“... it's a beautiful day, the beaches are open and people are having a wonderful time.”

Image: Jaws

At eight-forty-five on a recent Monday morning, fifteen minutes before Costco’s official opening time, the crowd waiting to get inside the warehouse in Brooklyn was already about a hundred strong. Bodies and carts were jammed together inside the store’s open vestibule, pressing up against the still-locked doors; outside, spilling into the parking lot and blocking the flow of traffic, nearly twice as many shoppers fanned out around the vestibule entrances, aiming their carts with the tense energy of bobsledders waiting for the starting gun. An employee pushing a pallet cart shouted for people to get off the asphalt and instead wrap around the building, which everyone ignored, so instead he called out to a co-worker standing closer to the front of the throng: “Tell them they’ve got to open the doors early!” The second employee snaked his way through the crowd to the doors. As he turned sideways to fit between two logjammed carts, he muttered, “This is a madhouse.”

At eight-forty-five on a recent Monday morning, fifteen minutes before Costco’s official opening time, the crowd waiting to get inside the warehouse in Brooklyn was already about a hundred strong. Bodies and carts were jammed together inside the store’s open vestibule, pressing up against the still-locked doors; outside, spilling into the parking lot and blocking the flow of traffic, nearly twice as many shoppers fanned out around the vestibule entrances, aiming their carts with the tense energy of bobsledders waiting for the starting gun. An employee pushing a pallet cart shouted for people to get off the asphalt and instead wrap around the building, which everyone ignored, so instead he called out to a co-worker standing closer to the front of the throng: “Tell them they’ve got to open the doors early!” The second employee snaked his way through the crowd to the doors. As he turned sideways to fit between two logjammed carts, he muttered, “This is a madhouse.” More than Yeats, however, it’s Joan Didion who deserves credit for this endlessly recycled trope about an uncentered center. Didion’s 1968 essay collection, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” borrowing another phrase from the same poem, is a cultural landmark much beloved by the sorts of people who write opinion pieces and headlines. (“Bare Ruined Choir” is a book title stolen from another poet, Shakespeare, by another journalist who gained fame in the 1960s, Garry Wills.) (...)

More than Yeats, however, it’s Joan Didion who deserves credit for this endlessly recycled trope about an uncentered center. Didion’s 1968 essay collection, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” borrowing another phrase from the same poem, is a cultural landmark much beloved by the sorts of people who write opinion pieces and headlines. (“Bare Ruined Choir” is a book title stolen from another poet, Shakespeare, by another journalist who gained fame in the 1960s, Garry Wills.) (...)Pretty little 16-year-old middle-class chick comes to the Haight to see what it’s all about & gets picked up by a 17-year-old dealer who spends all day shooting her full of speed again & again, then feeds her 3,000 mikes & raffles off her temporarily unemployed body for the biggest Haight Street gangbang since the night before last. The politics and ethics of ecstasy.Didion provides no context for the violence, no judgment on the horror. It’s just an event that occurred in a particular time and place — Haight Ashbury, year of the Summer of Love.

The impact on the country’s tourism industry has been brutal, prompting panicked representatives to warn that a “generalized panic” over coronavirus could “sink” the sector. “There is a risk that Italy will drop off the international tourism map altogether,” said Carlo Sangalli, president of Milan’s Chamber of Commerce. “The wave of contagions over the past week is causing huge financial losses that will be difficult to recoup.”

The impact on the country’s tourism industry has been brutal, prompting panicked representatives to warn that a “generalized panic” over coronavirus could “sink” the sector. “There is a risk that Italy will drop off the international tourism map altogether,” said Carlo Sangalli, president of Milan’s Chamber of Commerce. “The wave of contagions over the past week is causing huge financial losses that will be difficult to recoup.” Next door to LensCrafters, there’s a shop that sells gemstones, crystals, sage, and pink Himalayan salt lamps. The burning sage makes that end of the mall smell musky, animalistic—a strangely feral odor in this synthetic environment. Snaking its lazy way around the scuffed tile floor is an automated miniature train, the sort children might ride at the zoo, driven by an adult man dressed as a conductor; it toots loudly and gratingly at regular intervals. JCPenney and Macy’s and Dillard’s closed months and years ago, while Sears is limping along in its fire-sale days. At Foot Locker, I try on black-and-white Vans in an M. C. Escher print. At Hot Topic, I browse the cheap T-shirts printed with sayings like Keep Calm and Drink On and Practice Safe Hex. I eat a corn dog, fried and delicious, at a place called Hot Dog on a Stick. (I really do.) The atmosphere is depressing, in all its forced cheerfulness and precise evocation of the empty material promises of my ’80s-era youth.

