Thursday, December 19, 2013

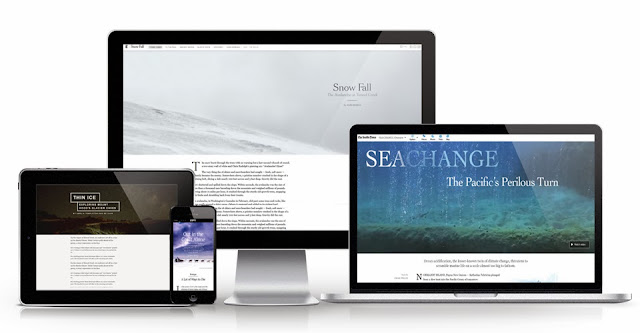

Inspiring Visual Storytelling

Opportunities abound for some creative thinking and here is a round up of some of the best examples of creative online storytelling to inspire you.

So what are the trends in some of the new storytelling projects?

by Heather Bryant, Alaska Media Lab | Read more:

Image: uncredited

R.I.P. The Blog, 1997-2013

Sometime in the past few years, the blog died. In 2014, people will finally notice. Sure, blogs still exist, many of them are excellent, and they will go on existing and being excellent for many years to come. But the function of the blog, the nebulous informational task we all agreed the blog was fulfilling for the past decade, is increasingly being handled by a growing number of disparate media forms that are blog-like but also decidedly not blogs.

Instead of blogging, people are posting to Tumblr, tweeting, pinning things to their board, posting to Reddit, Snapchatting, updating Facebook statuses, Instagramming, and publishing on Medium. In 1997, wired teens created online diaries, and in 2004 the blog was king. Today, teens are about as likely to start a blog (over Instagramming or Snapchatting) as they are to buy a music CD. Blogs are for 40-somethings with kids.I am not generally a bomb-thrower, but I wrote this piece in a deliberately provacative way. Blogs obviously aren’t dead and I acknowledged that much right from the title. I (obviously) think there’s a lot of value in the blog format, even apart from its massive influence on online media in general, but as someone who’s been doing it since 1998 and still does it every day, it’s difficult to ignore the blog’s diminished place in our informational diet. (...)

And yeah, what about Tumblr? Isn’t Tumblr full of blogs? Welllll, sort of. Back in 2005, tumblelogs felt like blogs but there was also something a bit different about them. Today they seem really different…I haven’t thought of Tumblrs as blogs for years…they’re Tumblrs! If you asked a typical 23-year-old Tumblr user what they called this thing they’re doing on the site, I bet “blogging” would not be the first (or second) answer. No one thinks of posting to their Facebook as blogging or tweeting as microblogging or Instagramming as photoblogging. And if the people doing it think it’s different, I’ll take them at their word. After all, when early bloggers were attempting to classify their efforts as something other online diaries or homepages, everyone eventually agreed…let’s not fight everyone else on their choice of subculture and vocabulary.

by Jason Kottke, Kottke.org | Read more:

Facebook Saves Everything

A couple of months ago, a friend of mine asked on Facebook:

A couple of months ago, a friend of mine asked on Facebook:"Do you think that Facebook tracks the stuff that people type and then erase before hitting <enter>? (or the 'post' button)"

Good question.

We spend a lot of time thinking about what to post on Facebook. Should you argue that political point your high school friend made? Do your friends really want to see yet another photo of your cat (or baby)? Most of us have, at one time or another, started writing something and then, probably wisely, changed our minds.

Advertisement

Unfortunately, the code that powers Facebook still knows what you typed – even if you decide not to publish it. It turns out the things you explicitly choose not to share aren't entirely private.

Facebook calls these unposted thoughts "self-censorship", and insights into how it collects these non-posts can be found in a recent paper written by two Facebookers. Sauvik Das, a PhD student at Carnegie Mellon and summer software engineer intern at Facebook, and Adam Kramer, a Facebook data scientist, have put online an article presenting their study of the self-censorship behaviour collected from 5 million English-speaking Facebook users. It reveals a lot about how Facebook monitors our unshared thoughts and what it thinks about them.

The study examined aborted status updates, posts on other people's timelines and comments on others' posts. To collect the text you type, Facebook sends code to your browser. That code automatically analyses what you type into any text box and reports metadata back to Facebook.

Storing text as you type isn't uncommon on other websites. For example, if you use Gmail, your draft messages are automatically saved as you type them. Even if you close the browser without saving, you can usually find a (nearly) complete copy of the email you were typing in your drafts folder. Facebook is using essentially the same technology here. The difference is that Google is saving your messages to help you. Facebook users don't expect their unposted thoughts to be collected, nor do they benefit from it.

It is not clear to the average reader how this data collection is covered by Facebook's privacy policy. In Facebook's Data Use Policy, under a section called "Information we receive and how it is used", it's made clear that the company collects information you choose to share or when you "view or otherwise interact with things". But nothing suggests that it collects content you explicitly don't share. Typing and deleting text in a box could be considered a type of interaction, but I suspect very few of us would expect that data to be saved. When I reached out to Facebook, a representative told me the company believes this self-censorship is a type of interaction covered by the policy.

by Jennifer Golbeck, Sydney Morning Herald | Read more:

Image: Slate

A Life of Noodles Comes Full Circle

At 50, Ivan Orkin appears to have pulled off a chain of unprecedented feats.

