Saturday, March 23, 2013

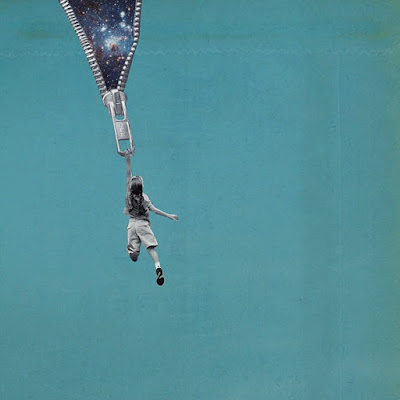

I Grew Up in the Future

What is it supposed to be? I asked, getting the milk out of the fridge and making myself some muesli.

Well, she said, you joined a social network on your phone, and then you could express opinions about things. You could send something to your friends, and they would say if they liked it or they didn’t like it — on their phones.

That sounds really stupid, I said.

But, as I don’t think I need to stress, the idea turned out to have legs. In my defence, the first iPhone was still six months away. And though I was one of the first few million users of Facebook, the ‘Like’ button wouldn’t come along for years.

The future arrived much earlier in our house than anywhere else because my mother is an emerging technologies consultant. Her career has included stints as a circus horse groom, a tropical agronomist in Mauritania, and a desktop publisher. But for most of my life she has lived by her unusual ability to see beyond the glitchy demos of new tech to the faint outlines of another reality, just over the horizon. She takes these trembling hatchlings of ideas by the elbow, murmurs reassurances, and runs as fast as she can into the unknown.

When the web and I were both young, in the mid-1990s (with 10,000 pages and a third-grade education to our respective names), video conferencing was my mom’s thing. We had our county’s first T1 fibre-optic line thanks to her, and I grew up in a house full of webcams, shuddering and starting with pictures of strangers in Hong Kong, New York and the Netherlands, to whom I’d have to wave when I got home from school. Later on, when I bought a webcam for the first time, I could not believe you had to pay for them — I thought of them as a readily available natural resource, spilling out from cardboard boxes under beds.

My mother worked with companies who wanted to develop software and hardware for video conferencing, and she wrote reports about the state of the market, which, at that point, was a slender stream of early adopters. Internet connections were so slight, and the hardware so bulky and expensive, that it was slow going — tech start-ups launched with fanfare and sank within months, unable to stay afloat on the ethereal promise of everyone, everywhere, seeing each other talk. The promise, too, of never having to travel for business was not as appealing as the start-ups thought it would be.

But my mom is a futurist, that peculiar subclass of optimists who believe they can see the day after tomorrow coming. In the 1990s, she ordered pens customised with her consultancy name and the slogan: ‘Remember when we could only hear each other?’ Years later, when an unopened box of them surfaced in her office, she laughed and laughed. It would be another several years before Skype with video brought the rest of the world up to speed with her pens.

And by that point, she’d moved on.

by Veronique Greenwood, Aeon | Read more:

Photo by Everett Collection / Rex Features

Unfit for Work

In the past three decades, the number of Americans who are on disability has skyrocketed. The rise has come even as medical advances have allowed many more people to remain on the job, and new laws have banned workplace discrimination against the disabled. Every month, 14 million people now get a disability check from the government.

The federal government spends more money each year on cash payments for disabled former workers than it spends on food stamps and welfare combined. Yet people relying on disability payments are often overlooked in discussions of the social safety net. People on federal disability do not work. Yet because they are not technically part of the labor force, they are not counted among the unemployed.

The federal government spends more money each year on cash payments for disabled former workers than it spends on food stamps and welfare combined. Yet people relying on disability payments are often overlooked in discussions of the social safety net. People on federal disability do not work. Yet because they are not technically part of the labor force, they are not counted among the unemployed.

In other words, people on disability don't show up in any of the places we usually look to see how the economy is doing. But the story of these programs -- who goes on them, and why, and what happens after that -- is, to a large extent, the story of the U.S. economy. It's the story not only of an aging workforce, but also of a hidden, increasingly expensive safety net.

For the past six months, I've been reporting on the growth of federal disability programs. I've been trying to understand what disability means for American workers, and, more broadly, what it means for poor people in America nearly 20 years after we ended welfare as we knew it. Here's what I found.

