Over the past few years, when media outlets reached out to Theranos about whether its wunderkind founder, Elizabeth Holmes, would have time to sit for an interview, her P.R. team generally responded with two questions: What time and where? Holmes was a star. She bounced between TV networks like a politician giving a stump speech. She sat across from tech bloggers, reporters, and TV cameras who slurped up her delectable story—that she had come up with Theranos, her blood-testing company, as a Stanford freshman who was fearful of needles—and they largely regurgitated it, sometimes beat for beat. Yet in April of 2015, when John Carreyrou, an investigative reporter with

The Wall Street Journal, reached out for an interview with Holmes, he said he got a very different response.

After two months of being stonewalled by the Theranos P.R. team, Carreyrou told me an entourage of lawyers arrived at the

Journal’s Midtown Manhattan offices at one P.M. on June 23. The pack confidently sauntered past editors and reporters in the fifth-floor newsroom and was led by David Boies, the superstar lawyer who has taken on Bill Gates, the U.S. government, and represented Al Gore in the 2000 Florida recount case. Four other attorneys and a Theranos representative accompanied him. Before anything was said, the lawyers placed two audio recorders at either end of the long oval wood table, and recalcitrantly sat across from Carreyrou, his editor, and a

Journal lawyer. Then they hit record.

Almost immediately, one person present told me, Boies and his team threatened legal action against the paper, accusing it of being in possession of “proprietary information” and “trade secrets.” The Theranos legal team then did their best to discredit dozens of independent sources whom Carreyrou had interviewed. The legal team roared, they showed teeth, they tried to intimidate. After a very tense five hours, the person told me that Boies and his platoon exited the newsroom, leaving behind the very serious specter of a lawsuit. (A spokesperson for both Boies and Theranos declined to comment. But one person close to the company said that Boies had been dispatched because Theranos executives had learned that the Journal possessed sensitive internal documents.)

For four months after that meeting, Carreyrou continued to try to secure an interview with Holmes, and for four months he was continuously threatened. Finally, in October, the

Journal published its

now-famous article suggesting that the Theranos narrative was all wrong—that the company’s technology was faulty, that it relied on other companies’ machinery to run many of its tests, and that some of those tests yielded inaccurate results. In fact, as Carreyrou reported, the company was hawking a tale that was too good to be true.

In the months since, the plot has only thickened for Theranos. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

found serious deficiencies in the company’s Newark, California, lab. Theranos is

under federal investigation by the S.E.C. and U.S. Attorney’s Office. Regulators have proposed banning Holmes from her company for two years.

There are a lot of directions in which to point fingers. There is Holmes, of course, who seemed to have repeatedly misrepresented her company. There are also the people who funded her, those who praised her, and the largely older, all-white, and entirely male board of directors, few of whom have any real experience in the medical field, that supposedly oversaw her.

But if you peel back all of the layers of this tale, at the center you will find one of the more insidious culprits: the Silicon Valley tech press. They embraced Holmes and her start-up with a surprising paucity of questions about the technology she had supposedly developed. They praised her as “the next Steve Jobs,” over and over (the black turtleneck didn’t hurt), until it was no longer a question, but seemingly a fact. At TechCrunch Disrupt, blogger Jon Shieberhad his

blood drawn onstage as he interviewed her. There were no tough questions about whether Theranos’s technology actually worked; just praise. When it seemed that the tech press had vetted Holmes, she subsequently went mainstream. She got her

New Yorkerprofile, and her face appeared on the cover of

T: The New York Times Style Magazine, among others. (Holmes appeared on

Vanity Fair’s New Establishment list and spoke at its 2015 New Establishment Summit.)

But it was a passage in that

New Yorker profile, written by Ken Auletta, that led Carreyrou to start questioning the validity of the company. In the piece, Auletta acerbically noted that the technology behind Theranos was “treated as a state secret, and Holmes’s description of the process was comically vague.” She told him, for instance, that one process occurred when “a chemistry is performed so that a chemical reaction occurs and generates a signal from the chemical interaction with the sample, which is translated into a result, which is then reviewed by certified laboratory personnel.”

Carreyrou, a two-time Pulitzer winner, read that passage and (as you probably just did) essentially scratched his head. Soon after, he got a tip from a source who noted, he told me, that “the coverage that the company was getting belied some serious issues” with what was really going on inside Theranos.

So why did Holmes and Theranos get such a break? Was she an anomaly who somehow pulled one over on the tech press in Silicon Valley? Not even close.

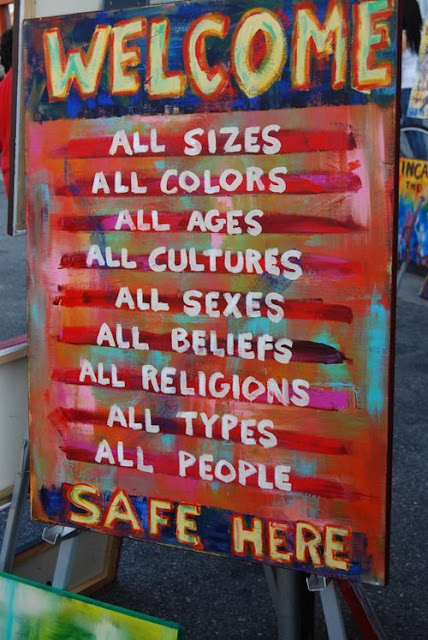

Image: Carlos Chavarria/The New York Times/Redux