He is the first American brave (or foolish) enough to open his own ramen shop in Tokyo. (He now has two.)

He is the first chef to publish a cookbook/memoir, “Ivan Ramen,” in the United States before even opening a restaurant here.

And last week, he may have become the first chef in Manhattan to intercept a bathroom-bound customer and order her back to her seat.

And last week, he may have become the first chef in Manhattan to intercept a bathroom-bound customer and order her back to her seat.

“She got up right after the ramen hit the table!” he said in self-defense, citing the first commandment of ramen: It must be eaten while still volcanically hot.

With the opening of Ivan Ramen Slurp Shop in Hell’s Kitchen last month, Mr. Orkin became a New York restaurateur, a title 20 years in the making. A long stainless-steel counter in his restaurant is lined on one side with customers, and on the other with ramen ingredients: slow-cooked pork belly, scallions, soft-cooked eggs, chicken broth, dashi or seaweed broth, chicken fat, pork fat and his signature rye noodles.

He is having a hard time making peace with those noodles. “I can’t believe I’m not making my own,” he said ruefully. “That was the first thing I got right in Tokyo.” Instead, they are made for him at Sun Noodle in Teterboro, N.J., a supplier to preferred ramen destinations like Momofuku Noodle Bar, Ramen Yebisu and Ganso.

These restaurants are part of a greater New York ramen boom: Traditional purveyors like Ippudo and Totto Ramen are expanding, and mavericks like Mr. Orkin and Yuji Haraguchi of Yuji Ramen are reinventing the bowl. “We are very chef-driven,” said Kenshiro Uki, Sun Noodle’s East Coast manager. The company custom-makes more than 100 variations on ramen: thick and thin, flat and round, wavy and straight, white, yellow and even black, colored with charred bamboo leaf.

It is not hands-on enough for Mr. Orkin, but for now, he doesn’t have the time. His long-chaotic life as a chef has ordered itself around one dish, ramen, and he is racing to build the restaurants that will house his vision. That is not necessarily the most “authentic” ramen, but the ramen of his own Japanese-American-Jewish-chef dreams: a soup with the right balance of pork, chicken, smoked fish, soy and salt; noodles with the ideal combination of chew and give; toppings that set it off instead of overwhelming it. The recipe, as published in “Ivan Ramen,” is 36 pages long.

“I have officially become one of the ramen geeks,” he said.

In Tokyo (and in Japanophile clusters in the United States), ramen is much more than noodles in a rich, meaty broth. Like pizza and burgers in the United States, it has changed from fast food to a canvas of culinary ideas. “Kodawari” ramen is taken seriously and has the same buzzwords as “artisanal” here: free range, long cooked, slow raised, small batch. Ramen is not an ancient dish like sashimi or tofu. While there are vegetarian and seafood versions, the basic soup is rich with fat and meat — which was banned in Japan from approximately the seventh century to the 17th, according to Buddhist edicts.

But it has been popular for long enough to become a national obsession. Ramen otaku — geeks — compete on quiz shows, crowd-source maps and wait hours to try a place with a new twist: whole-grain noodles, for example, or especially thick slices of pork belly. Some ramen shops are famous for their garlicky broths; others for mind-blowing chile heat or intense sesame flavor; others for their strict policies of no talking or no perfume.

He is the first American brave (or foolish) enough to open his own ramen shop in Tokyo. (He now has two.)

He is the first chef to publish a cookbook/memoir, “Ivan Ramen,” in the United States before even opening a restaurant here.

And last week, he may have become the first chef in Manhattan to intercept a bathroom-bound customer and order her back to her seat.

And last week, he may have become the first chef in Manhattan to intercept a bathroom-bound customer and order her back to her seat.“She got up right after the ramen hit the table!” he said in self-defense, citing the first commandment of ramen: It must be eaten while still volcanically hot.

With the opening of Ivan Ramen Slurp Shop in Hell’s Kitchen last month, Mr. Orkin became a New York restaurateur, a title 20 years in the making. A long stainless-steel counter in his restaurant is lined on one side with customers, and on the other with ramen ingredients: slow-cooked pork belly, scallions, soft-cooked eggs, chicken broth, dashi or seaweed broth, chicken fat, pork fat and his signature rye noodles.

He is having a hard time making peace with those noodles. “I can’t believe I’m not making my own,” he said ruefully. “That was the first thing I got right in Tokyo.” Instead, they are made for him at Sun Noodle in Teterboro, N.J., a supplier to preferred ramen destinations like Momofuku Noodle Bar, Ramen Yebisu and Ganso.

These restaurants are part of a greater New York ramen boom: Traditional purveyors like Ippudo and Totto Ramen are expanding, and mavericks like Mr. Orkin and Yuji Haraguchi of Yuji Ramen are reinventing the bowl. “We are very chef-driven,” said Kenshiro Uki, Sun Noodle’s East Coast manager. The company custom-makes more than 100 variations on ramen: thick and thin, flat and round, wavy and straight, white, yellow and even black, colored with charred bamboo leaf.