In Hale County, Alabama, 1 in 4 working-age adults is on disability. On the day government checks come in every month, banks stay open late, Main Street fills up with cars, and anybody looking to unload an old TV or armchair has a yard sale.

Sonny Ryan, a retired judge in town, didn't hear disability cases in his courtroom. But the subject came up often. He described one exchange he had with a man who was on disability but looked healthy.

"Just out of curiosity, what is your disability?" the judge asked from the bench.

"I have high blood pressure," the man said.

"So do I," the judge said. "What else?"

"I have diabetes."

"So do I."

There's no diagnosis called disability. You don't go to the doctor and the doctor says, "We've run the tests and it looks like you have disability." It's squishy enough that you can end up with one person with high blood pressure who is labeled disabled and another who is not. (...)

People don't seem to be faking this pain, but it gets confusing. I have back pain. My editor has a herniated disc, and he works harder than anyone I know. There must be millions of people with asthma and diabetes who go to work every day. Who gets to decide whether, say, back pain makes someone disabled?

As far as the federal government is concerned, you're disabled if you have a medical condition that makes it impossible to work. In practice, it's a judgment call made in doctors' offices and courtrooms around the country. The health problems where there is most latitude for judgment -- back pain, mental illness -- are among the fastest growing causes of disability.

by Chana Joffe-Walt, NPR | Read more:

The federal government spends more money each year on cash payments for disabled former workers than it spends on food stamps and welfare combined. Yet people relying on disability payments are often overlooked in discussions of the social safety net. People on federal disability do not work. Yet because they are not technically part of the labor force, they are not counted among the unemployed.

The federal government spends more money each year on cash payments for disabled former workers than it spends on food stamps and welfare combined. Yet people relying on disability payments are often overlooked in discussions of the social safety net. People on federal disability do not work. Yet because they are not technically part of the labor force, they are not counted among the unemployed.In other words, people on disability don't show up in any of the places we usually look to see how the economy is doing. But the story of these programs -- who goes on them, and why, and what happens after that -- is, to a large extent, the story of the U.S. economy. It's the story not only of an aging workforce, but also of a hidden, increasingly expensive safety net.

For the past six months, I've been reporting on the growth of federal disability programs. I've been trying to understand what disability means for American workers, and, more broadly, what it means for poor people in America nearly 20 years after we ended welfare as we knew it. Here's what I found.

In Hale County, Alabama, 1 in 4 working-age adults is on disability. On the day government checks come in every month, banks stay open late, Main Street fills up with cars, and anybody looking to unload an old TV or armchair has a yard sale.

Sonny Ryan, a retired judge in town, didn't hear disability cases in his courtroom. But the subject came up often. He described one exchange he had with a man who was on disability but looked healthy.

"Just out of curiosity, what is your disability?" the judge asked from the bench.

"I have high blood pressure," the man said.

"So do I," the judge said. "What else?"

"I have diabetes."

"So do I."

There's no diagnosis called disability. You don't go to the doctor and the doctor says, "We've run the tests and it looks like you have disability." It's squishy enough that you can end up with one person with high blood pressure who is labeled disabled and another who is not. (...)

People don't seem to be faking this pain, but it gets confusing. I have back pain. My editor has a herniated disc, and he works harder than anyone I know. There must be millions of people with asthma and diabetes who go to work every day. Who gets to decide whether, say, back pain makes someone disabled?

As far as the federal government is concerned, you're disabled if you have a medical condition that makes it impossible to work. In practice, it's a judgment call made in doctors' offices and courtrooms around the country. The health problems where there is most latitude for judgment -- back pain, mental illness -- are among the fastest growing causes of disability.

by Chana Joffe-Walt, NPR | Read more:

Image: Brinson Banks for NPR

What Coke Contains

Each can originated in a small town of 4,000 people on the Murray River in Western Australia called Pinjarra. Pinjarra is the site of the world’s largest bauxite mine. Bauxite is surface mined — basically scraped and dug from the top of the ground. The bauxite is crushed and washed with hot sodium hydroxide, which separates it into aluminum hydroxide and waste material called red mud. The aluminum hydroxide is cooled, then heated to over a thousand degrees celsius in a kiln, where it becomes aluminum oxide, or alumina. The alumina is dissolved in a molten substance called cryolite, a rare mineral first discovered in Greenland, and turned into pure aluminum using electricity in a process called electrolysis. The pure aluminum sinks to the bottom of the molten cryolite, is drained off and placed in a mold. It cools into the shape of a long cylindrical bar. The bar is transported west again, to the Port of Bunbury, and loaded onto a container ship bound for — in the case of Coke for sale in Los Angeles — Long Beach.

