Saturday, October 15, 2011

In His Shoes

by Guy Trebay

This is the tale of the little stiletto that could, a shoe that in the long-ago days of the luxury-goods boom scampered to the top of a rarefied heap. It was just a handful of years ago that the name of Manolo Blahnik, a 68-year-old London cobbler born in the Canary Islands, was familiar only to hard-core fashion hunters and residents of ZIP code 10021.

This is the tale of the little stiletto that could, a shoe that in the long-ago days of the luxury-goods boom scampered to the top of a rarefied heap. It was just a handful of years ago that the name of Manolo Blahnik, a 68-year-old London cobbler born in the Canary Islands, was familiar only to hard-core fashion hunters and residents of ZIP code 10021.

Then a funny thing happened: “Sex and the City.”

Then a funny thing happened: “Sex and the City.”As man-crazy as the character Carrie Bradshaw was on the long-running series, she was just as obsessive about what Vanity Fair once termed every woman’s favorite phallic symbol, shoes. Lust for footwear seldom featured as a continuing television plot line before the show came along. Yet such was the shoe-mania of the character played by Sarah Jessica Parker that, merely by name-checking Manolo Blahnik, she made his a household name.

One sign of the familiarity American women developed with Blahnik’s classically styled shoes — so comfortable, some claimed, you could wear them to scale Everest — was a 2007 survey by Women’s Wear Daily and the trade journal Footwear News. In it, 37 percent of the 2,000 consumers canvassed about their buying habits conceded that they’d willingly bungee-jump off the Golden Gate Bridge in exchange for a lifetime supply of Manolos.

And if they had, they probably would have met Manolo on the way down.

Soon after the 2007 survey appeared, Mr. Blahnik’s name and label took a style dive, his often kittenish designs supplanted by the more aggressive efforts of a new crop of shoemakers, people like Nicholas Kirkwood, Brian Atwood and Christian Louboutin. (...)

Even among those closely associated with the iconic Blahnik shoe there was a sense that the tide had shifted. A time came, Ms. Parker said, “when Manolo wasn’t defining the aesthetic,” when Blade Runner styles took over from smart patent pumps, and wearing Manolos was almost like announcing one had turned in one’s coquette card and started taking style cues from Judge Judy.

Mr. Blahnik, notoriously indifferent to fashion trends, stayed true to an aesthetic that he said was formed in his 1950s boyhood by women like Audrey Hepburn and the ultra-elegant model Dovima, nee Dorothy Juba. “The gimmicky thing I’m not very keen on,” Mr. Blahnik said last week from London. “I’ve never been tempted to do these hideous furniture shoes.”

But fashion, as we all know, is nothing if not fickle; Heidi Klum is merely reporting fact when she notes each week on “Project Runway” that one day you’re in and the next day you’re out. So it should come as no surprise that, suddenly, signs are everywhere that Blahnik is back in style.

Read more:

photo: Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

R.I.P., the Movie Camera: 1888-2011

by Matt Zoller Seitz

We might as well call it: Cinema as we knew it is dead.

An article at the moviemaking technology website Creative Cow reports that the three major manufacturers of motion picture film cameras — Aaton, ARRI and Panavision — have all ceased production of new cameras within the last year, and will only make digital movie cameras from now on. As the article’s author, Debra Kaufman, poignantly puts it, “Someone, somewhere in the world is now holding the last film camera ever to roll off the line.”

What this means is that, even though purists may continue to shoot movies on film, film itself will may become increasingly hard to come by, use, develop and preserve. It also means that the film camera — invented in 1888 by Louis Augustin Le Prince — will become to cinema what typewriters are to literature. Anybody who still uses a Smith-Corona or IBM Selectric typewriter knows what that means: if your beloved machine breaks, you can’t just take it to the local repair shop, you have to track down some old hermit in another town who advertises on Craigslist and stockpiles spare parts in his basement.

As Aaton founder Jean-Pierre Beauviala told Kaufman: “Almost nobody is buying new film cameras. Why buy a new one when there are so many used cameras around the world? We wouldn’t survive in the film industry if we were not designing a digital camera.” Bill Russell, ARRI’s vice president of cameras, added that: “The demand for film cameras on a global basis has all but disappeared.”

Theaters, movies, moviegoing and other core components of what we once called “cinema” persist, and may endure. But they’re not quite what they were in the analog cinema era. They’re something new, or something else — the next generation of technologies and rituals that had changed shockingly little between 1895 and the early aughts. We knew this day would come. Calling oneself a “film director” or “film editor” or “film buff” or a “film critic” has over the last decade started to seem a faintly nostalgic affectation; decades hence it may start to seem fanciful. It’s a vestigial word that increasingly refers to something that does not actually exist — rather like referring to the mass media as “the press.”