It is not hands-on enough for Mr. Orkin, but for now, he doesn’t have the time. His long-chaotic life as a chef has ordered itself around one dish, ramen, and he is racing to build the restaurants that will house his vision. That is not necessarily the most “authentic” ramen, but the ramen of his own Japanese-American-Jewish-chef dreams: a soup with the right balance of pork, chicken, smoked fish, soy and salt; noodles with the ideal combination of chew and give; toppings that set it off instead of overwhelming it. The recipe, as published in “Ivan Ramen,” is 36 pages long.

“I have officially become one of the ramen geeks,” he said.

In Tokyo (and in Japanophile clusters in the United States), ramen is much more than noodles in a rich, meaty broth. Like pizza and burgers in the United States, it has changed from fast food to a canvas of culinary ideas. “Kodawari” ramen is taken seriously and has the same buzzwords as “artisanal” here: free range, long cooked, slow raised, small batch. Ramen is not an ancient dish like sashimi or tofu. While there are vegetarian and seafood versions, the basic soup is rich with fat and meat — which was banned in Japan from approximately the seventh century to the 17th, according to Buddhist edicts.

But it has been popular for long enough to become a national obsession. Ramen otaku — geeks — compete on quiz shows, crowd-source maps and wait hours to try a place with a new twist: whole-grain noodles, for example, or especially thick slices of pork belly. Some ramen shops are famous for their garlicky broths; others for mind-blowing chile heat or intense sesame flavor; others for their strict policies of no talking or no perfume.

by Julia Moskin, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Brent HerrigWednesday, December 18, 2013

Rumored Chase-Madoff Settlement Is Another Bad Joke

[ed. See also: The Financial Crisis: Why have no high-level executives been prosecuted?]

Just under two months ago, when the $13 billion settlement for JP Morgan Chase was coming down the chute, word leaked out that that the deal was no sure thing. Among other things, it was said that prosecutors investigating Chase's role in the Bernie Madoff caper – Chase was Madoff's banker – were insisting on a guilty plea to actual criminal charges, but that this was a deal-breaker for Chase.

Something had to give, and now, apparently, it has. Last week, it was reported that the state and Chase were preparing a separate $2 billion deal over the Madoff issues, a series of settlements that would also involve a deferred prosecution agreement.

Something had to give, and now, apparently, it has. Last week, it was reported that the state and Chase were preparing a separate $2 billion deal over the Madoff issues, a series of settlements that would also involve a deferred prosecution agreement.

The deferred-prosecution deal is a hair short of a guilty plea. The bank has to acknowledge the facts of the government's case and pay penalties, but as has become common in the Too-Big-To-Fail arena, we once again have a situation in which all sides will agree that a serious crime has taken place, but no individual has to pay for that crime.

As University of Michigan law professor David Uhlmann noted in a Times editorial at the end of last week, the use of these deferred prosecution agreements has exploded since the infamous Arthur Andersen case. In that affair, the company collapsed and 28,000 jobs were lost after Arthur Andersen was convicted on a criminal charge related to its role in the Enron scandal. As Uhlmann wrote:

Yes, you might very well lose some jobs if you go around indicting huge companies on criminal charges. You might even want to avoid doing so from time to time, if the company is worth saving.

But individuals? There's absolutely no reason why the state can't proceed against the actual people who are guilty of crimes.

Just under two months ago, when the $13 billion settlement for JP Morgan Chase was coming down the chute, word leaked out that that the deal was no sure thing. Among other things, it was said that prosecutors investigating Chase's role in the Bernie Madoff caper – Chase was Madoff's banker – were insisting on a guilty plea to actual criminal charges, but that this was a deal-breaker for Chase.

Something had to give, and now, apparently, it has. Last week, it was reported that the state and Chase were preparing a separate $2 billion deal over the Madoff issues, a series of settlements that would also involve a deferred prosecution agreement.

Something had to give, and now, apparently, it has. Last week, it was reported that the state and Chase were preparing a separate $2 billion deal over the Madoff issues, a series of settlements that would also involve a deferred prosecution agreement.The deferred-prosecution deal is a hair short of a guilty plea. The bank has to acknowledge the facts of the government's case and pay penalties, but as has become common in the Too-Big-To-Fail arena, we once again have a situation in which all sides will agree that a serious crime has taken place, but no individual has to pay for that crime.

As University of Michigan law professor David Uhlmann noted in a Times editorial at the end of last week, the use of these deferred prosecution agreements has exploded since the infamous Arthur Andersen case. In that affair, the company collapsed and 28,000 jobs were lost after Arthur Andersen was convicted on a criminal charge related to its role in the Enron scandal. As Uhlmann wrote:

From 2004 through 2012, the Justice Department entered into 242 deferred prosecution and nonprosecution agreements with corporations; there had been just 26 in the preceding 12 years.Since the AA mess, the state has been beyond hesitant to bring criminal charges against major employers for any reason. (The history of all of this is detailed in The Divide, a book I have coming out early next year.) The operating rationale here is concern for the "collateral consequences" of criminal prosecutions, i.e. the lost jobs that might result from bringing charges against a big company. This was apparently the thinking in the Madoff case as well. As the Times put it in its coverage of the rumored $2 billion settlement:

The government has been reluctant to bring criminal charges against large corporations, fearing that such an action could imperil a company and throw innocent employees out of work. Those fears trace to the indictment of Enron's accounting firm, Arthur Andersen . . .There's only one thing to say about this "reluctance" to prosecute (and the "fear" and "concern" for lost jobs that allegedly drives it): It's a joke.