The bar is transported to Downey, California, where it is rolled flat in a rolling mill, and turned into aluminum sheets. The sheets are punched into circles and shaped into a cup by a mechanical process called drawing and ironing — this not only makes the can but also thins the aluminum. The transition from flat circle to something that resembles a can takes about a fifth of a second. The outside of the can is decorated using a base layer of urethane acrylate, then up to seven layers of colored acrylic paint and varnish that is cured using ultra violet light, and the inside of the can is painted too — with a complex chemical called a comestible polymeric coating that prevents any of the aluminum getting into the soda. So far, this vast tool chain has only produced an empty, open can with no lid. The next step is to fill it.

Coca-Cola is made from a syrup produced by the Coca-Cola Company of Atlanta. The main ingredient in the formula used in the United States is a sweetener called high-fructose corn syrup 55, so named because it is 55 per cent fructose or “fruit sugar” and 42 per cent glucose or “simple sugar” — the same ratio of fructose to glucose as natural honey. HFCS is made by grinding wet corn until it becomes cornstarch. The cornstarch is mixed with an enzyme secreted by a rod-shaped bacterium called Bacillus and an enzyme secreted by a mold called Aspergillus. This process creates the glucose. A third enzyme, also derived from bacteria, is then used to turn some of the glucose into fructose.

The second ingredient, caramel coloring, gives the drink its distinctive dark brown color. There are four types of caramel coloring — Coca Cola uses type E150d, which is made by heating sugars with sulfite and ammonia to create bitter brown liquid. The syrup’s other principal ingredient is phosphoric acid, which adds acidity and is made by diluting burnt phosphorus (created by heating phosphate rock in an arc-furnace) and processing it to remove arsenic.

by Kevin Ashton, Medium | Read more:

Image: uncredited, h/t YMFY

Friday, March 22, 2013

The Circus of Fashion

We were once described as “black crows” — us fashion folk gathered outside an abandoned, crumbling downtown building in a uniform of Comme des Garçons or Yohji Yamamoto. “Whose funeral is it?” passers-by would whisper with a mix of hushed caring and ghoulish inquiry, as we lined up for the hip, underground presentations back in the 1990s.

Today, the people outside fashion shows are more like peacocks than crows. They pose and preen, in their multipatterned dresses, spidery legs balanced on club-sandwich platform shoes, or in thigh-high boots under sculptured coats blooming with flat flowers.

There is likely to be a public stir when a group of young Japanese women spot their idol on parade: the Italian clothes peg Anna Dello Russo. Tall, slim, with a toned and tanned body, the designer and fashion editor is a walking display for designer goods: The wider the belt, the shorter and puffier the skirt, the more outré the shoes, the better. The crowd around her tweets madly: Who is she wearing? Has she changed her outfit since the last show? When will she wear her own H&M collection? Who gave her those mile-high shoes?!

You can hardly get up the steps at Lincoln Center, in New York, or walk along the Tuileries Garden path in Paris because of all the photographers snapping at the poseurs. Cameras point as wildly at their prey as those original paparazzi in Fellini’s “La Dolce Vita.” But now subjects are ready and willing to be objects, not so much hunted down by the paparazzi as gagging for their attention.

by Suzy Menkes, NY Times | Read more:

Marcy Swingle/Gastrochic; Avenue Magazine; Kamel Lahmadi/Style and the CityPhotographers in the Tuileries in Paris.The Glass Arm

On a warm, windy day in Tampa, everyone—fans, coaches, other pitchers—stops what they’re doing to watch Brett Marshall throw. It’s just a warm-up, with no actual game action scheduled for a few more days, so he’s not really letting it fly, but he doesn’t have to. Everyone is still staring.

