Friday, February 19, 2021

History of Zork

Zork

a.k.a DungeonIf Adventure had introduced hackers to an intriguing new genre of immersive text game, Zork was what brought it to the public at large. In the early 1980s, as the personal computer revolution reached into more and more homes, a Zork disk was a must-buy for first-time computer owners. By 1982 it had become the industry’s bestselling game. In 1983, it sold even more copies. Playboy covered it; so did Time, and American astronaut Sally Ride was reportedly obsessed with it. In 1984 it was still topping sales charts, beating out much newer games including its own sequels. At the end of 1985 it was still outselling any other game for the Apple II, half a decade after its first release on the platform, and had become the bestselling title of all time on many other systems besides.

by Tim Anderson, Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Dave Lebling

First Appeared: late June 1977

First Commercial Release: December 1980

Language: MDL

Platform: PDP-10

Opening Text: You are in an open field west of a big white house, with a boarded front door. There is a small mailbox here.

[Note: contains spoilery discussion of the jeweled egg, cyclops, and robot puzzles.]

Its creation can be traced to a heady Friday in May 1977 on the MIT campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was the last day of finals week, and summer was kicking off with a bang for the school’s cohort of tech-obsessed engineers: a new movie called Star Wars opened that day in theaters, the groundbreaking Apple II had just been released, and Adventure was exploding across the terminals of computer labs nationwide, thousands of students having no further distractions, at last, to keep them from solving it.

Among those obsessive players were four friends at a campus research lab, the Dynamic Modeling Group. Within two weeks they’d solved Adventure, squeezing every last point from it through meticulous play and, eventually, the surgical deployment of a machine-language debugger. Once the game was definitively solved, they immediately hatched plans to make something better. Not just to prove the superiority of their school’s coding prowess over Don Woods at Stanford—though that was undoubtedly part of it—nor simply because many were dragging their feet on graduating or finding jobs, and a challenging new distraction seemed immensely appealing—though that was part of it too. But the most important factor was that Adventure had been so incredibly fun and, regrettably, there wasn’t any more of it. “It was like reading a Sherlock Holmes story,” one player recalled, “and you wanted to read another one of them immediately. Only there wasn’t one, because nobody had written it.”

The four friends were an eclectic group of grad students ranging in age from 22 to 28, united by shared sensibilities and a love of hacking. Dave Lebling had a political science degree and had started programming only because of an accidental hole in his freshman year schedule. A “voracious reader” and “frustrated writer,” he’d helped design Maze in 1973, one of the earliest graphical exploration games and first-person shooters. Marc Blank was young, tall, thin, and technically enrolled in med school, but found messing around with computers an addictive distraction. Bruce Daniels was nearing thirty and increasingly bored with his PhD topic; he’d helped develop the lab’s pet project, the MDL programming language, and was always eager to find new ways of showing it off. And Tim Anderson was close to finishing his master’s but none too excited about leaving the heady intellectual community at MIT. With Adventure solved, the four sat down to hack together a prototype for an improved version, which would run like the earlier game on a PDP-10 mainframe. Needing a placeholder name for the source file, they typed in zork, one of many nonsense words floating around campus that could, among other usages, be substituted for an offensive interjection.

The game they began to create was at first quite similar to Adventure, so much so that historian Jimmy Maher has noted parts of it are more remake than homage. Both games begin in a forest outside a house containing supplies for an underground expedition, including food, water, and a light source with limited power; in both you search for treasures in a vast underground cave system and score points by returning them to the building on the surface; both feature underground volcanoes, locked grates, trolls, and a “maze of twisty little passages, all alike.” Hacker tropes and nods to other early text games abound, like a huge bat who whisks you off to another location like in Hunt the Wumpus. But as Zork expanded, it began to develop its own character: less realistic than the caverns sketched from Will Crowther’s real-life experience, but also more whimsical, more threatening, and driven by an improved parser and world model.

>open trap door

The door reluctantly opens to reveal a rickety staircase descending into darkness.

>down

It is pitch black. You are likely to be eaten by a grue. Your sword is glowing with a faint blue glow.

>what is a grue?

The grue is a sinister, lurking presence in the dark places of the earth. Its favorite diet is adventurers, but its insatiable appetite is tempered by its fear of light. No grue has ever been seen by the light of day, and few have survived its fearsome jaws to tell the tale.

The infamous grues were invented as a solution to a sort of bug: not with the game’s code, but with the player’s suspension of disbelief. In early versions of Zork, as in Adventure, you’d fall into a bottomless pit if you tried to move through a dark room without a portable light source. But someone noticed this could happen in Zork even in the dark attic of the above-ground house. Lebling, stealing the word “grue” from a Jack Vance novel, invented a new and more broadly applicable threat for dark places.

by Aaron A. Reed, Substack | Read more:

Image: via

[ed. A great classic. From the series 50 Years of Text Games.]