Yes, you might very well lose some jobs if you go around indicting huge companies on criminal charges. You might even want to avoid doing so from time to time, if the company is worth saving.

But individuals? There's absolutely no reason why the state can't proceed against the actual people who are guilty of crimes.

by Matt Taibbi, Rolling Stone | Read more:

Image: Spencer Platt/Getty Images via:Operation Dead-Mouse Drop

[ed. I hadn't heard about this eradication program until this morning. Apparently, it's still going strong with a fourth drop just recently completed.]

In the U.S. government-funded project, tablets of concentrated acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol, are placed in dead thumb-size mice, which are then used as bait for brown tree snakes.

In the U.S. government-funded project, tablets of concentrated acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol, are placed in dead thumb-size mice, which are then used as bait for brown tree snakes.In humans, acetaminophen helps soothe aches, pains, and fevers. But when ingested by brown tree snakes, the drug disrupts the oxygen-carrying ability of the snakes' hemoglobin blood proteins.

"They go into a coma, and then death," said Peter Savarie, a researcher with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Wildlife Services, which has been developing the technique since 1995 through grants from the U.S. Departments of Defense and Interior.

Only about 80 milligrams of acetaminophen—equal to a child's dose of Tylenol—are needed to kill an adult brown tree snake. Once ingested via a dead mouse, it typically takes about 60 hours for the drug to kill a snake.

"There are very few snakes that will consume something that they haven't killed themselves," added Dan Vice, assistant state director of USDA Wildlife Services in Hawaii, Guam, and the Pacific Islands.

But brown tree snakes will scavenge as well as hunt, he said, and that's the "chink in the brown tree snake's armor." (...)

By contrast, this latest approach aims to take the fight into Guam's jungles, where most of the invasive snakes reside.

A popular misconception about Guam, Vice said, is that the entire island is overrun by brown tree snakes. In reality, most of the snakes are concentrated in the island's jungles, where it is difficult for humans to reach.

"You don't walk out the front door and bump into a snake every morning," Vice said. (...)

Before the laced mice are airdropped, they are attached to "flotation devices" that each consist of two pieces of cardboard joined by a 4-foot-long (1.2-meter-long) paper streamer.

The flotation device was designed to get the bait stuck in upper tree branches, where the brown tree snakes reside, instead of falling to the jungle floor, where the drug-laden mice might inadvertently get eaten by nontarget species, such as monitor lizards.

by Ker Than, National Geographic | Read more:

Image: Vice

Tuesday, December 17, 2013

The Literature of Uprootedness: An Interview with Reinaldo Arenas

[ed. I'm now down to one bookshelf, and most of what I read I discard. Reinaldo Arenas' 'Farewell to the Sea' is one book I will always keep.]

On a fall afternoon in 1983, I interviewed the exiled Cuban author Reinaldo Arenas at Princeton University’s Firestone Library. I was writing my senior thesis on his work and, as part of my study, translating some of his fiction. (My translation of “La Vieja Rosa,” a novella, was later published by Grove.) Though I was nervous about meeting the great man, one of Cuba’s most admired writers, Arenas immediately put me at ease. “Encantado,” he said, smiling and taking my hand. Forty years old at the time, he had thick, curly black hair and enormous, sad eyes; his face was lined and leathery.

On a fall afternoon in 1983, I interviewed the exiled Cuban author Reinaldo Arenas at Princeton University’s Firestone Library. I was writing my senior thesis on his work and, as part of my study, translating some of his fiction. (My translation of “La Vieja Rosa,” a novella, was later published by Grove.) Though I was nervous about meeting the great man, one of Cuba’s most admired writers, Arenas immediately put me at ease. “Encantado,” he said, smiling and taking my hand. Forty years old at the time, he had thick, curly black hair and enormous, sad eyes; his face was lined and leathery.We talked for a while in the library and then went for a drive to a nearby apple orchard. “Ah, a day in the country!” Arenas exclaimed, happy to see the trees and smell the fresh air. We concluded our conversation a couple of hours later on the platform of the train that would take Arenas to Princeton Junction and then back to his derelict apartment in Hell’s Kitchen. In a soft, melodic voice, Arenas answered my questions about his writing process, his influences, and the experience of exile with a natural eloquence and often startling profundity. Below is an edited and condensed version of our conversation, which is being published on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of Arenas’s brilliant memoir, “Before Night Falls.”

Arenas was born in Cuba in 1943, in the eastern province of Oriente. An only child, he spent his time roaming the fields and forests around his family’s farm, captivated by the natural world. In 1959, he joined Castro’s rebels in the mountains, but he soon grew disillusioned. After toiling as an agricultural accountant at a chicken farm, he studied politics and economics in a government-sponsored program at the University of Havana and began working at the National Library, a job that allowed him time to write. (...)

How would you describe your writing process?

I never keep a fixed schedule. I like to write for a while, move around, read, drink something, come back. But when I’ve entered the world of the novel, that demands more concentration. It’s hard to even write a letter, because it means leaving that world. To put aside the typewriter and take out letter paper, or stop because you have to pay the phone bill, is terrible.

