[ed. Sorry for the lack of posts lately. Maybe it's just burnout. So much of what you read in the media these days is just junk - endless political squabbling and regurgitated stories, apocalypse, celebrities, atrocities, crime, indignation, heartbreak, economic insecurity, even history (with armies of freelancers just looking for something to write about). Too many people chasing the same themes and stories for clicks. I'll have more on this later, but for now check out the archives or just do something that gives you enjoyment, like maybe reading a good book (I'm currently reading The Overstory by Richard Powers and can highly recommend it.)]

Thursday, December 12, 2019

Wednesday, December 11, 2019

Fowl Play

JUNEAU -- Brad Austin was drinking coffee and getting ready for work Friday morning when he heard a strange popping sound, like metal in a clothes dryer.

The Juneau resident caught sight of an orange glow through a window. He poked his head out a side door and saw his front porch on fire.

As he made a hurried call to 911, a fire extinguisher and garden hose got involved. After firefighters arrived, they found the fire’s cause: A pair of dead ducks hanging from his porch light.

As he made a hurried call to 911, a fire extinguisher and garden hose got involved. After firefighters arrived, they found the fire’s cause: A pair of dead ducks hanging from his porch light.“Oh yeah, they got revenge big time,” Austin said Tuesday.

“It was definitely an unusual fire,” said Rich Etheridge, chief of Capital City Fire/Rescue, Juneau’s fire department. “It took them a little while to figure out what had happened.”

Austin’s 26-year-old son, Lyman, is an avid duck hunter and frequently brings his catch back home for drying and butchering. But last year, the family painted their home, and at that time, they pulled the nails where Lyman usually hung his ducks.

With the nails gone, he started hanging them from the porch light fixture using a nylon strap. That wasn’t a problem until Thursday night, when the family left the light on overnight.

“That was the big thing. I think I had gone to bed first and he hadn’t turned the light off,” Austin said.

According to firefighters’ account of events, the ducks’ waterlogged feathers dried out and began to smolder. At a certain point, the natural oils in the ducks’ feathers ignited, turning into wicks for duck-scented candles as fire consumed the ducks’ fat.

The flames ignited the home’s wood siding and sent fire toward the eaves. The burning ducks melted through their hanging strap, landing on a rubber doormat that also caught fire.

As Austin fought the fire, he shouted for his son to get out of the shower, grab their dogs and get out of the house. None were hurt. The fire was confined to the home’s entryway, which Austin said he had wanted to remodel anyway.

“That’s why we can laugh at it. It’s not like half of my house burned down,” Austin said.

Juneau fire marshal Dan Jager said the situation could have been more serious if the family had been asleep or away from the home. The house did not have installed smoke detectors, and there are no nearby neighbors.

Deputy fire chief Travis Mead said the older home’s construction also inhibited the spread of the fire, and a newer home would not have fared as well.

by James Brooks, ADN | Read more:

Image: Brad Austin

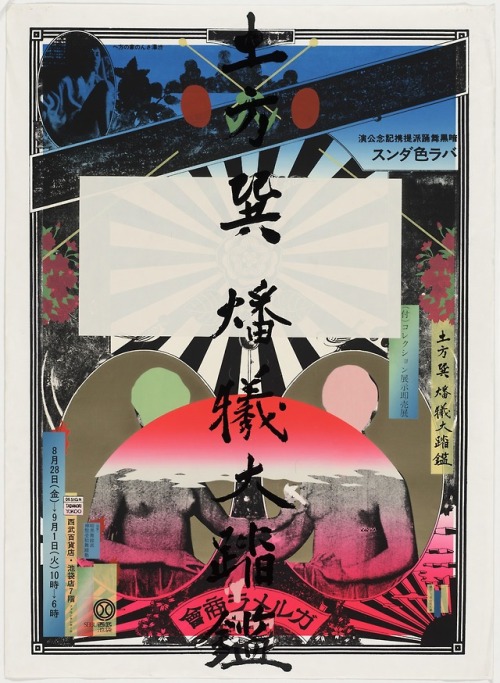

Art Eats Art

'It is something deeper': David Datuna on why he ate the $120,000 banana (The Guardian)

Image: Rhona Wise/EPA

[ed. You can't make this stuff up. Once in a while there's a glitch in The Matrix and it reveals itself.]

[ed. You can't make this stuff up. Once in a while there's a glitch in The Matrix and it reveals itself.]

Tuesday, December 10, 2019

Round Tree, Square Hole

Planting a tree is one of the easiest ways you can make a lasting difference to your local environment and, depending on the species, enjoy decades of flowers, fruit and autumn colour – all in return for a modest outlay and a few minutes’ work.

Although putting a tree in the ground might not sound like rocket science, in recent decades scientific research has overhauled much of the traditional wisdom about planting saplings, including some ideas that sound a little strange. So, let me explain why science proves that it’s better to plant trees in square holes.

Although putting a tree in the ground might not sound like rocket science, in recent decades scientific research has overhauled much of the traditional wisdom about planting saplings, including some ideas that sound a little strange. So, let me explain why science proves that it’s better to plant trees in square holes.Traditionally, trees were planted in round holes, perhaps because their trunks are round, as is the spread of their canopies. It was just one of those seemingly obvious, unquestioned assumptions. But here’s what happens to the tree’s roots when you plant them in a round hole, especially one filled with lots of rich compost and fertiliser, as the old guide books suggest. The little sapling will rapidly start growing new roots that will spread out into the rich, fluffy growing media, giving you excellent early success. However, once they hit the comparatively poorer and compacted soil at the perimeter of the hole, the roots will react by snaking along the edge of the hole’s edge in search of more ideal growing conditions.

Eventually, this spiralling action around the limits of the hole will create a circular root system, with the plants essentially acting much as they do when grown in a container. Once the roots mature they will thicken and harden into a tight ring, creating an underground girdle that will choke the plant, eventually resulting in the severe stunting and even death of your treasured tree.

The very simple and counterintuitive act of digging a square planting hole will dramatically reduce the chances of this happening. This is because systematic planting trials have shown that roots are not that good at growing round corners. When they hit the tight, 90-degree angle of your square hole, instead of sneaking around to create a spiral, they flare out of the planting hole to colonise the native soil.

by James Wong, The Guardian | Read more:

Image: Liam Anderstrem/PAMonday, December 9, 2019

Life Blood of the Economy

For much of the world, donating blood is purely an act of solidarity; a civic duty that the healthy perform to aid others in need. The idea of being paid for such an action would be considered bizarre. But in the United States, it is big business. Indeed, in today’s wretched economy, where around 130 million Americans admit an inability to pay for basic needs like food, housing or healthcare, buying and selling blood is of the few booming industries America has left.

The number of collection centers in the United States has more than doubled since 2005 and blood now makes up well over 2 percent [ed. emphasis added] of total U.S. exports by value. To put that in perspective, Americans’ blood is now worth more than all exported corn or soy products that cover vast areas of the country’s heartland. The U.S. supplies fully 70 percent of the world’s plasma, mainly because most other countries have banned the practice on ethical and medical grounds. Exports increased by over 13 percent, to $28.6 billion, between 2016 and 2017, and the plasma market is projected to “grow radiantly,” according to one industry report. The majority goes to wealthy European countries; Germany, for example, buys 15 percent of all U.S. blood exports. China and Japan are also key customers.

by Alan Macleod, MPN | Read more:

Image: Dracula, Universal Studios

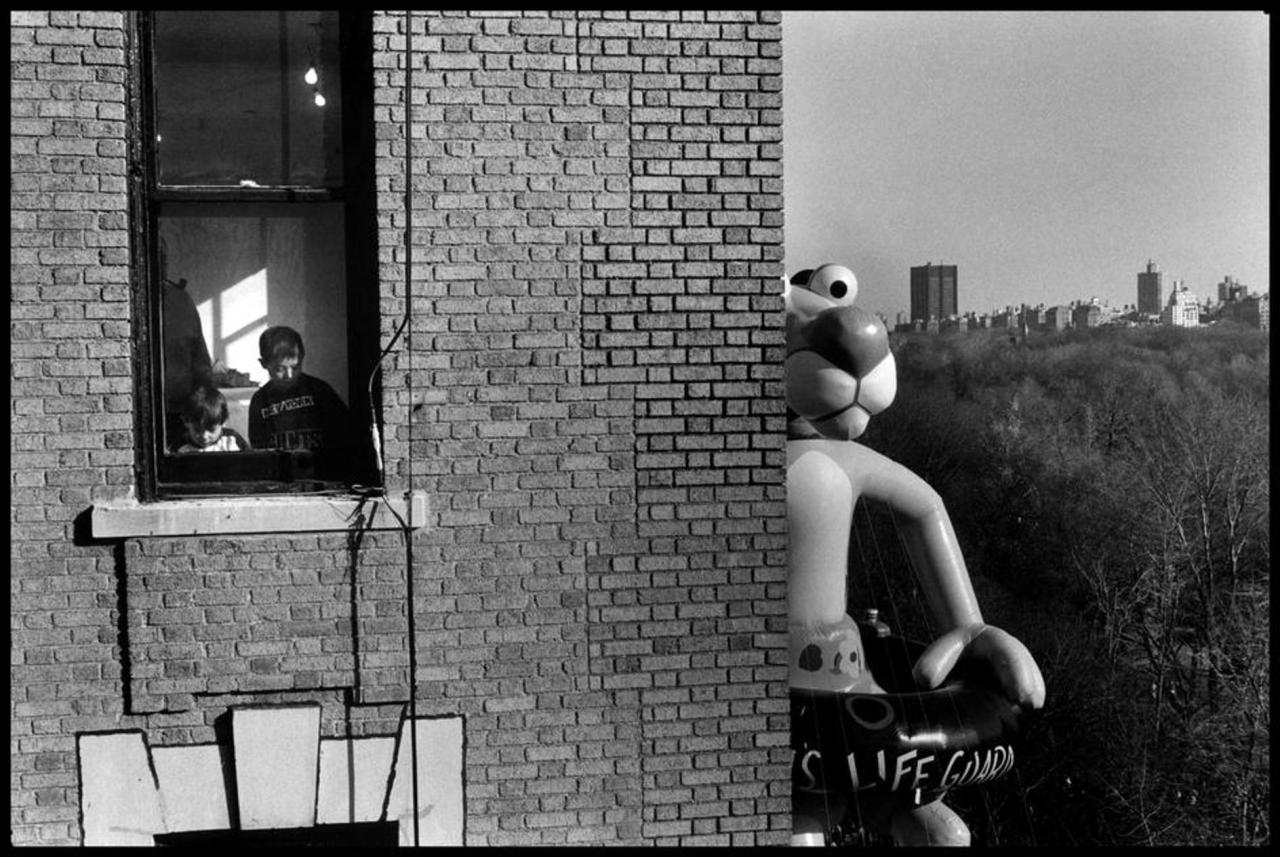

[ed. Gives new meaning (literally) to the term blood-sucking capitalism. See also: What 60 Minutes Missed: 44 Percent of U.S. Workers Earn $18,000 Per Year (The Stranger)]Naked City

I find this idea reassuring, because life here can make you feel not just unimpressive, not just peripheral, but entirely negligible. I have lived in New York for more than 22 years, which I am sorry to say is more than half my life. In that time, I have never stopped asking the question: Do I belong here? Am I woven into the tapestry, or am I a dangling thread? How does everyone seem to know one another, and where is everybody going? Why is the line at Sarabeth’s so long? Why are the libraries closed on Sundays? Was there a memo about wearing Hunter rain boots? Why are dogs not allowed in my building? Every day, I am confronted by mysteries. But if New York City is actually dependent on every last person within its boundaries, deriving not just energy but also narrative structure from all who move through it, then maybe I’m not negligible after all.

I have tried to explain to others the feeling I get on a typical day in the city — that we are all characters in some sort of Yiddish short story, but it’s unclear who are the heroes and who are the villains, whether it is a comedy or a tragedy, who are the stars, and who are merely the background. You see and hear so many things in a day. So I’ll start from the beginning — the beginning of yesterday, that is, and go through one whole day, and hope that you’ll come along for the ride.

Yesterday began like many others. I was in the check-out line at Zabar’s, and I overheard an exchange that intrigued me. A middle-aged woman in nondescript, baggy clothes, her hair a combination of layered bohemian chic and I-don’t-care gray — a West Side classic — was talking to another woman, who was younger.

Yesterday began like many others. I was in the check-out line at Zabar’s, and I overheard an exchange that intrigued me. A middle-aged woman in nondescript, baggy clothes, her hair a combination of layered bohemian chic and I-don’t-care gray — a West Side classic — was talking to another woman, who was younger.“We’ll go downtown to my place, we’ll have a cup of coffee, and we’ll talk. Later, I’ll put you in a cab. Sound good?”

I composed a silent plea. Take me too. I can’t think of any place I’d rather go than downtown to your place, for a cup of coffee. I felt strongly that this woman had curtains — big silk curtains — and her apartment had a sitting room and a poodle or two sprawled on the rug. Her place had a view of a public garden, and there was primrose in bloom, and maybe a fountain, and people smoking, and other people kissing, and a few in the midst of lovers’ spats, and rain kissed the earth, just there, in that garden. A cab! Is there anything to excite the imagination more than the hailing of a cab after someone unexpectedly asks you over for a cup of coffee? I wanted the younger woman’s problems, whatever had invited the older woman’s concern. The word “downtown” had become a cashmere shawl, one I wanted to be wrapped in immediately.

The checker put my groceries in the bag. I trudged home, feeling blue. Once again — not at the center of it, not where the action was, the discourse, the problems, the connection. At home, I made myself some coffee, but there were no silk curtains, no poodles, no conspiring or commiseration.

A short time later, I traveled south to my dance studio, Steps, which sits in a hub of Upper West Side activity. You’ve got the Beacon Theatre just across Broadway, the Ansonia just south, and next door, Fairway Market, which is a holy pilgrimage in itself. I’ll say just this: Fairway has an entire room devoted to cheese. Also: things you didn’t know you wanted, because you didn’t know they existed. Artichoke paste. Lambrusco vinegar. Garam masala. Chocolate latte balls — $1.25 a bag.

On the elevator at Steps, I witnessed an altercation. A young, paunchy man wearing earphones got on before this other woman and almost held the door for her. I say almost because he held it for a second, then let it go too soon, before she was safely inside, so the door banged into her. She didn’t need a hospital or anything, but there was no question he was in error. The elevator takes approximately three hours to get from the lobby to the third floor — where the classes are — and back. Catching the elevator is therefore a big deal, as is holding the door for that one last person who is desperate not to wait three more hours for the next ride. The woman quietly harrumphed. Message received. Wild-eyed, the paunchy man said, “I HELD THE DOOR FOR YOU.” She did not accept the falsehood. “You did NOT hold the door for me,” she replied. “You let the door SLAM on me.” Enraged, he replied, “I am not talking to you.” “It sure sounds like you are!” she shot back, and he became so angry that I prayed the elevator was almost at the third floor. I didn’t fear for her safety, but maybe a little I did. When she walked off the elevator, he cursed her. I don’t mean he used foul language, I mean he cast a hex. Sarcastically. “Hope your tendus aren’t all sickled!” he said.

Performing arts shade! (A tendus becomes sickled when you point your foot in the wrong direction, which is a gross dance error, the equivalent of a social gaffe while interacting with, say, the queen of England. You don’t want to get caught sickling your tendus.) All at once, I felt kinship with both the aggressor and the victim in this elevator standoff. I don’t know exactly what defines New Yorkers, but it has something to do with our ability to keep the rhythm of these altercations without missing a beat, like children playing double Dutch.

In the sunshine of Studio II, a motley collection of dancers was warming up for the 10 a.m. ballet class. The teacher is tall and blond and haughty — so imperious her instruction borders on camp. She speaks with a British-implied accent and adorns her daily performance with an array of hairstyles and lipsticks. Her smile is lopsided and sudden, just enough to alert us that her condescension is mostly for show. She has a fabulous accompanist and sometimes there are 100 people taking class. It’s ballet with a cabaret atmosphere, and I suspect people love this teacher because she makes them feel like party guests. The spectrum of humanity attends. At the barre, one sees principal dancers from American Ballet Theatre and New York City Ballet, so immaculately sculpted and graceful that they strike one as circus performers or possibly even figments of the imagination. Also at the barre: an elderly woman in a wig who carries her ballet shoes in a plastic bag from the liquor store.

We are all freaks in this room — spiritual cousins of sorts, worshipping at the same church. Here we find rapport and community, gossip and disdain. The mighty sylphs chat with the old loons, and the rest of us try to figure out where on this spectrum we fall. Everyone here is drawn to ballet as a monk is drawn to prayer, and this commonality surpasses — if only in this hour and a half — our jagged differences in achievement.