Read more:

***

[ed. A little-known tidbit from Wikipedia:] Until the standardization of the projection speed of 24 frames per second (fps) for sound films between 1926 and 1930, silent films were shot at variable speeds (or "frame rates") anywhere from 12 to 26 fps, depending on the year and studio. "Standard silent film speed" is often said to be 16 fps as a result of the Lumière brothers' Cinematographé, but industry practice varied considerably; there was no actual standard. Cameramen of the era insisted that their cranking technique was exactly 16 fps, but modern examination of the films shows this to be in error, that they often cranked faster. Unless carefully shown at their intended speeds silent films can appear unnaturally fast. However, some scenes were intentionally undercranked during shooting to accelerate the action—particularly for comedies and action films.

Slow projection of a cellulose nitrate base film carried a risk of fire, as each frame was exposed for a longer time to the intense heat of the projection lamp; but there were other reasons to project a film at a greater pace. Often projectionists received general instructions from the distributors on the musical director's cue sheet as to how fast particular reels or scenes should be projected. In rare instances, usually for larger productions, cue sheets specifically for the projectionist provided a detailed guide to presenting the film. Theaters also—to maximize profit—sometimes varied projection speeds depending on the time of day or popularity of a film, and to fit a film into a prescribed time slot.

Low Profile

[ed. Interesting article, more for the insights into U.S./Saudi relations than the man himself. I share Glenn Greenwalds' suspicion that this "plot" has more hidden angles than have been revealed to date.]

by Helene Cooper

For years, Adel al-Jubeir was the playboy Saudi envoy and man about town, hosting parties on the diplomatic circuit, hobnobbing with this city’s political elite and appearing at events with media celebrities like Campbell Brown, then the White House correspondent for NBC News.

Then in 2007, amid tales of palace intrigue and feuding Saudi princes, Mr. Jubeir became the first commoner to be named the Saudi ambassador to the United States. And the youngish-by-Saudi-standards — he was 44 at the time; his predecessor was 61 — envoy for King Abdullah virtually disappeared. From the gossip columns, that is.

The Obama administration’s charge this week that an Iranian-American car salesman backed by Iranian officials hatched a plot to assassinate Mr. Jubeir using a Mexican drug cartel has, by itself, made for riveting reading. But what it has also done is to push the soft-spoken Mr. Jubeir, who had been quietly managing his own reinvention as his king’s most trusted adviser on Saudi-American relations, back into the media glare.

Mr. Jubeir has not been too thrilled with the spotlight. “No, he’s not granting any requests for interviews,” one press aide at the Saudi Embassy said on Thursday. “People keep calling and calling — he doesn’t want to talk.”

Read more:

photo: Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

by Helene Cooper

For years, Adel al-Jubeir was the playboy Saudi envoy and man about town, hosting parties on the diplomatic circuit, hobnobbing with this city’s political elite and appearing at events with media celebrities like Campbell Brown, then the White House correspondent for NBC News.

Then in 2007, amid tales of palace intrigue and feuding Saudi princes, Mr. Jubeir became the first commoner to be named the Saudi ambassador to the United States. And the youngish-by-Saudi-standards — he was 44 at the time; his predecessor was 61 — envoy for King Abdullah virtually disappeared. From the gossip columns, that is.

The Obama administration’s charge this week that an Iranian-American car salesman backed by Iranian officials hatched a plot to assassinate Mr. Jubeir using a Mexican drug cartel has, by itself, made for riveting reading. But what it has also done is to push the soft-spoken Mr. Jubeir, who had been quietly managing his own reinvention as his king’s most trusted adviser on Saudi-American relations, back into the media glare.

Mr. Jubeir has not been too thrilled with the spotlight. “No, he’s not granting any requests for interviews,” one press aide at the Saudi Embassy said on Thursday. “People keep calling and calling — he doesn’t want to talk.”

Read more:

photo: Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

Friday, October 14, 2011

Friday Book Club - Life

[ed. Almost done with this and I have to say, this review is spot on. Who would have thought that Keef (of all people) would have it in him? Wonderful.]

by Michiko Kakutani

Halfway through his electrifying new memoir, “Life,” Keith Richards writes about the consequences of fame: the nearly complete loss of privacy and the weirdness of being mythologized by fans as a sort of folk-hero renegade.

