Tuesday, February 11, 2025

Golf of America

via:

[ed. DumbAss Bay is located near Palm Beach, Florida in case you were wondering. But hey, credit where credit is due, this is advertising genius. Sounds like Golf of America! Greenland next. But, after that, what? Gaza sounds too much like someone trying to hack a ball out of deep rough (or that feeling in your bowels you sometimes get after a chili dog and beer at the turn). Panama? 50 mile water hazard.]

Monday, February 10, 2025

Woke Beans

My cousin is known for making chili. And he's good at it. He makes his own chili flakes from his "secret combination" of various dried chilies, it has a very nice kick. It's like the perfect amount of spice, it's hot but not too hot. He also always adds kidney beans. Not canned beans either.

Anyways for the past 2 or 3 years by Cousin has become obsessed with all this bullshit about what is or isn't "woke" and how "woke" things are the end of the world. He's always been a good dude so I don't know what his bag is but he is completely obsessed. It's annoying.

Anyways for the past 2 or 3 years by Cousin has become obsessed with all this bullshit about what is or isn't "woke" and how "woke" things are the end of the world. He's always been a good dude so I don't know what his bag is but he is completely obsessed. It's annoying.

So the other weekend I was at his place and he was making his famous chili. So I got the idea for a little prank. I was like "I'm surprised you still put beans in your chili." He was like "What? Why?" I was like "Beans in chili are so woke. Everyone is saying so." He was like "What do you mean?" And he was like genuinely concerned. As if this was something serious. I said something like "Yeah beans in chili are woke, the original conservative Texans who made chili only used meat and chili. San Francisco liberals started adding beans to chili in the 60's because so many hippies were vegetarian. Now all the woke scientists are saying beans are a better protein source than meat." He didn't say anything to that.

I kind of just assumed he'd know I was fucking with him and get the joke. We have always fucked around with each other and jokes about and all. But he was quiet all dinner.

Just yesterday I was back again at his place and he was making his chili again. There were no beans. It was a totally different chili. This guy has been making his chili with beans for like 15 years. I was like, whats up? "Where's the beans?"

He was like "I don't fuck with that woke shit." I was like "What?" He was like "Beans in chili are woke. Even you know that."

Everyone else was like what? Because....what? I was like dude I was just fucking with you. He got REALLY angry. He dumped his chili in the sink and told everyone to go home. I thought he was pranking me back or something but he was serious. The dude totally lost it.

He texted me later and said this exact thing: "I researched this online and it turns out u really were lying to me, beans r not woke. How could u do this?"

We went back and forth for a bit. His position is even though we have historically pranked each other I went "too far", that I "betrayed him", that I "made him question his chili". I tried to ask him if this at all made him think he cared too much about "woke", like what if beans in chili WAS woke, so what? He ignored that and demanded I apologize.

I kind of just assumed he'd know I was fucking with him and get the joke. We have always fucked around with each other and jokes about and all. But he was quiet all dinner.

Just yesterday I was back again at his place and he was making his chili again. There were no beans. It was a totally different chili. This guy has been making his chili with beans for like 15 years. I was like, whats up? "Where's the beans?"

He was like "I don't fuck with that woke shit." I was like "What?" He was like "Beans in chili are woke. Even you know that."

Everyone else was like what? Because....what? I was like dude I was just fucking with you. He got REALLY angry. He dumped his chili in the sink and told everyone to go home. I thought he was pranking me back or something but he was serious. The dude totally lost it.

He texted me later and said this exact thing: "I researched this online and it turns out u really were lying to me, beans r not woke. How could u do this?"

We went back and forth for a bit. His position is even though we have historically pranked each other I went "too far", that I "betrayed him", that I "made him question his chili". I tried to ask him if this at all made him think he cared too much about "woke", like what if beans in chili WAS woke, so what? He ignored that and demanded I apologize.

Image: via

The U.S. Military’s Recruiting Crisis

The ranks of the American armed forces are depleted. Is the problem the military or the country?

At Fort Jackson, in South Carolina, the U.S. Army comes face to face with America’s youth. One recent morning, at the Future Soldiers training course, hundreds of overweight young men and women hoping to join the service lined up to run and perform calisthenics before a cordon of drill sergeants. Some were participating in organized workouts for the first time. Many heaved for breath when asked to run a half mile; others gave up and walked. A number hobbled around on crutches. At a weekly weigh-in, dozens of young men stood shirtless, revealing just how far they had to go.

When prospective recruits were asked to drop and do five pushups, many groaned and struggled, unable to complete the task. Some, their faces crimson, could barely hold themselves up.

“You thought you’d join the Army without being able to do a single pushup?” Staff Sergeant Kennedy Robinson barked at a recruit whose arms were twitching in agony.

“Yes, ma’am!” he said. To an extent that would have been hard to imagine a few years ago, he may have been right. (...)

President Trump insists that the decline in recruitment has a single cause: the Biden Administration’s efforts to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion programs chased away potential recruits. During last year’s campaign, he accused “woke generals” of being more concerned with advancing D.E.I. than with fighting wars. His Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth, a former member of the National Guard, has made similar accusations in dozens of appearances on Fox News. Hegseth’s book “The War on Warriors” is a protracted rant against what he describes as a progressive campaign to neuter the armed forces. “We are led by small generals and feeble officers without the courage to realize that, in the name of woke buzzwords, they are destroying our military,” he writes.

On the first day of his second term, Trump signed an executive order banning D.E.I. initiatives in the federal government. He also fired the head of the Coast Guard, Admiral Linda Lee Fagan, in part because she supported such programs. But many of the people charged with filling out the ranks of the U.S. military suggest that these moves will not reverse a trend decades in the making. Recruiters are contending with a population that’s not just unenthusiastic but incapable. According to a Pentagon study, more than three-quarters of Americans between the ages of seventeen and twenty-four are ineligible, because they are overweight, unable to pass the aptitude test, afflicted by physical or mental-health issues, or disqualified by such factors as a criminal record. While the political argument festers, military leaders are left to contemplate a broader problem: Can a country defend itself if not enough people are willing or able to fight? (...)

The U.S. Army’s recruiting station in Duluth, Georgia, north of Atlanta, has nine recruiters, and each aims to sign up one new recruit a month. It’s a modest goal, but they’ve met it each month for the past four years. “We try to seek out every eligible man and woman in the area—every single one,” the station’s leader, Sergeant First Class Stephen Supersad, told me.

The station has the advantage of a good location. Georgia lies within what the military sometimes calls the Southern Smile, a region, stretching from Arizona to Virginia, that supplies a disproportionate share of recruits. Duluth is also in an area with a large population of Korean Americans, many of them new arrivals or first-generation immigrants. The U.S. can expedite citizenship for green-card holders. The station sits next to a Korean restaurant, and has two Korean-speaking recruiters on staff.

During the day, potential recruits stream in, most of them from working- and middle-class families. When Misty Sanchez arrived, she didn’t immediately strike recruiters as a prime candidate; at eighteen years old, she wore braces and stood less than five feet tall. “Looking at me, you wouldn’t think I wanted to be a soldier,” she told me. But she had aced the entrance exam—and, like many other recruits, she had an older sibling in the service. Her sister Hilda had wanted to become a nurse, but their parents, who emigrated from Mexico, couldn’t afford to pay for college. She joined the Army, trained as a combat medic, and ultimately enrolled in nursing school at the military’s expense. Misty said that the experience had changed Hilda: “She used to be reserved and insecure. Now she’s confident. She takes pride in herself—her appearance even changed.” Misty hoped to make the same transformation. “I want the discipline,” she said. “I want to be tested physically and intellectually.” (...)

One of the students in Joseph’s class, whom I’ll call Rosa, arrived in the U.S. from Guatemala in 2022, after leaving her grandparents to join her long-estranged mother in Atlanta. Rosa travelled north some twelve hundred miles, on foot and by bus, paying smugglers and eluding predators. At the Texas border, she waded across the Rio Grande. When she arrived at Norcross High School, she spoke no English. Frank Cook, a retired lieutenant colonel who oversees J.R.O.T.C. programs in the area, told me that Rosa is his most impressive cadet. “She’s a star—her character, her intelligence, her leadership,” he said.