A tiny woman stood behind me at the barre. She smiled and said hello. She knew me from the playground I frequent with my child. How was life? How was school? What grade was my daughter in now? Good. OK. Second. Her girls were fine, she said, except for one thing. What was that? I asked. They were both enrolled at the School of American Ballet (S.A.B., as it’s known around here), and they weren’t happy. The School of American Ballet is a “feeder school” for New York City Ballet, which, for many people, is the pinnacle of the art, the highest goal, the shiniest of prestigious places. It’s also known for being a hotbed of sexism, not to mention a place keen on anorexia as a way of life. Still — New York City Ballet! My daughter takes class at another, saner place, but even at 7, she’s heard of S.A.B. It’s where the perfectly turned-out, smooth-bunned, pearl-earring-bedecked baby giraffes are going when they make a sharp turn and head into Lincoln Center. I researched when the annual audition day was — sometime in early spring. I don’t know what made me do it, except of course I do: At the center of New York City’s ineffable glory are cosmic sources of radiation — Times Square, the Chrysler Building, the grandiose arrangements of limelight hydrangeas in the main hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the School of American Ballet.

by Leslie Kendall Dye, Longreads | Read more:

Image: Homestead Studio, based off Oksana Latysheva & Vivali / Getty

Sunday, December 8, 2019

The New Age of Social Engineering

Part 1 — Ten millenniums of social engineering

A key part of my thesis is that the way our social environment is formed has changed over the course of human history, and more rapidly in recent years. How do we know that to be true? Much of the work I’m building on comes out of the accounts provided by The Secret of Our Success by Joseph Henrich, as well as Seeing Like a State by James C. Scott. There are many things that I disagree with in these works, but I think they both get to the core idea that there exist two main ways in which human society develops. One of those ways is via an evolutionary process, where some societies develop some technique that aids in survival and flourishing, pass it on, and end up growing and outcompeting other societies. The people practicing these traditions often don’t have concrete knowledge as to why they work, but they become enshrined as tradition because they help the group succeed. This goes from knowledge about what plants are edible, to complex ideas like how the group should be structured. On the other hand, there is social engineering. In social engineering, explicit models of human behavior are used to derive new social conventions and structures. Usually this doesn’t mean designing something new from whole cloth, but instead an effective synthesis of ideas that the culture has generated over time into a compelling ideological canon or into new distinct institutions.

For most of human history, we relied primarily on social evolution instead of social engineering. This was for good reason: social engineering when done poorly is very often worse than social evolution. A mother who breaks tradition and tries feeding new plants to their children because she doesn’t know of any reason those plants are harmful may discover unexpected side effects of their consumption. This reality is often referred to as Chesterton’s fence, and is often discussed as an argument in favor of traditionalism. However, much of the social and technological progress of the industrial era has through the rejection of tradition. How do we square these conflicting forces? I think that a key reason is simply because for a society to succeed in social engineering, a detailed historical record and careful specialists are usually necessary. Only in this way can new first principle knowledge be solidified and built-upon. It’s for that reason that the societies that appear the most engineered also in general tend to be those with more detailed historical records and information about other differing societies. When one is able to see the culture “from above”, that unique perspective can enable one to design an effective institutions.

For most of human history, we relied primarily on social evolution instead of social engineering. This was for good reason: social engineering when done poorly is very often worse than social evolution. A mother who breaks tradition and tries feeding new plants to their children because she doesn’t know of any reason those plants are harmful may discover unexpected side effects of their consumption. This reality is often referred to as Chesterton’s fence, and is often discussed as an argument in favor of traditionalism. However, much of the social and technological progress of the industrial era has through the rejection of tradition. How do we square these conflicting forces? I think that a key reason is simply because for a society to succeed in social engineering, a detailed historical record and careful specialists are usually necessary. Only in this way can new first principle knowledge be solidified and built-upon. It’s for that reason that the societies that appear the most engineered also in general tend to be those with more detailed historical records and information about other differing societies. When one is able to see the culture “from above”, that unique perspective can enable one to design an effective institutions.One excellent example is perhaps one of the most successful early cultural engineers, Confucius. The Great Teacher developed his unique philosophy while travelling around China and seeing various social issues, their causes, and the variety of different social structures present in China at the time. By synthesizing these insights into a central canon, he created an enduring cultural institution that was central to Chinese administration for centuries. Of course it is true that Confucianism relies heavily on tradition, and can in some ways be considered no more than a collection of various preexisting traditions, but its success indicates that it must have some quality beyond that of the constituent parts. Ultimately, Confucianism and the society it created lost supremacy because while it itself was a result of synthesis, it became unable to assimilate or change at pace with the world it inhabited. What once created a powerful bureaucratic class capable of financing great discoveries, ended up as a chain that left the society unable to appreciate the possibility of learning from outside influences. Innovation became tradition, and tradition cannot change course by its very nature.

Part 2 — Modernity

We’re going to leave behind ancient societies, because although they are a rich source of insight, others have better studied those trends in depth than I. Instead we are going to turn to look at the relatively modern. I am going to focus for a minute on the United States. For all that American Exceptionalism is a real risk, I think there is something somewhat unique and interesting about the formation of the US. Specifically, the US is one of the best examples of what I consider full social engineering. A group of people sat down in a room and set out to design, in a written legal document, how its society would function. It was a group of what can only be called engineers who set out to design structures to improve upon the governments they were aware of. They didn’t just try and say “tyranny is bad so we won’t be tyrants,” they tried to engineer complex social structures that took advantage of human behavior in order to guide the behavior of the government — independent of any single political actor. The idea of applying contractual thinking to the structure of our nations and institutions didn’t start with the US, but the US can be seen as a culmination of those ideas. This project has had varied success to say the least, but it’s notable that so many modern institutions function in this way. A group of founders get together and try to set the community’s direction at both an object and meta-level. Just as the objects and tools we use have become increasingly engineered, so too have our institutions become influenced by engineering. The evolution and design of social norms is at the heart of what we call society. I would venture to say that it is the defining feature of the human species, and of intelligent species in general. TheMachiavellian Intelligence Hypothesis posits that intelligence arose, not to better use tools or better hunt prey, but instead to better compete in the social arena. Therefore, I think it’s fair to say the top down engineering in the world of social norms faces an uphill battle to outperform the metis of the traditional culture. However, this applies much less when we turn our eyes towards the engineering of the physical spaces our cultures occupy.

Social Engineering in the context of the physical is about the design of objects and spaces in the traditional engineering sense, but with a consideration to how that design influences the group rather than the individual. It’s obvious that a designer making a chair must consider how the chair interacts with the behaviors and preferences of the person who will eventually use the chair. This same thoughtfulness should be applied, and usually is, when dealing with objects and spaces that drive social interaction. Someone trying to build a successful bar will think carefully about the layout and decoration of the space and how that will influence their patrons. They may think about other layouts they’ve seen and how they might improve on those designs in order to give the space the mood they want.The pub is undeniably a social institution, and it is designed to both encourage and discourage certain types of social behavior. Every space you interact with, from the supermarket to the sidewalk, has generations of trial, error, and improvement. That doesn’t mean every space is perfect, but it’s easy to forget the marvel that is present all around us. However, it is the process of conscious engineering that has also introduced many institutions that are detrimental to healthy communities. (...)

Part 3 — The Internet

The internet has opened up a new frontier in the design of social institution. We are designing platforms that are used by wide masses of people, that grow more quickly than any historical analog, and that provide unprecedented levers of control over discourse. Facebook was founded in 2004; ten years later there were more monthly active Facebook users than Catholics. The ability to implement a new social institution with basically no startup cost and end up with this much influence is unprecedented, and thus it’s not surprising that we’ve seen so many instances of the new social internet having issues with healthy discourse. So much of the evolutionary work that went into shaping our meatspace social institutions has been ignored during the construction of these new online spaces. Platform designers often repeat the mistakes of the High Moderns. The users of the platforms are rarely given a voice in discussions, and are frequently treated as antagonists rather than stakeholders. Worst of all, centralized platforms have very little immediate incentives to improve the quality of discourse, as network effects prevent users from easily moving to a nicer competitor. Network operators are encouraged to gain users as fast as possible, keep them in the space as long as possible to view ads, and completely ignore the social well-being of the communities that form. Additionally, online platforms provide a nigh microscopic level of control over the interactions between users. Someone designing a bar can choose the layout of the tables and the lighting, but an online platform designer can run automated testing to determine what text, fonts, and layouts best guide the user into behaving in a desired way. In the case of platforms like YouTube, complex AI systems are constantly optimizing every nanometer of the system to maximize ad revenue.

