Wednesday, November 8, 2017

Tuesday, November 7, 2017

Let the People Pick the President

The winners of Tuesday’s elections — Republican or Democrat, for governor, mayor or dogcatcher — all have one thing in common: They received more votes than their opponent. That seems like a pretty fair way to run an electoral race, which is why every election in America uses it — except the most important one of all.

Was it just a year ago that more than 136 million Americans cast their ballots for president, choosing Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump by nearly three million votes, only to be thwarted by a 200-year-old constitutional anachronism designed in part to appease slaveholders and ratified when no one but white male landowners could vote?

It feels more like, oh, 17 years — the last time, incidentally, that the American people chose one candidate for president and the Electoral College imposed the other.

In both cases the loser was a Democrat, a fact that has tempted more than a few people to dismiss complaints about the Electoral College as nothing but partisan sour grapes. That’s a mistake. For one thing, Republicans nearly suffered the same fate in 2004. A switch of just 60,000 votes in Ohio would have awarded the White House to John Kerry, who lost the national popular vote by roughly the same margin as Mr. Trump. More important, decades of polling have found that Americans of all stripes would prefer that the president be chosen directly by the people and not by 538 party functionaries six weeks after Election Day.

In both cases the loser was a Democrat, a fact that has tempted more than a few people to dismiss complaints about the Electoral College as nothing but partisan sour grapes. That’s a mistake. For one thing, Republicans nearly suffered the same fate in 2004. A switch of just 60,000 votes in Ohio would have awarded the White House to John Kerry, who lost the national popular vote by roughly the same margin as Mr. Trump. More important, decades of polling have found that Americans of all stripes would prefer that the president be chosen directly by the people and not by 538 party functionaries six weeks after Election Day.

President Trump agrees, or at least he used to. In 2012, when he thought Barack Obama would lose the popular vote but still retake the White House, he called the Electoral College “a disaster for a democracy.” Last November, days after his own victory, Mr. Trump said: “I would rather see it where you went with simple votes. You know, you get 100 million votes, and somebody else gets 90 million votes, and you win. There’s a reason for doing this, because it brings all the states into play.”

He was right, even if he has since converted to an Electoral College advocate. The existing winner-take-all system, which awards all of a state’s electoral votes to the popular-vote winner in that state, no matter how close the race, is deeply anti-democratic. It treats tens of millions of Americans — from Republicans in Boston to Democrats in Biloxi — as if their voices don’t matter.

Defenders of the Electoral College argue that it was created to protect the interests of smaller states, whose voters would otherwise be overwhelmed by the much larger populations living in urban areas along the coasts. That’s wrong as a matter of history: The framers of the Constitution were concerned primarily with ensuring that the president wasn’t selected by uneducated commoners. The electors were meant to be a deliberative body of intelligent, well-informed men who would be immune to corruption. (The arrangement was also a gift to the Southern states, with their large, unenfranchised populations of slaves.)

But regardless of its original intent, the Electoral College today is, as Mr. Trump said, a disaster for a democracy. Modern presidential campaigns ignore almost all states, large and small alike, in favor of a handful that are closely divided between Republicans and Democrats — and even within those states, they focus on a few key regions. In 2016, two-thirds of all public campaign events were held in just six states: Michigan, Ohio, Florida, Pennsylvania, Virginia and North Carolina; toss in six more and you’ve got 94 percent of all campaign events.

This may be smart campaigning, but it’s terrible for the rest of the country, which is rendered effectively invisible, distorting our politics, our policy debates and even the distribution of federal funds. Candidates focus their platforms on the concerns of battleground states, and presidents who want to stay in office make sure to lavish attention, and money, on the same places. The emphasis on a small number of states also increases the risk to our national security, by creating an easy target for hackers who want to influence the outcome of an election. Perhaps most important, voters outside of swing states know their votes are devalued, if not worthless, and they behave accordingly. In 2012, 64 percent of swing-state voters showed up, compared with 57 percent everywhere else, a pattern that persisted in 2016. What better way to get more voters to register and go to the polls than to ensure that everyone’s vote is weighed equally?

The Electoral College has been the subject of more amendment efforts — 595 as of 2004 — than any other part of the Constitution. But amending the Constitution is a heavy lift. A quicker and more realistic fix is the National Popular Vote interstate compact, under which states agree to award all of their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote. The agreement kicks in as soon as states representing a total of 270 electoral votes sign on, ensuring that the popular vote will always pick the president. So far, 10 states and the District of Columbia have joined, representing 165 electoral votes. The problem is that they are all solidly Democratic, which only adds to the suspicion that this is no more than a partisan game. It’s not: When Mr. Trump is not making up stories about millions of illegal voters, he has argued that if the presidency were decided by popular vote, he would have campaigned differently and still would have won. He may well be right.

How can red states be persuaded to sign on and give all their citizens a voice? Some, like Georgia and Arizona, may not stay red for much longer. But even deep-red states would benefit from the infusion of attention and cash from campaigns seeking to rustle up every vote they can find.

This problem isn’t going away; if anything it’s going to get worse as Americans continue to cluster. Half the population now lives in just nine states. It’s time for states that have been on the fence about the national popular-vote compact to get off and sign on. Connecticut, Oregon and Delaware have all come close to passing the compact in recent years; they should get it done now. Yes, they’re three reliably blue states representing 17 electoral votes among them, but every vote counts.

Was it just a year ago that more than 136 million Americans cast their ballots for president, choosing Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump by nearly three million votes, only to be thwarted by a 200-year-old constitutional anachronism designed in part to appease slaveholders and ratified when no one but white male landowners could vote?

It feels more like, oh, 17 years — the last time, incidentally, that the American people chose one candidate for president and the Electoral College imposed the other.

In both cases the loser was a Democrat, a fact that has tempted more than a few people to dismiss complaints about the Electoral College as nothing but partisan sour grapes. That’s a mistake. For one thing, Republicans nearly suffered the same fate in 2004. A switch of just 60,000 votes in Ohio would have awarded the White House to John Kerry, who lost the national popular vote by roughly the same margin as Mr. Trump. More important, decades of polling have found that Americans of all stripes would prefer that the president be chosen directly by the people and not by 538 party functionaries six weeks after Election Day.

In both cases the loser was a Democrat, a fact that has tempted more than a few people to dismiss complaints about the Electoral College as nothing but partisan sour grapes. That’s a mistake. For one thing, Republicans nearly suffered the same fate in 2004. A switch of just 60,000 votes in Ohio would have awarded the White House to John Kerry, who lost the national popular vote by roughly the same margin as Mr. Trump. More important, decades of polling have found that Americans of all stripes would prefer that the president be chosen directly by the people and not by 538 party functionaries six weeks after Election Day.President Trump agrees, or at least he used to. In 2012, when he thought Barack Obama would lose the popular vote but still retake the White House, he called the Electoral College “a disaster for a democracy.” Last November, days after his own victory, Mr. Trump said: “I would rather see it where you went with simple votes. You know, you get 100 million votes, and somebody else gets 90 million votes, and you win. There’s a reason for doing this, because it brings all the states into play.”

He was right, even if he has since converted to an Electoral College advocate. The existing winner-take-all system, which awards all of a state’s electoral votes to the popular-vote winner in that state, no matter how close the race, is deeply anti-democratic. It treats tens of millions of Americans — from Republicans in Boston to Democrats in Biloxi — as if their voices don’t matter.

Defenders of the Electoral College argue that it was created to protect the interests of smaller states, whose voters would otherwise be overwhelmed by the much larger populations living in urban areas along the coasts. That’s wrong as a matter of history: The framers of the Constitution were concerned primarily with ensuring that the president wasn’t selected by uneducated commoners. The electors were meant to be a deliberative body of intelligent, well-informed men who would be immune to corruption. (The arrangement was also a gift to the Southern states, with their large, unenfranchised populations of slaves.)

