Saturday, October 15, 2016

Dads' Rights: Attorneys for Divorcing Dads

Andrew Jones was shocked when his wife started a child custody battle in 2014. The couple had separated five months earlier after, he says, he caught her in a series of extramarital affairs. They had agreed on an informal settlement: he moved from their 2,700 sq ft home into a mobile home, paid her $500 a month in child support and could spend equal time with their five- and three-year-old kids. When he received the letter with a court date, Jones was not hopeful.

“I felt like I wasn’t going to have a life,” says the 46-year-old who works as an HVAC technician. “I heard so many horror stories of divorce and how pretty much women get all your paycheques and you have no way to live.”

“I felt like I wasn’t going to have a life,” says the 46-year-old who works as an HVAC technician. “I heard so many horror stories of divorce and how pretty much women get all your paycheques and you have no way to live.”

Jones (his last name was changed to protect the identity of his children) represented himself in court while his wife hired an attorney who he says is “well-known” in their North Carolina county for “getting women anything and everything they want in court”. The attorney, he says “kind of gives you the feeling that she hates men. That all men are dogs and men don’t want to be in their child’s lives.”

Jones nervously told the judge all he wanted was equal time with his kids. The following month, he received a letter from the court saying he owed $1,300 a month in child support – a payment that would be big stretch on his wage of $26 an hour. He had already cleared out his savings to pay off his and his wife’s combined debts, so to keep up with payments Jones sold his truck, $4,000 worth of tools, and stopped eating out or having a social life. But the money wasn’t even the worst part: he was only allowed to see his kids eight days out of the month.

“When you have kids it changes your life,” he says. “You can’t go without them and [when you do] it wears you down emotionally and physically.”

In family law, tales of fathers who pay exorbitant child support and rarely get to see their kids are commonplace. Recently, firms that specialize in men’s divorce have popped up all over America to capitalize on so-called gender-based discrimination in courts. While many family law firms have seen a drop in divorce filings, these niche attorneys claim business is thriving.

Yet their very existence is controversial. Critics claim any good lawyer is equipped to handle a man’s divorce and that instead of pushing for greater equality under the law, these firms perpetuate sexist stereotypes about women.

While family laws are gender neutral, there’s no doubt that judges and lawyers interpret them based on certain beliefs. In many cases, judges still consider a woman the more natural caretaker, a stubborn holdover from the decades in which mothers only worked at home. (...)

Joseph Cordell, founder of the largest men’s divorce-focused firm in America, says the stereotypes of mothers as nurturers and men as providers leads to systemic discrimination against fathers.

“As a society we’ve made progress regarding gender in a number of areas,” he says. “But the dark corner of the room when it comes to civil rights, I can tell you, is dads’ rights in family courts.”

by Angelina Chapin, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Echo/Getty Images/Cultura RF

“I felt like I wasn’t going to have a life,” says the 46-year-old who works as an HVAC technician. “I heard so many horror stories of divorce and how pretty much women get all your paycheques and you have no way to live.”

“I felt like I wasn’t going to have a life,” says the 46-year-old who works as an HVAC technician. “I heard so many horror stories of divorce and how pretty much women get all your paycheques and you have no way to live.”Jones (his last name was changed to protect the identity of his children) represented himself in court while his wife hired an attorney who he says is “well-known” in their North Carolina county for “getting women anything and everything they want in court”. The attorney, he says “kind of gives you the feeling that she hates men. That all men are dogs and men don’t want to be in their child’s lives.”

Jones nervously told the judge all he wanted was equal time with his kids. The following month, he received a letter from the court saying he owed $1,300 a month in child support – a payment that would be big stretch on his wage of $26 an hour. He had already cleared out his savings to pay off his and his wife’s combined debts, so to keep up with payments Jones sold his truck, $4,000 worth of tools, and stopped eating out or having a social life. But the money wasn’t even the worst part: he was only allowed to see his kids eight days out of the month.

“When you have kids it changes your life,” he says. “You can’t go without them and [when you do] it wears you down emotionally and physically.”

In family law, tales of fathers who pay exorbitant child support and rarely get to see their kids are commonplace. Recently, firms that specialize in men’s divorce have popped up all over America to capitalize on so-called gender-based discrimination in courts. While many family law firms have seen a drop in divorce filings, these niche attorneys claim business is thriving.

Yet their very existence is controversial. Critics claim any good lawyer is equipped to handle a man’s divorce and that instead of pushing for greater equality under the law, these firms perpetuate sexist stereotypes about women.

While family laws are gender neutral, there’s no doubt that judges and lawyers interpret them based on certain beliefs. In many cases, judges still consider a woman the more natural caretaker, a stubborn holdover from the decades in which mothers only worked at home. (...)

Joseph Cordell, founder of the largest men’s divorce-focused firm in America, says the stereotypes of mothers as nurturers and men as providers leads to systemic discrimination against fathers.

“As a society we’ve made progress regarding gender in a number of areas,” he says. “But the dark corner of the room when it comes to civil rights, I can tell you, is dads’ rights in family courts.”

by Angelina Chapin, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Echo/Getty Images/Cultura RF

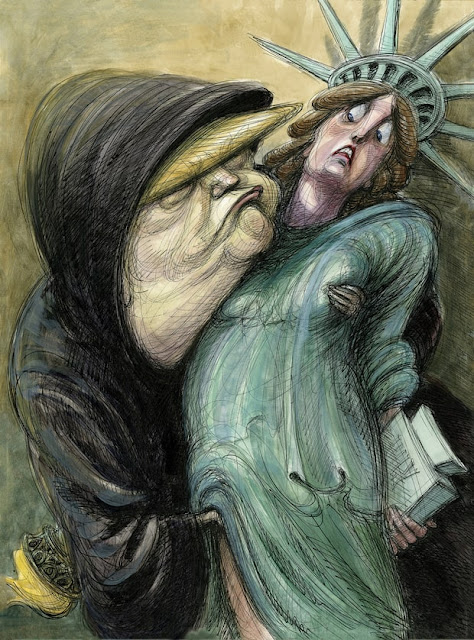

Victor Juhasz

[ed. I'm so ready for this election to be over (like, six months ago) and hesitant to devote one more inch of blog space to Trump, but this is such a great illustration that I couldn't resist reprinting it. It accompanies an article (link below) by the always great Matt Taibbi at Rolling Stone.]

The Fury and Failure of Donald Trump

Friday, October 14, 2016

Forest Bathing Will Improve Your Health

The tonic of the wilderness was Henry David Thoreau’s classic prescription for civilization and its discontents, offered in the 1854 essay Walden: Or, Life in the Woods. Now there’s scientific evidence supporting eco-therapy. The Japanese practice of forest bathing is proven to lower heart rate and blood pressure, reduce stress hormone production, boost the immune system, and improve overall feelings of wellbeing.

Forest bathing—basically just being in the presence of trees—became part of a national public health program in Japan in 1982 when the forestry ministry coined the phrase shinrin-yoku and promoted topiary as therapy. Nature appreciation—picnicking en masse under the cherry blossoms, for example—is a national pastime in Japan, so forest bathing quickly took. The environment’s wisdom has long been evident to the culture: Japan’s Zen masters asked: If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears, does it make a sound?

Forest bathing—basically just being in the presence of trees—became part of a national public health program in Japan in 1982 when the forestry ministry coined the phrase shinrin-yoku and promoted topiary as therapy. Nature appreciation—picnicking en masse under the cherry blossoms, for example—is a national pastime in Japan, so forest bathing quickly took. The environment’s wisdom has long been evident to the culture: Japan’s Zen masters asked: If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears, does it make a sound?

To discover the answer, masters do nothing, and gain illumination. Forest bathing works similarly: Just be with trees. No hiking, no counting steps on a Fitbit. You can sit or meander, but the point is to relax rather than accomplish anything.

“Don’t effort,” says Gregg Berman, a registered nurse, wilderness expert, and certified forest bathing guide in California. He’s leading a small group on the Big Trees Trail in Oakland one cool October afternoon, barefoot among the redwoods. Berman tells the group—wearing shoes—that the human nervous system is both of nature and attuned to it. Planes roar overhead as the forest bathers wander slowly, quietly, under the green cathedral of trees.

