Monday, November 26, 2012

Positive Thinking is for Suckers!

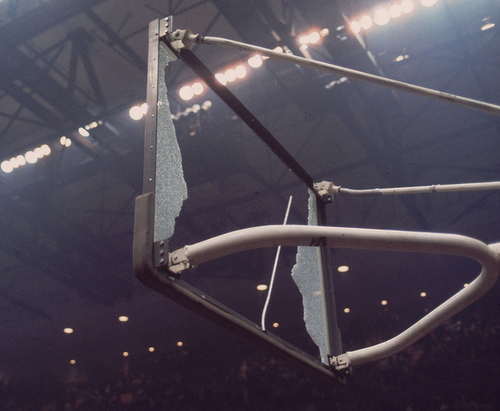

The man who claims that he is about to tell me the secret of human happiness is eighty-three years old, with an alarming orange tan that does nothing to enhance his credibility. It is just after eight o’clock on a December morning, in a darkened basketball stadium on the outskirts of San Antonio, and — according to the orange man — I am about to learn ‘the one thing that will change your life forever.” I’m skeptical, but not as much as I might normally be, because I am only one of more than fifteen thousand people at Get Motivated!, America’s “most popular business motivational seminar,” and the enthusiasm of my fellow audience members is starting to become infectious.

“So you wanna know?” asks the octogenarian, who is Dr. Robert H. Schuller, veteran self-help guru, author of more than thirty-five books on the power of positive thinking, and, in his other job, the founding pastor of the largest church in the United States constructed entirely out of glass. The crowd roars its assent. Easily embarrassed British people like me do not, generally speaking, roar our assent at motivational seminars in Texas basketball stadiums, but the atmosphere partially overpowers my reticence. I roar quietly.

“Here it is, then,” Dr. Schuller declares, stiffly pacing the stage, which is decorated with two enormous banners reading “MOTIVATE!” and “SUCCEED!,” seventeen American flags, and a large number of potted plants. “Here’s the thing that will change your life forever.” Then he barks a single syllable — “Cut!” — and leaves a dramatic pause before completing his sentence: ‘… the word ‘impossible’ out of your life! Cut it out! Cut it out forever!”

The audience combusts. I can’t help feeling underwhelmed, but then I probably shouldn’t have expected anything different from Get Motivated!, an event at which the sheer power of positivity counts for everything. “You are the master of your destiny!” Schuller goes on. “Think big, and dream bigger! Resurrect your abandoned hope! … Positive thinking works in every area of life!’

The logic of Schuller’s philosophy, which is the doctrine of positive thinking at its most distilled, isn’t exactly complex: decide to think happy and successful thoughts — banish the spectres of sadness and failure — and happiness and success will follow. It could be argued that not every speaker listed in the glossy brochure for today’s seminar provides uncontroversial evidence in support of this outlook: the keynote speech is to be delivered, in a few hours’ time, by George W . Bush, a president far from universally viewed as successful. But if you voiced this objection to Dr. Schuller, he would probably dismiss it as “negativity thinking.” To criticize the power of positivity is to demonstrate that you haven’t really grasped it at all. If you had, you would stop grumbling about such things, and indeed about anything else.

The organisers of Get Motivated! describe it as a motivational seminar, but that phrase — with its suggestion of minor-league life coaches giving speeches in dingy hotel ballrooms — hardly captures the scale and grandiosity of the thing. Staged roughly once a month, in cities across North America, it sits at the summit of the global industry of positive thinking, and boasts an impressive roster of celebrity speakers: Mikhail Gorbachev and Rudy Giuliani are among the regulars, as are General Colin Powell and, somewhat incongruously, William Shatner. Should it ever occur to you that a formerly prominent figure in world politics (or William Shatner) has been keeping an inexplicably low profile in recent months, there’s a good chance you’ll find him or her at Get Motivated!, preaching the gospel of optimism.

As befits such celebrity, there’s nothing dingy about the staging, either, which features banks of swooping spotlights, sound systems pumping out rock anthems, and expensive pyrotechnics; each speaker is welcomed to the stage amid showers of sparks and puffs of smoke. These special effects help propel the audience to ever higher altitudes of excitement, though it also doesn’t hurt that for many of them, a trip to Get Motivated! means an extra day off work: many employers classify it as job training. Even the United States military, where “training” usually means something more rigorous, endorses this view; in San Antonio, scores of the stadium’s seats are occupied by uniformed soldiers from the local Army base.

Technically, I am here undercover. Tamara Lowe, the self-described “world’s No. 1 female motivational speaker,” who along with her husband runs the company behind Get Motivated!, has been accused of denying access to reporters, a tribe notoriously prone to negativity thinking. Lowe denies the charge, but out of caution, I’ve been describing myself as a “self-employed businessman” — a tactic, I’m realizing too late, that only makes me sound shifty. I needn’t have bothered with subterfuge anyway, it turns out, since I’m much too far away from the stage for the security staff to be able to see me scribbling in my notebook. My seat is described on my ticket as “premier seating,” but this turns out to be another case of positivity run amok: at Get Motivated!, there is only “premier seating,” “executive seating,” and “VIP seating.”

In reality, mine is up in the nosebleed section; it is a hard plastic perch, painful on the buttocks. But I am grateful for it, because it means that by chance I’m seated next to a man who, as far as I can make out, is one of the few cynics in the arena — an amiable, large-limbed park ranger named Jim, who sporadically leaps to his feet to shout I’m so motivated!” in tones laden with sarcasm.

He explains that he was required to attend by his employer, the United States National Park Service, though when I ask why that organization might wish its rangers to use paid work time in this fashion, he cheerily concedes that he has “no fucking clue.” Dr. Schuller’s sermon, meanwhile, is gathering pace. “When I was a child, it was impossible for a man ever to walk on the moon, impossible to cut out a human heart and put it in another man’s chest … the word ‘impossible’ has proven to be a very stupid word!” He does not spend much time marshaling further evidence for his assertion that failure is optional: it’s clear that Schuller, the author of “Move Ahead with Possibility Thinking” and “Tough Times Never Last, but Tough People Do!,” vastly prefers inspiration to argument. But in any case, he is really only a warm-up man for the day’s main speakers, and within fifteen minutes he is striding away, to adulation and fireworks, fists clenched victoriously up at the audience, the picture of positive-thinking success.

It is only months later, back at my home in New York, reading the headlines over morning coffee, that I learn the news that the largest church in the United States constructed entirely from glass has filed for bankruptcy, a word Dr. Schuller had apparently neglected to eliminate from his vocabulary.