But regardless of its original intent, the Electoral College today is, as Mr. Trump said, a disaster for a democracy. Modern presidential campaigns ignore almost all states, large and small alike, in favor of a handful that are closely divided between Republicans and Democrats — and even within those states, they focus on a few key regions. In 2016, two-thirds of all public campaign events were held in just six states: Michigan, Ohio, Florida, Pennsylvania, Virginia and North Carolina; toss in six more and you’ve got 94 percent of all campaign events.

This may be smart campaigning, but it’s terrible for the rest of the country, which is rendered effectively invisible, distorting our politics, our policy debates and even the distribution of federal funds. Candidates focus their platforms on the concerns of battleground states, and presidents who want to stay in office make sure to lavish attention, and money, on the same places. The emphasis on a small number of states also increases the risk to our national security, by creating an easy target for hackers who want to influence the outcome of an election. Perhaps most important, voters outside of swing states know their votes are devalued, if not worthless, and they behave accordingly. In 2012, 64 percent of swing-state voters showed up, compared with 57 percent everywhere else, a pattern that persisted in 2016. What better way to get more voters to register and go to the polls than to ensure that everyone’s vote is weighed equally?

The Electoral College has been the subject of more amendment efforts — 595 as of 2004 — than any other part of the Constitution. But amending the Constitution is a heavy lift. A quicker and more realistic fix is the National Popular Vote interstate compact, under which states agree to award all of their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote. The agreement kicks in as soon as states representing a total of 270 electoral votes sign on, ensuring that the popular vote will always pick the president. So far, 10 states and the District of Columbia have joined, representing 165 electoral votes. The problem is that they are all solidly Democratic, which only adds to the suspicion that this is no more than a partisan game. It’s not: When Mr. Trump is not making up stories about millions of illegal voters, he has argued that if the presidency were decided by popular vote, he would have campaigned differently and still would have won. He may well be right.

How can red states be persuaded to sign on and give all their citizens a voice? Some, like Georgia and Arizona, may not stay red for much longer. But even deep-red states would benefit from the infusion of attention and cash from campaigns seeking to rustle up every vote they can find.

This problem isn’t going away; if anything it’s going to get worse as Americans continue to cluster. Half the population now lives in just nine states. It’s time for states that have been on the fence about the national popular-vote compact to get off and sign on. Connecticut, Oregon and Delaware have all come close to passing the compact in recent years; they should get it done now. Yes, they’re three reliably blue states representing 17 electoral votes among them, but every vote counts.

by Editorial Board, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Kiersten EssenpreisNever Let Me Go and the Human Condition

I teach college English, which means that I spend a lot of time telling people not to write papers about “the human condition.” The human condition, I tell my students, is vague. What about the human condition are you interested in? I ask. Bodies? Money? Desire? Work? Power? These are things that we could make arguments about. The human condition is not. I give my students a handout of writing tips, a series of “dos and don’ts” I’ve honed over the course of a decade in college classrooms. Many of the “don’ts” regard specificity. Don’t write about society. Be more specific. Don’t tell me about gender norms. Be more specific. Don’t write about the human condition. Be more specific.

I hold to these rules tightly; I think they are good rules, and they certainly lead to more exacting student writing. But when I read that Kazuo Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize for literature last week, my first thought was: Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize because he writes about the human condition.

I hold to these rules tightly; I think they are good rules, and they certainly lead to more exacting student writing. But when I read that Kazuo Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize for literature last week, my first thought was: Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize because he writes about the human condition.

When I teach his 2005 novel Never Let Me Go, I have to break some rules.

For the uninitiated, Never Let Me Go is a novel about a group of young people who are also clones. These clones will grow up and begin to donate their organs in their late teens and twenties and then they will die slow, orchestrated deaths; their bodies will be used to save the lives of others. The clones have been created by a vast government program and there is no escape from it. Never Let Me Go is not a story of rebellion.

The novel is narrated by Kath, who is a carer, which means quite literally that she cares emotionally for other clones going through the donation process. In the first paragraph of the novel, Kath tells us that she’s about to wrap up her work as a carer, that she soon will become a donor. When the novel begins, we don’t quite know what this means. We find out everything very slowly. I have stated the premise of the book more clearly and explicitly than Ishiguro ever does.

Kath is what some people might call an unreliable narrator, but I prefer to think of her as clueless instead. Like the butler of Ishiguro’s earlier novel Remains of the Day, Kath never quite comprehends what’s going on around her, or what’s happening to her. In the parlance of the book, she’s been “told and not told” about her fate. Ishiguro reveals information slowly; the word “clone” doesn’t appear until more than halfway through the novel, and Kath speaks in the euphemisms of the donation program. To die, for example, is to “complete.”

Never Let Me Go is fantastic for developing students’ close reading skills; I start off teaching the novel by close reading its first paragraph with my class for a long time, longer than should be possible. The book is a teacher’s dream: there is almost too much to talk about. We discuss narration and epistemology (how do we know what we know in this book?), genre (is the book science fiction? A crime novel? A bildungsroman?) We can talk Foucault and surveillance, biopolitics, medical ethics, aesthetics, education, gender, sex: this book has everything, which is why I can—and do—fit it onto so many syllabi.

But I also teach this book because it gets under my students’ skin. They tell me this after class, in evaluations, in emails years later, but I can also see it in their faces in my classroom. Never Let Me Go gets to them because it gets them. The narrator is young and confused and sad: so are a lot of college students. Sure, the book is about a massive government program that raises children for slaughter, but so much of the book, a good 80% of it, I’d venture, is about daily childhood and teenage life: alliances between friends, art projects, soccer games, awkward sex ed classes, writing essays, falling in love. There are hazy and obscure threats from the adult world, which the clones feel but don’t quite understand. The clones feel powerless, they know that death is coming—kind of—and yet they live their lives anyway.

In this, the clones are just like us.

Whenever I teach Never Let Me Go, there’s a moment, almost always on the final day of class on the novel, when my students get demonstrably frustrated with Kath and the other clones. They ask: where is their anger? Why don’t they rebel? Why do they passively accept their deaths? Why don’t they do something? (The most the clones try, and fail to do is temporarily defer—not circumvent—their donations.) I, summoning something in myself that I don’t usually summon, pause and then intone: why don’t you rebel? Where is your anger? Why do you passively accept your deaths?

I have taught this book many times, and I know how to orchestrate this moment. I lean forward in my chair. You guys know you’re going to die, too, right? Why don’t you do something?

Sometimes my students are silent, but sometimes they start arguing with me about details that I frankly don’t care about in this particular moment. The clones will die sooner than we will (will they? What do you know that I don’t?) We’re not oppressed by governments restricting what we do with other bodies (It’s never a woman who says this.) We can go round and round, and I will always have an answer.

You are going to die and there’s nothing you can do about it, I tell them. It’s the human condition.

by Jacquelyn Ardam, Avidly | Read more:

Image: Goodreads

I hold to these rules tightly; I think they are good rules, and they certainly lead to more exacting student writing. But when I read that Kazuo Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize for literature last week, my first thought was: Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize because he writes about the human condition.

I hold to these rules tightly; I think they are good rules, and they certainly lead to more exacting student writing. But when I read that Kazuo Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize for literature last week, my first thought was: Ishiguro won the Nobel Prize because he writes about the human condition.When I teach his 2005 novel Never Let Me Go, I have to break some rules.

For the uninitiated, Never Let Me Go is a novel about a group of young people who are also clones. These clones will grow up and begin to donate their organs in their late teens and twenties and then they will die slow, orchestrated deaths; their bodies will be used to save the lives of others. The clones have been created by a vast government program and there is no escape from it. Never Let Me Go is not a story of rebellion.