From 2004 to 2012, Japanese officials spent about $4 million dollars studying the physiological and psychological effects of forest bathing, designating 48 therapy trails based on the results. Qing Li, a professor at Nippon Medical School in Tokyo, measured the activity of human natural killer (NK) cells in the immune system before after exposure to the woods. These cells provide rapid responses to viral-infected cells and respond to tumor formation, and are associated with immune system health and cancer prevention. In a 2009 study Li’s subjects showed significant increases in NK cell activity in the week after a forest visit, and positive effects lasted a month following each weekend in the woods.

This is due to various essential oils, generally called phytoncide, found in wood, plants, and some fruit and vegetables, which trees emit to protect themselves from germs and insects. Forest air doesn’t just feel fresher and better—inhaling phytoncide seems to actually improve immune system function.

by Ephrat Livni, Quartz | Read more:

Image: via:

Forest bathing—basically just being in the presence of trees—became part of a national public health program in Japan in 1982 when the forestry ministry coined the phrase shinrin-yoku and promoted topiary as therapy. Nature appreciation—picnicking en masse under the cherry blossoms, for example—is a national pastime in Japan, so forest bathing quickly took. The environment’s wisdom has long been evident to the culture: Japan’s Zen masters asked: If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears, does it make a sound?

Forest bathing—basically just being in the presence of trees—became part of a national public health program in Japan in 1982 when the forestry ministry coined the phrase shinrin-yoku and promoted topiary as therapy. Nature appreciation—picnicking en masse under the cherry blossoms, for example—is a national pastime in Japan, so forest bathing quickly took. The environment’s wisdom has long been evident to the culture: Japan’s Zen masters asked: If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears, does it make a sound?To discover the answer, masters do nothing, and gain illumination. Forest bathing works similarly: Just be with trees. No hiking, no counting steps on a Fitbit. You can sit or meander, but the point is to relax rather than accomplish anything.

“Don’t effort,” says Gregg Berman, a registered nurse, wilderness expert, and certified forest bathing guide in California. He’s leading a small group on the Big Trees Trail in Oakland one cool October afternoon, barefoot among the redwoods. Berman tells the group—wearing shoes—that the human nervous system is both of nature and attuned to it. Planes roar overhead as the forest bathers wander slowly, quietly, under the green cathedral of trees.

From 2004 to 2012, Japanese officials spent about $4 million dollars studying the physiological and psychological effects of forest bathing, designating 48 therapy trails based on the results. Qing Li, a professor at Nippon Medical School in Tokyo, measured the activity of human natural killer (NK) cells in the immune system before after exposure to the woods. These cells provide rapid responses to viral-infected cells and respond to tumor formation, and are associated with immune system health and cancer prevention. In a 2009 study Li’s subjects showed significant increases in NK cell activity in the week after a forest visit, and positive effects lasted a month following each weekend in the woods.

This is due to various essential oils, generally called phytoncide, found in wood, plants, and some fruit and vegetables, which trees emit to protect themselves from germs and insects. Forest air doesn’t just feel fresher and better—inhaling phytoncide seems to actually improve immune system function.

by Ephrat Livni, Quartz | Read more:

Image: via:

Fast Fashion is Creating an Environmental Disaster

No one wants your cheap, old clothes—not even the neediest people on Earth.

Visitors who stepped into fashion retailer H&M’s showroom in New York City on April 4, 2016, were confronted by a pile of cast-off clothing reaching to the ceiling. A T.S. Eliot quote stenciled on the wall (“In my end is my beginning”) gave the showroom the air of an art gallery or museum. In the next room, reporters and fashion bloggers sipped wine while studying the half-dozen mannequins wearing bespoke creations pieced together from old jeans, patches of jackets and cut-up blouses.

This cocktail party was to celebrate the launch of H&M’s most recent Conscious Collection. The actress Olivia Wilde, spokeswoman and model for H&M’s forays into sustainable fashion, was there wearing a new dress from the line. But the fast-fashion giant, which has almost 4,000 stores worldwide and earned over $25 billion in sales in 2015, wanted participants to also take notice of its latest initiative: getting customers to recycle their clothes. Or, rather, convincing them to bring in their old clothes (from any brand) and put them in bins in H&M’s stores worldwide. “H&M will recycle them and create new textile fibre, and in return you get vouchers to use at H&M. Everybody wins!” H&M said on its blog.

This cocktail party was to celebrate the launch of H&M’s most recent Conscious Collection. The actress Olivia Wilde, spokeswoman and model for H&M’s forays into sustainable fashion, was there wearing a new dress from the line. But the fast-fashion giant, which has almost 4,000 stores worldwide and earned over $25 billion in sales in 2015, wanted participants to also take notice of its latest initiative: getting customers to recycle their clothes. Or, rather, convincing them to bring in their old clothes (from any brand) and put them in bins in H&M’s stores worldwide. “H&M will recycle them and create new textile fibre, and in return you get vouchers to use at H&M. Everybody wins!” H&M said on its blog.

It’s a nice sentiment, but it’s a gross oversimplification. Only 0.1 percent of all clothing collected by charities and take-back programs is recycled into new textile fiber, according to H&M’s development sustainability manager, Henrik Lampa, who was at the cocktail party answering questions from the press. And despite the impressive amount of marketing dollars the company pumped into World Recycle Week to promote the idea of recycling clothes—including the funding of a music video by M.I.A.—what H&M is doing is nothing special. Its salvaged clothing goes through almost the exact same process as garments donated to, say, Goodwill, or really anywhere else.

Picture yourself with a trash bag of old clothes you’ve just cleaned out of your closet. You think you could get some money out of them, so you take them to a consignment or thrift store, or sell them via one of the new online equivalents, like ThredUp. But they’ll probably reject most of your old clothes, even the ones you paid dearly for, because of small flaws or no longer being in season. With fast fashion speeding up trends and shortening seasons, your clothing is quite likely dated if it’s more than a year old. Many secondhand stores will reject items from fast-fashion chains like Forever 21, H&M, Zara and Topshop. The inexpensive clothing is poor quality, with low resale value, and there’s just too much of it.

If you’re an American, your next step is likely to throw those old clothes in the trash. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 84 percent of unwanted clothes in the United States in 2012 went into either a landfill or an incinerator.

When natural fibers, like cotton, linen and silk, or semi-synthetic fibers created from plant-based cellulose, like rayon, Tencel and modal, are buried in a landfill, in one sense they act like food waste, producing the potent greenhouse gas methane as they degrade. But unlike banana peels, you can’t compost old clothes, even if they're made of natural materials. “Natural fibers go through a lot of unnatural processes on their way to becoming clothing,” says Jason Kibbey, CEO of the Sustainable Apparel Coalition. “They’ve been bleached, dyed, printed on, scoured in chemical baths.” Those chemicals can leach from the textiles and—in improperly sealed landfills—into groundwater. Burning the items in incinerators can release those toxins into the air.

Meanwhile, synthetic fibers, like polyester, nylon and acrylic, have the same environmental drawbacks, and because they are essentially a type of plastic made from petroleum, they will take hundreds of years, if not a thousand, to biodegrade.

Despite these ugly statistics, Americans are blithely trashing more clothes than ever. In less than 20 years, the volume of clothing Americans toss each year has doubled from 7 million to 14 million tons, or an astounding 80 pounds per person. The EPA estimates that diverting all of those often-toxic trashed textiles into a recycling program would be the environmental equivalent of taking 7.3 million cars and their carbon dioxide emissions off the road.

