Sunday, December 10, 2023

Saturday, December 9, 2023

Was It Worth It, Kevin?

And now, the end is near

And so I face the final curtain.

Come on! You know the Sinatra classic. Croon along with me as we emotionally gird ourselves for the closing act of Kevin McCarthy’s long, disappointing stint in Congress.

Having spent most of 2023 as a punching bag for his conference’s right flank, Mr. McCarthy has finally reached his pain threshold. At the end of this month, he announced on Wednesday, he will pack up his toys and flee the House, having made history as the first speaker booted from the job.

But do not cry for the former young gun. He has too few regrets to mention. As he bravely cheered his own performance in a Wall Street Journal essay announcing his departure, “I go knowing I left it all on the field — as always, with a smile on my face.”

Boy, did he. In his fevered pursuit of the gavel, Mr. McCarthy time and again prostrated himself before the altar of Donald Trump, sacrificing basically all the things that matter: his dignity, his integrity, his values (such as they were), his soul — you name it.

Now, looking back on each and every highway the congressman traveled to reach this point, I feel compelled to ask: Was it worth it, Kev?

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Mr. McCarthy came roaring into Washington from California in 2007 with big dreams and enormous promise. Alongside Paul Ryan and Eric Cantor, he was part of a new generation of fresh, feisty conservatives looking to overhaul what they saw as a stale, out-of-touch Republican Party.

Like an adorable boy band, the three pals each had a persona: Mr. Ryan, the policy wonk; Mr. Cantor, the blossoming leader; and Mr. McCarthy, the political animal. Mr. McCarthy was less concerned about policy or ideology than about mapping out the wins — for his team and, above all, for himself. Riding high in the mid-Obama era, the trio wrote a book, titled, of course, “Young Guns,” that boldly demanded to know: “America urgently needs a new direction. But who will provide it?”

Spoiler alert: none of these guys.

Instead of remaking the party, the party wound up remaking the young guns — or, in some cases, simply kicking them to the curb. Mr. McCarthy hung on longer than the others, which was a real tribute to his ability to shape-shift as circumstances dictated. (...)

Of course, a shape-shifting, flip-flopping, overpromising, self-serving politician is nothing new. Where Mr. McCarthy truly distinguished himself was in his willingness and ability to debase himself in the service of Donald Trump — even as he occasionally pretended to still have a spine. “My Kevin,” as Mr. Trump so delighted in calling him, certainly did his part to aid Mr. Trump’s political revival after the Jan. 6 sacking of the Capitol. In a turnaround so dramatic it must have given him whiplash, Mr. McCarthy went from saying that Mr. Trump needed to “accept his share of responsibility” for his role in the attack to, some weeks later, slinking down to Mar-a-Lago for a grotesque photo op with the former president.

What could be more pathetic than this little field trip? Mr. McCarthy’s attempts to justify it. In “Oath and Honor,” the new book by Liz Cheney, the former congresswoman and Trump scourge, she dishes some dirt about confronting him.

“Mar-a-Lago? What the hell, Kevin?” she asked, according to CNN.

“They’re really worried,” Mr. McCarthy offered. “Trump’s not eating, so they asked me to come see him.”

Betraying democracy because the MAGA king’s appetite was off? Wow. Just wow.

Give Mr. McCarthy his due: All that butt smooching worked, kind of, allowing him to wheedle his way into his dream job for 11 not-so-glorious months. But having handed his leash to the right-wingers, he had no room left to do his job leading the House. And the moment he dared to cross them, using his deal-cutting, coalition-building skills to hammer out a bipartisan debt limit agreement and avoid crashing the global economy, he was a marked man. The extremists were on the prowl for any excuse to take him down, and come late September, the stopgap funding deal he cut to prevent a government shutdown filled the bill. A few days later, they snatched the gavel back from him, along with the last remaining shreds of his dignity.

It’s hard to dispute that this is the ending that Mr. McCarthy deserved. By contrast, the American people don’t deserve the damage that he has done to the House — and, really, the nation — that will linger long after he is gone. By empowering the most extreme elements of the Republican conference, he made an already fractured, fractious chamber even more dysfunctional. Worse, by shoring up Mr. Trump after Jan. 6, he helped put America back on a crash course with a dangerous, antidemocratic demagogue looking for political revenge.

These are Mr. McCarthy’s legacies. If he is remembered at all, it will be as a cautionary tale about what happens when one leaves it all on the field in the service of little more than blind ambition.

"Local Republican officials have been quick to sing McCarthy’s praises since the announcement of his retirement from Congress, calling him optimistic, unafraid of hard work, a patriot, and a “tremendous advocate for the Central Valley”. But others less beholden to him have been notable mostly by their silence.

Bakersfield’s mayor, Karen Goh, who has been photographed with McCarthy on passingly few occasions since she took office seven years ago, issued no statement. When invited to comment on ways in which McCarthy had helped the city in his 16 years in Washington, she told the Guardian she was too busy to respond."

And so I face the final curtain.

Come on! You know the Sinatra classic. Croon along with me as we emotionally gird ourselves for the closing act of Kevin McCarthy’s long, disappointing stint in Congress.

Having spent most of 2023 as a punching bag for his conference’s right flank, Mr. McCarthy has finally reached his pain threshold. At the end of this month, he announced on Wednesday, he will pack up his toys and flee the House, having made history as the first speaker booted from the job.

But do not cry for the former young gun. He has too few regrets to mention. As he bravely cheered his own performance in a Wall Street Journal essay announcing his departure, “I go knowing I left it all on the field — as always, with a smile on my face.”

Boy, did he. In his fevered pursuit of the gavel, Mr. McCarthy time and again prostrated himself before the altar of Donald Trump, sacrificing basically all the things that matter: his dignity, his integrity, his values (such as they were), his soul — you name it.

Now, looking back on each and every highway the congressman traveled to reach this point, I feel compelled to ask: Was it worth it, Kev?

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Mr. McCarthy came roaring into Washington from California in 2007 with big dreams and enormous promise. Alongside Paul Ryan and Eric Cantor, he was part of a new generation of fresh, feisty conservatives looking to overhaul what they saw as a stale, out-of-touch Republican Party.

Like an adorable boy band, the three pals each had a persona: Mr. Ryan, the policy wonk; Mr. Cantor, the blossoming leader; and Mr. McCarthy, the political animal. Mr. McCarthy was less concerned about policy or ideology than about mapping out the wins — for his team and, above all, for himself. Riding high in the mid-Obama era, the trio wrote a book, titled, of course, “Young Guns,” that boldly demanded to know: “America urgently needs a new direction. But who will provide it?”

Spoiler alert: none of these guys.

Instead of remaking the party, the party wound up remaking the young guns — or, in some cases, simply kicking them to the curb. Mr. McCarthy hung on longer than the others, which was a real tribute to his ability to shape-shift as circumstances dictated. (...)

Of course, a shape-shifting, flip-flopping, overpromising, self-serving politician is nothing new. Where Mr. McCarthy truly distinguished himself was in his willingness and ability to debase himself in the service of Donald Trump — even as he occasionally pretended to still have a spine. “My Kevin,” as Mr. Trump so delighted in calling him, certainly did his part to aid Mr. Trump’s political revival after the Jan. 6 sacking of the Capitol. In a turnaround so dramatic it must have given him whiplash, Mr. McCarthy went from saying that Mr. Trump needed to “accept his share of responsibility” for his role in the attack to, some weeks later, slinking down to Mar-a-Lago for a grotesque photo op with the former president.

What could be more pathetic than this little field trip? Mr. McCarthy’s attempts to justify it. In “Oath and Honor,” the new book by Liz Cheney, the former congresswoman and Trump scourge, she dishes some dirt about confronting him.

“Mar-a-Lago? What the hell, Kevin?” she asked, according to CNN.

“They’re really worried,” Mr. McCarthy offered. “Trump’s not eating, so they asked me to come see him.”

Betraying democracy because the MAGA king’s appetite was off? Wow. Just wow.