I won’t say that I write every day, because I don’t, but I’m always thinking. Often I don’t write anything and instead go to the gym or take a walk. But I’m always with my characters. They start to dominate me and occupy my life, so one way or another I’m working. For me the act of writing, of bringing a certain world to the typewriter, is only one moment of the writing. There are other levels, like investigating the lives of the characters and knowing what it’s like to be with them, seeing what they’re thinking and feeling and then quickly starting to write, so I don’t lose any of it.

There’s a very beautiful moment in the creation of something when you have no idea how far it will go. It’s an almost magical moment, when you’re constructing something from nothing, when this thing comes alive and you feel the characters start to live and you no longer have to live for them.

What would you say about your formal influences or the style that you use?

It depends on the situation. If there’s a moment—as in my novel “Farewell to the Sea”—where you want to satirize all the uniforms, swords, and so forth of a dictator, you can do a caricature of the baroque. If you’re describing the characters’ nightmares, that may be the time for surrealism. All of these techniques or styles can come into play as you realize your vision. For me, an entirely surrealist novel, for example, might end up being of little use because, since anything can happen, nothing has meaning. But there’s a moment for every style. That’s why I advocate an eclectic technique.

One of the most important things in the books I write is rhythm. In poems, short stories, novels. Silence is also very important. I wrote “Farewell to the Sea” in cantos—and silences. And I’ve never been interested in telling a story in a purely anecdotal or linear way. “Realist” literature is, to me, the least realistic, because it eliminates what gives the human his reality, his mystery, his power of creation, of doubt, of dreaming, of thinking, of nightmare. (...)

Is there something that you’d like the reader to understand or see after or while reading your work?

It’s interesting—no one’s ever asked me that. What I want is for people to both think and enjoy while reading. To experience an esthetic enjoyment, pleasure through beauty, rather than through a simple anecdote or social critique. I’m interested in readers perceiving a certain depth, not just something superficial that could be conveyed in a pamphlet. I want them to feel a delight attained through mystery and, of course, I don’t want them to feel they’ve wasted their time.

In general, you have to believe the reader is eternal. If a work of yours that people are reading now endures, it will be read in a hundred years or—optimistically—a thousand. You have to think that way because otherwise you don’t write or you only end up writing newspaper articles.

by Ann Tashi Slater, New Yorker | Read more:

Image: Louis Monier/Gamma-Rapho via Getty

Jose Gonzalez

[ed. Penned by Ryan Adams.]

You Won’t See This on TV

For the past four semesters I’ve taught a criminal justice–themed freshman composition course at a large public university in the Midwest. Each semester I’m amazed at the level of interest my students have for the topic of criminal justice. They’ve spent hundreds of hours watching Law & Order and CSI, read countless mystery novels and “true crime” stories, and sat through big-screen courtroom dramas galore. And yet each semester I’m also amazed by how little they actually know about how the American system of justice works.

In my previous career as a public defender who served thousands of clients, I tried everything from juvenile delinquency allegations to first-degree murder cases. I'm lucky (or, in certain senses, unlucky) to have a perspective on the American criminal justice system that most will never have. I can tell that my students care deeply about justice but do not have the language or the facts they need to discuss the criminal justice system cogently. They are uninformed because popular media, however it is packaged, is ultimately aimed at entertainment—or the provocation of misdirected outrage—rather than instruction.

In my previous career as a public defender who served thousands of clients, I tried everything from juvenile delinquency allegations to first-degree murder cases. I'm lucky (or, in certain senses, unlucky) to have a perspective on the American criminal justice system that most will never have. I can tell that my students care deeply about justice but do not have the language or the facts they need to discuss the criminal justice system cogently. They are uninformed because popular media, however it is packaged, is ultimately aimed at entertainment—or the provocation of misdirected outrage—rather than instruction.

Hollywood is always an unwelcome participant in conversations about criminal justice, in my view. Certain scions of criminal justice–themed entertainment argue that they are educating a generation—Dick Wolf, the creator of Law & Order and its spawn, is one prominent example—but the truth is significantly more interesting than scriptwriters’ fiction.

That is why it’s important to help set the record straight. Hopefully these fifteen truths will act as a starting point for those civilians who want to change our criminal justice system but are not sure where to start.

None of what follows should be construed as legal advice. This is merely a bare-bones description of how important sectors of our criminal justice system work. You could learn much of this simply by sitting in the public gallery at a local courthouse for a few weeks, or by reading any trial practice manual intended for working attorneys.

• • •

1) Prosecutors are trained to charge cases using the maximum allowable number of criminal statutes, with preference always given to the statutes with the highest maximum term of imprisonment. The reason for this is that prosecutors know that more than 90 percent of their cases will end with a plea negotiation, so charging what is reasonable rather than what is possible is strategically unwise. The assumption behind what is termed “over-charging” is that some fresh-faced defense attorney will ensure, through zealous plea negotiations sometime in the future, that the final disposition of each case is a fair one. The problem is that with so few public resources devoted to the defense of the indigent in court, poor defendants are often assigned a well-intentioned but overworked attorney. The predictable result is that defendants too often plead to charges that necessitate terms of imprisonment that even prosecutors—were they unbiased observers—would not consider just.

As to why nearly every criminal statute in America is written so broadly that it can be egregiously misused in this way, the answer is simple: politicians enact criminal statutes, and voters’ limited understanding of the criminal justice system means that at the polls they nearly always reward whoever endorses the broadest and most draconian laws. How else to keep our communities safe from the ever-present scourge of violent crime, even when violent offenses are decreasing in number?