As an undocumented immigrant, Rosa is ineligible to join the armed forces, but she was clear about her aspirations. “I’m hoping to change my circumstances,” she told me. (...)

When I met Thorn, she still had a pound to lose and only a few more days to lose it. She was nervous but confident. “I’m so excited to be in the Army—I want the discipline,” she said. “I’ve only been here for three months, and I’m a changed person.”

For the Army, the appeal of a recruit like Thorn seemed obvious: she was smart, curious, and motivated. The only evidence of her previous weight was excess folds of skin. “I plan to spend my career in the Army, defending this country,” she said. Three days later, she passed the test and headed off to boot camp. (...)

The U.S. military’s recruiting troubles came just as it was attempting a fundamental shift in its mission. For decades, the focus was on fighting off terrorists and insurgents. But since 2018, as one Pentagon document put it, the imperative has been “confronting revisionist powers—primarily Russia and China.”

The Russian Army has suffered grievous losses in its invasion of Ukraine, but it is still roughly the same size as the U.S. military. Russian soldiers stand face to face with American troops in places like Lithuania—a NATO ally that the United States is legally obliged to protect, despite Trump’s threats to let the Russians “do whatever the hell they want” to member states that don’t pay enough for defense.

But the greater concern is China, whose economic and military growth threaten to make it a “peer competitor” of a kind that the United States hasn’t had since the Cold War. China’s military is far larger than America’s, with more than two million members. And, as the U.S. hollowed out its industrial capacity, China expanded; its steel industry is the largest in the world. In war games simulating a conflict between the two nations, the United States usually loses. According to the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, an American research firm, the Air Force would run out of advanced long-range munitions in less than two weeks.

The most probable trigger for a war is Taiwan, a thriving democracy that China’s leaders consider a de-facto part of their country. Since 1950, the United States has supplied Taiwan with military aid but has kept security guarantees studiously ambiguous. In recent years, the calculus changed: in 2022, Biden pledged explicitly to defend Taiwan from attack. Last year, China launched a new type of amphibious troop carrier, which appears designed for a military assault of the island.

It’s hard to know what Trump would do if the Chinese made a move on Taiwan. One of his top officials, Under-Secretary of Defense Elbridge Colby, is known for hawkish views on China. But the island sits some seven thousand miles from the U.S. mainland, which sharply limits America’s options. As a senior official in the Biden White House told me, “It’s the tyranny of distance.”

Most observers believe that an invasion is not imminent; the risk of an all-out war with the U.S., potentially killing hundreds of thousands of people, is too great. The more likely scenario is that China strangles Taiwan with a blockade, a possibility that it has recently underscored with large-scale naval and air exercises. In such an event, the U.S. Navy could aid Taiwan by escorting commercial vessels in and out—but only for about a year, Michael O’Hanlon, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told me: “After that, the Navy would run out of ships.”

The Navy is perhaps the most undermanned branch of the American military. Since the Cold War, its force has shrunk from about five hundred and fifty surface ships to roughly half that. In 2020, Trump declared that he wanted to boost the number to three hundred and fifty. “We couldn’t do it,” Bryan Clark, a Navy veteran who leads the Hudson Institute’s Center for Defense Concepts and Technology, said. “We don’t have enough sailors.”

In March, the Navy announced that seventeen vessels from the Merchant Marine, which provides fuel and cargo to warships, were being taken out of service for prolonged maintenance. Almost forty per cent of America’s attack submarines, among the country’s most formidable weapons, are unable to sail, because the Navy cannot service them quickly enough. The problem, at least in part, is a lack of sailors; ships routinely go to sea without a full crew, and the tasks of maintenance and repairs often go undone. Pilots are also scarce; the shortfall is estimated at seven hundred in the Navy and as many as two thousand in the Air Force. Those they do have work furiously. “We are either deployed or preparing to deploy all the time,” Lieutenant Commander Briana Plohocky, a Navy F-18 pilot, told me.

China has a modestly larger Navy than the U.S. does, with about three hundred and seventy vessels. But its shipbuilding capacity is more than two hundred times greater—making it far more able to replace vessels lost in combat. In the U.S., just seven private shipbuilders make the Navy’s submarines, destroyers, and aircraft carriers. As recently as 1990, there were seventeen. One of those that remain is Huntington Ingalls Industries, which maintains enormous shipyards in Virginia and Mississippi. The yards require some thirty-six thousand people to keep up production, but, at wages negotiated with the Navy during the pandemic, it is difficult to find skilled employees who will stay for the long term, despite offers of free training. “We’re competing with Chick-fil-A for workers,” Jennifer Boykin, the president of one of H.I.I.’s shipyards, told me. (...)

Sam Williams, a former sergeant who worked as a recruiter during the Iraq War, told me, “My approach was ‘I don’t know if you’re tough enough to be a marine.’ ” Williams would show up at a high school in his dress uniform and pick out the most charismatic student. “I’d find the top dog and walk right up to him and look him in the eye and tell him I didn’t think he was good enough,” he said. “Once I got him, his friends usually joined as well.” Major General William Bowers, the head of Marine Corps recruiting, told me that this approach is designed to attract dedicated people. “It’s human nature—value is determined by its difficulty to attain,” he said.

For the rest of the services, the process of recruiting new members has become increasingly transactional. “I try to lay out a plan for them that’s tailored to what they want to do,” Mackenson Joseph, the Army recruiter, told me. “You want to open your own business six years from now? I can help you do that. You want to be a nurse? We can train you to be a nurse. And I can put money in your pocket right now.”

In the days of the draft, a typical recruit’s salary amounted to a tiny fraction of what an equivalent private-sector worker would earn. But years of congressionally mandated pay increases have nearly closed the gap. And the military offers benefits that are rarely seen in the private sector: sailors and soldiers can often have their housing and health care paid for, and can retire at half pay after twenty years, with continued medical care for them and their families. The military typically helps cover college tuition for soldiers, a benefit that, if unused, can be passed to a spouse. Those who live on base have access to affordable child care. Those who live off base can qualify for subsidized mortgages. In the weeks that I spent talking to prospective recruits, most mentioned the economic benefits, especially college tuition, as their principal motivation. “People don’t want to serve the country anymore,” Joseph told me. “It’s ‘What’s the military offering me?’ ”

Many first-time Army recruits, some of them as young as seventeen, can receive a signing bonus of fifty thousand dollars. In other branches, rarer skills command larger bonuses. Naval recruits with certain kinds of technical expertise can get a hundred thousand dollars in bonuses and loan forgiveness. Navy Captain Ken Roman—the commander of a squadron of nuclear-powered Ohio-class submarines, which patrol the world’s oceans for months at a stretch—re-upped in 2024, and expects to make two hundred thousand dollars in bonuses in the next four years. But he says that the money isn’t what kept him in. At forty-six, Roman could have long since retired and followed many of his former colleagues into the private sector. At sea, though, “I get to work with some of the smartest people in the country, and the work is dynamic and important. Plus, I’m not a cubicle guy.”

To keep the numbers steady, the military needs a minimum of about a hundred and fifty thousand recruits a year. As the Pentagon scrambles to attract and retain people, its costs have soared; personnel now accounts for as much as a third of the defense budget. Barring a major war, that budget is unlikely to grow markedly. In the last years of the Cold War, military spending represented about six per cent of the nation’s G.D.P.; last year, it amounted to about half that. “There really isn’t any chance that the services are going to get larger,” Bryan Clark said. “They need to figure out ways to make do with fewer people.”

The military is rapidly adopting drones, robotics, and other technologies to replace humans. For decades, Nimitz-class aircraft carriers maintained crews of more than five thousand; newer carriers just setting sail require about seven hundred fewer people. The Pentagon’s Replicator initiative seeks to deploy thousands of unmanned air- and seaborne vehicles. “A swarm of drones will not need a swarm of drone operators,” Mark Montgomery, a retired rear admiral and a senior fellow at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, told me.