Give Mr. McCarthy his due: All that butt smooching worked, kind of, allowing him to wheedle his way into his dream job for 11 not-so-glorious months. But having handed his leash to the right-wingers, he had no room left to do his job leading the House. And the moment he dared to cross them, using his deal-cutting, coalition-building skills to hammer out a bipartisan debt limit agreement and avoid crashing the global economy, he was a marked man. The extremists were on the prowl for any excuse to take him down, and come late September, the stopgap funding deal he cut to prevent a government shutdown filled the bill. A few days later, they snatched the gavel back from him, along with the last remaining shreds of his dignity.

It’s hard to dispute that this is the ending that Mr. McCarthy deserved. By contrast, the American people don’t deserve the damage that he has done to the House — and, really, the nation — that will linger long after he is gone. By empowering the most extreme elements of the Republican conference, he made an already fractured, fractious chamber even more dysfunctional. Worse, by shoring up Mr. Trump after Jan. 6, he helped put America back on a crash course with a dangerous, antidemocratic demagogue looking for political revenge.

These are Mr. McCarthy’s legacies. If he is remembered at all, it will be as a cautionary tale about what happens when one leaves it all on the field in the service of little more than blind ambition.

by Michelle Cottle, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Haiyun Jiang for The New York Times

[ed. Good luck with that Wikipedia page. Power is such an intoxicating drug (really, the absolute worst). People are still jockeying for Trump's favor despite all evidence they'll eventually end up being smeared, humiliated, in court, or broke - just like everyone else who enters his orbit. It says all you need to know. Bottom feeders at the bottom of the barrel. See also: California hometown sheds few tears for retiring McCarthy: ‘Don’t let the door hit you on the way out, Kevin’ (The Guardian).]

[ed. Good luck with that Wikipedia page. Power is such an intoxicating drug (really, the absolute worst). People are still jockeying for Trump's favor despite all evidence they'll eventually end up being smeared, humiliated, in court, or broke - just like everyone else who enters his orbit. It says all you need to know. Bottom feeders at the bottom of the barrel. See also: California hometown sheds few tears for retiring McCarthy: ‘Don’t let the door hit you on the way out, Kevin’ (The Guardian).]

"Local Republican officials have been quick to sing McCarthy’s praises since the announcement of his retirement from Congress, calling him optimistic, unafraid of hard work, a patriot, and a “tremendous advocate for the Central Valley”. But others less beholden to him have been notable mostly by their silence.

Bakersfield’s mayor, Karen Goh, who has been photographed with McCarthy on passingly few occasions since she took office seven years ago, issued no statement. When invited to comment on ways in which McCarthy had helped the city in his 16 years in Washington, she told the Guardian she was too busy to respond."

Urban China

[ed. Whatever you imagine Chinese life to look like, it's probably not this. But...]

"Americans, used to their own shabby infrastructure and dowdy downtowns, often view these videos — or their own trips to these cities — as signs that China is “way ahead” of the West.

And so it may be. But there are a couple important subtleties that tend to get missed when people drool over these glowing skylines.

The first is about China’s style of urbanism. The montages of Chinese cities tend to look very different from montages of other Asian cities like Tokyo or Seoul or Hong Kong or Singapore, where the shots tend to focus on pedestrian spaces. There’s a reason for this; China has generally chosen a different approach to urbanism from other Asian countries. It’s more car-centric, with lots of giant highways and thoroughfares. The retail tends to be clustered in malls or other giant showpiece shopping centers rather than along walkable streets. Residential areas tend to be far from retail and commercial areas, clustered in ultra-high-density “superblocks”. This form of development has sometimes been referred to as “high-density sprawl”.

You can really see this when you look at ground-level videos of Chinese cities. Foot traffic tends to be concentrated in shopping malls or dedicated promenades, while the centers of cities are dominated by huge roads filled with cars. What walkable mixed-use pedestrian-friendly areas do exist tend to be very old, like Shanghai’s Bund and Old City. The skyscrapers and bridges do have plenty of spectacular LEDs on them — LED lighting has become very cheap in recent years — but this is perhaps necessary to break up the imposing, impersonal scale of these cities.

The reason these cities look like they were built for giants instead of people is that…well, they were. The “giants” here are corporations. As Michael Pettis would probably tell you, China over the last three decades has been a producer-centric economy, where the needs of construction companies and developers outweigh the needs of consumers. Giant skyscrapers and highways and concrete promenades and bridges and malls maximized the throughput of Chinese companies, so that’s what got built.

This type of urbanism surely showcases vast production capacity, but that doesn’t mean it necessarily makes Chinese cities amazing places to live, when compared with other Asian cities.

The other thing these videos neglect is capital depreciation. The more you build, the more you have to maintain. In 20 years, these glittering new buildings and infrastructure will begin to show their age; at that point, China’s government will have the choice to spend a lot of GDP upkeeping and rebuilding them (as Japan and Korea do) or letting them start to look a bit shabby, worn, and old on the outside (as Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the United States do).

Depreciation isn’t a mistake on China’s part; every country has to deal with it. But the cycle of new construction followed by depreciation does seem to give a lot of American visitors a very predictably biased impression of whether a country is “rising” or “declining”. In general, a city that looks like the “city of the future” is just one that was recently built.

But anyway, the LED skylines of Chinese cities are still fun, especially when set to some nice music."

"Americans, used to their own shabby infrastructure and dowdy downtowns, often view these videos — or their own trips to these cities — as signs that China is “way ahead” of the West.

And so it may be. But there are a couple important subtleties that tend to get missed when people drool over these glowing skylines.

The first is about China’s style of urbanism. The montages of Chinese cities tend to look very different from montages of other Asian cities like Tokyo or Seoul or Hong Kong or Singapore, where the shots tend to focus on pedestrian spaces. There’s a reason for this; China has generally chosen a different approach to urbanism from other Asian countries. It’s more car-centric, with lots of giant highways and thoroughfares. The retail tends to be clustered in malls or other giant showpiece shopping centers rather than along walkable streets. Residential areas tend to be far from retail and commercial areas, clustered in ultra-high-density “superblocks”. This form of development has sometimes been referred to as “high-density sprawl”.

You can really see this when you look at ground-level videos of Chinese cities. Foot traffic tends to be concentrated in shopping malls or dedicated promenades, while the centers of cities are dominated by huge roads filled with cars. What walkable mixed-use pedestrian-friendly areas do exist tend to be very old, like Shanghai’s Bund and Old City. The skyscrapers and bridges do have plenty of spectacular LEDs on them — LED lighting has become very cheap in recent years — but this is perhaps necessary to break up the imposing, impersonal scale of these cities.

The reason these cities look like they were built for giants instead of people is that…well, they were. The “giants” here are corporations. As Michael Pettis would probably tell you, China over the last three decades has been a producer-centric economy, where the needs of construction companies and developers outweigh the needs of consumers. Giant skyscrapers and highways and concrete promenades and bridges and malls maximized the throughput of Chinese companies, so that’s what got built.

This type of urbanism surely showcases vast production capacity, but that doesn’t mean it necessarily makes Chinese cities amazing places to live, when compared with other Asian cities.

The other thing these videos neglect is capital depreciation. The more you build, the more you have to maintain. In 20 years, these glittering new buildings and infrastructure will begin to show their age; at that point, China’s government will have the choice to spend a lot of GDP upkeeping and rebuilding them (as Japan and Korea do) or letting them start to look a bit shabby, worn, and old on the outside (as Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the United States do).

Depreciation isn’t a mistake on China’s part; every country has to deal with it. But the cycle of new construction followed by depreciation does seem to give a lot of American visitors a very predictably biased impression of whether a country is “rising” or “declining”. In general, a city that looks like the “city of the future” is just one that was recently built.

But anyway, the LED skylines of Chinese cities are still fun, especially when set to some nice music."