For a civilization so fixated on achieving happiness, we seem remarkably incompetent at the task. One of the best-known general findings of the “science of happiness” has been the discovery that the countless advantages of modern life have done so little to lift our collective mood. The awkward truth seems to be that increased economic growth does not necessarily make for happier societies, just as increased personal income, above a certain basic level, doesn’t make for happier people. Nor does better education, at least according to some studies. Nor does an increased choice of consumer products. Nor do bigger and fancier homes, which instead seem mainly to provide the privilege of more space in which to feel gloomy.

Perhaps you don’t need telling that self-help books, the modern-day apotheosis of the quest for happiness, are among the things that fail to make us happy. But, for the record, research strongly suggests that they are rarely much help. This is why, among themselves, some self-help publishers refer to the “eighteen-month rule,” which states that the person most likely to purchase any given self-help book is someone who, within the previous eighteen months, purchased a self-help book — one that evidently didn’t solve all their problems. When you look at the self-help shelves with a coldly impartial eye, this isn’t especially surprising. That we yearn for neat, book-sized solutions to the problem of being human is understandable, but strip away the packaging, and you’ll find that the messages of such works are frequently banal. The “Seven Habits of Highly Effective People” essentially tells you to decide what matters most to you in life, and then do it; “How to Win Friends and Influence People” advises its readers to be pleasant rather than obnoxious, and to use people’s first names a lot. One of the most successful management manuals of the last few years, “Fish!,” which is intended to help foster happiness and productivity in the workplace, suggests handing out small toy fish to your hardest-working employees.

As we’ll see, when the messages get more specific than that, self-help gurus tend to make claims that simply aren’t supported by more reputable research. The evidence suggests, for example, that venting your anger doesn’t get rid of it, while visualising your goals doesn’t seem to make you more likely to achieve them. And whatever you make of the country-by-country surveys of national happiness that are now published with some regularity, it’s striking that the “happiest” countries are never those where self-help books sell the most, nor indeed where professional psychotherapists are most widely consulted. The existence of a thriving “happiness industry” clearly isn’t sufficient to engender national happiness, and it’s not unreasonable to suspect that it might make matters worse.

Yet the ineffectiveness of modern strategies for happiness is really just a small part of the problem. There are good reasons to believe that the whole notion of “seeking happiness” is flawed to begin with. For one thing, who says happiness is a valid goal in the first place? Religions have never placed much explicit emphasis on it, at least as far as this world is concerned; philosophers have certainly not been unanimous in endorsing it, either. And any evolutionary psychologist will tell you that evolution has little interest in your being happy, beyond trying to make sure that you’re not so listless or miserable that you lose the will to reproduce.

Even assuming happiness to be a worthy target, though, a worse pitfall awaits, which is that aiming for it seems to reduce your chances of ever attaining it. “Ask yourself whether you are happy,” observed the philosopher John Stuart Mill, “and you cease to be so.” At best, it would appear, happiness can only be glimpsed out of the corner of an eye, not stared at directly. (We tend to remember having been happy in the past much more frequently than we are conscious of being happy in the present.) Making matters worse still, what happiness actually is feels impossible to define in words; even supposing you could do so, you’d presumably end up with as many different definitions as there are people on the planet. All of which means it’s tempting to conclude that “How can we be happy?” is simply the wrong question — that we might as well resign ourselves to never finding the answer, and get on with something more productive instead.

But could there be a third possibility, besides the futile effort to pursue solutions that never seem to work, on the one hand, and just giving up, on the other? After several years reporting on the field of psychology as a journalist, I finally realized that there might be. I began to think that something united all those psychologists and philosophers — and even the occasional self-help guru — whose ideas seemed actually to hold water. The startling conclusion at which they had all arrived, in different ways, was this: that the effort to try to feel happy is often precisely the thing that makes us miserable. And that it is our constant efforts to eliminate the negative — insecurity, uncertainty, failure, or sadness — that is what causes us to feel so insecure, anxious, uncertain, or unhappy. They didn’t see this conclusion as depressing, though. Instead, they argued that it pointed to an alternative approach, a “negative path” to happiness, that entailed taking a radically different stance towards those things that most of us spend our lives trying hard to avoid. It involved learning to enjoy uncertainty, embracing insecurity, stopping trying to think positively, becoming familiar with failure, even learning to value death. In short, all these people seemed to agree that in order to be truly happy, we might actually need to be willing to experience more negative emotions — or, at the very least, to learn to stop running quite so hard from them. Which is a bewildering thought, and one that calls into question not just our methods for achieving happiness, but also our assumptions about what “happiness” really means.

by Oliver Burkeman, Salon | Read more:

Photo: Pete Souza

Toques From Underground

For the past two years, in a loft apartment in downtown Los Angeles, Craig Thornton has been conducting an experiment in the conventions of high-end American dining. Several nights a week, a group of sixteen strangers gather around his dining-room table to eat delicacies he has handpicked and prepared for them, from a meticulously considered menu over which they have no say. It is the toughest reservation in the city: when he announces a dinner, hundreds of people typically respond. The group is selected with an eye toward occupational balance—all lawyers, a party foul that was recently avoided thanks to Google, would have been too monochrome—and, when possible, democracy. Your dinner companion might be a former U.F.C. heavyweight champion; the chef Ludo Lefebvre; a Food Network obsessive for whom any meal is an opportunity to talk about a different meal; or a kid who saved his money and drove four hours from Fresno to be there. At the end, you place a “donation”—whatever you think the meal was worth—in a desiccated crocodile head that sits in the middle of the table. Most people pay around ninety dollars; after buying the ingredients and paying a small crew, Thornton usually breaks even. The experiment is called Wolvesmouth, the loft Wolvesden; Thornton is the Wolf. “I grew up in a survival atmosphere,” he says. “I like that aggressiveness. And I like that it’s a shy animal that avoids confrontation.”

Thornton is thirty and skinny, five feet nine, with a lean, carved face and the playful, semi-wild bearing of a stray animal that half-remembers life at the hearth. People of an older generation adopt him. Three women consider themselves to be his mother; two men—neither one his father—call him son. Lost boys flock to him; at any given time, there are a couple of them camping on his floor, in tents and on bedrolls.

