In about 40 minutes, Cindy Manit will let a complete stranger into her car. An app on her windshield-mounted iPhone will summon her to a corner in San Francisco’s South of Market neighborhood, where a russet-haired woman in an orange raincoat and coffee-colored boots will slip into the front seat of her immaculate 2006 Mazda3 hatchback and ask for a ride to the airport. Manit has picked up hundreds of random people like this. Once she took a fare all the way across the Golden Gate Bridge to Sausalito. Another time she drove a clown to a Cirque du Soleil after-party.

“People might think I’m a little too trusting,” Manit says as she drives toward Potrero Hill, “but I don’t think so.”

“People might think I’m a little too trusting,” Manit says as she drives toward Potrero Hill, “but I don’t think so.”

Manit, a freelance yoga instructor and personal trainer, signed up in August 2012 as a driver for Lyft, the then-nascent ride-sharing company that lets anyone turn their car into an ad hoc taxi. Today the company has thousands of drivers, has raised $333 million in venture funding, and is considered one of the leading participants in the so-called sharing economy, in which businesses provide marketplaces for individuals to rent out their stuff or labor. Over the past few years, the sharing economy has matured from a fringe movement into a legitimate economic force, with companies like Airbnb and Uber the constant subject of IPO rumors. (One of these startups may well have filed an S-1 by the time you read this.) No less an authority than New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman has declared this the age of the sharing economy, which is “producing both new entrepreneurs and a new concept of ownership.”

The sharing economy has come on so quickly and powerfully that regulators and economists are still grappling to understand its impact. But one consequence is already clear: Many of these companies have us engaging in behaviors that would have seemed unthinkably foolhardy as recently as five years ago. We are hopping into strangers’ cars (Lyft, Sidecar, Uber), welcoming them into our spare rooms (Airbnb), dropping our dogs off at their houses (DogVacay, Rover), and eating food in their dining rooms (Feastly). We are letting them rent our cars (RelayRides, Getaround), our boats (Boatbound), our houses (HomeAway), and our power tools (Zilok). We are entrusting complete strangers with our most valuable possessions, our personal experiences—and our very lives. In the process, we are entering a new era of Internet-enabled intimacy.

This is not just an economic breakthrough. It is a cultural one, enabled by a sophisticated series of mechanisms, algorithms, and finely calibrated systems of rewards and punishments. It’s a radical next step for the person-to-person marketplace pioneered by eBay: a set of digital tools that enable and encourage us to trust our fellow human beings.

Manit is 30 years old but has the delicate frame of an adolescent. She wears a thin kelly-green hoodie and distressed blue jeans, and her cropped dark hair pokes out from under her purple stocking cap. Yet despite her seemingly vulnerable appearance, she says she has never felt threatened or uneasy while driving for Lyft. “It’s not just some person off the street,” she says, tooling under the 101 off-ramp and ticking off the ways in which driving for Lyft is different from picking up a random hitchhiker. Lyft riders must link their account to their Facebook profile; their photo pops up on Manit’s iPhone when they request a ride. Every rider has been rated by their previous Lyft drivers, so Manit can spot bad apples and avoid them. And they have to register with a credit card, so the ride is guaranteed to be paid for before they even get into her car. “I’ve never done anything like this, where I pick up random people,” Manit says, “but I’ve gotten used to it.”

Then again, Manit has what academics call a low trust threshold. That is, she is predisposed to engage in behavior that other people might consider risky. “I don’t want to live my life always guarding myself. I put it out there,” she says. “But when I told my friends and family about it—even my partner at the time—they were like, uh, are you sure? This seems kind of creepy.”

“People might think I’m a little too trusting,” Manit says as she drives toward Potrero Hill, “but I don’t think so.”

“People might think I’m a little too trusting,” Manit says as she drives toward Potrero Hill, “but I don’t think so.”Manit, a freelance yoga instructor and personal trainer, signed up in August 2012 as a driver for Lyft, the then-nascent ride-sharing company that lets anyone turn their car into an ad hoc taxi. Today the company has thousands of drivers, has raised $333 million in venture funding, and is considered one of the leading participants in the so-called sharing economy, in which businesses provide marketplaces for individuals to rent out their stuff or labor. Over the past few years, the sharing economy has matured from a fringe movement into a legitimate economic force, with companies like Airbnb and Uber the constant subject of IPO rumors. (One of these startups may well have filed an S-1 by the time you read this.) No less an authority than New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman has declared this the age of the sharing economy, which is “producing both new entrepreneurs and a new concept of ownership.”

The sharing economy has come on so quickly and powerfully that regulators and economists are still grappling to understand its impact. But one consequence is already clear: Many of these companies have us engaging in behaviors that would have seemed unthinkably foolhardy as recently as five years ago. We are hopping into strangers’ cars (Lyft, Sidecar, Uber), welcoming them into our spare rooms (Airbnb), dropping our dogs off at their houses (DogVacay, Rover), and eating food in their dining rooms (Feastly). We are letting them rent our cars (RelayRides, Getaround), our boats (Boatbound), our houses (HomeAway), and our power tools (Zilok). We are entrusting complete strangers with our most valuable possessions, our personal experiences—and our very lives. In the process, we are entering a new era of Internet-enabled intimacy.

This is not just an economic breakthrough. It is a cultural one, enabled by a sophisticated series of mechanisms, algorithms, and finely calibrated systems of rewards and punishments. It’s a radical next step for the person-to-person marketplace pioneered by eBay: a set of digital tools that enable and encourage us to trust our fellow human beings.

Manit is 30 years old but has the delicate frame of an adolescent. She wears a thin kelly-green hoodie and distressed blue jeans, and her cropped dark hair pokes out from under her purple stocking cap. Yet despite her seemingly vulnerable appearance, she says she has never felt threatened or uneasy while driving for Lyft. “It’s not just some person off the street,” she says, tooling under the 101 off-ramp and ticking off the ways in which driving for Lyft is different from picking up a random hitchhiker. Lyft riders must link their account to their Facebook profile; their photo pops up on Manit’s iPhone when they request a ride. Every rider has been rated by their previous Lyft drivers, so Manit can spot bad apples and avoid them. And they have to register with a credit card, so the ride is guaranteed to be paid for before they even get into her car. “I’ve never done anything like this, where I pick up random people,” Manit says, “but I’ve gotten used to it.”

Then again, Manit has what academics call a low trust threshold. That is, she is predisposed to engage in behavior that other people might consider risky. “I don’t want to live my life always guarding myself. I put it out there,” she says. “But when I told my friends and family about it—even my partner at the time—they were like, uh, are you sure? This seems kind of creepy.”

by Jason Tanz, Wired | Read more:

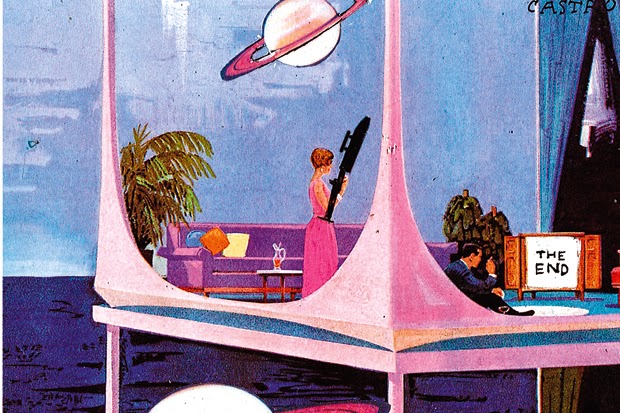

Image: Gus Powell