By the time you or a loved one of yours has been caught in the trap of an overbroad criminal statute with an outrageous series of penalties attached—often mandatory ones that even an independent-minded judge cannot contravene—it is too late to get wise to how obtuse, inflexible, and nonsensical most of our criminal statutes are. While the U.S. Sentencing Commission recently announced that it would revisit mandatory minimum sentences, there is little hope of repairing the devastation such sentences have already caused. Nor is there much reason for confidence that any proposed changes will stem the tide of injustice. While Attorney General Eric Holder’s August 12th announcement that mandatory minimum sentences will no longer be sought for low-level, nonviolent drug offenders is a good start, the fact that sentencing guidelines remain a largely political calculation means that the next presidential administration may well undo whatever progress Holder’s Department of Justice makes this year.

2) Most defendants charged with a crime are guilty of doing something contrary to the law, which is a good thing—else we find ourselves living in a fascist police state. However, for the reasons stated above, it’s often the case that a given defendant did not do precisely what he is charged with doing and consequently will be convicted for doing something other than what he did do. The most common juridical misfire of this sort is one in which a defendant is charged with and convicted of a crime more serious than what he’s actually responsible for. Rarely are defendants charged under criminal statutes less serious than the ones that would accurately describe their conduct. This is why actually innocent or minimally culpable individuals sometimes do confess either to crimes they didn't commit or to crimes much more serious than those they are really guilty of. They are afraid, not unreasonably, that at trial they will be wrongfully convicted on one or more over-charged counts and thus sentenced to a much longer county jail or state prison term than they would have faced under a plea agreement.

In my previous career as a public defender who served thousands of clients, I tried everything from juvenile delinquency allegations to first-degree murder cases. I'm lucky (or, in certain senses, unlucky) to have a perspective on the American criminal justice system that most will never have. I can tell that my students care deeply about justice but do not have the language or the facts they need to discuss the criminal justice system cogently. They are uninformed because popular media, however it is packaged, is ultimately aimed at entertainment—or the provocation of misdirected outrage—rather than instruction.

In my previous career as a public defender who served thousands of clients, I tried everything from juvenile delinquency allegations to first-degree murder cases. I'm lucky (or, in certain senses, unlucky) to have a perspective on the American criminal justice system that most will never have. I can tell that my students care deeply about justice but do not have the language or the facts they need to discuss the criminal justice system cogently. They are uninformed because popular media, however it is packaged, is ultimately aimed at entertainment—or the provocation of misdirected outrage—rather than instruction.Hollywood is always an unwelcome participant in conversations about criminal justice, in my view. Certain scions of criminal justice–themed entertainment argue that they are educating a generation—Dick Wolf, the creator of Law & Order and its spawn, is one prominent example—but the truth is significantly more interesting than scriptwriters’ fiction.

That is why it’s important to help set the record straight. Hopefully these fifteen truths will act as a starting point for those civilians who want to change our criminal justice system but are not sure where to start.

None of what follows should be construed as legal advice. This is merely a bare-bones description of how important sectors of our criminal justice system work. You could learn much of this simply by sitting in the public gallery at a local courthouse for a few weeks, or by reading any trial practice manual intended for working attorneys.

• • •

1) Prosecutors are trained to charge cases using the maximum allowable number of criminal statutes, with preference always given to the statutes with the highest maximum term of imprisonment. The reason for this is that prosecutors know that more than 90 percent of their cases will end with a plea negotiation, so charging what is reasonable rather than what is possible is strategically unwise. The assumption behind what is termed “over-charging” is that some fresh-faced defense attorney will ensure, through zealous plea negotiations sometime in the future, that the final disposition of each case is a fair one. The problem is that with so few public resources devoted to the defense of the indigent in court, poor defendants are often assigned a well-intentioned but overworked attorney. The predictable result is that defendants too often plead to charges that necessitate terms of imprisonment that even prosecutors—were they unbiased observers—would not consider just.

As to why nearly every criminal statute in America is written so broadly that it can be egregiously misused in this way, the answer is simple: politicians enact criminal statutes, and voters’ limited understanding of the criminal justice system means that at the polls they nearly always reward whoever endorses the broadest and most draconian laws. How else to keep our communities safe from the ever-present scourge of violent crime, even when violent offenses are decreasing in number?

By the time you or a loved one of yours has been caught in the trap of an overbroad criminal statute with an outrageous series of penalties attached—often mandatory ones that even an independent-minded judge cannot contravene—it is too late to get wise to how obtuse, inflexible, and nonsensical most of our criminal statutes are. While the U.S. Sentencing Commission recently announced that it would revisit mandatory minimum sentences, there is little hope of repairing the devastation such sentences have already caused. Nor is there much reason for confidence that any proposed changes will stem the tide of injustice. While Attorney General Eric Holder’s August 12th announcement that mandatory minimum sentences will no longer be sought for low-level, nonviolent drug offenders is a good start, the fact that sentencing guidelines remain a largely political calculation means that the next presidential administration may well undo whatever progress Holder’s Department of Justice makes this year.