Thornton doesn’t drink, smoke, or often sleep, and he once lost fifteen pounds driving across the country because he couldn’t bring himself to eat road food. (At the end of the trip, he weighed a hundred and eighteen.) It is hard for him to eat while working—which sometimes means fasting for days—and in any case he always leaves food on the plate. “I like the idea of discipline and restraint,” he says. “You have to have that edge.” He dresses in moody blacks and grays, with the occasional Iron Maiden T-shirt, and likes his jeans girl-tight. His hair hangs to his waist, but he keeps it tucked up in a newsboy cap with cutouts over the ears. I once saw him take it down and shake it for a second, to the delight of a couple of female diners, then, sheepish, return it to hiding. One of his great fears is to be known as the Axl Rose of cooking.

For a confluence of reasons—global recession, social media, foodie-ism—restaurants have been dislodged from their traditional fixed spots and are loose on the land. Established chefs, between gigs, squat in vacant commercial kitchens: pop-ups. Young, undercapitalized cooks with catchy ideas go in search of drunken undergraduates: gourmet food trucks. Around the world, cooks, both trained and not, are hosting sporadic, legally questionable supper clubs and dinner parties in unofficial spaces. There are enough of them—five hundred or so—that two former Air B-n-B employees founded a site, Gusta.com, to help chefs manage their secret events. The movement is marked by ambition, some of it out of proportion to talent. “You’ve got a lot of people trying to be Thomas Keller in their shitty walkup,” one veteran of the scene told me. If you’re serving the food next to the litter box, how else are you going to get people to pay up?

At Wolvesmouth, Thornton has accomplished something rare: above-ground legitimacy, with underground preëminence. In February, Zagat put Thornton on its first “30 Under 30” list for Los Angeles. “Top Chef” has repeatedly tried to get him on the show, and investors have approached him with plans for making Wolvesmouth into a household name. But he has been reluctant to leave the safety of the den, where he exerts complete control. “I don’t want a business partner who’s like, ‘You know, my mom used to make a great meat loaf—I think we should do something with that,’ ” he told me. “I don’t necessarily need seventeen restaurants serving the kind of food I do. When someone gets a seat at Wolvesmouth, they know I’m going to be behind the stove cooking.” His stubbornness is attractive, particularly to an audience defined by its pursuit of singular food experiences. “He is obsessed with obscurity, which is why I love him,” James Skotchdopole, one of Quentin Tarantino’s producers and a frequent guest, says. Still, there is the problem of the neighbors, who let Thornton hold Wolvesmouth dinners only on weekends, when they are out of town. (He hosts smaller, private events, which pay the rent, throughout the week.) And there are the authorities, who have occasionally shut such operations down.

Getting busted is not always a calamity for the underground restaurateur, however. In 2009, Nguyen Tran and his wife, Thi, who had lost her job in advertising, started serving tofu balls and Vietnamese-style tacos out of their home, and within a few months their apartment was ranked the No. 1 Asian fusion restaurant in Los Angeles on Yelp. (Providence, a fantastically expensive restaurant with two Michelin Stars, was No. 2.) When the health department confronted Nguyen with his Twitter feed touting specials and warned him to stop, Thi was unnerved, but Nguyen insisted that the intervention was a blessing. They moved the restaurant, which they called Starry Kitchen, into a legitimate space, and burnished their creation myth. “It increased our audience,” he told me. “We were seedy, and being caught validated that we really were underground.”

Thornton is thirty and skinny, five feet nine, with a lean, carved face and the playful, semi-wild bearing of a stray animal that half-remembers life at the hearth. People of an older generation adopt him. Three women consider themselves to be his mother; two men—neither one his father—call him son. Lost boys flock to him; at any given time, there are a couple of them camping on his floor, in tents and on bedrolls.

Thornton doesn’t drink, smoke, or often sleep, and he once lost fifteen pounds driving across the country because he couldn’t bring himself to eat road food. (At the end of the trip, he weighed a hundred and eighteen.) It is hard for him to eat while working—which sometimes means fasting for days—and in any case he always leaves food on the plate. “I like the idea of discipline and restraint,” he says. “You have to have that edge.” He dresses in moody blacks and grays, with the occasional Iron Maiden T-shirt, and likes his jeans girl-tight. His hair hangs to his waist, but he keeps it tucked up in a newsboy cap with cutouts over the ears. I once saw him take it down and shake it for a second, to the delight of a couple of female diners, then, sheepish, return it to hiding. One of his great fears is to be known as the Axl Rose of cooking.

For a confluence of reasons—global recession, social media, foodie-ism—restaurants have been dislodged from their traditional fixed spots and are loose on the land. Established chefs, between gigs, squat in vacant commercial kitchens: pop-ups. Young, undercapitalized cooks with catchy ideas go in search of drunken undergraduates: gourmet food trucks. Around the world, cooks, both trained and not, are hosting sporadic, legally questionable supper clubs and dinner parties in unofficial spaces. There are enough of them—five hundred or so—that two former Air B-n-B employees founded a site, Gusta.com, to help chefs manage their secret events. The movement is marked by ambition, some of it out of proportion to talent. “You’ve got a lot of people trying to be Thomas Keller in their shitty walkup,” one veteran of the scene told me. If you’re serving the food next to the litter box, how else are you going to get people to pay up?

At Wolvesmouth, Thornton has accomplished something rare: above-ground legitimacy, with underground preëminence. In February, Zagat put Thornton on its first “30 Under 30” list for Los Angeles. “Top Chef” has repeatedly tried to get him on the show, and investors have approached him with plans for making Wolvesmouth into a household name. But he has been reluctant to leave the safety of the den, where he exerts complete control. “I don’t want a business partner who’s like, ‘You know, my mom used to make a great meat loaf—I think we should do something with that,’ ” he told me. “I don’t necessarily need seventeen restaurants serving the kind of food I do. When someone gets a seat at Wolvesmouth, they know I’m going to be behind the stove cooking.” His stubbornness is attractive, particularly to an audience defined by its pursuit of singular food experiences. “He is obsessed with obscurity, which is why I love him,” James Skotchdopole, one of Quentin Tarantino’s producers and a frequent guest, says. Still, there is the problem of the neighbors, who let Thornton hold Wolvesmouth dinners only on weekends, when they are out of town. (He hosts smaller, private events, which pay the rent, throughout the week.) And there are the authorities, who have occasionally shut such operations down.