In the early days of the internet there was a lot of optimism about the ability of the web to bring people together, to form new understanding between distant peoples, and to provide an escape from tyranny. It’s important to recognize some of the successes on these fronts. I regularly communicate with people from other nations, and that has helped give me a broader view of the world and of differing cultural norms. However, anybody can see that we have failed to live up to this early promise. Most of the social spaces online were driven in design by technological constraints and financial motives, not by a consistent dedication to building prosocial institutions. The rapid expansion of the internet has left engineers struggling to make their websites function at all, let alone spend resources on deep analysis of user behaviors. Such work is only done by established players with the goal of increasing revenue, and thus almost inevitably results in a worsening of user experiences because of misaligned incentives. To fix these issues we need both philosophical changes and technological changes.

Image: Portrait of K’ung Fu-tzu (Latinised to Confucius).Copyright Bridgeman Images. via

Saturday, December 7, 2019

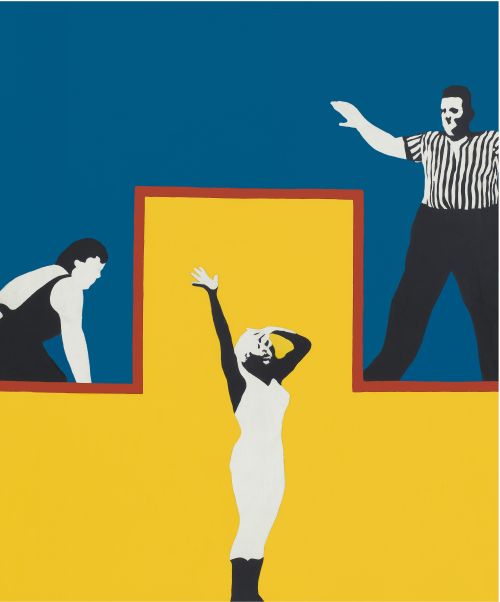

What Is The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Afraid Of?

The great irony of Amy Sherman-Palladino’s television shows is that the dialogue gushes forth with the insistence of a burst hydrant, and yet the most beguiling moments are the ones in which no one speaks at all. Midway through the third season of Amazon’s The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, a man and a woman whose chemistry has smoldered almost since the show’s inception find themselves alone, in the early hours of the morning, at a hotel. They gaze at each other. They each glance meaningfully through the open door toward a bed. They say nothing. The energy is so heightened and so loaded with expectation that I couldn’t have stopped watching if the room around me had suddenly caught on fire.

The five hours or so that preceded it, though, had mostly the opposite effect, where any scenes without Rachel Brosnahan’s unsinkable comic Midge Maisel—and even a few with her—were either inert or insufferable. What used to feel like Sherman-Palladino trademarks now come across as tics: the barrage of inane chatter; the superficial stereotyping; the overreliance on spectacle without substance, like a dinner composed entirely of cake pops. More vexing than anything, though, is how defiantly The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel refuses to have stakes. Everything plays out in the same major key. Everything—lost children, homelessness, divorce, social injustice—is just a joke, bedazzled and glib and gorgeous. This is a series so vacantly uplifting, it’s managed to transfigure Lenny Bruce into Prince Charming.

The five hours or so that preceded it, though, had mostly the opposite effect, where any scenes without Rachel Brosnahan’s unsinkable comic Midge Maisel—and even a few with her—were either inert or insufferable. What used to feel like Sherman-Palladino trademarks now come across as tics: the barrage of inane chatter; the superficial stereotyping; the overreliance on spectacle without substance, like a dinner composed entirely of cake pops. More vexing than anything, though, is how defiantly The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel refuses to have stakes. Everything plays out in the same major key. Everything—lost children, homelessness, divorce, social injustice—is just a joke, bedazzled and glib and gorgeous. This is a series so vacantly uplifting, it’s managed to transfigure Lenny Bruce into Prince Charming.

While the show has always been this way, previous seasons have always had something specific to elevate them: Midge’s talent. Over the first eight episodes, Midge evolved from serene housewife to jilted single parent to accidental comedian to blacklisted talent with breathtaking velocity. Her discovery—after her weaselly husband’s departure prompts her to take a drunken subway ride to a downtown comedy club—that she could make rooms of people laugh was the kind of fairytale moment that was easy to believe in, because Brosnahan’s performance was so entrancing. Onstage, Midge dazzles, even when she bombs. And in the first two seasons, the show seemed to suggest that Midge wasn’t satisfied being merely funny; she had the kind of ambition that can change the world she inhabits, redefining the way people think about women, comedy, and especially the two together.

But great comedy has to acknowledge darkness, which Mrs. Maisel has always resisted. The presence of Bruce as a character (played in magnetic, Emmy-winning style by Luke Kirby) seemed to suggest that Midge’s comedy might skirt the edges of propriety. But apart from a wine-soaked interlude in Episode 1 where she bared her breasts onstage and was arrested, her routine has played it safe, rarely advancing beyond the subjects of sex, failure, and men having the privilege of comfortable shoes. (...)

It’s frustrating, because the show keeps hinting that it’s edging toward more substantial fare, only to back out at the last minute. The running joke wherein strangers mistake Susie for a man wasn’t funny to begin with—now it only draws attention to how timidly the show avoids the subject of Susie herself, and her desires. When Midge accepted in Season 2 that pursuing greatness in comedy would mean sacrificing personal happiness and stability, I thought the show might be going somewhere groundbreaking. Instead, Midge dispatched with her fiancé, Benjamin (Zachary Levi), as carelessly as if she were throwing out leftovers—offscreen, and with no apparent sense of loss. Midge’s chemistry with Bruce is a potent force, but the more the series leans into it, the more I have questions about how a show this ebullient is going to eventually deal with a man who died of a morphine overdose in a Hollywood bathroom.

The five hours or so that preceded it, though, had mostly the opposite effect, where any scenes without Rachel Brosnahan’s unsinkable comic Midge Maisel—and even a few with her—were either inert or insufferable. What used to feel like Sherman-Palladino trademarks now come across as tics: the barrage of inane chatter; the superficial stereotyping; the overreliance on spectacle without substance, like a dinner composed entirely of cake pops. More vexing than anything, though, is how defiantly The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel refuses to have stakes. Everything plays out in the same major key. Everything—lost children, homelessness, divorce, social injustice—is just a joke, bedazzled and glib and gorgeous. This is a series so vacantly uplifting, it’s managed to transfigure Lenny Bruce into Prince Charming.

The five hours or so that preceded it, though, had mostly the opposite effect, where any scenes without Rachel Brosnahan’s unsinkable comic Midge Maisel—and even a few with her—were either inert or insufferable. What used to feel like Sherman-Palladino trademarks now come across as tics: the barrage of inane chatter; the superficial stereotyping; the overreliance on spectacle without substance, like a dinner composed entirely of cake pops. More vexing than anything, though, is how defiantly The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel refuses to have stakes. Everything plays out in the same major key. Everything—lost children, homelessness, divorce, social injustice—is just a joke, bedazzled and glib and gorgeous. This is a series so vacantly uplifting, it’s managed to transfigure Lenny Bruce into Prince Charming.While the show has always been this way, previous seasons have always had something specific to elevate them: Midge’s talent. Over the first eight episodes, Midge evolved from serene housewife to jilted single parent to accidental comedian to blacklisted talent with breathtaking velocity. Her discovery—after her weaselly husband’s departure prompts her to take a drunken subway ride to a downtown comedy club—that she could make rooms of people laugh was the kind of fairytale moment that was easy to believe in, because Brosnahan’s performance was so entrancing. Onstage, Midge dazzles, even when she bombs. And in the first two seasons, the show seemed to suggest that Midge wasn’t satisfied being merely funny; she had the kind of ambition that can change the world she inhabits, redefining the way people think about women, comedy, and especially the two together.

But great comedy has to acknowledge darkness, which Mrs. Maisel has always resisted. The presence of Bruce as a character (played in magnetic, Emmy-winning style by Luke Kirby) seemed to suggest that Midge’s comedy might skirt the edges of propriety. But apart from a wine-soaked interlude in Episode 1 where she bared her breasts onstage and was arrested, her routine has played it safe, rarely advancing beyond the subjects of sex, failure, and men having the privilege of comfortable shoes. (...)

