It's usually understood that time wasted is art wasted. To edit down to the lean core, that’s often considered in most mediums the mark of quality (or, perhaps more accurately, and sometimes to a fault, professionalism). Historically, that’s been part of the cultural stigma against video games: not only is wasted time a given, it’s an integral part of the experience. Interactivity inverts the responsibility for moving the plot forward from storyteller to audience. A linear, self-propulsive story squanders the medium’s artistic potential. In games, the tension comes from not only the uncertainty about how the plot will resolve but also whether it even can. When the player fails, the story ends without ever having reached a conclusion. The work necessarily has to reset in some manner. Which creates a minor paradox: How can time discarded not also be time wasted? Isn’t this all noise and nonsense for the purpose of keeping a couch potato on the couch so long they sprout roots?

Repetition is usually dramatic poison, and it’s no wonder such failing without finality is erased from representations of gaming in other media. Whether in 1982’s Tron, or the “First Person Shooter” episode of The X-Files, or Gerard Butler’s turn in 2009’s Gamer, the “if you die in the game, you die for real” trope is understandable. Games can be complex, multifaceted cultural objects and are more frequently being covered that way, yet the accusation that games are action for the sake of action with little consequence or meaning is uncomfortably accurate much of the time. The source of the stigma stems from the early arcade days, when games primarily leveraged failure: every loss shook down the player for another quarter to send rattling into the machine. To beat the game and see it in its entirety took a mountain of coins, dedication, and skill—rendering play play, which is to say, largely divorced from narrative or the kinds of emotional experiences other art forms explored.

The pastime became less sport and more medium when home consoles and personal computers allowed games to experiment on a mass scale. Developers had no profit incentive to induce defeat once a cartridge or CD-ROM had been sold. Failure became instead the primary driver of tension within an emerging narrative, allowing story to flourish alongside gameplay from text adventures to action shooters. These stories were, save for those played with perfect skill, littered with loops. With every trap that fatally mangles a player in Tomb Raider, every police chase in Grand Theft Auto that ends in a brick wall instead of an escape, the narrative goes backward, the protagonist character’s story caught in a cyclical purgatory until the player-protagonist achieves a better result.

The sensation of breaking through those barriers is one of the most cathartic experiences that games offer, built on the interactivity that is so unique to gaming as a medium. Failure builds tension, which is then released with dramatic victory. But the accusation that these discarded loops are irrecuperable wastes of time still rings true, as modern game audiences have become comfortable consuming slop. In the past few years, games have trended toward becoming enormous blobs of content for the sake of content: an open world, a checklist of activities, a crafting system that turns environmental scrap into barely noticeable quality-of-life improvements. Ubisoft’s long-running Far Cry franchise has often been an example of this kind of format, as are survival crafting games like Funcom’s Conan Exiles or Bethesda’s overloaded wasteland sim Fallout 76. Every activity in a Far Cry or its ilk is a template activity that only comes to a finite end after many interminable engagements: a base is conquered, just to have three more highlighted. Failure here is a momentary punishment that can feel indistinguishable from success, as neither produces a sense of meaning or progress. These failure states are little moments of inattention and clumsy gameplay that lead only to repeating the same task better this time. Then when you do play better mechanically, you are rewarded with the privilege of repeating the same task, a tiny bit more interesting this time because the enemies are a little tougher in the next valley over. Within games that play for dozens of hours but are largely defined by mechanical combat loops that can last just seconds, everything can boil down to the present-tense experience so detrimentally that it’s hard to remember what you actually did at the end of those dozens of hours.

There is no narrative weight to liberating the same base in Far Cry across multiple attempts, no sense of cumulative progression to repeatedly coming at the same open-world content from different angles. There is only a grim resignation to the sunk-cost fallacy that, if you’ve already invested so much time into the damn thing already, you might as well bring it to some kind of resolution. Cranking up difficulty can make those present-tense moments more dramatic or stressful, but in the end it’s just adding more hours to the total playtime by adjusting the threshold for completing a given segment to a stricter standard. The game does not care if you succeed or fail, only that you spend time with it over its competitors.

As the industry creates limbos of success, the failure market itself has also mutated. See mobile gaming, a distorted echo of the coin-operated era, where players are behaviorally channeled to buy things like extra Poké Balls in Pokemon Go or “continue” permissions in Candy Crush and keep playing just a little longer. In 1980, failure cost a cumulative $2.8 billion in quarters; in 2022, the mobile games market made $124 billion by creating artificial barriers and choke points within their game mechanics, either making things more actively difficult or just slowing them down to prompt impulse spending.

