Wednesday, August 17, 2011

Decision Fatigue

by John Tierney

Three men doing time in Israeli prisons recently appeared before a parole board consisting of a judge, a criminologist and a social worker. The three prisoners had completed at least two-thirds of their sentences, but the parole board granted freedom to only one of them. Guess which one:

Case 2 (heard at 3:10 p.m.): A Jewish Israeli serving a 16-month sentence for assault.

Case 3 (heard at 4:25 p.m.): An Arab Israeli serving a 30-month sentence for fraud.

There was a pattern to the parole board’s decisions, but it wasn’t related to the men’s ethnic backgrounds, crimes or sentences. It was all about timing, as researchers discovered by analyzing more than 1,100 decisions over the course of a year. Judges, who would hear the prisoners’ appeals and then get advice from the other members of the board, approved parole in about a third of the cases, but the probability of being paroled fluctuated wildly throughout the day. Prisoners who appeared early in the morning received parole about 70 percent of the time, while those who appeared late in the day were paroled less than 10 percent of the time.

The odds favored the prisoner who appeared at 8:50 a.m. — and he did in fact receive parole. But even though the other Arab Israeli prisoner was serving the same sentence for the same crime — fraud — the odds were against him when he appeared (on a different day) at 4:25 in the afternoon. He was denied parole, as was the Jewish Israeli prisoner at 3:10 p.m, whose sentence was shorter than that of the man who was released. They were just asking for parole at the wrong time of day.

There was nothing malicious or even unusual about the judges’ behavior, which was reported earlier this year by Jonathan Levav of Stanford and Shai Danziger of Ben-Gurion University. The judges’ erratic judgment was due to the occupational hazard of being, as George W. Bush once put it, “the decider.” The mental work of ruling on case after case, whatever the individual merits, wore them down. This sort of decision fatigue can make quarterbacks prone to dubious choices late in the game and C.F.O.’s prone to disastrous dalliances late in the evening. It routinely warps the judgment of everyone, executive and nonexecutive, rich and poor — in fact, it can take a special toll on the poor. Yet few people are even aware of it, and researchers are only beginning to understand why it happens and how to counteract it.

Decision fatigue helps explain why ordinarily sensible people get angry at colleagues and families, splurge on clothes, buy junk food at the supermarket and can’t resist the dealer’s offer to rustproof their new car. No matter how rational and high-minded you try to be, you can’t make decision after decision without paying a biological price. It’s different from ordinary physical fatigue — you’re not consciously aware of being tired — but you’re low on mental energy. The more choices you make throughout the day, the harder each one becomes for your brain, and eventually it looks for shortcuts, usually in either of two very different ways. One shortcut is to become reckless: to act impulsively instead of expending the energy to first think through the consequences. (Sure, tweet that photo! What could go wrong?) The other shortcut is the ultimate energy saver: do nothing. Instead of agonizing over decisions, avoid any choice. Ducking a decision often creates bigger problems in the long run, but for the moment, it eases the mental strain. You start to resist any change, any potentially risky move — like releasing a prisoner who might commit a crime. So the fatigued judge on a parole board takes the easy way out, and the prisoner keeps doing time.

Decision fatigue is the newest discovery involving a phenomenon called ego depletion, a term coined by the social psychologist Roy F. Baumeister in homage to a Freudian hypothesis. Freud speculated that the self, or ego, depended on mental activities involving the transfer of energy. He was vague about the details, though, and quite wrong about some of them (like his idea that artists “sublimate” sexual energy into their work, which would imply that adultery should be especially rare at artists’ colonies). Freud’s energy model of the self was generally ignored until the end of the century, when Baumeister began studying mental discipline in a series of experiments, first at Case Western and then at Florida State University.

These experiments demonstrated that there is a finite store of mental energy for exerting self-control. When people fended off the temptation to scarf down M&M’s or freshly baked chocolate-chip cookies, they were then less able to resist other temptations. When they forced themselves to remain stoic during a tearjerker movie, afterward they gave up more quickly on lab tasks requiring self-discipline, like working on a geometry puzzle or squeezing a hand-grip exerciser. Willpower turned out to be more than a folk concept or a metaphor. It really was a form of mental energy that could be exhausted. The experiments confirmed the 19th-century notion of willpower being like a muscle that was fatigued with use, a force that could be conserved by avoiding temptation. To study the process of ego depletion, researchers concentrated initially on acts involving self-control — the kind of self-discipline popularly associated with willpower, like resisting a bowl of ice cream. They weren’t concerned with routine decision-making, like choosing between chocolate and vanilla, a mental process that they assumed was quite distinct and much less strenuous. Intuitively, the chocolate-vanilla choice didn’t appear to require willpower.

But then a postdoctoral fellow, Jean Twenge, started working at Baumeister’s laboratory right after planning her wedding. As Twenge studied the results of the lab’s ego-depletion experiments, she remembered how exhausted she felt the evening she and her fiancé went through the ritual of registering for gifts. Did they want plain white china or something with a pattern? Which brand of knives? How many towels? What kind of sheets? Precisely how many threads per square inch?