Getting busted is not always a calamity for the underground restaurateur, however. In 2009, Nguyen Tran and his wife, Thi, who had lost her job in advertising, started serving tofu balls and Vietnamese-style tacos out of their home, and within a few months their apartment was ranked the No. 1 Asian fusion restaurant in Los Angeles on Yelp. (Providence, a fantastically expensive restaurant with two Michelin Stars, was No. 2.) When the health department confronted Nguyen with his Twitter feed touting specials and warned him to stop, Thi was unnerved, but Nguyen insisted that the intervention was a blessing. They moved the restaurant, which they called Starry Kitchen, into a legitimate space, and burnished their creation myth. “It increased our audience,” he told me. “We were seedy, and being caught validated that we really were underground.”

The Truce On Drugs

Three weeks ago, voters in Colorado and Washington chose to legalize marijuana for recreational use in both states—to make the drug legal to sell, legal to smoke, and legal to carry, so long as you are over 21 and you don’t drive while high. No doctor’s note is necessary. Marijuana will no longer be mostly regulated by the police, as if it were cocaine, but instead by the state liquor board (in Washington) and the Department of Revenue (in Colorado), as if it were whiskey. Colorado’s law has an extra provision that permits anyone to grow up to six marijuana plants at home and give away an ounce to friends.

It seems very unlikely that the momentum for legalization will stop on its own. About 50 percent of voters around the country now favor legalizing the drug for recreational use (the number only passed 30 percent in 2000 and 40 percent in 2009), and the younger you are, the more likely you are to favor legal pot. Legalization campaigns have the backing of a few committed billionaires, notably George Soros and Peter Lewis, and the polls suggest that the support for legalization won’t simply be confined to progressive coalitions: More than a third of conservatives are for full legalization, and there is a gender gap, with more men in favor than women. Perhaps most striking of all, an organized opposition seems to have vanished completely. In Washington State, the two registered groups opposing the referendum had combined by early fall to raise a grand total of $16,000. “We have a marriage-equality initiative on the ballot here, and it is all over television, the radio, the newspapers,” Christine Gregoire, the Democratic governor of Washington, told me just before the election. When it comes to marijuana, “it’s really interesting. You don’t hear it discussed at all.” A decade ago, legalization advocates were struggling to corral pledges of support for medicinal pot from very liberal politicians. Now, the old fearful talk about a gateway drug has disappeared entirely, and voters in two states have chosen a marijuana regime more liberal than Amsterdam’s.

These votes suggest what may be a spreading, geographic Humboldt of the mind, in which the liberties of pot in far-northern California, and the unusually ambiguous legal regime there, metastasize around the country. If you live in Seattle and sell licensed marijuana, your operation could be perfectly legal from the perspective of the state government and committing a federal crime at the same time. It is hard to detect much political enthusiasm for a federal pot crackdown, but the complexities that come with these new laws may be hard for Washington to simply ignore. What happens, for instance, when a New York dealer secures a license and a storefront in Denver, and then illegally ships the weed back home? Economists who have studied these questions thoroughly say that they can’t rule out a scenario in which little changes in the consumption of pot—the same people will smoke who always have. But they also can’t rule out a scenario in which consumption doubles, or more than doubles, and pot is not so much less prevalent than alcohol.

And yet the prohibition on marijuana is something more than just a fading relic of the culture wars. It has also been part of the ad hoc assemblage of laws, treaties, and policies that together we call the “war on drugs,” and it is in this context that the votes on Election Day may have their furthest reach. When activists in California tried to fully legalize marijuana there in 2010, the most deeply felt opposition came from the president of Mexico, who called the initiative “absurd,” telling reporters that an America that legalized marijuana had “very little moral authority to condemn a Mexican farmer who for hunger is planting marijuana to sustain the insatiable North American market for drugs.” This year, the reaction from the chief strategist for the incoming Mexican president was even broader and more pointed. The votes in Colorado and Washington, he said, “change somewhat the rules of the game … we have to carry out a review of our joint policies in regard to drug trafficking and security in general.” The suggestion from south of the border wasn’t that cocaine should be subject to the same regime as marijuana. It was: If we are going to rewrite the rules on drug policy to make them more sensible, why stop at only one drug? Why go partway?

Something unexpected has happened in the past five years. The condemnations of the war on drugs—of the mechanized imprisonment of much of our inner cities, of the brutal wars sustained in Latin America at our behest, of the sheer cost of prohibition, now likely past a trillion dollars—have migrated out from the left-wing cul-de-sacs that they have long inhabited and into the political Establishment. “The war on drugs, though well-intentioned, has been a failure,” New Jersey governor Chris Christie said this summer. A global blue-ribbon panel that included both the former Reagan secretary of State George Shultz and Kofi Annan had reached the same conclusion the previous June: “The global war on drugs has failed, with devastating consequences for individuals and societies.” The pressures from south of the border have grown far more urgent: The presidents of Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico, Honduras, Belize, and Costa Rica have all called for a broad reconsideration of the drug war in the past year, and the Organization of American States is now trying to work out what realistic alternatives there might be.

The war on drugs has always depended upon a morbid equilibrium, in which the cost of our efforts to keep narcotics from users is balanced against the consequences—in illness and death—of more widely spread use. But thanks in part to enforcement, addiction has receded in America, meaning, ironically, that the benefits of continuing prohibition have diminished. Meanwhile, the wars in Mexico and elsewhere have escalated the costs, killing nearly 60,000 people in six years. Together those developments have shifted the ethical equation. “There’s now no question,” says Mark Kleiman of UCLA, an influential drug-policy scholar, “that the costs of the drug war itself exceed the costs of drug use. It’s not even close.”

In many ways, what is happening right now is a collection of efforts, some liberating and some scary, to reset that moral calibration, to find a new equilibrium. The prohibition on drugs did not begin as neatly as the prohibition on alcohol once did, with a constitutional amendment, and it is unlikely to end neatly, with an act of a legislature or a new international treaty. Nor is the war on drugs likely to end with something that looks exactly like a victory. What is happening instead is more complicated and human: Without really acknowledging it, we are beginning to experiment with a negotiated surrender.

by Benjamin Wallace-Wells, New York Magazine | Read more:

Photo: Kenji Aoki

It seems very unlikely that the momentum for legalization will stop on its own. About 50 percent of voters around the country now favor legalizing the drug for recreational use (the number only passed 30 percent in 2000 and 40 percent in 2009), and the younger you are, the more likely you are to favor legal pot. Legalization campaigns have the backing of a few committed billionaires, notably George Soros and Peter Lewis, and the polls suggest that the support for legalization won’t simply be confined to progressive coalitions: More than a third of conservatives are for full legalization, and there is a gender gap, with more men in favor than women. Perhaps most striking of all, an organized opposition seems to have vanished completely. In Washington State, the two registered groups opposing the referendum had combined by early fall to raise a grand total of $16,000. “We have a marriage-equality initiative on the ballot here, and it is all over television, the radio, the newspapers,” Christine Gregoire, the Democratic governor of Washington, told me just before the election. When it comes to marijuana, “it’s really interesting. You don’t hear it discussed at all.” A decade ago, legalization advocates were struggling to corral pledges of support for medicinal pot from very liberal politicians. Now, the old fearful talk about a gateway drug has disappeared entirely, and voters in two states have chosen a marijuana regime more liberal than Amsterdam’s.