In video games like the ubiquitous Fortnite or Blizzard’s recent Diablo 4, major releases often have “seasons” that heavily encourage cyclical spending. Every three months the game adds new content and asks the player to repeat the experience. The player exchanges between seven to twenty-five dollars to gild the stories they’ve already completed with extra objects, materials, and costumes—real money spent only for the privilege of sinking in the requisite time to acquire these virtual items, creating yet another loop of increasingly meaningless time usage. Fortnite came out in 2017. In 2023 the game generated all by itself a total $4.4 billion of income. A sum larger than the GDP of some countries, generated in one year, six years after release, off the impulse not to look like a scrub with no money in front of your friends even if those friends are dressed as Peter Griffin and the Xenomorph from Alien.

Besides its beautiful portrayal of a declining, melancholy world of perpetual autumn, what sets aside Elden Ring is its complexly layered difficulty. Elden Ring is quite eager to kill you, with a million ways to put a player down. But it is not meanly difficult, or insurmountably difficult. Most importantly, it is not difficult as part of a profit-seeking monetization loop. Instead, the failure states that are so often leveraged to extend playtime and coerce spending in most other games are here used as friction to build atmosphere. The constant starting again is exhausting, often stressful, sometimes infuriating. It is never meaningless, however: it confidently contradicts the worries of other mediums and the too-often-true accusations of slop with its deep understanding of how to create drama within any individual moment. Participating in its loops of death and rebirth as a player is to be fully within the Lands Between. Elden Ring presents a once-flourishing kingdom literally consumed by creeping nihilism and reflexive despair, which gives sympathetic resonance to the player’s determined and confident attempts to surmount these challenges. The most powerful or villainous enemies withdraw into themselves and let the world rot, while the weakest literally cower from the player, so exhausted by the idea of another painful death. Not the player, though: they exist in deliberate dramatic contrast to these characters by virtue of their own interactive participation with the world, making them the hero as both part of the text and as a meta-textual frame for the whole story.

By persisting in a world that trends downward, your own failures take on a defiant quality. The failure loop of the game incentivizes the player to loop again. This is where Elden Ring’s difficulty is particularly clever: because a player pays no consequence besides dropping experience points on the ground where they died, there is a hard limit on what the game can take away from them. There is an interactive choice and freedom even within these fail states, as you can abandon them or return again, fighting through all you had before; this in turn creates an incredible carrot-and-stick effect that, should you gamble on reclaiming your hard-won gains, doubles the stakes. While it is repeating the same content on the surface, there is a tangible and meaningful sense of cumulative progress and tactical variation on every death.

Once you’ve spent those points on an upgrade, that’s yours for the rest of the game—a permanent token of your dedication. A player is only ever risking the immediate next step, which adds weight to the fantasy of the gameplay, but not so much actual consequence that failure would crush a player’s spirit to continue. Holding onto your advancements even after dying and coming back makes your arc of progression stand in exciting contrast to the world around you. From a stagnant place, you are rising as something new, something vibrant. By incorporating these meta-textual elements into the mechanical play, there is a sense of individuality and ownership of the experience that more typical open-world check-listing games do not have. When I fail in Far Cry, it feels dramatically evaporative and impersonal. When I fail in Elden Ring, I feel like it’s because I made an active choice to risk something and I come back more engaged and determined than ever. (...)

The expansion’s price tag is less about monetizing the players than it is a reflection of the developmental effort involved. Elden Ring was certainly in a position to cash in at any time. The initial release was as successful as any game using more manipulative methods of extracting value. It was so popular that it sold twelve million copies in two weeks, moving on to over twenty million sold within a year of release. By any metric, but particularly by the metric where you multiply twenty million by the sixty-dollar retail price, the game was a massive success for art of any sort in any medium, doing so without relying on in-app purchases, artificial game resource scarcity, or making certain weapons and armor premium-purchase only.

For the health of video games as an artistic medium, this needs to be enough. That’s plenty of money. That’s such an enormous goddamn pile of money it even justifies the multimillion-dollar cost of developing modern flagship titles. Perhaps the problem with Elden Ring as an example is that it’s a masterpiece. It captured the imagination of millions. Games as an industry, instead of an artistic medium, don’t want that kind of success for only the games that are worthy of it. The industry needs to make money like that on the games built without subtlety, or craft, or heart. The industry needs to pull a profit off the slop too, and there is nothing they won’t gut or sell out to do it. If the old way was to tax failure, the new way is to dilute success, to treadmill the experience such that it never reaches a destination. (...)