It’s frustrating, because the show keeps hinting that it’s edging toward more substantial fare, only to back out at the last minute. The running joke wherein strangers mistake Susie for a man wasn’t funny to begin with—now it only draws attention to how timidly the show avoids the subject of Susie herself, and her desires. When Midge accepted in Season 2 that pursuing greatness in comedy would mean sacrificing personal happiness and stability, I thought the show might be going somewhere groundbreaking. Instead, Midge dispatched with her fiancé, Benjamin (Zachary Levi), as carelessly as if she were throwing out leftovers—offscreen, and with no apparent sense of loss. Midge’s chemistry with Bruce is a potent force, but the more the series leans into it, the more I have questions about how a show this ebullient is going to eventually deal with a man who died of a morphine overdose in a Hollywood bathroom.

by Sophie Gilbert, The Atlantic | Read more:

Image: Amazon

[ed. Love the show, she does have a point.]

[ed. Love the show, she does have a point.]

WTF is Grammar?

This is quite a jolly academic book written by a linguist for the general reader about internet language. It has already had considerable success in America. The curious thing is that it’s a book at all. Hasn’t the internet killed off books? Why isn’t it a podcast or a live download or whatever?

What is the language of the internet? Most of us have probably heard of LOL (or lol), omg, emojis and even memes, and come face to face with unconventional confections of exclamation marks, repeated letters and novelty punctuation. For people like us, top-end book lovers, the language of the internet might seem, well, rather ghastly: illiterate, limited, debased, invasive like Japanese knotweed, a frightful triffid threatening to obliterate decent standards of communication. They, the internet lovers, if they even bother to glance in our direction, will think: omg!!!!11!!! sad lol.

What is the language of the internet? Most of us have probably heard of LOL (or lol), omg, emojis and even memes, and come face to face with unconventional confections of exclamation marks, repeated letters and novelty punctuation. For people like us, top-end book lovers, the language of the internet might seem, well, rather ghastly: illiterate, limited, debased, invasive like Japanese knotweed, a frightful triffid threatening to obliterate decent standards of communication. They, the internet lovers, if they even bother to glance in our direction, will think: omg!!!!11!!! sad lol.I recently heard of somebody who no longer laughs. Instead she says ‘lol’, which might be a new internet way of laughing. An urban myth, perhaps, but there’s a common assumption that too much online activity transforms people into zombies in ‘real’ life. As is perhaps inevitable, linguists like Gretchen McCulloch take a different view.

The internet has turned millions of people into writers. On Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp and so on, the medium to some extent dictates the message, which is casual, colloquial and nonstandard. The idea that dialect and deviations from ‘correct’ grammar and vocabulary are not ‘wrong’ but deliberate, efficient and possibly even creative is hardly new. All the same, it’s encouraging that McCulloch repeats it. Take lol, for instance. Research reveals a certain sophistication in its use. It occurs only at the beginning or end of an utterance, never both and never in the middle. For example, in ‘got a lot of homework lol’, the addition of lol removes any sense of whining and self-pity; in ‘what are you doing out so late lol’, it makes the message less demanding or reproving. Repeated letters often occur in emotive words: ‘yayyyy’, ‘nooo’. McCulloch thinks it’s brilliant that silent letters are sometimes repeated too, as in ‘dumbbb’, because this creates a ‘form of emotional expression that now has no possible spoken equivalent’.

The way we communicate digitally is growing more complex. A lot of people these days send a string of separate text messages, with no punctuation whatsoever: ‘hey’ (new message) ‘how’s it going’ (new message). The break between one message and another is the equivalent of a row of dots in old-fashioned offline writing, so it’s easy-going, not insistent, and there’s a space in which the other person might reply (but doesn’t). Now, if you write ‘hey.’ it’s a TOTALLY DIFFERENT THING. Full stops are aggressive. As are capital letters.

Then we come to emojis. McCulloch’s idea is that emojis are the internet equivalent of gestures and facial expressions, many of them indeed being pictures of hands or faces. This explains why they got so popular in about five minutes and stayed that way. Millions use emojis every second. Smiley face is the one we all know. Apparently if you’re a teenager and you send a declaration of love to someone heart emoji, heart emoji, heart emoji and they come back smiley face, that’s the worst. It means not interested in a nice way. Well, that gets that over and done with. I’ve sometimes stumbled on the emoji catalogue on my phone. I can’t make head or tail of a lot of them – all those yellow heads with different patches of blue, and the one with heart sunglasses. Does it signify something different to the plain red heart? One ought to know, of course. McCulloch keeps referring to the aubergine emoji (or eggplant, actually), which is apparently rude, but what you’re supposed to do with it I’ve no idea.

by Thomas Blaikie, Literary Review | Read more:

Image: via

Friday, December 6, 2019

Why You Hate Contemporary Architecture

The British author Douglas Adams had this to say about airports: “Airports are ugly. Some are very ugly. Some attain a degree of ugliness that can only be the result of special effort.” Sadly, this truth is not applicable merely to airports: it can also be said of most contemporary architecture.

Take the Tour Montparnasse, a black, slickly glass-panelled skyscraper, looming over the beautiful Paris cityscape like a giant domino waiting to fall. Parisians hated it so much that the city was subsequently forced to enact an ordinance forbidding any further skyscrapers higher than 36 meters.

Or take Boston’s City Hall Plaza. Downtown Boston is generally an attractive place, with old buildings and a waterfront and a beautiful public garden. But Boston’s City Hall is a hideous concrete edifice of mind-bogglingly inscrutable shape, like an ominous component found left over after you’ve painstakingly assembled a complicated household appliance. In the 1960s, before the first batch of concrete had even dried in the mold, people were already begging preemptively for the damn thing to be torn down. There’s a whole additional complex of equally unpleasant federal buildings attached to the same plaza, designed by Walter Gropius, an architect whose chuckle-inducing surname belies the utter cheerlessness of his designs. The John F. Kennedy Building, for example—featurelessly grim on the outside, infuriatingly unnavigable on the inside—is where, among other things, terrified immigrants attend their deportation hearings, and where traumatized veterans come to apply for benefits. Such an inhospitable building sends a very clear message, which is: the government wants its lowly supplicants to feel confused, alienated, and afraid.

The fact is, contemporary architecture gives most regular humans the heebie-jeebies. Try telling that to architects and their acolytes, though, and you’ll get an earful about why your feeling is misguided, the product of some embarrassing misconception about architectural principles. One defense, typically, is that these eyesores are, in reality, incredible feats of engineering. After all, “blobitecture”—which, we regret to say, is a real school of contemporary architecture—is created using complicated computer-driven algorithms! You may think the ensuing blob-structure looks like a tentacled turd, or a crumpled kleenex, but that’s because you don’t have an architect’s trained eye.

The fact is, contemporary architecture gives most regular humans the heebie-jeebies. Try telling that to architects and their acolytes, though, and you’ll get an earful about why your feeling is misguided, the product of some embarrassing misconception about architectural principles. One defense, typically, is that these eyesores are, in reality, incredible feats of engineering. After all, “blobitecture”—which, we regret to say, is a real school of contemporary architecture—is created using complicated computer-driven algorithms! You may think the ensuing blob-structure looks like a tentacled turd, or a crumpled kleenex, but that’s because you don’t have an architect’s trained eye.

Another thing you will often hear from design-school types is that contemporary architecture is honest. It doesn’t rely on the forms and usages of the past, and it is not interested in coddling you and your dumb feelings. Wake up, sheeple! Your boss hates you, and your bloodsucking landlord too, and your government fully intends to grind you between its gears. That’s the world we live in! Get used to it! Fans of Brutalism—the blocky-industrial-concrete school of architecture—are quick to emphasize that these buildings tell it like it is, as if this somehow excused the fact that they look, at best, dreary, and, at worst, like the headquarters of some kind of post-apocalyptic totalitarian dictatorship. (...)