The rapid automation of warfare—airborne and undersea drones, unmanned ships and planes, and weapons operated by artificial intelligence—suggests that the battlefield of the future may contain far fewer soldiers. But the systems that run this equipment will require highly trained specialists. So will the demands of what Montgomery calls “offensive cyber war”—that is, hacking enemies. “We need Python coders,” Montgomery told me. “Fat kids welcome!” Officials in the Navy recruit heavily at a handful of tech schools, including M.I.T., Georgia Tech, and Carnegie Mellon, to find students with the knowledge and the aptitude to carry out such demanding tasks as operating nuclear reactors on aircraft carriers. “No dumb kids in those jobs,” Montgomery said. “They need to be really smart, which means they will have a lot of other opportunities.”

At Fort Jackson, in South Carolina, the U.S. Army comes face to face with America’s youth. One recent morning, at the Future Soldiers training course, hundreds of overweight young men and women hoping to join the service lined up to run and perform calisthenics before a cordon of drill sergeants. Some were participating in organized workouts for the first time. Many heaved for breath when asked to run a half mile; others gave up and walked. A number hobbled around on crutches. At a weekly weigh-in, dozens of young men stood shirtless, revealing just how far they had to go.

When prospective recruits were asked to drop and do five pushups, many groaned and struggled, unable to complete the task. Some, their faces crimson, could barely hold themselves up.

“You thought you’d join the Army without being able to do a single pushup?” Staff Sergeant Kennedy Robinson barked at a recruit whose arms were twitching in agony.

“Yes, ma’am!” he said. To an extent that would have been hard to imagine a few years ago, he may have been right. (...)

At the end of the Second World War, the American military had twelve million active-duty members. It now has 1.3 million—even though the population has more than doubled, and women are now eligible for armed service. “The U.S. military has been shrinking for thirty years,” Lawrence Wilkerson, a former senior State Department official who leads a task force on the challenges facing the armed services, said. “But its global commitments haven’t changed.” The military operates out of bases in more than fifty countries, and routinely deploys Special Operations forces to about eighty. Now, Wilkerson said, “it’s not clear that the military is large enough anymore for America to uphold its promises.” (...)

President Trump insists that the decline in recruitment has a single cause: the Biden Administration’s efforts to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion programs chased away potential recruits. During last year’s campaign, he accused “woke generals” of being more concerned with advancing D.E.I. than with fighting wars. His Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth, a former member of the National Guard, has made similar accusations in dozens of appearances on Fox News. Hegseth’s book “The War on Warriors” is a protracted rant against what he describes as a progressive campaign to neuter the armed forces. “We are led by small generals and feeble officers without the courage to realize that, in the name of woke buzzwords, they are destroying our military,” he writes.

On the first day of his second term, Trump signed an executive order banning D.E.I. initiatives in the federal government. He also fired the head of the Coast Guard, Admiral Linda Lee Fagan, in part because she supported such programs. But many of the people charged with filling out the ranks of the U.S. military suggest that these moves will not reverse a trend decades in the making. Recruiters are contending with a population that’s not just unenthusiastic but incapable. According to a Pentagon study, more than three-quarters of Americans between the ages of seventeen and twenty-four are ineligible, because they are overweight, unable to pass the aptitude test, afflicted by physical or mental-health issues, or disqualified by such factors as a criminal record. While the political argument festers, military leaders are left to contemplate a broader problem: Can a country defend itself if not enough people are willing or able to fight? (...)

The U.S. Army’s recruiting station in Duluth, Georgia, north of Atlanta, has nine recruiters, and each aims to sign up one new recruit a month. It’s a modest goal, but they’ve met it each month for the past four years. “We try to seek out every eligible man and woman in the area—every single one,” the station’s leader, Sergeant First Class Stephen Supersad, told me.

The station has the advantage of a good location. Georgia lies within what the military sometimes calls the Southern Smile, a region, stretching from Arizona to Virginia, that supplies a disproportionate share of recruits. Duluth is also in an area with a large population of Korean Americans, many of them new arrivals or first-generation immigrants. The U.S. can expedite citizenship for green-card holders. The station sits next to a Korean restaurant, and has two Korean-speaking recruiters on staff.

During the day, potential recruits stream in, most of them from working- and middle-class families. When Misty Sanchez arrived, she didn’t immediately strike recruiters as a prime candidate; at eighteen years old, she wore braces and stood less than five feet tall. “Looking at me, you wouldn’t think I wanted to be a soldier,” she told me. But she had aced the entrance exam—and, like many other recruits, she had an older sibling in the service. Her sister Hilda had wanted to become a nurse, but their parents, who emigrated from Mexico, couldn’t afford to pay for college. She joined the Army, trained as a combat medic, and ultimately enrolled in nursing school at the military’s expense. Misty said that the experience had changed Hilda: “She used to be reserved and insecure. Now she’s confident. She takes pride in herself—her appearance even changed.” Misty hoped to make the same transformation. “I want the discipline,” she said. “I want to be tested physically and intellectually.” (...)

One of the students in Joseph’s class, whom I’ll call Rosa, arrived in the U.S. from Guatemala in 2022, after leaving her grandparents to join her long-estranged mother in Atlanta. Rosa travelled north some twelve hundred miles, on foot and by bus, paying smugglers and eluding predators. At the Texas border, she waded across the Rio Grande. When she arrived at Norcross High School, she spoke no English. Frank Cook, a retired lieutenant colonel who oversees J.R.O.T.C. programs in the area, told me that Rosa is his most impressive cadet. “She’s a star—her character, her intelligence, her leadership,” he said.

As an undocumented immigrant, Rosa is ineligible to join the armed forces, but she was clear about her aspirations. “I’m hoping to change my circumstances,” she told me. (...)

On the ground at Fort Jackson, though, the situation seemed more encouraging. One would-be recruit was Savannah Thorn, from Ringgold, Georgia. Two years ago, Thorn, then seventeen, visited an Army recruiting station weighing three hundred and five pounds. Thorn told me she was raised by her grandmother. Her father, a meth addict, was in prison for armed robbery, and her mother, who gave birth to her at the age of twenty, was unable to care for her. Thorn told me that she had struggled with weight her whole life. “I ate chips and played Call of Duty all day long,” she said. Then her best friend joined the Navy, and Thorn saw a way to escape. “I didn’t want the life that was in store for me, living paycheck to paycheck, stuck in the small-town life,” she said. When she arrived at the recruiting station, she said, she could barely climb a flight of stairs, and she was prediabetic. The recruiter told her to come back after she’d lost a hundred pounds. “He thought he’d never see me again,” she said. A year later, Thorn returned, having lost the weight—still too heavy by the Army’s standards but close enough to get into the class at Fort Jackson. (...)

When I met Thorn, she still had a pound to lose and only a few more days to lose it. She was nervous but confident. “I’m so excited to be in the Army—I want the discipline,” she said. “I’ve only been here for three months, and I’m a changed person.”

For the Army, the appeal of a recruit like Thorn seemed obvious: she was smart, curious, and motivated. The only evidence of her previous weight was excess folds of skin. “I plan to spend my career in the Army, defending this country,” she said. Three days later, she passed the test and headed off to boot camp. (...)

The U.S. military’s recruiting troubles came just as it was attempting a fundamental shift in its mission. For decades, the focus was on fighting off terrorists and insurgents. But since 2018, as one Pentagon document put it, the imperative has been “confronting revisionist powers—primarily Russia and China.”

The Russian Army has suffered grievous losses in its invasion of Ukraine, but it is still roughly the same size as the U.S. military. Russian soldiers stand face to face with American troops in places like Lithuania—a NATO ally that the United States is legally obliged to protect, despite Trump’s threats to let the Russians “do whatever the hell they want” to member states that don’t pay enough for defense.

But the greater concern is China, whose economic and military growth threaten to make it a “peer competitor” of a kind that the United States hasn’t had since the Cold War. China’s military is far larger than America’s, with more than two million members. And, as the U.S. hollowed out its industrial capacity, China expanded; its steel industry is the largest in the world. In war games simulating a conflict between the two nations, the United States usually loses. According to the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, an American research firm, the Air Force would run out of advanced long-range munitions in less than two weeks.