Racoon Trouble

Soon after he became a raccoon trapper, Musa Ramada began having nightmares, waking with the sensation that one of the animals was on his chest. Again and again this happened, upsetting him more and more; eventually he told his boss, an old tough guy named Steve. Steve knew these dreams well and offered advice for escaping them: when you trap a raccoon and its babies, release them together, he said. Ramada started doing so religiously, even when it cost him time and money. His sleep has been undisturbed by raccoons ever since.

No longer consigned to the urban edge, raccoons have infiltrated New York City, occupying homes and generating steady business for people who catch them. The past five years has seen a rise in raccoon trouble—subway lines shut down, brownstones vandalized—that has become even more noticeable during the pandemic, with New Yorkers holed up indoors. Raccoons have been spotted in the West Village, on the Upper East Side, in groups of more than twenty (the collective noun is a “gaze”) among the trees of Prospect Park. In 2016, the New York Times ran a feature headlined “Raccoons Invade Brooklyn,” with tales of backyard chickens being mauled and baby raccoons, known as kits, tumbling from apartment roofs. When a tourist inquired on Reddit about where one might encounter raccoons in the city, someone responded: “Come to Queens! They’re everywhere! Just had to throw one out of my bathtub.” (...)

A Syrian immigrant in his 40s, Ramada moved to New York in the 1990s to study computer science but dropped out when he couldn’t afford tuition. Since then, he’s passed through a series of marginal jobs, from construction and fixing cars to being a cook in an Italian restaurant. About four years ago he became a trapper entirely by accident, after responding to an online advertisement that he believed was related to house painting. At the interview, Steve, the boss, asked Ramada if he knew how to climb a ladder. “I said sure,” Ramada told me. “He said, high ladder—like 40 feet.” When Ramada found out he’d be catching raccoons, he was taken aback; that Americans would pay you to remove wild animals from their houses was something he’d never imagined. Back home, he said, this would be the duty of young men—a son or a cousin looking to demonstrate his bravery. But home was here now, in this city of money and exclusion that creates its own forms of opportunity. “Sure,” he told Steve, rolling the r, and just like that he was hired.

Ramada is in his forties, with grey stubble, scruffy hair, and tobacco-stained teeth. He rolls stubby joints of cheap pot purchased from a contact in the Bronx and cruises around, lightly stoned, with his traps and the junk that fills his panel van: tools for keeping the engine going; scraps of paper with the scribbled addresses of his customers (which he otherwise forgets); husks of sunflower seeds (he says he’s addicted); and books by Naguib Mahfouz, the Egyptian Nobel laureate who published 34 novels and more than 350 short stories, nearly all of which Ramada says he has read.

I first met him in November 2019, soon after he stopped working for Steve and started his own trapping company. I had been calling raccoon trappers for days, but most of them declined to speak to me; even Steve had fobbed me off, claiming that his bosses were “at their holiday house upstate.” (It was only later, when I met Ramada, that I began piecing the story together: Steve is one of the biggest trappers in New York, and emphatically has no boss.) Another trapper spoke to me on background for 45 minutes and made me promise not to refer to a word of our conversation. Others put the phone down when they heard the word “journalist.” But Ramada, when I reached him, acted as if he’d been waiting for me to call. His accent was very different from those of the gruff New Yorkers I’d been dealing with. First, with conviction, he told me he could communicate with raccoons. Then he asked me if I could help him design a website.

He’d spent hours trying to find customers, printing business cards and creating listings on Google Maps, but his rivals were far ahead of him, often operating multiple businesses, each with their own phone numbers. (I had discovered this on my earlier calls when the deep background man listened to me for a minute and then said, “I already explained this to you, pal.”) So Ramada tried another strategy: undercutting the competition. Initially he charged $600 to remove up to five raccoons—“that’s like a family,” he said—no matter the number of return visits; this was about a third of the going rate. Slowly, business picked up until he was averaging a raccoon a week. He abandoned the idea of a website.

“Best job I ever had,” he told me, splitting open one sunflower seed and then another. Ramada traverses the five boroughs in his van, laying traps in attics and basements; sometimes a raccoon falls through a ceiling and he must chase after it with a sack and noose. He is always on call but seldom busy, and in between jobs he cooks, walks his dog, watches Syrian news on YouTube, or— when he has the money—plays golf; sometimes a customer calls mid-round and he has to leave to deal with a raccoon. He lives in Queens with his wife, who is Italian American, and her young son, who, according to Ramada, is fond of raccoons. This is not surprising, given Ramada’s own rich and unusual affection for them.