Halfway through his electrifying new memoir, “Life,” Keith Richards writes about the consequences of fame: the nearly complete loss of privacy and the weirdness of being mythologized by fans as a sort of folk-hero renegade.

“I can’t untie the threads of how much I played up to the part that was written for me,” he says. “I mean the skull ring and the broken tooth and the kohl. Is it half and half? I think in a way your persona, your image, as it used to be known, is like a ball and chain. People think I’m still a goddamn junkie. It’s 30 years since I gave up the dope! Image is like a long shadow. Even when the sun goes down, you can see it.”

By turns earnest and wicked, sweet and sarcastic and unsparing, Mr. Richards, now 66, writes with uncommon candor and immediacy. He’s decided that he’s going to tell it as he remembers it, and helped along with notebooks, letters and a diary he once kept, he remembers almost everything. He gives us an indelible, time-capsule feel for the madness that was life on the road with the Stones in the years before and after Altamont; harrowing accounts of his many close shaves and narrow escapes (from the police, prison time, drug hell); and a heap of sharp-edged snapshots of friends and colleagues — most notably, his longtime musical partner and sometime bête noire, Mick Jagger.

But “Life” — which was written with the veteran journalist James Fox — is way more than a revealing showbiz memoir. It is also a high-def, high-velocity portrait of the era when rock ’n’ roll came of age, a raw report from deep inside the counterculture maelstrom of how that music swept like a tsunami over Britain and the United States. It’s an eye-opening all-nighter in the studio with a master craftsman disclosing the alchemical secrets of his art. And it’s the intimate and moving story of one man’s long strange trip over the decades, told in dead-on, visceral prose without any of the pretense, caution or self-consciousness that usually attend great artists sitting for their self-portraits.

Die-hard Stones fans, of course, will pore over the detailed discussions of how songs like “Ruby Tuesday” and “Gimme Shelter” came to be written, the birthing process of some of Mr. Richards’s classic guitar riffs and the collaborative dynamic between him and Mr. Jagger. But the book will also dazzle the uninitiated, who thought they had only a casual interest in the Stones or who thought of Mr. Richards, vaguely, as a rock god who was mad, bad and dangerous to know. The book is that compelling and eloquently told.

Mr. Richards’s prose is like his guitar playing: intense, elemental, utterly distinctive and achingly, emotionally direct. Just as the Stones perfected a signature sound that could accommodate everything from ferocious Dionysian anthems to melancholy ballads about love and time and loss, so Mr. Richards has found a voice in these pages — a kind of rich, primal Keith-Speak — that enables him to dispense funny, streetwise observations, tender family reminiscences, casually profane yarns and wry literary allusions with both heart-felt sincerity and bad-boy charm.

Read more:

photo: Patricia Wall/The New York Times

by Michiko Kakutani

For legions of Rolling Stones fans, Keith Richards is not only the heart and soul of the world’s greatest rock ’n’ roll band, he’s also the very avatar of rebellion: the desperado, the buccaneer, the poète maudit, the soul survivor and main offender, the torn and frayed outlaw, and the coolest dude on the planet, named both No. 1 on the rock stars most-likely-to-die list and the one life form (besides the cockroach) capable of surviving nuclear war.

Halfway through his electrifying new memoir, “Life,” Keith Richards writes about the consequences of fame: the nearly complete loss of privacy and the weirdness of being mythologized by fans as a sort of folk-hero renegade.

Halfway through his electrifying new memoir, “Life,” Keith Richards writes about the consequences of fame: the nearly complete loss of privacy and the weirdness of being mythologized by fans as a sort of folk-hero renegade. “I can’t untie the threads of how much I played up to the part that was written for me,” he says. “I mean the skull ring and the broken tooth and the kohl. Is it half and half? I think in a way your persona, your image, as it used to be known, is like a ball and chain. People think I’m still a goddamn junkie. It’s 30 years since I gave up the dope! Image is like a long shadow. Even when the sun goes down, you can see it.”

By turns earnest and wicked, sweet and sarcastic and unsparing, Mr. Richards, now 66, writes with uncommon candor and immediacy. He’s decided that he’s going to tell it as he remembers it, and helped along with notebooks, letters and a diary he once kept, he remembers almost everything. He gives us an indelible, time-capsule feel for the madness that was life on the road with the Stones in the years before and after Altamont; harrowing accounts of his many close shaves and narrow escapes (from the police, prison time, drug hell); and a heap of sharp-edged snapshots of friends and colleagues — most notably, his longtime musical partner and sometime bête noire, Mick Jagger.

