There is a great deal of questioning now of the value of the humanities, those aptly named disciplines that make us consider what human beings have been, and are, and will be. Sometimes I think they should be renamed Big Data. These catastrophic wars that afflict so much of the world now surely bear more resemblance to the Hundred Years’ War or the Thirty Years’ War or the wars of Napoleon or World War I than they do to any expectations we have had about how history would unfold in the modern period, otherwise known as those few decades we call the postwar.

We have thought we were being cynical when we insisted that people universally are motivated by self-interest. Would God it were true! Hamlet’s rumination on the twenty thousand men going off to fight over a territory not large enough for them all to be buried in, going to their graves as if to their beds, shows a much sounder grasp of human behavior than this. It acknowledges a part of it that shows how absurdly optimistic our “cynicism” actually is. President Obama not long ago set off a kerfuffle among the press by saying that these firestorms of large-scale violence and destruction are not unique to Islamic culture or to the present time. This is simple fact, and it is also fair warning, if we hope to keep our own actions and reactions within something like civilized bounds. This would be one use of history. (...)

I am not speaking here of the usual and obvious malefactors, the blowhards on the radio and on cable television. I am speaking of the mainstream media, therefore of the institutions that educate most people of influence in America, including journalists. Our great universities, with their vast resources, their exhaustive libraries, look like a humanist’s dream. Certainly, with the collecting and archiving that has taken place in them over centuries, they could tell us much that we need to know. But there is pressure on them now to change fundamentally, to equip our young to be what the Fabians used to call “brain workers.” They are to be skilled laborers in the new economy, intellectually nimble enough to meet its needs, which we know will change constantly and unpredictably. I may simply have described the robots that will be better suited to this kind of existence, and with whom our optimized workers will no doubt be forced to compete, poor complex and distractible creatures that they will be still.

I am not speaking here of the usual and obvious malefactors, the blowhards on the radio and on cable television. I am speaking of the mainstream media, therefore of the institutions that educate most people of influence in America, including journalists. Our great universities, with their vast resources, their exhaustive libraries, look like a humanist’s dream. Certainly, with the collecting and archiving that has taken place in them over centuries, they could tell us much that we need to know. But there is pressure on them now to change fundamentally, to equip our young to be what the Fabians used to call “brain workers.” They are to be skilled laborers in the new economy, intellectually nimble enough to meet its needs, which we know will change constantly and unpredictably. I may simply have described the robots that will be better suited to this kind of existence, and with whom our optimized workers will no doubt be forced to compete, poor complex and distractible creatures that they will be still.

Why teach the humanities? Why study them? American universities are literally shaped around them and have been since their founding, yet the question is put in the bluntest form—what are they good for? If, for purposes of discussion, we date the beginning of the humanist movement to 1500, then, historically speaking, the West has flourished materially as well as culturally in the period of their influence. You may have noticed that the United States is always in an existential struggle with an imagined competitor. It may have been the cold war that instilled this habit in us. It may have been nineteenth-century nationalism, when America was coming of age and competition among the great powers of Europe drove world events. Whatever etiology is proposed for it, whatever excuse is made for it, however rhetorically useful it may be in certain contexts, the habit is deeply harmful, as it has been in Europe as well, when the competition involved the claiming and defending of colonies, as well as militarization that led to appalling wars.

The consequences of these things abide. We see and feel them every day. The standards that might seem to make societies commensurable are essentially meaningless, except when they are ominous. Insofar as we treat them as real, they mean that other considerations are put out of account. Who died in all those wars? The numbers lost assure us that there were artists and poets and mathematicians among them, and statesmen, though at best their circumstances may never have allowed them or us to realize their gifts. (...)

A great irony is at work in our historical moment. We are being encouraged to abandon our most distinctive heritage—in the name of self-preservation. The logic seems to go like this: To be as strong as we need to be we must have a highly efficient economy. Society must be disciplined, stripped down, to achieve this efficiency and to make us all better foot soldiers. The alternative is decadence, the eclipse of our civilization by one with more fire in its belly. We are to be prepared to think very badly of our antagonist, whichever one seems to loom at a given moment. It is a convention of modern literature, and of the going-on of talking heads and public intellectuals, to project what are said to be emerging trends into a future in which cultural, intellectual, moral, and economic decline will have hit bottom, more or less.

Somehow this kind of talk always seems brave and deep. The specifics concerning this abysmal future are vague—Britain will cease to be Britain, America will cease to be America, France will cease to be France, and so on, depending on which country happens to be the focus of Spenglerian gloom. The oldest literature of radical pessimism can be read as prophecy. Of course these three societies have changed profoundly in the last hundred years, the last fifty years, and few with any knowledge of history would admit to regretting the change. What is being invoked is the notion of a precious and unnamable essence, second nature to some, in the marrow of their bones, in effect. By this view others, whether they will or no, cannot understand or value it, and therefore they are a threat.