Next door to LensCrafters, there’s a shop that sells gemstones, crystals, sage, and pink Himalayan salt lamps. The burning sage makes that end of the mall smell musky, animalistic—a strangely feral odor in this synthetic environment. Snaking its lazy way around the scuffed tile floor is an automated miniature train, the sort children might ride at the zoo, driven by an adult man dressed as a conductor; it toots loudly and gratingly at regular intervals. JCPenney and Macy’s and Dillard’s closed months and years ago, while Sears is limping along in its fire-sale days. At Foot Locker, I try on black-and-white Vans in an M. C. Escher print. At Hot Topic, I browse the cheap T-shirts printed with sayings like Keep Calm and Drink On and Practice Safe Hex. I eat a corn dog, fried and delicious, at a place called Hot Dog on a Stick. (I really do.) The atmosphere is depressing, in all its forced cheerfulness and precise evocation of the empty material promises of my ’80s-era youth. For several of the contributors, the most prominent thread that runs through the book is love – both the love dogs have for people and the love that people return. Our love of dogs is in part a response to their happiness but also, as the legendary French actor and animal welfare activist Brigitte Bardot observes, to their wanting us to be happy. Our love, in effect, responds to their love. “Response”, perhaps, is not the ideal word. Certainly, love for a dog need not be an unconsidered, mechanical reaction to their affection. As Monty Don pointed out in his book on his golden retriever Nigel, a dog is an “opportunity” for a person to develop, shape and manifest love for a being that is not going to reject or betray this love. In a fine essay in the anthology, the late Roger Scruton argues that while dogs may rightly invite love, it must be of the right kind. Although dogs have been “raised to the edge of personhood”, they are not persons, and to ignore this will damage dog and owner alike. The owner will have unreasonable expectations that the dog is bound to disappoint, or a dog may suffer longer than necessary when an owner, viewing the pet as a person, refuses to have it euthanized.

For several of the contributors, the most prominent thread that runs through the book is love – both the love dogs have for people and the love that people return. Our love of dogs is in part a response to their happiness but also, as the legendary French actor and animal welfare activist Brigitte Bardot observes, to their wanting us to be happy. Our love, in effect, responds to their love. “Response”, perhaps, is not the ideal word. Certainly, love for a dog need not be an unconsidered, mechanical reaction to their affection. As Monty Don pointed out in his book on his golden retriever Nigel, a dog is an “opportunity” for a person to develop, shape and manifest love for a being that is not going to reject or betray this love. In a fine essay in the anthology, the late Roger Scruton argues that while dogs may rightly invite love, it must be of the right kind. Although dogs have been “raised to the edge of personhood”, they are not persons, and to ignore this will damage dog and owner alike. The owner will have unreasonable expectations that the dog is bound to disappoint, or a dog may suffer longer than necessary when an owner, viewing the pet as a person, refuses to have it euthanized. If our love is a response to the dog’s, so, in turn, is the dog’s love a response to ours. It is not true, as Ullman maintains, echoing the popular view, that dogs “offer unconditional love and loyalty, no matter how badly we behave”. It is possible, indeed horribly frequent, for people to forfeit a dog’s love. Those dull-eyed, mangy and broken animals whose owners chain them up and ignore them no longer love these people. It is true that dogs do not impose conditions on us, but this, as Scruton explains, is because they cannot do so, not because they generously refrain from doing so. For a similar reason, it is questionable for Alice Walker to praise her labrador, Marley, for “how swiftly she forgives me”. Marley neither forgives nor blames, for these are actions that presuppose a range of concepts – responsibility, intention, negligence and so on – that are not in her or any other dog’s repertoire. A term better than “unconditional” for characterizing a dog’s love might be “uncomplicated” or “unreflecting”, neither of which is intended to detract from what Lorenz called the “immeasurability” of this love.