But “Life” — which was written with the veteran journalist James Fox — is way more than a revealing showbiz memoir. It is also a high-def, high-velocity portrait of the era when rock ’n’ roll came of age, a raw report from deep inside the counterculture maelstrom of how that music swept like a tsunami over Britain and the United States. It’s an eye-opening all-nighter in the studio with a master craftsman disclosing the alchemical secrets of his art. And it’s the intimate and moving story of one man’s long strange trip over the decades, told in dead-on, visceral prose without any of the pretense, caution or self-consciousness that usually attend great artists sitting for their self-portraits.

Die-hard Stones fans, of course, will pore over the detailed discussions of how songs like “Ruby Tuesday” and “Gimme Shelter” came to be written, the birthing process of some of Mr. Richards’s classic guitar riffs and the collaborative dynamic between him and Mr. Jagger. But the book will also dazzle the uninitiated, who thought they had only a casual interest in the Stones or who thought of Mr. Richards, vaguely, as a rock god who was mad, bad and dangerous to know. The book is that compelling and eloquently told.

Mr. Richards’s prose is like his guitar playing: intense, elemental, utterly distinctive and achingly, emotionally direct. Just as the Stones perfected a signature sound that could accommodate everything from ferocious Dionysian anthems to melancholy ballads about love and time and loss, so Mr. Richards has found a voice in these pages — a kind of rich, primal Keith-Speak — that enables him to dispense funny, streetwise observations, tender family reminiscences, casually profane yarns and wry literary allusions with both heart-felt sincerity and bad-boy charm.

Read more:

photo: Patricia Wall/The New York Times

(Free) Ticket to Ride

by Akiko Fujita

If you’ve ever wanted to visit Japan, this may be your chance.

In a desperate attempt to lure tourists back to a country plagued by radiation fears and constant earthquakes, the Japan Tourism Agency’s proposed an unprecedented campaign – 10,000 free roundtrip tickets.

The catch is, you need to publicize your trip on blogs and social media sites.

The number of foreign visitors to Japan has dropped drastically, since a catastrophic earthquake and tsunami triggered a nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Dai-ichi Power plant in March. Nearly 20,000 people have been confirmed dead, while more than 80,000 remain displaced because of radiation concerns. In the first three months following the triple disasters, the number of foreign visitors to Japan was cut in half, compared with the same time in 2010. The strong Japanese currency has made matters worse.

The tourism agency says it plans to open a website to solicit applicants interested in the free tickets. Would- be visitors will have to detail in writing their travel plans in Japan, and explain what they hope to get out of the trip. Successful applicants would pay for their own accommodation and meals. They would also be required to write a review their travel experiences, and post it online.

“We are hoping to get highly influential blogger-types, and others who can spread the word that Japan is a safe place to visit,” said Kazuyoshi Sato, with the agency.

The agency has requested more than a billion yen to pay for the tourism blitz. If lawmakers approve the funding, Sato says visitors could begin signing up as early as next April.

via:

Illustration: Katsuyuki Nishijima

If you’ve ever wanted to visit Japan, this may be your chance.

In a desperate attempt to lure tourists back to a country plagued by radiation fears and constant earthquakes, the Japan Tourism Agency’s proposed an unprecedented campaign – 10,000 free roundtrip tickets.

The catch is, you need to publicize your trip on blogs and social media sites.

The number of foreign visitors to Japan has dropped drastically, since a catastrophic earthquake and tsunami triggered a nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Dai-ichi Power plant in March. Nearly 20,000 people have been confirmed dead, while more than 80,000 remain displaced because of radiation concerns. In the first three months following the triple disasters, the number of foreign visitors to Japan was cut in half, compared with the same time in 2010. The strong Japanese currency has made matters worse.

The tourism agency says it plans to open a website to solicit applicants interested in the free tickets. Would- be visitors will have to detail in writing their travel plans in Japan, and explain what they hope to get out of the trip. Successful applicants would pay for their own accommodation and meals. They would also be required to write a review their travel experiences, and post it online.

“We are hoping to get highly influential blogger-types, and others who can spread the word that Japan is a safe place to visit,” said Kazuyoshi Sato, with the agency.

The agency has requested more than a billion yen to pay for the tourism blitz. If lawmakers approve the funding, Sato says visitors could begin signing up as early as next April.

via:

Illustration: Katsuyuki Nishijima

First in Line

by Stan Schroeder

We’re quite sure that Steve Wozniak, the co-founder of Apple, could make a phone call and get an iPhone 4S well before it hits the stores. However, he hasn’t done that. Instead, he’s first in line in front of the Apple Store in Los Gatos, California, waiting for his iPhone 4S.