This is just the era we live in, our own stagnant age in the Lands Between. With Disney and its subsidiaries sucking all of the air out of the room to repackage the same concept over and over, Hollywood has reached the stale conclusion that the same story can be told repetitively. The embrace of AI across multiple mediums just intensifies this dilution of what feels meaningful.

by Noah Caldwell-Gervais, The Baffler | Read more:

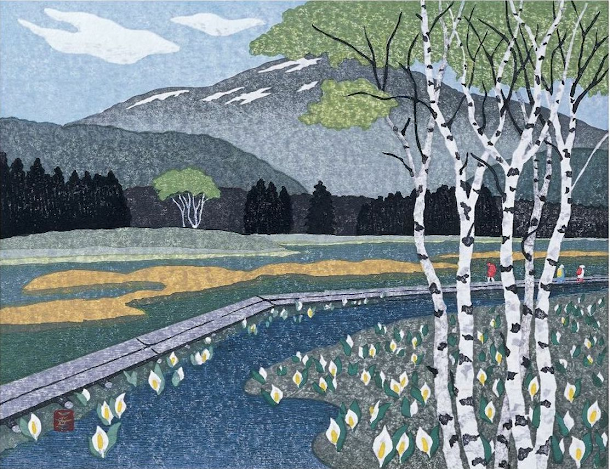

Image: From Elden Ring.|Bandi Namco

The sensation of breaking through those barriers is one of the most cathartic experiences that games offer, built on the interactivity that is so unique to gaming as a medium. Failure builds tension, which is then released with dramatic victory. But the accusation that these discarded loops are irrecuperable wastes of time still rings true, as modern game audiences have become comfortable consuming slop. In the past few years, games have trended toward becoming enormous blobs of content for the sake of content: an open world, a checklist of activities, a crafting system that turns environmental scrap into barely noticeable quality-of-life improvements. Ubisoft’s long-running Far Cry franchise has often been an example of this kind of format, as are survival crafting games like Funcom’s Conan Exiles or Bethesda’s overloaded wasteland sim Fallout 76. Every activity in a Far Cry or its ilk is a template activity that only comes to a finite end after many interminable engagements: a base is conquered, just to have three more highlighted. Failure here is a momentary punishment that can feel indistinguishable from success, as neither produces a sense of meaning or progress. These failure states are little moments of inattention and clumsy gameplay that lead only to repeating the same task better this time. Then when you do play better mechanically, you are rewarded with the privilege of repeating the same task, a tiny bit more interesting this time because the enemies are a little tougher in the next valley over. Within games that play for dozens of hours but are largely defined by mechanical combat loops that can last just seconds, everything can boil down to the present-tense experience so detrimentally that it’s hard to remember what you actually did at the end of those dozens of hours.

There is no narrative weight to liberating the same base in Far Cry across multiple attempts, no sense of cumulative progression to repeatedly coming at the same open-world content from different angles. There is only a grim resignation to the sunk-cost fallacy that, if you’ve already invested so much time into the damn thing already, you might as well bring it to some kind of resolution. Cranking up difficulty can make those present-tense moments more dramatic or stressful, but in the end it’s just adding more hours to the total playtime by adjusting the threshold for completing a given segment to a stricter standard. The game does not care if you succeed or fail, only that you spend time with it over its competitors.

As the industry creates limbos of success, the failure market itself has also mutated. See mobile gaming, a distorted echo of the coin-operated era, where players are behaviorally channeled to buy things like extra Poké Balls in Pokemon Go or “continue” permissions in Candy Crush and keep playing just a little longer. In 1980, failure cost a cumulative $2.8 billion in quarters; in 2022, the mobile games market made $124 billion by creating artificial barriers and choke points within their game mechanics, either making things more actively difficult or just slowing them down to prompt impulse spending.

In video games like the ubiquitous Fortnite or Blizzard’s recent Diablo 4, major releases often have “seasons” that heavily encourage cyclical spending. Every three months the game adds new content and asks the player to repeat the experience. The player exchanges between seven to twenty-five dollars to gild the stories they’ve already completed with extra objects, materials, and costumes—real money spent only for the privilege of sinking in the requisite time to acquire these virtual items, creating yet another loop of increasingly meaningless time usage. Fortnite came out in 2017. In 2023 the game generated all by itself a total $4.4 billion of income. A sum larger than the GDP of some countries, generated in one year, six years after release, off the impulse not to look like a scrub with no money in front of your friends even if those friends are dressed as Peter Griffin and the Xenomorph from Alien.