If our love is a response to the dog’s, so, in turn, is the dog’s love a response to ours. It is not true, as Ullman maintains, echoing the popular view, that dogs “offer unconditional love and loyalty, no matter how badly we behave”. It is possible, indeed horribly frequent, for people to forfeit a dog’s love. Those dull-eyed, mangy and broken animals whose owners chain them up and ignore them no longer love these people. It is true that dogs do not impose conditions on us, but this, as Scruton explains, is because they cannot do so, not because they generously refrain from doing so. For a similar reason, it is questionable for Alice Walker to praise her labrador, Marley, for “how swiftly she forgives me”. Marley neither forgives nor blames, for these are actions that presuppose a range of concepts – responsibility, intention, negligence and so on – that are not in her or any other dog’s repertoire. A term better than “unconditional” for characterizing a dog’s love might be “uncomplicated” or “unreflecting”, neither of which is intended to detract from what Lorenz called the “immeasurability” of this love. What are the reasons for this institutional breakdown? It’s tempting to blame politics – President Donald Trump is obviously mainly concerned with the health of the stock market, and conservative media outlets have worked to downplay the threat. But the failures of the U.S.’ coronavirus response happened far too quickly to lay most of the blame at the feet of the administration. Instead, it points to long-term decay in the quality of the country’s bureaucracy.

What are the reasons for this institutional breakdown? It’s tempting to blame politics – President Donald Trump is obviously mainly concerned with the health of the stock market, and conservative media outlets have worked to downplay the threat. But the failures of the U.S.’ coronavirus response happened far too quickly to lay most of the blame at the feet of the administration. Instead, it points to long-term decay in the quality of the country’s bureaucracy. The campaigns of those who deviate from the traditional model of the American president—the campaign of anyone who is not white and Christian and male—will always carry more than their share of weight. But Warren had something about her, apparently: something that galled the pundits and the public in a way that led to assessments of her not just as “strident” and “shrill,” but also as “condescending.” The matter is not merely that the candidate is unlikable, these deployments of condescending imply. The matter is instead that her unlikability has a specific source, beyond bias and internalized misogyny. Warren knows a lot, and has accomplished a lot, and is extremely competent, condescending acknowledges, before twisting the knife: It is precisely because of those achievements that she represents a threat. Condescending attempts to rationalize an irrational prejudice. It suggests the lurchings of a zero-sum world—a physics in which the achievements of one person are insulting to everyone else. When I hear her talk, I want to slap her, even when I agree with her.

The campaigns of those who deviate from the traditional model of the American president—the campaign of anyone who is not white and Christian and male—will always carry more than their share of weight. But Warren had something about her, apparently: something that galled the pundits and the public in a way that led to assessments of her not just as “strident” and “shrill,” but also as “condescending.” The matter is not merely that the candidate is unlikable, these deployments of condescending imply. The matter is instead that her unlikability has a specific source, beyond bias and internalized misogyny. Warren knows a lot, and has accomplished a lot, and is extremely competent, condescending acknowledges, before twisting the knife: It is precisely because of those achievements that she represents a threat. Condescending attempts to rationalize an irrational prejudice. It suggests the lurchings of a zero-sum world—a physics in which the achievements of one person are insulting to everyone else. When I hear her talk, I want to slap her, even when I agree with her. In November of last year, I opened a brokerage account. I had been reading simple, bullet-pointed introductions to financial literacy for a few months before that, manuals “for dummies” of the sort that I am conditioned to hold in contempt when their subject is, say, Latin, or the Protestant Reformation. After this period of study, I determined I was ready to invest the bulk of the money I had to my name, around $150,000, in the stock market (an amount large enough to make me already worthy of the guillotine, for some who have nothing, and small enough to burn or to lose with no consequences, for some who have much more). The fact that I had that amount of money in the first place was largely a bureaucratic mistake. When I quit my job at a university in Canada after nine years of working there, the human-resources people closed my retirement account and sent me the full amount in a single check. That check—the “retirement” I unwittingly took with severe early-withdrawal penalties at the age of forty-one when in fact I was only moving to a job in another country—plus some of the money I had saved over just the past few years from book-contract advances, was to be the seed funding for what I hoped, and still hope, might grow into something much larger through the alchemy of capital gains.