“The long wait begins. I’m first in line. The guy ahead was on the wrong side and he’s pissed,” tweeted Wozniak as he took his place in front of the store.

Wozniak is known for showing up in lines for new Apple products; he was in line for the iPhone 3GS back in 2009, and again for the iPhone 4 in 2010.

This year, he managed to get first place in line (usually, the crowd insists that he goes up front), and he’s killing time by chatting with other Apple fans and signing their iPhones.

Although he could get the latest versions of Apple products in an easier way, Wozniak claims he likes to stand in line at new product launches. “I want to get mine along with the millions of other fans,” he said to CNN.

via: Mashable

[ed. Plus, an excellent recent interview with Woz, here:]

We’re quite sure that Steve Wozniak, the co-founder of Apple, could make a phone call and get an iPhone 4S well before it hits the stores. However, he hasn’t done that. Instead, he’s first in line in front of the Apple Store in Los Gatos, California, waiting for his iPhone 4S.

“The long wait begins. I’m first in line. The guy ahead was on the wrong side and he’s pissed,” tweeted Wozniak as he took his place in front of the store.

Wozniak is known for showing up in lines for new Apple products; he was in line for the iPhone 3GS back in 2009, and again for the iPhone 4 in 2010.

This year, he managed to get first place in line (usually, the crowd insists that he goes up front), and he’s killing time by chatting with other Apple fans and signing their iPhones.

Although he could get the latest versions of Apple products in an easier way, Wozniak claims he likes to stand in line at new product launches. “I want to get mine along with the millions of other fans,” he said to CNN.

via: Mashable

[ed. Plus, an excellent recent interview with Woz, here:]

Dennis Ritchie: (1941 -2011)

by Cade Metz

The tributes to Dennis Ritchie won’t match the river of praise that spilled out over the web after the death of Steve Jobs. But they should.

And then some.

“When Steve Jobs died last week, there was a huge outcry, and that was very moving and justified. But Dennis had a bigger effect, and the public doesn’t even know who he is,” says Rob Pike, the programming legend and current Googler who spent 20 years working across the hall from Ritchie at the famed Bell Labs.

On Wednesday evening, with a post to Google+, Pike announced that Ritchie had died at his home in New Jersey over the weekend after a long illness, and though the response from hardcore techies was immense, the collective eulogy from the web at large doesn’t quite do justice to Ritchie’s sweeping influence on the modern world. Dennis Ritchie is the father of the C programming language, and with fellow Bell Labs researcher Ken Thompson, he used C to build UNIX, the operating system that so much of the world is built on — including the Apple empire overseen by Steve Jobs.

“Pretty much everything on the web uses those two things: C and UNIX,” Pike tells Wired. “The browsers are written in C. The UNIX kernel — that pretty much the entire Internet runs on — is written in C. Web servers are written in C, and if they’re not, they’re written in Java or C++, which are C derivatives, or Python or Ruby, which are implemented in C. And all of the network hardware running these programs I can almost guarantee were written in C.

“It’s really hard to overstate how much of the modern information economy is built on the work Dennis did.”

Even Windows was once written in C, he adds, and UNIX underpins both Mac OS X, Apple’s desktop operating system, and iOS, which runs the iPhone and the iPad. “Jobs was the king of the visible, and Ritchie is the king of what is largely invisible,” says Martin Rinard, professor of electrical engineering and computer science at MIT and a member of the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.

“Jobs’ genius is that he builds these products that people really like to use because he has taste and can build things that people really find compelling. Ritchie built things that technologists were able to use to build core infrastructure that people don’t necessarily see much anymore, but they use everyday.” (...)

Ritchie’s running joke was that C had “the power of assembly language and the convenience of … assembly language.” In other words, he acknowledged that C was a less-than-gorgeous creation that still ran very close to the hardware. Today, it’s considered a low-level language, not high. But Ritchie’s joke didn’t quite do justice to the new language. In offering true data structures, it operated at a level that was just high enough.

Read more:

photo: Dennis Ritchie (standing) and Ken Thompson at a PDP-11 in 1972. (Courtesy of Bell Labs)

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Haiti Doesn't Need Your Old T-Shirt

by Charles Kenny

The Green Bay Packers this year beat the Pittsburgh Steelers to win Super Bowl XLV in Arlington, Texas. In parts of the developing world, however, an alternate reality exists: "Pittsburgh Steelers: Super Bowl XLV Champions" appears emblazoned on T-shirts from Nicaragua to Zambia. The shirt wearers, of course, are not an international cadre of Steelers die-hards, but recipients of the many thousands of excess shirts the National Football League produced to anticipate the post-game merchandising frenzy. Each year, the NFL donates the losing team's shirts to the charity World Vision, which then ships them off to developing countries to be handed out for free.

