Saturday, November 12, 2016

“Dear Diary: So I texted Julie and I told her that just because I’m hanging out with Linda a lot it doesn’t mean I’m not her friend anymore and she said she knows that but she just feels weird because she thinks that Linda doesn’t like her and because she thinks Linda and I have more in common, so I told her to stop worrying about what Linda thinks and she said fine but I could tell she was upset so I talked to Linda about it and she said she does like Julie and was trying really hard to be nice to her and when I told Julie what Linda had said she said she felt bad because she had been saying a lot of mean things about Linda. Anyway, I had a day off so I decided to go to the aquarium . . .”

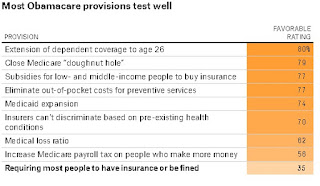

What Might Happen to Obamacare?

On the campaign trail, Donald Trump was clear that his priority for health care would be to repeal Obamacare. But after meeting with President Obama this week, he took a softer tone in an interview with The Wall Street Journal, saying that he’s looking into preserving some aspects of the law. Specifically, he expressed interest in two of the law’s most popular provisions: not allowing insurers to discriminate among buyers based on pre-existing health conditions and allowing young adults to stay on their parents’ health plans up to age 26. That still leaves a lot of unanswered questions about what he plans to do with the Affordable Care Act. (...)

Assuming that a reconciliation bill did pass, however, piecemeal changes would likely cause a lot of instability. The law is built on interlocking provisions; removing one puts pressure on others. That’s what happened when the Supreme Court made the Medicaid expansion optional for states, leaving 2.5 million people in states that chose not to expand in what has been called the Medicaid gap: too poor to be eligible for the marketplace subsidies but ineligible for Medicaid. Leaving in place the mandate for insurance companies to cover people with pre-existing conditions, as Trump said he’s considering, while getting rid of either the individual mandate — the requirement that people get insured — or the subsidies that motivate low-income healthy people to join the insurance rolls could also create instability in the insurance market. Without the necessary mix of healthy people in a plan to offset the costs of insuring people with pre-existing conditions, premiums rise, becoming unaffordable for everyone.

An estimated 22 million people would lose their insurance if Congress and Trump implemented the changes outlined in the most recent reconciliation bill. Even if Trump tries to hang onto the provisions he mentioned after meeting with Obama, it’s unclear what he might do to keep all those Americans insured. Looking at his campaign stump speeches, and proposed legislation from other Republicans, we can make some educated guesses about what might happen. (...)

Trump has said he wants to dismantle several key elements of the law, chief among them the individual mandate. He’s also said he’d like to use “block grants” that would provide a fixed sum, with fewer federal regulations, to states to fund Medicaid. It’s an idea that also features in House Speaker Paul Ryan’s health care proposal. That’s different from Medicaid expansion under the ACA, which requires that states cover everyone below 138 percent of the federal poverty line. It’s not clear how many of the millions of people who currently have Medicaid coverage under the ACA expansion would remain eligible for government assistance.

The individual mandate is a little more complicated. At one point, it was seen along most of the political spectrum as a promising way to reduce the number of uninsured people in the United States; requiring healthy people to sign up for coverage was supposed to ensure that premiums were affordable. The idea was originally floated by the conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation and was first brought to Congress by Republicans in the 1990s. The mandate has since become one of the most despised aspects of the law.

But there isn’t a clear policy proposal with bipartisan support for how to get more healthy people into the insurance market in the absence of an individual mandate and insurance subsidies. Trump has proposed creating high-risk pool insurance programs, essentially plans that people with pre-existing conditions can buy into. These types of plans existed in many states before the passage of the ACA and by design are not self-sustaining because members use significantly more health care than they can afford. That means they require significant federal dollars ($25 billion in the case of a plan from Ryan), which is one of the many reasons high-risk pools are divisive among Republican lawmakers.

Assuming that a reconciliation bill did pass, however, piecemeal changes would likely cause a lot of instability. The law is built on interlocking provisions; removing one puts pressure on others. That’s what happened when the Supreme Court made the Medicaid expansion optional for states, leaving 2.5 million people in states that chose not to expand in what has been called the Medicaid gap: too poor to be eligible for the marketplace subsidies but ineligible for Medicaid. Leaving in place the mandate for insurance companies to cover people with pre-existing conditions, as Trump said he’s considering, while getting rid of either the individual mandate — the requirement that people get insured — or the subsidies that motivate low-income healthy people to join the insurance rolls could also create instability in the insurance market. Without the necessary mix of healthy people in a plan to offset the costs of insuring people with pre-existing conditions, premiums rise, becoming unaffordable for everyone.

An estimated 22 million people would lose their insurance if Congress and Trump implemented the changes outlined in the most recent reconciliation bill. Even if Trump tries to hang onto the provisions he mentioned after meeting with Obama, it’s unclear what he might do to keep all those Americans insured. Looking at his campaign stump speeches, and proposed legislation from other Republicans, we can make some educated guesses about what might happen. (...)

Trump has said he wants to dismantle several key elements of the law, chief among them the individual mandate. He’s also said he’d like to use “block grants” that would provide a fixed sum, with fewer federal regulations, to states to fund Medicaid. It’s an idea that also features in House Speaker Paul Ryan’s health care proposal. That’s different from Medicaid expansion under the ACA, which requires that states cover everyone below 138 percent of the federal poverty line. It’s not clear how many of the millions of people who currently have Medicaid coverage under the ACA expansion would remain eligible for government assistance.

The individual mandate is a little more complicated. At one point, it was seen along most of the political spectrum as a promising way to reduce the number of uninsured people in the United States; requiring healthy people to sign up for coverage was supposed to ensure that premiums were affordable. The idea was originally floated by the conservative think tank the Heritage Foundation and was first brought to Congress by Republicans in the 1990s. The mandate has since become one of the most despised aspects of the law.

But there isn’t a clear policy proposal with bipartisan support for how to get more healthy people into the insurance market in the absence of an individual mandate and insurance subsidies. Trump has proposed creating high-risk pool insurance programs, essentially plans that people with pre-existing conditions can buy into. These types of plans existed in many states before the passage of the ACA and by design are not self-sustaining because members use significantly more health care than they can afford. That means they require significant federal dollars ($25 billion in the case of a plan from Ryan), which is one of the many reasons high-risk pools are divisive among Republican lawmakers.

Friday, November 11, 2016

Leonard Cohen

[ed. Another tribute (I guess?) to Leonard Cohen, using a clip my nephew Tony did for Armani glasses.]

Democrats, Trump, and the Ongoing, Dangerous Refusal to Learn the Lesson of Brexit

The parallels between the U.K.’s shocking approval of the Brexit referendum in June and the U.S.’s even more shocking election of Donald Trump as president Tuesday night are overwhelming. Elites (outside of populist right-wing circles) aggressively unified across ideological lines in opposition to both. Supporters of Brexit and Trump were continually maligned by the dominant media narrative (validly or otherwise) as primitive, stupid, racist, xenophobic, and irrational. In each case, journalists who spend all day chatting with one another on Twitter and congregating in exclusive social circles in national capitals — constantly re-affirming their own wisdom in an endless feedback loop — were certain of victory. Afterward, the elites whose entitlement to prevail was crushed devoted their energies to blaming everyone they could find except for themselves, while doubling down on their unbridled contempt for those who defied them, steadfastly refusing to examine what drove their insubordination.

The indisputable fact is that prevailing institutions of authority in the West, for decades, have relentlessly and with complete indifference stomped on the economic welfare and social security of hundreds of millions of people. While elite circles gorged themselves on globalism, free trade, Wall Street casino gambling, and endless wars (wars that enriched the perpetrators and sent the poorest and most marginalized to bear all their burdens), they completely ignored the victims of their gluttony, except when those victims piped up a bit too much — when they caused a ruckus — and were then scornfully condemned as troglodytes who were the deserved losers in the glorious, global game of meritocracy.