In November of last year, I opened a brokerage account. I had been reading simple, bullet-pointed introductions to financial literacy for a few months before that, manuals “for dummies” of the sort that I am conditioned to hold in contempt when their subject is, say, Latin, or the Protestant Reformation. After this period of study, I determined I was ready to invest the bulk of the money I had to my name, around $150,000, in the stock market (an amount large enough to make me already worthy of the guillotine, for some who have nothing, and small enough to burn or to lose with no consequences, for some who have much more). The fact that I had that amount of money in the first place was largely a bureaucratic mistake. When I quit my job at a university in Canada after nine years of working there, the human-resources people closed my retirement account and sent me the full amount in a single check. That check—the “retirement” I unwittingly took with severe early-withdrawal penalties at the age of forty-one when in fact I was only moving to a job in another country—plus some of the money I had saved over just the past few years from book-contract advances, was to be the seed funding for what I hoped, and still hope, might grow into something much larger through the alchemy of capital gains. The current divide is not about one war. It is about capitalism—whether it can be reformed and remade to create the kind of broad prosperity the country once knew, but without the sexism and racism of the postwar period, as liberals hope; or whether corporate power is now so great that we are simply beyond that, as the younger socialists would argue, and more radical surgery is called for. Further, it’s about who holds power in the Democratic Party, and the real and perceived ways in which the Democrats of the last thirty years or so have failed to challenge that power. These questions are not easily resolved, so this internal conflict is likely to last for some time and grow very bitter indeed. If Sanders wins the nomination, he will presumably try to unify the party behind his movement—but many in the party establishment will be reluctant to join, and a substantial number of his most fervent supporters wouldn’t welcome them anyway. It does not seem to me too alarmist to wonder if the Democrats can survive all this; if 2020 will be to the Democrats as 1852 was to the Whigs—a schismatic turning point that proved that the divisions were beyond bridging.

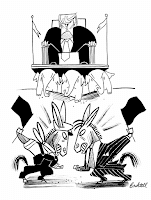

The current divide is not about one war. It is about capitalism—whether it can be reformed and remade to create the kind of broad prosperity the country once knew, but without the sexism and racism of the postwar period, as liberals hope; or whether corporate power is now so great that we are simply beyond that, as the younger socialists would argue, and more radical surgery is called for. Further, it’s about who holds power in the Democratic Party, and the real and perceived ways in which the Democrats of the last thirty years or so have failed to challenge that power. These questions are not easily resolved, so this internal conflict is likely to last for some time and grow very bitter indeed. If Sanders wins the nomination, he will presumably try to unify the party behind his movement—but many in the party establishment will be reluctant to join, and a substantial number of his most fervent supporters wouldn’t welcome them anyway. It does not seem to me too alarmist to wonder if the Democrats can survive all this; if 2020 will be to the Democrats as 1852 was to the Whigs—a schismatic turning point that proved that the divisions were beyond bridging. But shortly after the birth of Ellingwood’s second son, in June 2010, his marriage fell apart. He and his wife each sued for sole custody. To pay his lawyer, he planned to refinance his house, and his grandfather advanced him his inheritance. By 2012, Ellingwood had paid his lawyer more than $80,000, and in the chaos of fighting for his children, he stopped making his mortgage payments. He consulted with several professionals, who urged him to file for bankruptcy protection so that he could get an automatic stay preventing the sale of his house.

But shortly after the birth of Ellingwood’s second son, in June 2010, his marriage fell apart. He and his wife each sued for sole custody. To pay his lawyer, he planned to refinance his house, and his grandfather advanced him his inheritance. By 2012, Ellingwood had paid his lawyer more than $80,000, and in the chaos of fighting for his children, he stopped making his mortgage payments. He consulted with several professionals, who urged him to file for bankruptcy protection so that he could get an automatic stay preventing the sale of his house.