The novel is narrated by Kath, who is a carer, which means quite literally that she cares emotionally for other clones going through the donation process. In the first paragraph of the novel, Kath tells us that she’s about to wrap up her work as a carer, that she soon will become a donor. When the novel begins, we don’t quite know what this means. We find out everything very slowly. I have stated the premise of the book more clearly and explicitly than Ishiguro ever does.

Kath is what some people might call an unreliable narrator, but I prefer to think of her as clueless instead. Like the butler of Ishiguro’s earlier novel Remains of the Day, Kath never quite comprehends what’s going on around her, or what’s happening to her. In the parlance of the book, she’s been “told and not told” about her fate. Ishiguro reveals information slowly; the word “clone” doesn’t appear until more than halfway through the novel, and Kath speaks in the euphemisms of the donation program. To die, for example, is to “complete.”

Never Let Me Go is fantastic for developing students’ close reading skills; I start off teaching the novel by close reading its first paragraph with my class for a long time, longer than should be possible. The book is a teacher’s dream: there is almost too much to talk about. We discuss narration and epistemology (how do we know what we know in this book?), genre (is the book science fiction? A crime novel? A bildungsroman?) We can talk Foucault and surveillance, biopolitics, medical ethics, aesthetics, education, gender, sex: this book has everything, which is why I can—and do—fit it onto so many syllabi.

But I also teach this book because it gets under my students’ skin. They tell me this after class, in evaluations, in emails years later, but I can also see it in their faces in my classroom. Never Let Me Go gets to them because it gets them. The narrator is young and confused and sad: so are a lot of college students. Sure, the book is about a massive government program that raises children for slaughter, but so much of the book, a good 80% of it, I’d venture, is about daily childhood and teenage life: alliances between friends, art projects, soccer games, awkward sex ed classes, writing essays, falling in love. There are hazy and obscure threats from the adult world, which the clones feel but don’t quite understand. The clones feel powerless, they know that death is coming—kind of—and yet they live their lives anyway.

In this, the clones are just like us.

Whenever I teach Never Let Me Go, there’s a moment, almost always on the final day of class on the novel, when my students get demonstrably frustrated with Kath and the other clones. They ask: where is their anger? Why don’t they rebel? Why do they passively accept their deaths? Why don’t they do something? (The most the clones try, and fail to do is temporarily defer—not circumvent—their donations.) I, summoning something in myself that I don’t usually summon, pause and then intone: why don’t you rebel? Where is your anger? Why do you passively accept your deaths?

I have taught this book many times, and I know how to orchestrate this moment. I lean forward in my chair. You guys know you’re going to die, too, right? Why don’t you do something?

Sometimes my students are silent, but sometimes they start arguing with me about details that I frankly don’t care about in this particular moment. The clones will die sooner than we will (will they? What do you know that I don’t?) We’re not oppressed by governments restricting what we do with other bodies (It’s never a woman who says this.) We can go round and round, and I will always have an answer.

You are going to die and there’s nothing you can do about it, I tell them. It’s the human condition.

by Jacquelyn Ardam, Avidly | Read more:

Image: Goodreads

The Truth About the US ‘Opioid Crisis’ – Prescriptions Aren’t the Problem

The news media is awash with hysteria about the opioid crisis (or opioid epidemic). But what exactly are we talking about? If you Google “opioid crisis”, nine times out of 10 the first paragraph of whatever you’re reading will report on death rates. That’s right, the overdose crisis.

For example, the lead article on the “opioid crisis” on the US National Institutes of Health website begins with this sentence: “Every day, more than 90 Americans die after overdosing on opioids.”

Is the opioid crisis the same as the overdose crisis? No. One has to do with addiction rates, the other with death rates. And addiction rates aren’t rising much, if at all, except perhaps among middle-class whites.

Is the opioid crisis the same as the overdose crisis? No. One has to do with addiction rates, the other with death rates. And addiction rates aren’t rising much, if at all, except perhaps among middle-class whites.

Let’s look a bit deeper.

The overdose crisis is unmistakable. I reported on some of the statistics and causes in the Guardian last July. I think the most striking fact is that drug overdose is the leading cause of death for Americans under 50. Some people swallow, or (more often) inject, more opioids than their body can handle, which causes the breathing reflex to shut down. But drug overdoses that include opioids (about 63%) are most often caused by a combination of drugs (or drugs and alcohol) and most often include illegal drugs (eg heroin). When prescription drugs are involved, methadone and oxycontin are at the top of the list, and these drugs are notoriously acquired and used illicitly.

Yet the most bellicose response to the overdose crisis is that we must stop doctors from prescribing opioids. Hmmm. (...)

First, why not clarify that most of the abuse of prescription pain pills is not by those for whom they’re prescribed? Among those for whom they are prescribed, the onset of addiction (which is usually temporary) is about 10% for those with a previous drug-use history, and less than 1% for those with no such history. Note also the oft-repeated maxim that most heroin users start off on prescription opioids. Most divers start off as swimmers, but most swimmers don’t become divers.

Second, wouldn’t it be sensible for the media to distinguish street drugs such as heroin from pain pills? We’re talking about radically different groups of users.

Third, virtually all experts agree that fentanyl and related drugs are driving the overdose epidemic. These are many times stronger than heroin and far cheaper, so drug dealers often use them to lace or replace heroin. Yet, because fentanyl is a manufactured pharmaceutical prescribed for severe pain, the media often describe it as a prescription painkiller – however it reaches its users.

It’s remarkably irresponsible to ignore these distinctions and then use “sum total” statistics to scare doctors, policymakers and review boards into severely limiting the prescription of pain pills.

By the way, if you were either addicted to opioids or needed them badly for pain relief, what would you do if your prescription was abruptly terminated? Heroin is now easier to acquire than ever, partly because it’s available on the darknet and partly because present-day distribution networks function like independent cells rather than monolithic gangs – much harder to bust. And, of course, increased demand leads to increased supply. Addiction and pain are both serious problems, serious sources of suffering. If you were afflicted with either and couldn’t get help from your doctor, you’d try your best to get relief elsewhere. And your odds of overdosing would increase astronomically.

It’s doctors – not politicians, journalists, or professional review bodies – who are best equipped and motivated to decide what their patients need, at what doses, for what periods of time. And the vast majority of doctors are conscientious, responsible and ethical.

Addiction is not caused by drug availability. The abundant availability of alcohol doesn’t turn us all into alcoholics. No, addiction is caused by psychological (and economic) suffering, especially in childhood and adolescence (eg abuse, neglect, and other traumatic experiences), as revealed by massive correlations between adverse childhood experiences and later substance use. The US is at or near the bottom of the developed world in its record on child welfare and child poverty. No wonder there’s an addiction problem. And how easy it is to blame doctors for causing it.

[ed. I'd agree, and also stress the difference between dependence and addiction. Many people are dependent on various medications and other things for a variety of physical and mental ailments, yet they continue to function productively without ever becoming addicted (xanax, adderall, ssri's, caffeine, marijuana, etc.). Personal physicians are probably the best hope we have to respond to individual patient needs, especially now that the risks of opioids are so well documented and a more rigorous prescription tracking system is in place. Most importantly, we need to get people off the streets and away from uncontrolled products. More prescribing and dispensing restrictions will only make the problem worse.]

For example, the lead article on the “opioid crisis” on the US National Institutes of Health website begins with this sentence: “Every day, more than 90 Americans die after overdosing on opioids.”

Is the opioid crisis the same as the overdose crisis? No. One has to do with addiction rates, the other with death rates. And addiction rates aren’t rising much, if at all, except perhaps among middle-class whites.

Is the opioid crisis the same as the overdose crisis? No. One has to do with addiction rates, the other with death rates. And addiction rates aren’t rising much, if at all, except perhaps among middle-class whites.Let’s look a bit deeper.