Read more:

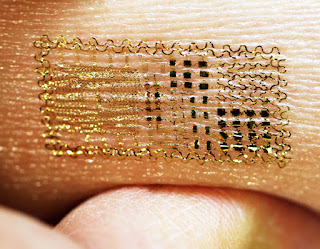

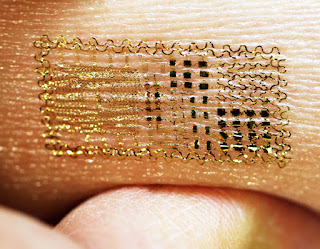

Temporary Tattoos Fitted with Electronics Make Flexible, Ultrathin Sensors

by Kyle Niemeyer

Modern methods of measuring the body's activty, such as electroencephalography (EEG), electrocardiography (ECG), and electromyography (EMG), use electrical signals to measure changes in brain, heart, and muscle activity, respectively. Unfortunately, they rely on bulky and uncomfortable electrodes that are mounted using adhesive tape and conductive gel—or even needles. Because of this, these types of measurements are limited to research and hospital settings and typically used over short periods of time because the contacts can irritate skin.

These limitations may be at an end, however. New research published in Science describes technology that allows electrical measurements (and other measurements, such as temperature and strain) using ultra-thin polymers with embedded circuit elements. These devices connect to skin without adhesives, are practically unnoticeable, and can even be attached via temporary tattoo.

These limitations may be at an end, however. New research published in Science describes technology that allows electrical measurements (and other measurements, such as temperature and strain) using ultra-thin polymers with embedded circuit elements. These devices connect to skin without adhesives, are practically unnoticeable, and can even be attached via temporary tattoo.

The authors refer to their approach as an "epidermal electronic system" (EES), which is basically a fancy way of saying that the device matches the physical properties of the skin (such as stiffness), and its thickness matches that of skin features (wrinkles, creases, etc.). In fact, it adheres to skin only using van der Waals forces—the forces of attraction between atoms and molecules—so no adhesive material is required. Between the flexibility and the lack of adhesive, you wouldn’t really notice one of these attached.

As demonstrations, the authors used their devices to measure heartbeats on the chest (ECG), muscle contractions in the leg (EMG), and alpha waves through the forehead (EEG). The results were all high quality, comparing well against traditional electrode/conductive gel measurements in the same locations. In addition, the devices continuously captured data for six hours, and the devices could be worn for a full 24 hours without any degradation or skin irritation.

One interesting demonstration that also suggests future applications was the measuring of throat muscle activity during speech. Different words showed distinctive signals, and a computer analysis enabled the authors to recognize the vocabulary being used.

Read more:

Modern methods of measuring the body's activty, such as electroencephalography (EEG), electrocardiography (ECG), and electromyography (EMG), use electrical signals to measure changes in brain, heart, and muscle activity, respectively. Unfortunately, they rely on bulky and uncomfortable electrodes that are mounted using adhesive tape and conductive gel—or even needles. Because of this, these types of measurements are limited to research and hospital settings and typically used over short periods of time because the contacts can irritate skin.

These limitations may be at an end, however. New research published in Science describes technology that allows electrical measurements (and other measurements, such as temperature and strain) using ultra-thin polymers with embedded circuit elements. These devices connect to skin without adhesives, are practically unnoticeable, and can even be attached via temporary tattoo.

These limitations may be at an end, however. New research published in Science describes technology that allows electrical measurements (and other measurements, such as temperature and strain) using ultra-thin polymers with embedded circuit elements. These devices connect to skin without adhesives, are practically unnoticeable, and can even be attached via temporary tattoo.The authors refer to their approach as an "epidermal electronic system" (EES), which is basically a fancy way of saying that the device matches the physical properties of the skin (such as stiffness), and its thickness matches that of skin features (wrinkles, creases, etc.). In fact, it adheres to skin only using van der Waals forces—the forces of attraction between atoms and molecules—so no adhesive material is required. Between the flexibility and the lack of adhesive, you wouldn’t really notice one of these attached.

As demonstrations, the authors used their devices to measure heartbeats on the chest (ECG), muscle contractions in the leg (EMG), and alpha waves through the forehead (EEG). The results were all high quality, comparing well against traditional electrode/conductive gel measurements in the same locations. In addition, the devices continuously captured data for six hours, and the devices could be worn for a full 24 hours without any degradation or skin irritation.

One interesting demonstration that also suggests future applications was the measuring of throat muscle activity during speech. Different words showed distinctive signals, and a computer analysis enabled the authors to recognize the vocabulary being used.

Read more:

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Mad About Metered Billing? They Were in 1886, too.