~ Some Thoughts on Chinese Urbanism (Noahpinion)

Labels:

Architecture,

Business,

Cities,

Culture,

Design,

Technology

Masahisa Fukase, "Family", a commemorative photographic collection of Fukase’s family taken between 1971 – 1989.

via:

via:

Friday, December 8, 2023

The Banality of Genius: Notes on Peter Jackson's Get Back

A friend of mine, a screenwriter in New York, believes Get Back has a catalytic effect on anyone who does creative work. Since it aired, he has been getting texts from fellow writers who, having watched it, now have the urge to meet up and work on something, anything, together.

This is strange, in a way, since the series does not present an obviously alluring portrait of creative collaboration. Its principal locations are drab and unglamorous: a vast and featureless film studio, followed by a messy, windowless basement. The catering consists of flaccid toast, mugs of tea, biscuits and cigarettes. The participants, pale and scruffy, seem bored, tired, and unhappy much of the time. None of them seem to know why they are there, what they are working on, or whether they have anything worth working on. As we watch them hack away at the same songs over and over again, we can start to feel a little dispirited too. And yet somewhere on this seemingly aimless journey, an alchemy takes place. (...)

Watching extraordinary people do ordinary things is also just oddly gripping. I loved witnessing the workaday mundanity of The Beatles’ creative life. Turning up for work - for the most part - every day, at an agreed time: Morning Paul. Morning George. Taking an hour for lunch, popping out for meetings. Sticking up your kid’s drawing by your workstation. Confessing to hangovers. Discussing TV from the night before. Fart jokes. Happy hour at the end of an afternoon. Coats on: Bye then. See you tomorrow. See you tomorrow.

Immersed in all this banality, a funny thing happens to the viewer. As we get into the rhythm of the Beatles’ daily lives, we start to inhabit their world. Since we live through their aimless wandering, we share in the moments of laughter, tenderness and joy that emerge from it with a special intensity. When they get up on that roof at the end of the final episode we feel exhilarated, joyful, and almost as thrilled as they look. I think we learn something along the way, too: that the anomie and the ecstasy are inseparable.

Let’s remind ourselves about how unwise, or if you prefer, insane, the Twickenham project was. The Beatles had only just finished a double album, the White Album (that was its nickname - I love hearing the Beatles call it “The Beatles”). It was a huge project and they had plenty of arguments in the making of it. Fortunately, it sold boatloads - their most commercially successful album to date. Paul and John have new girlfriends they’re very serious about. George is with Patti and hanging out with Dylan, Ringo has two young kids. In other words, they had every excuse, and every reason, to take six months or a year off. But no. In September, they enjoy making a promo for Hey Jude in front of a live audience, which rekindles their interest in performing, and they come up with a vague plan to do a TV special in the new year.

The initial idea was to perform songs from the White Album. That makes sense: using a show to perform songs from the album they just made is what ANY NORMAL BAND WOULD DO. But no. John and Paul get together before Christmas and decide they have to create a whole album’s worth of new songs, learn to play those while being filmed, and then perform them. That would be hard enough to achieve in three to six months. But because Ringo has to make a film they end up trying to cram all of this - writing, learning, rehearsing, show-planning - into three weeks. And they choose to do it all in an aircraft hangar.

The Beatles’ allergy to repetition, their relentless instinct to seek out the new rather than repackage the old, is here taken to such an extreme that it puts them in an absurd position. As a group, they were terrible at making non-musical decisions. They were much better at saying what they didn’t want to do than at making sensible plans for what they did want to do. So they ended up in this trap. As we watch the four Beatles try to escape from it, we are moved, because we see, for the first time, quite what a fragile creative entity they always were, and how hard they worked to stay together.

Nearly every Beatles album was perfect or close to it, a succession of immaculate conceptions. The Beach Boys, perhaps their closest artistic rivals, made some jewels, some stinkers, and some just-OK albums. That was typical, even for the best artists. There was something mysterious and implacable about The Beatles’ ability to keep a high standard at a high volume of output. It baffled their peers. Brian Wilson said of them, “They never did anything clumsy. (...)

Let It Be, the album that eventually emerged from the Get Back sessions, and the last new Beatles album to be released, has always been the closest thing to a glitch in this long run of jewels. Unfinished by the group, it is messy, uneven and incoherent by their standards, even though it contains a few songs that would be enough to turn most bands into legends by themselves. Today, Let It Be exists in various iterations, none of them definitive. One effect of Jackson’s Get Back is to find, or restore, a purpose to this loose strand from The Beatles’ recording career, by letting us in on a secret: they didn’t know what they were doing.

At one point in Get Back, during the endless discussion about why they’re all here, George Harrison reminds the others that The Beatles have never really made plans: “The things that have worked out best for us haven’t really been planned any more than this has. It’s just… like, you go into something and it does it by itself. Whatever it’s gonna be, it becomes that.” I think this represents a profound truth about The Beatles. They moved through the world in a dream, and the world became their dream.

by Ian Leslie, The Ruffian | Read more:

Image: Get Back

[ed. Thinking of re-watching this, but more closely this time instead of in big gulps.]

Thursday, December 7, 2023

Inside the A.I. Arms Race That Changed Silicon Valley Forever

Inside the A.I. Arms Race That Changed Silicon Valley Forever (NYT)

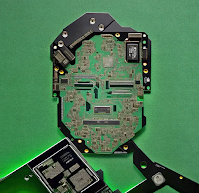

Image: Hokyoung Kim

[ed. This will get written into history - the reason AI alignment fails. If it does. How will we ever know?]

[ed. This will get written into history - the reason AI alignment fails. If it does. How will we ever know?]

Leaving Twitter

Twitter always used to look a lot like Craigslist. It stumbled into something that a lot of people found very useful, with very strong network effects, and then it squatted on those network effects for a generation, while the tech industry moved on. Twitter, as a technology company, has been irrelevant to everything that’s going on for a decade. It was the place where we talked about what mattered, but Twitter the company didn’t matter at all - indeed it did nothing for so long that people got bored of complaining about it.

Meanwhile, lots of people tried to build a better Craigslist and a better Twitter, but though a better product was pretty easy, the network effects were too strong and none of them really worked. Instead, we unbundled use cases one by one. As Andrew Parker pointed out in 2010, a whole range of people from Airbnb to Zillow to Tinder unbundled separate pieces of Craigslist into billion dollar companies that didn’t look like Craigslist and solved some individual need much better. This is often the real challenge to tech incumbents: once the network effects are locked in, it’s very hard to get people to switch to something that’s roughly the same but 10% better - they switch to something that solves one underlying need in an entirely new way.

Hence, Mastodon has been around since 2016 without getting much traction, but slices of conversation, content or industry have been unbundled to Reddit, LinkedIn, Instagram, Signal, Discord or, more recently, Substack, which someone joked was Twitter’s paywall.

Meanwhile, Twitter itself drifted aimlessly for a decade, becoming known in Silicon Valley as a place where no-one could get anything done. This is a big part of why Elon Musk was able to buy it - $44bn was a top-of-the-market price, but even Snap was worth $75bn in January 2022, when he started building a stake - how much bigger should Twitter have been? And so, when he made his bid, there was, briefly, a lot of enthusiasm in tech: pent-up frustration with the existing product and a sense of how much better it could be; enthusiasm that there could be innovation and new product ideas (and, from a small but noisy group, frustration with the politics of Twitter’s content policies, of which more in a moment).

It didn’t work out like that. The last year swapped stasis for chaos. Stuff breaks at random and you don’t know if it’s a bug or a decision. The advertisers have fled, and no-one knows what will be broken by accident or on purpose tomorrow. The example that’s closest to home for me was that the in-house newsletter product was shut down - and then links to other newsletters were banned. Pick one! It’s hard to see anyone who depends on having a long-term platform investing in anything that Twitter builds, when it might not be there tomorrow.