The most probable trigger for a war is Taiwan, a thriving democracy that China’s leaders consider a de-facto part of their country. Since 1950, the United States has supplied Taiwan with military aid but has kept security guarantees studiously ambiguous. In recent years, the calculus changed: in 2022, Biden pledged explicitly to defend Taiwan from attack. Last year, China launched a new type of amphibious troop carrier, which appears designed for a military assault of the island.

It’s hard to know what Trump would do if the Chinese made a move on Taiwan. One of his top officials, Under-Secretary of Defense Elbridge Colby, is known for hawkish views on China. But the island sits some seven thousand miles from the U.S. mainland, which sharply limits America’s options. As a senior official in the Biden White House told me, “It’s the tyranny of distance.”

Most observers believe that an invasion is not imminent; the risk of an all-out war with the U.S., potentially killing hundreds of thousands of people, is too great. The more likely scenario is that China strangles Taiwan with a blockade, a possibility that it has recently underscored with large-scale naval and air exercises. In such an event, the U.S. Navy could aid Taiwan by escorting commercial vessels in and out—but only for about a year, Michael O’Hanlon, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told me: “After that, the Navy would run out of ships.”

The Navy is perhaps the most undermanned branch of the American military. Since the Cold War, its force has shrunk from about five hundred and fifty surface ships to roughly half that. In 2020, Trump declared that he wanted to boost the number to three hundred and fifty. “We couldn’t do it,” Bryan Clark, a Navy veteran who leads the Hudson Institute’s Center for Defense Concepts and Technology, said. “We don’t have enough sailors.”

In March, the Navy announced that seventeen vessels from the Merchant Marine, which provides fuel and cargo to warships, were being taken out of service for prolonged maintenance. Almost forty per cent of America’s attack submarines, among the country’s most formidable weapons, are unable to sail, because the Navy cannot service them quickly enough. The problem, at least in part, is a lack of sailors; ships routinely go to sea without a full crew, and the tasks of maintenance and repairs often go undone. Pilots are also scarce; the shortfall is estimated at seven hundred in the Navy and as many as two thousand in the Air Force. Those they do have work furiously. “We are either deployed or preparing to deploy all the time,” Lieutenant Commander Briana Plohocky, a Navy F-18 pilot, told me.

China has a modestly larger Navy than the U.S. does, with about three hundred and seventy vessels. But its shipbuilding capacity is more than two hundred times greater—making it far more able to replace vessels lost in combat. In the U.S., just seven private shipbuilders make the Navy’s submarines, destroyers, and aircraft carriers. As recently as 1990, there were seventeen. One of those that remain is Huntington Ingalls Industries, which maintains enormous shipyards in Virginia and Mississippi. The yards require some thirty-six thousand people to keep up production, but, at wages negotiated with the Navy during the pandemic, it is difficult to find skilled employees who will stay for the long term, despite offers of free training. “We’re competing with Chick-fil-A for workers,” Jennifer Boykin, the president of one of H.I.I.’s shipyards, told me. (...)

The Marines, with just over two hundred thousand members, are the smallest of the armed services (aside from the tiny Space Force). And, like the Army and the Navy, they have fewer troops than they used to. But the Marines routinely meet their recruiting goals, even with an ethos of exclusivity (“the few, the proud”) predicated on pushing potential entrants away. The Marines’ boot camp is considerably longer than those of the other services and notoriously brutal. Recruiters boast about it.

Sam Williams, a former sergeant who worked as a recruiter during the Iraq War, told me, “My approach was ‘I don’t know if you’re tough enough to be a marine.’ ” Williams would show up at a high school in his dress uniform and pick out the most charismatic student. “I’d find the top dog and walk right up to him and look him in the eye and tell him I didn’t think he was good enough,” he said. “Once I got him, his friends usually joined as well.” Major General William Bowers, the head of Marine Corps recruiting, told me that this approach is designed to attract dedicated people. “It’s human nature—value is determined by its difficulty to attain,” he said.

For the rest of the services, the process of recruiting new members has become increasingly transactional. “I try to lay out a plan for them that’s tailored to what they want to do,” Mackenson Joseph, the Army recruiter, told me. “You want to open your own business six years from now? I can help you do that. You want to be a nurse? We can train you to be a nurse. And I can put money in your pocket right now.”

In the days of the draft, a typical recruit’s salary amounted to a tiny fraction of what an equivalent private-sector worker would earn. But years of congressionally mandated pay increases have nearly closed the gap. And the military offers benefits that are rarely seen in the private sector: sailors and soldiers can often have their housing and health care paid for, and can retire at half pay after twenty years, with continued medical care for them and their families. The military typically helps cover college tuition for soldiers, a benefit that, if unused, can be passed to a spouse. Those who live on base have access to affordable child care. Those who live off base can qualify for subsidized mortgages. In the weeks that I spent talking to prospective recruits, most mentioned the economic benefits, especially college tuition, as their principal motivation. “People don’t want to serve the country anymore,” Joseph told me. “It’s ‘What’s the military offering me?’ ”

Many first-time Army recruits, some of them as young as seventeen, can receive a signing bonus of fifty thousand dollars. In other branches, rarer skills command larger bonuses. Naval recruits with certain kinds of technical expertise can get a hundred thousand dollars in bonuses and loan forgiveness. Navy Captain Ken Roman—the commander of a squadron of nuclear-powered Ohio-class submarines, which patrol the world’s oceans for months at a stretch—re-upped in 2024, and expects to make two hundred thousand dollars in bonuses in the next four years. But he says that the money isn’t what kept him in. At forty-six, Roman could have long since retired and followed many of his former colleagues into the private sector. At sea, though, “I get to work with some of the smartest people in the country, and the work is dynamic and important. Plus, I’m not a cubicle guy.”

To keep the numbers steady, the military needs a minimum of about a hundred and fifty thousand recruits a year. As the Pentagon scrambles to attract and retain people, its costs have soared; personnel now accounts for as much as a third of the defense budget. Barring a major war, that budget is unlikely to grow markedly. In the last years of the Cold War, military spending represented about six per cent of the nation’s G.D.P.; last year, it amounted to about half that. “There really isn’t any chance that the services are going to get larger,” Bryan Clark said. “They need to figure out ways to make do with fewer people.”

The military is rapidly adopting drones, robotics, and other technologies to replace humans. For decades, Nimitz-class aircraft carriers maintained crews of more than five thousand; newer carriers just setting sail require about seven hundred fewer people. The Pentagon’s Replicator initiative seeks to deploy thousands of unmanned air- and seaborne vehicles. “A swarm of drones will not need a swarm of drone operators,” Mark Montgomery, a retired rear admiral and a senior fellow at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies, told me.

The rapid automation of warfare—airborne and undersea drones, unmanned ships and planes, and weapons operated by artificial intelligence—suggests that the battlefield of the future may contain far fewer soldiers. But the systems that run this equipment will require highly trained specialists. So will the demands of what Montgomery calls “offensive cyber war”—that is, hacking enemies. “We need Python coders,” Montgomery told me. “Fat kids welcome!” Officials in the Navy recruit heavily at a handful of tech schools, including M.I.T., Georgia Tech, and Carnegie Mellon, to find students with the knowledge and the aptitude to carry out such demanding tasks as operating nuclear reactors on aircraft carriers. “No dumb kids in those jobs,” Montgomery said. “They need to be really smart, which means they will have a lot of other opportunities.”

by Dexter Filkins, New Yorker | Read more:

Image: Rebecca Kiger for The New YorkerSunday, February 9, 2025

Truth Distortions: A Mirror Doesn’t Lie

A mirror returns exactly what stands before it. No amount of wealth can bribe it, no volume of threats can intimidate it, no technological innovation can reprogram it. A billionaire’s reflection shows the same unaltered truth as a beggar’s. This fundamental democracy of reflection—this absolute fidelity to physical reality—makes mirrors uniquely immune to power. They are perhaps the last truly incorruptible witnesses in an age where truth itself has become negotiable.

Consider how people respond when confronted with an unflattering reflection. Some might adjust their appearance, accepting the mirror’s feedback as useful information. Others might avoid mirrors entirely, preferring not to face what they show. Still others, in moments of particular desperation, might smash the mirror itself—as if destroying the instrument of truth-telling could somehow alter the reality it reflects. But of course, breaking a mirror doesn’t change one’s appearance. It only ensures you’ll no longer have to look at it.