---

“Live service” is used to describe these games that attempt to stay evergreen with seasonal systems and intermittent small content drops. These seasonal titles and mobile cash shops have created feedback loops and cyclical repetitions that, by design, do not resolve. In recent years, however, there has been a counterreaction that tries to integrate these consumerist tendencies in the pursuit of something greater. (...)Besides its beautiful portrayal of a declining, melancholy world of perpetual autumn, what sets aside Elden Ring is its complexly layered difficulty. Elden Ring is quite eager to kill you, with a million ways to put a player down. But it is not meanly difficult, or insurmountably difficult. Most importantly, it is not difficult as part of a profit-seeking monetization loop. Instead, the failure states that are so often leveraged to extend playtime and coerce spending in most other games are here used as friction to build atmosphere. The constant starting again is exhausting, often stressful, sometimes infuriating. It is never meaningless, however: it confidently contradicts the worries of other mediums and the too-often-true accusations of slop with its deep understanding of how to create drama within any individual moment. Participating in its loops of death and rebirth as a player is to be fully within the Lands Between. Elden Ring presents a once-flourishing kingdom literally consumed by creeping nihilism and reflexive despair, which gives sympathetic resonance to the player’s determined and confident attempts to surmount these challenges. The most powerful or villainous enemies withdraw into themselves and let the world rot, while the weakest literally cower from the player, so exhausted by the idea of another painful death. Not the player, though: they exist in deliberate dramatic contrast to these characters by virtue of their own interactive participation with the world, making them the hero as both part of the text and as a meta-textual frame for the whole story.

By persisting in a world that trends downward, your own failures take on a defiant quality. The failure loop of the game incentivizes the player to loop again. This is where Elden Ring’s difficulty is particularly clever: because a player pays no consequence besides dropping experience points on the ground where they died, there is a hard limit on what the game can take away from them. There is an interactive choice and freedom even within these fail states, as you can abandon them or return again, fighting through all you had before; this in turn creates an incredible carrot-and-stick effect that, should you gamble on reclaiming your hard-won gains, doubles the stakes. While it is repeating the same content on the surface, there is a tangible and meaningful sense of cumulative progress and tactical variation on every death.

Once you’ve spent those points on an upgrade, that’s yours for the rest of the game—a permanent token of your dedication. A player is only ever risking the immediate next step, which adds weight to the fantasy of the gameplay, but not so much actual consequence that failure would crush a player’s spirit to continue. Holding onto your advancements even after dying and coming back makes your arc of progression stand in exciting contrast to the world around you. From a stagnant place, you are rising as something new, something vibrant. By incorporating these meta-textual elements into the mechanical play, there is a sense of individuality and ownership of the experience that more typical open-world check-listing games do not have. When I fail in Far Cry, it feels dramatically evaporative and impersonal. When I fail in Elden Ring, I feel like it’s because I made an active choice to risk something and I come back more engaged and determined than ever. (...)

The expansion’s price tag is less about monetizing the players than it is a reflection of the developmental effort involved. Elden Ring was certainly in a position to cash in at any time. The initial release was as successful as any game using more manipulative methods of extracting value. It was so popular that it sold twelve million copies in two weeks, moving on to over twenty million sold within a year of release. By any metric, but particularly by the metric where you multiply twenty million by the sixty-dollar retail price, the game was a massive success for art of any sort in any medium, doing so without relying on in-app purchases, artificial game resource scarcity, or making certain weapons and armor premium-purchase only.

For the health of video games as an artistic medium, this needs to be enough. That’s plenty of money. That’s such an enormous goddamn pile of money it even justifies the multimillion-dollar cost of developing modern flagship titles. Perhaps the problem with Elden Ring as an example is that it’s a masterpiece. It captured the imagination of millions. Games as an industry, instead of an artistic medium, don’t want that kind of success for only the games that are worthy of it. The industry needs to make money like that on the games built without subtlety, or craft, or heart. The industry needs to pull a profit off the slop too, and there is nothing they won’t gut or sell out to do it. If the old way was to tax failure, the new way is to dilute success, to treadmill the experience such that it never reaches a destination. (...)

This is just the era we live in, our own stagnant age in the Lands Between. With Disney and its subsidiaries sucking all of the air out of the room to repackage the same concept over and over, Hollywood has reached the stale conclusion that the same story can be told repetitively. The embrace of AI across multiple mediums just intensifies this dilution of what feels meaningful.

by Noah Caldwell-Gervais, The Baffler | Read more:

Image: From Elden Ring.|Bandi Namco