This online adoration is at stark odds with reality, where, for the most part, we treat raccoons as pests. And not without reason: They are destructive visitors, ripping through drywall, gnawing pipes, robbing food, making noises (“whissing,” as Ramada puts it), and leaving droppings that carry a parasite which causes nausea and sometimes blindness. To deter raccoons, you can buy ultrasonic noise machines, wall spikes, and heat-activated sprinklers. You can buy urine (“100 percent pure”) from coyotes held in cages. An animal welfare activist I spoke to abhors such tactics and recommended, instead, blasting “hard rock music” in the attic. When I asked if this ever became irritating, she said: “It doesn’t bother me as much as having a raccoon gassed would bother me.” (...)

No longer consigned to the urban edge, raccoons have infiltrated New York City, occupying homes and generating steady business for people who catch them. The past five years has seen a rise in raccoon trouble—subway lines shut down, brownstones vandalized—that has become even more noticeable during the pandemic, with New Yorkers holed up indoors. Raccoons have been spotted in the West Village, on the Upper East Side, in groups of more than twenty (the collective noun is a “gaze”) among the trees of Prospect Park. In 2016, the New York Times ran a feature headlined “Raccoons Invade Brooklyn,” with tales of backyard chickens being mauled and baby raccoons, known as kits, tumbling from apartment roofs. When a tourist inquired on Reddit about where one might encounter raccoons in the city, someone responded: “Come to Queens! They’re everywhere! Just had to throw one out of my bathtub.” (...)

A Syrian immigrant in his 40s, Ramada moved to New York in the 1990s to study computer science but dropped out when he couldn’t afford tuition. Since then, he’s passed through a series of marginal jobs, from construction and fixing cars to being a cook in an Italian restaurant. About four years ago he became a trapper entirely by accident, after responding to an online advertisement that he believed was related to house painting. At the interview, Steve, the boss, asked Ramada if he knew how to climb a ladder. “I said sure,” Ramada told me. “He said, high ladder—like 40 feet.” When Ramada found out he’d be catching raccoons, he was taken aback; that Americans would pay you to remove wild animals from their houses was something he’d never imagined. Back home, he said, this would be the duty of young men—a son or a cousin looking to demonstrate his bravery. But home was here now, in this city of money and exclusion that creates its own forms of opportunity. “Sure,” he told Steve, rolling the r, and just like that he was hired.

Ramada is in his forties, with grey stubble, scruffy hair, and tobacco-stained teeth. He rolls stubby joints of cheap pot purchased from a contact in the Bronx and cruises around, lightly stoned, with his traps and the junk that fills his panel van: tools for keeping the engine going; scraps of paper with the scribbled addresses of his customers (which he otherwise forgets); husks of sunflower seeds (he says he’s addicted); and books by Naguib Mahfouz, the Egyptian Nobel laureate who published 34 novels and more than 350 short stories, nearly all of which Ramada says he has read.

I first met him in November 2019, soon after he stopped working for Steve and started his own trapping company. I had been calling raccoon trappers for days, but most of them declined to speak to me; even Steve had fobbed me off, claiming that his bosses were “at their holiday house upstate.” (It was only later, when I met Ramada, that I began piecing the story together: Steve is one of the biggest trappers in New York, and emphatically has no boss.) Another trapper spoke to me on background for 45 minutes and made me promise not to refer to a word of our conversation. Others put the phone down when they heard the word “journalist.” But Ramada, when I reached him, acted as if he’d been waiting for me to call. His accent was very different from those of the gruff New Yorkers I’d been dealing with. First, with conviction, he told me he could communicate with raccoons. Then he asked me if I could help him design a website.

He’d spent hours trying to find customers, printing business cards and creating listings on Google Maps, but his rivals were far ahead of him, often operating multiple businesses, each with their own phone numbers. (I had discovered this on my earlier calls when the deep background man listened to me for a minute and then said, “I already explained this to you, pal.”) So Ramada tried another strategy: undercutting the competition. Initially he charged $600 to remove up to five raccoons—“that’s like a family,” he said—no matter the number of return visits; this was about a third of the going rate. Slowly, business picked up until he was averaging a raccoon a week. He abandoned the idea of a website.

“Best job I ever had,” he told me, splitting open one sunflower seed and then another. Ramada traverses the five boroughs in his van, laying traps in attics and basements; sometimes a raccoon falls through a ceiling and he must chase after it with a sack and noose. He is always on call but seldom busy, and in between jobs he cooks, walks his dog, watches Syrian news on YouTube, or— when he has the money—plays golf; sometimes a customer calls mid-round and he has to leave to deal with a raccoon. He lives in Queens with his wife, who is Italian American, and her young son, who, according to Ramada, is fond of raccoons. This is not surprising, given Ramada’s own rich and unusual affection for them.