The definitions of “some” and “others” are unclear and shifting. In America, since we are an immigrant country, our “nativists” may be first- or second-generation Americans whose parents or grandparents were themselves considered suspect on these same grounds. It is almost as interesting as it is disheartening to learn that nativist rhetoric can have impact in a country where precious few can claim to be native in any ordinary sense. Our great experiment has yielded some valuable results—here a striking demonstration of the emptiness of such rhetoric, which is nevertheless loudly persistent in certain quarters in America, and which obviously continues to be influential in Britain and Europe.

Nativism is always aligned with an impulse or strategy to shape the culture with which it claims to have this privileged intimacy. It is urgently intent on identifying enemies and confronting them, and it is hostile to the point of loathing toward aspects of the society that are taken to show their influence. In other words, these lovers of country, these patriots, are wildly unhappy with the country they claim to love, and are bent on remaking it to suit their own preferences, which they feel no need to justify or even fully articulate. Neither do they feel any need to answer the objections of those who see their shaping and their disciplining as mutilation. (...)

What are we doing here, we professors of English? Our project is often dismissed as elitist. That word has a new and novel sting in American politics. This is odd, in a period uncharacteristically dominated by political dynasties. Apparently the slur doesn’t stick to those who show no sign of education or sophistication, no matter what their pedigree. Be that as it may. There is a fundamental slovenliness in much public discourse that can graft heterogeneous things together around a single word. There is justified alarm about the bizarre concentrations of wealth that have occurred globally, and the tiny fraction of the wealthiest one percent who have wildly disproportionate influence over the lives of the rest of us. They are called the elite, and so are those of us who encourage the kind of thinking that probably does make certain of the young less than ideal recruits to their armies of the employed.

If there is a point where the two meanings overlap, it would be in the fact that the teaching we do is what in America we have always called liberal education, education appropriate to free people, very much including those old Iowans who left the university to return to the hamlet or the farm. Now, in a country richer than any they could have imagined, we are endlessly told we must cede that humane freedom to a very uncertain promise of employability. It seems most unlikely that any oligarch foresees this choice as being forced on his or her own children. I note here that these criticisms and pressures are not brought to bear on our private universities, though most or all of them receive government money. Elitism in its classic sense is not being attacked but asserted and defended.

If I seem to have conceded an important point in saying that the humanities do not prepare ideal helots, economically speaking, I do not at all mean to imply that they are less than ideal for preparing capable citizens, imaginative and innovative contributors to a full and generous, and largely unmonetizable, national life. America has known long enough how to be a prosperous country, for all its deviations from the narrow path of economic rationalism. Empirically speaking, these errancies are highly compatible with our flourishing economically, if they are not a cause of it, which is more than we can know. The politicians who attack public higher education as too expensive have made it so for electoral or ideological reasons and could undo the harm with the stroke of a pen. They have created the crisis to which they hope to bring their draconian solutions.

We have thought we were being cynical when we insisted that people universally are motivated by self-interest. Would God it were true! Hamlet’s rumination on the twenty thousand men going off to fight over a territory not large enough for them all to be buried in, going to their graves as if to their beds, shows a much sounder grasp of human behavior than this. It acknowledges a part of it that shows how absurdly optimistic our “cynicism” actually is. President Obama not long ago set off a kerfuffle among the press by saying that these firestorms of large-scale violence and destruction are not unique to Islamic culture or to the present time. This is simple fact, and it is also fair warning, if we hope to keep our own actions and reactions within something like civilized bounds. This would be one use of history. (...)

I am not speaking here of the usual and obvious malefactors, the blowhards on the radio and on cable television. I am speaking of the mainstream media, therefore of the institutions that educate most people of influence in America, including journalists. Our great universities, with their vast resources, their exhaustive libraries, look like a humanist’s dream. Certainly, with the collecting and archiving that has taken place in them over centuries, they could tell us much that we need to know. But there is pressure on them now to change fundamentally, to equip our young to be what the Fabians used to call “brain workers.” They are to be skilled laborers in the new economy, intellectually nimble enough to meet its needs, which we know will change constantly and unpredictably. I may simply have described the robots that will be better suited to this kind of existence, and with whom our optimized workers will no doubt be forced to compete, poor complex and distractible creatures that they will be still.

I am not speaking here of the usual and obvious malefactors, the blowhards on the radio and on cable television. I am speaking of the mainstream media, therefore of the institutions that educate most people of influence in America, including journalists. Our great universities, with their vast resources, their exhaustive libraries, look like a humanist’s dream. Certainly, with the collecting and archiving that has taken place in them over centuries, they could tell us much that we need to know. But there is pressure on them now to change fundamentally, to equip our young to be what the Fabians used to call “brain workers.” They are to be skilled laborers in the new economy, intellectually nimble enough to meet its needs, which we know will change constantly and unpredictably. I may simply have described the robots that will be better suited to this kind of existence, and with whom our optimized workers will no doubt be forced to compete, poor complex and distractible creatures that they will be still.Why teach the humanities? Why study them? American universities are literally shaped around them and have been since their founding, yet the question is put in the bluntest form—what are they good for? If, for purposes of discussion, we date the beginning of the humanist movement to 1500, then, historically speaking, the West has flourished materially as well as culturally in the period of their influence. You may have noticed that the United States is always in an existential struggle with an imagined competitor. It may have been the cold war that instilled this habit in us. It may have been nineteenth-century nationalism, when America was coming of age and competition among the great powers of Europe drove world events. Whatever etiology is proposed for it, whatever excuse is made for it, however rhetorically useful it may be in certain contexts, the habit is deeply harmful, as it has been in Europe as well, when the competition involved the claiming and defending of colonies, as well as militarization that led to appalling wars.