2) Most defendants charged with a crime are guilty of doing something contrary to the law, which is a good thing—else we find ourselves living in a fascist police state. However, for the reasons stated above, it’s often the case that a given defendant did not do precisely what he is charged with doing and consequently will be convicted for doing something other than what he did do. The most common juridical misfire of this sort is one in which a defendant is charged with and convicted of a crime more serious than what he’s actually responsible for. Rarely are defendants charged under criminal statutes less serious than the ones that would accurately describe their conduct. This is why actually innocent or minimally culpable individuals sometimes do confess either to crimes they didn't commit or to crimes much more serious than those they are really guilty of. They are afraid, not unreasonably, that at trial they will be wrongfully convicted on one or more over-charged counts and thus sentenced to a much longer county jail or state prison term than they would have faced under a plea agreement.

by Seth Abramson, Boston Review | Read more:

Image: Aapo HaapanenThree Tweets for the Web

[ed. See also: 2013 The Year 'the Stream' Crested.]

The arrival of virtually every new cultural medium has been greeted with the charge that it truncates attention spans and represents the beginning of cultural collapse—the novel (in the 18th century), the comic book, rock ‘n’ roll, television, and now the Web. In fact, there has never been a golden age of all-wise, all-attentive readers. But that’s not to say that nothing has changed. The mass migration of intellectual activity from print to the Web has brought one important development: We have begun paying more attention to information. Overall, that’s a big plus for the new world order.

The arrival of virtually every new cultural medium has been greeted with the charge that it truncates attention spans and represents the beginning of cultural collapse—the novel (in the 18th century), the comic book, rock ‘n’ roll, television, and now the Web. In fact, there has never been a golden age of all-wise, all-attentive readers. But that’s not to say that nothing has changed. The mass migration of intellectual activity from print to the Web has brought one important development: We have begun paying more attention to information. Overall, that’s a big plus for the new world order.

It is easy to dismiss this cornucopia as information overload. We’ve all seen people scrolling with one hand through a BlackBerry while pecking out instant messages (IMs) on a laptop with the other and eyeing a television (I won’t say “watching”). But even though it is easy to see signs of overload in our busy lives, the reality is that most of us carefully regulate this massive inflow of information to create something uniquely suited to our particular interests and needs—a rich and highly personalized blend of cultural gleanings.

The word for this process is multitasking, but that makes it sound as if we’re all over the place. There is a deep coherence to how each of us pulls out a steady stream of information from disparate sources to feed our long-term interests. No matter how varied your topics of interest may appear to an outside observer, you’ll tailor an information stream related to the continuing “stories” you want in your life—say, Sichuan cooking, health care reform, Michael Jackson, and the stock market. With the help of the Web, you build broader intellectual narratives about the world. The apparent disorder of the information stream reflects not your incoherence but rather your depth and originality as an individual. (...)

With the help of technology, we are honing our ability to do many more things at once and do them faster. We access and absorb information more quickly than before, and, as a result, we often seem more impatient. If you use Google to look something up in 10 seconds rather than spend five minutes searching through an encyclopedia, that doesn’t mean you are less patient. It means you are creating more time to focus on other matters. In fact, we’re devoting more effort than ever before to big-picture questions, from the nature of God to the best age for marrying and the future of the U.S. economy.

Our focus on cultural bits doesn’t mean we are neglecting the larger picture. Rather, those bits are building-blocks for seeing and understanding larger trends and narratives. The typical Web user doesn’t visit a gardening blog one day and a Manolo Blahnik shoes blog the next day, and never return to either. Most activity online, or at least the kind that persists, involves continuing investments in particular long-running narratives—about gardening, art, shoes, or whatever else engages us. There’s an alluring suspense to it.What’s next? That is why the Internet captures so much of our attention.

Indeed, far from shortening our attention spans, the Web lengthens them by allowing us to follow the same story over many years’ time. If I want to know what’s new with the NBA free-agent market, the debate surrounding global warming, or the publication plans of Thomas Pynchon, Google quickly gets me to the most current information. Formerly I needed personal contacts—people who were directly involved in the action—to follow a story for years, but now I can do it quite easily.

Sometimes it does appear I am impatient. I’ll discard a half-read book that 20 years ago I might have finished. But once I put down the book, I will likely turn my attention to one of the long-running stories I follow online. I’ve been listening to the music of Paul McCartney for more than 30 years, for example, and if there is some new piece of music or development in his career, I see it first on the Internet. If our Web surfing is sometimes frantic or pulled in many directions, that is because we care so much about so many long-running stories. It could be said, a bit paradoxically, that we are impatient to return to our chosen programs of patience.

Another way the Web has affected the human attention span is by allowing greater specialization of knowledge. It has never been easier to wrap yourself up in a long-term intellectual project without at the same time losing touch with the world around you. Some critics don’t see this possibility, charging that the Web is destroying a shared cultural experience by enabling us to follow only the specialized stories that pique our individual interests. But there are also those who argue that the Web is doing just the opposite—that we dabble in an endless variety of topics but never commit to a deeper pursuit of a specific interest. These two criticisms contradict each other. The reality is that the Internet both aids in knowledge specialization and helps specialists keep in touch with general trends.