Let’s be really honest with ourselves: a brief glance at any structure designed in the last 50 years should be enough to persuade anyone that something has gone deeply, terribly wrong with us. Some unseen person or force seems committed to replacing literally every attractive and appealing thing with an ugly and unpleasant thing. The architecture produced by contemporary global capitalism is possibly the most obvious visible evidence that it has some kind of perverse effect on the human soul. Of course, there is no accounting for taste, and there may be some among us who are naturally are deeply disposed to appreciate blobs and blocks. But polling suggests that devotees of contemporary architecture are overwhelmingly in the minority: aside from monuments, few of the public’s favorite structures are from the postwar period. (When the results of the poll were released, architects harrumphed that it didn’t “reflect expert judgment” but merely people’s “emotions,” a distinction that rather proves the entire point.) And when it comes to architecture, as distinct from most other forms of art, it isn’t enough to simply shrug and say that personal preferences differ: where public buildings are concerned, or public spaces which have an existing character and historic resonances for the people who live there, to impose an architect’s eccentric will on the masses, and force them to spend their days in spaces they find ugly and unsettling, is actually oppressive and cruel. (...)

There have, after all, been moments in the history of socialism—like the Arts & Crafts movement in late 19th-century England—where the creation of beautiful things was seen as part and parcel of building a fairer, kinder world. A shared egalitarian social undertaking, ideally, ought to be one of joy as well as struggle: in these desperate times, there are certainly more overwhelming imperatives than making the world beautiful to look at, but to decline to make the world more beautiful when it’s in your power to so, or to destroy some beautiful thing without need, is a grotesque perversion of the cooperative ideal. This is especially true when it comes to architecture. The environments we surround ourselves with have the power to shape our thoughts and emotions. People trammeled in on all sides by ugliness are often unhappy without even knowing why. If you live in a place where you are cut off from light, and nature, and color, and regular communion with other humans, it is easy to become desperate, lonely, and depressed. The question is: how did contemporary architecture wind up like this? And how can it be fixed?

For about 2,000 years, everything human beings built was beautiful, or at least unobjectionable. The 20th century put a stop to this, evidenced by the fact that people often go out of their way to vacation in “historic” (read: beautiful) towns that contain as little postwar architecture as possible. But why? What actually changed? Why does there seem to be such an obvious break between the thousands of years before World War II and the postwar period? And why does this seem to hold true everywhere? (...)

This paranoid revulsion against classical aesthetics was not so much a school of thought as a command: from now on, the architect had to be concerned solely with the large-scale form of the structure, not with silly trivialities such as gargoyles and grillwork, no matter how much pleasure such things may have given viewers. It’s somewhat stunning just how uniform the rejection of “ornament” became. Since the eclipse of Art Deco at the end of the 1930s, the intricate designs that characterized centuries of building, across civilizations, from India to Persia to the Mayans, have vanished from architecture. With only a few exceptions, such as New Classical architecture’s mixed successes in reviving Greco-Roman forms, and Postmodern architecture’s irritating attempts to parody them, no modern buildings include the kind of highly complex painting, woodwork, ironwork, and sculpture that characterized the most strikingly beautiful structures of prior eras.

The anti-decorative consensus also accorded with the artistic consensus about what kind of “spirit” 20th century architecture ought to express. The idea of transcendently “beautiful” architecture began to seem faintly ludicrous in a postwar world of chaos, conflict, and alienation. Life was violent, discordant, and uninterpretable. Art should not aspire to futile goals like transcendence, but should try to express the often ugly, brutal, and difficult facts of human beings’ material existence. To call a building “ugly” was therefore no longer an insult: for one thing, the concept of ugliness had no meaning. But to the extent that it did, art could and should be ugly, because life is ugly, and the highest duty of art is to be honest about who we are rather than deluding us with comforting fables.

This idea, that architecture should try to be “honest” rather than “beautiful,” is well expressed in an infamously heated 1982 debate at the Harvard School of Design between two architects, Peter Eisenman and Christopher Alexander. Eisenman is a well-known “starchitect” whose projects are inspired by the deconstructive philosophy of Jacques Derrida, and whose forms are intentionally chaotic and grating. Eisenman took his duty to create “disharmony” seriously: one Eisenman-designed house so departed from the normal concept of a house that its owners actually wrote an entire book about the difficulties they experienced trying to live in it. For example, Eisenman split the master bedroom in two so the couple could not sleep together, installed a precarious staircase without a handrail, and initially refused to include bathrooms. In his violent opposition to the very idea that a real human being might actually attempt to live (and crap, and have sex) in one of his houses, Eisenman recalls the self-important German architect from Evelyn Waugh’s novel Decline and Fall, who becomes exasperated the need to include a staircase between floors: “Why can’t the creatures stay in one place? The problem of architecture is the problem of all art: the elimination of the human element from the consideration of form. The only perfect building must be the factory, because that is built to house machines, not men.”

Alexander, by contrast, is one of the few major figures in architecture who believes that an objective standard of beauty is an important value for the profession; his buildings, which are often small-scale projects like gardens or schoolyards or homes, attempt to be warm and comfortable, and often employ traditional—what he calls “timeless”—design practices. In the debate, Alexander lambasted Eisenman for wanting buildings that are “prickly and strange,” and defended a conception of architecture that prioritizes human feeling and emotion. Eisenman, evidently trying his damnedest to behave like a cartoon parody of a pretentious artist, declared that he found the Chartres cathedral too boring to visit even once: “in fact,” he stated, “I have gone to Chartres a number of times to eat in the restaurant across the street — had a 1934 red Mersault wine, which was exquisite — I never went into the cathedral. The cathedral was done en passant. Once you’ve seen one Gothic cathedral, you have seen them all.” Alexander replied: “I find that incomprehensible. I find it very irresponsible. I find it nutty. I feel sorry for the man. I also feel incredibly angry because he is fucking up the world.”

Take the Tour Montparnasse, a black, slickly glass-panelled skyscraper, looming over the beautiful Paris cityscape like a giant domino waiting to fall. Parisians hated it so much that the city was subsequently forced to enact an ordinance forbidding any further skyscrapers higher than 36 meters.

Or take Boston’s City Hall Plaza. Downtown Boston is generally an attractive place, with old buildings and a waterfront and a beautiful public garden. But Boston’s City Hall is a hideous concrete edifice of mind-bogglingly inscrutable shape, like an ominous component found left over after you’ve painstakingly assembled a complicated household appliance. In the 1960s, before the first batch of concrete had even dried in the mold, people were already begging preemptively for the damn thing to be torn down. There’s a whole additional complex of equally unpleasant federal buildings attached to the same plaza, designed by Walter Gropius, an architect whose chuckle-inducing surname belies the utter cheerlessness of his designs. The John F. Kennedy Building, for example—featurelessly grim on the outside, infuriatingly unnavigable on the inside—is where, among other things, terrified immigrants attend their deportation hearings, and where traumatized veterans come to apply for benefits. Such an inhospitable building sends a very clear message, which is: the government wants its lowly supplicants to feel confused, alienated, and afraid.

The fact is, contemporary architecture gives most regular humans the heebie-jeebies. Try telling that to architects and their acolytes, though, and you’ll get an earful about why your feeling is misguided, the product of some embarrassing misconception about architectural principles. One defense, typically, is that these eyesores are, in reality, incredible feats of engineering. After all, “blobitecture”—which, we regret to say, is a real school of contemporary architecture—is created using complicated computer-driven algorithms! You may think the ensuing blob-structure looks like a tentacled turd, or a crumpled kleenex, but that’s because you don’t have an architect’s trained eye.

The fact is, contemporary architecture gives most regular humans the heebie-jeebies. Try telling that to architects and their acolytes, though, and you’ll get an earful about why your feeling is misguided, the product of some embarrassing misconception about architectural principles. One defense, typically, is that these eyesores are, in reality, incredible feats of engineering. After all, “blobitecture”—which, we regret to say, is a real school of contemporary architecture—is created using complicated computer-driven algorithms! You may think the ensuing blob-structure looks like a tentacled turd, or a crumpled kleenex, but that’s because you don’t have an architect’s trained eye. Another thing you will often hear from design-school types is that contemporary architecture is honest. It doesn’t rely on the forms and usages of the past, and it is not interested in coddling you and your dumb feelings. Wake up, sheeple! Your boss hates you, and your bloodsucking landlord too, and your government fully intends to grind you between its gears. That’s the world we live in! Get used to it! Fans of Brutalism—the blocky-industrial-concrete school of architecture—are quick to emphasize that these buildings tell it like it is, as if this somehow excused the fact that they look, at best, dreary, and, at worst, like the headquarters of some kind of post-apocalyptic totalitarian dictatorship. (...)