[ed. Like your cable company? Do you like paying metered rates for internet use and data transfer when cloud computing, streaming Netflix, Spotify and other web-based technologies are amping up broadband requirements for the use of their products? Read this article. The more things change the more they stay the same.]

by Matthew Lasar

Hopping mad about metered billing? Spluttering about tethering restrictions and early termination fees? Raging over data caps? You're not alone. Perhaps you can take some comfort from this editorial in The New York Times:

"The greedy and extortionate nature of the telephone monopoly is notorious. Controlling a means of communication which has now become indispensable to the business and social life of the country, the company takes advantage of the public's need to force from it every year an extortionate tribute".Yes, that's how The Times saw it—in 1886. And the newspaper's readers applauded these words. But reading Richard R. John's wonderful book, Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications, one is struck by the contrasts between then and now. The issues are often recognizable; the players a little less so.

Nothing whatever

It was 1887, and Charles M. Fay, General Manager of the Chicago Telephone Exchange, had had about as much as he could take. The pseudo populist legislatures that kowtowed to telephone subscriber groups were on a rampage, Fay warned in a lengthy screed that appeared in the National Telephone Exchange Association's annual journal. Now they were demanding rate caps and price regulation—but for whom?

The poor and working class have "nothing whatever" to do with the telephone, and never will, Fay insisted. "Telephone users are men whose business is so extended and whose time is so valuable as to demand rapid and universal communication," he continued, leaving to posterity this remarkable claim about the service:

"A laborer who goes to work with his dinner basket has no occasion to telephone home that he will be late to dinner; the small householder, whose grocer lives just around corner, would not pay once cent for a telephone wherewith to reach him; the villager, whose deliberate pace is never hurried, will walk every time the few steps necessary to see his neighbor in order to save a nickel. The telephone, like the telegraph, post office and the railroad, is only upon extraordinary occasions used or needed by the poor. It is demanded, and daily depended upon, and should be liberally paid for by the capitalist, mercantile, and manufacturing classes."To be fair, Fay was right about the immediate moment. Given 1887 telephone subscription rates, hardly any workers or villagers bought regular telephone service. They couldn't afford it. But the Bell System's big problem in 1887 wasn't the poor and struggling masses. It was those "mercantile and manufacturing" types—also up in arms at Bell franchise prices.

Appalled at schemes like "measured service" for billing consumers for local calls, telephone subscribers launched municipal and state-wide reform campaigns, backed independent network providers, and ran "rate strikes" on more than one occasion.

"Telephomania," Fay bitterly called the phenomenon—the "only fit word" to describe these ingrates. But their largely forgotten uprisings made a difference.

"By demonstrating the vulnerability of operating companies to legislative intervention," writes John, "they goaded a new generation of telephone managers into providing telephone service to thousands of potential telephone users whom their predecessors had ignored. The popularization of the telephone was the result."

Read more:

Righthaven Rocked, Owes $34,000 After "Fair Use" Loss

[ed. If you're not familiar with Righthaven click on the link below, or the "Interesting Article" link on the sidebar to this blog.]

by Nate Anderson

The wheels appear to be coming off the Righthaven trainwreck-in-progress. The litigation outfit, which generally sues small-time bloggers, forum operators, and the occasional Ars Technica writer, has just been slapped with a $34,000 bill for legal fees.

Righthaven v. Hoehn, filed in Nevada federal court, has been an utterly shambolic piece of litigation. Righthaven sued one Wayne Hoehn, a longtime forum poster on the site Madjack Sports. Buried in Home>>Forums>>Other Stuff>>Politics and Religion, Hoehn made a post under the username "Dogs That Bark" in which he pasted in two op-ed pieces. One came from the Las Vegas Review-Journal, which helped set up the Righthaven operation. Righthaven sued.

This was the salvation of the news business? Targeting forum posters in political subforums of sports handicapping sites? But at least it looked like Righthaven had a point; copying had certainly occurred. Had infringement?

Before it was all over, the judge decided that Righthaven had no standing even to bring the case, since only a copyright holder can file an infringement suit (Righthaven's contract only gave it a bare right to sue… which is no right at all). Then the irritated judge decided that Hoehn's cut-and-paste job was fair use, helping establish a precedent that could undercut the entire Righthaven approach.

Then the defense lawyers wanted to be paid. They asked for $34,000 in fees, arguing that they had won the case. To avoid paying the opposing lawyers, Righthaven recently argued that fees could not be awarded; since Righthaven had no standing to sue in the first place, it argued, the court had no jurisdiction over the case at all, not even to assign legal fees.

Defense attorney Marc J. Randazza was furious. "Righthaven deserves some credit for taking this position, as it requires an amazing amount of chutzpah," he wrote to the judge. "Righthaven seeks a ruling holding that, as long as a plaintiff’s case is completely frivolous, then the court is deprived of the right to make the frivolously sued defendant whole, whereas a partially frivolous case might give rise to fee liability. Righthaven’s view, aside from being bizarre, does not even comport with the law surrounding prudential standing."

The judge agreed. In a terse order today, he decided that Hoehn had won the case (as the "prevailing party") and "the attorney’s fees and costs sought on his behalf are reasonable." Righthaven has until September 14 to cut a check for $34,045.50.

Read more: here and here

by Nate Anderson

The wheels appear to be coming off the Righthaven trainwreck-in-progress. The litigation outfit, which generally sues small-time bloggers, forum operators, and the occasional Ars Technica writer, has just been slapped with a $34,000 bill for legal fees.