Trashing the clothes is also a huge waste of money. Nationwide, a municipality pays $45 per ton of waste sent to a landfill. It costs New York City $20.6 million annually to ship textiles to landfills and incinerators—a major reason it has become especially interested in diverting unwanted clothing out of the waste stream. The Department of Sanitation’s Re-FashioNYC program, for example, provides large collection bins to buildings with 10 or more units. Housing Works (a New York–based nonprofit that operates used-clothing stores to fund AIDS and homelessness programs) receives the goods, paying Re-FashioNYC for each ton collected, which in turn puts the money toward more bins. Since it launched in 2011, the program has diverted 6.4 million pounds of textiles from landfills, and Housing Works has opened up several new secondhand clothing sales locations.

But that’s only 0.3 percent of the 200,000 tons of textiles going to the dump every year from the city. Just 690 out of the estimated 35,000 or so qualified buildings in the city participate.

Smaller municipalities have tried curbside collection programs, but most go underpublicized and unused. The best bet in most places is to take your old clothing to a charity. Haul your bag to the back door of Goodwill, the Salvation Army or a smaller local shop, get a tax receipt and congratulate yourself on your largess. The clothes are out of your life and off your mind. But their long, international journey may be just beginning.

Made to Not Last

According to the Council for Textile Recycling, charities overall sell only 20 percent of the clothing donated to them at their retail outlets. All the big charities I contacted asserted that they sell more than that—30 percent at Goodwill, 45 to 75 percent at the Salvation Army and 40 percent at Housing Works, to give a few examples. This disparity is probably because, unlike small charity shops, these larger organizations have well-developed systems for processing clothing. If items don’t sell in the main retail store, they can send them to their outlets, where customers can walk out with a bag full of clothing for just a few dollars. But even at that laughably cheap price, they can’t sell everything.

“When it doesn’t sell in the store, or online, or outlets, we have to do something with it,” says Michael Meyer, vice president of donated goods retail and marketing for Goodwill Industries International. So Goodwill—and others—“bale up” the remaining unwanted clothing into shrink-wrapped cubes taller than a person and sell them to textile recyclers.

This outrages people who believe the role of thrift shop charities is to transfer clothes to the needy. “What Really Happens to Your Clothing Donations?” read a Fashionista headline earlier this year. The story hinted, "Let’s just say they’re not all going towards a good cause.”

“People like to feel like they are doing something good, and the problem they run into in a country such as the U.S. is that we don’t have people who need [clothes] on the scale at which we are producing,“ says Pietra Rivoli, a professor of economics at Georgetown University. The nonprofit N Street Village in Washington, D.C., which provides services to homeless and low-income women, says in its wish list that “due to overwhelming support,” it can’t accept any clothing, with the exception of a few particularly useful and hard-to-come-by items like bras and rain ponchos.

Fast fashion is forcing charities to process larger amounts of garments in less time to get the same amount of revenue—like an even more down-market fast-fashion retailer. “We need to go through more and more donations to find those great pieces, which can make it more costly to find those pieces and get them to customers,” says David Raper, senior vice president of business enterprises at Housing Works. Goodwill’s strategy is much the same, says Meyer: “If I can get more fresh product more quickly on the floor, I can extract more value.”

This strategy—advertising new product on a weekly basis—is remarkably similar to that of Spanish fast-fashion retailer Zara, which upended the entire fashion game by restocking new designs twice a week instead of once or twice a season. And so clothing moves through the system faster and faster, seeking somebody, anybody, who will pay a few cents for it.

Visitors who stepped into fashion retailer H&M’s showroom in New York City on April 4, 2016, were confronted by a pile of cast-off clothing reaching to the ceiling. A T.S. Eliot quote stenciled on the wall (“In my end is my beginning”) gave the showroom the air of an art gallery or museum. In the next room, reporters and fashion bloggers sipped wine while studying the half-dozen mannequins wearing bespoke creations pieced together from old jeans, patches of jackets and cut-up blouses.

This cocktail party was to celebrate the launch of H&M’s most recent Conscious Collection. The actress Olivia Wilde, spokeswoman and model for H&M’s forays into sustainable fashion, was there wearing a new dress from the line. But the fast-fashion giant, which has almost 4,000 stores worldwide and earned over $25 billion in sales in 2015, wanted participants to also take notice of its latest initiative: getting customers to recycle their clothes. Or, rather, convincing them to bring in their old clothes (from any brand) and put them in bins in H&M’s stores worldwide. “H&M will recycle them and create new textile fibre, and in return you get vouchers to use at H&M. Everybody wins!” H&M said on its blog.

This cocktail party was to celebrate the launch of H&M’s most recent Conscious Collection. The actress Olivia Wilde, spokeswoman and model for H&M’s forays into sustainable fashion, was there wearing a new dress from the line. But the fast-fashion giant, which has almost 4,000 stores worldwide and earned over $25 billion in sales in 2015, wanted participants to also take notice of its latest initiative: getting customers to recycle their clothes. Or, rather, convincing them to bring in their old clothes (from any brand) and put them in bins in H&M’s stores worldwide. “H&M will recycle them and create new textile fibre, and in return you get vouchers to use at H&M. Everybody wins!” H&M said on its blog.It’s a nice sentiment, but it’s a gross oversimplification. Only 0.1 percent of all clothing collected by charities and take-back programs is recycled into new textile fiber, according to H&M’s development sustainability manager, Henrik Lampa, who was at the cocktail party answering questions from the press. And despite the impressive amount of marketing dollars the company pumped into World Recycle Week to promote the idea of recycling clothes—including the funding of a music video by M.I.A.—what H&M is doing is nothing special. Its salvaged clothing goes through almost the exact same process as garments donated to, say, Goodwill, or really anywhere else.

Picture yourself with a trash bag of old clothes you’ve just cleaned out of your closet. You think you could get some money out of them, so you take them to a consignment or thrift store, or sell them via one of the new online equivalents, like ThredUp. But they’ll probably reject most of your old clothes, even the ones you paid dearly for, because of small flaws or no longer being in season. With fast fashion speeding up trends and shortening seasons, your clothing is quite likely dated if it’s more than a year old. Many secondhand stores will reject items from fast-fashion chains like Forever 21, H&M, Zara and Topshop. The inexpensive clothing is poor quality, with low resale value, and there’s just too much of it.

If you’re an American, your next step is likely to throw those old clothes in the trash. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 84 percent of unwanted clothes in the United States in 2012 went into either a landfill or an incinerator.

When natural fibers, like cotton, linen and silk, or semi-synthetic fibers created from plant-based cellulose, like rayon, Tencel and modal, are buried in a landfill, in one sense they act like food waste, producing the potent greenhouse gas methane as they degrade. But unlike banana peels, you can’t compost old clothes, even if they're made of natural materials. “Natural fibers go through a lot of unnatural processes on their way to becoming clothing,” says Jason Kibbey, CEO of the Sustainable Apparel Coalition. “They’ve been bleached, dyed, printed on, scoured in chemical baths.” Those chemicals can leach from the textiles and—in improperly sealed landfills—into groundwater. Burning the items in incinerators can release those toxins into the air.

Meanwhile, synthetic fibers, like polyester, nylon and acrylic, have the same environmental drawbacks, and because they are essentially a type of plastic made from petroleum, they will take hundreds of years, if not a thousand, to biodegrade.

Despite these ugly statistics, Americans are blithely trashing more clothes than ever. In less than 20 years, the volume of clothing Americans toss each year has doubled from 7 million to 14 million tons, or an astounding 80 pounds per person. The EPA estimates that diverting all of those often-toxic trashed textiles into a recycling program would be the environmental equivalent of taking 7.3 million cars and their carbon dioxide emissions off the road.

Trashing the clothes is also a huge waste of money. Nationwide, a municipality pays $45 per ton of waste sent to a landfill. It costs New York City $20.6 million annually to ship textiles to landfills and incinerators—a major reason it has become especially interested in diverting unwanted clothing out of the waste stream. The Department of Sanitation’s Re-FashioNYC program, for example, provides large collection bins to buildings with 10 or more units. Housing Works (a New York–based nonprofit that operates used-clothing stores to fund AIDS and homelessness programs) receives the goods, paying Re-FashioNYC for each ton collected, which in turn puts the money toward more bins. Since it launched in 2011, the program has diverted 6.4 million pounds of textiles from landfills, and Housing Works has opened up several new secondhand clothing sales locations.