The consequences of these things abide. We see and feel them every day. The standards that might seem to make societies commensurable are essentially meaningless, except when they are ominous. Insofar as we treat them as real, they mean that other considerations are put out of account. Who died in all those wars? The numbers lost assure us that there were artists and poets and mathematicians among them, and statesmen, though at best their circumstances may never have allowed them or us to realize their gifts. (...)

A great irony is at work in our historical moment. We are being encouraged to abandon our most distinctive heritage—in the name of self-preservation. The logic seems to go like this: To be as strong as we need to be we must have a highly efficient economy. Society must be disciplined, stripped down, to achieve this efficiency and to make us all better foot soldiers. The alternative is decadence, the eclipse of our civilization by one with more fire in its belly. We are to be prepared to think very badly of our antagonist, whichever one seems to loom at a given moment. It is a convention of modern literature, and of the going-on of talking heads and public intellectuals, to project what are said to be emerging trends into a future in which cultural, intellectual, moral, and economic decline will have hit bottom, more or less.

Somehow this kind of talk always seems brave and deep. The specifics concerning this abysmal future are vague—Britain will cease to be Britain, America will cease to be America, France will cease to be France, and so on, depending on which country happens to be the focus of Spenglerian gloom. The oldest literature of radical pessimism can be read as prophecy. Of course these three societies have changed profoundly in the last hundred years, the last fifty years, and few with any knowledge of history would admit to regretting the change. What is being invoked is the notion of a precious and unnamable essence, second nature to some, in the marrow of their bones, in effect. By this view others, whether they will or no, cannot understand or value it, and therefore they are a threat.

The definitions of “some” and “others” are unclear and shifting. In America, since we are an immigrant country, our “nativists” may be first- or second-generation Americans whose parents or grandparents were themselves considered suspect on these same grounds. It is almost as interesting as it is disheartening to learn that nativist rhetoric can have impact in a country where precious few can claim to be native in any ordinary sense. Our great experiment has yielded some valuable results—here a striking demonstration of the emptiness of such rhetoric, which is nevertheless loudly persistent in certain quarters in America, and which obviously continues to be influential in Britain and Europe.

Nativism is always aligned with an impulse or strategy to shape the culture with which it claims to have this privileged intimacy. It is urgently intent on identifying enemies and confronting them, and it is hostile to the point of loathing toward aspects of the society that are taken to show their influence. In other words, these lovers of country, these patriots, are wildly unhappy with the country they claim to love, and are bent on remaking it to suit their own preferences, which they feel no need to justify or even fully articulate. Neither do they feel any need to answer the objections of those who see their shaping and their disciplining as mutilation. (...)

What are we doing here, we professors of English? Our project is often dismissed as elitist. That word has a new and novel sting in American politics. This is odd, in a period uncharacteristically dominated by political dynasties. Apparently the slur doesn’t stick to those who show no sign of education or sophistication, no matter what their pedigree. Be that as it may. There is a fundamental slovenliness in much public discourse that can graft heterogeneous things together around a single word. There is justified alarm about the bizarre concentrations of wealth that have occurred globally, and the tiny fraction of the wealthiest one percent who have wildly disproportionate influence over the lives of the rest of us. They are called the elite, and so are those of us who encourage the kind of thinking that probably does make certain of the young less than ideal recruits to their armies of the employed.

If there is a point where the two meanings overlap, it would be in the fact that the teaching we do is what in America we have always called liberal education, education appropriate to free people, very much including those old Iowans who left the university to return to the hamlet or the farm. Now, in a country richer than any they could have imagined, we are endlessly told we must cede that humane freedom to a very uncertain promise of employability. It seems most unlikely that any oligarch foresees this choice as being forced on his or her own children. I note here that these criticisms and pressures are not brought to bear on our private universities, though most or all of them receive government money. Elitism in its classic sense is not being attacked but asserted and defended.

If I seem to have conceded an important point in saying that the humanities do not prepare ideal helots, economically speaking, I do not at all mean to imply that they are less than ideal for preparing capable citizens, imaginative and innovative contributors to a full and generous, and largely unmonetizable, national life. America has known long enough how to be a prosperous country, for all its deviations from the narrow path of economic rationalism. Empirically speaking, these errancies are highly compatible with our flourishing economically, if they are not a cause of it, which is more than we can know. The politicians who attack public higher education as too expensive have made it so for electoral or ideological reasons and could undo the harm with the stroke of a pen. They have created the crisis to which they hope to bring their draconian solutions.

by Marilynne Robinson, NYRB | Read more:

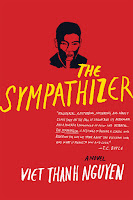

Image: Alexis de Tocqueville; portrait by Théodore Chassériau, 1850