The overdose crisis is unmistakable. I reported on some of the statistics and causes in the Guardian last July. I think the most striking fact is that drug overdose is the leading cause of death for Americans under 50. Some people swallow, or (more often) inject, more opioids than their body can handle, which causes the breathing reflex to shut down. But drug overdoses that include opioids (about 63%) are most often caused by a combination of drugs (or drugs and alcohol) and most often include illegal drugs (eg heroin). When prescription drugs are involved, methadone and oxycontin are at the top of the list, and these drugs are notoriously acquired and used illicitly.

Yet the most bellicose response to the overdose crisis is that we must stop doctors from prescribing opioids. Hmmm. (...)

First, why not clarify that most of the abuse of prescription pain pills is not by those for whom they’re prescribed? Among those for whom they are prescribed, the onset of addiction (which is usually temporary) is about 10% for those with a previous drug-use history, and less than 1% for those with no such history. Note also the oft-repeated maxim that most heroin users start off on prescription opioids. Most divers start off as swimmers, but most swimmers don’t become divers.

Second, wouldn’t it be sensible for the media to distinguish street drugs such as heroin from pain pills? We’re talking about radically different groups of users.

Third, virtually all experts agree that fentanyl and related drugs are driving the overdose epidemic. These are many times stronger than heroin and far cheaper, so drug dealers often use them to lace or replace heroin. Yet, because fentanyl is a manufactured pharmaceutical prescribed for severe pain, the media often describe it as a prescription painkiller – however it reaches its users.

It’s remarkably irresponsible to ignore these distinctions and then use “sum total” statistics to scare doctors, policymakers and review boards into severely limiting the prescription of pain pills.

By the way, if you were either addicted to opioids or needed them badly for pain relief, what would you do if your prescription was abruptly terminated? Heroin is now easier to acquire than ever, partly because it’s available on the darknet and partly because present-day distribution networks function like independent cells rather than monolithic gangs – much harder to bust. And, of course, increased demand leads to increased supply. Addiction and pain are both serious problems, serious sources of suffering. If you were afflicted with either and couldn’t get help from your doctor, you’d try your best to get relief elsewhere. And your odds of overdosing would increase astronomically.

It’s doctors – not politicians, journalists, or professional review bodies – who are best equipped and motivated to decide what their patients need, at what doses, for what periods of time. And the vast majority of doctors are conscientious, responsible and ethical.

Addiction is not caused by drug availability. The abundant availability of alcohol doesn’t turn us all into alcoholics. No, addiction is caused by psychological (and economic) suffering, especially in childhood and adolescence (eg abuse, neglect, and other traumatic experiences), as revealed by massive correlations between adverse childhood experiences and later substance use. The US is at or near the bottom of the developed world in its record on child welfare and child poverty. No wonder there’s an addiction problem. And how easy it is to blame doctors for causing it.

by Marc Lewis, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: John Moore/Getty Images[ed. I'd agree, and also stress the difference between dependence and addiction. Many people are dependent on various medications and other things for a variety of physical and mental ailments, yet they continue to function productively without ever becoming addicted (xanax, adderall, ssri's, caffeine, marijuana, etc.). Personal physicians are probably the best hope we have to respond to individual patient needs, especially now that the risks of opioids are so well documented and a more rigorous prescription tracking system is in place. Most importantly, we need to get people off the streets and away from uncontrolled products. More prescribing and dispensing restrictions will only make the problem worse.]

Monday, November 6, 2017

Tiny Human Brain Organoids Implanted Into Rodents, Triggering Ethical Concerns

Minuscule blobs of human brain tissue have come a long way in the four years since scientists in Vienna discovered how to create them from stem cells.

The most advanced of these human brain organoids — no bigger than a lentil and, until now, existing only in test tubes — pulse with the kind of electrical activity that animates actual brains. They give birth to new neurons, much like full-blown brains. And they develop the six layers of the human cortex, the region responsible for thought, speech, judgment, and other advanced cognitive functions.

These micro quasi-brains are revolutionizing research on human brain development and diseases from Alzheimer’s to Zika, but the headlong rush to grow the most realistic, most highly developed brain organoids has thrown researchers into uncharted ethical waters. Like virtually all experts in the field, neuroscientist Hongjun Song of the University of Pennsylvania doesn’t “believe an organoid in a dish can think,” he said, “but it’s an issue we need to discuss.”

These micro quasi-brains are revolutionizing research on human brain development and diseases from Alzheimer’s to Zika, but the headlong rush to grow the most realistic, most highly developed brain organoids has thrown researchers into uncharted ethical waters. Like virtually all experts in the field, neuroscientist Hongjun Song of the University of Pennsylvania doesn’t “believe an organoid in a dish can think,” he said, “but it’s an issue we need to discuss.”

Those discussions will become more urgent after this weekend. At a neuroscience meeting, two teams of researchers will report implanting human brain organoids into the brains of lab rats and mice, raising the prospect that the organized, functional human tissue could develop further within a rodent. Separately, another lab has confirmed to STAT that it has connected human brain organoids to blood vessels, the first step toward giving them a blood supply.

That is necessary if the organoids are to grow bigger, probably the only way they can mimic fully grown brains and show how disorders such as autism, epilepsy, and schizophrenia unfold. But “vascularization” of cerebral organoids also raises such troubling ethical concerns that, previously, the lab paused its efforts to even try it.

“We are entering totally new ground here,” said Christof Koch, president of the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle. “The science is advancing so rapidly, the ethics can’t keep up.”

by Sharon Begley, STAT | Read more:

The most advanced of these human brain organoids — no bigger than a lentil and, until now, existing only in test tubes — pulse with the kind of electrical activity that animates actual brains. They give birth to new neurons, much like full-blown brains. And they develop the six layers of the human cortex, the region responsible for thought, speech, judgment, and other advanced cognitive functions.

These micro quasi-brains are revolutionizing research on human brain development and diseases from Alzheimer’s to Zika, but the headlong rush to grow the most realistic, most highly developed brain organoids has thrown researchers into uncharted ethical waters. Like virtually all experts in the field, neuroscientist Hongjun Song of the University of Pennsylvania doesn’t “believe an organoid in a dish can think,” he said, “but it’s an issue we need to discuss.”

These micro quasi-brains are revolutionizing research on human brain development and diseases from Alzheimer’s to Zika, but the headlong rush to grow the most realistic, most highly developed brain organoids has thrown researchers into uncharted ethical waters. Like virtually all experts in the field, neuroscientist Hongjun Song of the University of Pennsylvania doesn’t “believe an organoid in a dish can think,” he said, “but it’s an issue we need to discuss.”Those discussions will become more urgent after this weekend. At a neuroscience meeting, two teams of researchers will report implanting human brain organoids into the brains of lab rats and mice, raising the prospect that the organized, functional human tissue could develop further within a rodent. Separately, another lab has confirmed to STAT that it has connected human brain organoids to blood vessels, the first step toward giving them a blood supply.

That is necessary if the organoids are to grow bigger, probably the only way they can mimic fully grown brains and show how disorders such as autism, epilepsy, and schizophrenia unfold. But “vascularization” of cerebral organoids also raises such troubling ethical concerns that, previously, the lab paused its efforts to even try it.

“We are entering totally new ground here,” said Christof Koch, president of the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle. “The science is advancing so rapidly, the ethics can’t keep up.”

by Sharon Begley, STAT | Read more:

Image:Xuyu Qian/Johns Hopkins University

[ed. If a thing can be achieved it will be... commonly known as Pandora's Box. There's bit of dark irony too, putting human brain tissue in lab rats. As Lily Tomlin once said "the trouble with the rat race is, even if you win you're still a rat".]

Leaked Documents Expose Secret Tale Of Apple’s Offshore Island Hop

It was May 2013, and Apple Inc. chief executive Tim Cook was angry.

He sat before the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, which had completed an inquiry into how Apple avoided tens of billions of dollars in taxes by shifting profits into Irish subsidiaries that the subcommittee’s chairman called “ghost companies.”