Righthaven v. Hoehn, filed in Nevada federal court, has been an utterly shambolic piece of litigation. Righthaven sued one Wayne Hoehn, a longtime forum poster on the site Madjack Sports. Buried in Home>>Forums>>Other Stuff>>Politics and Religion, Hoehn made a post under the username "Dogs That Bark" in which he pasted in two op-ed pieces. One came from the Las Vegas Review-Journal, which helped set up the Righthaven operation. Righthaven sued.

This was the salvation of the news business? Targeting forum posters in political subforums of sports handicapping sites? But at least it looked like Righthaven had a point; copying had certainly occurred. Had infringement?

Before it was all over, the judge decided that Righthaven had no standing even to bring the case, since only a copyright holder can file an infringement suit (Righthaven's contract only gave it a bare right to sue… which is no right at all). Then the irritated judge decided that Hoehn's cut-and-paste job was fair use, helping establish a precedent that could undercut the entire Righthaven approach.

Then the defense lawyers wanted to be paid. They asked for $34,000 in fees, arguing that they had won the case. To avoid paying the opposing lawyers, Righthaven recently argued that fees could not be awarded; since Righthaven had no standing to sue in the first place, it argued, the court had no jurisdiction over the case at all, not even to assign legal fees.

Defense attorney Marc J. Randazza was furious. "Righthaven deserves some credit for taking this position, as it requires an amazing amount of chutzpah," he wrote to the judge. "Righthaven seeks a ruling holding that, as long as a plaintiff’s case is completely frivolous, then the court is deprived of the right to make the frivolously sued defendant whole, whereas a partially frivolous case might give rise to fee liability. Righthaven’s view, aside from being bizarre, does not even comport with the law surrounding prudential standing."

The judge agreed. In a terse order today, he decided that Hoehn had won the case (as the "prevailing party") and "the attorney’s fees and costs sought on his behalf are reasonable." Righthaven has until September 14 to cut a check for $34,045.50.

Read more: here and here

USENIX 2011 Keynote: Network Security in the Medium Term, 2061-2561 AD

[ed. Fascinating speech about where we might go as a society: technologically, economically, socially and culturally. Along with great historical insights.]

by Charlie Stross

Good afternoon, and thank you for inviting me to speak at USENIX Security.by Charlie Stross

Unlike you, I am not a security professional. However, we probably share a common human trait, namely that none of us enjoy looking like a fool in front of a large audience. I therefore chose the title of my talk to minimize the risk of ridicule: if we should meet up in 2061, much less in the 26th century, you’re welcome to rib me about this talk. Because I’ll be happy to still be alive to rib.

So what follows should be seen as a farrago of speculation by a guy who earns his living telling entertaining lies for money.

The question I’m going to spin entertaining lies around is this: what is network security going to be about once we get past the current sigmoid curve of accelerating progress and into a steady state, when Moore’s first law is long since burned out, and networked computing appliances have been around for as long as steam engines?

I’d like to start by making a few basic assumptions about the future, some implicit and some explicit: if only to narrow the field.

For starters, it’s not impossible that we’ll render ourselves extinct through warfare, be wiped out by a gamma ray burster or other cosmological sick joke, or experience the economic equivalent of a kernel panic – an unrecoverable global error in our technosphere. Any of these could happen at some point in the next five and a half centuries: survival is not assured. However, I’m going to spend the next hour assuming that this doesn’t happen – otherwise there’s nothing much for me to talk about.

The idea of an AI singularity has become common currency in SF over the past two decades – that we will create human-equivalent general artificial intelligences, and they will proceed to bootstrap themselves to ever-higher levels of nerdish god-hood, and either keep us as pets or turn us into brightly coloured machine parts. I’m going to palm this card because it’s not immediately obvious that I can say anything useful about a civilization run by beings vastly more intelligent than us. I’d be like an australopithecine trying to visualize daytime cable TV. More to the point, the whole idea of artificial general intelligence strikes me as being as questionable as 19th century fantasies about steam-powered tin men. I do expect us to develop some eerily purposeful software agents over the next decades, tools that can accomplish human-like behavioural patterns better than most humans can, but all that’s going to happen is that those behaviours are going to be reclassified as basically unintelligent, like playing chess or Jeopardy.

In addition to all this Grinch-dom, I’m going to ignore a whole grab-bag of toys from science fiction’s toolbox. It may be fun in fiction, but if you start trying to visualize a coherent future that includes aliens, telepathy, faster than light travel, or time machines, your futurology is going to rapidly run off the road and go crashing around in the blank bits of the map that say HERE BE DRAGONS. This is non-constructive. You can’t look for ways to harden systems against threats that emerge from the existence of Leprechauns or Martians or invisible pink unicorns. So, no Hollywood movie scenarios need apply.

Having said which, I cheerfully predict that at least one barkingly implausible innovation will come along between now and 2061 and turn everything we do upside down, just as the internet has pretty much invalidated any survey of the future of computer security that might have been carried out in 1961.