The indisputable fact is that prevailing institutions of authority in the West, for decades, have relentlessly and with complete indifference stomped on the economic welfare and social security of hundreds of millions of people. While elite circles gorged themselves on globalism, free trade, Wall Street casino gambling, and endless wars (wars that enriched the perpetrators and sent the poorest and most marginalized to bear all their burdens), they completely ignored the victims of their gluttony, except when those victims piped up a bit too much — when they caused a ruckus — and were then scornfully condemned as troglodytes who were the deserved losers in the glorious, global game of meritocracy.

That message was heard loud and clear. The institutions and elite factions that have spent years mocking, maligning, and pillaging large portions of the population — all while compiling their own long record of failure and corruption and destruction — are now shocked that their dictates and decrees go unheeded. But human beings are not going to follow and obey the exact people they most blame for their suffering. They’re going to do exactly the opposite: purposely defy them and try to impose punishment in retaliation. Their instruments for retaliation are Brexit and Trump. Those are their agents, dispatched on a mission of destruction: aimed at a system and culture they regard — not without reason — as rife with corruption and, above all else, contempt for them and their welfare.

After the Brexit vote, I wrote an article comprehensively detailing these dynamics, which I won’t repeat here but hope those interested will read. The title conveys the crux: “Brexit Is Only the Latest Proof of the Insularity and Failure of Western Establishment Institutions.” That analysis was inspired by a short, incredibly insightful, and now more relevant than ever post-Brexit Facebook note by the Los Angeles Times’s Vincent Bevins, who wrote that “both Brexit and Trumpism are the very, very wrong answers to legitimate questions that urban elites have refused to ask for 30 years.” Bevins went on: “Since the 1980s the elites in rich countries have overplayed their hand, taking all the gains for themselves and just covering their ears when anyone else talks, and now they are watching in horror as voters revolt.”

For those who tried to remove themselves from the self-affirming, vehemently pro-Clinton elite echo chamber of 2016, the warning signs that Brexit screechingly announced were not hard to see. Two short passages from a Slate interview I gave in July summarized those grave dangers: that opinion-making elites were so clustered, so incestuous, so far removed from the people who would decide this election — so contemptuous of them — that they were not only incapable of seeing the trends toward Trump but were unwittingly accelerating those trends with their own condescending, self-glorifying behavior.

Like most everyone else who saw the polling data and predictive models of the media’s self-proclaimed data experts, I long believed Clinton would win, but the reasons why she very well could lose were not hard to see. The warning lights were flashing in neon for a long time, but they were in seedy places that elites studiously avoid. The few people who purposely went to those places and listened, such as Chris Arnade, saw and heard them loud and clear. The ongoing failure to take heed of this intense but invisible resentment and suffering guarantees that it will fester and strengthen. This was the last paragraph of my July article on the Brexit fallout:

1. Democrats have already begun flailing around trying to blame anyone and everyone they can find — everyone except themselves — for last night’s crushing defeat of their party.

You know the drearily predictable list of their scapegoats: Russia, WikiLeaks, James Comey, Jill Stein, Bernie Bros, The Media, news outlets (including, perhaps especially, The Intercept) that sinned by reporting negatively on Hillary Clinton. Anyone who thinks that what happened last night in places like Ohio, Pennsylvania, Iowa, and Michigan can be blamed on any of that is drowning in self-protective ignorance so deep that it’s impossible to express in words.

When a political party is demolished, the principal responsibility belongs to one entity: the party that got crushed. It’s the job of the party and the candidate, and nobody else, to persuade the citizenry to support them and find ways to do that. Last night, the Democrats failed, resoundingly, to do that, and any autopsy or liberal think piece or pro-Clinton pundit commentary that does not start and finish with their own behavior is one that is inherently worthless.

Put simply, Democrats knowingly chose to nominate a deeply unpopular, extremely vulnerable, scandal-plagued candidate, who — for very good reason — was widely perceived to be a protector and beneficiary of all the worst components of status quo elite corruption. It’s astonishing that those of us who tried frantically to warn Democrats that nominating Hillary Clinton was a huge and scary gamble — that all empirical evidence showed that she could lose to anyone and Bernie Sanders would be a much stronger candidate, especially in this climate — are now the ones being blamed: by the very same people who insisted on ignoring all that data and nominating her anyway.

But that’s just basic blame shifting and self-preservation. Far more significant is what this shows about the mentality of the Democratic Party. Just think about who they nominated: someone who — when she wasn’t dining with Saudi monarchs and being feted in Davos by tyrants who gave million-dollar checks — spent the last several years piggishly running around to Wall Street banks and major corporations cashing in with $250,000 fees for 45-minute secret speeches even though she had already become unimaginably rich with book advances while her husband already made tens of millions playing these same games. She did all that without the slightest apparent concern for how that would feed into all the perceptions and resentments of her and the Democratic Party as corrupt, status quo-protecting, aristocratic tools of the rich and powerful: exactly the worst possible behavior for this post-2008-economic-crisis era of globalism and destroyed industries.

It goes without saying that Trump is a sociopathic con artist obsessed with personal enrichment: the opposite of a genuine warrior for the downtrodden. That’s too obvious to debate. But, just as Obama did so powerfully in 2008, he could credibly run as an enemy of the D.C. and Wall Street system that has steamrolled over so many people, while Hillary Clinton is its loyal guardian, its consummate beneficiary.

Trump vowed to destroy the system that elites love (for good reason) and the masses hate (for equally good reason), while Clinton vowed to manage it more efficiently. That, as Matt Stoller’s indispensable article in The Atlantic three weeks ago documented, is the conniving choice the Democratic Party made decades ago: to abandon populism and become the party of technocratically proficient, mildly benevolent managers of elite power. Those are the cynical, self-interested seeds they planted, and now the crop has sprouted.

The indisputable fact is that prevailing institutions of authority in the West, for decades, have relentlessly and with complete indifference stomped on the economic welfare and social security of hundreds of millions of people. While elite circles gorged themselves on globalism, free trade, Wall Street casino gambling, and endless wars (wars that enriched the perpetrators and sent the poorest and most marginalized to bear all their burdens), they completely ignored the victims of their gluttony, except when those victims piped up a bit too much — when they caused a ruckus — and were then scornfully condemned as troglodytes who were the deserved losers in the glorious, global game of meritocracy.

The indisputable fact is that prevailing institutions of authority in the West, for decades, have relentlessly and with complete indifference stomped on the economic welfare and social security of hundreds of millions of people. While elite circles gorged themselves on globalism, free trade, Wall Street casino gambling, and endless wars (wars that enriched the perpetrators and sent the poorest and most marginalized to bear all their burdens), they completely ignored the victims of their gluttony, except when those victims piped up a bit too much — when they caused a ruckus — and were then scornfully condemned as troglodytes who were the deserved losers in the glorious, global game of meritocracy.That message was heard loud and clear. The institutions and elite factions that have spent years mocking, maligning, and pillaging large portions of the population — all while compiling their own long record of failure and corruption and destruction — are now shocked that their dictates and decrees go unheeded. But human beings are not going to follow and obey the exact people they most blame for their suffering. They’re going to do exactly the opposite: purposely defy them and try to impose punishment in retaliation. Their instruments for retaliation are Brexit and Trump. Those are their agents, dispatched on a mission of destruction: aimed at a system and culture they regard — not without reason — as rife with corruption and, above all else, contempt for them and their welfare.

After the Brexit vote, I wrote an article comprehensively detailing these dynamics, which I won’t repeat here but hope those interested will read. The title conveys the crux: “Brexit Is Only the Latest Proof of the Insularity and Failure of Western Establishment Institutions.” That analysis was inspired by a short, incredibly insightful, and now more relevant than ever post-Brexit Facebook note by the Los Angeles Times’s Vincent Bevins, who wrote that “both Brexit and Trumpism are the very, very wrong answers to legitimate questions that urban elites have refused to ask for 30 years.” Bevins went on: “Since the 1980s the elites in rich countries have overplayed their hand, taking all the gains for themselves and just covering their ears when anyone else talks, and now they are watching in horror as voters revolt.”