“We pay all the taxes we owe, every single dollar,” Cook declared. “We do not depend on tax gimmicks. . . . We do not stash money on some Caribbean island.”

Five months later, Ireland bowed to international pressure and announced a crackdown on Irish firms, like Apple’s subsidiaries, that claimed that almost all of their income was not subject to taxes in Ireland or anywhere else in the world.

Now leaked documents, called the Paradise Papers, shine a light on how the iPhone maker responded to this move. Despite its CEO’s public rejection of island havens, that’s where Apple turned as it began shopping for a new tax refuge.

Apple’s advisers at one of the world’s top law firms, U.S.-headquartered Baker McKenzie, canvassed one of the leading players in the offshore world, a firm of lawyers called Appleby, which specialized in setting up and administering tax haven companies.

A questionnaire that Baker McKenzie emailed in March 2014 set out 14 questions for Appleby’s offices in the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, the Isle of Man, Guernsey and Jersey.

One asked that the offices: “Confirm that an Irish company can conduct management activities . . . without being subject to taxation in your jurisdiction.”

Apple also asked for assurances that the local political climate would remain friendly: “Are there any developments suggesting that the law may change in an unfavourable way in the foreseeable future?”

In the end, Apple settled on Jersey, a tiny island in the English Channel that, like many Caribbean havens, charges no tax on corporate profits for most companies. Jersey was to play a significant role in Apple’s newly configured Irish tax structure set up in late 2014. Under this arrangement, the MacBook-maker has continued to enjoy ultra-low tax rates on most of its profits and now holds much of its non-U.S. earnings in a $252 billion mountain of cash offshore. The Irish government’s crackdown on shadow companies, meanwhile, has had little effect.

The inside story of Apple’s hunt for a new avoidance strategy is among the disclosures emerging from a leak of secret corporate records that reveals how the offshore tax game is played by Apple, Nike, Uber and other multinational corporations – and how top law firms help them exploit gaps between differing tax codes around the world.

The documents come from the internal files of offshore law firm Appleby and corporate services provider Estera, two businesses that operated together under the Appleby name until Estera became independent in 2016.

The files show how Appleby played a cameo role in creating many cross-border tax structures. German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung obtained the records and shared them with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and its media partners, including The New York Times, Australia’s ABC, the BBC in the United Kingdom, Le Monde in France and CBC in Canada.

These disclosures come as the White House and Congress consider cutting the U.S. federal tax on corporate income, pushing its top rate of 35 percent down to 20 percent or lower. President Donald Trump has insisted that American firms are getting a bad deal from current tax rules.

The documents show that, in reality, many big U.S. multinationals pay income taxes at very low rates, thanks in part to complex corporate structures they set up with the help of a global network of elite tax advisers.

In this regard, Apple has led the field. Despite almost all design and development of its products taking place in the U.S., the iPhone-maker has for years been able to report that about two-thirds of its worldwide profits were made in other countries, where it has used loopholes to access ultra-low foreign tax rates.

Now leaked documents help show how Apple quietly carried out a restructuring of its Irish companies at the end of 2014, allowing it to carry on paying taxes at low rates on the majority of global profits.

Multinationals that transfer intangible assets to tax havens and adopt other aggressive avoidance strategies are costing governments around the world as much as $240 billion a year in lost tax revenue, according to a conservative estimate in 2015 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

He sat before the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, which had completed an inquiry into how Apple avoided tens of billions of dollars in taxes by shifting profits into Irish subsidiaries that the subcommittee’s chairman called “ghost companies.”

“We pay all the taxes we owe, every single dollar,” Cook declared. “We do not depend on tax gimmicks. . . . We do not stash money on some Caribbean island.”

Five months later, Ireland bowed to international pressure and announced a crackdown on Irish firms, like Apple’s subsidiaries, that claimed that almost all of their income was not subject to taxes in Ireland or anywhere else in the world.

Now leaked documents, called the Paradise Papers, shine a light on how the iPhone maker responded to this move. Despite its CEO’s public rejection of island havens, that’s where Apple turned as it began shopping for a new tax refuge.

Apple’s advisers at one of the world’s top law firms, U.S.-headquartered Baker McKenzie, canvassed one of the leading players in the offshore world, a firm of lawyers called Appleby, which specialized in setting up and administering tax haven companies.

A questionnaire that Baker McKenzie emailed in March 2014 set out 14 questions for Appleby’s offices in the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda, the Isle of Man, Guernsey and Jersey.

One asked that the offices: “Confirm that an Irish company can conduct management activities . . . without being subject to taxation in your jurisdiction.”

Apple also asked for assurances that the local political climate would remain friendly: “Are there any developments suggesting that the law may change in an unfavourable way in the foreseeable future?”

In the end, Apple settled on Jersey, a tiny island in the English Channel that, like many Caribbean havens, charges no tax on corporate profits for most companies. Jersey was to play a significant role in Apple’s newly configured Irish tax structure set up in late 2014. Under this arrangement, the MacBook-maker has continued to enjoy ultra-low tax rates on most of its profits and now holds much of its non-U.S. earnings in a $252 billion mountain of cash offshore. The Irish government’s crackdown on shadow companies, meanwhile, has had little effect.

The inside story of Apple’s hunt for a new avoidance strategy is among the disclosures emerging from a leak of secret corporate records that reveals how the offshore tax game is played by Apple, Nike, Uber and other multinational corporations – and how top law firms help them exploit gaps between differing tax codes around the world.

The documents come from the internal files of offshore law firm Appleby and corporate services provider Estera, two businesses that operated together under the Appleby name until Estera became independent in 2016.

The files show how Appleby played a cameo role in creating many cross-border tax structures. German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung obtained the records and shared them with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and its media partners, including The New York Times, Australia’s ABC, the BBC in the United Kingdom, Le Monde in France and CBC in Canada.

These disclosures come as the White House and Congress consider cutting the U.S. federal tax on corporate income, pushing its top rate of 35 percent down to 20 percent or lower. President Donald Trump has insisted that American firms are getting a bad deal from current tax rules.

The documents show that, in reality, many big U.S. multinationals pay income taxes at very low rates, thanks in part to complex corporate structures they set up with the help of a global network of elite tax advisers.

In this regard, Apple has led the field. Despite almost all design and development of its products taking place in the U.S., the iPhone-maker has for years been able to report that about two-thirds of its worldwide profits were made in other countries, where it has used loopholes to access ultra-low foreign tax rates.

Now leaked documents help show how Apple quietly carried out a restructuring of its Irish companies at the end of 2014, allowing it to carry on paying taxes at low rates on the majority of global profits.

Multinationals that transfer intangible assets to tax havens and adopt other aggressive avoidance strategies are costing governments around the world as much as $240 billion a year in lost tax revenue, according to a conservative estimate in 2015 by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

by Simon Bowers, ICIJ | Read more:

Image: SEC

[ed. The question now is will the Paradise Papers even register with the American public? (Rhetorical, I know). Of course they won't. Our government/media/corporations/elite (GMCE? Hell, let's just call them the Matrix) won't let them. They'll be spun out, delegitimized, obfuscated... and, well you know the drill. America's two-minute attention span will move on. And like a ripple on a pond, or an errant blip on a flatlined brain monitor, the matter will quickly be forgotten. I haven't looked at the latest Republican tax plan but I can guess what's in it (more tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy!). And, of course, a big bonus for 'repatriating' American corporation profits that should never have been allowed to be sequestered in the first place. (I love that term 'repatriating', like our money's been on vacation for years, which I guess it has). See also: Cohn Says Repatriation Tax Rate Will Be in the ‘10% Range. Update. The process begins: Was it wrong to hack and leak the Panama Papers? and What the Paradise Papers Tell Us About Global Business and Political Elites]

Labels:

Business,

Crime,

Economics,

Government,

Politics

Pat Metheny

[ed. Genius. How could someone even conceptualize a composition like this? Here's another one. See also: Just Jazz Guitar Interview - Pat Metheny]

A Restaurant Ruined My Life

Seven years ago, I was an analyst for Telefilm Canada, earning a paycheque by sitting in a grey cube and shuffling box office stats. At the end of each day, I would rush home to my wife, two daughters and truest passion: making dinner. The sights and smells of my kitchen were balms to my soul.