Everyone wins, right? The NFL offloads 100,000 shirts (and hats and sweatshirts) that can't be sold -- and takes the donation as a tax break. World Vision gets clothes to distribute at no cost. And some Nicaraguans and Zambians get a free shirt. What's not to like?

Everyone wins, right? The NFL offloads 100,000 shirts (and hats and sweatshirts) that can't be sold -- and takes the donation as a tax break. World Vision gets clothes to distribute at no cost. And some Nicaraguans and Zambians get a free shirt. What's not to like?

Quite a lot, as it happens -- so much so that there's even a Twitter hashtag, #SWEDOW, for "Stuff We Don't Want," to track such developed-world offloading, whether it's knit teddy bears for kids in refugee camps, handmade puppets for orphans, yoga mats for Haiti, or dresses made out of pillowcases for African children. The blog Tales from the Hood, run by an anonymous aid worker, even set up a SWEDOW prize, won by Knickers 4 Africa, a (thankfully now defunct) British NGO set up a couple of years ago to send panties south of the Sahara.

Here's the trouble with dumping stuff we don't want on people in need: What they need is rarely the stuff we don't want. And even when they do need that kind of stuff, there are much better ways for them to get it than for a Western NGO to gather donations at a suburban warehouse, ship everything off to Africa or South America, and then try to distribute it to remote areas. World Vision, for example, spends 58 cents per shirt on shipping, warehousing, and distributing them, according to data reported by the blog Aid Watch -- well within the range of what a secondhand shirt costs in a developing country. Bringing in shirts from outside also hurts the local economy: Garth Frazer of the University of Toronto estimates that increased used-clothing imports accounted for about half of the decline in apparel industry employment in Africa between 1981 and 2000. Want to really help a Zambian? Give him a shirt made in Zambia.

The mother of all swedow is the $2 billion-plus U.S. food aid program, a boondoggle that lingers on only because of the lobbying muscle of agricultural conglomerates. (Perhaps the most embarrassing moment was when the United States airdropped 2.4 million Pop-Tarts on Afghanistan in January 2002.) Harvard University's Nathan Nunn and Yale University's Nancy Qian have shown that the scale of U.S. food aid isn't strongly tied to how much recipient countries actually require it -- but it does rise after a bumper crop in the American heartland, suggesting that food aid is far more about dumping American leftovers than about sending help where help's needed. And just like secondhand clothing, castoff food exports can hurt local economies. Between the 1980s and today, subsidized rice exports from the United States to Haiti wiped out thousands of local farmers and helped reduce the proportion of locally produced rice consumed in the country from 47 to 15 percent. Former President Bill Clinton concluded that the food aid program "may have been good for some of my farmers in Arkansas, but it has not worked.… I had to live every day with the consequences of the lost capacity to produce a rice crop in Haiti to feed those people because of what I did."

Read more:

photo: Leah Missbach Day/World Vision

The Green Bay Packers this year beat the Pittsburgh Steelers to win Super Bowl XLV in Arlington, Texas. In parts of the developing world, however, an alternate reality exists: "Pittsburgh Steelers: Super Bowl XLV Champions" appears emblazoned on T-shirts from Nicaragua to Zambia. The shirt wearers, of course, are not an international cadre of Steelers die-hards, but recipients of the many thousands of excess shirts the National Football League produced to anticipate the post-game merchandising frenzy. Each year, the NFL donates the losing team's shirts to the charity World Vision, which then ships them off to developing countries to be handed out for free.

Everyone wins, right? The NFL offloads 100,000 shirts (and hats and sweatshirts) that can't be sold -- and takes the donation as a tax break. World Vision gets clothes to distribute at no cost. And some Nicaraguans and Zambians get a free shirt. What's not to like?

Everyone wins, right? The NFL offloads 100,000 shirts (and hats and sweatshirts) that can't be sold -- and takes the donation as a tax break. World Vision gets clothes to distribute at no cost. And some Nicaraguans and Zambians get a free shirt. What's not to like? Quite a lot, as it happens -- so much so that there's even a Twitter hashtag, #SWEDOW, for "Stuff We Don't Want," to track such developed-world offloading, whether it's knit teddy bears for kids in refugee camps, handmade puppets for orphans, yoga mats for Haiti, or dresses made out of pillowcases for African children. The blog Tales from the Hood, run by an anonymous aid worker, even set up a SWEDOW prize, won by Knickers 4 Africa, a (thankfully now defunct) British NGO set up a couple of years ago to send panties south of the Sahara.