So what do I expect the world of 2061 to look like?

I am going to explicitly assume that we muddle through our current energy crises, re-tooling for a carbon-neutral economy based on a mixture of power sources. My crystal ball is currently predicting that base load electricity will come from a mix of advanced nuclear fission reactor designs and predictable renewables such as tidal and hydroelectric power. Meanwhile, intermittent renewables such as solar and wind power will be hooked to batteries for load smoothing, used to power up off-grid locations such as much of the (current) developing world, and possibly used on a large scale to produce storable fuels – hydrocarbons via Fischer-Tropsch synthesis, or hydrogen gas vial electrolysis.

We are, I think, going to have molecular nanotechnology and atomic scale integrated circuitry. This doesn’t mean magic nanite pixie-dust a la Star Trek; it means, at a minimum, what today we’d consider to be exotic structural materials. It also means engineered solutions that work a bit like biological systems, but much more efficiently and controllably, and under a much wider range of temperatures and pressures.

Bug Nuggets

by Daniel Fromson

The dining-room table was set with roses and silver candlesticks. At one end, near a grandfather clock, sat two plates of mealworm fried rice. “So, a small lunch,” said my host, Marian Peters. “Freshly prepared.” The inch-long larvae, flavored with garlic and soy sauce, reminded me in texture of delicate, nutty seedpods. “Mealworm is one of my favorites at the moment,” Peters told me, speaking of the larvae of the darkling beetle (Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus). When they’re fresh, she added, their exoskeletons don’t get stuck in your teeth.

Based near Amsterdam, Peters’s company, Bugs Originals, has put freeze-dried locusts and mealworms on the shelves at the 24 outlets of Sligro, the Dutch food wholesaler. It has also developed pesto-flavored “bugsnuggets” and chocolate-dipped “bugslibars”—chicken nuggets and muesli bars, respectively, infused with ground-up mealworms. Both, like Peters’s chicken-mealworm meatballs, await approval for sale across the European Union.

Based near Amsterdam, Peters’s company, Bugs Originals, has put freeze-dried locusts and mealworms on the shelves at the 24 outlets of Sligro, the Dutch food wholesaler. It has also developed pesto-flavored “bugsnuggets” and chocolate-dipped “bugslibars”—chicken nuggets and muesli bars, respectively, infused with ground-up mealworms. Both, like Peters’s chicken-mealworm meatballs, await approval for sale across the European Union.

The company’s goal is to get consumers to embrace bugs as an eco-friendly alternative to conventional meat. With worldwide demand for meat expected to nearly double by 2050, farm-raised crickets, locusts, and mealworms could provide comparable nutrition while using fewer natural resources than poultry or livestock. Crickets, for example, convert feed to body mass about twice as efficiently as pigs and five times as efficiently as cattle. Insects require less land and water—and measured per kilogram of edible mass, mealworms generate 10 to 100 times less greenhouse gas than pigs.

The Netherlands, already one of the world’s top exporters of agricultural products, hopes to lead the world in the production of what environmentalists call “sustainable food,” and the area around the small town of Wageningen, nicknamed “Food Valley,” has one of the world’s highest concentrations of food scientists. It is also home to a tropical entomologist named Arnold van Huis. In the lineup of head shots near the entrance of Wageningen University’s gleaming new entomology department, he’s the guy with a locust jutting from a corner of his lips. Van Huis has been lecturing on the merits of insect-eating, officially known as entomophagy, since 1996. “People have to know that it is safe,” van Huis told me as we sat in his office. “They have to get the idea that it is not wrong.”

Read more:

The dining-room table was set with roses and silver candlesticks. At one end, near a grandfather clock, sat two plates of mealworm fried rice. “So, a small lunch,” said my host, Marian Peters. “Freshly prepared.” The inch-long larvae, flavored with garlic and soy sauce, reminded me in texture of delicate, nutty seedpods. “Mealworm is one of my favorites at the moment,” Peters told me, speaking of the larvae of the darkling beetle (Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus). When they’re fresh, she added, their exoskeletons don’t get stuck in your teeth.

Based near Amsterdam, Peters’s company, Bugs Originals, has put freeze-dried locusts and mealworms on the shelves at the 24 outlets of Sligro, the Dutch food wholesaler. It has also developed pesto-flavored “bugsnuggets” and chocolate-dipped “bugslibars”—chicken nuggets and muesli bars, respectively, infused with ground-up mealworms. Both, like Peters’s chicken-mealworm meatballs, await approval for sale across the European Union.

Based near Amsterdam, Peters’s company, Bugs Originals, has put freeze-dried locusts and mealworms on the shelves at the 24 outlets of Sligro, the Dutch food wholesaler. It has also developed pesto-flavored “bugsnuggets” and chocolate-dipped “bugslibars”—chicken nuggets and muesli bars, respectively, infused with ground-up mealworms. Both, like Peters’s chicken-mealworm meatballs, await approval for sale across the European Union. The company’s goal is to get consumers to embrace bugs as an eco-friendly alternative to conventional meat. With worldwide demand for meat expected to nearly double by 2050, farm-raised crickets, locusts, and mealworms could provide comparable nutrition while using fewer natural resources than poultry or livestock. Crickets, for example, convert feed to body mass about twice as efficiently as pigs and five times as efficiently as cattle. Insects require less land and water—and measured per kilogram of edible mass, mealworms generate 10 to 100 times less greenhouse gas than pigs.

