My father was a brilliant man with many interests. We was a superb craftsman. He made my sister a play-pen for her dolls. He made it from wood, and made it so you could fold it up, just like real playpens. It was, oh, 30 to 36 inches square when opened up. The real marvel was that he’d cut the letters of the alphabet, and the numerals 0-9, into the slats on the sides. He outlined each letter on the slat. Drilled a hole inside the letter. Put the blade of a coping saw through the hole and then reattached the blade to the saw frame. Then stroke by stroke he sawed out the letter or number. When that was done he used small pieces of sandpaper to finish the edges. But that’s only one of many things he built in his workshop.

He also collected stamps, thousands upon thousands of them. He played golf, a game he loved deeply. He liked music, liked to read, and was a good bridge player.

But when he had his time back, when he didn’t have to go into work five days a week, he filled these blocks of time with solitaire. Not with those other things he had previously reserved for evenings and weekends when he was not working.

In time, over the months and, yes, years, he cut back on the solitaire. He never did much, if any, wood working; the tools in his shop lay dormant. He played more golf and spent more time collecting stamps. The sale of his collection (after he’d died) was a minor event in the stamp-collecting world. He found some guys to play bridge with. And bought some records.

The solitaire never left him. Always the well-worn decks of cards. Hours and hours.

Why?

For one thing, work has you interacting with other people, a circle of people who interact with, day in and day out. When you’re retired, that’s gone, especially if you move away from your place of work. But there’s another problem; it has to do with what I’ve been calling behavioral mode. Work requires and supports a certain ecology of tasks, an economy of attention. You train your mind to it – though you might want to think of breaking a horse to saddle. When the job’s gone, that attention economy is rendered useless. But you’ve devoted so much time to it that you don’t know how else to deploy your behavioral resources.

The rise of retirement coaches (...)

More recently Hannah Seo wrote in Business Insider (December 11, 2024).

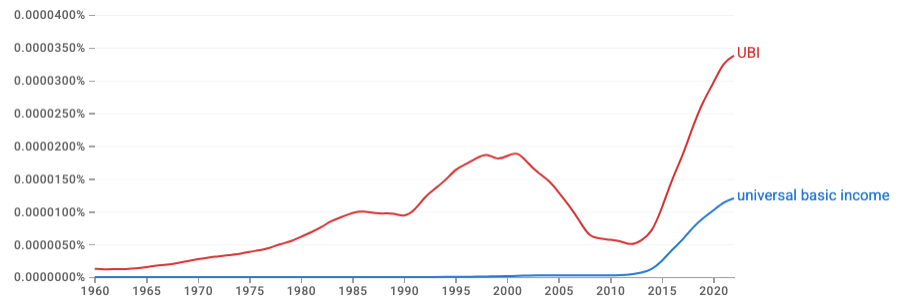

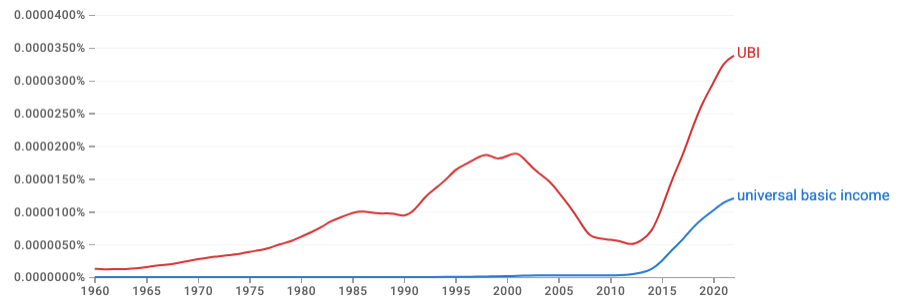

What about universal basic income (UBI), where people without employment are given a no-questions-asked income sufficient to take care of basic needs? As this Google Ngram chart shows, here’s been a lot of interest in it in recent years, especially since 2015:

That’s not going to solve the problem we’ve been discussing. Retirement coaching is not cheap, $75 to $250 an hour. UBI is not going to pay for that. In our present circumstances I fear that UBI is likely to become an indirect subsidy for the drug industry, either legal or illegal. As a culture we are addicted to work. By releasing us from work, I fear that AI will simply place us at the mercy of the worst aspects of that addiction. Will UBI in fact just be an indirect means of subsidizing drug industry, whether legal or illegal?