But that’s only 0.3 percent of the 200,000 tons of textiles going to the dump every year from the city. Just 690 out of the estimated 35,000 or so qualified buildings in the city participate.

Smaller municipalities have tried curbside collection programs, but most go underpublicized and unused. The best bet in most places is to take your old clothing to a charity. Haul your bag to the back door of Goodwill, the Salvation Army or a smaller local shop, get a tax receipt and congratulate yourself on your largess. The clothes are out of your life and off your mind. But their long, international journey may be just beginning.

Made to Not Last

According to the Council for Textile Recycling, charities overall sell only 20 percent of the clothing donated to them at their retail outlets. All the big charities I contacted asserted that they sell more than that—30 percent at Goodwill, 45 to 75 percent at the Salvation Army and 40 percent at Housing Works, to give a few examples. This disparity is probably because, unlike small charity shops, these larger organizations have well-developed systems for processing clothing. If items don’t sell in the main retail store, they can send them to their outlets, where customers can walk out with a bag full of clothing for just a few dollars. But even at that laughably cheap price, they can’t sell everything.

“When it doesn’t sell in the store, or online, or outlets, we have to do something with it,” says Michael Meyer, vice president of donated goods retail and marketing for Goodwill Industries International. So Goodwill—and others—“bale up” the remaining unwanted clothing into shrink-wrapped cubes taller than a person and sell them to textile recyclers.

This outrages people who believe the role of thrift shop charities is to transfer clothes to the needy. “What Really Happens to Your Clothing Donations?” read a Fashionista headline earlier this year. The story hinted, "Let’s just say they’re not all going towards a good cause.”

“People like to feel like they are doing something good, and the problem they run into in a country such as the U.S. is that we don’t have people who need [clothes] on the scale at which we are producing,“ says Pietra Rivoli, a professor of economics at Georgetown University. The nonprofit N Street Village in Washington, D.C., which provides services to homeless and low-income women, says in its wish list that “due to overwhelming support,” it can’t accept any clothing, with the exception of a few particularly useful and hard-to-come-by items like bras and rain ponchos.

Fast fashion is forcing charities to process larger amounts of garments in less time to get the same amount of revenue—like an even more down-market fast-fashion retailer. “We need to go through more and more donations to find those great pieces, which can make it more costly to find those pieces and get them to customers,” says David Raper, senior vice president of business enterprises at Housing Works. Goodwill’s strategy is much the same, says Meyer: “If I can get more fresh product more quickly on the floor, I can extract more value.”

This strategy—advertising new product on a weekly basis—is remarkably similar to that of Spanish fast-fashion retailer Zara, which upended the entire fashion game by restocking new designs twice a week instead of once or twice a season. And so clothing moves through the system faster and faster, seeking somebody, anybody, who will pay a few cents for it.

by Jared T. Miller, Newsweek | Read more:

Image: uncredited

Novel Drugs for Depression

It started out as LY110141. Its inventor, Eli Lilly, was not sure what to do with it. Eventually the company found that it seemed to make depressed people happier. So, with much publicity and clever branding, Prozac was born. Prozac would transform the treatment of depression and become the most widely prescribed antidepressant in history. Some users described it as “bottled sunshine”. It attained peak annual sales (in 1998) of $3 billion and at the last count had been used by 54m people in 90 countries. And, along the way, it embedded into the public consciousness a particular idea about how depression works—that it is caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain, which the drug corrects. Unfortunately, this idea seems to be only part of the story.

In science it is good to have a hypothesis to frame one’s thinking. The term “chemical imbalance” is just such a thing. It is a layman’s simplification of the monoamine hypothesis, which has been the prevalent explanation for depression for almost 50 years. Monoamines are a class of chemical that often act as messenger molecules (known technically as neurotransmitters) between nerve cells in the brain. Many antidepressive drugs boost the level of one or other of these chemicals. In the case of Prozac, the monoamine in question is serotonin.

In science it is good to have a hypothesis to frame one’s thinking. The term “chemical imbalance” is just such a thing. It is a layman’s simplification of the monoamine hypothesis, which has been the prevalent explanation for depression for almost 50 years. Monoamines are a class of chemical that often act as messenger molecules (known technically as neurotransmitters) between nerve cells in the brain. Many antidepressive drugs boost the level of one or other of these chemicals. In the case of Prozac, the monoamine in question is serotonin.

The monoamine hypothesis, though, is under attack. One long-standing objection is that, although drugs such as Prozac raise levels of their target monoamine quite quickly, the symptoms of depression may take weeks, or even months to abate—if, indeed, they do abate, for many patients do not respond to such drugs at all. Now, to add to that, a second objection has emerged. This is the discovery that ketamine, a drug long used as an anaesthetic and which is also popular recreationally, works, too, as a fast-acting antidepressant. Ketamine’s mode of action is not primarily on monoamines, so the race is on to use what knowledge there is of the way it does work to design a new class of antidepressant. This is a change of direction so radical that some think it heralds a revolution in psychiatry.

Special K

Ketamine works for 75% of patients who have been resistant to other forms of treatment, such as Prozac (which works in 58% of patients). Moreover, it works in hours, sometimes even minutes, and its effects last for several weeks. A single dose can reduce thoughts of suicide. As a result, although it has not formally been approved for use in depression, it is widely prescribed “off label”, and clinics have sprouted up all over America, in particular, to offer infusions of the drug (which must be taken intravenously, if it is to work). Anecdotal reports suggest that it has already saved many lives.

Ketamine’s rise has been gradual. The discovery of its efficacy against depression happened a decade ago. Conducting clinical trials of new uses for drugs whose patents have expired is not a high priority for pharmaceutical companies, which generally prefer to test new molecules whose patents they own—and without such trials, formal approval for a new use cannot be forthcoming. Now, though, novel ketamine-related treatments are emerging.

In science it is good to have a hypothesis to frame one’s thinking. The term “chemical imbalance” is just such a thing. It is a layman’s simplification of the monoamine hypothesis, which has been the prevalent explanation for depression for almost 50 years. Monoamines are a class of chemical that often act as messenger molecules (known technically as neurotransmitters) between nerve cells in the brain. Many antidepressive drugs boost the level of one or other of these chemicals. In the case of Prozac, the monoamine in question is serotonin.

In science it is good to have a hypothesis to frame one’s thinking. The term “chemical imbalance” is just such a thing. It is a layman’s simplification of the monoamine hypothesis, which has been the prevalent explanation for depression for almost 50 years. Monoamines are a class of chemical that often act as messenger molecules (known technically as neurotransmitters) between nerve cells in the brain. Many antidepressive drugs boost the level of one or other of these chemicals. In the case of Prozac, the monoamine in question is serotonin.The monoamine hypothesis, though, is under attack. One long-standing objection is that, although drugs such as Prozac raise levels of their target monoamine quite quickly, the symptoms of depression may take weeks, or even months to abate—if, indeed, they do abate, for many patients do not respond to such drugs at all. Now, to add to that, a second objection has emerged. This is the discovery that ketamine, a drug long used as an anaesthetic and which is also popular recreationally, works, too, as a fast-acting antidepressant. Ketamine’s mode of action is not primarily on monoamines, so the race is on to use what knowledge there is of the way it does work to design a new class of antidepressant. This is a change of direction so radical that some think it heralds a revolution in psychiatry.

Special K

Ketamine works for 75% of patients who have been resistant to other forms of treatment, such as Prozac (which works in 58% of patients). Moreover, it works in hours, sometimes even minutes, and its effects last for several weeks. A single dose can reduce thoughts of suicide. As a result, although it has not formally been approved for use in depression, it is widely prescribed “off label”, and clinics have sprouted up all over America, in particular, to offer infusions of the drug (which must be taken intravenously, if it is to work). Anecdotal reports suggest that it has already saved many lives.