Cooking would have remained a hobby if I hadn’t stumbled across old footage of Michelin chef Marco Pierre White preparing a stuffed pig’s trotter on YouTube. It was an audacious dish and maybe even a bit sinister. It looked a little like a stubby, sun-baked human hand on a platter. I loved how the deft skill of an unlikely genius and a few choice ingredients transformed a cheap cut of meat into a beautiful plate. The dish was transcendent to me, and in a rough kind of way, so was its creator. White smoked. White sneered. White swore. He was handsome. I could envision him swaggering around his Hampshire restaurant, the Yew Tree Inn, dropping exquisite plates of food in front of wealthy customers with all the bombast of a star footballer. As he got older and no longer cooked in the kitchen, he was known to hang about the bar and drink cider with customers, at times with a .22 rifle close by in case he had the sudden urge to go rabbit hunting. To me, Marco Pierre White was inspirational. I wanted to be him. And I wanted my own Yew Tree.

Cooking would have remained a hobby if I hadn’t stumbled across old footage of Michelin chef Marco Pierre White preparing a stuffed pig’s trotter on YouTube. It was an audacious dish and maybe even a bit sinister. It looked a little like a stubby, sun-baked human hand on a platter. I loved how the deft skill of an unlikely genius and a few choice ingredients transformed a cheap cut of meat into a beautiful plate. The dish was transcendent to me, and in a rough kind of way, so was its creator. White smoked. White sneered. White swore. He was handsome. I could envision him swaggering around his Hampshire restaurant, the Yew Tree Inn, dropping exquisite plates of food in front of wealthy customers with all the bombast of a star footballer. As he got older and no longer cooked in the kitchen, he was known to hang about the bar and drink cider with customers, at times with a .22 rifle close by in case he had the sudden urge to go rabbit hunting. To me, Marco Pierre White was inspirational. I wanted to be him. And I wanted my own Yew Tree.

I soon joined the burgeoning ranks of the know-it-all gourmand. I owned fancy knives. I photographed my food. I had a subscription to Lucky Peach. I had a well-thumbed copy of Kitchen Confidential and a demi-glace-spattered copy of The French Laundry Cookbook. At work, I had trouble concentrating on spreadsheets and instead found myself scribbling menus on graph paper. I could picture a quaint dining room with wooden tables, scalloped plates and plaid napkins. I even came up with the perfect name: the Beech Tree, inspired by the Yew Tree. I naïvely figured I could do it as well as the restaurant lifers, the tattooed dude-chefs and the nut-busting empire builders. What I lacked in experience I could make up for in enthusiasm.

In 2011, I applied to operate a booth at the Toronto Underground Food Market, a short-lived festival, known as TUM, where home cooks could sell their culinary creations to the public. I served mini-panko-crusted codfish cakes with green pea pesto, gourmet pork belly sandwiches, and wild mushroom and black pudding hash. I slogged through each step of thrice-cooked English chips, my fingers cramping so severely from peeling 100 pounds of potatoes that I almost called 911. In the end, I fed 400 people, and they liked my food. Several local bloggers wrote about my dishes. It was an adrenalin rush like no other. I lost money, but I didn’t care. My dream was gnawing at my insides.

Eighty per cent of first-time restaurateurs fail. I knew this. Opening a restaurant was the least sensible, dumbest thing I could do. My wife, Dorothy, a daycare worker, was coasting toward the end of a maternity leave, and we had two kids to feed. I was in no position to take a risk. But if it succeeded, I could make more money than any office job had ever paid me. We could enjoy a better lifestyle and maybe buy a nicer house. Plus, I’d be doing what I loved.

I pitched the concept to Dorothy, explaining that I would be front of house, designing the menu, signing cheques and glad-handing customers. I told her about a guy I had met at TUM who had launched a successful restaurant and still made it home in time to tuck in the kids every night. I proposed that she work alongside me, hosting the lunch service while our girls were at school, and I would look after the dinner service. We could run errands in the mornings, maybe sneak away for breakfast at the competition and write it off as research. Eventually, she embraced my dream, too. Now I just needed to find the money.

Six months later, an opportunity arose. My position at Telefilm, a Crown corporation, was eliminated. I was offered a lateral step, but if I walked away, I would be able to cash out $60,000 from my $130,000 pension. I could already see the tufted banquettes, the Victorian wallpaper, the brass beer taps—and me, a rifle slung over my shoulder, a pint of cider in hand. As my last day approached, I brought up my idea over drinks with a friend named Jameson, who owned a popular west-end bar. After some talk about which craft beers I should offer, he turned serious. “Are you sure you want to do this?” he asked. “I don’t think you know what you’re getting yourself into.” I smiled, drained my pint glass. “You pulled it off,” I said. “Why can’t I?”

Cooking would have remained a hobby if I hadn’t stumbled across old footage of Michelin chef Marco Pierre White preparing a stuffed pig’s trotter on YouTube. It was an audacious dish and maybe even a bit sinister. It looked a little like a stubby, sun-baked human hand on a platter. I loved how the deft skill of an unlikely genius and a few choice ingredients transformed a cheap cut of meat into a beautiful plate. The dish was transcendent to me, and in a rough kind of way, so was its creator. White smoked. White sneered. White swore. He was handsome. I could envision him swaggering around his Hampshire restaurant, the Yew Tree Inn, dropping exquisite plates of food in front of wealthy customers with all the bombast of a star footballer. As he got older and no longer cooked in the kitchen, he was known to hang about the bar and drink cider with customers, at times with a .22 rifle close by in case he had the sudden urge to go rabbit hunting. To me, Marco Pierre White was inspirational. I wanted to be him. And I wanted my own Yew Tree.

Cooking would have remained a hobby if I hadn’t stumbled across old footage of Michelin chef Marco Pierre White preparing a stuffed pig’s trotter on YouTube. It was an audacious dish and maybe even a bit sinister. It looked a little like a stubby, sun-baked human hand on a platter. I loved how the deft skill of an unlikely genius and a few choice ingredients transformed a cheap cut of meat into a beautiful plate. The dish was transcendent to me, and in a rough kind of way, so was its creator. White smoked. White sneered. White swore. He was handsome. I could envision him swaggering around his Hampshire restaurant, the Yew Tree Inn, dropping exquisite plates of food in front of wealthy customers with all the bombast of a star footballer. As he got older and no longer cooked in the kitchen, he was known to hang about the bar and drink cider with customers, at times with a .22 rifle close by in case he had the sudden urge to go rabbit hunting. To me, Marco Pierre White was inspirational. I wanted to be him. And I wanted my own Yew Tree.I soon joined the burgeoning ranks of the know-it-all gourmand. I owned fancy knives. I photographed my food. I had a subscription to Lucky Peach. I had a well-thumbed copy of Kitchen Confidential and a demi-glace-spattered copy of The French Laundry Cookbook. At work, I had trouble concentrating on spreadsheets and instead found myself scribbling menus on graph paper. I could picture a quaint dining room with wooden tables, scalloped plates and plaid napkins. I even came up with the perfect name: the Beech Tree, inspired by the Yew Tree. I naïvely figured I could do it as well as the restaurant lifers, the tattooed dude-chefs and the nut-busting empire builders. What I lacked in experience I could make up for in enthusiasm.