These votes suggest what may be a spreading, geographic Humboldt of the mind, in which the liberties of pot in far-northern California, and the unusually ambiguous legal regime there, metastasize around the country. If you live in Seattle and sell licensed marijuana, your operation could be perfectly legal from the perspective of the state government and committing a federal crime at the same time. It is hard to detect much political enthusiasm for a federal pot crackdown, but the complexities that come with these new laws may be hard for Washington to simply ignore. What happens, for instance, when a New York dealer secures a license and a storefront in Denver, and then illegally ships the weed back home? Economists who have studied these questions thoroughly say that they can’t rule out a scenario in which little changes in the consumption of pot—the same people will smoke who always have. But they also can’t rule out a scenario in which consumption doubles, or more than doubles, and pot is not so much less prevalent than alcohol.

And yet the prohibition on marijuana is something more than just a fading relic of the culture wars. It has also been part of the ad hoc assemblage of laws, treaties, and policies that together we call the “war on drugs,” and it is in this context that the votes on Election Day may have their furthest reach. When activists in California tried to fully legalize marijuana there in 2010, the most deeply felt opposition came from the president of Mexico, who called the initiative “absurd,” telling reporters that an America that legalized marijuana had “very little moral authority to condemn a Mexican farmer who for hunger is planting marijuana to sustain the insatiable North American market for drugs.” This year, the reaction from the chief strategist for the incoming Mexican president was even broader and more pointed. The votes in Colorado and Washington, he said, “change somewhat the rules of the game … we have to carry out a review of our joint policies in regard to drug trafficking and security in general.” The suggestion from south of the border wasn’t that cocaine should be subject to the same regime as marijuana. It was: If we are going to rewrite the rules on drug policy to make them more sensible, why stop at only one drug? Why go partway?

Something unexpected has happened in the past five years. The condemnations of the war on drugs—of the mechanized imprisonment of much of our inner cities, of the brutal wars sustained in Latin America at our behest, of the sheer cost of prohibition, now likely past a trillion dollars—have migrated out from the left-wing cul-de-sacs that they have long inhabited and into the political Establishment. “The war on drugs, though well-intentioned, has been a failure,” New Jersey governor Chris Christie said this summer. A global blue-ribbon panel that included both the former Reagan secretary of State George Shultz and Kofi Annan had reached the same conclusion the previous June: “The global war on drugs has failed, with devastating consequences for individuals and societies.” The pressures from south of the border have grown far more urgent: The presidents of Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico, Honduras, Belize, and Costa Rica have all called for a broad reconsideration of the drug war in the past year, and the Organization of American States is now trying to work out what realistic alternatives there might be.

The war on drugs has always depended upon a morbid equilibrium, in which the cost of our efforts to keep narcotics from users is balanced against the consequences—in illness and death—of more widely spread use. But thanks in part to enforcement, addiction has receded in America, meaning, ironically, that the benefits of continuing prohibition have diminished. Meanwhile, the wars in Mexico and elsewhere have escalated the costs, killing nearly 60,000 people in six years. Together those developments have shifted the ethical equation. “There’s now no question,” says Mark Kleiman of UCLA, an influential drug-policy scholar, “that the costs of the drug war itself exceed the costs of drug use. It’s not even close.”

In many ways, what is happening right now is a collection of efforts, some liberating and some scary, to reset that moral calibration, to find a new equilibrium. The prohibition on drugs did not begin as neatly as the prohibition on alcohol once did, with a constitutional amendment, and it is unlikely to end neatly, with an act of a legislature or a new international treaty. Nor is the war on drugs likely to end with something that looks exactly like a victory. What is happening instead is more complicated and human: Without really acknowledging it, we are beginning to experiment with a negotiated surrender.

by Benjamin Wallace-Wells, New York Magazine | Read more:

Photo: Kenji Aoki

Sunday, November 25, 2012

Rolling Stones

[ed. The entire documentary, (92 min.), including Altmont.]

5 Charts About Climate Change That Should Have You Very, Very Worried

Here are some of the more alarming graphic images from the reports.

1. Most of Greenland's top ice layer melted in four days

During a week in the summer of 2012, Greenland's ice cap went from melting on its periphery to melting over its entire surface (World Bank)

These shots published in the World Bank report show an unusually large ice melt over a four-day period, when an estimated 97% of Greenland's surface ice sheet had thawed by the middle of July 2012. Normally, ice sheets melt around the outer margins first where elevation is lower and allow for warmer temperatures. The event is uncommon, though not unprecedented. A similar event happened in 1889, and before that, several centuries earlier. There are indications, however, that the greatest amount of melting during the past 225 years has occurred in the last decade.

Photo: Unknown

On National Day of Listening, How to Get Someone's Story

In the middle of a conversation a friend once stopped me and said, "Tell me back everything I just told you." I couldn't. Not long after, he passed away, which made the lesson especially poignant. Most of us don't spend enough time really listening.

Now, as a therapist, I listen to stories professionally. Today, on the National Day of Listening, everyone is supposed to share stories. David Isay, founder of StoryCorps -- a Macarthur Genuis and an unwavering idealist -- also founded National Day of Listening because "every life matters equally, every voice matters equally, every story matters equally."

The project recalls Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration, to democratize oral history and create an archive of American voices. Since beginning in 2003, StoryCorps has recorded over 30,000 interviews from over 60,000 participants. In an interview David Isay said, "Listening to people reminds them that their lives matter."

The idea is simple: on the day after Thanksgiving family and friends often still gather together. The goal is to sit down for ten to twenty minutes with a loved one and really listen to their story.

The StoryCorps "Do-it-yourself guide" offers many wonderful questions for all types of interviews. And based on my personal mistakes as a young therapist, here are a few extra interview tips for today's National Day of Listening:

- Get comfortable, in a quiet place where you won't be interrupted. Cell phones off.