Ketamine’s rise has been gradual. The discovery of its efficacy against depression happened a decade ago. Conducting clinical trials of new uses for drugs whose patents have expired is not a high priority for pharmaceutical companies, which generally prefer to test new molecules whose patents they own—and without such trials, formal approval for a new use cannot be forthcoming. Now, though, novel ketamine-related treatments are emerging.

by The Economist | Read more:

Image: Dave Simonds

Thursday, October 13, 2016

Dawn of the Planet of the Receivers

Every NFL position has changed dramatically over the past decade: Quarterbacks are more involved than ever; offensive linemen face a harder college-to-pro leap; middle linebackers may be phasing out of the game completely.

But no position has evolved more than wide receiver, which, thanks to a long list of converging forces, has become perhaps the most talent-stacked group in sports. That’s been palpable in this young NFL season, with dominant pass catchers buoying many top teams: Julio Jones delivered a 300-yard performance two weeks ago for the now 4–1 Falcons; Antonio Brown already has 447 yards and five touchdowns for the 4–1 Steelers; A.J. Green has been a rare bright spot for the flailing Bengals; and the list goes on.

Saying that we’re in a golden generation of wide receivers would be a gross understatement. We’re firmly in an era when, from the youth football level on up, nearly every trend in the past decade has favored receivers. And there’s no evidence that the talent gap between wideouts and other positions will close anytime soon. (...)

Saying that we’re in a golden generation of wide receivers would be a gross understatement. We’re firmly in an era when, from the youth football level on up, nearly every trend in the past decade has favored receivers. And there’s no evidence that the talent gap between wideouts and other positions will close anytime soon. (...)

“There’s no doubt the game started changing in the early 2000s,” said Todd Watson, Julio Jones’s former coach at Alabama’s Foley High School and the current director of football operations at Troy University. “The game shifted from ground-and-pound to spread.” Every kid, Watson said, went from wanting to play running back in youth football to wanting to be involved in the passing game.

Watson, who arrived at Foley in 2005 after Jones’s freshman season, witnessed this firsthand: Jones was playing safety and running back when he started his high school career. Watson said that if Jones had played in an earlier era, he may have been instructed to bulk up and play defensive end. High school and youth football teams used to be based on the running game and defense, and a 6-foot-3, 220-pound athlete like Jones could excel at so many important positions that he rarely made it to the world of receiving, but that position gained importance due to schematic changes in the game. The proliferation of the spread offense, which began in the 1990s and exploded in the next decade, created a world where, for the first time, most high school teams needed a dominant receiver — and opted to put their best athletes there.

The explosion of that offense coincided with a change in routine, Watson said: “Kids in a small towns in America were working all summer. But during Julio’s time, it became the norm to train year-round.”

Shortly after the spread took off, spring and summer leagues boomed at the high school level, with seven players facing off on each side of the ball. Watson said players were looking for more ways to compete in the off months, and these 7-on-7 camps filled a big need. Powerhouse high schools like Hoover High School in Alabama hosted tournaments. Players traveled their regions to find leagues, some of which are run by high schools, some by independent companies. All have one thing in common: Their reliance on passing helps receivers improve.

The 7-on-7 concept is fairly straightforward: a 40-yard field, no tackling, no pads, and very little live-football action. There’s no pressure on quarterbacks. Defenses can’t tackle, lay a hit to break up a pass, or shed blockers. Receiver is, by far, the position with the 7-on-7 skill set that most closely resembles what those players will eventually need to succeed in a game. In a confined space, receivers aren’t able to rely as fully on their natural speed, forcing them to work on their ball skills, learn to adjust to the pass, and catch in dozens of different ways. The end result: Receivers get literally thousands more productive reps than players at any other position by the time they reach college football.

"Catch radius” is the area in which a QB can throw the ball and confidently expect his receiver to snag it, and in recent years, the only thing that’s grown faster than the term’s buzzword status is receivers’ actual catch radius, which now seems to be the entire field.

The 7-on-7 generation entered the league with advanced pass-catching abilities, and now they’re using NFL training methods to enhance their already well-oiled skills and take their acrobatics to new heights. Nate Burleson, a 1,000-yard receiver in 2004 who played alongside Randy Moss and Calvin Johnson and is now an NFL Network analyst, said that in his day, everyone but the game’s elite was dissuaded by coaches from showing flair while catching, especially in practice. Practicing for unusual situations like one-handed catches or catches from the ground was not part of the routine. Now, players are so advanced when they hit the pros that coaches expect, and encourage, the exceptional.

“Guys are practicing every scenario — catching the ball jumping up and down, laying on the ground and trying to catch it,” Burleson said. He mentioned that in practice, Pittsburgh’s Brown catches the ball while a trainer “aggressively yanks on his arm. He’s simulating the moment when you have to go up to catch when one of your arms is restricted. So that when it happens, you’ll be confident. In the past, receivers would have walked away, and you’d tell the coach, ‘I didn’t have my other hand,’ and the coach would say, ‘All right, cool.’ Now, you do that to a wide receiver coach and he’ll say, ‘I don’t care, you should have caught it.’”

But no position has evolved more than wide receiver, which, thanks to a long list of converging forces, has become perhaps the most talent-stacked group in sports. That’s been palpable in this young NFL season, with dominant pass catchers buoying many top teams: Julio Jones delivered a 300-yard performance two weeks ago for the now 4–1 Falcons; Antonio Brown already has 447 yards and five touchdowns for the 4–1 Steelers; A.J. Green has been a rare bright spot for the flailing Bengals; and the list goes on.

Saying that we’re in a golden generation of wide receivers would be a gross understatement. We’re firmly in an era when, from the youth football level on up, nearly every trend in the past decade has favored receivers. And there’s no evidence that the talent gap between wideouts and other positions will close anytime soon. (...)

Saying that we’re in a golden generation of wide receivers would be a gross understatement. We’re firmly in an era when, from the youth football level on up, nearly every trend in the past decade has favored receivers. And there’s no evidence that the talent gap between wideouts and other positions will close anytime soon. (...)“There’s no doubt the game started changing in the early 2000s,” said Todd Watson, Julio Jones’s former coach at Alabama’s Foley High School and the current director of football operations at Troy University. “The game shifted from ground-and-pound to spread.” Every kid, Watson said, went from wanting to play running back in youth football to wanting to be involved in the passing game.

Watson, who arrived at Foley in 2005 after Jones’s freshman season, witnessed this firsthand: Jones was playing safety and running back when he started his high school career. Watson said that if Jones had played in an earlier era, he may have been instructed to bulk up and play defensive end. High school and youth football teams used to be based on the running game and defense, and a 6-foot-3, 220-pound athlete like Jones could excel at so many important positions that he rarely made it to the world of receiving, but that position gained importance due to schematic changes in the game. The proliferation of the spread offense, which began in the 1990s and exploded in the next decade, created a world where, for the first time, most high school teams needed a dominant receiver — and opted to put their best athletes there.

The explosion of that offense coincided with a change in routine, Watson said: “Kids in a small towns in America were working all summer. But during Julio’s time, it became the norm to train year-round.”

Shortly after the spread took off, spring and summer leagues boomed at the high school level, with seven players facing off on each side of the ball. Watson said players were looking for more ways to compete in the off months, and these 7-on-7 camps filled a big need. Powerhouse high schools like Hoover High School in Alabama hosted tournaments. Players traveled their regions to find leagues, some of which are run by high schools, some by independent companies. All have one thing in common: Their reliance on passing helps receivers improve.

The 7-on-7 concept is fairly straightforward: a 40-yard field, no tackling, no pads, and very little live-football action. There’s no pressure on quarterbacks. Defenses can’t tackle, lay a hit to break up a pass, or shed blockers. Receiver is, by far, the position with the 7-on-7 skill set that most closely resembles what those players will eventually need to succeed in a game. In a confined space, receivers aren’t able to rely as fully on their natural speed, forcing them to work on their ball skills, learn to adjust to the pass, and catch in dozens of different ways. The end result: Receivers get literally thousands more productive reps than players at any other position by the time they reach college football.

"Catch radius” is the area in which a QB can throw the ball and confidently expect his receiver to snag it, and in recent years, the only thing that’s grown faster than the term’s buzzword status is receivers’ actual catch radius, which now seems to be the entire field.

