“Apocalypse” seems like a bit much. I thought that last fall when

Vanity Fair titled Nancy Jo Sales’s article on dating apps “

Tinder and the Dawn of the ‘Dating Apocalypse’” and I thought it again this month when Hinge, another dating app, advertised its relaunch with a site called “thedatingapocalypse.com,” borrowing the phrase from Sales’s article, which apparently caused the company shame and was partially responsible for their effort to become, as they put it, a “relationship app.”

Despite the difficulties of modern dating, if there is an imminent apocalypse, I believe it will be spurred by something else. I don’t believe technology has distracted us from real human connection. I don’t believe hookup culture has infected our brains and turned us into soulless sex-hungry swipe monsters. And yet. It doesn’t do to pretend that dating in the app era hasn’t changed.

The gay dating app Grindr launched in 2009. Tinder arrived in 2012, and nipping at its heels came other imitators and twists on the format, like Hinge (connects you with friends of friends), Bumble (women have to message first), and others. Older online dating sites like OKCupid now have apps as well. In 2016, dating apps are old news, just an increasingly normal way to look for love and sex. The question is not if they work, because they obviously can, but how well do they work? Are they effective and enjoyable to use? Are people able to use them to get what they want? Of course, results can vary depending on what it is people want—to hook up or have casual sex, to date casually, or to date as a way of actively looking for a relationship. (...)

Sales’s article focused heavily on the negative effects of easy, on-demand sex that hookup culture prizes and dating apps readily provide. And while no one is denying the existence of fuckboys, I hear far more complaints from people who are trying to find relationships, or looking to casually date, who just find that it’s not working, or that it’s much harder than they expected.“It only has to work once, theoretically. But it feels like you have to put in a lot of swiping to get one good date.”

“I think the whole selling point with dating apps is ‘Oh, it’s so easy to find someone,’ and now that I’ve tried it, I’ve realized that’s actually not the case at all,” says my friend Ashley Fetters, a 26-year-old straight woman who is an editor at

GQ in New York City.

The easiest way to meet people turns out to be a really labor-intensive and uncertain way of getting relationships. While the possibilities seem exciting at first, the effort, attention, patience, and resilience it requires can leave people frustrated and exhausted.

“It only has to work once, theoretically,” says Elizabeth Hyde, a 26-year-old bisexual law student in Indianapolis. Hyde has been using dating apps and sites on and off for six years. “But on the other hand, Tinder just doesn’t feel efficient. I’m pretty frustrated and annoyed with it because it feels like you have to put in a lot of swiping to get like one good date.”

I have a theory that this exhaustion is making dating apps worse at performing their function. When the apps were new, people were excited, and actively using them. Swiping “yes” on someone didn’t inspire the same excited queasiness that asking someone out in person does, but there was a fraction of that feeling when a match or a message popped up. Each person felt like a real possibility, rather than an abstraction.

The first Tinder date I ever went on, in 2014, became a six-month relationship. After that, my luck went downhill. In late 2014 and early 2015, I went on a handful of decent dates, some that led to more dates, some that didn’t—which is about what I feel it’s reasonable to expect from dating services. But in the past year or so, I’ve felt the gears slowly winding down, like a toy on the dregs of its batteries. I feel less motivated to message people, I get fewer messages from others than I used to, and the exchanges I do have tend to fizzle out before they become dates. The whole endeavor seems tired.

“I’m going to project a really bleak theory on you,” Fetters says. “What if everyone who was going to find a happy relationship on a dating app already did? Maybe everyone who’s on Tinder now are like the last people at the party trying to go home with someone.”

Now that the shine of novelty has worn off these apps, they aren’t fun or exciting anymore. They’ve become a normalized part of dating. There’s a sense that if you’re single, and you don’t want to be, you need to

do something to change that. If you just sit on your butt and wait to see if life delivers you love, then you have no right to complain.

“Other than trying to go to a ton of community events, or hanging out at bars—I’m not really big on bars—I don’t feel like there’s other stuff to necessarily do to meet people,” Hyde says. “So it’s almost like the only recourse other than just sort of sitting around waiting for luck to strike is dating apps.”

But then, if you get tired of the apps, or have a bad experience on them, it creates this ambivalence—should you stop doing this thing that makes you unhappy or keep trying in the hopes it might yield something someday? This tension may lead to people walking a middle path—lingering on the apps while not actively using them much. I can feel myself half-assing it sometimes, for just this reason. (...)

Whenever using a technology makes people unhappy, the question is always: Is it the technology’s fault, or is it ours? Is Twitter terrible, or is it just a platform terrible people have taken advantage of? Are dating apps exhausting because of some fundamental problem with the apps, or just because dating is always frustrating and disappointing? (...)

For this story I’ve spoken with people who’ve used all manner of dating apps and sites, with varied designs. And the majority of them expressed some level of frustration with the experience, regardless of which particular products they used.

I don’t think whatever the problem is can be solved by design. Let’s move on.

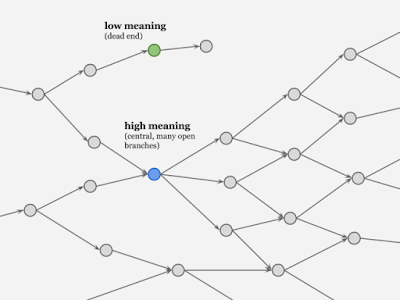

It's possible dating app users are suffering from the oft-discussed paradox of choice. This is the idea that having more choices, while it may seem good… is actually bad. In the face of too many options, people freeze up. They can’t decide which of the 30 burgers on the menu they want to eat, and they can’t decide which slab of meat on Tinder they want to date. And when they do decide, they tend to be less satisfied with their choices, just thinking about all the sandwiches and girlfriends they could have had instead.

The paralysis is real: According to a

2016 study of an unnamed dating app, 49 percent of people who message a match never receive a response. That’s in cases where someone messages at all. Sometimes, Hyde says, “You match with like 20 people and nobody ever says anything.”

“There’s an illusion of plentifulness,” as Fetters put it. “It makes it look like the world is full of more single, eager people than it probably is.”

Just knowing that the apps exist, even if you don’t use them, creates the sense that there’s an ocean of easily-accessible singles that you can dip a ladle into whenever you want.

“It does raise this question of: ‘What was the app delivering all along?’” Weigel says. “And I think there's a good argument to be made that the most important thing it delivers is not a relationship, but a certain sensation that there is possibility. And that's almost more important.”

Whether someone has had luck with dating apps or not, there’s always the chance that they

could. Perhaps the apps’ actual function is less important than what they signify as a totem: A pocket full of maybe that you can carry around to ward off despair.

Image: Chelsea Beck