The key to developing your personal blend of all the “stuff” that’s out there is to use the right tools. The quantity of information coming our way has exploded, but so has the quality of our filters, including Google, blogs, and Twitter. As Internet analyst Clay Shirky points out, there is no information overload, only filter failure. If you wish, you can keep all the information almost entirely at bay and use Google or text a friend only when you need to know something. That’s not usually how it works. Many of us are cramming ourselves with Web experiences—videos, online chats, magazines—and also fielding a steady stream of incoming e-mails, text messages, and IMs. The resulting sense of time pressure is not a pathology; it is a reflection of the appeal and intensity of what we are doing.

The arrival of virtually every new cultural medium has been greeted with the charge that it truncates attention spans and represents the beginning of cultural collapse—the novel (in the 18th century), the comic book, rock ‘n’ roll, television, and now the Web. In fact, there has never been a golden age of all-wise, all-attentive readers. But that’s not to say that nothing has changed. The mass migration of intellectual activity from print to the Web has brought one important development: We have begun paying more attention to information. Overall, that’s a big plus for the new world order.

The arrival of virtually every new cultural medium has been greeted with the charge that it truncates attention spans and represents the beginning of cultural collapse—the novel (in the 18th century), the comic book, rock ‘n’ roll, television, and now the Web. In fact, there has never been a golden age of all-wise, all-attentive readers. But that’s not to say that nothing has changed. The mass migration of intellectual activity from print to the Web has brought one important development: We have begun paying more attention to information. Overall, that’s a big plus for the new world order.It is easy to dismiss this cornucopia as information overload. We’ve all seen people scrolling with one hand through a BlackBerry while pecking out instant messages (IMs) on a laptop with the other and eyeing a television (I won’t say “watching”). But even though it is easy to see signs of overload in our busy lives, the reality is that most of us carefully regulate this massive inflow of information to create something uniquely suited to our particular interests and needs—a rich and highly personalized blend of cultural gleanings.

The word for this process is multitasking, but that makes it sound as if we’re all over the place. There is a deep coherence to how each of us pulls out a steady stream of information from disparate sources to feed our long-term interests. No matter how varied your topics of interest may appear to an outside observer, you’ll tailor an information stream related to the continuing “stories” you want in your life—say, Sichuan cooking, health care reform, Michael Jackson, and the stock market. With the help of the Web, you build broader intellectual narratives about the world. The apparent disorder of the information stream reflects not your incoherence but rather your depth and originality as an individual. (...)

With the help of technology, we are honing our ability to do many more things at once and do them faster. We access and absorb information more quickly than before, and, as a result, we often seem more impatient. If you use Google to look something up in 10 seconds rather than spend five minutes searching through an encyclopedia, that doesn’t mean you are less patient. It means you are creating more time to focus on other matters. In fact, we’re devoting more effort than ever before to big-picture questions, from the nature of God to the best age for marrying and the future of the U.S. economy.

Our focus on cultural bits doesn’t mean we are neglecting the larger picture. Rather, those bits are building-blocks for seeing and understanding larger trends and narratives. The typical Web user doesn’t visit a gardening blog one day and a Manolo Blahnik shoes blog the next day, and never return to either. Most activity online, or at least the kind that persists, involves continuing investments in particular long-running narratives—about gardening, art, shoes, or whatever else engages us. There’s an alluring suspense to it.What’s next? That is why the Internet captures so much of our attention.

Indeed, far from shortening our attention spans, the Web lengthens them by allowing us to follow the same story over many years’ time. If I want to know what’s new with the NBA free-agent market, the debate surrounding global warming, or the publication plans of Thomas Pynchon, Google quickly gets me to the most current information. Formerly I needed personal contacts—people who were directly involved in the action—to follow a story for years, but now I can do it quite easily.

Sometimes it does appear I am impatient. I’ll discard a half-read book that 20 years ago I might have finished. But once I put down the book, I will likely turn my attention to one of the long-running stories I follow online. I’ve been listening to the music of Paul McCartney for more than 30 years, for example, and if there is some new piece of music or development in his career, I see it first on the Internet. If our Web surfing is sometimes frantic or pulled in many directions, that is because we care so much about so many long-running stories. It could be said, a bit paradoxically, that we are impatient to return to our chosen programs of patience.

Another way the Web has affected the human attention span is by allowing greater specialization of knowledge. It has never been easier to wrap yourself up in a long-term intellectual project without at the same time losing touch with the world around you. Some critics don’t see this possibility, charging that the Web is destroying a shared cultural experience by enabling us to follow only the specialized stories that pique our individual interests. But there are also those who argue that the Web is doing just the opposite—that we dabble in an endless variety of topics but never commit to a deeper pursuit of a specific interest. These two criticisms contradict each other. The reality is that the Internet both aids in knowledge specialization and helps specialists keep in touch with general trends.

The key to developing your personal blend of all the “stuff” that’s out there is to use the right tools. The quantity of information coming our way has exploded, but so has the quality of our filters, including Google, blogs, and Twitter. As Internet analyst Clay Shirky points out, there is no information overload, only filter failure. If you wish, you can keep all the information almost entirely at bay and use Google or text a friend only when you need to know something. That’s not usually how it works. Many of us are cramming ourselves with Web experiences—videos, online chats, magazines—and also fielding a steady stream of incoming e-mails, text messages, and IMs. The resulting sense of time pressure is not a pathology; it is a reflection of the appeal and intensity of what we are doing.

by Tyler Cowen, Wilson Quarterly | Read more:

Image: TechBuffalo

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)