For those who tried to remove themselves from the self-affirming, vehemently pro-Clinton elite echo chamber of 2016, the warning signs that Brexit screechingly announced were not hard to see. Two short passages from a Slate interview I gave in July summarized those grave dangers: that opinion-making elites were so clustered, so incestuous, so far removed from the people who would decide this election — so contemptuous of them — that they were not only incapable of seeing the trends toward Trump but were unwittingly accelerating those trends with their own condescending, self-glorifying behavior.

Like most everyone else who saw the polling data and predictive models of the media’s self-proclaimed data experts, I long believed Clinton would win, but the reasons why she very well could lose were not hard to see. The warning lights were flashing in neon for a long time, but they were in seedy places that elites studiously avoid. The few people who purposely went to those places and listened, such as Chris Arnade, saw and heard them loud and clear. The ongoing failure to take heed of this intense but invisible resentment and suffering guarantees that it will fester and strengthen. This was the last paragraph of my July article on the Brexit fallout:

Instead of acknowledging and addressing the fundamental flaws within themselves, [elites] are devoting their energies to demonizing the victims of their corruption, all in order to delegitimize those grievances and thus relieve themselves of responsibility to meaningfully address them. That reaction only serves to bolster, if not vindicate, the animating perceptions that these elite institutions are hopelessly self-interested, toxic, and destructive and thus cannot be reformed but rather must be destroyed. That, in turn, only ensures there will be many more Brexits, and Trumps, in our collective future.Beyond the Brexit analysis, there are three new points from last night’s results that I want to emphasize, as they are unique to the 2016 U.S. election and, more importantly, illustrate the elite pathologies that led to all of this:

1. Democrats have already begun flailing around trying to blame anyone and everyone they can find — everyone except themselves — for last night’s crushing defeat of their party.

You know the drearily predictable list of their scapegoats: Russia, WikiLeaks, James Comey, Jill Stein, Bernie Bros, The Media, news outlets (including, perhaps especially, The Intercept) that sinned by reporting negatively on Hillary Clinton. Anyone who thinks that what happened last night in places like Ohio, Pennsylvania, Iowa, and Michigan can be blamed on any of that is drowning in self-protective ignorance so deep that it’s impossible to express in words.

When a political party is demolished, the principal responsibility belongs to one entity: the party that got crushed. It’s the job of the party and the candidate, and nobody else, to persuade the citizenry to support them and find ways to do that. Last night, the Democrats failed, resoundingly, to do that, and any autopsy or liberal think piece or pro-Clinton pundit commentary that does not start and finish with their own behavior is one that is inherently worthless.

Put simply, Democrats knowingly chose to nominate a deeply unpopular, extremely vulnerable, scandal-plagued candidate, who — for very good reason — was widely perceived to be a protector and beneficiary of all the worst components of status quo elite corruption. It’s astonishing that those of us who tried frantically to warn Democrats that nominating Hillary Clinton was a huge and scary gamble — that all empirical evidence showed that she could lose to anyone and Bernie Sanders would be a much stronger candidate, especially in this climate — are now the ones being blamed: by the very same people who insisted on ignoring all that data and nominating her anyway.

But that’s just basic blame shifting and self-preservation. Far more significant is what this shows about the mentality of the Democratic Party. Just think about who they nominated: someone who — when she wasn’t dining with Saudi monarchs and being feted in Davos by tyrants who gave million-dollar checks — spent the last several years piggishly running around to Wall Street banks and major corporations cashing in with $250,000 fees for 45-minute secret speeches even though she had already become unimaginably rich with book advances while her husband already made tens of millions playing these same games. She did all that without the slightest apparent concern for how that would feed into all the perceptions and resentments of her and the Democratic Party as corrupt, status quo-protecting, aristocratic tools of the rich and powerful: exactly the worst possible behavior for this post-2008-economic-crisis era of globalism and destroyed industries.

It goes without saying that Trump is a sociopathic con artist obsessed with personal enrichment: the opposite of a genuine warrior for the downtrodden. That’s too obvious to debate. But, just as Obama did so powerfully in 2008, he could credibly run as an enemy of the D.C. and Wall Street system that has steamrolled over so many people, while Hillary Clinton is its loyal guardian, its consummate beneficiary.

Trump vowed to destroy the system that elites love (for good reason) and the masses hate (for equally good reason), while Clinton vowed to manage it more efficiently. That, as Matt Stoller’s indispensable article in The Atlantic three weeks ago documented, is the conniving choice the Democratic Party made decades ago: to abandon populism and become the party of technocratically proficient, mildly benevolent managers of elite power. Those are the cynical, self-interested seeds they planted, and now the crop has sprouted.

by Glenn Greenwald, The Intercept | Read more:

Image: via:

Book Review: House of God

[ed. I had never heard of The House of God until this review, but it has its own Wikipedia page and anything Scott Alexander at SSC recommends is worth investigating. Despite its age, much of it still sounds relevant.]

I’m not a big fan of war movies. I liked the first few I watched. It was all downhill from there. They all seem so similar. The Part Where You Bond With Your Squadmates. The Part Where Your Gruff Sergeant Turns Out To Have A Heart After All. The Part Where Your Friend Dies But You Have To Keep Going Anyway. The Part That Consists Of A Stirring Speech.

The problem is that war is very different from everything else, but very much like itself.

The problem is that war is very different from everything else, but very much like itself.

When I lived in Japan, I had a black neighbor who would always get told that she looked like Condoleezza Rice. She looked nothing like Condoleezza Rice. But if you’re Japanese, and the set of people you recognize includes ten million other Japanese people plus Condoleezza, then maybe all black women blur together into a vague Condoleezza-shaped blob. That’s how I am with war movies. War is so far from my usual experience that the differences among war movies don’t even register.

Medical internship is also very different from everything else but very much like itself. I already had two examples of it: Scrubs and my own experience as a medical intern (I preferred Scrubs). So when every single personin the medical field told me to read Samuel Shem’s House of God, I deferred. I deferred throughout my own internship, I deferred for another two years of residency afterwards. And then for some reason I finally picked it up a couple of days ago.

This was a heck of a book.

On some level it was as predictable as I expected. It hit all of the Important Internship Tropes, like The Part Where Your Attendings Are Cruel, The Part Where Your Patient Dies Because Of Something You Did, The Part Where You Get Camaraderie With Other Interns, The Part Where You First Realize You Are Actually Slightly Competent At Like One Thing And It Is The Best Feeling In The Universe, The Part Where You Realize How Pointless 99% Of The Medical System Is, The Part Where You Have Sex With Hot Nurses, et cetera.

All I can say is that it was really well done. The whole thing had a touch of magical realism, which turns out to be exactly the right genre for a story about medicine. Real medicine is absolutely magical realist. It’s a series of bizarre occurrences just on the edge of plausibility happening to incredibly strange people for life-and-death stakes, day after day after day, all within the context of the weirdest and most byzantine bureaucracy known to humankind. (...)

The story revolves around an obvious author-insert character, Roy Basch MD, who starts his internship year at a hospital called the House of God (apparently a fictionalized version of Beth Israel Hospital in Boston). He goes in with expectations to provide useful medical care to people with serious diseases. Instead, he finds gomers:

In the world of The House of God, medical intervention can only make patients worse:

I’m not a big fan of war movies. I liked the first few I watched. It was all downhill from there. They all seem so similar. The Part Where You Bond With Your Squadmates. The Part Where Your Gruff Sergeant Turns Out To Have A Heart After All. The Part Where Your Friend Dies But You Have To Keep Going Anyway. The Part That Consists Of A Stirring Speech.

The problem is that war is very different from everything else, but very much like itself.