It’s not the velocity, although that’s there. It’s not the distinctive thump of the ball hitting the catcher’s mitt the way it does only for those blessed with such lightning arms. It’s how easy it looks. Each motion looks like the last motion, which looks like the last motion, which looks like the last motion. The fastball comes in at a consistent 94 mph, but it’s the changeup, widely considered his best pitch, that you have to keep an eye out for; the arm action is perfectly deceptive for being so repeatable. Marshall looks fluid and simple, like he could throw forever. To watch him pitch is to think that throwing a baseball is the most natural thing in the world. When he finishes, a group of fans standing on a walkway above burst into applause. He has simply been playing catch.

In the clubhouse afterward, Marshall is taking a sip of water and checking his iPhone with his non-throwing hand. He is 22 years old and seems unaware of the show he’s just put on. The display is over, just another workout session in a career full of them. Marshall has been in the Yankees organization for five seasons, and has climbed through the team’s minor-league ranks at the exact pace you’d want him to. He will likely spend this season in Triple-A Scranton, one stop from the bigs, where guaranteed contracts and the major-league-minimum salary of $490,000 a year, at the very least, await. If he puts up the kind of numbers scouts think he’s capable of—double-digit wins, with a 4.00 ERA, 175 innings a season, say—he could well earn $10 million a year or more. He’s on the verge of becoming a millionaire and playing for the New York Yankees in front of the entire world. And he knows it could all blow up in a second. “You just want your arm to hold up,” he says. “You have to not think about it. I do not, man. Not at all.”

There’s something strange about almost every snapshot ever taken of a professional baseball pitcher while he’s in his windup or his release: They look grotesque. A pitcher throwing, when you freeze the action mid-movement, does not look dramatically different from a basketball player spraining his ankle or a football player twisting his knee. His arm is almost hideously contorted.

“It is an unnatural motion,” says former Mets pitcher and current MLB Network analyst Al Leiter, who missed roughly three years of his career with arm injuries. “If it were natural, we would all be walking around with our hands above our heads. It’s not normal to throw a ball above your head.”

Ever since Moneyball, baseball has had just about everything figured it out. General managers know that on-base percentage is more important than batting average, that college players are more reliable draft targets than high-school players, that the sacrifice bunt is typically a waste of an out. The game has never been more closely studied or better understood. And yet, even now, no one seems to have a clue about how to keep pitchers from getting hurt.

Pitchers’ health has always been a vital part of the game, but it’s arguably never been more important than it is today. In the post-Bonds-McGwire-Sosa era (if not necessarily the post-PED era), pitching is dominant to a degree it hasn’t been in years. In the past three seasons, MLB teams scored an average of roughly 4.3 runs per game. The last time the average was anywhere near as low was 1992, at 4.12. In 2000, the heyday of Bonds & Co., it was 5.14. A team with great pitching is, in essence, a great team. Pitchers themselves have never stood to gain, or lose, as much as they do now. The last time scoring was this low, the average baseball salary had reached $1 million for the first time and the minimum salary was $109,000. Now that average salary is $3.2 million. Stay healthy, and you’re crazy-rich. Blow out your elbow, and it’s back to hoping your high-school team needs a coach.

And yet, for all the increased importance of pitching, pitchers are getting hurt more often than they used to. In 2011, according to research by FanGraphs.com, pitchers spent a total of 14,926 days on the disabled list. In 1999, that number was 13,129. No one is sure why this is happening, or what to do about it, but what is certain is that teams are trying desperately to divine answers to those questions. Figuring out which pitchers are least likely to get hurt and helping pitchers keep from getting hurt is the game’s next big mystery to solve, the next market inefficiency to be exploited. The modern baseball industry is brilliant at projecting what players will do on the field. The next task is solving the riddle of how to keep them on it.

It’s not the velocity, although that’s there. It’s not the distinctive thump of the ball hitting the catcher’s mitt the way it does only for those blessed with such lightning arms. It’s how easy it looks. Each motion looks like the last motion, which looks like the last motion, which looks like the last motion. The fastball comes in at a consistent 94 mph, but it’s the changeup, widely considered his best pitch, that you have to keep an eye out for; the arm action is perfectly deceptive for being so repeatable. Marshall looks fluid and simple, like he could throw forever. To watch him pitch is to think that throwing a baseball is the most natural thing in the world. When he finishes, a group of fans standing on a walkway above burst into applause. He has simply been playing catch.