This relationship between truth and power lies at the heart of our current political crisis. We watch as wealthy and powerful figures attempt to rewrite reality itself, behaving as if sufficient money or influence can alter even physical law. When Elon Musk claims he can simultaneously run half a dozen major companies while reorganizing the federal government, he’s essentially asserting the power to create a twenty-fifth hour in the day. When Donald Trump declares that law doesn’t constrain his authority, he’s claiming the ability to rewrite the Constitution through sheer force of will. These are not just lies in the ordinary sense—they represent attempts to establish a world where truth itself is subject to negotiation, where reality becomes whatever those with power declare it to be.

There really is a sense in which we are truly living in Orwell’s nightmare. It didn’t come in the brutalist form of Oceania—at least not yet. It came in a more complex and unexpected way: censorship by attention overload. “Flooding the zone” to make truth impossible. The mirror we hold up to our collective civilization now is social media. And it lies to us.

Unlike a physical mirror, which stubbornly returns exactly what stands before it, our digital reflection has become infinitely malleable. Social media doesn’t just show us reality—it shows us a carefully curated, algorithmically enhanced version of ourselves and our world. The reflection changes based on who’s looking, morphing to confirm their existing beliefs and amplify their fears. This isn’t just distortion—it’s the destruction of the very concept of an objective reflection.

But we must also confront a deeper issue—the growing shamelessness of figures like Musk and Trump. People often describe their audacity as an absence of shame, but this misses the mark. Shame requires a shared standard, a common understanding of right and wrong, and a reality against which one’s actions can be measured. In a world where shared truth has disintegrated, that standard no longer exists. Without a common mirror to reflect reality, there’s nothing against which to compare behavior—no measure for judgment, no grounds for shame.

This is the most insidious consequence of truth’s erosion: it eliminates the very possibility of ethical accountability. If two plus two can equal five, then nothing—not corruption, not hypocrisy, not cruelty—can be definitively condemned. And when power operates unbound by truth, it becomes unbound by morality as well. Shamelessness is not a defect in such a world; it is a survival strategy, a natural adaptation to an environment where reality itself has become negotiable.

When Orwell imagined the Ministry of Truth, he envisioned bureaucrats manually editing newspapers and photographs, laboriously erasing people from history one image at a time. But our reality has proved more insidious. Instead of erasing truth, we’ve buried it under an avalanche of competing claims. Instead of forcing people to believe that two plus two equals five, we’ve created a world where every mathematical operation returns whatever result best serves power at that moment. The mirror hasn’t been broken—it’s been replaced by a screen that shows us whatever those controlling it want us to see.

What makes this particularly dangerous is who now controls these digital mirrors. Elon Musk’s acquisition of X (formerly Twitter) and Mark Zuckerberg’s sudden alignment with Trump aren’t just business decisions—they represent the consolidation of our collective reflection in the hands of those actively working to distort reality. (...)

This transformation of X into an “everything app” represents something more dangerous than just media consolidation—it’s an attempt to create a closed ecosystem where truth itself becomes proprietary. When Musk throttles links to external sources while promoting content from within X, he’s not just changing how news spreads—he’s working to make his platform the arbiter of reality itself. [ed. Fox "News" anyone?]

The merger of social media and financial services through X Money isn’t just another business expansion—it represents something far more dangerous: the fusion of narrative control with economic power. Consider what it means when the platform that shapes our understanding of reality also controls our ability to participate in economic life. This isn’t just a digital mirror anymore—it’s becoming a gatekeeper to both truth and commerce.

When Musk combines control over public discourse with payment processing, he’s creating unprecedented power to shape behavior. Imagine a world where your ability to transact financially becomes intertwined with your compliance with platform-approved narratives. The mirror isn’t just showing you what Musk wants you to see—it’s gaining the power to punish you for seeing anything else. (...)

The parallel to China’s WeChat is impossible to ignore. But there’s a crucial difference—WeChat’s fusion of social media and financial services operates under state oversight, however problematic that might be. X’s transformation represents something new: private control over both information and economic participation, accountable to neither democratic governance nor market competition.

Consider how people respond when confronted with an unflattering reflection. Some might adjust their appearance, accepting the mirror’s feedback as useful information. Others might avoid mirrors entirely, preferring not to face what they show. Still others, in moments of particular desperation, might smash the mirror itself—as if destroying the instrument of truth-telling could somehow alter the reality it reflects. But of course, breaking a mirror doesn’t change one’s appearance. It only ensures you’ll no longer have to look at it.

This relationship between truth and power lies at the heart of our current political crisis. We watch as wealthy and powerful figures attempt to rewrite reality itself, behaving as if sufficient money or influence can alter even physical law. When Elon Musk claims he can simultaneously run half a dozen major companies while reorganizing the federal government, he’s essentially asserting the power to create a twenty-fifth hour in the day. When Donald Trump declares that law doesn’t constrain his authority, he’s claiming the ability to rewrite the Constitution through sheer force of will. These are not just lies in the ordinary sense—they represent attempts to establish a world where truth itself is subject to negotiation, where reality becomes whatever those with power declare it to be.

There really is a sense in which we are truly living in Orwell’s nightmare. It didn’t come in the brutalist form of Oceania—at least not yet. It came in a more complex and unexpected way: censorship by attention overload. “Flooding the zone” to make truth impossible. The mirror we hold up to our collective civilization now is social media. And it lies to us.

Unlike a physical mirror, which stubbornly returns exactly what stands before it, our digital reflection has become infinitely malleable. Social media doesn’t just show us reality—it shows us a carefully curated, algorithmically enhanced version of ourselves and our world. The reflection changes based on who’s looking, morphing to confirm their existing beliefs and amplify their fears. This isn’t just distortion—it’s the destruction of the very concept of an objective reflection.

But we must also confront a deeper issue—the growing shamelessness of figures like Musk and Trump. People often describe their audacity as an absence of shame, but this misses the mark. Shame requires a shared standard, a common understanding of right and wrong, and a reality against which one’s actions can be measured. In a world where shared truth has disintegrated, that standard no longer exists. Without a common mirror to reflect reality, there’s nothing against which to compare behavior—no measure for judgment, no grounds for shame.

This is the most insidious consequence of truth’s erosion: it eliminates the very possibility of ethical accountability. If two plus two can equal five, then nothing—not corruption, not hypocrisy, not cruelty—can be definitively condemned. And when power operates unbound by truth, it becomes unbound by morality as well. Shamelessness is not a defect in such a world; it is a survival strategy, a natural adaptation to an environment where reality itself has become negotiable.

When Orwell imagined the Ministry of Truth, he envisioned bureaucrats manually editing newspapers and photographs, laboriously erasing people from history one image at a time. But our reality has proved more insidious. Instead of erasing truth, we’ve buried it under an avalanche of competing claims. Instead of forcing people to believe that two plus two equals five, we’ve created a world where every mathematical operation returns whatever result best serves power at that moment. The mirror hasn’t been broken—it’s been replaced by a screen that shows us whatever those controlling it want us to see.

What makes this particularly dangerous is who now controls these digital mirrors. Elon Musk’s acquisition of X (formerly Twitter) and Mark Zuckerberg’s sudden alignment with Trump aren’t just business decisions—they represent the consolidation of our collective reflection in the hands of those actively working to distort reality. (...)

This transformation of X into an “everything app” represents something more dangerous than just media consolidation—it’s an attempt to create a closed ecosystem where truth itself becomes proprietary. When Musk throttles links to external sources while promoting content from within X, he’s not just changing how news spreads—he’s working to make his platform the arbiter of reality itself. [ed. Fox "News" anyone?]

The merger of social media and financial services through X Money isn’t just another business expansion—it represents something far more dangerous: the fusion of narrative control with economic power. Consider what it means when the platform that shapes our understanding of reality also controls our ability to participate in economic life. This isn’t just a digital mirror anymore—it’s becoming a gatekeeper to both truth and commerce.