The Netherlands, already one of the world’s top exporters of agricultural products, hopes to lead the world in the production of what environmentalists call “sustainable food,” and the area around the small town of Wageningen, nicknamed “Food Valley,” has one of the world’s highest concentrations of food scientists. It is also home to a tropical entomologist named Arnold van Huis. In the lineup of head shots near the entrance of Wageningen University’s gleaming new entomology department, he’s the guy with a locust jutting from a corner of his lips. Van Huis has been lecturing on the merits of insect-eating, officially known as entomophagy, since 1996. “People have to know that it is safe,” van Huis told me as we sat in his office. “They have to get the idea that it is not wrong.”

Read more:

Virtual and Artificial

by John Markoff

A free online course at Stanford University on artificial intelligence, to be taught this fall by two leading experts from Silicon Valley, has attracted more than 58,000 students around the globe — a class nearly four times the size of Stanford’s entire student body.

The course is one of three being offered experimentally by the Stanford computer science department to extend technology knowledge and skills beyond this elite campus to the entire world, the university is announcing on Tuesday.

The course is one of three being offered experimentally by the Stanford computer science department to extend technology knowledge and skills beyond this elite campus to the entire world, the university is announcing on Tuesday.

The online students will not get Stanford grades or credit, but they will be ranked in comparison to the work of other online students and will receive a “statement of accomplishment.”

For the artificial intelligence course, students may need some higher math, like linear algebra and probability theory, but there are no restrictions to online participation. So far, the age range is from high school to retirees, and the course has attracted interest from more than 175 countries.

The instructors are Sebastian Thrun and Peter Norvig, two of the world’s best-known artificial intelligence experts. In 2005 Dr. Thrun led a team of Stanford students and professors in building a robotic car that won a Pentagon-sponsored challenge by driving 132 miles over unpaved roads in a California desert. More recently he has led a secret Google project to develop autonomous vehicles that have driven more than 100,000 miles on California public roads.

Dr. Norvig is a former NASA scientist who is now Google’s director of research and the author of a leading textbook on artificial intelligence.

The computer scientists said they were uncertain about why the A.I. class had drawn such a large audience. Dr. Thrun said he had tried to advertise the course this summer by distributing notices at an academic conference in Spain, but had gotten only 80 registrants.

Then, several weeks ago he e-mailed an announcement to Carol Hamilton, the executive director of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence. She forwarded the e-mail widely, and the announcement spread virally.

The two scientists said they had been inspired by the recent work of Salman Khan, an M.I.T.-educated electrical engineer who in 2006 established a nonprofit organization to provide video tutorials to students around the world on a variety of subjects via YouTube.

“The vision is: change the world by bringing education to places that can’t be reached today,” said Dr. Thrun.

The rapid increase in the availability of high-bandwidth Internet service, coupled with a wide array of interactive software, has touched off a new wave of experimentation in education.

Read more:

A free online course at Stanford University on artificial intelligence, to be taught this fall by two leading experts from Silicon Valley, has attracted more than 58,000 students around the globe — a class nearly four times the size of Stanford’s entire student body.

The course is one of three being offered experimentally by the Stanford computer science department to extend technology knowledge and skills beyond this elite campus to the entire world, the university is announcing on Tuesday.

The course is one of three being offered experimentally by the Stanford computer science department to extend technology knowledge and skills beyond this elite campus to the entire world, the university is announcing on Tuesday. The online students will not get Stanford grades or credit, but they will be ranked in comparison to the work of other online students and will receive a “statement of accomplishment.”

For the artificial intelligence course, students may need some higher math, like linear algebra and probability theory, but there are no restrictions to online participation. So far, the age range is from high school to retirees, and the course has attracted interest from more than 175 countries.

The instructors are Sebastian Thrun and Peter Norvig, two of the world’s best-known artificial intelligence experts. In 2005 Dr. Thrun led a team of Stanford students and professors in building a robotic car that won a Pentagon-sponsored challenge by driving 132 miles over unpaved roads in a California desert. More recently he has led a secret Google project to develop autonomous vehicles that have driven more than 100,000 miles on California public roads.

Dr. Norvig is a former NASA scientist who is now Google’s director of research and the author of a leading textbook on artificial intelligence.

The computer scientists said they were uncertain about why the A.I. class had drawn such a large audience. Dr. Thrun said he had tried to advertise the course this summer by distributing notices at an academic conference in Spain, but had gotten only 80 registrants.

Then, several weeks ago he e-mailed an announcement to Carol Hamilton, the executive director of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence. She forwarded the e-mail widely, and the announcement spread virally.