The 7-on-7 generation entered the league with advanced pass-catching abilities, and now they’re using NFL training methods to enhance their already well-oiled skills and take their acrobatics to new heights. Nate Burleson, a 1,000-yard receiver in 2004 who played alongside Randy Moss and Calvin Johnson and is now an NFL Network analyst, said that in his day, everyone but the game’s elite was dissuaded by coaches from showing flair while catching, especially in practice. Practicing for unusual situations like one-handed catches or catches from the ground was not part of the routine. Now, players are so advanced when they hit the pros that coaches expect, and encourage, the exceptional.

“Guys are practicing every scenario — catching the ball jumping up and down, laying on the ground and trying to catch it,” Burleson said. He mentioned that in practice, Pittsburgh’s Brown catches the ball while a trainer “aggressively yanks on his arm. He’s simulating the moment when you have to go up to catch when one of your arms is restricted. So that when it happens, you’ll be confident. In the past, receivers would have walked away, and you’d tell the coach, ‘I didn’t have my other hand,’ and the coach would say, ‘All right, cool.’ Now, you do that to a wide receiver coach and he’ll say, ‘I don’t care, you should have caught it.’”

by Kevin Clark, The Ringer | Read more:

Image: Doug Baldwin, Seahawks.com

‘I Will Not Smile. I Am Not Your Monkey.’

[ed. I can understand how women might consider this a form of microaggression (is that a term getting a workout this year, or what?), but at the same time I'd hazard a guess that most men would be flattered to have the same attention. Usually it's like we're transparent. I've had buddies and even strangers tell me on occasion to smile (or, 'lighten up'!) and my usual response has been to just shrug it off (or give them the finger). On the other hand, it seems any attempt at conversation with a woman immediately gets processed through a threat filter (you can almost see it happening before your eyes) and a lot of men simply avoid saying anything friendly, even if they'd like to. I guess the answer is to just not say anything complimentary (or otherwise) about another person's appearance. Nice weather we're having today, eh?]

In a previous note, a reader wondered “what might happen if one refuses to smile.” Here are some readers who did refuse—and then responded forcefully to the men who’d solicited their smiles. Sarah writes:

by Rosa Inocencio Smith, The Atlantic | Read more:

Image: Gonzalo Fuentes / Reuters

In a previous note, a reader wondered “what might happen if one refuses to smile.” Here are some readers who did refuse—and then responded forcefully to the men who’d solicited their smiles. Sarah writes:

We all have these stories, don’t we?

Long ago, I was out at a bar with some friends when a Nice Guy decided to be cute with me. My attention had wandered and this, apparently, was unacceptable. So Mr. Nice Guy grabbed me by both shoulders, shook me, and yelled “Hey! Smile!”

This happened a month or two after I had been sexually assaulted. I’ve never liked being touched without my consent, and that was particularly true at this point in my life. I reacted instinctively and pulled back to lay Mr. Nice Guy out flat. I stopped myself before my fist connected with his face, but—too late.

My negative reaction to his “just trying to be friendly!” act got me a torrent of anger and insults: I was a bitch, I should crawl back under my rock, I was (of course) fat and ugly, etc. He was ready to hit me when my male companions intervened. Mr. Nice Guy slunk away, only after he had shared his opinions about my looks and attitude with the men in my group.

I don’t believe for a minute that the problem in that little interaction was my attitude. I am certain that Mr. Nice Guy never would have pulled that stunt on a random male at the bar who seemed preoccupied, because he knew that doing so would get him punched in the face.Anne writes:

Picture this: I had just left the nursing home to visit my dying mother (who did not recognize me in her advanced stage of Alzheimer’s) and pulled into a restaurant to have a late breakfast before the long ride home. I am sitting at the table, reading a serious email from my sister about my mother's care and what the long-term plan was for my terminally ill father.

An older gentleman approached me and said, “Smile!” The rest of the dialogue went something like this:

“Excuse me?”

“You should smile. I saw you reading and you just look too serious.”

“I’m not reading anything funny.”

“Yes, but you are just too INTO it. I saw you through the window. You look mean, so I think if you would just smile it would make you feel better.”

“Sir, with all due respect, I will not smile. I am not your monkey and you have no right to comment on my countenance. I think, therefore, that you should walk away and mind your own business.”

His wife overheard this exchange and gave ME the stink eye.

I told my girlfriends about this, and they said, “Aww, he was just a harmless old man trying to flirt with you.” This made me more upset than being told to smile; my friends just didn’t get it. Did I really have to explain this?? It still angers me when I think about it. (...)To me, these stories illustrate part of why comments on smiles can be so insidious and so frustrating. To tell someone to smile is invasive. It’s a comment on personal circumstances, on the thoughts and feelings that person should be allowed to keep private. It’s rude in the same way it’s rude to comment on someone’s weight gain or scars or miscarriage or divorce. But a smile is the part of someone’s mood that gets presented to the public, so on its face (and I do intend that pun), the command to smile seems casual, innocuous. To reveal the very personal reasons why we might not feel like smiling can seem like a much more obvious breach of social norms. And the pressure to be polite, to not make a scene, is deeply ingrained in us from childhood.

by Rosa Inocencio Smith, The Atlantic | Read more:

Image: Gonzalo Fuentes / Reuters

Wednesday, October 12, 2016

The Alt-Right Was Conjured Out of Pearl Clutching and Media Attention

They say that its power comes from its name. That it can only exist so long as it’s spoken. And that, voice by voice, it will continue to grow, until it is too large to keep in a box, and then too large to keep in the house, and then too large to keep. A runaway monster, feeding on its own designation.

So begins the horror story that isn’t a story at all—but instead summarizes the rise of the alt-right, a nebulous political movement that simultaneously stands for xenophobic white nationalism and also for antagonizing those who take offense to xenophobic white nationalism.

The emergence of the alt-right isn’t confined to the alt-right itself, however. With each article condemning or attempting to explain the alt-right, with each Twitter exchange and Facebook conversation blasting or laughing at or lauding its behavior, the alt-right monster has grown, its success more a reflection of the reaction it has been able to elicit than the strength of its own participants’ voices. Specifically assessing journalists’ role in perpetuating the alt-right story, Chava Gourarie notes that, the more the movement was reported on, the more reporting journalists were required to do; to speak of the alt-right is to make it so they can’t not be discussed.

The emergence of the alt-right isn’t confined to the alt-right itself, however. With each article condemning or attempting to explain the alt-right, with each Twitter exchange and Facebook conversation blasting or laughing at or lauding its behavior, the alt-right monster has grown, its success more a reflection of the reaction it has been able to elicit than the strength of its own participants’ voices. Specifically assessing journalists’ role in perpetuating the alt-right story, Chava Gourarie notes that, the more the movement was reported on, the more reporting journalists were required to do; to speak of the alt-right is to make it so they can’t not be discussed.

It’s not difficult to see why people would be concerned. The alt-right embodies everything that goes bump on the internet in 2016. Not only do its members condemn—even actively antagonize—progressive calls for social justice, they do so with a knowing smirk, arguing that that they don’t actually mean the bigoted things they say, they’re just trying to freak out the normies.

Of course, whether extremism is sincere or—as in the case of Pepe, a frog meme conscripted into the alt-right’s cause—presented as some kind of joke, it is still extremism; as my co-author Ryan Milner and I argue of Pepe’s emergent bigotry, that is the message being communicated, and so that is the message, period.

And Pepe is just a drop in the bucket. Regardless of motivations, regardless of sincerity, the alt-right’s white supremacist cheerleading has emerged as a key factor in the presidential election. Two events in particular have ensured this ascendency.

The first was the alt-right’s racist harassment and subsequent hacking of Leslie Jones, a story Aja Romano describes as a “flashpoint of the alt-right’s escalating culture war.” One that also served as a flashpoint of the coverage the group would enjoy all summer, which journalists often, and not incorrectly, connected back to the election.