When Musk combines control over public discourse with payment processing, he’s creating unprecedented power to shape behavior. Imagine a world where your ability to transact financially becomes intertwined with your compliance with platform-approved narratives. The mirror isn’t just showing you what Musk wants you to see—it’s gaining the power to punish you for seeing anything else. (...)

The parallel to China’s WeChat is impossible to ignore. But there’s a crucial difference—WeChat’s fusion of social media and financial services operates under state oversight, however problematic that might be. X’s transformation represents something new: private control over both information and economic participation, accountable to neither democratic governance nor market competition.

by Mike Brock, TechDirt | Read more:

Image: City Museum Funhouse Mirrors via

[ed. Not familiar with X money, but if people want to entrust their savings to scammers like Musk and Trump, I'd say Go for It. Just don't whine about FDIC insurance when you can't get it back.]

Labels:

Critical Thought,

Government,

Media,

Politics,

Technology

Outrage of the Day - Feb. 9, 2025

MAGA’s Sickening Hypocrisy: From ‘Save The Children’ To ‘Defund The Org That Actually Saves Children’ (TechDirt); and, With Aid Cutoff, Trump Halts Agency’s Legacy of ‘Acting With Humanity’ (NYT):

Funds from the world’s richest nation once flowed from the largest global aid agency to an intricate network of small, medium and large organizations that delivered aid: H.I.V. medications for more than 20 million people; nutrition supplements for starving children; support for refugees, orphaned children and women battered by violence.

Now, that network is unraveling. (NYT)

After years of screaming “save the children” while baselessly accusing others of exploiting kids, the Trump administration is now trying to destroy the actual infrastructure that saves children. This one crosses from standard MAGA hypocrisy into genuinely evil territory.

I’m one of those people who doesn’t think you can (or should) call most people inherently “bad,” but if you support what the Trump administration is doing here, you are a bad person. (TD)

Funds from the world’s richest nation once flowed from the largest global aid agency to an intricate network of small, medium and large organizations that delivered aid: H.I.V. medications for more than 20 million people; nutrition supplements for starving children; support for refugees, orphaned children and women battered by violence.

Now, that network is unraveling. (NYT)

-----------

I’m one of those people who doesn’t think you can (or should) call most people inherently “bad,” but if you support what the Trump administration is doing here, you are a bad person. (TD)

------------

From Comments:

As one of the most important philosophers of the modern era once put it: “They’re all in favor of the unborn. They will do anything for the unborn. But once you’re born, you’re on your own. Pro-life conservatives are obsessed with the fetus from conception to nine months. After that, they don’t want to know about you. They don’t want to hear from you. No nothing. No neonatal care, no day care, no head start, no school lunch, no food stamps, no welfare, no nothing! If you’re preborn, you’re fine; if you’re preschool, you’re fucked!”

“The unborn” are a convenient group of people to advocate for. They never make demands of you; they are morally uncomplicated, unlike the incarcerated, addicted, or the chronically poor; they don’t resent your condescension or complain that you are not politically correct; unlike widows, they don’t ask you to question patriarchy; unlike orphans, they don’t need money, education, or childcare; unlike aliens, they don’t bring all that racial, cultural, and religious baggage that you dislike; they allow you to feel good about yourself without any work at creating or maintaining relationships; and when they are born, you can forget about them, because they cease to be unborn. It’s almost as if, by being born, they have died to you.

You can love the unborn and advocate for them without substantially challenging your own wealth, power, or privilege, without re-imagining social structures, apologizing, or making reparations to anyone. They are, in short, the perfect people to love if you want to claim you love Jesus but actually dislike people who breathe.

Prisoners? Immigrants? The sick? The poor? Widows? Orphans? All the groups that are specifically mentioned in the Bible? They all get thrown under the bus for the unborn.

— Dr. Dave Barnhart, Christian Minister

When the central pillar of your ideology is hating The Other and blaming them for all the wrongs (whether real or imagined) that you suffer there must always be an Other to vilify, and if the current one is no longer doing the trick then a new one will be found in short order.

And the best part is that a hate-focused ideology like this isn’t even safe for it’s members, because if ever there’s no-one outside the group that’ll make for an effective scapegoat and target for hate and blame? Why then it’s time for a little in-group ideological Othering…

***

You can love the unborn and advocate for them without substantially challenging your own wealth, power, or privilege, without re-imagining social structures, apologizing, or making reparations to anyone. They are, in short, the perfect people to love if you want to claim you love Jesus but actually dislike people who breathe.

Prisoners? Immigrants? The sick? The poor? Widows? Orphans? All the groups that are specifically mentioned in the Bible? They all get thrown under the bus for the unborn.

— Dr. Dave Barnhart, Christian Minister

***

And the best part is that a hate-focused ideology like this isn’t even safe for it’s members, because if ever there’s no-one outside the group that’ll make for an effective scapegoat and target for hate and blame? Why then it’s time for a little in-group ideological Othering…

***

[ed. I've always thought MAGA was largely a cult of personality thing, specific to Trump (with no obvious heir apparent). Now that Musk seems intent on out-Trumping Trump we have someone who's a hell of a lot smarter and more dangerous in a lot of ways (Trump being 78, and with obvious cognitive/personality issues). So that hope/theory may no longer be operable. It could and undoubtedly will get much worse.]

Labels:

Government,

Health,

history,

Politics,

Relationships,

Religion

Saturday, February 8, 2025

Surveillance Pricing Is Ripping You Off

It’s 5 a.m. and your toddler is crying. His forehead is hot. You remember, cursing yourself, that you are out of Tylenol. You squint at your phone and order more, selecting the quickest delivery option. Actually, that’s not soon enough. You pay the $2 fee so that it will arrive faster. Wait, where is the thermometer? Fine, order that too. You barely manage to complete the purchase before your kid throws up.

What if the retailer that sold you both of these items had raised their prices slightly, just for you, based on your previous shopping habits? Because it had access to data that pigeonholed you as a stressed-out parent who won’t notice that you’re being upcharged for medical supplies, especially at 5 a.m.? Because it could? This is known as surveillance pricing, and a recent study from the Federal Trade Commission suggests that it happens all the time.

To back up for a moment: Last July, the FTC asked eight large companies — including Mastercard, JPMorgan Chase, and Accenture — to turn over information about the data they collect on individual consumers and how it affects pricing. Investigators were particularly interested in middlemen hired by retailers to use algorithms to change and target prices for different markets — in other words, how they harness your personal information to determine whether (and when) they can charge you more. You know how Uber adjusts pricing based on location and demand? The FTC had reason to believe that companies were doing that with services and products they sold but microtargeted to customers based on their unique profiles — their age, their spending patterns, and even their tendency to order a specific thing at a certain time of night.

Late on January 17, in the final hours of the Biden administration, the FTC published the initial findings of its study, which was swiftly buried under an avalanche of Trump-related news. The report “revealed that details like a person’s precise location or browser history can be frequently used to target individual consumers with different prices for the same goods and services.” Then–FTC chair Lina Khan recommended that the FTC “continue to investigate surveillance pricing practices because Americans deserve to know how their private data is being used to set the prices they pay.”

Andrew N. Ferguson, Trump’s pick to replace Khan, dissented from the report, implying that the investigation will not continue. In the absence of concrete policy to oversee or regulate surveillance pricing, it can expand unchecked. That leaves normal consumers out here to fend for ourselves.

Corporate greed is not new, nor is it illegal. Retailers are always trying to charge the highest amount they can get away with — it’s the principle of supply and demand, and how they stay afloat. What is new, though, is the technology that retailers can use to predict what specific customers might be willing to pay and the opportunities to offer tailored pricing to individuals. (If you’re shopping online, how do you know if your price is different from another person’s? You don’t.) This is different from old-fashioned dynamic pricing — where prices go up or down for everyone depending on market demand — and much creepier.

If your bills continue to be all over the place, and you suspect that you’re getting ripped off simply because of your past shopping behavior, well — you’re not crazy. Here, policy experts share their advice on how to spot surveillance pricing and fight it when it happens.

