Just as California is so often viewed from afar as either glittering paradise or dystopian disaster, so Kamala Harris was crowned as the perfect Democrat for 2020.

Like her state, Senator Harris’s story up close is both more prosaic and more nuanced than the shiny image built in part on misperceptions about California. Now that she has dropped out of the presidential race, the legacy of her campaign may be what the candidacy illustrates about the complexity and reality of politics in the Golden State. (...)

California has had, by design, weak political parties, epitomized by the current system that replaced traditional primaries with an election in which voters choose the “top two” candidates, who then face off on the November ballot. San Francisco is an anomaly, the one metropolis where politics is a sport. Political machines have flourished in the city since the late 19th century, when Christopher Buckley, known as the Blind Boss, consolidated power from the back room of his saloon by establishing a patronage system. A century later, Kamala Harris rooted herself in the political establishment and forged connections with help from her longtime mentor and onetime boyfriend Willie Brown, the powerful Assembly speaker and then San Francisco mayor.

California has had, by design, weak political parties, epitomized by the current system that replaced traditional primaries with an election in which voters choose the “top two” candidates, who then face off on the November ballot. San Francisco is an anomaly, the one metropolis where politics is a sport. Political machines have flourished in the city since the late 19th century, when Christopher Buckley, known as the Blind Boss, consolidated power from the back room of his saloon by establishing a patronage system. A century later, Kamala Harris rooted herself in the political establishment and forged connections with help from her longtime mentor and onetime boyfriend Willie Brown, the powerful Assembly speaker and then San Francisco mayor.Those connections helped the young prosecutor become a boldface name in the society pages and in the copy of the legendary columnist Herb Caen. Ms. Harris won her first race in 2003, unseating the incumbent district attorney, with support from law enforcement unions, The San Francisco Chronicle and the political and social elite of San Francisco.

From the small city with outsize visibility, she built a national profile. In 2008, Ms. Harris was California co-chairwoman for her friend Barack Obama; within days of his historic victory, she announced her candidacy for California attorney general, a race still two years away. Oprah Winfrey put her on O magazine’s “Power List.” A column in USA Today pronounced her “the female Barack Obama,” “destined to become a commanding presence in the political life of this country.”

Perhaps one of the greatest fallacies about California politics is the assumption that its Democratic leaders are by definition die-hard liberals. By necessity, Democrats who win statewide have actually been moderates. That remains true even in an era when no Republican has won statewide since 2006. Last year, for example, Senator Dianne Feinstein trounced her liberal opponent, despite his endorsement by the state Democratic Party.

Even Gavin Newsom, the most liberal governor in decades, got his start in San Francisco by defeating a Green Party candidate for mayor, the same year Ms. Harris unseated the city’s progressive district attorney by running a tough-on-crime campaign. In her 2010 race for attorney general she arguably ran to the right of her Republican opponent on some issues. He championed efforts to ease the state’s three-strikes law and later supported a successful ballot initiative to that end; Ms. Harris, by then attorney general, declined to take a position.

As attorney general, she disappointed California liberals through both actions and the lack of action. That did not hamper her ability to burnish her national credentials. She addressed the 2012 Democratic National Convention in a prime-time slot. Her name was floated as a potential United States attorney general, even a Supreme Court justice.

Yet she remained largely unknown in California — a function of the staggering size of a state of almost 40 million where the principal way to gain exposure requires television ads in a dozen media markets, at a cost of upward of $4.5 million a week. When Ms. Harris ran for the United States Senate in 2016, six out of 10 registered voters had no impression of her, although she had been attorney general for almost six years. In recent polls, about a quarter of voters still had no opinion.

That reality undercut a key argument cited by pundits who labeled her an instant front-runner when she entered the presidential race. Their scenarios assumed she would do well in the delegate-rich California primary, moved up to March to have more impact on the race. (...)

And then there is the role of California in the age of President Trump. His victory coincided with Ms. Harris’s election to the Senate and fueled a sense of inevitability about her candidacy. She was the prosecutor who could take on the president. From the state that had become the heart of the resistance came the candidacy fueled by anti-Trump anger and California glitter.

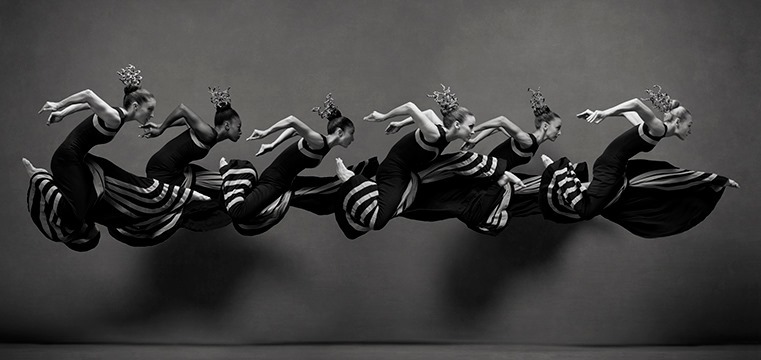

At her January kickoff in Oakland, a huge crowd of all ages and races waved flags, pumped fists, teared up. They cheered her passion, her toughness and her rhetoric. But above all they were cheering for a woman who would take on the man whose name she never mentioned.

This, too, was not quite what it seemed. It was easy to conflate antipathy to Mr. Trump with support for Ms. Harris. By the time she appeared in Oakland eight months later at a low-key event to open her campaign office, the questions were about polls that showed her running a distant fourth in her home state, fourth even in the Bay Area, where they knew her best.

by Miriam Pawel, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Damon Winter/The New York Times