In the clubhouse afterward, Marshall is taking a sip of water and checking his iPhone with his non-throwing hand. He is 22 years old and seems unaware of the show he’s just put on. The display is over, just another workout session in a career full of them. Marshall has been in the Yankees organization for five seasons, and has climbed through the team’s minor-league ranks at the exact pace you’d want him to. He will likely spend this season in Triple-A Scranton, one stop from the bigs, where guaranteed contracts and the major-league-minimum salary of $490,000 a year, at the very least, await. If he puts up the kind of numbers scouts think he’s capable of—double-digit wins, with a 4.00 ERA, 175 innings a season, say—he could well earn $10 million a year or more. He’s on the verge of becoming a millionaire and playing for the New York Yankees in front of the entire world. And he knows it could all blow up in a second. “You just want your arm to hold up,” he says. “You have to not think about it. I do not, man. Not at all.”

There’s something strange about almost every snapshot ever taken of a professional baseball pitcher while he’s in his windup or his release: They look grotesque. A pitcher throwing, when you freeze the action mid-movement, does not look dramatically different from a basketball player spraining his ankle or a football player twisting his knee. His arm is almost hideously contorted.

“It is an unnatural motion,” says former Mets pitcher and current MLB Network analyst Al Leiter, who missed roughly three years of his career with arm injuries. “If it were natural, we would all be walking around with our hands above our heads. It’s not normal to throw a ball above your head.”

Ever since Moneyball, baseball has had just about everything figured it out. General managers know that on-base percentage is more important than batting average, that college players are more reliable draft targets than high-school players, that the sacrifice bunt is typically a waste of an out. The game has never been more closely studied or better understood. And yet, even now, no one seems to have a clue about how to keep pitchers from getting hurt.

Pitchers’ health has always been a vital part of the game, but it’s arguably never been more important than it is today. In the post-Bonds-McGwire-Sosa era (if not necessarily the post-PED era), pitching is dominant to a degree it hasn’t been in years. In the past three seasons, MLB teams scored an average of roughly 4.3 runs per game. The last time the average was anywhere near as low was 1992, at 4.12. In 2000, the heyday of Bonds & Co., it was 5.14. A team with great pitching is, in essence, a great team. Pitchers themselves have never stood to gain, or lose, as much as they do now. The last time scoring was this low, the average baseball salary had reached $1 million for the first time and the minimum salary was $109,000. Now that average salary is $3.2 million. Stay healthy, and you’re crazy-rich. Blow out your elbow, and it’s back to hoping your high-school team needs a coach.

And yet, for all the increased importance of pitching, pitchers are getting hurt more often than they used to. In 2011, according to research by FanGraphs.com, pitchers spent a total of 14,926 days on the disabled list. In 1999, that number was 13,129. No one is sure why this is happening, or what to do about it, but what is certain is that teams are trying desperately to divine answers to those questions. Figuring out which pitchers are least likely to get hurt and helping pitchers keep from getting hurt is the game’s next big mystery to solve, the next market inefficiency to be exploited. The modern baseball industry is brilliant at projecting what players will do on the field. The next task is solving the riddle of how to keep them on it.

by Will Leitch, NY Magazine | Read more:

Photo: Pari DukovicThursday, March 21, 2013

Lockheed Martin's Herculean Efforts

When I was a kid obsessed with military aircraft, I loved Chicago's O'Hare airport. If I was lucky and scored a window seat, I might get to see a line of C-130 Hercules transport planes parked on the tarmac in front of the 928th Airlift Wing's hangars. For a precious moment on takeoff or landing, I would have a chance to stare at those giant gray beasts with their snub noses and huge propellers until they passed from sight.

When I was a kid obsessed with military aircraft, I loved Chicago's O'Hare airport. If I was lucky and scored a window seat, I might get to see a line of C-130 Hercules transport planes parked on the tarmac in front of the 928th Airlift Wing's hangars. For a precious moment on takeoff or landing, I would have a chance to stare at those giant gray beasts with their snub noses and huge propellers until they passed from sight.What I didn't know then was why the Air Force Reserve, as well as the Air National Guard, had squadrons of these big planes eternally parked at O'Hare and many other airports and air stations around the country. It’s a tale made to order for this time of sequestration that makes a mockery of all the hyperbole about how any spending cuts will "hollow out" our forces and "devastate" our national security.