Here's the trouble with dumping stuff we don't want on people in need: What they need is rarely the stuff we don't want. And even when they do need that kind of stuff, there are much better ways for them to get it than for a Western NGO to gather donations at a suburban warehouse, ship everything off to Africa or South America, and then try to distribute it to remote areas. World Vision, for example, spends 58 cents per shirt on shipping, warehousing, and distributing them, according to data reported by the blog Aid Watch -- well within the range of what a secondhand shirt costs in a developing country. Bringing in shirts from outside also hurts the local economy: Garth Frazer of the University of Toronto estimates that increased used-clothing imports accounted for about half of the decline in apparel industry employment in Africa between 1981 and 2000. Want to really help a Zambian? Give him a shirt made in Zambia.

The mother of all swedow is the $2 billion-plus U.S. food aid program, a boondoggle that lingers on only because of the lobbying muscle of agricultural conglomerates. (Perhaps the most embarrassing moment was when the United States airdropped 2.4 million Pop-Tarts on Afghanistan in January 2002.) Harvard University's Nathan Nunn and Yale University's Nancy Qian have shown that the scale of U.S. food aid isn't strongly tied to how much recipient countries actually require it -- but it does rise after a bumper crop in the American heartland, suggesting that food aid is far more about dumping American leftovers than about sending help where help's needed. And just like secondhand clothing, castoff food exports can hurt local economies. Between the 1980s and today, subsidized rice exports from the United States to Haiti wiped out thousands of local farmers and helped reduce the proportion of locally produced rice consumed in the country from 47 to 15 percent. Former President Bill Clinton concluded that the food aid program "may have been good for some of my farmers in Arkansas, but it has not worked.… I had to live every day with the consequences of the lost capacity to produce a rice crop in Haiti to feed those people because of what I did."

Read more:

photo: Leah Missbach Day/World Vision

Apollo 11 Customs Form

by Tariq Malik,

Before the ticker tape parades and the inevitable world tour, the triumphant Apollo 11 astronauts were greeted with a more mundane aspect of life on Earth when they splashed down 40 years ago today - going through customs.

Just what did Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins have to declare? Moon rocks, moon dust and other lunar samples, according to the customs form filed at the Honolulu Airport in Hawaii on July 24, 1969 - the day the Apollo 11 crew splashed down in the Pacific Ocean to end their historic moon landing mission.

Just what did Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins have to declare? Moon rocks, moon dust and other lunar samples, according to the customs form filed at the Honolulu Airport in Hawaii on July 24, 1969 - the day the Apollo 11 crew splashed down in the Pacific Ocean to end their historic moon landing mission.

The customs form is signed by all three Apollo 11 astronauts. They declared their cargo and listed their flight route as starting Cape Kennedy (now Cape Canaveral) in Florida with a stopover on the moon.

The form was posted to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Web site this week to mark the Apollo 11 mission's 40th anniversary. A copy was obtained by SPACE.com and verified by NASA.

'Yes, it's authentic,' NASA spokesperson John Yembrick told SPACE.com. 'It was a little joke at the time.

'It's more humor than fact because Apollo 11 splashed down 920 miles (1,480 km) southwest of Hawaii and 13 miles (21 km) from the USS Hornet, a Navy ship sent to recover the crew. It took a two more days for the astronauts to actually return to Hawaii on July 26, where they were welcomed with a July 27 ceremony at Pearl Harbor.

Read more:

via:

Before the ticker tape parades and the inevitable world tour, the triumphant Apollo 11 astronauts were greeted with a more mundane aspect of life on Earth when they splashed down 40 years ago today - going through customs.

Just what did Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins have to declare? Moon rocks, moon dust and other lunar samples, according to the customs form filed at the Honolulu Airport in Hawaii on July 24, 1969 - the day the Apollo 11 crew splashed down in the Pacific Ocean to end their historic moon landing mission.

Just what did Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins have to declare? Moon rocks, moon dust and other lunar samples, according to the customs form filed at the Honolulu Airport in Hawaii on July 24, 1969 - the day the Apollo 11 crew splashed down in the Pacific Ocean to end their historic moon landing mission.The customs form is signed by all three Apollo 11 astronauts. They declared their cargo and listed their flight route as starting Cape Kennedy (now Cape Canaveral) in Florida with a stopover on the moon.

The form was posted to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Web site this week to mark the Apollo 11 mission's 40th anniversary. A copy was obtained by SPACE.com and verified by NASA.

