“Appleseed” was a nickname; he was born as John Chapman. As a young man, Chapman became convinced that Christianity had lost its way and needed to be restored by a new church. He worked in an orchard, fell in love with apples, and devoted the rest of his long life to wandering through the newly occupied Middle West, passing out tracts for the new church — and establishing apple orchards, selling the saplings for a few pennies each.

Although a dozen or so Johnny Appleseed festivals are still celebrated, he is less likely to be found in children’s books today. That may be because historians realized that Appleseed was not just a kindly religious eccentric who went around planting apples so that Midwesterners could have fresh, healthy fruit. Instead, he was a vital part of village infrastructure: his apples were mostly not for eating, they were for making hard cider.

Typical hard cider has an alcohol level of about five percent, enough to kill most bacteria and viruses. Many settlers drank it whenever possible, because the water around them was polluted — sometimes by their own excrement, more commonly by excrement from their farm animals. Cider from Appleseed’s apples let people avoid smelly, foul-tasting water. It was a public health measure — one that, to be sure, let some of its users pass the day in a mild alcoholic haze.

For as long as our species has lived in settled communities, we have struggled to provide ourselves with water. If modern agriculture, the subject of the previous article in this series, is a story of innovation and progress, the water supply has all too often been the opposite: a tale of stagnation and apathy. Even today, about two billion people, most of them in poor, rural areas, do not have a reliable supply of clean water — potable water, in the jargon of water engineers. Bad water leads to the death every year of about a million people. In terms of its immediate impact on human lives, water is the world’s biggest environmental problem and its worst public health problem — as it has been for centuries.

