, but then growing more assertive—and surprising: “I’m thinking of the end of Bill’s solo on ‘So What,’” Herbie Hancock told the writer Ashley Kahn. “He plays these phrases, a second apart. He plays seconds.” Still filled with wonderment forty years after the fact, Hancock was talking about an interval on the piano that’s barely an interval—two adjacent keys played simultaneously. By itself, the sound is dissonant; in this context it’s startlingly expressive. “I had never heard anybody do that before,” Hancock said. “He’s following the modal concept maybe more than anybody else. That just opened up a whole vista for me.”(...)

The word “timeless” has become a cliché, a selling tool for luxury goods. And yet Kind of Blue is a timeless album, and “So What” arguably its signature number. What is this about? For sixty years and more, jazz and popular music had consisted of songs that told stories, either explicitly—in lyrics—or in their construction. The most common song framework in both genres was known as AABA: two choruses followed by a bridge (aka channel, release, or middle eight), followed by an out-chorus. (Popular songs of the first half of the twentieth century also typically began with a verse: a brief, explanatory introduction that might or might not be included in performance or on recordings.) The sound of tunes made this way was a satisfying blend of exposition and resolution. (...)

The richness each of the soloists was able to create improvising over just two chords, D and E♭ Dorian, vindicates Miles’s modal concept. Coltrane was in exploratory rather than loud and fast form, traveling up and down each scale to find astringent delights. Cannonball was no less seeking, but lush toned as always, and unable not to find melodies and tuneful fillips, even in this minimalist frame. And Evans’s solo was perhaps most in sync with the tune’s hushed simplicity: playing quiet arpeggios and complex chords a little shyly at first, but then growing more assertive—and surprising: “I’m thinking of the end of Bill’s solo on ‘So What,’” Herbie Hancock told the writer Ashley Kahn. “He plays these phrases, a second apart. He plays seconds.” Still filled with wonderment forty years after the fact, Hancock was talking about an interval on the piano that’s barely an interval—two adjacent keys played simultaneously. By itself, the sound is dissonant; in this context it’s startlingly expressive. “I had never heard anybody do that before,” Hancock said. “He’s following the modal concept maybe more than anybody else. That just opened up a whole vista for me.”(...)

The word “timeless” has become a cliché, a selling tool for luxury goods. And yet Kind of Blue is a timeless album, and “So What” arguably its signature number. What is this about? For sixty years and more, jazz and popular music had consisted of songs that told stories, either explicitly—in lyrics—or in their construction. The most common song framework in both genres was known as AABA: two choruses followed by a bridge (aka channel, release, or middle eight), followed by an out-chorus. (Popular songs of the first half of the twentieth century also typically began with a verse: a brief, explanatory introduction that might or might not be included in performance or on recordings.) The sound of tunes made this way was a satisfying blend of exposition and resolution. (...)

But with Miles, in life and in art, it was always the thing withheld. And the essence of modal music—the essence of “So What”—was that you had no idea how it turned out, or if it turned out. Which was pretty much the way the world was looking at that moment, and maybe the way (you had to think) it was going to look from then on.

by James Kaplan, Esquire | Read more:

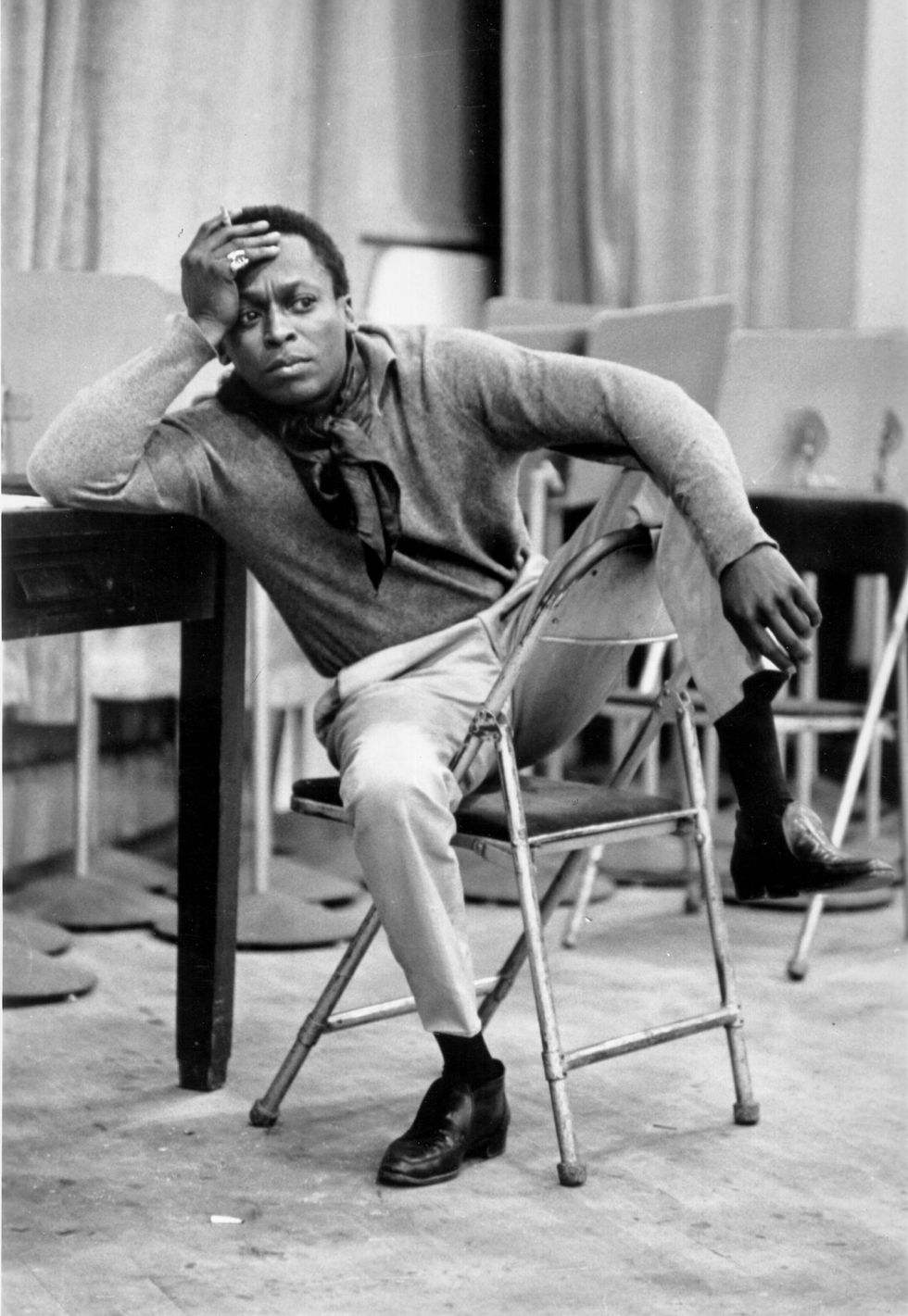

Images: Michael Ochs Archives; David Redfern/Getty Images

Images: Michael Ochs Archives; David Redfern/Getty Images