The problem is that war is very different from everything else, but very much like itself.When I lived in Japan, I had a black neighbor who would always get told that she looked like Condoleezza Rice. She looked nothing like Condoleezza Rice. But if you’re Japanese, and the set of people you recognize includes ten million other Japanese people plus Condoleezza, then maybe all black women blur together into a vague Condoleezza-shaped blob. That’s how I am with war movies. War is so far from my usual experience that the differences among war movies don’t even register.

Medical internship is also very different from everything else but very much like itself. I already had two examples of it: Scrubs and my own experience as a medical intern (I preferred Scrubs). So when every single personin the medical field told me to read Samuel Shem’s House of God, I deferred. I deferred throughout my own internship, I deferred for another two years of residency afterwards. And then for some reason I finally picked it up a couple of days ago.

This was a heck of a book.

On some level it was as predictable as I expected. It hit all of the Important Internship Tropes, like The Part Where Your Attendings Are Cruel, The Part Where Your Patient Dies Because Of Something You Did, The Part Where You Get Camaraderie With Other Interns, The Part Where You First Realize You Are Actually Slightly Competent At Like One Thing And It Is The Best Feeling In The Universe, The Part Where You Realize How Pointless 99% Of The Medical System Is, The Part Where You Have Sex With Hot Nurses, et cetera.

All I can say is that it was really well done. The whole thing had a touch of magical realism, which turns out to be exactly the right genre for a story about medicine. Real medicine is absolutely magical realist. It’s a series of bizarre occurrences just on the edge of plausibility happening to incredibly strange people for life-and-death stakes, day after day after day, all within the context of the weirdest and most byzantine bureaucracy known to humankind. (...)

The story revolves around an obvious author-insert character, Roy Basch MD, who starts his internship year at a hospital called the House of God (apparently a fictionalized version of Beth Israel Hospital in Boston). He goes in with expectations to provide useful medical care to people with serious diseases. Instead, he finds gomers:

“Gomer is an acronym: Get Out of My Emergency Room. It’s what you want to say when one’s sent in from the nursing home at three A.M.”

“I think that’s kind of crass,” said Potts. “Some of us don’t feel that way about old people.”

“You think I don’t have a grandmother?” asked Fats indignantly. “I do, and she’s the cutest dearest, most wonderful old lady. Her matzoh balls float – you have to pin them down to eat them up. Under their force the soup levitates. We eat on ladders, scraping the food off the ceiling. I love…” The Fat Man had to stop, and dabbed the tears from his eyes, and then went on in a soft voice, “I love her very much.”

I thought of my grandfather. I loved him too.

“But gomers are not just dear old people,” said Fats. “Gomers are human beings who have lost what goes into being human beings. They want to die, and we will not let them. We’re cruel to the gomers, by saving them, and they’re cruel to us, by fighting tooth and nail against our trying to save them. They hurt us, we hurt them.” (...)In the world of The House of God, the primary form of medical treatment is the TURF – the excuse to get a patient out of your care and on to somebody else’s. If the psychiatrist can’t stand a certain patient any longer, she finds some trivial abnormality in their bloodwork and TURFs to the medical floor. But she knows that if the medical doctor doesn’t want one of his patients, then he can interpret a trivial patient comment like “Being sick is so depressing” as suicidal ideation and TURF to psychiatry. At 3 AM on a Friday night, every patient is terrible, the urge to TURF is overwhelming, and a hospital starts to seem like a giant wheel uncoupled from the rest of the world, Psychiatry TURFING to Medicine TURFING to Surgery TURFING to Neurosurgery TURFING to Neurology TURFING back to Psychiatry again. Surely some treatment must get done somewhere? But where? It becomes a legend, The Place Where Treatment Happens, hidden in some far-off hospital wing accessible only to the pure-hearted. This sort of Kafkaesque picture is how medical care feels, and the genius of The House of God is that it accentuates the reality just a little bit until its fictional world is almost as magical-realist as the real one. (...)

In the world of The House of God, medical intervention can only make patients worse:

Anna O. had started out on Jo’s service in perfect electrolyte balance, with each organ system working as perfectly as an 1878 model could. This, to my mind, included the brain, for wasn’t dementia a fail-safe and soothing oblivion of the machine to its own decay?

From being on the verge of a TURF back to the Hebrew House for the Incurables, as Anna knocked around the House of God in the steaming weeks of August, getting a skull film here and an LP there, she got worse, much worse. Given the stress of the dementia work-up, every organ system crumpled: in a domino progression the injection of radioactive dye for her brain scan shut down her kidneys, and the dye study of her kidneys overloaded her heart, and the medication for her heart made her vomit, which altered her electrolyte balance in a life-threatening way, which increased her dementia and shut down her bowel, which made her eligible for the bowel run, the cleanout for which dehydrated her and really shut down her tormented kidneys, which led to infection, the need for dialysis, and big-time complications of these big-time diseases. She and I both became exhausted, and she became very sick. Like the Yellow Man, she went through a phase of convulsing like a hooked tuna, and then went through a phase that was even more awesome, lying in bed deathly still, perhaps dying. I felt sad, for by this time, I liked her. I didn’t know what to do. I began to spend a good deal of time sitting with Anna, thinking.

The Fat Man was on call with me every third night as backup resident, and one night, searching for me to go to the ten o’clock meal, he found me with Anna, watching her trying to die.

“What the hell are you doing?” he asked.

I told him.

“Anna was on her way back to the Hebrew House, what happened – wait, don’t tell me. Jo decided to go all-out on her dementia, right?”

“Right. She looks like she’s going to die.”

“The only way she’ll die is if you murder her by doing what Jo says.”

“Yeah, but how can I do otherwise, with Jo breathing down my neck?”

“Easy. Do nothing with Anna, and hide it from Jo.”

“Hide it from Jo?”

“Sure. Continue the work-up in purely imaginary terms, buff the chart with the imaginary results of the imaginary tests, Anna will recover to her demented state, the work-up will show no treatable cause for it, and everybody’s happy. Nothing to it.”

“I’m not sure it’s ethical.”

“Is it ethical to murder this sweet gomere with your work-up?”

There was nothing I could say.” (...)House of God does a weird form of figure-ground inversion.

An example of what I mean, taken from politics: some people think of government as another name for the things we do together, like providing food to the hungry, or ensuring that old people have the health care they need. These people know that some politicians are corrupt, and sometimes the money actually goes to whoever’s best at demanding pork, and the regulations sometimes favor whichever giant corporation has the best lobbyists. But this is viewed as a weird disease of the body politic, something that can be abstracted away as noise in the system.

And then there are other people who think of government as a giant pork-distribution system, where obviously representatives and bureaucrats, incentivized in every way to support the forces that provide them with campaign funding and personal prestige, will take those incentives. Obviously they’ll use the government to crush their enemies. Sometimes this system also involves the hungry getting food and the elderly getting medical care, as an epiphenomenon of its pork-distribution role, but this isn’t particularly important and can be abstracted away as noise.

I think I can go back and forth between these two models when I need to, but it’s a weird switch of perspective, where the parts you view as noise in one model resolve into the essence of the other and vice versa.

And House of God does this to medicine.

Doctors use certain assumptions, like:

1. The patient wants to get better, but there are scientific limits that usually make this impossible

2. Medical treatment makes people healthier

3. Treatment is determined by medical need and expertise

But in House of God, the assumptions get inverted:

1. The patient wants to just die peacefully, but there are bureaucratic limits that usually make this impossible

2. Medical treatment makes people sicker

3. Treatment is determined by what will make doctors look good without having to do much work

Everybody knows that those first three assumptions aren’t always true. Yes, sometimes we prolong life in contravention of patients’ wishes. Sometimes people mistakenly receive unnecessary treatment that causes complications. And sometimes care suffers because of doctors’ scheduling issues. But it’s easy to abstract away to an ideal medicine based on benevolence and reason, and then view everything else as rare and unfortunate deviations from the norm.