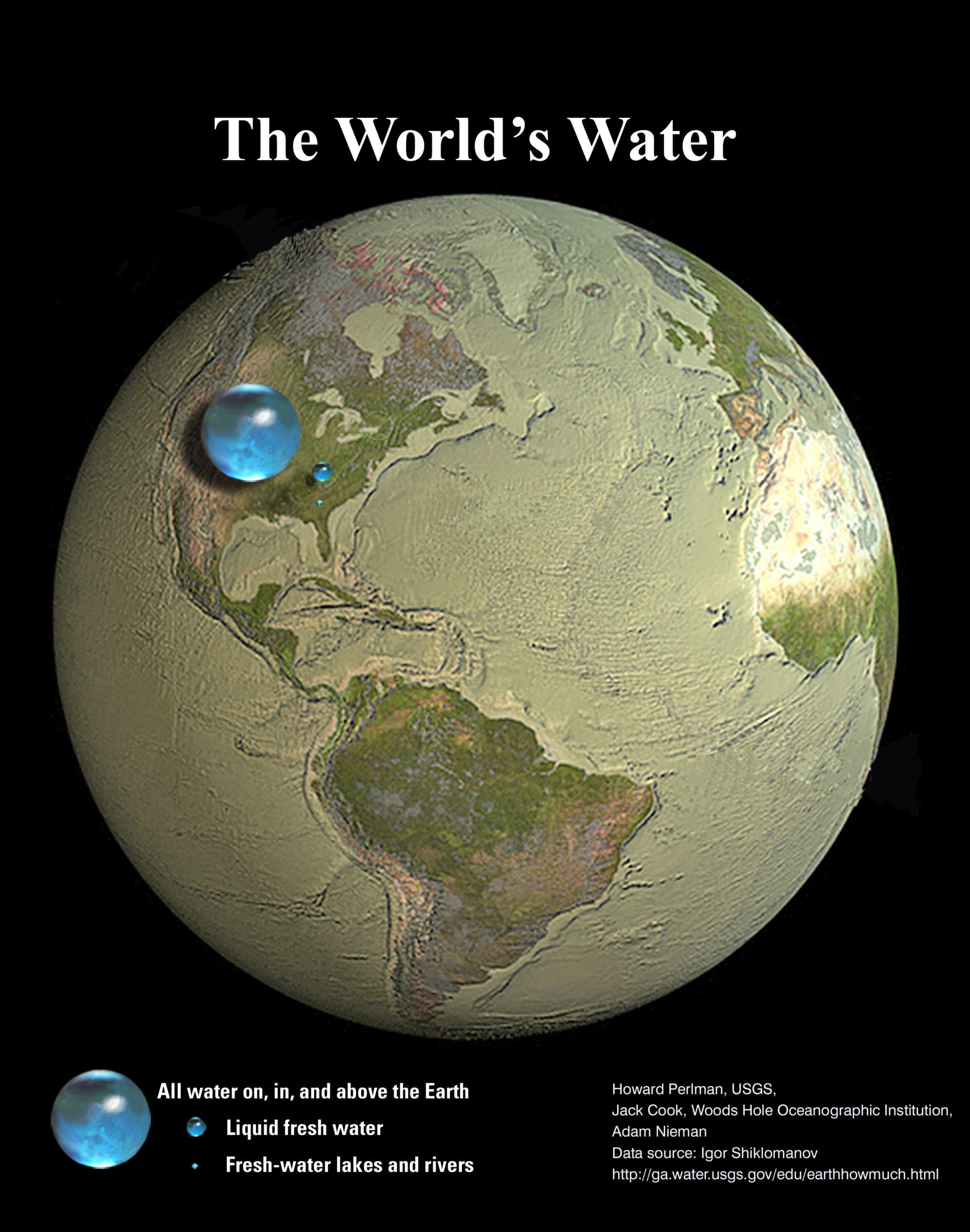

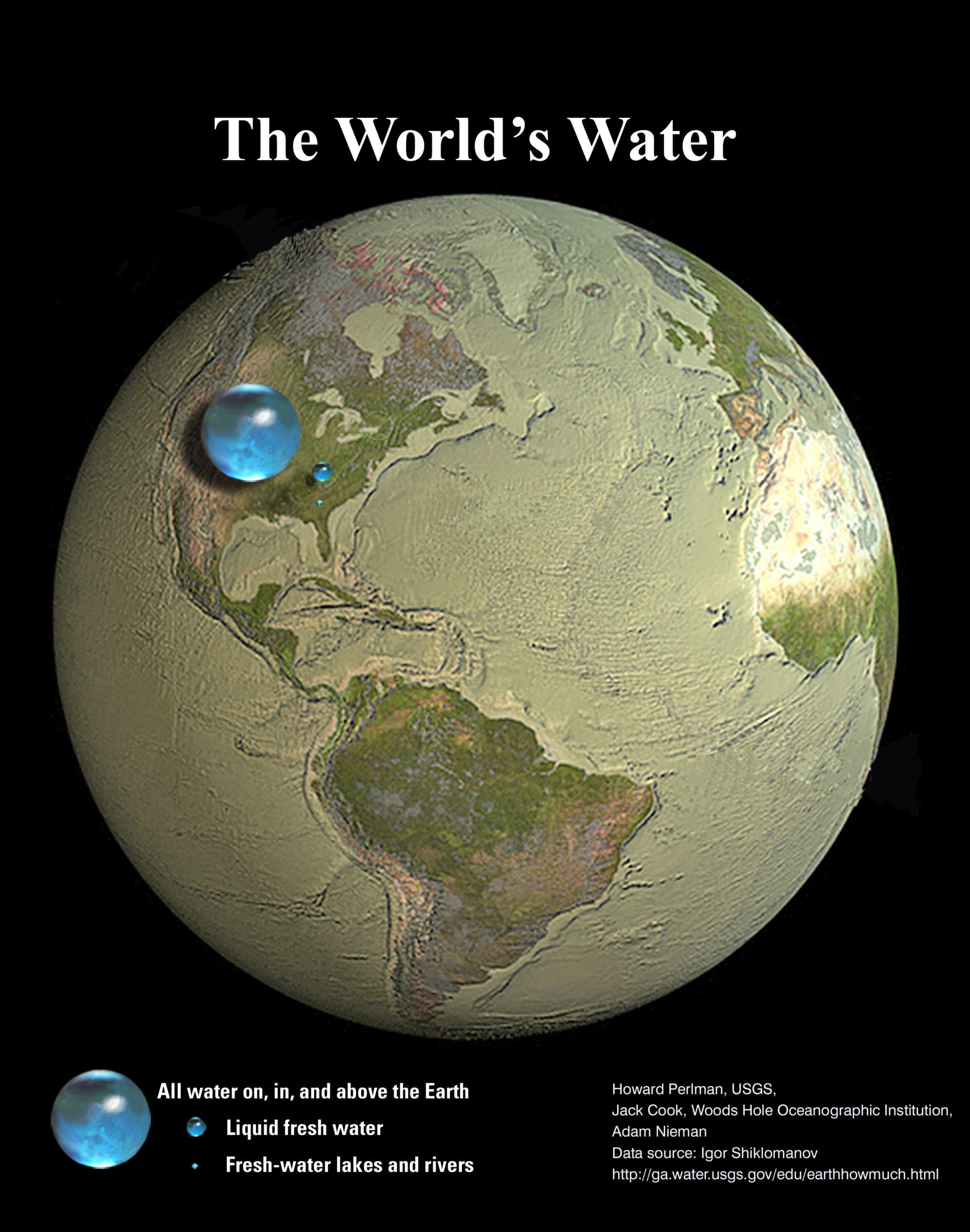

On top of that, fresh water is surprisingly scarce. A globe shows blue water covering our world. But that picture is misleading: 97.5 percent of the Earth’s water is salt water — corrosive, even toxic. The remaining 2.5 percent is fresh, but the great bulk of that is unreachable, either because it is locked into the polar ice caps, or because it is diffused in porous rock deep beneath the surface. If we could somehow collect the total world supply of rivers, lakes, and other fresh surface water in a single place — all the water that is easily available for the eight billion men, women, and children on Earth — it would form a sphere just 35 miles in diameter. Adding in reachable groundwater would add some miles to that sphere, but not enough to dramatically alter the fact that our water-covered globe just doesn’t have that much fresh water we can readily get our hands on.

Couldn’t we make more? It is true that salt water can be converted into fresh water. Desalination, as the technique is called, most commonly involves forcing water through extremely fine membranes that block salt molecules but let water molecules, which are smaller, pass through. The Western hemisphere’s biggest desalination plant, in Carlsbad, California, is a technological marvel, pumping out about 50 million gallons of fresh water every day, about 10 percent of the water supply for nearby San Diego. But it also cost about $1 billion to build, uses as much energy as a small town, and dumps 50 million gallons per day of leftover brine, which has attracted numerous lawsuits. For now, in most places, supplying fresh water will have to be done the way it has always been done: digging a well or finding a river, lake, or spring, then pumping or channeling the water where needed.

The Problem

No matter what its source, almost every way that humans use water makes it unfit for later use. Whether passed through an apartment dishwasher or a factory cooling system, a city toilet or a rural irrigation system, the result is an undrinkable, sometimes hazardous fluid that must be cleaned and recycled. When water engineers say, “We need clean water,” clean is the part they worry about.