Consider this a parable to help us see past the alarmist talking points issued by defense contractor lobbyists, the public relations teams they hire, and the think tanks they fund. It may help us see just how effective defense contractors are in growing their businesses, whatever the mood of the moment.

Meet the Herk

The C-130 Hercules is a mid-sized transport airplane designed to airlift people or cargo around a theater of operations. It dates back to the Korean War, when the Air Force decided that it needed a next generation ("NextGen") transport plane. In 1951, it asked for designs, and Lockheed won the competition. The first C-130s were delivered three years after the war ended.

The C-130 Hercules, or Herk for short, isn't a sexy plane. It hasn't inspired hit Hollywood films, though it has prompted a few photo books, a beer, and a "Robby the C-130" trilogy for children whose military parents are deployed. It has a fat sausage fuselage, that snub nose, overhead wings with two propellers each, and a big back gate that comes down to load and unload up to 21 tons of cargo.

The Herk can land on short runways, even ones made of dirt or grass; it can airdrop parachutists or cargo; it can carry four drones under its wings; it can refuel aircraft; it can fight forest fires; it can morph into a frightening gunship. It's big and strong and can do at least 12 types of labor -- hence, Hercules.

Too Much of a Good Thing

Here's where the story starts to get interesting. After 25 years, the Pentagon decided that it was well stocked with C-130s, so President Jimmy Carter’s administration stopped asking Congress for more of them.

Lockheed was in trouble. A few years earlier, the Air Force had started looking into replacing the Hercules with a new medium-sized transport plane that could handle really short runways, and Lockheed wasn't selected as one of the finalists. Facing bankruptcy due to cost overruns and cancellations of programs, the company squeezed Uncle Sam for a bailout of around $1 billion in loan guarantees and other relief (which was unusual back then, as William Hartung points out his magisterial Prophets of War: Lockheed Martin and the Making of the Military-Industrial Complex).

Then a scandal exploded when it was revealed that Lockheed had proceeded to spend some $22 million of those funds in bribes to foreign officials to persuade them to buy its aircraft. This helped prompt Congress to pass the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

So what did Lockheed do about the fate of the C-130? It bypassed the Pentagon and went straight to Congress. Using a procedure known as a congressional "add-on" -- that is, an earmark -- Lockheed was able to sell the military another fleet of C-130s that it didn’t want.

To be fair, the Air Force did request some C-130s. Thanks to Senator John McCain, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) did a study of how many more C-130s the Air Force requested between 1978 and 1998. The answer: Five.

How many did Congress add on? Two hundred and fifty-six.

As Hartung commented, this must “surely [be] a record in pork-barrel politics.”

by Jeremiah Goulka, TomDispatch | Read more:

Image via: Flightglobal

One of Us

That is technical language, but it speaks to a riddle age-old and instinctive. These thoughts begin, for most of us, typically, in childhood, when we are making eye contact with a pet or wild animal. I go back to our first family dog, a preternaturally intelligent-seeming Labrador mix, the kind of dog who herds playing children away from the street at birthday parties, an animal who could sense if you were down and would nuzzle against you for hours, as if actually sharing your pain. I can still hear people, guests and relatives, talking about how smart she was. “Smarter than some people I know!” But when you looked into her eyes—mahogany discs set back in the grizzled black of her face—what was there? I remember the question forming in my mind: can she think? The way my own brain felt to me, the sensation of existing inside a consciousness, was it like that in there?

For most of the history of our species, we seem to have assumed it was. Trying to recapture the thought life of prehistoric peoples is a game wise heads tend to leave alone, but if there’s a consistent motif in the artwork made between four thousand and forty thousand years ago, it’s animal-human hybrids, drawings and carvings and statuettes showing part man or woman and part something else—lion or bird or bear. Animals knew things, possessed their forms of wisdom. They were beings in a world of countless beings. Taking their lives was a meaningful act, to be prayed for beforehand and atoned for afterward, suggesting that beasts were allowed some kind of right. We used our power over them constantly and violently, but stopped short of telling ourselves that creatures of alien biology could not be sentient or that they were incapable oftrue suffering and pleasure. Needing their bodies, we killed them in spite of those things.