In 2011, I applied to operate a booth at the Toronto Underground Food Market, a short-lived festival, known as TUM, where home cooks could sell their culinary creations to the public. I served mini-panko-crusted codfish cakes with green pea pesto, gourmet pork belly sandwiches, and wild mushroom and black pudding hash. I slogged through each step of thrice-cooked English chips, my fingers cramping so severely from peeling 100 pounds of potatoes that I almost called 911. In the end, I fed 400 people, and they liked my food. Several local bloggers wrote about my dishes. It was an adrenalin rush like no other. I lost money, but I didn’t care. My dream was gnawing at my insides.

Eighty per cent of first-time restaurateurs fail. I knew this. Opening a restaurant was the least sensible, dumbest thing I could do. My wife, Dorothy, a daycare worker, was coasting toward the end of a maternity leave, and we had two kids to feed. I was in no position to take a risk. But if it succeeded, I could make more money than any office job had ever paid me. We could enjoy a better lifestyle and maybe buy a nicer house. Plus, I’d be doing what I loved.

I pitched the concept to Dorothy, explaining that I would be front of house, designing the menu, signing cheques and glad-handing customers. I told her about a guy I had met at TUM who had launched a successful restaurant and still made it home in time to tuck in the kids every night. I proposed that she work alongside me, hosting the lunch service while our girls were at school, and I would look after the dinner service. We could run errands in the mornings, maybe sneak away for breakfast at the competition and write it off as research. Eventually, she embraced my dream, too. Now I just needed to find the money.

Six months later, an opportunity arose. My position at Telefilm, a Crown corporation, was eliminated. I was offered a lateral step, but if I walked away, I would be able to cash out $60,000 from my $130,000 pension. I could already see the tufted banquettes, the Victorian wallpaper, the brass beer taps—and me, a rifle slung over my shoulder, a pint of cider in hand. As my last day approached, I brought up my idea over drinks with a friend named Jameson, who owned a popular west-end bar. After some talk about which craft beers I should offer, he turned serious. “Are you sure you want to do this?” he asked. “I don’t think you know what you’re getting yourself into.” I smiled, drained my pint glass. “You pulled it off,” I said. “Why can’t I?”

by Robert Maxwell, Toronto Life | Read more:

Image: Dave Gillespie

Are Facebook, Twitter, and Google American Companies?

On Tuesday’s technology-executive hearings before the Senate Intelligence Committee, a key tension at the heart of the internet emerged: Do American tech companies, such as Twitter, Facebook, and Google, operate as American companies? Or are they in some other global realm, maybe in some place called cyberspace?

In response to a tough line of questions from Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas, Twitter’s acting general counsel, Sean Edgett, gave two conflicting answers within a couple of minutes. Cotton pressed Edgett on Twitter’s decision to cut off the CIA’s access to alerts derived from the Twitter-data fire hose, which is provided through a company it partially owns, Dataminr, while the companies reportedly still allowed the Russian media outlet RT to continue using the service for some time.

In response to a tough line of questions from Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas, Twitter’s acting general counsel, Sean Edgett, gave two conflicting answers within a couple of minutes. Cotton pressed Edgett on Twitter’s decision to cut off the CIA’s access to alerts derived from the Twitter-data fire hose, which is provided through a company it partially owns, Dataminr, while the companies reportedly still allowed the Russian media outlet RT to continue using the service for some time.

“Do you see an equivalency between the Central Intelligence Agency and the Russian intelligence services?,” Cotton asked.

“We’re not offering our service for surveillance to any government,” Edgett responded.

“So you will apply the same policy to our intelligence community that you’d apply to an adversary’s intelligence services?,” Cotton asked again.

“As a global company, we have to apply our policies consistently,” Edgett replied.

Cotton then turned to WikiLeaks, which the Intelligence Committee has designated as a nonstate hostile intelligence agency, asking why it had been operating “uninhibited” on Twitter.

“Is it bias to side with America over our adversaries?,” Cotton demanded.

“We’re trying to be unbiased around the world,” Edgett said. “We’re obviously an American company and care deeply about the issues we’re talking about today, but as it relates to WikiLeaks or other accounts like it, we make sure they are in compliance with our policies just like every other account.”

I’ve added the emphases within Edgett’s foregoing responses because they highlight the contradiction at the heart of these global communication services, which happen to be headquartered in the state of California. Twitter is both a global company and an American company, and the way it has resolved this contradiction is to declare its allegiance to ... its own policies.

There are reasons for this. In the wake of the Snowden revelations, social-media users became aware that the data-collection machines that Google, Facebook, Twitter, and others had created to target advertising could just as easily be used to target surveillance. They’d created perfect surveillance services, which, as Senator Mark Warner of Virginia and others noted on Tuesday, “know more about Americans than the U.S. government.” (...)

Across the board, the companies resisted attempts by various Senators to get them to say that action by state actors should be placed in a different category from other misuses of their social-networking and advertising systems. Though it’s obvious that the companies don’t want to create new rules or have new rules imposed upon them, these deflections seemed to make clear that what Senators on both sides of the aisle find themselves objecting to is not the specific Russian revelations, but what the companies’ responses expose about the very nature of the internet business: It amasses data about people—American citizens—that anyone can use to sell them stuff. It’s effective, automated, and has only a coincidental relationship with the goals of nations.

[ed. See also: The Web Began Dying in 2014, Here's How]

In response to a tough line of questions from Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas, Twitter’s acting general counsel, Sean Edgett, gave two conflicting answers within a couple of minutes. Cotton pressed Edgett on Twitter’s decision to cut off the CIA’s access to alerts derived from the Twitter-data fire hose, which is provided through a company it partially owns, Dataminr, while the companies reportedly still allowed the Russian media outlet RT to continue using the service for some time.

In response to a tough line of questions from Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas, Twitter’s acting general counsel, Sean Edgett, gave two conflicting answers within a couple of minutes. Cotton pressed Edgett on Twitter’s decision to cut off the CIA’s access to alerts derived from the Twitter-data fire hose, which is provided through a company it partially owns, Dataminr, while the companies reportedly still allowed the Russian media outlet RT to continue using the service for some time.“Do you see an equivalency between the Central Intelligence Agency and the Russian intelligence services?,” Cotton asked.

“We’re not offering our service for surveillance to any government,” Edgett responded.

“So you will apply the same policy to our intelligence community that you’d apply to an adversary’s intelligence services?,” Cotton asked again.

“As a global company, we have to apply our policies consistently,” Edgett replied.

Cotton then turned to WikiLeaks, which the Intelligence Committee has designated as a nonstate hostile intelligence agency, asking why it had been operating “uninhibited” on Twitter.

“Is it bias to side with America over our adversaries?,” Cotton demanded.

“We’re trying to be unbiased around the world,” Edgett said. “We’re obviously an American company and care deeply about the issues we’re talking about today, but as it relates to WikiLeaks or other accounts like it, we make sure they are in compliance with our policies just like every other account.”

I’ve added the emphases within Edgett’s foregoing responses because they highlight the contradiction at the heart of these global communication services, which happen to be headquartered in the state of California. Twitter is both a global company and an American company, and the way it has resolved this contradiction is to declare its allegiance to ... its own policies.

There are reasons for this. In the wake of the Snowden revelations, social-media users became aware that the data-collection machines that Google, Facebook, Twitter, and others had created to target advertising could just as easily be used to target surveillance. They’d created perfect surveillance services, which, as Senator Mark Warner of Virginia and others noted on Tuesday, “know more about Americans than the U.S. government.” (...)

Across the board, the companies resisted attempts by various Senators to get them to say that action by state actors should be placed in a different category from other misuses of their social-networking and advertising systems. Though it’s obvious that the companies don’t want to create new rules or have new rules imposed upon them, these deflections seemed to make clear that what Senators on both sides of the aisle find themselves objecting to is not the specific Russian revelations, but what the companies’ responses expose about the very nature of the internet business: It amasses data about people—American citizens—that anyone can use to sell them stuff. It’s effective, automated, and has only a coincidental relationship with the goals of nations.

by Alexis C. Madrigal, The Atlantic | Read more:

Image: Jacquelyn Martin / AP[ed. See also: The Web Began Dying in 2014, Here's How]

Labels:

Business,

Economics,

Government,

Politics,

Security,

Technology

Sunday, November 5, 2017

He’s So Fined

George Harrison v. The Chiffons. (Opinion: Bright Tunes Music Corp. v. Harrisongs Music Ltd.)