Let’s be really honest with ourselves: a brief glance at any structure designed in the last 50 years should be enough to persuade anyone that something has gone deeply, terribly wrong with us. Some unseen person or force seems committed to replacing literally every attractive and appealing thing with an ugly and unpleasant thing. The architecture produced by contemporary global capitalism is possibly the most obvious visible evidence that it has some kind of perverse effect on the human soul. Of course, there is no accounting for taste, and there may be some among us who are naturally are deeply disposed to appreciate blobs and blocks. But polling suggests that devotees of contemporary architecture are overwhelmingly in the minority: aside from monuments, few of the public’s favorite structures are from the postwar period. (When the results of the poll were released, architects harrumphed that it didn’t “reflect expert judgment” but merely people’s “emotions,” a distinction that rather proves the entire point.) And when it comes to architecture, as distinct from most other forms of art, it isn’t enough to simply shrug and say that personal preferences differ: where public buildings are concerned, or public spaces which have an existing character and historic resonances for the people who live there, to impose an architect’s eccentric will on the masses, and force them to spend their days in spaces they find ugly and unsettling, is actually oppressive and cruel. (...)

There have, after all, been moments in the history of socialism—like the Arts & Crafts movement in late 19th-century England—where the creation of beautiful things was seen as part and parcel of building a fairer, kinder world. A shared egalitarian social undertaking, ideally, ought to be one of joy as well as struggle: in these desperate times, there are certainly more overwhelming imperatives than making the world beautiful to look at, but to decline to make the world more beautiful when it’s in your power to so, or to destroy some beautiful thing without need, is a grotesque perversion of the cooperative ideal. This is especially true when it comes to architecture. The environments we surround ourselves with have the power to shape our thoughts and emotions. People trammeled in on all sides by ugliness are often unhappy without even knowing why. If you live in a place where you are cut off from light, and nature, and color, and regular communion with other humans, it is easy to become desperate, lonely, and depressed. The question is: how did contemporary architecture wind up like this? And how can it be fixed?

For about 2,000 years, everything human beings built was beautiful, or at least unobjectionable. The 20th century put a stop to this, evidenced by the fact that people often go out of their way to vacation in “historic” (read: beautiful) towns that contain as little postwar architecture as possible. But why? What actually changed? Why does there seem to be such an obvious break between the thousands of years before World War II and the postwar period? And why does this seem to hold true everywhere? (...)

This paranoid revulsion against classical aesthetics was not so much a school of thought as a command: from now on, the architect had to be concerned solely with the large-scale form of the structure, not with silly trivialities such as gargoyles and grillwork, no matter how much pleasure such things may have given viewers. It’s somewhat stunning just how uniform the rejection of “ornament” became. Since the eclipse of Art Deco at the end of the 1930s, the intricate designs that characterized centuries of building, across civilizations, from India to Persia to the Mayans, have vanished from architecture. With only a few exceptions, such as New Classical architecture’s mixed successes in reviving Greco-Roman forms, and Postmodern architecture’s irritating attempts to parody them, no modern buildings include the kind of highly complex painting, woodwork, ironwork, and sculpture that characterized the most strikingly beautiful structures of prior eras.

This idea, that architecture should try to be “honest” rather than “beautiful,” is well expressed in an infamously heated 1982 debate at the Harvard School of Design between two architects, Peter Eisenman and Christopher Alexander. Eisenman is a well-known “starchitect” whose projects are inspired by the deconstructive philosophy of Jacques Derrida, and whose forms are intentionally chaotic and grating. Eisenman took his duty to create “disharmony” seriously: one Eisenman-designed house so departed from the normal concept of a house that its owners actually wrote an entire book about the difficulties they experienced trying to live in it. For example, Eisenman split the master bedroom in two so the couple could not sleep together, installed a precarious staircase without a handrail, and initially refused to include bathrooms. In his violent opposition to the very idea that a real human being might actually attempt to live (and crap, and have sex) in one of his houses, Eisenman recalls the self-important German architect from Evelyn Waugh’s novel Decline and Fall, who becomes exasperated the need to include a staircase between floors: “Why can’t the creatures stay in one place? The problem of architecture is the problem of all art: the elimination of the human element from the consideration of form. The only perfect building must be the factory, because that is built to house machines, not men.”

Alexander, by contrast, is one of the few major figures in architecture who believes that an objective standard of beauty is an important value for the profession; his buildings, which are often small-scale projects like gardens or schoolyards or homes, attempt to be warm and comfortable, and often employ traditional—what he calls “timeless”—design practices. In the debate, Alexander lambasted Eisenman for wanting buildings that are “prickly and strange,” and defended a conception of architecture that prioritizes human feeling and emotion. Eisenman, evidently trying his damnedest to behave like a cartoon parody of a pretentious artist, declared that he found the Chartres cathedral too boring to visit even once: “in fact,” he stated, “I have gone to Chartres a number of times to eat in the restaurant across the street — had a 1934 red Mersault wine, which was exquisite — I never went into the cathedral. The cathedral was done en passant. Once you’ve seen one Gothic cathedral, you have seen them all.” Alexander replied: “I find that incomprehensible. I find it very irresponsible. I find it nutty. I feel sorry for the man. I also feel incredibly angry because he is fucking up the world.”

by Nathan J. Robinson, Current Affairs | Read more:

Image: uncredited

Atomic Gardening

Atomic gardening is a form of mutation breeding where plants are exposed to radioactive sources, typically cobalt-60, in order to generate mutations, some of which have turned out to be useful.

The practice of plant irradiation has resulted in the development of over 2000 new varieties of plants, most of which are now used in agricultural production. One example is the resistance to verticillium wilt of the "Todd's Mitcham" cultivar of peppermint which was produced from a breeding and test program at Brookhaven National Laboratory from the mid-1950s. Additionally, the Rio Star Grapefruit, developed at the Texas A&M Citrus Center in the 1970s, now accounts for over three quarters of the grapefruit produced in Texas. (...)

Despite the initial enthusiasm, the Atomic Gardening Society declined by the mid 1960s. This was due to a combination of a shifting political climate away from atomic energy and a failure on the part of the crowd sourced Society to produce noteworthy results. In spite of this, large-scale gamma gardens remained in use, and a number of commercial plant varieties were developed and released by laboratories and private companies alike.

Despite the initial enthusiasm, the Atomic Gardening Society declined by the mid 1960s. This was due to a combination of a shifting political climate away from atomic energy and a failure on the part of the crowd sourced Society to produce noteworthy results. In spite of this, large-scale gamma gardens remained in use, and a number of commercial plant varieties were developed and released by laboratories and private companies alike.

Gamma gardens were typically five acres in size, and were arranged in a circular pattern with a retractable radiation source in the middle. Plants were usually laid out like slices of a pie, stemming from the central radiation source; this pattern produced a range of radiation doses over the radius from the center. Radioactive bombardment would take place for around twenty hours, after which scientists wearing protective equipment would enter the garden and assess the results. The plants nearest the center usually died, while the ones further out often featured "tumors and other growth abnormalities". Beyond these were the plants of interest, with a higher than usual range of mutations, though not to the damaging extent of those closer to the radiation source. These gamma gardens have continued to operate on largely the same designs as those conceived in the 1950s.

The practice of plant irradiation has resulted in the development of over 2000 new varieties of plants, most of which are now used in agricultural production. One example is the resistance to verticillium wilt of the "Todd's Mitcham" cultivar of peppermint which was produced from a breeding and test program at Brookhaven National Laboratory from the mid-1950s. Additionally, the Rio Star Grapefruit, developed at the Texas A&M Citrus Center in the 1970s, now accounts for over three quarters of the grapefruit produced in Texas. (...)

Despite the initial enthusiasm, the Atomic Gardening Society declined by the mid 1960s. This was due to a combination of a shifting political climate away from atomic energy and a failure on the part of the crowd sourced Society to produce noteworthy results. In spite of this, large-scale gamma gardens remained in use, and a number of commercial plant varieties were developed and released by laboratories and private companies alike.

Despite the initial enthusiasm, the Atomic Gardening Society declined by the mid 1960s. This was due to a combination of a shifting political climate away from atomic energy and a failure on the part of the crowd sourced Society to produce noteworthy results. In spite of this, large-scale gamma gardens remained in use, and a number of commercial plant varieties were developed and released by laboratories and private companies alike.Gamma gardens were typically five acres in size, and were arranged in a circular pattern with a retractable radiation source in the middle. Plants were usually laid out like slices of a pie, stemming from the central radiation source; this pattern produced a range of radiation doses over the radius from the center. Radioactive bombardment would take place for around twenty hours, after which scientists wearing protective equipment would enter the garden and assess the results. The plants nearest the center usually died, while the ones further out often featured "tumors and other growth abnormalities". Beyond these were the plants of interest, with a higher than usual range of mutations, though not to the damaging extent of those closer to the radiation source. These gamma gardens have continued to operate on largely the same designs as those conceived in the 1950s.

by Wikipedia | Read more:

Image: uncredited

[ed. "Ruby-red grapefruit, rice, wheat, pears, cotton, peas, sunflowers, bananas and countless other produce owe their present-day heartiness to the genetic modification afforded by atomic gardening." See also: Atomic gardening in the 1950s (Ripley's).]