Only with the Greeks does there enter the notion of a formal divide between our species, our animal, and every other on earth. Today in Greece you can walk by a field and hear two farmers talking about an alogo, a horse. An a-logos. No logos, no language. That’s where one of their words for horse comes from. The animal has no speech; it has no reason. It has no reason because it has no speech. Plato and Aristotle were clear on that. Admire animals aesthetically, perhaps, or sentimentally; otherwise they’re here to be used. Mute equaled brute. As time went by, the word for speech became the very word for rationality, the logos, an identification taken up by the early Christians, with fateful results. For them the matter was even simpler. The animals lack souls. They are all animal, whereas we are part divine.

by John Jeremiah Sullivan, Lapham's Quarterly | Read more:

Image: Anguish (1880), by August Friedrich SchenckSee No Evil: The Case of Alfred Anaya

Anaya’s customers typically took advantage of this deal when their fiendishly loud subwoofers blew out or their fiberglass speaker boxes developed hairline cracks. But in late January 2009, a man whom Anaya knew only as Esteban called for help with a more exotic product: a hidden compartment that Anaya had installed in his Ford F-150 pickup truck. Over the years, these secret stash spots—or traps, as they’re known in automotive slang—have become a popular luxury item among the wealthy and shady alike. This particular compartment was located behind the truck’s backseat, which Anaya had rigged with a set of hydraulic cylinders linked to the vehicle’s electrical system. The only way to make the seat slide forward and reveal its secret was by pressing and holding four switches simultaneously: two for the power door locks and two for the windows. (...)

The forefather of modern trap making was a French mechanic who went by the name of Claude Marceau (possibly a pseudonym). According to a 1973 Justice Department report, Marceau personally welded 160 pounds of heroin into the frame of a Lancia limousine that was shipped to the US in 1970—a key triumph for the fabled French Connection, the international smuggling ring immortalized in film.

Traps like Marceau’s may be difficult to detect, but they require significant time and expertise to operate. The only way to load and unload one of these “dumb” compartments is by taking a car apart, piece by piece. That makes economic sense for multinational organizations like the French Connection, which infrequently transport massive amounts of narcotics between continents. But domestic traffickers, who must ferry small shipments between cities on a regular basis, can’t sacrifice an entire car every time they make a delivery. They need to be able to store and retrieve their contraband with ease and then reuse the vehicles again and again.

Early drug traffickers stashed their loads in obvious places: wheel wells, spare tires, the nooks of engine blocks. Starting in the early 1980s, however, they switched to what the Drug Enforcement Administration refers to as “urban traps”: medium-size compartments concealed behind electronically controlled facades. The first such stash spots were usually located in the doors of luxury sedans; trap makers, who are often moonlighting auto body specialists, would slice out the door panels and then attach them to the motors that raised and lowered the windows. They soon moved on to building traps in dashboards, seats, and roofs, with button-operated doors secured by magnetic locks. Over time, the magnets gave way to hydraulic cylinders, which made the doors harder to dislodge during police inspections.

By the early 1990s, however, drug traffickers had discovered that these compartments had two major design flaws. The first was that the buttons and switches that controlled the traps’ doors were aftermarket additions to the cars. This made them too easy to locate—police were being trained to look for any widgets that hadn’t been installed on the assembly line.

Second, opening the traps was no great challenge once a cop identified the appropriate button: The compartment’s door would respond to a single press. Sometimes the police would even open traps by accident; a knee or elbow would brush against a button during a vigorous search, and a brick of cocaine would appear as if by magic.

Trap makers responded to the traffickers’ complaints by tapping into the internal electrical systems of cars. They began to connect their compartments to those systems with relays, electromagnetic switches that enable low-power circuits to control higher-power circuits. (Relays are the reason, for example, that the small act of turning an ignition key can start a whole engine.) Some relays won’t let current flow through until several input circuits have been completed—in other words, until several separate actions have been performed. By wiring these switches into cars, trap makers could build compartments that were operated not by aftermarket buttons but by a car’s own factory-installed controls.

by Brendan I. Koerner, Wired | Read more:

Illustration: Paul Pope

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)