The second catalyst followed Hillary Clinton’s highly-publicized “alt-right speech” linking the group’s “God Emperor Trump” to white supremacy. Clinton’s speech was savvy in that it called Trump out for fanning the flames of bigotry, if not being an outright bigot himself. But it also provided the alt-right, and white nationalism more broadly, the largest platform it had ever enjoyed. The alt-right was, of course, “thrilled” with this attention, as their monster grew ever larger and more unwieldy.

The alt-right isn’t alone in this narrative. The loose hacking and trolling collective Anonymous emerged in a similar fashion. Given the amount of time that has passed since Anonymous first bubbled out of 4chan’s cauldron, I must specify: here I am referring specifically to Anonymous circa 2007-2010, a self-styled (and highly winking) “internet hate machine” interchangeable with 4chan’s /b/ board and synonymous with subcultural trolling. This is the Anonymous I explore in my first book, which I describe as existing in a “cybernetic feedback loop” with sensationalist corporate media. Anonymous would not have risen to such prominence, I argue, without sensationalist media—and Fox News in particular, as this infamous 2007 news clip attests—to simultaneously toot and condemn Anonymous’ horn. Their condemnation, of course, ultimately functioning as both advertisement and recruitment tool.

The connection between Anonymous and the alt-right doesn’t end there. As early as 2015, Jacob Siegal was noting the similarities between Anonymous and what would soon become known as the alt-right (at that point, the alt-right had yet to coalesce, though wisps of its eventual form permeate Siegal’s article).

It is impossible to know how many (if any) original Anons were swept into the alt-right fold. What is clear is that the alt-right pulls many of its in-jokes from 4chan’s persistently strong gravitational pull, for example the aforementioned Pepe. And many of the behaviors heralded by the alt-right—for example gaming post-debate polls or “shitposting” forums with racist pro-Trump memes—echo longstanding subcultural trolling tactics, like when trolling participants gamed the Time 100 list to favor 4chan founder Christopher “moot” Poole and cluttered more forums with more bigoted expression than can possibly be quantified.

The rhetorical and behavioral overlaps between early Anonymous and the alt-right help place both groups in context. But these nebulous collectives are most significantly linked through the conjuring process. In each case, previously insular communities were transformed into forces to be reckoned with. Into monsters, all through the repeated chanting of their name.

So begins the horror story that isn’t a story at all—but instead summarizes the rise of the alt-right, a nebulous political movement that simultaneously stands for xenophobic white nationalism and also for antagonizing those who take offense to xenophobic white nationalism.

The emergence of the alt-right isn’t confined to the alt-right itself, however. With each article condemning or attempting to explain the alt-right, with each Twitter exchange and Facebook conversation blasting or laughing at or lauding its behavior, the alt-right monster has grown, its success more a reflection of the reaction it has been able to elicit than the strength of its own participants’ voices. Specifically assessing journalists’ role in perpetuating the alt-right story, Chava Gourarie notes that, the more the movement was reported on, the more reporting journalists were required to do; to speak of the alt-right is to make it so they can’t not be discussed.

The emergence of the alt-right isn’t confined to the alt-right itself, however. With each article condemning or attempting to explain the alt-right, with each Twitter exchange and Facebook conversation blasting or laughing at or lauding its behavior, the alt-right monster has grown, its success more a reflection of the reaction it has been able to elicit than the strength of its own participants’ voices. Specifically assessing journalists’ role in perpetuating the alt-right story, Chava Gourarie notes that, the more the movement was reported on, the more reporting journalists were required to do; to speak of the alt-right is to make it so they can’t not be discussed.It’s not difficult to see why people would be concerned. The alt-right embodies everything that goes bump on the internet in 2016. Not only do its members condemn—even actively antagonize—progressive calls for social justice, they do so with a knowing smirk, arguing that that they don’t actually mean the bigoted things they say, they’re just trying to freak out the normies.

Of course, whether extremism is sincere or—as in the case of Pepe, a frog meme conscripted into the alt-right’s cause—presented as some kind of joke, it is still extremism; as my co-author Ryan Milner and I argue of Pepe’s emergent bigotry, that is the message being communicated, and so that is the message, period.

And Pepe is just a drop in the bucket. Regardless of motivations, regardless of sincerity, the alt-right’s white supremacist cheerleading has emerged as a key factor in the presidential election. Two events in particular have ensured this ascendency.

The first was the alt-right’s racist harassment and subsequent hacking of Leslie Jones, a story Aja Romano describes as a “flashpoint of the alt-right’s escalating culture war.” One that also served as a flashpoint of the coverage the group would enjoy all summer, which journalists often, and not incorrectly, connected back to the election.

The second catalyst followed Hillary Clinton’s highly-publicized “alt-right speech” linking the group’s “God Emperor Trump” to white supremacy. Clinton’s speech was savvy in that it called Trump out for fanning the flames of bigotry, if not being an outright bigot himself. But it also provided the alt-right, and white nationalism more broadly, the largest platform it had ever enjoyed. The alt-right was, of course, “thrilled” with this attention, as their monster grew ever larger and more unwieldy.

The alt-right isn’t alone in this narrative. The loose hacking and trolling collective Anonymous emerged in a similar fashion. Given the amount of time that has passed since Anonymous first bubbled out of 4chan’s cauldron, I must specify: here I am referring specifically to Anonymous circa 2007-2010, a self-styled (and highly winking) “internet hate machine” interchangeable with 4chan’s /b/ board and synonymous with subcultural trolling. This is the Anonymous I explore in my first book, which I describe as existing in a “cybernetic feedback loop” with sensationalist corporate media. Anonymous would not have risen to such prominence, I argue, without sensationalist media—and Fox News in particular, as this infamous 2007 news clip attests—to simultaneously toot and condemn Anonymous’ horn. Their condemnation, of course, ultimately functioning as both advertisement and recruitment tool.

The connection between Anonymous and the alt-right doesn’t end there. As early as 2015, Jacob Siegal was noting the similarities between Anonymous and what would soon become known as the alt-right (at that point, the alt-right had yet to coalesce, though wisps of its eventual form permeate Siegal’s article).

It is impossible to know how many (if any) original Anons were swept into the alt-right fold. What is clear is that the alt-right pulls many of its in-jokes from 4chan’s persistently strong gravitational pull, for example the aforementioned Pepe. And many of the behaviors heralded by the alt-right—for example gaming post-debate polls or “shitposting” forums with racist pro-Trump memes—echo longstanding subcultural trolling tactics, like when trolling participants gamed the Time 100 list to favor 4chan founder Christopher “moot” Poole and cluttered more forums with more bigoted expression than can possibly be quantified.

The rhetorical and behavioral overlaps between early Anonymous and the alt-right help place both groups in context. But these nebulous collectives are most significantly linked through the conjuring process. In each case, previously insular communities were transformed into forces to be reckoned with. Into monsters, all through the repeated chanting of their name.

by Whitney Phillips, Motherboard | Read more:

Image: uncredited

BMW Motorrad Vision Next 100

So what does the future of motorcycles hold?

At least according to BMW, it's a bike that has self-balancing systems to keep it upright both when standing (a boon for novice riders, on par with training wheels for bicycles) and in motion (beneficial for experienced riders who want erudite handling at high speed). Several systems—one BMW calls a “Digital Companion,” which offers riding advice and adjustment ideas to optimize the experience, and one called “The Visor,” which is a pair of glasses that span the entire field of vision and are controlled by eye movements—correlate to return active feedback about road conditions to the rider while adjusting the ride of the bike continuously depending on the rider’s driving style. (Sure beats today's motorcycle touchscreen technology.)

At least according to BMW, it's a bike that has self-balancing systems to keep it upright both when standing (a boon for novice riders, on par with training wheels for bicycles) and in motion (beneficial for experienced riders who want erudite handling at high speed). Several systems—one BMW calls a “Digital Companion,” which offers riding advice and adjustment ideas to optimize the experience, and one called “The Visor,” which is a pair of glasses that span the entire field of vision and are controlled by eye movements—correlate to return active feedback about road conditions to the rider while adjusting the ride of the bike continuously depending on the rider’s driving style. (Sure beats today's motorcycle touchscreen technology.)It’s meant to equal the driverless systems automakers also expect to be producing in cars by 2040 and beyond.