Clean water is a necessity for more than just drinking. Almost three-quarters of human water use today is for agriculture, especially irrigation (out of all the world’s food, about 40 percent is grown on irrigated land). Another fifth of water use is by industry, where water is both a vital raw ingredient and a cleaning and cooling agent. Households are responsible for just one-tenth of global water consumption, but most of that is used for cleaning: washing dishes, washing clothes, washing people, washing away excrement.

Providing the clean water needed for all these purposes entails four basic functions:

Difficult as these technical issues are, they have been largely understood since biblical times and before. By far the biggest and most frustrating obstacle is instead what social scientists call “governmentality” — and what everybody else calls corruption, inefficiency, incompetence, and indifference.

The evidence is global and overwhelming. English cities lose a fifth of their water supply to leaks; Pennsylvania’s cities lose almost a quarter; cities in Brazil lose more than a third. So much of India’s urban water is contaminated that the cost of dealing with the resultant diarrhea is fully 2 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product. Texas loses so much water that just fixing the leaks could provide enough water for all of its major cities’ needs in the near future. All fifty states and all U.S. territories are plagued by water systems with lead pipes, which can leak dangerous lead into their water. The Mountain Aquifer between Israel and Palestine is the primary source of groundwater for both. In an atypical act of collaboration, both are overusing and polluting it. And so on.

by Charles C. Mann, The New Atlantis | Read more:

Image: Julie Wallace; USGS; Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant in Los Angeles, Aerial Archives/Alarmy

[ed. Third installment in the series How the System Works (New Atlantis).]