- Match body language. But do not do this so much that your interviewee says, "Did they teach you to imitate body language in therapy school?" Most communication happens non-verbally.

- Remind the person that you are there to listen and that they have an interesting story to tell. They do not have to "wow" you. They just need to be themselves and share what they know best (themselves).

- Start the questions off easy(ish), as in, "Tell me about your childhood."

- Do not start talking about yourself.

- Listen. Do not interrupt. Nod.

- Follow the emotion, go to what moves you.

- Later on, do not be afraid to ask hard questions. They do not have to answer.

- Some of the questions to ask a parent from the StoryCorps guide: "If you could do everything again, would you raise me differently?" "What was I like as a kid?" "What advice would you give me about raising my own kids?" "Are you proud of me?"

- Thank the person for sharing their story. Let them know their story is important. Tell them what moved you. Bring their story into the present. (...)

Video: StoryCorps/YouTube

On Growing Up White Trash

I am not white trash. I grew up white trash, though. When I was brought home from the hospital, I looked around the tiny lobby of our building and saw the dirty walls, the broken mailboxes, and the missing tiles on the floor. German shepherds wandered on the landings, and a beautiful girl wailed at a locked door to be taken back. I heard the radios blaring rock ballads from open apartment doors and the men standing in the doorways in their underwear, and I thought, great, I’ve been born into a poor family. But it didn’t seem so bad.

Growing up, all our furniture came from the garbage. We never threw anything out. How could you know what was garbage when our whole building looked like it was made from trash? The clock on the wall was a gangster that shot out machine gun noises on the hour. We had fake stained glass unicorns hanging from little suction cup hooks on the living-room window. We had stacks of old telephone books and a fish tank with no fish in it. It was typical white trash decor, shocking to no one. We weren’t exactly entertaining guests from other neighbourhoods.

By the time I was eleven, many of my friends were always being taken off to foster care when their moms had breakdowns or got arrested or had particularly shitty new boyfriends. Everybody had regular visits with social workers. In the summer, they gave us free passes to the amusement park. The Ferris wheel would turn around and around, filled with scared white trash children with their eyes closed—a little white trash solar system.

The white trash girls wore cut-off jean shorts and high heels over gym socks, and tied shoelaces around their wrists. The boys wore T-shirts with heavy metal bands, and jean jackets with silver-studded sleeves. All of the kids had bangs down to their noses. We never saw each other’s eyes. This was good for looking tough, and for hiding when you were crying. All of the kids had potty mouths. The only word not spoken out loud was “welfare.” A person could get stuck on it for years. You could be three generations on welfare.

When I turned thirteen and started noticing boys, I decided that my type was Judd Nelson as the teenage delinquent in The Breakfast Club. There weren’t any jocks or nerds around. I had a boyfriend named Shaun who wore a porkpie hat he had stolen off a snowman. He wrote the worst poetry on earth. He was in grade seven math for three years straight. He tried to sell photocopies of his drawings of ninjas on the street corner. Afterward, I dated Derek, who had a pet pigeon named Homer. He lived with his dad and slept on the couch. His dad kicked both of them out one day. Derek was sent to live in a foster home. I don’t know what happened to the pigeon.

When I was fifteen, I had a crush on a boy named Lionel who had a long scar on his arm where his dad had stabbed him when he was nine. He was known for having the high score on the Donkey Kong machine at the back of the corner store. He held up a gas station one night with his older brother. He came over with a suitcase full of stolen cigarettes and Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups.

I went on a date with a boy named Paul. His grandmother was raising him. She wore a winter coat all year long, even in the house. The peeling wallpaper of their apartment was covered in cherry trees. There were cockroaches in the teacups that you had to shake out into the sink.

We didn’t judge each other because we were poor. It would be like yelling at someone because it was raining. I just felt pretty and light headed when those boys were around. They thought I was a genius because I was the only kid from our circle who did really well at school.

When you’re a child, you become best friends with whoever lives across the street. But when I started high school, I was placed in all the advanced classes, and I joined extracurricular activities like the chess club. I started to make friends from different backgrounds. We had more in common, like books and alternative movies, and they opened up different worlds to me.

When I was fifteen, I was walking down the street with a boy I had recently made friends with and sort of liked. He was middle class and very nerdy. I had always wanted to be friends with a nerd. According to all the movies, they liked and accepted everyone. Out of nowhere, he said, “My mother says you’re not going to do anything with your life.”

“What, is the woman a fortune teller? How could she possibly know something like that?”

“She says you’re white trash, like the rest of your family.”

The boy said it as if it shouldn’t even bother me. He said it in the way that you tell a dog it can’t sit at the table because it is a dog. He said it as if everyone knew my place in the world, so I must know it, too. I just stood there on the sidewalk, not making eye contact. I suddenly realized that my new friends had been looking down on me.

By Heather O'Neill, The Walrus | Read more:

Photo: Untitled (Door on William), 1979, from the Vancouver Nights series.

Atomic Bread Baking at Home

When Hana enters the small bakery I have borrowed for a day, I am dividing a loaf into 1.5-centimeter slices. The loaf's tranches articulate a white fanned deck, each one the exact counterpart of its fellows. The bread is smooth and uniform, like a Bauhaus office block. There are no unneeded flourishes or swags. Each symmetrical slice shines so white it is almost blue. This is a work of modern art. My ten-year-old daughter does not pause to say hello. She rushes to the cutting board, aghast, and blurts, "Its fake!" Then she devours a piece in three bites, and asks for more.

When Hana enters the small bakery I have borrowed for a day, I am dividing a loaf into 1.5-centimeter slices. The loaf's tranches articulate a white fanned deck, each one the exact counterpart of its fellows. The bread is smooth and uniform, like a Bauhaus office block. There are no unneeded flourishes or swags. Each symmetrical slice shines so white it is almost blue. This is a work of modern art. My ten-year-old daughter does not pause to say hello. She rushes to the cutting board, aghast, and blurts, "Its fake!" Then she devours a piece in three bites, and asks for more.I have just spent a day re-creating the iconic loaf of 1950s-era soft white industrial bread, using easily acquired ingredients and home kitchen equipment. With the help of a 1956 government report detailing a massive, multiyear attempt to formulate the perfect loaf of white bread, achieving that re-creation proved relatively easy. Until Hana's arrival, however, I did not fully understand why I was doing it. I had sensed that extracting this industrial miracle food of yesteryear from the dustbin of kitsch might have something to teach about present-day efforts to change the food system; that it might offer perspective on our own confident belief that artisanal eating can restore health, rebuild community, and generally save the world. But, really, it was reactions like Hana's that I wanted to understand. How can a food be so fake and yet so eagerly eaten, so abhorred and so loved?