There are various diagnoses for this.

by Benedict Evans | Read more:

Image: Andrew Parker

[ed. Money will always have strange effects on people. But, not just money. Power. Musk controls one of the largest media platforms on the planet. Trump gets elected President. Nazi's make a comeback in the US (less than 75 years after WWII). AI charges full speed ahead with no apparent brakes. Weaponized capitalism is pervasive. Economic inequality is stratospheric. The world heats and burns. Meanwhile, trivia, celebrity, technological toys/distractions, sports and games rule the day. Overall, a civilizational mental health crisis/breakdown. See also: Elon Musk offers $1B to Wikipedia if it changes its name (The Hill):]"Billionaire Elon Musk offered Wikipedia, the free online encyclopedia, $1 billion under the condition that it changes its name to “Dickipedia.”

2023 Person of the Year

2023 Person of the Year, Taylor Swift (Time)

"Swift’s accomplishments as an artist—culturally, critically, and commercially—are so legion that to recount them seems almost beside the point. As a pop star, she sits in rarefied company, alongside Elvis Presley, Michael Jackson, and Madonna; as a songwriter, she has been compared to Bob Dylan, Paul McCartney, and Joni Mitchell. As a businesswoman, she has built an empire worth, by some estimates, over $1 billion. And as a celebrity—who by dint of being a woman is scrutinized for everything from whom she dates to what she wears—she has long commanded constant attention and knows how to use it. (“I don’t give Taylor advice about being famous,” Stevie Nicks tells me. “She doesn’t need it.”) But this year, something shifted. To discuss her movements felt like discussing politics or the weather—a language spoken so widely it needed no context. She became the main character of the world."

[ed. Well, not sure about all that but give her time. Loved this one comment, though: "Time named Taylor Swift its 2023 Person of the Year, and somehow made her look like Nicole Kidman on the cover." Haha. See also: Why Does Taylor Swift Want More? (Freddie deBoer):]

"I think it’s fair to say that Taylor Swift and her team ran a full-court press in 2023. You had the brief but massive success of her concert film, the continued release of the “Taylor’s version” series of re-recordings of her old material, absolutely constant media visibility, and of course the relentless publicizing of her relationship with Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce. The latter is a good example of choosing to expand your media footprint. There are some conspiracy theories that suggest that the relationship is all a sham; Kelce, at 34 years old, is clearly looking to set up a career as a media personality after football, and the endless shots of Swift in a luxury box at NFL games have taken her inescapability to a new high. I have no opinion about and no interest in those theories. I do want to stress, though, that had she wanted it, that relationship could have been much quieter. She certainly has the juice to say to the NFL “I want to sit in privacy in the back of a luxury box with no cameras on me, and plus let my team in the back of the stadium with no publicity.” She chose to do the opposite and make this romance as public as possible. That’s generally been her MO in 2023 - whenever she’s had the opportunity to go bigger, get richer, get more famous, harvest more attention, she’s pursued that opportunity with gusto.

Hey, look! Yet another august academic institution is giving a course on Taylor Swift! That’s fun! Isn’t this fun? Aren’t we all having fun? (...)

It’s also the case that I think this stuff has reached a level of absolute madness, that the sense that no matter how obsessed we are with this woman, it’s never enough, is genuinely creepy and reflects a deeply diseased society. I’m genuinely frightened by her fanbase; they are as vindictive and remorseless a social force as I can remember in online life. Personally, I think people are fixated on Swift in this way because they’re lonely and directionless and lack any source of transcendent meaning, and have tried to invest celebrity with the hopes that once accrued to God or country or the party, and I further think that this is bound to result in inevitable disillusionment and sadness."

I’m interested in a different issue: why does Swift harbor such a palpable feeling that she needs even more success? 15 years after “You Belong With Me” was released, she’s grinding more than ever, clawing for more and more presence in the national popular consciousness. Her vast professional apparatus has worked relentlessly to make sure that she stays in said popular consciousness. And my question is… why? For what? What does she want, that she does not already have? What need could she fill that hasn’t already been filled? She has more of everything than almost any human being who has ever lived. Why does she need more than more?

[ed. Because that's what she does? The satisfaction of running a well-oiled, precision machine? Of your own making? It's not complicated.]

You Good?

Do not under any circumstances give me a hug

As the weather turns grim, daylight barely lasts the length of a work day, and a chain of winter holidays promises to agitate even the most stable New Yorker's nerves, the number of people crying on the subway or on a park bench or while shuffling down the street is likely to increase—and I’d like to remind the people of New York City that this hugging and chatting business is usually not, in fact, what we do.

One of the truest and most sublime rights we possess in a trash-strewn city of 8.5 million is to cry in public unbothered, ideally next to a bottle of piss or over the bone-crunching sound of an elevated train. It’s a ritual to be respected—in most cases, the perfect collective anonymity of the city offers a more private weeping experience than in an apartment or office, where you might encounter a person who feels compelled to ask how they might help. In extreme cases, when it’s possible someone is experiencing such a wave of preventable agitation or grief you feel moved to alleviate it in some way there is only one course of action: You ask that person, briefly and politely, if they’re good.

It is my personal opinion that if you encounter a crying person on the train, your sole responsibility as a New Yorker is to do something sort of psycho in their general vicinity in order to compound the weepers’ sorrow and make a great story later on. There’s something poetic and deeply affirming about having a bad time surrounded by weirdos and/or filth. On one occasion, I cried next to an insufferable bachelor party in Midtown as men in mirrored sunglasses detailed last night's grotesque exploits. A friend of mine cried into a plate of mozzarella sticks at the Applebees in Downtown Brooklyn at 11:00 in the morning to a Fiona Apple song. No one asked for a hug because it would have been obscene, an aberration in the therapeutic practice of feeling sad and sorry for yourself in a place that will continue churning at a rapid clip no matter how you, an insignificant speck, happen to feel.

by Molly Osberg, Hell Gate | Read more:

Image: Zhivko Minkov/UnsplashWednesday, December 6, 2023

It's Official: Golf Ball Distances To Be Restricted (and Drivers Might Be Next)

It’s official. Golf, but shorter.

The USGA and the R&A formally announced Wednesday their intention to roll back the distance golf balls can travel. The rollback goes into effect January 2028 for elite competitions and for everybody come January 2030. The decision, part of the governing bodies’ Distance Insights Project, comes after some three years of “Notice and Comment” in which the USGA and R&A accepted feedback from golf’s stakeholders.

“Governance is hard. And while thousands will claim that we did too much, there will be just as many who said we didn’t do enough to protect the game long-term,” said Mike Whan, CEO of the USGA. “But from the very beginning, we’ve been driven to do what is right for the game, without bias. As we’ve said, doing nothing is not an option—and we would be failing in our responsibility to protect the game’s future if we didn’t take appropriate action now.”

The specifics, first reported by Golf Digest, involve the test for the Overall Distance Standard. The governing bodies are increasing the swing speed at which golf balls are tested from the current standard of 120 mph to 125 mph without changing the distance limit of 317 yards (plus a three-yard tolerance) with a launch angle of 11 degrees and 2,200 rpm of spin. In layman’s terms, according to the USGA and R&A, the effect could be a distance loss of nine to 11 yards at the PGA Tour or DP World Tour level, five to seven yards for the LPGA/LET and between five yards or less for everyday players.

All golf balls submitted to the USGA for conformance during or after October 2027 will be evaluated using the new protocol. In other words, if everyday golfers want to continue using longer golf balls in 2028 and 2029, they will be older-model balls. There was no mention in the Notice of Decision how one would be able to tell what is an old conforming ball and what is a new conforming ball other than comparing it to the conforming list. However, John Spitzer, the USGA's managing director of equipment standards, said approximately one-third of balls currently on the conforming list would still be conforming under the new protocol, primarily two- and-three piece balls with ionomer covers.

The change in speed and the fact it affects all golfers are significant departures from the governing bodies previous stance. In 2022, the speed being looked at was 125 mph but that was amended in March 2023 to 127. However, also at that time the proposal was stated as a Model Local Rule impacting elite professional golfers only. Said Whan at the time, “We don’t see recreational golf obsoleting golf courses any time soon."