* * *

On the internet, there is an outpouring of love for raccoons, with Instagram accounts like @cutest.raccoons and @raccoonfeeds amassing hundreds of thousands of followers. Clips of pet raccoons (#trashpandas) rolling on giant hamster wheels, falling off furniture, and skirmishing with cats rack up hundreds of thousands of likes and shares. Influencer raccoon accounts come replete with merchandise and sponsored content; one of the most successful, an unusually pale raccoon named Uni, who lives in Taiwan, has been featured on BuzzFeed and People.com.This online adoration is at stark odds with reality, where, for the most part, we treat raccoons as pests. And not without reason: They are destructive visitors, ripping through drywall, gnawing pipes, robbing food, making noises (“whissing,” as Ramada puts it), and leaving droppings that carry a parasite which causes nausea and sometimes blindness. To deter raccoons, you can buy ultrasonic noise machines, wall spikes, and heat-activated sprinklers. You can buy urine (“100 percent pure”) from coyotes held in cages. An animal welfare activist I spoke to abhors such tactics and recommended, instead, blasting “hard rock music” in the attic. When I asked if this ever became irritating, she said: “It doesn’t bother me as much as having a raccoon gassed would bother me.” (...)

It is Ramada’s job to clean up after raccoons and thwart their attempts at havoc—the leaks and ruined ceilings and foul, crusted dens. Unlike some of his rivals, though, he refuses to blame the animals. “They been here in America before us,” he said. “That’s why they’re invading our home, just like we invade theirs.”

He has come to believe, too, that he is able to communicate with them, just as one might communicate with a dog. “They live in the house, so they understand our language,” he said. “So many times the raccoon can see us and we cannot see it. It’s in the trees and houses, just listening.”

And so a raccoon might hear a man speaking tenderly to his wife or children, Ramada said.

“So when I say to them I love you, they understand that.”

He has come to believe, too, that he is able to communicate with them, just as one might communicate with a dog. “They live in the house, so they understand our language,” he said. “So many times the raccoon can see us and we cannot see it. It’s in the trees and houses, just listening.”

And so a raccoon might hear a man speaking tenderly to his wife or children, Ramada said.

“So when I say to them I love you, they understand that.”

The History Behind 'One Night in Miami'

“No, Jim,” he reportedly said. “There’s this little black hotel. Let’s go over there. I want to talk to you.”

One Night in Miami, a new film from actress and director Regina King, dramatizes the hours that followed the boxer’s upset victory. Accompanied by Brown (Aldis Hodge), civil rights leader Malcolm X (Kingsley Ben-Adir) and singer-songwriter Sam Cooke (Leslie Odom Jr.), Clay (Eli Goree) headed to the Hampton House Motel, a popular establishment among black visitors to Jim Crow–era Miami. The specifics of the group’s post-fight conversation remain unknown, but the very next morning, Clay announced that he was a proud convert to the anti-integrationist Nation of Islam. Soon after, he adopted a new name: Muhammad Ali.

King’s directorial debut—based on Kemp Powers’ 2013 play of the same name—imagines the post-fight celebration as a meeting of four minds and their approach to civil rights activism. Each prominent in their respective fields, the men debate the most effective means of achieving equality for black Americans, as well as their own responsibilities as individuals of note. As Powers (who was also the writer-director of Pixar’s Soul) wrote in a 2013 essay, “This play is simply about one night, four friends and the many pivotal decisions that can happen in a single revelatory evening.”

Here’s what you need to know to separate fact from fiction in the film, which is now available through Amazon Prime Video.

Is One Night in Miami based on a true story?

In short: yes, but with extensive dramatic license, particularly in terms of the characters’ conversations.

Clay, Malcolm X, Cooke and Brown really were friends, and they did spend the night of February 25, 1964, together in Miami. Fragments of the story are scattered across various accounts, but as Powers, who also penned the film’s script, told the Miami Herald in 2018, he had trouble tracking down “more than perfunctory information” about what actually took place. Despite this challenge, Powers found himself intrigued by the idea of four ’60s icons gathering in the same room at such a pivotal point in history. “It was like discovering the Black Avengers,” he said to Deadline last year.

Powers turned the night’s events into a play, drawing on historical research to convey an accurate sense of the men’s character and views without deifying or oversimplifying them. The result, King tells the New York Times, is a “love letter” to black men that allows its lionized subjects to be “layered. They are vulnerable, they are strong, they are providers, they are sometimes putting on a mask. They are not unbreakable. They are flawed.”

In One Night in Miami’s retelling, the four friends emerge from their night of discourse with a renewed sense of purpose, each ready to take the next step in the fight against racial injustice. For Cooke, this translates to recording the hauntingly hopeful “A Change Is Gonna Come”; for Clay, it means asserting his differences from the athletes who preceded him—a declaration Damion Thomas, a sports curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), summarizes as “I’m free to be who I want to be. I’m joining the Nation of Islam, and I don’t support integration.”