Sliced white bread as we know it today is the product of early twentieth-century streamlined design. It is the Zephyr train of food. But, in the American imagination, industrial loaves are more typically associated with the late '50s and early '60s—the Beaver Cleaver days of Baby Boomer nostalgia, the Golden Age of Wonder Bread. This is not without justification: during the late '50s and early '60s, Americans ate a lot of it. Across race, class, and generational divides, Americans consumed an average of a pound and a half of white bread per person, every week. Indeed, until the late '60s, Americans got from 25 to 30 percent of their daily calories from the stuff, more than from any other single item in their diet (and far more than any single item contributes to the American diet today—even high-fructose corn syrup).

Only a few years earlier, however, as world war morphed into cold war, the future of industrial bread looked uncertain. On the cusp of the Wonder years, Americans still ate enormous quantities of bread, but, even so, government officials and baking-industry experts worried that bread would lose its central place on the American table. In a world of rising prosperity and exciting new processed foods, the Zephyr train of food looked a bit tarnished. And so, in 1952, hoping to offset possible declines in bread consumption, the U.S. Department of Agriculture teamed up with baking-industry scientists to launch the Manhattan Project of bread.

Conceived as an intensive panoramic investigation of the country's bread-eating habits, the project had ambitious goals: First, gain a precise, scientific understanding of exactly how much and what kind of bread Americans ate, when and why they ate it, and what they thought about it. Second, use that information to engineer the perfect loaf of white bread—a model for all industrial white bread to come.

After two years of preliminary research, focus groups, failed loaves, and exploratory taste tests around the country, the project reached its culmination in Rockford, Illinois. In the early '50s, all the whiz kids of market research flocked to Rockford. An industrial center built by European immigrants, daring inventors, and strong labor unions, the city was the stuff of middle-class dreams. Although its economy was far more industrial than the national average, it suited America's self-image to think of it as the country's most "typical" city, and sociologists obliged with the label. In 1949, Life magazine declared that Rockford was "as nearly typical of the U.S. as any city can be." This was a place where prototypical Americans could be viewed in their natural habitat.

Thus, in 1954, USDA investigators journeyed from Chicago and Washington, D.C., to the shores of the Rock River to select two test groups, each comprising three hundred families "scientifically representative" of a typical American community. Over the next two years, the market researchers would deploy all the techniques of their emerging field on these six hundred families. They tracked bread purchases, devised means of weighing every ounce of bread consumed by the test population, conducted long interviews with housewives, and distributed thousands of questionnaires. Most important, they created a double-blind experiment that asked every member of every family to assess five different white-bread formulas over six weeks. Four years and almost one hundred thousand slices of bread after the project's conception, a clear portrait of America's favorite loaf emerged. It was 42.9 percent fluffier than the existing industry standard and 250 percent sweeter.

This is the bread I sought to reproduce—"USDA White Pan Loaf No. 1"—the archetype of 1950s-vintage American bread. I'm far from the American heartland, however. I'm living in the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico. When the industrial-bread-baking bug bit me in this hot and unfamiliar place, I despaired at first. But Mexico is not as inappropriate a place to bake Cold War-era American white bread as you might think. In the early twenty-first century, U.S. companies no longer lead the world in the production of "American" bread. Today, the world's most dynamic producer of sliced white bread is a Mexican multinational—Grupo Bimbo. Headquartered in the elite Mexico City business district of Santa Fe, Bimbo has almost ten billion dollars in global sales, one hundred thousand employees, and operations in eighteen countries, from Chile to China. Since 1996, it has also quietly acquired many of the United States' most iconic bakery brands. After its takeovers of Weston Foods in 2009 and Sara Lee in 2011, the Mexican company poised itself to become the United States' largest industrial bread baker.

How white bread took root in the land of the corn tortilla is a long story, but, like the story of USDA White Pan Loaf No. 1, it is a story of the early Cold War. After World War II, U.S. officials, Rockefeller Foundation scientists, and the Mexican government collaborated to undermine the allure of communism with cheap, plentiful, industrially produced wheat. Infusions of high-tech U.S. baking equipment and know-how then allowed Mexican companies like Bimbo to turn that wheat into cheap, abundant bread. Who knows whether U.S. food policy actually helped prevent the spread of communism south of the Rio Grande, but it did create a country with a taste for white bread—and a company with the ability to lead the world in its production.

So while there may be no better place in the world to bake American industrial bread than Mexico, living here means that I'm far from my own oven, mixer, scale, and familiar ingredients. I turn for help to Monique Duval, owner of a tiny artisanal bakery in Merida, and one of the founding members of Slow Food Yucatan. She says she appreciates my irony and agrees to let me use her space. On the way, I pick up a loaf of Bimbo for good luck.

Surprisingly, the formula for "USDA No. 1," as I begin to call it, is relatively simple. The ingredients are straightforward and easily found: enriched white-bread flour, water, nonfat milk solids, sugar, lard, salt, and yeast. And, although the instructions are written for a fully automated bakery, I'm able to adapt them for home use (a complete recipe appears at the end of this article). Only one piece of the formula gives me trouble—something cryptically referred to as "yeast food." The name is misleading. "Yeast foods" are, in fact, a class of mineral salts and enzymes that don't so much "feed" Saccharomyces microbes as help them eat faster, longer, and more effectively by breaking starches into the simpler sugars yeast consumes, by creating a more amenable dining environment, or by promoting the formation of strong gluten strands to trap the carbon-dioxide gas produced after it eats.

Since I have no idea what the USDA bakers used for yeast food in the early '50s, or how to acquire it in Mexico, I resign myself to using humanity's oldest yeast food—sugar—as a substitute. Then, walking home from the gym the day before I am to begin my experiment, I stumble upon a mom-and-pop bakery-supply store. There, amid unlabeled bags of grains and white powders, I discover mejorante para pan blanco. Let's call it "the Magic Powder."

by Aaron Bobrow-Strain, The Believer | Read more:

Photo by Russell Lee. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress and the U.S. Farm Security AdministrationSaturday, November 24, 2012

Why Black Friday Is a Behavioral Economist’s Nightmare

There are many, many reasons not to participate in Black Friday. Maybe you like sleeping in and spending time with family more than lining up in a mall parking lot at 2 a.m. Maybe you object on humanitarian grounds to the ever-earlier opening times, which force employees of big-box retailers to cut their holidays short by reporting to work in the middle of the night. (Or, increasingly, on Thanksgiving itself.)