The two scientists said they had been inspired by the recent work of Salman Khan, an M.I.T.-educated electrical engineer who in 2006 established a nonprofit organization to provide video tutorials to students around the world on a variety of subjects via YouTube.

“The vision is: change the world by bringing education to places that can’t be reached today,” said Dr. Thrun.

The rapid increase in the availability of high-bandwidth Internet service, coupled with a wide array of interactive software, has touched off a new wave of experimentation in education.

Read more:

Cancer’s Secrets Come Into Sharper Focus

Bryce Vickmark

For the last decade cancer research has been guided by a common vision of how a single cell, outcompeting its neighbors, evolves into a malignant tumor.

Through a series of random mutations, genes that encourage cellular division are pushed into overdrive, while genes that normally send growth-restraining signals are taken offline.

Through a series of random mutations, genes that encourage cellular division are pushed into overdrive, while genes that normally send growth-restraining signals are taken offline.

With the accelerator floored and the brake lines cut, the cell and its progeny are free to rapidly multiply. More mutations accumulate, allowing the cancer cells to elude other safeguards and to invade neighboring tissue and metastasize.

These basic principles — laid out 11 years ago in a landmark paper, “The Hallmarks of Cancer,” by Douglas Hanahan and Robert A. Weinberg, and revisited in a follow-up article this year — still serve as the reigning paradigm, a kind of Big Bang theory for the field.

But recent discoveries have been complicating the picture with tangles of new detail. Cancer appears to be even more willful and calculating than previously imagined.

Most DNA, for example, was long considered junk — a netherworld of detritus that had no important role in cancer or anything else. Only about 2 percent of the human genome carries the code for making enzymes and other proteins, the cogs and scaffolding of the machinery that a cancer cell turns to its own devices.

These days “junk” DNA is referred to more respectfully as “noncoding” DNA, and researchers are finding clues that “pseudogenes” lurking within this dark region may play a role in cancer.

“We’ve been obsessively focusing our attention on 2 percent of the genome,” said Dr. Pier Paolo Pandolfi, a professor of medicine and pathology at Harvard Medical School. This spring, at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research in Orlando, Fla., he described a new “biological dimension” in which signals coming from both regions of the genome participate in the delicate balance between normal cellular behavior and malignancy.

As they look beyond the genome, cancer researchers are also awakening to the fact that some 90 percent of the protein-encoding cells in our body are microbes. We evolved with them in a symbiotic relationship, which raises the question of just who is occupying whom.

“We are massively outnumbered,” said Jeremy K. Nicholson, chairman of biological chemistry and head of the department of surgery and cancer at Imperial College London. Altogether, he said, 99 percent of the functional genes in the body are microbial.

In Orlando, he and other researchers described how genes in this microbiome — exchanging messages with genes inside human cells — may be involved with cancers of the colon, stomach, esophagus and other organs.

These shifts in perspective, occurring throughout cellular biology, can seem as dizzying as what happened in cosmology with the discovery that dark matter and dark energy make up most of the universe: Background suddenly becomes foreground and issues once thought settled are up in the air. In cosmology the Big Bang theory emerged from the confusion in a stronger but more convoluted form. The same may be happening with the science of cancer.

Read more:

For the last decade cancer research has been guided by a common vision of how a single cell, outcompeting its neighbors, evolves into a malignant tumor.

Through a series of random mutations, genes that encourage cellular division are pushed into overdrive, while genes that normally send growth-restraining signals are taken offline.

Through a series of random mutations, genes that encourage cellular division are pushed into overdrive, while genes that normally send growth-restraining signals are taken offline. With the accelerator floored and the brake lines cut, the cell and its progeny are free to rapidly multiply. More mutations accumulate, allowing the cancer cells to elude other safeguards and to invade neighboring tissue and metastasize.

These basic principles — laid out 11 years ago in a landmark paper, “The Hallmarks of Cancer,” by Douglas Hanahan and Robert A. Weinberg, and revisited in a follow-up article this year — still serve as the reigning paradigm, a kind of Big Bang theory for the field.

But recent discoveries have been complicating the picture with tangles of new detail. Cancer appears to be even more willful and calculating than previously imagined.

Most DNA, for example, was long considered junk — a netherworld of detritus that had no important role in cancer or anything else. Only about 2 percent of the human genome carries the code for making enzymes and other proteins, the cogs and scaffolding of the machinery that a cancer cell turns to its own devices.

These days “junk” DNA is referred to more respectfully as “noncoding” DNA, and researchers are finding clues that “pseudogenes” lurking within this dark region may play a role in cancer.

“We’ve been obsessively focusing our attention on 2 percent of the genome,” said Dr. Pier Paolo Pandolfi, a professor of medicine and pathology at Harvard Medical School. This spring, at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research in Orlando, Fla., he described a new “biological dimension” in which signals coming from both regions of the genome participate in the delicate balance between normal cellular behavior and malignancy.

As they look beyond the genome, cancer researchers are also awakening to the fact that some 90 percent of the protein-encoding cells in our body are microbes. We evolved with them in a symbiotic relationship, which raises the question of just who is occupying whom.