House of God goes the whole way and does a full figure-ground inversion. The outliers become the norm; good care becomes the rare deviation. What’s horrifying is how convincing it is. Real medicine looks at least as much like the bizarro-world of House of God as it does the world of the popular imagination where doctors are always wise, diagnoses always correct, and patients always grateful.

And then there are other people who think of government as a giant pork-distribution system, where obviously representatives and bureaucrats, incentivized in every way to support the forces that provide them with campaign funding and personal prestige, will take those incentives. Obviously they’ll use the government to crush their enemies. Sometimes this system also involves the hungry getting food and the elderly getting medical care, as an epiphenomenon of its pork-distribution role, but this isn’t particularly important and can be abstracted away as noise.

I think I can go back and forth between these two models when I need to, but it’s a weird switch of perspective, where the parts you view as noise in one model resolve into the essence of the other and vice versa.

And House of God does this to medicine.

Doctors use certain assumptions, like:

1. The patient wants to get better, but there are scientific limits that usually make this impossible

2. Medical treatment makes people healthier

3. Treatment is determined by medical need and expertise

But in House of God, the assumptions get inverted:

1. The patient wants to just die peacefully, but there are bureaucratic limits that usually make this impossible

2. Medical treatment makes people sicker

3. Treatment is determined by what will make doctors look good without having to do much work

Everybody knows that those first three assumptions aren’t always true. Yes, sometimes we prolong life in contravention of patients’ wishes. Sometimes people mistakenly receive unnecessary treatment that causes complications. And sometimes care suffers because of doctors’ scheduling issues. But it’s easy to abstract away to an ideal medicine based on benevolence and reason, and then view everything else as rare and unfortunate deviations from the norm.

House of God goes the whole way and does a full figure-ground inversion. The outliers become the norm; good care becomes the rare deviation. What’s horrifying is how convincing it is. Real medicine looks at least as much like the bizarro-world of House of God as it does the world of the popular imagination where doctors are always wise, diagnoses always correct, and patients always grateful.

by Scott Alexander, Slate Star Codex | Read more:

Image: Amazon

Thursday, November 10, 2016

Workout Gear for When You’re Not Breaking a Sweat

[ed. No, not from the Onion.]

The athleisure spectrum now runs from workout clothes to off-duty weekend uniforms to “elevated” high fashion clothes — think Rihanna’s Fenty x Puma collection, characterized as Marie Antoinette-inspired streetwear — that is perfect for after dark. In a roundup of the recent Paris shows, Vogue.com decreed that the trend is now influencing all levels of fashion: “The athleisure effect can’t be denied.”

The mecca for athleisure is on lower Fifth Avenue from 17th Street to 23rd Street, in the Flatiron neighborhood. Stores there stock everything from basic black leggings to this season’s oversize bomber jackets. Bonus: Some of the stores have studios, a few offering free classes, and salespeople who are plugged in to the latest neighborhood fitness craze. It’s like finding out where the best powder is on the mountain from the cool ski locals while they are setting your bindings.

The mecca for athleisure is on lower Fifth Avenue from 17th Street to 23rd Street, in the Flatiron neighborhood. Stores there stock everything from basic black leggings to this season’s oversize bomber jackets. Bonus: Some of the stores have studios, a few offering free classes, and salespeople who are plugged in to the latest neighborhood fitness craze. It’s like finding out where the best powder is on the mountain from the cool ski locals while they are setting your bindings.Start at the southern end of the strip with Lululemon, which helped set off the athleisure tsunami, at the brand’s flagship store at 114 Fifth Avenue at 17th Street. It’s the company’s largest store in the United States, offering an overwhelming selection of its infamous leggings, mocked by some as overhyped and overpriced ($68 to $148) yet beloved by Luluhead stalwarts as flattering essentials.

The Lululemon salespeople are like legging sommeliers, patiently explaining the various fabric types, and suggesting associated activities for each — wicking materials for hot yoga, for example, or compression fabric for cycling, and lattice sides for barre class. Be warned that Lululemon sizes are not ego-boosting: If you are usually a size 6, you may need an 8. Still, the salespeople will work with you until they can honestly say that yes, it looks good.

And although it may sound like a “Saturday Night Live” parody, the store has a concierge who will point customers to nearby workout options, like Swerve, the hot new team-inspired cycling studio, or the latest array of workouts at Flex Studios (Pilates, barre and TRX), and then help book the classes. Downstairs, there is a studio called Hub Seventeen, which has classes, some free and some that cost $10 to $20, art shows and film screenings that can be booked online.

(While it will take you away from the area, a 20-minute walk to the Lululemon Lab at 50 Bond Street is worth the detour. The design team, working in full view in the back of the store, creates clothes with New Yorkers in mind — functional and mostly in dark and neutral palettes. This is class, not mass. Prices range from $60 for tops, to up to $450 for coats. The strap leggings have a horizontal slit at the knee, a fashion-statement riff on torn jeans that also allows for freedom of movement. It is one of only two Lab stores; the other is in Vancouver, British Columbia. The clothes are available only at the store, not online.)

Gap-owned Athleta, at 126 Fifth Avenue at 18th Street, does not push the envelope, and that can be a good thing. Mannequins are dressed in laid-back and doable options, such as leggings ($65 to $98) layered with a chunky long sweater and topped with down vests. A rotating roster of A-list teachers — like Dana Trixie Flynn from Laughing Lotus yoga — teaches classes in the beautiful studio downstairs. Classes are free. It is best to book online in advance because they fill up.

To flesh out the basic look, cross the street for hoodies, graphic tees and sunglasses at Zara, 101 Fifth Avenue at 17th Street, or H&M, 111 Fifth Avenue at 18th Street.

Tory Sport, 129 Fifth Avenue at 20th Street, is the athleisure line started by the designer Tory Burch in 2015. The ’70s-infused style is right in the modern groove: color-blocked, chevron-patterned and with track stripes in cutting-edge, sports-friendly fabrics. Framed vintage Sports Illustrated covers of greats like John McEnroe and Martina Navratilova set the vibe for the collection and the store, which has the feel of a sleek, retro Scandinavian ski chalet.

On a recent visit, a Tory Sport saleswoman inquired, “What sport are you into?” before pointing to the separate golf, tennis, running and studio lines. Her own current favorite, she said, was the killer workouts at Tone House in the neighboring Murray Hill area: “The hardest workout I’ve ever had.”

However, sport distinctions quickly seem irrelevant, as even a dedicated yogi on her way to check out the seamless leggings will stop short at the golf clothes, like the cunning short-sleeve crew neck sweater ($225) that has a contrasting ring collar and is made of “performance cashmere.” That’s right: cashmere that wicks. The “Coming and Going” category is a catchall for wardrobe staples officially intended for going to and from the studio. But these pieces, made from performance fabrics, are appropriate for work or for social gatherings. A convertible blazer with zip-in nylon dickey and hoodie is a nice twist on a classic ($365).

Bandier, a few blocks north at 164 Fifth Avenue at 22nd Street, is a multibrand shop, the place to check out this season’s mesh or perforated fabrics, graphic leggings, camouflage motorcycle (camo moto) jackets, cropped tops and oversize bomber jackets. These are club-worthy, the elevated end of the spectrum. The store is the real deal, so worth braving the brisk (or overwhelmed?) salespeople, including one who handed a customer a size small bomber jacket to try on, while waving off the idea of taking a medium for comparison purposes, with a definitive, “It’s supposed to be fitted.”

Bandier has attitude. Painted on the wall in a cheeky script is the message: “Take Care of Your Girls.” Upstairs at Studio B — “Where Fashion Fitness and Music Go to Play” — you can take classes like Stoked Shred, ModelFIT sculpt and Yoga for Bad People. Sign up online; prices range from $15 to $35. (...)