The film fudges the timeline of these events (Cooke actually recorded the Bob Dylan–inspired song prior to the Liston-Clay fight) and perhaps overstates the gathering’s influence on the quartet’s lives. But its broader points about the men’s unique place in popular culture, as well as their contrasting examples of black empowerment, ring true.

As John Troutman, a music curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History (NMAH), says via email, “Cooke, Ali, Brown and Malcolm X together presented a dynamic range of new possibilities for Black Americans to engage in and reshape the national conversation.”

by Meilan Solly, Smithsonian | Read more:

Image: Bob Gomel / The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images

The Secret Forces That Squeeze and Pull Life Into Shape

Image: Alessandro Mongera and Otger Campàs, UC Santa Barbara

[ed. Not sure how 'secret' these forces are, or why the article should suggest they're some kind of emergent field of study (maybe I'm misinterpreting it). My son got his PhD studying biomolecular motors (transport processes that underlie cellular organization and reorganization) years ago. It's called bio-physics.]

Thursday, February 18, 2021

Next!

I want to tell you about a feeling I would have in my stomach before modeling castings. A frenetic energy, a fluttering that carried me each step as I would approach wherever the casting was. Sometimes it would be in the office of the brand, sometimes in a photo studio. Sometimes it would be in hotel rooms, and sometimes a casting director might invite you to a go-see, and you’d meet them, one on one. One time I found myself on my own, in my underwear, at midday on a Sunday in a casting director’s apartment, very aware of how alone I was at that moment. Most castings weren’t like this, though. For the majority of them, I was one of many. I walked everywhere, even in winter, because I wanted desperately to burn calories and because I was never sure I’d be long enough wherever I was to buy a bicycle. I’d know when I was approaching the casting because I’d start to see a few guys with pronounced cheekbones and skinny black jeans among the regular street goers. It would have started already, that pit-stomach feeling, but it would increase.

In Milan, during fashion week, the city would fill with models. There were castings seemingly everywhere, and so wherever I would turn, I’d see other models. The flutters were constant. I remember one time my agency sent me to cast for Moncler, the expensive outerwear brand. I was excited. Even though I don’t like Moncler jackets (not that I could have ever afforded them, but I thought they looked like inflated bin-liners), it was a big brand. If I could walk in their show, I thought, it would definitely mean something. Milan Fashion Week was twice a year––in pre-pandemic times––once in September showing the following year’s spring/summer collection, and once in February showing the fall/winter collection of that same year. This casting was in early February, when morning mist would hang over the canals, then clear, revealing a piercing, cloudless sky.

To be in fashion week was to be stepping into the future, a reminder that fashion existed on a speculative timescale. On that February day, when I went to cast for Moncler, I walked down a busy Milanese street, following Citymapper on my phone. I arrived at my destination, stepping through a massive doorway that opened into a courtyard. My heart sank. There was a long line snaking its way through the space. My agency had told me that Moncler was only looking to cast a few guys for its show; they already had a few booked who had done their campaign, and they had a roster of regular bookings. I thought they had given me this information as a boost: they’re only looking for a few guys, but here you are, being called for the casting. Instead, I guess they had said it as a warning. They are only looking for a few guys, and it’s a crapshoot. I couldn’t count the number of models in the line in front of me. It snaked back and forth enough times that I couldn’t get a good sense of it even if I’d tried.

I waited two hours to get into the casting itself. It was a cold day, so cold that I couldn’t read or hold my phone out because my fingers were numb. I kept my hands in my pockets, rocked back and forth in my black Doc Marten boots, and watched as my breath curled up into a little cloud of steam. The shadows of the other models traced long and skinny along the pink courtyard wall. I heard a guy behind me tell the model he’d come with that he really needed this job. The guy nodded but said nothing. But I think this could be the one, he continued. I have a good feeling about this one.

They finally called me inside. I was handed a jacket two sizes too small for me, and the second it became clear that the arms stopped somewhere midway up my wrist and I was never going to be able to zip it closed, I was told to leave. Next! I fumbled with the jacket, accidentally dropped my portfolio, and spilled a composite card on the floor. I didn’t bother to pick up. A two dimensional me looked up at the ceiling, only to be stood on by the hopeful guy from the queue. Next! We walked out into the Via Stendhal together, in silence.