“The bike has the full range of connected data from its surroundings and a set of intelligent systems working in the background, so it knows exactly what lies ahead,” said Holger Hampf, BMW's head of user experience.

It also purports to use a novel matte black “flexframe” that's nubile enough to allow the bike to turn without the joints found on today’s motorcycles. The idea is that when a rider turns the handlebar, it adjusts the entire frame to change the direction of the bike; at low speeds only a slight input is required, while at high speeds it needs strong input to change course. This should increase the safety factor of riding a bike so a small twitch at 100 mph isn't going to shoot you in an unexpected new direction.

by Hannah Elliott, Bloomberg | Read more:

Image: BMW Group

Tuesday, October 11, 2016

Robots Will Replace Doctors, Lawyers, and Other Professionals

Faced with the claim that AI and robots are poised to replace most of today’s workforce, most mainstream professionals — doctors, lawyers, accountants, and so on — believe they will emerge largely unscathed. During our consulting work and at conferences, we regularly hear practitioners concede that routine work can be taken on by machines, but they maintain that human experts will always be needed for the tricky stuff that calls for judgment, creativity, and empathy.

Our research and analysis challenges the idea that these professionals will be spared. We expect that within decades the traditional professions will be dismantled, leaving most, but not all, professionals to be replaced by less-expert people, new types of experts, and high-performing systems.

We conducted around 100 interviews, not with mainstream professionals but with leaders and new providers in eight professional fields: health, law, education, audit, tax, consulting, journalism, architecture, and divinity. Our focus was on what has actually been achieved at the cutting edge. We also immersed ourselves in over 800 related sources — published books, internal reports, and online systems. We found plenty of evidence that radical change in professional work is already under way.

We conducted around 100 interviews, not with mainstream professionals but with leaders and new providers in eight professional fields: health, law, education, audit, tax, consulting, journalism, architecture, and divinity. Our focus was on what has actually been achieved at the cutting edge. We also immersed ourselves in over 800 related sources — published books, internal reports, and online systems. We found plenty of evidence that radical change in professional work is already under way.

There are more monthly visits to the WebMD network, a collection of health websites, than to all the doctors in the United States. Annually, in the world of disputes, 60 million disagreements among eBay traders are resolved using “online dispute resolution” rather than lawyers and judges — this is three times the number of lawsuits filed each year in the entire U.S. court system. The U.S. tax authorities in 2014 received electronic tax returns from almost 50 million people who had relied on online tax-preparation software rather than human tax professionals. At WikiHouse, an online community designed a house that could be “printed” and assembled for less than £50,000. In 2011 the Vatican granted the first digital imprimatur to an app called “Confession” which helps people prepare for confession.

We believe these are but a few early indicators of a fundamental shift in professional service. Within professional organizations (firms, schools, hospitals), we are seeing a move away from tailored, unique solutions for each client or patient towards the standardization of service. Increasingly, doctors are using checklists, lawyers rely on precedents, and consultants work with methodologies. More recently, there has been a shift to systematization, the use of technology to automate and sometimes transform the way that professional work is done — from workflow systems through to AI-based problem-solving. More fundamentally, once professional knowledge and expertise is systematized, it will then be made available online, often as a chargeable service, sometimes at no cost, and occasionally but increasingly on a commons basis, in the spirit of the open source movement. There are already many examples of online professional service.

The claim that the professions are immune to displacement by technology is usually based on two assumptions: that computers are incapable of exercising judgment or being creative or empathetic, and that these capabilities are indispensable in the delivery of professional service. The first problem with this position is empirical. As our research shows, when professional work is broken down into component parts, many of the tasks involved turn out to be routine and process-based. They do not in fact call for judgment, creativity, or empathy.

The second problem is conceptual. Insistence that the outcomes of professional advisers can only be achieved by sentient beings who are creative and empathetic usually rests on what we call the “AI fallacy” — the view that the only way to get machines to outperform the best human professionals will be to copy the way that these professionals work. The error here is not recognizing that human professionals are already being outgunned by a combination of brute processing power, big data, and remarkable algorithms. These systems do not replicate human reasoning and thinking. When systems beat the best humans at difficult games, when they predict the likely decisions of courts more accurately than lawyers, or when the probable outcomes of epidemics can be better gauged on the strength of past medical data than on medical science, we are witnessing the work of high-performing, unthinking machines.

by Richard Susskind and Daniel Susskind, HBR | Read more:

Image: uncredited

Our research and analysis challenges the idea that these professionals will be spared. We expect that within decades the traditional professions will be dismantled, leaving most, but not all, professionals to be replaced by less-expert people, new types of experts, and high-performing systems.

We conducted around 100 interviews, not with mainstream professionals but with leaders and new providers in eight professional fields: health, law, education, audit, tax, consulting, journalism, architecture, and divinity. Our focus was on what has actually been achieved at the cutting edge. We also immersed ourselves in over 800 related sources — published books, internal reports, and online systems. We found plenty of evidence that radical change in professional work is already under way.

We conducted around 100 interviews, not with mainstream professionals but with leaders and new providers in eight professional fields: health, law, education, audit, tax, consulting, journalism, architecture, and divinity. Our focus was on what has actually been achieved at the cutting edge. We also immersed ourselves in over 800 related sources — published books, internal reports, and online systems. We found plenty of evidence that radical change in professional work is already under way.There are more monthly visits to the WebMD network, a collection of health websites, than to all the doctors in the United States. Annually, in the world of disputes, 60 million disagreements among eBay traders are resolved using “online dispute resolution” rather than lawyers and judges — this is three times the number of lawsuits filed each year in the entire U.S. court system. The U.S. tax authorities in 2014 received electronic tax returns from almost 50 million people who had relied on online tax-preparation software rather than human tax professionals. At WikiHouse, an online community designed a house that could be “printed” and assembled for less than £50,000. In 2011 the Vatican granted the first digital imprimatur to an app called “Confession” which helps people prepare for confession.

We believe these are but a few early indicators of a fundamental shift in professional service. Within professional organizations (firms, schools, hospitals), we are seeing a move away from tailored, unique solutions for each client or patient towards the standardization of service. Increasingly, doctors are using checklists, lawyers rely on precedents, and consultants work with methodologies. More recently, there has been a shift to systematization, the use of technology to automate and sometimes transform the way that professional work is done — from workflow systems through to AI-based problem-solving. More fundamentally, once professional knowledge and expertise is systematized, it will then be made available online, often as a chargeable service, sometimes at no cost, and occasionally but increasingly on a commons basis, in the spirit of the open source movement. There are already many examples of online professional service.

The claim that the professions are immune to displacement by technology is usually based on two assumptions: that computers are incapable of exercising judgment or being creative or empathetic, and that these capabilities are indispensable in the delivery of professional service. The first problem with this position is empirical. As our research shows, when professional work is broken down into component parts, many of the tasks involved turn out to be routine and process-based. They do not in fact call for judgment, creativity, or empathy.

The second problem is conceptual. Insistence that the outcomes of professional advisers can only be achieved by sentient beings who are creative and empathetic usually rests on what we call the “AI fallacy” — the view that the only way to get machines to outperform the best human professionals will be to copy the way that these professionals work. The error here is not recognizing that human professionals are already being outgunned by a combination of brute processing power, big data, and remarkable algorithms. These systems do not replicate human reasoning and thinking. When systems beat the best humans at difficult games, when they predict the likely decisions of courts more accurately than lawyers, or when the probable outcomes of epidemics can be better gauged on the strength of past medical data than on medical science, we are witnessing the work of high-performing, unthinking machines.

by Richard Susskind and Daniel Susskind, HBR | Read more:

Image: uncredited

Amazon Wants to Get College Students Addicted to Prime

[ed. You've got to hand it to them, Amazon is always thinking ahead. Prime is a great idea and a pretty good deal.]