What if the retailer that sold you both of these items had raised their prices slightly, just for you, based on your previous shopping habits? Because it had access to data that pigeonholed you as a stressed-out parent who won’t notice that you’re being upcharged for medical supplies, especially at 5 a.m.? Because it could? This is known as surveillance pricing, and a recent study from the Federal Trade Commission suggests that it happens all the time.

To back up for a moment: Last July, the FTC asked eight large companies — including Mastercard, JPMorgan Chase, and Accenture — to turn over information about the data they collect on individual consumers and how it affects pricing. Investigators were particularly interested in middlemen hired by retailers to use algorithms to change and target prices for different markets — in other words, how they harness your personal information to determine whether (and when) they can charge you more. You know how Uber adjusts pricing based on location and demand? The FTC had reason to believe that companies were doing that with services and products they sold but microtargeted to customers based on their unique profiles — their age, their spending patterns, and even their tendency to order a specific thing at a certain time of night.

Late on January 17, in the final hours of the Biden administration, the FTC published the initial findings of its study, which was swiftly buried under an avalanche of Trump-related news. The report “revealed that details like a person’s precise location or browser history can be frequently used to target individual consumers with different prices for the same goods and services.” Then–FTC chair Lina Khan recommended that the FTC “continue to investigate surveillance pricing practices because Americans deserve to know how their private data is being used to set the prices they pay.”

Andrew N. Ferguson, Trump’s pick to replace Khan, dissented from the report, implying that the investigation will not continue. In the absence of concrete policy to oversee or regulate surveillance pricing, it can expand unchecked. That leaves normal consumers out here to fend for ourselves.

Corporate greed is not new, nor is it illegal. Retailers are always trying to charge the highest amount they can get away with — it’s the principle of supply and demand, and how they stay afloat. What is new, though, is the technology that retailers can use to predict what specific customers might be willing to pay and the opportunities to offer tailored pricing to individuals. (If you’re shopping online, how do you know if your price is different from another person’s? You don’t.) This is different from old-fashioned dynamic pricing — where prices go up or down for everyone depending on market demand — and much creepier.

If your bills continue to be all over the place, and you suspect that you’re getting ripped off simply because of your past shopping behavior, well — you’re not crazy. Here, policy experts share their advice on how to spot surveillance pricing and fight it when it happens.

by Charlotte Cowles, The Cut | Read more:

Image: Photo-Illustration: by The Cut; Photos: Getty Images

Labels:

Business,

Economics,

Government,

Politics,

Technology

Scent Makes a Place

In the late spring, the desert smells like chocolate. It’s fleeting, and it isn’t everywhere in New Mexico, but sometimes, walking in the scrubland, it suddenly hits: a sweetness shimmering through the air. At first, I didn’t know how to read this olfactory information, but now I can look for the source: yellow-petaled flowers with dark centers—chocolate daisies—blooming in the sun.

The American Southwest smells unlike anywhere I’ve lived before. It’s better than the woods of Maine; it’s far more fragrant. I didn’t expect that when I moved here. I’m a perfume collector, so I had smelled the desert through art before I smelled it in person. Through my experience sampling “Mojave Ghost,” “Arizona,” and “Desert Eden”—perfumes designed to evoke cactus flowers and conifers—I thought the mesas would smell dusty and musky, with a little green cypress thrown in. I was wrong.

I could list each note that sung with the pine, laying it out beat by beat. That’s how perfume companies do it: They give you the top, middle, and base notes. Sometimes this information is provided right on the packaging, though one still must sniff the nozzle to understand how they all come together. Language can only offer a loose approximation of a perfume, and a perfume can only offer a loose approximation of a natural smellscape.

The airy scent that follows rain is known as petrichor, and there are many forms. The petrichor in Singapore, for example, will be quite different from that of Reykjavik. The desert smells most intensely after a sudden summer downpour, when the plants release their oils, when the soil opens its pores to the sky. Nevertheless, perfumers have identified a common essence to petrichor: the chemical compound geosmin. It takes its name from the Greek words for “earth” and “smell.” In small amounts—and we are able to detect very small amounts of geosmin, down to 10 parts per trillion, akin to a stick of incense diffused through the entire Empire State Building—it smells familiar and musty, a little minerally, a little dirty, but in a nice way. In larger doses, it can come across mildewy and rank, like dirty laundry left in a damp basement. In nature, geosmin is produced by certain species of blue-green algae that live within soil, and is part of the fragrance bouquet that gets released into the air before, during, and after the high desert gets hit by rain.

For perfumers, the discovery and naming of geosmin in the 1960s was a boon, although it did take several more years to perfect the lab-synthesized version of the compound. It can be used in perfumery to add a muddy, petrichor scent to the bouquet. Since most fragrance houses don’t release a list of their chemical compounds, it’s not always easy to know when you’re smelling geosmin, but if you’re looking for a desert-inspired smellscape, there’s a good chance that synthetic petrichor will be part of the mix. (...)

But there are other ways to get a rainy desert scent, according to Cebastien Rose and Robin Moore, perfumers at the Albuquerque-based company Drylands Wilds. Unlike most perfumers, they don’t use synthetic odor molecules; their ingredients are derived from locally foraged plants, and through their work, they’ve become experts in the various scentscapes of New Mexico. Including greasewood, which is often considered a pest plant, a garbage scrub that needs getting rid of but is also responsible for an earthy, fresh Southwestern scent that wafts from its leaves. “Right before it rains,” explains Rose, “it opens all its stomata.” These “tiny mouths” are how the plant breathes, and as the rain begins to fall, the leaves release aromatic organic compounds called cresols, which smell a bit like coal tar and—thanks in part to their association with rainfall—a lot like a drenched desert.

“We’re obsessed with trying to capture that exact experience of being out here, walking the hills, smelling the piñon resin when it gets hot, smelling the ponderosa bark that wafts the air with vanilla,” Rose says. But it’s not enough to simply extract oils from the bark. It’s even difficult to capture a single tree in perfume form, says Rose. Plus, that wouldn’t reflect the experience of walking under the “giant, orange-barked trees. You wouldn’t get the oak moss, the soil, the place.” That, explains Rose, is where the “art of perfumery” comes in. The Dryland Wilds ponderosa perfume has yellow nutsedge, sweet clover, piñon, oakmoss, fir, and ponderosa. It contains extracts that mimic the dirt, resulting in a liquid that smells like a tree, yes, but is also intended to smell like a moment—a dry summer afternoon on the Atalaya trails, for instance. “We’ve had people cry after smelling it,” adds Moore. “One woman had lived in a ponderosa tree trying to protect old growth forest for a year, and for her, that hit was instantaneous.” (...)

Smell, as a sense, is dependent on so many variables—it can be affected by our previous experience, our current context, and our emotional or mental state. Something may smell “good” in one scenario and disgusting in another. How we judge a smell can be changed by the sounds we’re hearing, the temperature that surrounds us, the food we’re tasting, the colors we’re seeing. It’s a sense that shifts and slips, sometimes in predictable ways but sometimes in totally unexpected directions. (...)

The American Southwest smells unlike anywhere I’ve lived before. It’s better than the woods of Maine; it’s far more fragrant. I didn’t expect that when I moved here. I’m a perfume collector, so I had smelled the desert through art before I smelled it in person. Through my experience sampling “Mojave Ghost,” “Arizona,” and “Desert Eden”—perfumes designed to evoke cactus flowers and conifers—I thought the mesas would smell dusty and musky, with a little green cypress thrown in. I was wrong.

Here, the plants hold their essences close to the stem out of necessity, only letting their oils free when it’s safe to do so, when they’re ready to be fertile. Here, the sand bakes under the sun and the fragile soil releases its secrets with each step. Here, even my dog’s urine is more potent, more fragrant on the wind, a louder yellow than I ever witnessed during our walks in Maine, blending uneasily with the grey rabbitbrush. It’s wetter and stranger than I ever anticipated—complex, elusive, fecund.

After a year in Santa Fe, I’ve finally started to scratch the surface of knowing this landscape. But the learning is slow and requires all my senses, including the one most often forgotten, what Hellen Keller called the “fallen angel” of the body. Unable to see or hear, smell became her primary way of reading the wider world; she lamented how that “most important” sense had been “neglected and disparaged” by the general populace, though she found it hard to communicate this knowledge to others. “It is difficult to put into words the thing itself,” she wrote. “There seems to be no adequate vocabulary of smells, and I must fall back on approximate phrase and metaphor.” (...)