“We are massively outnumbered,” said Jeremy K. Nicholson, chairman of biological chemistry and head of the department of surgery and cancer at Imperial College London. Altogether, he said, 99 percent of the functional genes in the body are microbial.

In Orlando, he and other researchers described how genes in this microbiome — exchanging messages with genes inside human cells — may be involved with cancers of the colon, stomach, esophagus and other organs.

These shifts in perspective, occurring throughout cellular biology, can seem as dizzying as what happened in cosmology with the discovery that dark matter and dark energy make up most of the universe: Background suddenly becomes foreground and issues once thought settled are up in the air. In cosmology the Big Bang theory emerged from the confusion in a stronger but more convoluted form. The same may be happening with the science of cancer.

Read more:

Monday, August 15, 2011

Anyone's Guess

by Nancy A. Youssef

When congressional cost-cutters meet later this year to decide on trimming the federal budget, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq could represent juicy targets. But how much do the wars actually cost the U.S. taxpayer?

Nobody really knows.

Yes, Congress has allotted $1.3 trillion for war spending through fiscal year 2011 just to the Defense Department. There are long Pentagon spreadsheets that outline how much of that was spent on personnel, transportation, fuel and other costs. In a recent speech, President Barack Obama assigned the wars a $1 trillion price tag.

But all those numbers are incomplete. Besides what Congress appropriated, the Pentagon spent an additional unknown amount from its $5.2 trillion base budget over that same period. According to a recent Brown University study, the wars and their ripple effects have cost the United States $3.7 trillion, or more than $12,000 per American.

Lawmakers remain sharply divided over the wisdom of slashing the military budget, even with the United States winding down two long conflicts, but there's also a more fundamental problem: It's almost impossible to pin down just what the U.S. military spends on war.

To be sure, the costs are staggering.

According to Defense Department figures, by the end of April the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan — including everything from personnel and equipment to training Iraqi and Afghan security forces and deploying intelligence-gathering drones — had cost an average of $9.7 billion a month, with roughly two-thirds going to Afghanistan. That total is roughly the entire annual budget for the Environmental Protection Agency.

To compare, it would take the State Department — with its annual budget of $27.4 billion — more than four months to spend that amount. NASA could have launched its final shuttle mission in July, which cost $1.5 billion, six times for what the Pentagon is allotted to spend each month in those two wars.

What about Medicare Part D, President George W. Bush's 2003 expansion of prescription drug benefits for seniors, which cost a Congressional Budget Office-estimated $385 billion over 10 years? The Pentagon spends that in Iraq and Afghanistan in about 40 months.

Because of the complex and often ambiguous Pentagon budgeting process, it's nearly impossible to get an accurate breakdown of every operating cost. Some funding comes out of the base budget; other money comes from supplemental appropriations.

But the estimates can be eye-popping, especially considering the logistical challenges to getting even the most basic equipment and comforts to troops in extremely forbidding terrain.

When congressional cost-cutters meet later this year to decide on trimming the federal budget, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq could represent juicy targets. But how much do the wars actually cost the U.S. taxpayer?

Nobody really knows.

Yes, Congress has allotted $1.3 trillion for war spending through fiscal year 2011 just to the Defense Department. There are long Pentagon spreadsheets that outline how much of that was spent on personnel, transportation, fuel and other costs. In a recent speech, President Barack Obama assigned the wars a $1 trillion price tag.

But all those numbers are incomplete. Besides what Congress appropriated, the Pentagon spent an additional unknown amount from its $5.2 trillion base budget over that same period. According to a recent Brown University study, the wars and their ripple effects have cost the United States $3.7 trillion, or more than $12,000 per American.

Lawmakers remain sharply divided over the wisdom of slashing the military budget, even with the United States winding down two long conflicts, but there's also a more fundamental problem: It's almost impossible to pin down just what the U.S. military spends on war.

To be sure, the costs are staggering.

According to Defense Department figures, by the end of April the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan — including everything from personnel and equipment to training Iraqi and Afghan security forces and deploying intelligence-gathering drones — had cost an average of $9.7 billion a month, with roughly two-thirds going to Afghanistan. That total is roughly the entire annual budget for the Environmental Protection Agency.

To compare, it would take the State Department — with its annual budget of $27.4 billion — more than four months to spend that amount. NASA could have launched its final shuttle mission in July, which cost $1.5 billion, six times for what the Pentagon is allotted to spend each month in those two wars.

What about Medicare Part D, President George W. Bush's 2003 expansion of prescription drug benefits for seniors, which cost a Congressional Budget Office-estimated $385 billion over 10 years? The Pentagon spends that in Iraq and Afghanistan in about 40 months.

Because of the complex and often ambiguous Pentagon budgeting process, it's nearly impossible to get an accurate breakdown of every operating cost. Some funding comes out of the base budget; other money comes from supplemental appropriations.

But the estimates can be eye-popping, especially considering the logistical challenges to getting even the most basic equipment and comforts to troops in extremely forbidding terrain.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)