It is worth the cardio schlep up four flights of stairs at 25 West 23rd Street, just around the corner toward Sixth Avenue, to Y7 Studio, the self-proclaimed home of “Original Hip-Hop Yoga,” to check out the small retail space. Score a black graphic crop top or muscle shirt (“I’m Like / Hey / What’s Up / Let’s Flow,” or “Namastizzle,” $50) and a New York Yogis snapback hat ($40) for instant street cred.

by Mary Billard, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Stefania Curto for The New York TimesMakeover Mania

1. The Problem

In theory, the redesign begins with a problem. The problem might be specific or systemic or subjective. A logo makes a company’s image feel out of date. A familiar household object has been overtaken by new technology. A service has become too confusing for new users. And so on. The world is, after all, full of problems.

The human desire to solve problems fuels brand-new inventions too: The wheel, for example, eased conveyance significantly. But the redesign tends to address problems with, or caused by, dimensions of the human-designed world, and identifying such problems may be the designer’s most crucial skill. Redesigns fail when they address the wrong problem — or something that really wasn’t a problem in the first place. While progress may entail change, change does not necessarily guarantee progress. But a clever redesign, one that addresses the right problem in an intelligent fashion, improves the world, if just by a bit.

As an example in miniature of how the redesign is supposed to work, consider New York’s bike-share program. In 2014, Dani Simons, then the director of marketing for Citi Bike, visited a School of Visual Arts interaction-design class and presented it with a problem to solve. Citi Bike was selling plenty of annual memberships, but it was failing to attract enough “casual” riders, the sorts of one-off users who might rent a bike for just a day or a week. The class went into the field, observing and interviewing people at Citi Bike stations, and at their final meeting, the students presented Simons with their findings — and potential solutions.

As an example in miniature of how the redesign is supposed to work, consider New York’s bike-share program. In 2014, Dani Simons, then the director of marketing for Citi Bike, visited a School of Visual Arts interaction-design class and presented it with a problem to solve. Citi Bike was selling plenty of annual memberships, but it was failing to attract enough “casual” riders, the sorts of one-off users who might rent a bike for just a day or a week. The class went into the field, observing and interviewing people at Citi Bike stations, and at their final meeting, the students presented Simons with their findings — and potential solutions.

Simons was so impressed that she signed two students, Amy Wu and Luke Stern, to a three-month contract that summer. The two of them soon zeroed in on a particularly thorny design problem: the big, instructional decal on Citi Bike’s kiosks. Annual members used a key fob and had no reason to interact with the decal, but it was the gateway for casual users. Consisting mostly of text, the decals were dense and off-putting, especially to tourists uncomfortable with English. Some failed to understand that they were supposed to type in a code from a printed receipt to unlock a bike; instead, they tried to figure out how to insert the receipt itself into a slot on the docking station.

There was another, more prosaic reason that Stern and Wu focused on the decal: It was something they could actually change. Citi Bike is operated by a private firm, but New York’s Transportation Department oversees it, too, and the technology involves an external vendor. The decal, however, was produced in-house. So Stern and Wu proposed refashioning it, using a set of instructional pictograms loosely inspired by Ikea booklets. They tested several prototypes and endured baffled responses from Citi Bike users until eventually landing on a gridlike arrangement of visuals that people found intuitive. Simons and the Transportation Department signed off on a final version, and it was installed on the city’s 300-plus Citi Bike stations. Wu checked the service’s publicly available user data a month later and discovered that casual ridership had increased about 14 percent. “It was a little bit surreal,” Stern recalls. “We can actually make a difference.”

Indeed, this is the platonic ideal of the redesign: A designer sees a problem, proposes a solution, makes a difference. Such tidy narratives fuel a reigning ideology in which every object, symbol or pool of information is just another design problem awaiting some solution. The thermostat, the fire extinguisher, the toothbrush, the car dashboard — all have been redesigned, whether anybody was clamoring for their alteration or not.

This hunger for change has been a boon for firms like IDEO. Tim Brown, the company’s president and chief executive, has overseen IDEO’s steady expansion from product design to interactive and service design for businesses like Bank of America and Microsoft, and in more recent years even for municipalities and governments. He has been a vocal proponent of the idea that “design thinking” can be applied to just about any problem. “There are two takes on the redesign,” Brown says. “The glass-half-empty take on redesign is, ‘Oh, we’re unnecessarily redesigning a chair,’ or a lamp, or whatever.”

The glass-half-full take requires a broader perspective: “The need to redesign is really dependent on how fit for purpose the thing in question is,” Brown says. In his thinking, much of our world is built around systems designed to respond to the social structures and technologies of the industrial age. Everything from systems of education and health care to the design of cities and modes of transportation, he says, all trace their roots to a drastically different era and ought to be fundamentally rethought for the one we live in now. “I think we’ve potentially never been in a period of history where there are so many things that are no longer fit for purpose,” he says. “And therefore the idea of redesign is entirely appropriate, I think — even though it’s extremely difficult.”

2. What to Change

You don’t have to listen to Karim Rashid for very long to get a sense that he thinks pretty much every single manifestation of the built environment needs to be redesigned. Known for his colorful personal and professional style, he has had a long run as one of the most famous industrial designers in America. He believes design is a fundamentally social act that makes the world a better place. But it is also, he points out, a business. So in practice, most redesigns begin with a client; without one, not much happens. He has worked with many of them — on furniture, packaging, gadgets, housewares, luxury goods, even condos and hotels. But he has learned that even having a client does not guarantee that any given redesign will ever make it out of renderings and prototypes and into the real world. “People say I’m prolific,” he says. “Can you imagine if all the other stuff got to go to market?”

As Rashid sees it, so many of the things that surround us bear cumbersome vestiges of the past. “The world is full of this kind of kitsch history — history that has nothing to do with the world we live in now,” he says. He points to a redesign project of his that fizzled, a complete rethinking of the business-class tableware for Delta Air Lines. His proposal was bold: His bowls had sharp angles that echoed Delta’s triangular logo, his trays had subtle recesses that anchored dishes in place and his wineglasses skipped the stem in favor of a tapered shape with a wide base.

“The stem on a wineglass is meaningless,” Rashid says. He dismisses the conventional argument that it prevents the drinker’s hand from interfering with wine’s ideal temperature; to have the slightest such effect, he claims, you’d have to wrap your palm around the bowl for 20 straight minutes. The stem is actually a leftover artifact, he says, from centuries ago, when goblets made of metal had high stems to signal status and wealth. This design quirk remained after we switched to glass, Rashid says. Making wineglasses look a certain way because that’s how they have always looked is a classic example of privileging form over function. “I’m sitting in first class or business class on an airplane with turbulence,” Rashid says, “with a wineglass with a stem on it — do you understand? It’s so stupid, isn’t it?”

His proposed redesigns were striking, but they had to pass muster with the service-item maker, the flight attendants’ union and Delta itself — which ultimately declined to move forward with the concepts Rashid proposed. “It was all rejected,” he tells me, with a sigh. “Because it doesn’t look like domestic tableware.”

Rashid loves to “break archetypes,” in effect redesigning a whole object category. But the hurdles to doing so involve practicality as well as taste. More recently, he designed the Solarin mobile phone for Sirin Labs. It is equipped with extreme encryption capabilities and made with wealthy, privacy-obsessed customers in mind. It costs an eye-popping $12,000 and up. The client had a sky’s-the-limit attitude about imbuing the phone with a truly distinct form.

Rashid proposed an oval shape. “It would fit perfectly in your hand,” he says. His concept made it to prototype, and “everybody loved the oval phone.” But it turned out that only a handful of factories do smartphone glass assembly, and none were willing to retool an entire production line to accommodate a relatively small client. Moreover, existing operating systems are all designed to work in a grid format. The phone ended up with pronounced beveling at the edges, but was still fundamentally a rectangle. “I was so, so disappointed,” Rashid says. “I tried every trick.” Sounding almost wistful, he recalls a similar misadventure: an oval-shaped television set he designed for Samsung. “They showed it in some focus group, and it bombed,” he says, laughing. “People didn’t like the idea of an oval television. I have no idea why.”