After a year in Santa Fe, I’ve finally started to scratch the surface of knowing this landscape. But the learning is slow and requires all my senses, including the one most often forgotten, what Hellen Keller called the “fallen angel” of the body. Unable to see or hear, smell became her primary way of reading the wider world; she lamented how that “most important” sense had been “neglected and disparaged” by the general populace, though she found it hard to communicate this knowledge to others. “It is difficult to put into words the thing itself,” she wrote. “There seems to be no adequate vocabulary of smells, and I must fall back on approximate phrase and metaphor.” (...)

I could list each note that sung with the pine, laying it out beat by beat. That’s how perfume companies do it: They give you the top, middle, and base notes. Sometimes this information is provided right on the packaging, though one still must sniff the nozzle to understand how they all come together. Language can only offer a loose approximation of a perfume, and a perfume can only offer a loose approximation of a natural smellscape.

The airy scent that follows rain is known as petrichor, and there are many forms. The petrichor in Singapore, for example, will be quite different from that of Reykjavik. The desert smells most intensely after a sudden summer downpour, when the plants release their oils, when the soil opens its pores to the sky. Nevertheless, perfumers have identified a common essence to petrichor: the chemical compound geosmin. It takes its name from the Greek words for “earth” and “smell.” In small amounts—and we are able to detect very small amounts of geosmin, down to 10 parts per trillion, akin to a stick of incense diffused through the entire Empire State Building—it smells familiar and musty, a little minerally, a little dirty, but in a nice way. In larger doses, it can come across mildewy and rank, like dirty laundry left in a damp basement. In nature, geosmin is produced by certain species of blue-green algae that live within soil, and is part of the fragrance bouquet that gets released into the air before, during, and after the high desert gets hit by rain.

For perfumers, the discovery and naming of geosmin in the 1960s was a boon, although it did take several more years to perfect the lab-synthesized version of the compound. It can be used in perfumery to add a muddy, petrichor scent to the bouquet. Since most fragrance houses don’t release a list of their chemical compounds, it’s not always easy to know when you’re smelling geosmin, but if you’re looking for a desert-inspired smellscape, there’s a good chance that synthetic petrichor will be part of the mix. (...)

But there are other ways to get a rainy desert scent, according to Cebastien Rose and Robin Moore, perfumers at the Albuquerque-based company Drylands Wilds. Unlike most perfumers, they don’t use synthetic odor molecules; their ingredients are derived from locally foraged plants, and through their work, they’ve become experts in the various scentscapes of New Mexico. Including greasewood, which is often considered a pest plant, a garbage scrub that needs getting rid of but is also responsible for an earthy, fresh Southwestern scent that wafts from its leaves. “Right before it rains,” explains Rose, “it opens all its stomata.” These “tiny mouths” are how the plant breathes, and as the rain begins to fall, the leaves release aromatic organic compounds called cresols, which smell a bit like coal tar and—thanks in part to their association with rainfall—a lot like a drenched desert.

“We’re obsessed with trying to capture that exact experience of being out here, walking the hills, smelling the piñon resin when it gets hot, smelling the ponderosa bark that wafts the air with vanilla,” Rose says. But it’s not enough to simply extract oils from the bark. It’s even difficult to capture a single tree in perfume form, says Rose. Plus, that wouldn’t reflect the experience of walking under the “giant, orange-barked trees. You wouldn’t get the oak moss, the soil, the place.” That, explains Rose, is where the “art of perfumery” comes in. The Dryland Wilds ponderosa perfume has yellow nutsedge, sweet clover, piñon, oakmoss, fir, and ponderosa. It contains extracts that mimic the dirt, resulting in a liquid that smells like a tree, yes, but is also intended to smell like a moment—a dry summer afternoon on the Atalaya trails, for instance. “We’ve had people cry after smelling it,” adds Moore. “One woman had lived in a ponderosa tree trying to protect old growth forest for a year, and for her, that hit was instantaneous.” (...)

Smell, as a sense, is dependent on so many variables—it can be affected by our previous experience, our current context, and our emotional or mental state. Something may smell “good” in one scenario and disgusting in another. How we judge a smell can be changed by the sounds we’re hearing, the temperature that surrounds us, the food we’re tasting, the colors we’re seeing. It’s a sense that shifts and slips, sometimes in predictable ways but sometimes in totally unexpected directions. (...)

Each smell is a distinct sensation, but together they are more than that. Smellscapes are part of place-making, the process by which a site becomes imbued with meaning and metaphor; a place is more than just the physical location. Places have history, lore, memory, and emotion all infused into them, and encounters we have with a place are participatory.

by Katy Kelleher, Nautilus | Read more:

Image: Mike Hardiman/Shutterstock[ed. Greatly undervalued. Whenever I go back to Alaska I'm definitely aware of how unique the air smells - primal and earthy, sharp and fresh. Same with the lush tropical slopes high above Hawaii's beaches, early at sunrise. In terms of manufactured smells, a wisp of Eau de London or Hai Karate (!) (which I haven't experienced in decades) can take me back in an instant to my first girlfriend and high school... over 50 years ago. Powerful stuff.]

The Problem With Problem Sharks

The Problem With Problem Sharks (Nautilus)

Image: karelnoppe/Shutterstock

[ed. A few bad actors give all sharks a bad name. See also: First Evidence of Individual Sharks Involved in Multiple Predatory Bites on People (Society for Conservation Biology). Love this image.]

Image: karelnoppe/Shutterstock

[ed. A few bad actors give all sharks a bad name. See also: First Evidence of Individual Sharks Involved in Multiple Predatory Bites on People (Society for Conservation Biology). Love this image.]

Friday, February 7, 2025

There Is Way Too Much Serendipity

As we all know, sugar is sweet and so are the $30B in yearly revenue from the artificial sweetener industry.

Four billion years of evolution endowed our brains with a simple, straightforward mechanism to make sure we occasionally get an energy refuel so we can continue the foraging a little longer, and of course we are completely ignoring the instructions and spend billions on fake fuel that doesn’t actually grant any energy. A classic case of the Human Alignment Problem.

If we’re going to break our conditioning anyway, where do we start? How do you even come up with a new artificial sweetener? I’ve been wondering about this, because it’s not obvious to me how you would figure out what is sweet and what is not.

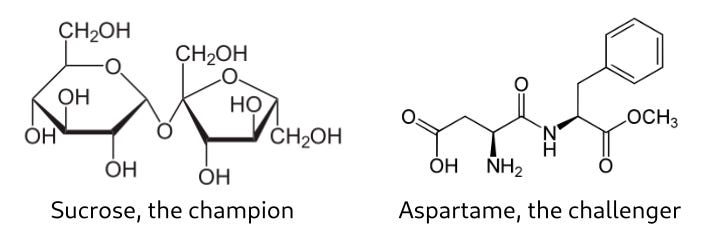

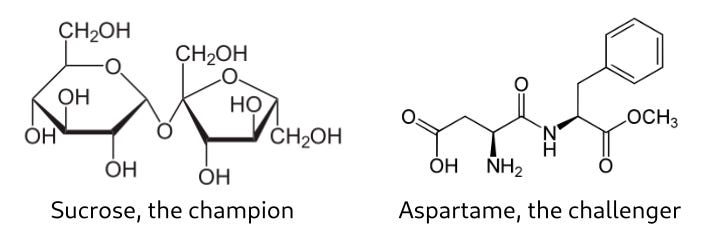

Look at sucrose and aspartame side by side:

I can’t imagine someone looking at these two molecules and thinking “surely they taste the same”. Most sweeteners were discovered in the 20th century, before high-throughput screening was available. So how did they proceed?

Let’s look into these molecules’ origin stories.

Aspartame was discovered accidentally by a chemist researching a completely unrelated topic. At some point, he licked his finger to grab a piece of paper and noticed a strong sweet taste.

Cyclamate was discovered by a grad student who put his cigarette on his bench, then smoked it again and noticed the cigarette was sweet.