So why the change to include everybody? The governing bodies say the move to a universal rollback was the result of feedback during the Notice and Comment period triggered in March after the announcement of the proposed MLR. In a note to all industry stakeholders, the USGA and R&A conveyed that, “While we previously proposed a targeted change to only elite golf, we have incorporated feedback from a broad range of stakeholders/players who stressed the importance of unification in the game of golf, mainly the importance of maintaining a single set of playing rules and a single set of equipment standards. This feedback clearly indicated that an across-the-game solution with deferred implementation is the preferred solution.” (...)

"It's five yards at most and likely limited to your driver," Pagel said. "I don't want to minimize people's feelings or concerns about losing even a yard. We all have those concerns. We all want that extra yard or two. But just put this in the practical senses of this would mean, you know, 222 yards instead of 225. And you do have the ability to move tees up. You do have the ability to play forward tees. I would just say trust in the process. Over the next six years, I think we'll find that the sky hasn't fallen, the game is still going to be healthy.”

Perhaps just as important as the decision on golf balls, it appears the governing bodies are not quite done putting a governor on distance. Included in the note to stakeholders were two additional areas being looked at. The first is expanding testing of submitted drivers to keep tabs on “CT Creep,” which is drivers getting springier over time due to use, leading to the possibility of a conforming club becoming non-conforming. This is not a change, per se, and does not impact everyday players.

The next item, however, is to continue its research into the forgiveness of drivers at the elite level, which could lead to reductions in moment of inertia (which mitigates distance loss on mis-hits), driver-head size or both. Although the language was aimed solely at elite players, as we have seen with the ball rollback decision, things have a way of changing.

by E. Michael Johnson, Golf Digest | Read more:

Image: uncredited

[ed. Distance is overrated (for most of us). Just get better with all your clubs (especially around greens). I imagine (as with previous restrictions on driver size, COR, anchored 'broomstick' putters, etc.) this will blow over soon enough. Rory McIlroy had the best response, I think (see here); but there were opposing perspectives too (see here). Nearly everyone agrees something had to be done - you can't just keep increasing the length of golf courses, and it's no fun watching the game reduced to simple bomb and gounge driver/wedge shots. It's up to the engineers to figure it all out now. More on the rollback here (SI).]

Tuesday, December 5, 2023

Isaiah Collier

[ed. See also: Open the Door.]

Monday, December 4, 2023

The Cocktail Revolution

If you’ve sidled up to bars over the past decade or two, you’ve probably noticed a change. Gone are the days of boat-sized, vaguely fruity concoctions listed out on a menu of x-tinis; of haphazardly made Old-Fashioneds topped with club soda and what might as well be a complete fruit salad. Sour mix is out, and fresh juice and homemade syrups are in.

Bars – especially those billing themselves as cocktail bars, but also restaurants with what we now call ‘cocktail programs’ – are taking time with their drinks, carefully measuring ingredients, making syrups and infusions in-house. They painstakingly press and strain fresh juice (or construct acid-adjusted simulacra of the same), reconstruct long-forgotten classics and obscurities, and build novel drinks out of an ever-expanding array of unusual, unexpected, and – even to sophisticated drinkers – largely unknown ingredients. If you want a Manhattan variation made with Fey Anmè – a forest liqueur inspired by Haitian botanicals and made from hibiscus buds, dandelion, and bitter melon . . . well, some enterprising bartender probably has you covered. And if not, with a little bit of effort, you can probably stir one up at home.

But as much as anything, the revitalization of the cocktail has been built on an obsession with ingredient quality and variety, and a pursuant explosion in product availability. Put simply, cocktails are better and more interesting because what we put in them is better and more interesting, thanks to a combination of demand from knowledgeable practitioners and supply from importers and entrepreneurs delivering products to meet that demand.

As modern cocktails continue to evolve, so will the revolution in ingredients, as ever more sophisticated customized creations become part of the tool kit for both top-flight bars and home bartenders. Indeed, you can already see the seeds of the next stage of the renaissance beginning to flower, as modern cocktail wizards apply increasingly abstruse culinary techniques to both classic drinks and novel creations.

Bars – especially those billing themselves as cocktail bars, but also restaurants with what we now call ‘cocktail programs’ – are taking time with their drinks, carefully measuring ingredients, making syrups and infusions in-house. They painstakingly press and strain fresh juice (or construct acid-adjusted simulacra of the same), reconstruct long-forgotten classics and obscurities, and build novel drinks out of an ever-expanding array of unusual, unexpected, and – even to sophisticated drinkers – largely unknown ingredients. If you want a Manhattan variation made with Fey Anmè – a forest liqueur inspired by Haitian botanicals and made from hibiscus buds, dandelion, and bitter melon . . . well, some enterprising bartender probably has you covered. And if not, with a little bit of effort, you can probably stir one up at home.

This is a far cry from the simplistic, slapdash, thoughtlessly boozy drinking culture that ruled from the 1970s through the 1990s. It’s fussy, precise, thoughtful – at times almost overeducated – and it has resulted in a rapid improvement in the quality and creativity of craft cocktails since the turn of the century. This period of improvement has been called the cocktail renaissance.

The question of how, exactly, modern cocktails achieved such significant quality gains in such a short period of time has been answered in book-length form by multiple authors, including but not limited to cocktail writer Robert Simonson (A Proper Drink), bartender and drinks expert Derek Brown (Spirits Sugar Water Bitters), and cocktail historian David Wondrich (Imbibe!). Many factors contributed to the boom, including the role of the internet in information sharing, the long tail of the culinary revolution that began in the 1970s, the evolution of craft beer and the elevated expectations of educated drinkers that went along with it, and a renewed emphasis on rigorous bartending technique.

But as much as anything, the revitalization of the cocktail has been built on an obsession with ingredient quality and variety, and a pursuant explosion in product availability. Put simply, cocktails are better and more interesting because what we put in them is better and more interesting, thanks to a combination of demand from knowledgeable practitioners and supply from importers and entrepreneurs delivering products to meet that demand.

As modern cocktails continue to evolve, so will the revolution in ingredients, as ever more sophisticated customized creations become part of the tool kit for both top-flight bars and home bartenders. Indeed, you can already see the seeds of the next stage of the renaissance beginning to flower, as modern cocktail wizards apply increasingly abstruse culinary techniques to both classic drinks and novel creations.

------

To understand the role that ingredient availability has played in the cocktail renaissance, consider the Aviation.The Aviation is a shaken gin-based cocktail with a distinctive lavender hue; conceptually, it’s best understood as a tailored variation of the sour – a broad cocktail category that, in its most basic form, involves a spirit, citrus juice, and some sort of sugar or other sweetener.

The first known appearance of the classic recipe came in Hugo R. Ensslin’s pre-Prohibition cocktail guide, Recipes for Mixed Drinks. In Ensslin’s formulation, the drink calls for four ingredients, as follows:

Modern readers might notice a few historical quirks about the recipe. For one thing, there are no units of measurement specified – no ounces, no teaspoons, just ratios and ‘dashes’. The book was published in 1916, before today’s standardized measurements were in use.

For another, the listing of ‘maraschino’ would have referred to some form of maraschino-flavored liqueur. Today, there are multiple brands available in many parts of the country, and even if a recipe writer did not specify a brand, he or she would probably have noted the fact that it’s a liqueur in order to differentiate it from the thick, sugary, nonalcoholic syrup one finds in a bottle of preserved maraschino cherries.

And then there is that final ingredient: crème de violette. Crème de violette is exactly what it sounds like – a ‘crème’ or sweet liqueur flavored with, among other things, flowers. It’s purplish in tint, and it can give the cocktail a distinctive lavender hue. Arguably, it’s the cocktail’s signature ingredient, the element that piques a drinker’s interest both in terms of how it looks and how it tastes.

Flash forward to the turn of century, however, and the ingredient had disappeared. New York Times cocktail scribe William Grimes once reportedly told cocktail enthusiast and author Ted Haigh that the Aviation was his favorite forgotten cocktail. But in Straight Up or On the Rocks, Grimes’s groundbreaking 2001 book of cocktail history and recipes, a recipe for the Aviation appears without any mention of crème de violette. Other highly regarded, thoroughly researched cocktail books from around the same time followed suit: Haigh’s book Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails prints an Aviation recipe without the flower liqueur, as does legendary bartender Dale DeGroff’s book The Essential Cocktail.