For as long as our species has lived in settled communities, we have struggled to provide ourselves with water. If modern agriculture, the subject of the previous article in this series, is a story of innovation and progress, the water supply has all too often been the opposite: a tale of stagnation and apathy. Even today, about two billion people, most of them in poor, rural areas, do not have a reliable supply of clean water — potable water, in the jargon of water engineers. Bad water leads to the death every year of about a million people. In terms of its immediate impact on human lives, water is the world’s biggest environmental problem and its worst public health problem — as it has been for centuries.

On top of that, fresh water is surprisingly scarce. A globe shows blue water covering our world. But that picture is misleading: 97.5 percent of the Earth’s water is salt water — corrosive, even toxic. The remaining 2.5 percent is fresh, but the great bulk of that is unreachable, either because it is locked into the polar ice caps, or because it is diffused in porous rock deep beneath the surface. If we could somehow collect the total world supply of rivers, lakes, and other fresh surface water in a single place — all the water that is easily available for the eight billion men, women, and children on Earth — it would form a sphere just 35 miles in diameter. Adding in reachable groundwater would add some miles to that sphere, but not enough to dramatically alter the fact that our water-covered globe just doesn’t have that much fresh water we can readily get our hands on.

Couldn’t we make more? It is true that salt water can be converted into fresh water. Desalination, as the technique is called, most commonly involves forcing water through extremely fine membranes that block salt molecules but let water molecules, which are smaller, pass through. The Western hemisphere’s biggest desalination plant, in Carlsbad, California, is a technological marvel, pumping out about 50 million gallons of fresh water every day, about 10 percent of the water supply for nearby San Diego. But it also cost about $1 billion to build, uses as much energy as a small town, and dumps 50 million gallons per day of leftover brine, which has attracted numerous lawsuits. For now, in most places, supplying fresh water will have to be done the way it has always been done: digging a well or finding a river, lake, or spring, then pumping or channeling the water where needed.

The Problem

No matter what its source, almost every way that humans use water makes it unfit for later use. Whether passed through an apartment dishwasher or a factory cooling system, a city toilet or a rural irrigation system, the result is an undrinkable, sometimes hazardous fluid that must be cleaned and recycled. When water engineers say, “We need clean water,” clean is the part they worry about.

Clean water is a necessity for more than just drinking. Almost three-quarters of human water use today is for agriculture, especially irrigation (out of all the world’s food, about 40 percent is grown on irrigated land). Another fifth of water use is by industry, where water is both a vital raw ingredient and a cleaning and cooling agent. Households are responsible for just one-tenth of global water consumption, but most of that is used for cleaning: washing dishes, washing clothes, washing people, washing away excrement.

Providing the clean water needed for all these purposes entails four basic functions:

- Finding, obtaining, and purifying the water that goes into the system;

- Delivering it to households and businesses;

- Cleaning up the water that leaves those homes and businesses; and

- Maintaining the network of pipes, pumps, and other structures responsible for the previous three functions.

Difficult as these technical issues are, they have been largely understood since biblical times and before. By far the biggest and most frustrating obstacle is instead what social scientists call “governmentality” — and what everybody else calls corruption, inefficiency, incompetence, and indifference.

The evidence is global and overwhelming. English cities lose a fifth of their water supply to leaks; Pennsylvania’s cities lose almost a quarter; cities in Brazil lose more than a third. So much of India’s urban water is contaminated that the cost of dealing with the resultant diarrhea is fully 2 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product. Texas loses so much water that just fixing the leaks could provide enough water for all of its major cities’ needs in the near future. All fifty states and all U.S. territories are plagued by water systems with lead pipes, which can leak dangerous lead into their water. The Mountain Aquifer between Israel and Palestine is the primary source of groundwater for both. In an atypical act of collaboration, both are overusing and polluting it. And so on.

by Charles C. Mann, The New Atlantis | Read more:

Image: Julie Wallace; USGS; Hyperion Water Reclamation Plant in Los Angeles, Aerial Archives/Alarmy

[ed. Third installment in the series How the System Works (New Atlantis).]