The model-turned-sociologist Ashley Mears calls it “the jackpot.” That’s what we were all doing in that line, what the flutters in my stomach were. They were the judders of the gambler, my body’s version of the clammy hands of the slot-puller. Two lemons and a cherry. Fashion is about fantasy. There was a negligible chance of me getting that job for Moncler, but I still waited for two hours even after seeing the long line of models that slunk its way around the courtyard. Not enough, I went from Moncler to another casting, and another. I kept pulling the lever.

Why did I keep going to huge open castings when the probability of booking them was so slim? What was it about the dream of walking in a fashion show that was so enticing that it managed to draw us in enough to stand in the freezing cold on that Milanese street? The anthropologist Giulia Mensitieri, whose recent ethnography of Paris and Brussels-based creatives working in fashion, The Most Beautiful Job in the World: Lifting the Veil on the Fashion Industry, caused a stir throughout the industry, argues that fashion is “overexposed.” What she means is that the dream of fashion––the money, the fame, the craft, the artistry, the fabrics, the exuberance and excess––is a blinding light. It simultaneously draws you in, mothlike, while it obscures the reality of what is actually going on. The light is so bright that it washes out the edges. This, she argues, is how the fashion industry ends up being so exploitative. (...)

There are many ways to describe fashion’s excesses. It’s the toll that it takes on designers like Raf Simons, who caved under the crushing pressure of having to do six collections a year. It’s Burberry burning $37 million of product to maintain brand value. It’s the fact that the industry contributes 20 percent of the world’s global wastewater and trillions of plastic microfibers into our oceans (which then come back to us, in our salt). But the excesses are part of that blinding light, the exact thing that makes fashion so enticing. Mensitieri’s book is important for showing that these excesses provide cover for the exploitation that happens up and down the fashion chain. It’s not just the sweatshop workers in emerging market economies who are taken advantage of, she notes; it’s everyone except the tiniest minority right at the top of the fashion pyramid. It’s photographers working for a magazine for exposure, models working to pad their books and stylists to build their portfolios. All of this unpaid. It’s “unjust,” noted Karl Lagerfeld before he passed, impassive behind his dark sunglasses and untouchable position at the top.

As a model, the exploitation was fairly obvious. It was my agency charging me a $300 printing fee for a bunch of composite cards, which models take to castings and leave behind with casting directors, and another few hundred dollars for my portfolio—a plastic binder with the agency’s logo on it. It was having to pay out of pocket for test shoots early in my career to build my book, then paying more money to do them over after shaving off the facial hair, which I’d hated, that my agency had told me to grow. It was the models I knew sharing a studio apartment in outer Bushwick, with a shower curtain in the middle of the room for some privacy. (They were each charged over $1,000 monthly by their agency to live there.) (...)

The fact that you are selling your image also makes the rejections sting in a different way. To be a successful model is to commodify your likeness. You are essentially selling a product, and the product just happens to be the way you look. And while I’m sure it sucks when you sell clothes to be told repeatedly that your product isn’t quite what the customer is looking for, at least there is a sliver of comfort in knowing that there exists a clear separation between you (the salesperson) and your product. In modeling, that distinction is almost nonexistent. I could never quite get over the fact that I was handing over a com-card with a picture of my face on it, and that the “no” wasn’t a complete rejection of me, in my entirety. I started to question everything, not just my looks. The constant rejection was a very intimate way to be hollowed out.

While this never got easier, the thing that eventually broke me was one that no one warned me about, and thus I had no way of preparing for––the way the industry extracted time. I could never understand why a brand would hold an open casting to see five hundred or so models when they could have pre-selected a handful and still had ample choice? Why make us stand around in the cold all day only for a moment’s consideration? I have often wondered: How much of my time as a model did I spend actually modeling (like walking a runway or posing in front of a camera) versus chasing the dream, standing in lines waiting to be considered, or sitting in a make-up chair or draping myself on a sofa, waiting to be called?

To model was to wait. To wait for my turn to be cast, to wait on a set, to wait for the shutter-click, to wait to succeed, to make it, to see my face on a billboard, and, even more, to make rent, to pay off my debts to the agency, to simply keep going. This waiting, this never-knowing life of ellipses, is how the dream functions, and it’s the one aspect of the industry that Mensitieri doesn’t touch on. I think the pre-pandemic industry was so good at carving out great swathes of wasted time because to dream requires time. It’s in those wasted moments that we were given space to lean, ever so closely, into the dream.

In Milan, during fashion week, the city would fill with models. There were castings seemingly everywhere, and so wherever I would turn, I’d see other models. The flutters were constant. I remember one time my agency sent me to cast for Moncler, the expensive outerwear brand. I was excited. Even though I don’t like Moncler jackets (not that I could have ever afforded them, but I thought they looked like inflated bin-liners), it was a big brand. If I could walk in their show, I thought, it would definitely mean something. Milan Fashion Week was twice a year––in pre-pandemic times––once in September showing the following year’s spring/summer collection, and once in February showing the fall/winter collection of that same year. This casting was in early February, when morning mist would hang over the canals, then clear, revealing a piercing, cloudless sky.