Both Haigh and DeGroff are modern legends in the cocktail world, known for their thorough research and exacting cocktail preparation methods. Both would have been aware of Ensslin’s original, historic formulation. So why the omission?

One reason is that more than a decade after Ensslin’s book appeared, British bartender Harry Craddock published The Savoy Cocktail Book, which compiled drinks served at the Savoy Hotel in London. It has since become a sacred text for bartenders, and Craddock’s version of the Aviation did not include any crème de violette. (Haigh also writes that the original had both maraschino and either crème de violette or Crème Yvette, a proprietary violet petal liqueur, and notes that substituting either Yvette or crème de violette for maraschino results in a different cocktail: the Blue Moon.)

Another reason, however, is availability. Even as recently as the 2000s, crème de violette was all but impossible to obtain in the United States.

Crème de violette was produced in Europe, and Prohibition’s near-total restriction on alcohol sales and purchases shut down legal trade in spirits through the 1920s and early 1930s. Meanwhile, according to Dinah Sanders’s entry in The Oxford Companion to Spirits and Cocktails, European interest in crème de violette faded around the same time, in part because some felt the flowery spirit tasted a bit too much like soap.

So even though Prohibition ended in 1933, crème de violette did not return to American bars and liquor stores. The unique floral booze was gone from domestic distribution, and while one could still obtain a bottle in France, even there it was relatively obscure. Thus, Ensslin’s Aviation became a thing of legend.

At least, that is, until the late 2000s. Credit for the return of crème de violette goes to spirits and wine importer Eric Seed. In 2005, Seed founded Haus Alpenz, initially to distribute a relatively obscure Australian pine liqueur, Zirbenz Stone Pine Liqueur of the Alps, which he marketed to upscale bars at ski resorts, according to a 2009 Atlantic article on Seed’s importing business.

But Seed was also aware of growing interest in other arcane ingredients, including some liqueurs mentioned in historical cocktail recipe books that could no longer be found in American liquor stores. So in 2007, Sanders writes, Haus Alpenz responded to ‘a small but persistent demand from modern mixologists’ by bringing crème de violette back to the US via the Rothman & Winter brand. Its primary intended use was as a cocktail ingredient for the nascent cocktail revival.

At first, it was difficult to find, as many liquor stores didn’t see the need to stock something so strange and obscure. But a small number of dedicated craft cocktail bartenders began to put the Aviation on their menus or make them off-menu for friends, and within several years, crème de violette became one of Seed’s top sellers. By the early 2010s, the drink became a sort of secret handshake between discerning drinkers and barkeeps – a wink and a nod between those who knew.

Today, you can order or make at home any number of purple-hued drinks that use the stuff. Some, like the Purple Reign 75, a riff on the French 75, are modern riffs on historical cocktails. Others are wholly modern creations like the Stormy Morning, which combines one flower ingredient with another – elderflower liqueur. If you’ve ever seen a lilac-colored cocktail served at a bar, there’s a good chance that it was made with crème de violette.

The first known appearance of the classic recipe came in Hugo R. Ensslin’s pre-Prohibition cocktail guide, Recipes for Mixed Drinks. In Ensslin’s formulation, the drink calls for four ingredients, as follows:

- ⅓ lemon juice

- ⅔ El-Bart gin

- 2 dashes maraschino

- 2 dashes crème de violette

Modern readers might notice a few historical quirks about the recipe. For one thing, there are no units of measurement specified – no ounces, no teaspoons, just ratios and ‘dashes’. The book was published in 1916, before today’s standardized measurements were in use.

For another, the listing of ‘maraschino’ would have referred to some form of maraschino-flavored liqueur. Today, there are multiple brands available in many parts of the country, and even if a recipe writer did not specify a brand, he or she would probably have noted the fact that it’s a liqueur in order to differentiate it from the thick, sugary, nonalcoholic syrup one finds in a bottle of preserved maraschino cherries.

And then there is that final ingredient: crème de violette. Crème de violette is exactly what it sounds like – a ‘crème’ or sweet liqueur flavored with, among other things, flowers. It’s purplish in tint, and it can give the cocktail a distinctive lavender hue. Arguably, it’s the cocktail’s signature ingredient, the element that piques a drinker’s interest both in terms of how it looks and how it tastes.

Flash forward to the turn of century, however, and the ingredient had disappeared. New York Times cocktail scribe William Grimes once reportedly told cocktail enthusiast and author Ted Haigh that the Aviation was his favorite forgotten cocktail. But in Straight Up or On the Rocks, Grimes’s groundbreaking 2001 book of cocktail history and recipes, a recipe for the Aviation appears without any mention of crème de violette. Other highly regarded, thoroughly researched cocktail books from around the same time followed suit: Haigh’s book Vintage Spirits and Forgotten Cocktails prints an Aviation recipe without the flower liqueur, as does legendary bartender Dale DeGroff’s book The Essential Cocktail.

Both Haigh and DeGroff are modern legends in the cocktail world, known for their thorough research and exacting cocktail preparation methods. Both would have been aware of Ensslin’s original, historic formulation. So why the omission?

One reason is that more than a decade after Ensslin’s book appeared, British bartender Harry Craddock published The Savoy Cocktail Book, which compiled drinks served at the Savoy Hotel in London. It has since become a sacred text for bartenders, and Craddock’s version of the Aviation did not include any crème de violette. (Haigh also writes that the original had both maraschino and either crème de violette or Crème Yvette, a proprietary violet petal liqueur, and notes that substituting either Yvette or crème de violette for maraschino results in a different cocktail: the Blue Moon.)

Another reason, however, is availability. Even as recently as the 2000s, crème de violette was all but impossible to obtain in the United States.

Crème de violette was produced in Europe, and Prohibition’s near-total restriction on alcohol sales and purchases shut down legal trade in spirits through the 1920s and early 1930s. Meanwhile, according to Dinah Sanders’s entry in The Oxford Companion to Spirits and Cocktails, European interest in crème de violette faded around the same time, in part because some felt the flowery spirit tasted a bit too much like soap.

So even though Prohibition ended in 1933, crème de violette did not return to American bars and liquor stores. The unique floral booze was gone from domestic distribution, and while one could still obtain a bottle in France, even there it was relatively obscure. Thus, Ensslin’s Aviation became a thing of legend.

At least, that is, until the late 2000s. Credit for the return of crème de violette goes to spirits and wine importer Eric Seed. In 2005, Seed founded Haus Alpenz, initially to distribute a relatively obscure Australian pine liqueur, Zirbenz Stone Pine Liqueur of the Alps, which he marketed to upscale bars at ski resorts, according to a 2009 Atlantic article on Seed’s importing business.

But Seed was also aware of growing interest in other arcane ingredients, including some liqueurs mentioned in historical cocktail recipe books that could no longer be found in American liquor stores. So in 2007, Sanders writes, Haus Alpenz responded to ‘a small but persistent demand from modern mixologists’ by bringing crème de violette back to the US via the Rothman & Winter brand. Its primary intended use was as a cocktail ingredient for the nascent cocktail revival.

At first, it was difficult to find, as many liquor stores didn’t see the need to stock something so strange and obscure. But a small number of dedicated craft cocktail bartenders began to put the Aviation on their menus or make them off-menu for friends, and within several years, crème de violette became one of Seed’s top sellers. By the early 2010s, the drink became a sort of secret handshake between discerning drinkers and barkeeps – a wink and a nod between those who knew.

Today, you can order or make at home any number of purple-hued drinks that use the stuff. Some, like the Purple Reign 75, a riff on the French 75, are modern riffs on historical cocktails. Others are wholly modern creations like the Stormy Morning, which combines one flower ingredient with another – elderflower liqueur. If you’ve ever seen a lilac-colored cocktail served at a bar, there’s a good chance that it was made with crème de violette.