This is an action in which it is claimed that a successful song, “My Sweet Lord,” listing George Harrison as the composer, is plagiarized from an earlier successful song, “He’s So Fine,” composed by Ronald Mack, recorded by a singing group called The Chiffons, the copyright of which is owned by plaintiff, Bright Tunes Music Corp.

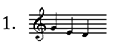

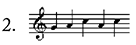

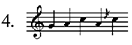

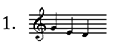

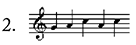

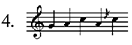

“He’s So Fine,” recorded in 1962, is a catchy tune consisting essentially of four repetitions of a very short basic musical phrase, sol-mi-re (hereinafter motif A), altered as necessary to fit the words, followed by four repetitions of another short basic musical phrase, sol-la-do-la-do (hereinafter motif B). While neither motif is novel, the four repetitions of A, followed by four repetitions of B, is a highly unique pattern. In addition, in the second use of the motif B series, there is a grace note inserted making the phrase go sol-la-do-la-re-do.

“My Sweet Lord,” recorded first in 1970, also uses the same motif A (modified to suit the words) four times, followed by motif B, repeated three times, not four. In place of the fourth repetition of motif B in “He’s So Fine,” “My Sweet Lord” has a transitional passage of musical attractiveness of the same approximate length, with the identical grace note in the identical second repetition. The harmonies of both songs are identical.

“My Sweet Lord,” recorded first in 1970, also uses the same motif A (modified to suit the words) four times, followed by motif B, repeated three times, not four. In place of the fourth repetition of motif B in “He’s So Fine,” “My Sweet Lord” has a transitional passage of musical attractiveness of the same approximate length, with the identical grace note in the identical second repetition. The harmonies of both songs are identical.

George Harrison, a former member of The Beatles, was aware of “He’s So Fine.” In the United States, it was No. 1 on the Billboard charts for five weeks; in England, Harrison’s home country, it was No. 12 on the charts on June 1, 1963, a date upon which one of the Beatles songs was, in fact, in first position. For seven weeks in 1963, “He’s So Fine” was one of the top hits in England.

According to Harrison, the circumstances of the composition of “My Sweet Lord” were as follows. Harrison and his group, which includes an American black gospel singer named Billy Preston, were in Copenhagen on a singing engagement. There was a press conference involving the group going on backstage. Harrison slipped away from the press conference and went to a room upstairs and began “vamping” some guitar chords, fitting on to the chords he was playing the words hallelujah and Hare Krishna in various ways. During the course of this vamping, he was alternating between what musicians call a Minor II chord and a Major V chord.

At some point, germinating started and he went down to meet with others of the group, asking them to listen, which they did, and everyone began to join in, taking first hallelujah and then Hare Krishna and putting them into four-part harmony. Harrison obviously started using the hallelujah, etc., as repeated sounds, and from there developed the lyrics, to wit, “My sweet Lord,” “Dear, dear Lord,” etc. In any event, from this very free-flowing exchange of ideas, with Harrison playing his two chords and everybody singing “Hallelujah” and “Hare Krishna,” there began to emerge the “My Sweet Lord” text idea, which Harrison sought to develop a little bit further during the following week as he was playing it on his guitar. Thus developed motif A and its words interspersed with “Hallelujah” and “Hare Krishna.”

Approximately one week after the idea first began to germinate, the entire group flew back to London because they had earlier booked time to go to a recording studio with Billy Preston to make an album. In the studio, Preston was the principal musician. Harrison did not play in the session. He had given Preston his basic motif A with the idea that it be turned into a song, and was back and forth from the studio to the engineer’s recording booth, supervising the recording “takes.” Under circumstances that Harrison was utterly unable to recall, while everybody was working toward a finished song, in the recording studio, somehow or other the essential three notes of motif A reached polished form.

Similarly, it appears that motif B emerged in some fashion at the recording session as did motif A. This is also true of the unique grace note in the second repetition of motif B.

The Billy Preston recording, listing George Harrison as the composer, was thereafter issued by Apple Records. The music was then reduced to paper by someone who prepared a “lead sheet” containing the melody, the words, and the harmony for the United States copyright application.

Seeking the wellsprings of musical composition—why a composer chooses the succession of notes and the harmonies he does—whether it be George Harrison or Richard Wagner—is a fascinating inquiry. It is apparent from the extensive colloquy between the court and Harrison covering forty pages in the transcript that neither Harrison nor Preston was conscious of the fact that they were using the “He’s So Fine” theme. However, they in fact were, for it is perfectly obvious to the listener that in musical terms, the two songs are virtually identical except for one phrase. There is motif A used four times, followed by motif B, four times in one case, and three times in the other, with the same grace note in the second repetition of motif B.

What happened? I conclude that the composer, in seeking musical materials to clothe his thoughts, was working with various possibilities. As he tried this possibility and that, there came to the surface of his mind a particular combination that pleased him as being one he felt would be appealing to a prospective listener; in other words, that this combination of sounds would work. Why? Because his subconscious knew it already had worked in a song his conscious mind did not remember. Having arrived at this pleasing combination of sounds, the recording was made, the lead sheet prepared for copyright, and the song became an enormous success. Did Harrison deliberately use the music of “He’s So Fine”? I do not believe he did so deliberately. Nevertheless, it is clear that “My Sweet Lord” is the very same song as “He’s So Fine” with different words, and Harrison had access to “He’s So Fine.” This is, under the law, infringement of copyright, and is no less so even though subconsciously accomplished.

3. All the experts agreed on this.

5. This grace note, as will be seen infra, has a substantial significance in assessing the claims of the parties hereto.

6. Expert witnesses for the defendants asserted crucial differences in the two songs. These claimed differences essentially stem, however, from the fact that different words and number of syllables were involved. This necessitated modest alterations in the repetitions or the places of beginning of a phrase, which, however, has nothing to do whatsoever with the essential musical kernel that is involved.

7. Preston recorded the first Harrison copyrighted recording of “My Sweet Lord,” of which more infra, and from his musical background was necessarily equally aware of “He’s So Fine.”

8. These words ended up being a “responsive” interjection between the eventually copyrighted words of “My Sweet Lord.” In “He’s So Fine,” The Chiffons used the sound dulang in the same places to fill in and give rhythmic impetus to what would otherwise be somewhat dead spots in the music.

9. It is of interest, but not of legal significance, in my opinion, that when Harrison later recorded the song himself, he chose to omit the little grace note, not only in his musical recording but in the printed sheet music that was issued following that particular recording. The genesis of the song remains the same, however modestly Harrison may have later altered it. Harrison, it should be noted, regards his song as that which he sings at the particular moment he is singing it and not something that is written on a piece of paper.

“He’s So Fine,” recorded in 1962, is a catchy tune consisting essentially of four repetitions of a very short basic musical phrase, sol-mi-re (hereinafter motif A), altered as necessary to fit the words, followed by four repetitions of another short basic musical phrase, sol-la-do-la-do (hereinafter motif B). While neither motif is novel, the four repetitions of A, followed by four repetitions of B, is a highly unique pattern. In addition, in the second use of the motif B series, there is a grace note inserted making the phrase go sol-la-do-la-re-do.

“My Sweet Lord,” recorded first in 1970, also uses the same motif A (modified to suit the words) four times, followed by motif B, repeated three times, not four. In place of the fourth repetition of motif B in “He’s So Fine,” “My Sweet Lord” has a transitional passage of musical attractiveness of the same approximate length, with the identical grace note in the identical second repetition. The harmonies of both songs are identical.