3. What to Keep

I know why. And really, so does Rashid. As much as we are attracted to the new, we simultaneously cling to the familiar. This tension means that some redesigns — particularly in the realm of graphic design — can inspire surprisingly visceral public backlash. Earlier this year, for instance, Instagram updated its logo and app icon, simplifying the design and making it more colorful. The chorus of online moaning and mockery that followed grew so loud that it was actually reported on by The Times, which called it a “freak out.” Instagram didn’t budge, but a similar backlash in 2010 caused the Gap to retract plans for a new logo it had floated online. The University of California pulled back key elements of a redesign that met with a similarly furious response.

Probably the most notorious and consequential example involved Tropicana. In 2009, the brand rolled out a new look that included a full redesign of its familiar packaging and visual identity, dropping its orange-with-a-straw-in it logo — corny, perhaps, but very familiar — for a more stylish icon and a sans-serif type treatment. Fans howled online, but that probably mattered less than the reported 20 percent drop in retail sales. The redesign was withdrawn, and the brand went back to its old look.

Situations like this can unnerve clients, and this knowledge was certainly relevant to Mastercard when it decided this year to update its logo for the first time in more than 20 years. Raja Rajamannar, the global chief marketing and communications officer, says that the first parameter he gave his designer, Michael Bierut at Pentagram, “was not to mess things up.” The online crowd can get “pretty nasty,” he explains. “We don’t want to get mired in unnecessary controversy and negativity.”

This conservatism among clients can frustrate designers. “I was kind of brought up in this tradition that, you know, there’s nothing more inspiring than the blank slate, the open brief,” Bierut says. But over the years he has come to appreciate the challenge of “starting with a given,” particularly now.

“The last big period of redesign was the postwar era,” Bierut says. “There was this mania to make older companies look new and modern.” As a more corporate world emerged, the visual vernacular of mom-and-pop businesses looked quaint, and so design shifted from an emphasis on manufacturing things to selling more abstract forms of value. A railroad doesn’t run trains, the thinking went; it provides transportation — so instead of a representation of a locomotive, its more modern logo might rely on arrows and italic typography. More broadly, idiosyncratic or hand-drawn lettering gave way to stylized and minimal iconography and type treatments that projected far-flung and trustworthy power. “Corporate design was done as a command-and-control exercise,” he says, resulting in a master solution laid out in “a thick binder” prescribing how every branding element would appear.

“The last big period of redesign was the postwar era,” Bierut says. “There was this mania to make older companies look new and modern.” As a more corporate world emerged, the visual vernacular of mom-and-pop businesses looked quaint, and so design shifted from an emphasis on manufacturing things to selling more abstract forms of value. A railroad doesn’t run trains, the thinking went; it provides transportation — so instead of a representation of a locomotive, its more modern logo might rely on arrows and italic typography. More broadly, idiosyncratic or hand-drawn lettering gave way to stylized and minimal iconography and type treatments that projected far-flung and trustworthy power. “Corporate design was done as a command-and-control exercise,” he says, resulting in a master solution laid out in “a thick binder” prescribing how every branding element would appear.

By the ’80s and ’90s, that approach started to feel dated, suspicious and at odds with a vogue for more agile management theories. So in the last two decades, there has been a fresh wave of redesigns as companies have repositioned themselves in a more globalized, technologized marketplace. Mastercard is one of many examples of a company looking to update visual strategies designed with billboards and brick-and-mortar stores in mind for the age of social media and a transnational customer base.

Nevertheless, the specific dimensions of Mastercard’s “don’t mess it up” parameter included keeping the interlocking circles — one red, one yellow — that the brand has used for more than half a century. Bierut believes that this was wise: Unlike a book cover or a poster, a brand mark is “more like a building,” he says. “You don’t unveil it thinking it’s going to work once and then be on its way. It’s supposed to accrue value the longer it’s invested in.” The raw familiarity that builds up over years, which marketers refer to as “equity,” probably plays a bigger factor in our assessment of a supposedly great logo design than we realize. Bierut is tickled, for instance, by how many people seem to admire Target’s logo. “I can’t imagine if you went to your client whose name was Target and said, ‘I’ve got an idea,’ then you went away for a few weeks and came back with a circle with a dot in the middle, and an invoice,” he says. “The client would be skeptical — and the world at large would destroy you.”

For Mastercard, Pentagram got as creative as the brief allowed, offering dozens of yellow-and-red-circle variations — adding additional colors to suggest inclusivity, or a superminimal take presenting only the outlines of the interlocked rings. Rajamannar (and others at Mastercard, crosschecked by multiple rounds of market research) passed on those, opting for a treatment that amounted to a kind of reiteration of the existing mark. The colors became a little brighter, a set of stripes in their overlap was eliminated in favor of a single orange-y color and the name moved below the circles. Ultimately, in fact, the new symbol is designed to be able to stand alone, with no name at all; Rajamannar says testing conducted across 11 countries found 81 percent of respondents recognized the wordless version of the logo as Mastercard’s.

In short, the not-messing-it-up mission was deemed a success — and there was no notable backlash. “This kind of brand mark has become more ubiquitous than the designers of the ’60s and ’70s ever would have dreamed,” Bierut says, and that may explain a public interest in design that would have been a shock in that era. It should not be so surprising today; the design profession has been on a decades-long mission to have its work taken seriously across the culture. But now, having achieved what they wanted, many designers seem to wish the public would be more deferential — something Bierut finds amusing. “If designers claim to want people to be interested and invested in and care about design,” he says, “they sort of have to accept that interest on the terms of, you know, the audience.”

4. Where to Compromise

In 2011, Jamie Siminoff had just sold a start-up and was spending most of his days in his garage in Pacific Palisades, Calif., determined to come up with a new business concept. Tinkering with ideas including a gardening business and new conference-call technology, he soon became annoyed, because he could never hear his doorbell, and he kept missing visitors. So he “hacked together” a system that linked the bell to his phone. His wife told him that it was far more useful than the notions he was chasing in the garage. The idea evolved to include a camera and a motion detector — and thus the ability to monitor your front door from anywhere, with a smartphone, making the object as much about security as convenience.

The product he ended up with, Ring, is a good example of a broader phenomenon in the world of industrial design. The technology shifts that Brown and Rashid cite have quickened the pace of redesigns in more mundane, less grandiose ways. Thanks to the proliferation of cheap sensors, circuit boards, cameras and other components, practically every consumer good now seems susceptible to reinvention as a “smart object.” Even the path Siminoff traveled from concept to design was made easier by technology and start-up mania, first with the aid of a crowdfunding campaign, then with an unsuccessful but profile-raising appearance on “Shark Tank.”

Sometimes such a path results in a version of what the tech critic Evgeny Morozov calls “solutionism” — starting with a supposed breakthrough and then seeking out a supposed problem that it can hypothetically solve. And at times the presumed innovations in these tech-centric redesigns seem to run well ahead of their potential privacy and security pitfalls. (“Yes,” the tech site Motherboard reported last year, “your smart dildo can be hacked.”) But sometimes it results in a hit, like the widely celebrated update of the thermostat in internet-connected, app-controlled form created by the start-up Nest, which was ultimately bought by Google for $3.2 billion.

By his own account, Siminoff’s first stab at the product was a bit off. He called it Doorbot, and its look matched the geeky name: a vaguely sci-fi, curved object with a camera concealed by a spooky, bulbous protrusion. “That was the pride of the design,” Siminoff says now, laughing. He prototyped it in his garage with a couple of recent college graduates; none of them had a design background. The marketplace set him straight, he says: “No one wanted this big HAL 9000 thing on the front door.” He still believed in the object’s utility, but he realized he would need to redesign his redesign.