And Rothman & Winter is no longer the only brand that produces it; there are now at least a half dozen brands available. I currently possess three different bottles, each with its own subtly different character – one is a little sweeter, one is a little more floral, one is a little more earthy. They all work in an Aviation cocktail, but the drink’s flavor profile differs subtly depending on which bottle you employ.

The story of the Aviation, then, is the story of the entire cocktail renaissance – a story of rediscovery and revitalization, with novel ingredients coming back to the bar.

The story of the Aviation, then, is the story of the entire cocktail renaissance – a story of rediscovery and revitalization, with novel ingredients coming back to the bar.

by Peter Suderman, Works in Progress | Read more:

Image: The Spruce Eats/Cara Cormack via

A Simple Theory of Cancel Culture

Now that everyone’s tired of talking about cancel culture, it seems about the right time for us academics to weigh in. I recently read with interest Eve Ng’s Cancel Culture: A Critical Analysis, which isn’t really all that critical but does provide a useful history of the phenomenon. Unfortunately, it does not offer a clear definition or explanation of what has been going on, merely a profusion of examples. My goal here is to correct that deficiency, by providing a simple theory of cancel culture, based on an analysis of the underlying social dynamics.

In order to get going on the discussion, the first thing that needs to be made clear is that the origins of cancel culture are neither political nor cultural. Cancel culture arises from a structural change in the dynamics of social interaction facilitated by the development of social media. This is reflected in the fact that its basic features (manifest in what Ng refers to as cancellation practices) have been observed in countries all over the world and have been mobilized by individuals with a wide range of different political orientations.

In the United States, criticism of cancel culture has been deeply interwoven with controversies over “woke” politics, but as many commentators have noted, the internal dynamics of the Republican party exhibit many of the same characteristics. Fear of being labelled a RINO or cuck has had a disciplining effect on speech among conservatives that closely resembles the tyranny of speech codes on the left. So there is nothing intrinsically left-wing or woke about cancel culture. Furthermore, it is not a consequence of political polarization in the U.S., since cancellation has become an enormous issue in China as well, in this case with nationalist mobs policing online speech for minor slights, then extracting groveling confessions and apologies from celebrities.

Just this morning, I read an article about a Chinese chef who is being cancelled for posting a fried rice recipe on Weibo. (“As a chef, I will never make egg fried rice again,” Wang Gang, a celebrity chef with more than 10 million online fans, pledged in a video message on Monday. Wang’s “solemn apology” attempted to tame a frothing torrent of criticism about the video… ”) Sound familiar?

Reading this, any sensible person should be able to see there’s something going on that is new, weird, concerning, and much bigger and more important than our petty domestic political disputes. At the same time, it should be acknowledged that some people are still hold-outs, claiming that there is no such thing as cancel culture, that it’s just consequence culture, and so on. In my experience, this is a defensive reaction among those who enjoy participating in cancellation practices, most of whom seem to have a bad case of the “are we the baddies?” problem:

To put it simply, if you still don’t think that cancel culture is a problem, it’s probably because you’re a part of the problem.

On the other hand, apologists for cancel culture are correct to point out that there is nothing new about the reactions that certain forms of online speech are eliciting. That is, the social dynamics involved in cancel culture are not novel, they have been a feature of human social interaction for as long as we know. The difference is that certain strategies that individuals employ to manage interpersonal conflict have been potentiated by social media, generating mass phenomena that pose a new set of challenges.

Put succinctly, social media have dramatically expanded the power to individuals to recruit third parties to conflict. Human beings are distinctive in a variety of different ways, but one of the most important is that otherwise uninvolved third parties will often intervene in conflicts that erupt between strangers. In some cases this involves enforcement of the normative order. (...)

It’s not difficult to see how the internet generates massive amplification of people’s ability to solicit allies. Everyday conflicts that would traditionally have come and gone without notice to anyone but the parties involved can now be publicly prosecuted. People need only shoot some video, or take a picture, post it online, and invite others to take their side. It is often not difficult to find thousands, tens of thousands, sometimes even millions, who are happy to oblige. Consider this rather quotidian post to the /mildlyinfuriating subbreddit, which received over 4,400 upvotes and 176 comments, promoting it to the front page (“This is how my husband loads the dishwasher”):

This is the world we now live in. You can come home from work one day to find out, not just that your wife is mad at you, but that she has literally thousands of people on her side.

Of course, the idea that a minor domestic conflict of this sort should be a private matter, to be resolved among those directly affected, is a relatively recent one. As the institution of the charivari makes clear, people in medieval European societies took a keen interest in one another’s domestic affairs. Private life, as most of us understand it, is an 18th century innovation. The important point is not that society is reverting to an older set of norms, but that the scale of third-party intervention is vastly greater. This has dramatically enhanced people’s ability to escalate conflict, which has two notable effects. First, it has resulted in many minor conflicts, such as routine violations of etiquette, becoming much more severely contested and sanctioned. Second, it has made it possible to intimidate individuals and institutions in ways that had previously not been possible.

All of the talk about “social justice” has obscured many of these dynamics – the appropriate lens through which to understand the phenomenon of cancel culture is that of conflict theory. Indeed, one of the most frustrating things about contemporary “victimhood culture” is that so many complaints are lodged in a way that is self-evidently a form of relational aggression. This explains also why criticisms of cancel culture are likely to be ineffective at making it go away. The underlying human propensity to recruit third parties to conflict is unlikely to change, and the technological amplification of this capacity is clearly irreversible. Thus cancellation practices are not going to disappear. The only productive question is whether the way that people respond to these practices is likely to change.

Societies with strong institutions become wealthier, more powerful militarily, or some combination of the two. These are the ones whose culture reproduces, either because it is imitated, or because it is imposed on others. And yet the dominant trend in human societies, over the past century, has been significant convergence with respect to institutional structure. Most importantly, there has been practically universal acceptance of the need for a market economy and a bureaucratic state as the only desirable social structure at the national level. One can think of this as the basic blueprint of a “successful” society. This has led to an incredible narrowing of cultural possibilities, as cultures that are functionally incompatible with capitalism or bureaucracy are slowly extinguished.

This winnowing down of cultural possibilities is what constitutes the trend that is often falsely described as “Westernization.” Much of it is actually just a process of adaptation that any society must undergo, in order to bring its culture into alignment with the functional requirements of capitalism and bureaucracy. It is not that other cultures are becoming more “Western,” it is that all cultures, including Western ones, are converging around a small number of variants."

In order to get going on the discussion, the first thing that needs to be made clear is that the origins of cancel culture are neither political nor cultural. Cancel culture arises from a structural change in the dynamics of social interaction facilitated by the development of social media. This is reflected in the fact that its basic features (manifest in what Ng refers to as cancellation practices) have been observed in countries all over the world and have been mobilized by individuals with a wide range of different political orientations.

In the United States, criticism of cancel culture has been deeply interwoven with controversies over “woke” politics, but as many commentators have noted, the internal dynamics of the Republican party exhibit many of the same characteristics. Fear of being labelled a RINO or cuck has had a disciplining effect on speech among conservatives that closely resembles the tyranny of speech codes on the left. So there is nothing intrinsically left-wing or woke about cancel culture. Furthermore, it is not a consequence of political polarization in the U.S., since cancellation has become an enormous issue in China as well, in this case with nationalist mobs policing online speech for minor slights, then extracting groveling confessions and apologies from celebrities.

Just this morning, I read an article about a Chinese chef who is being cancelled for posting a fried rice recipe on Weibo. (“As a chef, I will never make egg fried rice again,” Wang Gang, a celebrity chef with more than 10 million online fans, pledged in a video message on Monday. Wang’s “solemn apology” attempted to tame a frothing torrent of criticism about the video… ”) Sound familiar?

Reading this, any sensible person should be able to see there’s something going on that is new, weird, concerning, and much bigger and more important than our petty domestic political disputes. At the same time, it should be acknowledged that some people are still hold-outs, claiming that there is no such thing as cancel culture, that it’s just consequence culture, and so on. In my experience, this is a defensive reaction among those who enjoy participating in cancellation practices, most of whom seem to have a bad case of the “are we the baddies?” problem:

To put it simply, if you still don’t think that cancel culture is a problem, it’s probably because you’re a part of the problem.