Keynes Diagnoses the Problem

Back in 1930 John Maynard Keynes saw the problem in his famous essay, “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren.” He predicted that we’d have a 15-hour work week.

Keynes saw the problem clearly:

More recently Hannah Seo wrote in Business Insider (December 11, 2024).

Dee Cascio, a counselor and retirement coach in Sterling, Virginia, says the growing urge to work in retirement points to a larger issue: Work fulfills a lot of needs that people don’t know how to get elsewhere, including relationships, learning, identity, direction, stability, and a sense of order. The structure that work provides is hard to move away from, says Cascio, who is 78 and still practicing. “People think that this transition is a piece of cake, and it’s not,” she says. “It can feel like jumping off a cliff.” […]What is going to happen as AI displaces more and more people from productive work? Sure, AI will create new jobs, but we have no reason that new job creation will be able, in the long run, to make up for displacement. For one thing, the new jobs will be quite different in character from the ones made obsolete. People who have lost their jobs to AI will not be able simply to switch into one of these new jobs. Retraining? For some of them, perhaps. But not for all of them?

The idea that our personal worth is determined by how hard we work and how much money we make is deeply embedded in US work culture. This “Protestant work ethic” puts the responsibility of attaining a good quality of life and well-being on the worker — if you don’t have the time or resources for leisure, it’s because you haven’t earned it. […] This pernicious way of thinking prevents people from seeing purpose or value in life that doesn’t involve working for a paycheck.

What about universal basic income (UBI), where people without employment are given a no-questions-asked income sufficient to take care of basic needs? As this Google Ngram chart shows, here’s been a lot of interest in it in recent years, especially since 2015:

That’s not going to solve the problem we’ve been discussing. Retirement coaching is not cheap, $75 to $250 an hour. UBI is not going to pay for that. In our present circumstances I fear that UBI is likely to become an indirect subsidy for the drug industry, either legal or illegal. As a culture we are addicted to work. By releasing us from work, I fear that AI will simply place us at the mercy of the worst aspects of that addiction. Will UBI in fact just be an indirect means of subsidizing drug industry, whether legal or illegal?

Keynes Diagnoses the Problem

Back in 1930 John Maynard Keynes saw the problem in his famous essay, “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren.” He predicted that we’d have a 15-hour work week.

For many ages to come the old Adam will be so strong in us that everybody will need to do some work if he is to be contented. We shall do more things for ourselves than is usual with the rich today, only too glad to have small duties and tasks and routines. But beyond this, we shall endeavour to spread the bread thin on the butter-to make what work there is still to be done to be as widely shared as possible. Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!We’re nowhere close to that. Families where both adults have jobs are common, with one or both often working more than 40 hours a week. And yet they can’t make ends meet. And while AI holds out the possibility of changing that, perhaps in the mid-term, certainly in the long term, we’re not ready for it.

Keynes saw the problem clearly:

Yet there is no country and no people, I think, who can look forward to the age of leisure and of abundance without a dread. For we have been trained too long to strive and not to enjoy. It is a fearful problem for the ordinary person, with no special talents, to occupy himself, especially if he no longer has roots in the soil or in custom or in the beloved conventions of a traditional society.The real challenge that AI presents to us, I believe is thus a challenge to our values. We live in a society organized to fit the needs of Homo economicus, economic man. Our best chance, perhaps our only chance, of realizing the value of AI and of reaping its economic benefits is to rethink our conception of human nature. Who is doing that? What think tanks have taken it on as their mission? What foundations are supporting the effort and trying to figure out how to turn ideas into social and political practice?

Such is the case today. Social structures and institutions in the developed world are predicated on the centrality of work. Work provides most men and many women with their primary identity, their sense of meaning and self-worth. Without work we are greatly diminished.

by William Benzon, 3 Quarks Daily | Read more:

Image: the author/ChatGPT