“Wow. Such f---ing bullsh-t.”

No, this is not a snippet from the latest Quentin Tarantino film. It’s Stanford professor Jay Wacker

responding, on the Q&A site Quora, to the now-infamous TEDx talk “Vortex-Based Mathematics.”

A member had posed the question “Is Randy Powell saying anything in his 2010 TEDxCharlotte talk, or is it just total nonsense?” Wacker, a particle physicist, was unambiguous: “I am a theoretical physicist who uses (and teaches) the technical meaning of many of the jargon terms that he’s throwing out. And he is simply doing a random word association with the terms. Basically, he’s either (1) insane, (2) a huckster going for fame or money, or (3) doing a

Sokal’s hoax on TED. I’d bet equal parts 1 & 2.”

Powell’s talk had been given in September 2010, at what was one of numerous local TEDx gatherings spun off by TED, a nonprofit that puts on highly respected global conferences about ideas. But the talk went relatively unnoticed until the spring of 2012, when a few influential science bloggers discovered it—and excoriated it.

One dared his readers to see how much of the talk they could get through before they had to be “loaded into an ambulance with an aneurysm.”

Another simply described it as “sweet merciful crap.” By August the uproar had gone mainstream, as other questionable TEDx content was uncovered. The New Republic

wrote, “TED is no longer a responsible curator of ideas ‘worth spreading.’ Instead it has become something ludicrous.” As others piled on, TED staffers called Powell and asked him to send the research backing up his claims. He never did.

The TEDxCharlotte talk, which had received tremendous applause when delivered, was one of thousands produced annually by an extended community of people who neither get paid by nor officially work for TED but who are nonetheless capable of damaging its brand.

When it was founded, in 1984, TED (which stands for “Technology, Entertainment, and Design”) brought together a few hundred people in a single annual conference in California. Today, TED is not just an organizer of private conferences; it’s a global phenomenon with $45 million in revenues. In 2006 the nonprofit decided to make all its talks available free on the internet. (They are now also

translated—by volunteers—into more than 90 languages.) Three years later it decided to further democratize the idea-spreading process by letting licensees use its technology and brand platform. This would allow anyone, anywhere, to manage and stage local, independent TEDx events. Licenses are free, but event organizers must apply for them and submit to light vetting. Since 2009 some 5,000 events have been held around the world. (Disclosure: I spoke at the main TED event in February this year.) (...)

Crowds will organize themselves far faster than you could manage, which is great when they’re holding events for you around the world—like TEDxKibera and TEDxAntarcticPeninsula—but not so great when they’re setting up ones that feature “experts” in pseudoscience topics like “plasmatics,” crystal healing, and Egyptian psychoaromatherapy, all of which were presented at TEDxValenciaWomen in December 2012. That conference was described by one disappointed viewer as “a mockery...that hurt, in this order, TED, Valencia, women, science, and common sense.” Within 24 hours commentators on

Reddit had picked up the charge; by the next day more than 5,000 people had weighed in on Reddit, Twitter, or other social channels.

Two months earlier, in October 2012, TED had removed Randy Powell’s “Vortex-Based Mathematics” video and had begun to respond to public concerns about that particular talk on a few influential websites like Quora. But those small steps did not address the fundamental problem: The TED name had become associated with bad content, as the chortle-inducing lineup of TEDxValenciaWomen made clear. People who didn’t even know the specifics of those situations but had grown to dislike what TED represented used the occasion to trash the brand—both for its perceived elitism and, somewhat paradoxically, for dumbing down ideas. An angry mob was forming. The dialogue was mean. And, organizationally, it was life threatening because the very premise of TED was being questioned.

by Nilofer Merchant, HBR |

Read more:

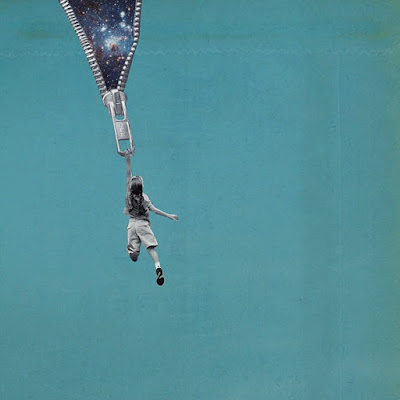

Artwork: Jacob Hashimoto, Forests Collapsed Upon Forests, 2009, acrylic, paper, thread, bamboo, wood, Martha Otero Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Curtis Steinback