On the other hand, apologists for cancel culture are correct to point out that there is nothing new about the reactions that certain forms of online speech are eliciting. That is, the social dynamics involved in cancel culture are not novel, they have been a feature of human social interaction for as long as we know. The difference is that certain strategies that individuals employ to manage interpersonal conflict have been potentiated by social media, generating mass phenomena that pose a new set of challenges.

Put succinctly, social media have dramatically expanded the power to individuals to recruit third parties to conflict. Human beings are distinctive in a variety of different ways, but one of the most important is that otherwise uninvolved third parties will often intervene in conflicts that erupt between strangers. In some cases this involves enforcement of the normative order. (...)

It’s not difficult to see how the internet generates massive amplification of people’s ability to solicit allies. Everyday conflicts that would traditionally have come and gone without notice to anyone but the parties involved can now be publicly prosecuted. People need only shoot some video, or take a picture, post it online, and invite others to take their side. It is often not difficult to find thousands, tens of thousands, sometimes even millions, who are happy to oblige. Consider this rather quotidian post to the /mildlyinfuriating subbreddit, which received over 4,400 upvotes and 176 comments, promoting it to the front page (“This is how my husband loads the dishwasher”):

This is the world we now live in. You can come home from work one day to find out, not just that your wife is mad at you, but that she has literally thousands of people on her side.

Of course, the idea that a minor domestic conflict of this sort should be a private matter, to be resolved among those directly affected, is a relatively recent one. As the institution of the charivari makes clear, people in medieval European societies took a keen interest in one another’s domestic affairs. Private life, as most of us understand it, is an 18th century innovation. The important point is not that society is reverting to an older set of norms, but that the scale of third-party intervention is vastly greater. This has dramatically enhanced people’s ability to escalate conflict, which has two notable effects. First, it has resulted in many minor conflicts, such as routine violations of etiquette, becoming much more severely contested and sanctioned. Second, it has made it possible to intimidate individuals and institutions in ways that had previously not been possible.

All of the talk about “social justice” has obscured many of these dynamics – the appropriate lens through which to understand the phenomenon of cancel culture is that of conflict theory. Indeed, one of the most frustrating things about contemporary “victimhood culture” is that so many complaints are lodged in a way that is self-evidently a form of relational aggression. This explains also why criticisms of cancel culture are likely to be ineffective at making it go away. The underlying human propensity to recruit third parties to conflict is unlikely to change, and the technological amplification of this capacity is clearly irreversible. Thus cancellation practices are not going to disappear. The only productive question is whether the way that people respond to these practices is likely to change.

by Joseph Heath, In Due Course | Read more:

Image: uncredited

[ed. See also: Just Stop Making Official Statements About the News. A simple answer for every CEO, school president, and City Council (Intelligencer); Interesting site. See also, The futility of arguing against identity politics (IDC); and, Why the Culture Wins: An Appreciation of Iain M. Banks:]

[ed. See also: Just Stop Making Official Statements About the News. A simple answer for every CEO, school president, and City Council (Intelligencer); Interesting site. See also, The futility of arguing against identity politics (IDC); and, Why the Culture Wins: An Appreciation of Iain M. Banks:]

"In this context, what distinguishes Banks’ work is that he imagines a scenario in which technological development has also driven changes in the social structure, such that the social and political challenges people confront are new. Indeed, Banks distinguishes himself in having bothered to think carefully about the social and political consequences of technological development. For example, once a society has semi-intelligent drones that can be assigned to supervise individuals at all times, what need is there for a criminal justice system? Thus in the Culture, an individual who commits a sufficiently serious crime is assigned – involuntarily – a “slap drone,” who simply prevents that person from committing any crime again. Not only does this reduce recidivism to zero, the prospect of being supervised by a drone for the rest of one’s life also serves as a powerful deterrent to crime.

This is an absolutely plausible extrapolation from current trends – even just looking at how ankle monitoring bracelets work today. But it also raises further questions. For instance, once there is no need for a criminal justice system, one of the central functions of the state has been eliminated. This is one of the social changes underlying the political anarchism that is a central feature of the Culture. There is, however, a more fundamental postulate. The core feature of Banks’s universe is that he imagines a scenario in which technological development has freed culture from all functional constraints – and thus, he imagines a situation in which culture has become purely memetic. This is perhaps the most important idea in his work, but it requires some unpacking. (...)

This is an absolutely plausible extrapolation from current trends – even just looking at how ankle monitoring bracelets work today. But it also raises further questions. For instance, once there is no need for a criminal justice system, one of the central functions of the state has been eliminated. This is one of the social changes underlying the political anarchism that is a central feature of the Culture. There is, however, a more fundamental postulate. The core feature of Banks’s universe is that he imagines a scenario in which technological development has freed culture from all functional constraints – and thus, he imagines a situation in which culture has become purely memetic. This is perhaps the most important idea in his work, but it requires some unpacking. (...)

Societies with strong institutions become wealthier, more powerful militarily, or some combination of the two. These are the ones whose culture reproduces, either because it is imitated, or because it is imposed on others. And yet the dominant trend in human societies, over the past century, has been significant convergence with respect to institutional structure. Most importantly, there has been practically universal acceptance of the need for a market economy and a bureaucratic state as the only desirable social structure at the national level. One can think of this as the basic blueprint of a “successful” society. This has led to an incredible narrowing of cultural possibilities, as cultures that are functionally incompatible with capitalism or bureaucracy are slowly extinguished.

This winnowing down of cultural possibilities is what constitutes the trend that is often falsely described as “Westernization.” Much of it is actually just a process of adaptation that any society must undergo, in order to bring its culture into alignment with the functional requirements of capitalism and bureaucracy. It is not that other cultures are becoming more “Western,” it is that all cultures, including Western ones, are converging around a small number of variants."

Labels:

Business,

Culture,

Media,

Politics,

Psychology,

Relationships,

Technology

Nvidia Is Powering the A.I. Revolution

The revelation that ChatGPT, the astonishing artificial-intelligence chatbot, had been trained on an Nvidia supercomputer spurred one of the largest single-day gains in stock-market history. When the Nasdaq opened on May 25, 2023, Nvidia’s value increased by about two hundred billion dollars. A few months earlier, Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s C.E.O., had informed investors that Nvidia had sold similar supercomputers to fifty of America’s hundred largest companies. By the close of trading, Nvidia was the sixth most valuable corporation on earth, worth more than Walmart and ExxonMobil combined. Huang’s business position can be compared to that of Samuel Brannan, the celebrated vender of prospecting supplies in San Francisco in the late eighteen-forties. “There’s a war going on out there in A.I., and Nvidia is the only arms dealer,” one Wall Street analyst said.

Huang is a patient monopolist. He drafted the paperwork for Nvidia with two other people at a Denny’s restaurant in San Jose, California, in 1993, and has run it ever since. At sixty, he is sarcastic and self-deprecating, with a Teddy-bear face and wispy gray hair. Nvidia’s main product is its graphics-processing unit, a circuit board with a powerful microchip at its core. In the beginning, Nvidia sold these G.P.U.s to video gamers, but in 2006 Huang began marketing them to the supercomputing community as well. Then, in 2013, on the basis of promising research from the academic computer-science community, Huang bet Nvidia’s future on artificial intelligence. A.I. had disappointed investors for decades, and Bryan Catanzaro, Nvidia’s lead deep-learning researcher at the time, had doubts. “I didn’t want him to fall into the same trap that the A.I. industry has had in the past,” Catanzaro told me. “But, ten years plus down the road, he was right.”

In the near future, A.I. is projected to generate movies on demand, provide tutelage to children, and teach cars to drive themselves. All of these advances will occur on Nvidia G.P.U.s, and Huang’s stake in the company is now worth more than forty billion dollars.