To be in fashion week was to be stepping into the future, a reminder that fashion existed on a speculative timescale. On that February day, when I went to cast for Moncler, I walked down a busy Milanese street, following Citymapper on my phone. I arrived at my destination, stepping through a massive doorway that opened into a courtyard. My heart sank. There was a long line snaking its way through the space. My agency had told me that Moncler was only looking to cast a few guys for its show; they already had a few booked who had done their campaign, and they had a roster of regular bookings. I thought they had given me this information as a boost: they’re only looking for a few guys, but here you are, being called for the casting. Instead, I guess they had said it as a warning. They are only looking for a few guys, and it’s a crapshoot. I couldn’t count the number of models in the line in front of me. It snaked back and forth enough times that I couldn’t get a good sense of it even if I’d tried.

I waited two hours to get into the casting itself. It was a cold day, so cold that I couldn’t read or hold my phone out because my fingers were numb. I kept my hands in my pockets, rocked back and forth in my black Doc Marten boots, and watched as my breath curled up into a little cloud of steam. The shadows of the other models traced long and skinny along the pink courtyard wall. I heard a guy behind me tell the model he’d come with that he really needed this job. The guy nodded but said nothing. But I think this could be the one, he continued. I have a good feeling about this one.

They finally called me inside. I was handed a jacket two sizes too small for me, and the second it became clear that the arms stopped somewhere midway up my wrist and I was never going to be able to zip it closed, I was told to leave. Next! I fumbled with the jacket, accidentally dropped my portfolio, and spilled a composite card on the floor. I didn’t bother to pick up. A two dimensional me looked up at the ceiling, only to be stood on by the hopeful guy from the queue. Next! We walked out into the Via Stendhal together, in silence.

The model-turned-sociologist Ashley Mears calls it “the jackpot.” That’s what we were all doing in that line, what the flutters in my stomach were. They were the judders of the gambler, my body’s version of the clammy hands of the slot-puller. Two lemons and a cherry. Fashion is about fantasy. There was a negligible chance of me getting that job for Moncler, but I still waited for two hours even after seeing the long line of models that slunk its way around the courtyard. Not enough, I went from Moncler to another casting, and another. I kept pulling the lever.

***

Now, a few years removed from modeling, I’m interested in why. Why did I keep going to huge open castings when the probability of booking them was so slim? What was it about the dream of walking in a fashion show that was so enticing that it managed to draw us in enough to stand in the freezing cold on that Milanese street? The anthropologist Giulia Mensitieri, whose recent ethnography of Paris and Brussels-based creatives working in fashion, The Most Beautiful Job in the World: Lifting the Veil on the Fashion Industry, caused a stir throughout the industry, argues that fashion is “overexposed.” What she means is that the dream of fashion––the money, the fame, the craft, the artistry, the fabrics, the exuberance and excess––is a blinding light. It simultaneously draws you in, mothlike, while it obscures the reality of what is actually going on. The light is so bright that it washes out the edges. This, she argues, is how the fashion industry ends up being so exploitative. (...)

There are many ways to describe fashion’s excesses. It’s the toll that it takes on designers like Raf Simons, who caved under the crushing pressure of having to do six collections a year. It’s Burberry burning $37 million of product to maintain brand value. It’s the fact that the industry contributes 20 percent of the world’s global wastewater and trillions of plastic microfibers into our oceans (which then come back to us, in our salt). But the excesses are part of that blinding light, the exact thing that makes fashion so enticing. Mensitieri’s book is important for showing that these excesses provide cover for the exploitation that happens up and down the fashion chain. It’s not just the sweatshop workers in emerging market economies who are taken advantage of, she notes; it’s everyone except the tiniest minority right at the top of the fashion pyramid. It’s photographers working for a magazine for exposure, models working to pad their books and stylists to build their portfolios. All of this unpaid. It’s “unjust,” noted Karl Lagerfeld before he passed, impassive behind his dark sunglasses and untouchable position at the top.

As a model, the exploitation was fairly obvious. It was my agency charging me a $300 printing fee for a bunch of composite cards, which models take to castings and leave behind with casting directors, and another few hundred dollars for my portfolio—a plastic binder with the agency’s logo on it. It was having to pay out of pocket for test shoots early in my career to build my book, then paying more money to do them over after shaving off the facial hair, which I’d hated, that my agency had told me to grow. It was the models I knew sharing a studio apartment in outer Bushwick, with a shower curtain in the middle of the room for some privacy. (They were each charged over $1,000 monthly by their agency to live there.) (...)