[ed. "Ruby-red grapefruit, rice, wheat, pears, cotton, peas, sunflowers, bananas and countless other produce owe their present-day heartiness to the genetic modification afforded by atomic gardening." See also: Atomic gardening in the 1950s (Ripley's).]

ICE Creates Fake University in Michigan

A total of about 250 students have now been arrested since January on immigration violations by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) as part of a sting operation by federal agents who enticed foreign-born students, mostly from India, to attend the school that marketed itself as offering graduate programs in technology and computer studies, according to ICE officials.

Many of those arrested have been deported to India while others are contesting their removals. One has been allowed to stay after being granted lawful permanent resident status by an immigration judge.

The students had arrived legally in the U.S. on student visas, but since the University of Farmington was later revealed to be a creation of federal agents, they lost their immigration status after it was shut down in January. The school was located on Northwestern Highway near 13 Mile Road in Farmington Hills and staffed with undercover agents posing as university officials. (...)

The students had arrived legally in the U.S. on student visas, but since the University of Farmington was later revealed to be a creation of federal agents, they lost their immigration status after it was shut down in January. The school was located on Northwestern Highway near 13 Mile Road in Farmington Hills and staffed with undercover agents posing as university officials. (...)

Attorneys for the students arrested said they were unfairly trapped by the U.S. government since the Department of Homeland Security had said on its website that the university was legitimate. An accreditation agency that was working with the U.S. on its sting operation also listed the university as legitimate.

There were more than 600 students enrolled at the university, which was created a few years ago by federal law enforcement officials with ICE. Records filed with the state Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (LARA) show that the University of Farmington was incorporated in January 2016.

Many of the students had enrolled with the university through a program known as Curricular Practical Training (CPT), which allows students to work in the U.S through a F-1 visa program for foreign students. Some had transferred to the University of Farmington from other schools that had lost accreditation, which means they would no longer be in immigration status and allowed to remain in the U.S.

Emails obtained by the Free Press earlier this year showed how the fake university attracted students to the university, which cost about $12,000 on average in tuition and fees per year.

The U.S. "trapped the vulnerable people who just wanted to maintain (legal immigration) status," Rahul Reddy, a Texas attorney who represented or advised some of the students arrested, told the Free Press this week. "They preyed upon on them."

The fake university is believed to have collected millions of dollars from the unsuspecting students. An email from the university's president, named Ali Milani, told students that graduate programs' tuition is $2,500 per quarter and the average cost is $1,000 per month.

"They made a lot of money," Reddy said of the U.S. government. (...)

Attorneys for ICE and the Department of Justice maintain that the students should have known it was not a legitimate university because it did not have classes in a physical location. Some CPT programs have classes combined with work programs at companies.

"Their true intent could not be clearer," Assistant U.S. Attorney Brandon Helms wrote in a sentencing memo this month for Rampeesa, one of the eight recruiters, of the hundreds of students enrolled. "While 'enrolled' at the University, one hundred percent of the foreign citizen students never spent a single second in a classroom. If it were truly about obtaining an education, the University would not have been able to attract anyone, because it had no teachers, classes, or educational services." (...)

Reddy said, though, that in some cases, students who transferred out from the University of Farmington after realizing they didn't have classes on-site, were still arrested.

by Niraj Warikoo, Detroit Free Press | Read more:

Image: Eric Seals, Detroit Free Press

[ed. Your tax dollars at work.]

Many of those arrested have been deported to India while others are contesting their removals. One has been allowed to stay after being granted lawful permanent resident status by an immigration judge.

The students had arrived legally in the U.S. on student visas, but since the University of Farmington was later revealed to be a creation of federal agents, they lost their immigration status after it was shut down in January. The school was located on Northwestern Highway near 13 Mile Road in Farmington Hills and staffed with undercover agents posing as university officials. (...)

The students had arrived legally in the U.S. on student visas, but since the University of Farmington was later revealed to be a creation of federal agents, they lost their immigration status after it was shut down in January. The school was located on Northwestern Highway near 13 Mile Road in Farmington Hills and staffed with undercover agents posing as university officials. (...)Attorneys for the students arrested said they were unfairly trapped by the U.S. government since the Department of Homeland Security had said on its website that the university was legitimate. An accreditation agency that was working with the U.S. on its sting operation also listed the university as legitimate.

There were more than 600 students enrolled at the university, which was created a few years ago by federal law enforcement officials with ICE. Records filed with the state Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (LARA) show that the University of Farmington was incorporated in January 2016.

Many of the students had enrolled with the university through a program known as Curricular Practical Training (CPT), which allows students to work in the U.S through a F-1 visa program for foreign students. Some had transferred to the University of Farmington from other schools that had lost accreditation, which means they would no longer be in immigration status and allowed to remain in the U.S.

Emails obtained by the Free Press earlier this year showed how the fake university attracted students to the university, which cost about $12,000 on average in tuition and fees per year.

The U.S. "trapped the vulnerable people who just wanted to maintain (legal immigration) status," Rahul Reddy, a Texas attorney who represented or advised some of the students arrested, told the Free Press this week. "They preyed upon on them."

The fake university is believed to have collected millions of dollars from the unsuspecting students. An email from the university's president, named Ali Milani, told students that graduate programs' tuition is $2,500 per quarter and the average cost is $1,000 per month.

"They made a lot of money," Reddy said of the U.S. government. (...)

Attorneys for ICE and the Department of Justice maintain that the students should have known it was not a legitimate university because it did not have classes in a physical location. Some CPT programs have classes combined with work programs at companies.

"Their true intent could not be clearer," Assistant U.S. Attorney Brandon Helms wrote in a sentencing memo this month for Rampeesa, one of the eight recruiters, of the hundreds of students enrolled. "While 'enrolled' at the University, one hundred percent of the foreign citizen students never spent a single second in a classroom. If it were truly about obtaining an education, the University would not have been able to attract anyone, because it had no teachers, classes, or educational services." (...)

Reddy said, though, that in some cases, students who transferred out from the University of Farmington after realizing they didn't have classes on-site, were still arrested.

by Niraj Warikoo, Detroit Free Press | Read more:

Image: Eric Seals, Detroit Free Press

[ed. Your tax dollars at work.]

Hippie Inc: How the Counterculture Went Corporate

Brian is telling a young Asian-American woman about the five-day workshop he’s here to attend. “It’s called ‘Bio-hacking the Language of Intimacy’,” he says. “Uh-huh,” says the Asian-American woman. She directs this less at Brian than at the kelp forest floating offshore. Brian presses on. What he particularly appreciates is the ability to talk about stuff he can’t talk about at work. Relationships and so forth. “You know,” he says, “really make that human connection.”

The Asian-American woman gives him the sort of bright, dead-eyed smile Californians deploy when they’re about to violently disagree with you. “I find I can make human connections in lots of different contexts.”

Brian goes quiet. In all but one sense it’s a typically, even touchingly American courtship ritual: the clean-cut young man, no less diffident nor deferential than his grandfather might have been; the young woman off-handedly wielding her power over him, yet to be impressed. The crucial difference is that both parties are naked – not only naked, in the woman’s case, but standing up in the water, exposing herself in full-frontal immodesty to Brian and the cool Pacific breezes.

We are in the outdoor sulphur springs that cling to the cliffside at the Esalen Institute, a spiritual retreat centre in Big Sur, California. Here naked sharing is commonplace and as sapped of erotic charge as it would be in a naturist campsite – which is just as well, as I’m naked too, the gooseberry in the hot tub, desperately aiming for an air of easygoing self-composure as I try not to look at Brian’s thighs.

We are in the outdoor sulphur springs that cling to the cliffside at the Esalen Institute, a spiritual retreat centre in Big Sur, California. Here naked sharing is commonplace and as sapped of erotic charge as it would be in a naturist campsite – which is just as well, as I’m naked too, the gooseberry in the hot tub, desperately aiming for an air of easygoing self-composure as I try not to look at Brian’s thighs.