But among the most potent reasons no sane person should participate in Black Friday is this: It is carefully designed to make you behave like an idiot.

The big problem with Black Friday, from a behavioral economist's perspective, is that every incentive a consumer could possibly have to participate — the promise of "doorbuster" deals on big-ticket items like TVs and computers, the opportunity to get all your holiday shopping done at once — is either largely illusory or outweighed by a disincentive on the other side. It's a nationwide experiment in consumer irrationality, dressed up as a cheerful holiday add-on.

As Dan Ariely explains in his book, Predictably Irrational, "We all make the same types of mistakes over and over, because of the basic wiring of our brains."

This applies to shopping on the other 364 days of the year, too. But on Black Friday, our rational decision-making faculties are at their weakest, just as stores are trying their hardest to maximize your mistakes. Here are just a few of the behavioral traps you might fall into this Friday:

The doorbuster: The doorbuster is a big-ticket item (typically, a TV or other consumer electronics item) that retailers advertise at an extremely low cost. (At Best Buy this year, it's this $179.99 Toshiba TV.) We call these things "loss-leaders," but rarely are the items actually sold at a loss. More often, they're sold at or slightly above cost in order to get you in the store, where you'll buy more stuff that is priced at normal, high-margin levels.

That's the retailer's Black Friday secret: You never just buy the TV. You buy the gold-plated HDMI cables, the fancy wall-mount kit (with the installation fee), the expensive power strip, and the Xbox game that catches your eye across the aisle. And by the time you're checking out, any gains you might have made on the TV itself have vanished. (...)

Irrational escalation: This behavioral quirk is also known as the "sunk cost fallacy," and it means that people are bad at knowing when to give up on unprofitable endeavors. This happens a lot on Black Friday. If you've already made the initial, bad investment of getting up at 2 a.m., driving to the mall, finding parking, and waiting in line for a store to open, you'll be inclined to buy more than you initially came for. (Since, after all, you're already there, and what's another few hundred dollars?)

Pain anesthetization: One of my favorite pieces of shopping-related research is a 2007 paper called "Neural Predictors of Purchases" [PDF] which used fMRI scans of shoppers' brains to show how deeply irrational the purchasing process is. Researchers found that if a shopper saw a price that was lower than expected, his medial prefrontal cortex (the part of the brain responsible for decision-making) lit up, while higher-than-expected prices caused the insula (the pain-registering part) to go wild. That brain activity had a strong correlation to whether or not the shoppers ended up buying the products or not.

Economists typically think of consumer choice as dispassionate cost-benefit analysis by rational market actors — a bunch of people saying to themselves, "Will having this $179.99 TV now create more pleasure than having the $179.99 in my bank account to do other things in the future?" — but the 2007 study shows that shoppers don't actually behave that way at all. In fact, they're choosing between immediate pleasure and immediate pain.

That explains why, on Black Friday, retailers pull out every trick in their playbook to minimize the immediate pain of buying: instant rebates, in-house credit cards with one-time sign-up discounts, multi-year layaway plans, and the like. The problem, of course, is that those methods of short-term anesthetization often carry long-term consequences — like astronomically high interest rates and hidden fees.

But among the most potent reasons no sane person should participate in Black Friday is this: It is carefully designed to make you behave like an idiot.

The big problem with Black Friday, from a behavioral economist's perspective, is that every incentive a consumer could possibly have to participate — the promise of "doorbuster" deals on big-ticket items like TVs and computers, the opportunity to get all your holiday shopping done at once — is either largely illusory or outweighed by a disincentive on the other side. It's a nationwide experiment in consumer irrationality, dressed up as a cheerful holiday add-on.

As Dan Ariely explains in his book, Predictably Irrational, "We all make the same types of mistakes over and over, because of the basic wiring of our brains."

This applies to shopping on the other 364 days of the year, too. But on Black Friday, our rational decision-making faculties are at their weakest, just as stores are trying their hardest to maximize your mistakes. Here are just a few of the behavioral traps you might fall into this Friday:

The doorbuster: The doorbuster is a big-ticket item (typically, a TV or other consumer electronics item) that retailers advertise at an extremely low cost. (At Best Buy this year, it's this $179.99 Toshiba TV.) We call these things "loss-leaders," but rarely are the items actually sold at a loss. More often, they're sold at or slightly above cost in order to get you in the store, where you'll buy more stuff that is priced at normal, high-margin levels.

That's the retailer's Black Friday secret: You never just buy the TV. You buy the gold-plated HDMI cables, the fancy wall-mount kit (with the installation fee), the expensive power strip, and the Xbox game that catches your eye across the aisle. And by the time you're checking out, any gains you might have made on the TV itself have vanished. (...)

Irrational escalation: This behavioral quirk is also known as the "sunk cost fallacy," and it means that people are bad at knowing when to give up on unprofitable endeavors. This happens a lot on Black Friday. If you've already made the initial, bad investment of getting up at 2 a.m., driving to the mall, finding parking, and waiting in line for a store to open, you'll be inclined to buy more than you initially came for. (Since, after all, you're already there, and what's another few hundred dollars?)

Pain anesthetization: One of my favorite pieces of shopping-related research is a 2007 paper called "Neural Predictors of Purchases" [PDF] which used fMRI scans of shoppers' brains to show how deeply irrational the purchasing process is. Researchers found that if a shopper saw a price that was lower than expected, his medial prefrontal cortex (the part of the brain responsible for decision-making) lit up, while higher-than-expected prices caused the insula (the pain-registering part) to go wild. That brain activity had a strong correlation to whether or not the shoppers ended up buying the products or not.

Economists typically think of consumer choice as dispassionate cost-benefit analysis by rational market actors — a bunch of people saying to themselves, "Will having this $179.99 TV now create more pleasure than having the $179.99 in my bank account to do other things in the future?" — but the 2007 study shows that shoppers don't actually behave that way at all. In fact, they're choosing between immediate pleasure and immediate pain.

That explains why, on Black Friday, retailers pull out every trick in their playbook to minimize the immediate pain of buying: instant rebates, in-house credit cards with one-time sign-up discounts, multi-year layaway plans, and the like. The problem, of course, is that those methods of short-term anesthetization often carry long-term consequences — like astronomically high interest rates and hidden fees.

by Kevin Roose, New York Magazine | Read more:

Photo: Unknown

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)