'Yes, it's authentic,' NASA spokesperson John Yembrick told SPACE.com. 'It was a little joke at the time.

'It's more humor than fact because Apollo 11 splashed down 920 miles (1,480 km) southwest of Hawaii and 13 miles (21 km) from the USS Hornet, a Navy ship sent to recover the crew. It took a two more days for the astronauts to actually return to Hawaii on July 26, where they were welcomed with a July 27 ceremony at Pearl Harbor.

Read more:

via:

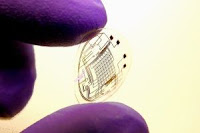

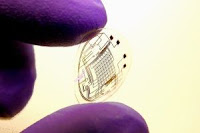

Bionic Contacts

Movie characters from the Terminator to the Bionic Woman use bionic eyes to zoom in on far-off scenes, have useful facts pop into their field of view, or create virtual crosshairs. Off the screen, virtual displays have been proposed for more practical purposes-visual aids to help vision-impaired people, holographic driving control panels and even as a way to surf the Web on the go.

The device to make this happen may be familiar. Engineers at the University of Washington have for the first time used manufacturing techniques at microscopic scales to combine a flexible, biologically safe contact lens with an imprinted electronic circuit and lights.

The device to make this happen may be familiar. Engineers at the University of Washington have for the first time used manufacturing techniques at microscopic scales to combine a flexible, biologically safe contact lens with an imprinted electronic circuit and lights.

"Looking through a completed lens, you would see what the display is generating superimposed on the world outside," said Babak Parviz, a UW assistant professor of electrical engineering. "This is a very small step toward that goal, but I think it's extremely promising." The results were presented in January at the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers' international conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems by Harvey Ho, a former graduate student of Parviz's now working at Sandia National Laboratories in Livermore, Calif. Other co-authors are Ehsan Saeedi and Samuel Kim in the UW's electrical engineering department and Tueng Shen in the UW Medical Center's ophthalmology department.

There are many possible uses for virtual displays. Drivers or pilots could see a vehicle's speed projected onto the windshield. Video-game companies could use the contact lenses to completely immerse players in a virtual world without restricting their range of motion. And for communications, people on the go could surf the Internet on a midair virtual display screen that only they would be able to see.

"People may find all sorts of applications for it that we have not thought about. Our goal is to demonstrate the basic technology and make sure it works and that it's safe," said Parviz, who heads a multi-disciplinary UW group that is developing electronics for contact lenses.

The prototype device contains an electric circuit as well as red light-emitting diodes for a display, though it does not yet light up. The lenses were tested on rabbits for up to 20 minutes and the animals showed no adverse effects.

Ideally, installing or removing the bionic eye would be as easy as popping a contact lens in or out, and once installed the wearer would barely know the gadget was there, Parviz said.

Read more:

The device to make this happen may be familiar. Engineers at the University of Washington have for the first time used manufacturing techniques at microscopic scales to combine a flexible, biologically safe contact lens with an imprinted electronic circuit and lights.

The device to make this happen may be familiar. Engineers at the University of Washington have for the first time used manufacturing techniques at microscopic scales to combine a flexible, biologically safe contact lens with an imprinted electronic circuit and lights. "Looking through a completed lens, you would see what the display is generating superimposed on the world outside," said Babak Parviz, a UW assistant professor of electrical engineering. "This is a very small step toward that goal, but I think it's extremely promising." The results were presented in January at the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers' international conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems by Harvey Ho, a former graduate student of Parviz's now working at Sandia National Laboratories in Livermore, Calif. Other co-authors are Ehsan Saeedi and Samuel Kim in the UW's electrical engineering department and Tueng Shen in the UW Medical Center's ophthalmology department.

There are many possible uses for virtual displays. Drivers or pilots could see a vehicle's speed projected onto the windshield. Video-game companies could use the contact lenses to completely immerse players in a virtual world without restricting their range of motion. And for communications, people on the go could surf the Internet on a midair virtual display screen that only they would be able to see.

"People may find all sorts of applications for it that we have not thought about. Our goal is to demonstrate the basic technology and make sure it works and that it's safe," said Parviz, who heads a multi-disciplinary UW group that is developing electronics for contact lenses.

The prototype device contains an electric circuit as well as red light-emitting diodes for a display, though it does not yet light up. The lenses were tested on rabbits for up to 20 minutes and the animals showed no adverse effects.

Ideally, installing or removing the bionic eye would be as easy as popping a contact lens in or out, and once installed the wearer would barely know the gadget was there, Parviz said.

Read more:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)