You see, Tesla is different. It just reported another doozie, a loss of $408 million in the second quarter, after its $702 million loss in the first quarter, for a total loss in the first half of $1.1 billion. In its 14-year history, it has never generated an annual profit.

It has real and popular products and surging sales, but it subsidizes each of those sales with investor money. And here’s where it’s different this time: investors don’t care. They dig how the company has been consistently overpromising and underdelivering. They dig the chaos at the top. They dig everything that should scare them off.

Yeah, its shares plunged [TSLA] 11% afterhours today, but that takes those shares only down to where they’d been on May 1. Big deal. Shares are down 32% from the peak. But their peak should have been a small fraction of that. Even today, the company is still valued at over $40 billion.

Tesla lacks a viable business model in the classic sense. Its business model is a new business model of just burning investor cash that it raises via debt and equity offerings on a near-annual basis because investors encourage it to do that, and love it for it, and eagerly hand it more money to burn, and they’re rewarding each other by keeping the share price high. It’s just a game, you see. And nothing else matters.

Then there is Boeing [BA]. It just reported the largest quarterly loss in its history of $2.9 billion due to a nearly $5-billion charge related to its newest bestselling all-important 737 Max, two of which crashed, killing 346 people, due to the way the plane is designed. The flight-control software that is supposed to mitigate this design issue is not working properly. And a software fix that is acceptable to regulators remains elusive.

The plane has been grounded globally since March. No one, especially not the regulators, can afford a third crash. So today, Boeing announced that it may further cut production of the plane or suspend it altogether if the delays continue to drag out. This is big enough to start impacting US GDP.

The entire 737 Max episode has been tragic from the first minute, and the cost in human lives has been huge, and it has cost and continues to cost billions of dollars to deal with, among calls that the plane should never fly again.

And what does Boeing’s share price do? It dipped 3% today and is up 2% from a year ago, before all this happened. In essence, two crashes and the grounding of its bestselling plane, and the potential suspension of production of this plane, and its uncertain future … and the stock has ticked up over a 12-month period.

Instead of spending the resources necessary to design a modern plane from ground up, Boeing kept basing its new models on versions of its many-decades-old 737 airframe that wasn’t designed at all for what it is being used for today. This was a decision Boeing made to save some money and pump up its share price.

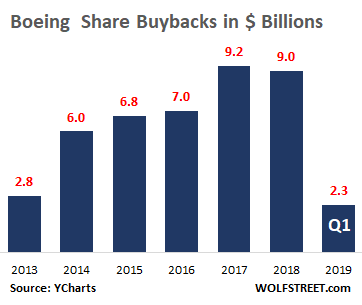

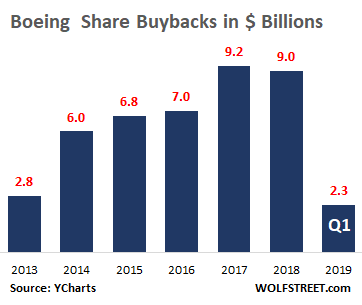

But here we go: From 2013 through Q1 2019, Boeing has blown a mind-boggling $43 billion on share buybacks (buyback data via YCharts):

Blowing these $43 billion on share buybacks has caused Boeing to have a “total equity” of a negative $5 billion. In other words, it has $5 billion more in liabilities than in assets. This company is out of wriggle room. If it can’t borrow enough money to make payroll, it’s over.

But nothing matters.

If Boeing had invested some of this money that it blew on share buybacks to design a new modern plane from ground up to replace the ancient 737 airframe, these tragedies could have been prevented, and Boeing wouldn’t have this nightmare on its hands. But the corporate cost-cutters and financial engineers, rather than real engineers, had the final word.

Markets don’t care about any of this. They don’t care about real engineers either. They love corporate cost-cutters and financial engineers. They want share buybacks, and if something bad happens, they’ll overlook the $5 billion to pay for the fallout because it’s just a “one-time item.”

And now Boeing still has this plane, instead of a modern plane, and the history of this plane is now tainted, as is its brand, and by extension, that of Boeing. But markets blow that off too. Nothing matters.

Companies are getting away each with their own thing. There are companies that are losing a ton of money and are burning tons of cash, with no indications that they will ever make money. And market valuations are just ludicrous.

Yeah, its shares plunged [TSLA] 11% afterhours today, but that takes those shares only down to where they’d been on May 1. Big deal. Shares are down 32% from the peak. But their peak should have been a small fraction of that. Even today, the company is still valued at over $40 billion.

Tesla lacks a viable business model in the classic sense. Its business model is a new business model of just burning investor cash that it raises via debt and equity offerings on a near-annual basis because investors encourage it to do that, and love it for it, and eagerly hand it more money to burn, and they’re rewarding each other by keeping the share price high. It’s just a game, you see. And nothing else matters.

Then there is Boeing [BA]. It just reported the largest quarterly loss in its history of $2.9 billion due to a nearly $5-billion charge related to its newest bestselling all-important 737 Max, two of which crashed, killing 346 people, due to the way the plane is designed. The flight-control software that is supposed to mitigate this design issue is not working properly. And a software fix that is acceptable to regulators remains elusive.

The plane has been grounded globally since March. No one, especially not the regulators, can afford a third crash. So today, Boeing announced that it may further cut production of the plane or suspend it altogether if the delays continue to drag out. This is big enough to start impacting US GDP.

The entire 737 Max episode has been tragic from the first minute, and the cost in human lives has been huge, and it has cost and continues to cost billions of dollars to deal with, among calls that the plane should never fly again.

And what does Boeing’s share price do? It dipped 3% today and is up 2% from a year ago, before all this happened. In essence, two crashes and the grounding of its bestselling plane, and the potential suspension of production of this plane, and its uncertain future … and the stock has ticked up over a 12-month period.

Instead of spending the resources necessary to design a modern plane from ground up, Boeing kept basing its new models on versions of its many-decades-old 737 airframe that wasn’t designed at all for what it is being used for today. This was a decision Boeing made to save some money and pump up its share price.

But here we go: From 2013 through Q1 2019, Boeing has blown a mind-boggling $43 billion on share buybacks (buyback data via YCharts):

Blowing these $43 billion on share buybacks has caused Boeing to have a “total equity” of a negative $5 billion. In other words, it has $5 billion more in liabilities than in assets. This company is out of wriggle room. If it can’t borrow enough money to make payroll, it’s over.

But nothing matters.

If Boeing had invested some of this money that it blew on share buybacks to design a new modern plane from ground up to replace the ancient 737 airframe, these tragedies could have been prevented, and Boeing wouldn’t have this nightmare on its hands. But the corporate cost-cutters and financial engineers, rather than real engineers, had the final word.

Markets don’t care about any of this. They don’t care about real engineers either. They love corporate cost-cutters and financial engineers. They want share buybacks, and if something bad happens, they’ll overlook the $5 billion to pay for the fallout because it’s just a “one-time item.”

And now Boeing still has this plane, instead of a modern plane, and the history of this plane is now tainted, as is its brand, and by extension, that of Boeing. But markets blow that off too. Nothing matters.

Companies are getting away each with their own thing. There are companies that are losing a ton of money and are burning tons of cash, with no indications that they will ever make money. And market valuations are just ludicrous.

by Wolf Richter, Wolf Street | Read more:

Image: YCharts and Wolf Street

[ed. See also: The Companies with the Most Debt in America (Wolf Street).]