Siminoff found his way to Chris Loew, an industrial designer in Silicon Valley, with a long record in technology hardware; he worked on early versions of tablet products and spent 16 years at IDEO helping clients including Samsung and Oral-B. In more recent years he has been hired by a number of start-ups. Impressed by Siminoff, Loew also recognized the issues with Doorbot. “It was very gadgety,” he says, wryly. “You didn’t know if you were being shot with radiation or — you know, it’s not offensive, but you didn’t know what it was.” In short, it didn’t look like a doorbell, and even the most impressive technical capabilities have to be presented in a form that makes sense to the consumer.

In this case, that meant a design that resonated with basic home architecture. There were already serious technologized constraints: It had to accommodate a fairly large battery, a camera, a circuit board and a motion detector that required an opening of a specific size. And from a purely aesthetic perspective, the architectural setting imposed limits that might not apply to a free-standing product: Nobody really wants to tack a wild experiment in product design to a front door. Loew settled on a rectangular shape that would visually echo molding. “Everybody’s house is really just extruded shapes and planar shapes,” says Loew, who is now Ring’s lead product designer. The product comes in various finishes informed by classic door hardware, and is meant to be notable but not flashy.

The company has grown to 500 employees, with hundreds of thousands of installations already done. The only holdover from Doorbot is a circle around the button that glows blue when pressed.

In theory, the redesign begins with a problem. The problem might be specific or systemic or subjective. A logo makes a company’s image feel out of date. A familiar household object has been overtaken by new technology. A service has become too confusing for new users. And so on. The world is, after all, full of problems.

The human desire to solve problems fuels brand-new inventions too: The wheel, for example, eased conveyance significantly. But the redesign tends to address problems with, or caused by, dimensions of the human-designed world, and identifying such problems may be the designer’s most crucial skill. Redesigns fail when they address the wrong problem — or something that really wasn’t a problem in the first place. While progress may entail change, change does not necessarily guarantee progress. But a clever redesign, one that addresses the right problem in an intelligent fashion, improves the world, if just by a bit.

As an example in miniature of how the redesign is supposed to work, consider New York’s bike-share program. In 2014, Dani Simons, then the director of marketing for Citi Bike, visited a School of Visual Arts interaction-design class and presented it with a problem to solve. Citi Bike was selling plenty of annual memberships, but it was failing to attract enough “casual” riders, the sorts of one-off users who might rent a bike for just a day or a week. The class went into the field, observing and interviewing people at Citi Bike stations, and at their final meeting, the students presented Simons with their findings — and potential solutions.

As an example in miniature of how the redesign is supposed to work, consider New York’s bike-share program. In 2014, Dani Simons, then the director of marketing for Citi Bike, visited a School of Visual Arts interaction-design class and presented it with a problem to solve. Citi Bike was selling plenty of annual memberships, but it was failing to attract enough “casual” riders, the sorts of one-off users who might rent a bike for just a day or a week. The class went into the field, observing and interviewing people at Citi Bike stations, and at their final meeting, the students presented Simons with their findings — and potential solutions.Simons was so impressed that she signed two students, Amy Wu and Luke Stern, to a three-month contract that summer. The two of them soon zeroed in on a particularly thorny design problem: the big, instructional decal on Citi Bike’s kiosks. Annual members used a key fob and had no reason to interact with the decal, but it was the gateway for casual users. Consisting mostly of text, the decals were dense and off-putting, especially to tourists uncomfortable with English. Some failed to understand that they were supposed to type in a code from a printed receipt to unlock a bike; instead, they tried to figure out how to insert the receipt itself into a slot on the docking station.

There was another, more prosaic reason that Stern and Wu focused on the decal: It was something they could actually change. Citi Bike is operated by a private firm, but New York’s Transportation Department oversees it, too, and the technology involves an external vendor. The decal, however, was produced in-house. So Stern and Wu proposed refashioning it, using a set of instructional pictograms loosely inspired by Ikea booklets. They tested several prototypes and endured baffled responses from Citi Bike users until eventually landing on a gridlike arrangement of visuals that people found intuitive. Simons and the Transportation Department signed off on a final version, and it was installed on the city’s 300-plus Citi Bike stations. Wu checked the service’s publicly available user data a month later and discovered that casual ridership had increased about 14 percent. “It was a little bit surreal,” Stern recalls. “We can actually make a difference.”

Indeed, this is the platonic ideal of the redesign: A designer sees a problem, proposes a solution, makes a difference. Such tidy narratives fuel a reigning ideology in which every object, symbol or pool of information is just another design problem awaiting some solution. The thermostat, the fire extinguisher, the toothbrush, the car dashboard — all have been redesigned, whether anybody was clamoring for their alteration or not.

This hunger for change has been a boon for firms like IDEO. Tim Brown, the company’s president and chief executive, has overseen IDEO’s steady expansion from product design to interactive and service design for businesses like Bank of America and Microsoft, and in more recent years even for municipalities and governments. He has been a vocal proponent of the idea that “design thinking” can be applied to just about any problem. “There are two takes on the redesign,” Brown says. “The glass-half-empty take on redesign is, ‘Oh, we’re unnecessarily redesigning a chair,’ or a lamp, or whatever.”

The glass-half-full take requires a broader perspective: “The need to redesign is really dependent on how fit for purpose the thing in question is,” Brown says. In his thinking, much of our world is built around systems designed to respond to the social structures and technologies of the industrial age. Everything from systems of education and health care to the design of cities and modes of transportation, he says, all trace their roots to a drastically different era and ought to be fundamentally rethought for the one we live in now. “I think we’ve potentially never been in a period of history where there are so many things that are no longer fit for purpose,” he says. “And therefore the idea of redesign is entirely appropriate, I think — even though it’s extremely difficult.”

2. What to Change

You don’t have to listen to Karim Rashid for very long to get a sense that he thinks pretty much every single manifestation of the built environment needs to be redesigned. Known for his colorful personal and professional style, he has had a long run as one of the most famous industrial designers in America. He believes design is a fundamentally social act that makes the world a better place. But it is also, he points out, a business. So in practice, most redesigns begin with a client; without one, not much happens. He has worked with many of them — on furniture, packaging, gadgets, housewares, luxury goods, even condos and hotels. But he has learned that even having a client does not guarantee that any given redesign will ever make it out of renderings and prototypes and into the real world. “People say I’m prolific,” he says. “Can you imagine if all the other stuff got to go to market?”

As Rashid sees it, so many of the things that surround us bear cumbersome vestiges of the past. “The world is full of this kind of kitsch history — history that has nothing to do with the world we live in now,” he says. He points to a redesign project of his that fizzled, a complete rethinking of the business-class tableware for Delta Air Lines. His proposal was bold: His bowls had sharp angles that echoed Delta’s triangular logo, his trays had subtle recesses that anchored dishes in place and his wineglasses skipped the stem in favor of a tapered shape with a wide base.

“The stem on a wineglass is meaningless,” Rashid says. He dismisses the conventional argument that it prevents the drinker’s hand from interfering with wine’s ideal temperature; to have the slightest such effect, he claims, you’d have to wrap your palm around the bowl for 20 straight minutes. The stem is actually a leftover artifact, he says, from centuries ago, when goblets made of metal had high stems to signal status and wealth. This design quirk remained after we switched to glass, Rashid says. Making wineglasses look a certain way because that’s how they have always looked is a classic example of privileging form over function. “I’m sitting in first class or business class on an airplane with turbulence,” Rashid says, “with a wineglass with a stem on it — do you understand? It’s so stupid, isn’t it?”

His proposed redesigns were striking, but they had to pass muster with the service-item maker, the flight attendants’ union and Delta itself — which ultimately declined to move forward with the concepts Rashid proposed. “It was all rejected,” he tells me, with a sigh. “Because it doesn’t look like domestic tableware.”

Rashid loves to “break archetypes,” in effect redesigning a whole object category. But the hurdles to doing so involve practicality as well as taste. More recently, he designed the Solarin mobile phone for Sirin Labs. It is equipped with extreme encryption capabilities and made with wealthy, privacy-obsessed customers in mind. It costs an eye-popping $12,000 and up. The client had a sky’s-the-limit attitude about imbuing the phone with a truly distinct form.