The fact that you are selling your image also makes the rejections sting in a different way. To be a successful model is to commodify your likeness. You are essentially selling a product, and the product just happens to be the way you look. And while I’m sure it sucks when you sell clothes to be told repeatedly that your product isn’t quite what the customer is looking for, at least there is a sliver of comfort in knowing that there exists a clear separation between you (the salesperson) and your product. In modeling, that distinction is almost nonexistent. I could never quite get over the fact that I was handing over a com-card with a picture of my face on it, and that the “no” wasn’t a complete rejection of me, in my entirety. I started to question everything, not just my looks. The constant rejection was a very intimate way to be hollowed out.

While this never got easier, the thing that eventually broke me was one that no one warned me about, and thus I had no way of preparing for––the way the industry extracted time. I could never understand why a brand would hold an open casting to see five hundred or so models when they could have pre-selected a handful and still had ample choice? Why make us stand around in the cold all day only for a moment’s consideration? I have often wondered: How much of my time as a model did I spend actually modeling (like walking a runway or posing in front of a camera) versus chasing the dream, standing in lines waiting to be considered, or sitting in a make-up chair or draping myself on a sofa, waiting to be called?

To model was to wait. To wait for my turn to be cast, to wait on a set, to wait for the shutter-click, to wait to succeed, to make it, to see my face on a billboard, and, even more, to make rent, to pay off my debts to the agency, to simply keep going. This waiting, this never-knowing life of ellipses, is how the dream functions, and it’s the one aspect of the industry that Mensitieri doesn’t touch on. I think the pre-pandemic industry was so good at carving out great swathes of wasted time because to dream requires time. It’s in those wasted moments that we were given space to lean, ever so closely, into the dream.

by Barclay Bram, Guernica | Read more:

Image:Barclay Bram

[ed. My nephew Tony is a top tier model, and I've followed his career from the beginning. This seems like an eerily accurate account of some of our conversations. Despite the glamour, the fashion industry can be a brutal and extremely competitive business. Here's a famous shoot he did with Sølve Sundsbø and more at The Fashionisto.]

Texas Turtles Traumatized

My mom is retired, & she spends her winters volunteering at a sea turtle rescue center in south Texas. The cold snap is stunning the local turtles & they’re doing a lot of rescues. She sent me this photo today of the back of her Subaru. It’s *literally* turtles all the way down. ~ Lara

Wednesday, February 17, 2021

The Grizzly Maze

Timothy Treadwell was the sort of guy most Alaskans loved to hate. For starters, Treadwell was an outsider, a Californian from the weird-wacky end of the scale, a guy sporting a shock of blond hair and a backward baseball cap, with the outdoors skills you’d expect of a former Malibu cocktail waiter. Then there was the way Treadwell acted around bears. Lots of Alaskans would like to get a bear in their rifle sights; Treadwell sang and read to the grizzlies on the rugged Katmai Coast, and gave them names like Thumper, Mr. Chocolate, and Squiggle. He would walk up to a half-ton wild animal with four-inch claws and two-inch fangs, and say, “Czar, I’m so worried! I can’t find little Booble.” In Alaska, that kind of behavior makes a man stand out—and not in a good way.

Treadwell had been a fixture along the Katmai Coast for 13 years, camping out each spring and summer, alone, in the heart of bear country, deliberately seeking out the animals. He told the story of how this came about in his book, Among Grizzlies. By Treadwell’s account, he was born into a middle-class family on Long Island, New York. He wasn’t really a bad kid, but a handful. All along, he sensed a kinship with animals; he “donned imaginary wings, claws, and fangs.” As an adolescent, he did more than his share of drinking, wrecked the family car, and managed to get arrested. After high school, he left home for California, where he became “an overactive street punk without any skills, prospects, or hopes.” He slid into hard-core drug use and was plucked back from the edge by a Vietnam vet with a heart of gold, who slapped him into shape and pointed him toward Alaska and bears.

There he discovered his true purpose in life: watching over those noble and imperiled creatures. The way he told it, he had stumbled onto a peaceable kingdom where the bears seemed neither ferocious nor afraid of man—a childhood dream made real. Photos and videos document the breathtaking proximity to the animals that he was able to achieve. Not only did they not attack, but they seemed to give a collective ursine shrug and accept him as a somewhat odd-smelling and harmless hanger-on.

Crawling on all fours, singing and talking in that sort of odd, high voice normally reserved for babies and small dogs—”Hey, little bear, love you, aren’t you beautiful, that’s right, love you”—Treadwell sidled up to wild bears, his camera and video recorder whirring, and he filled notebooks with observations, scrawled in wavering schoolboy print. Some of the animals, he maintained, seemed to actually enjoy his company. A wounded bear he named Mickey slept near his tent for weeks and recovered; mother bears would leave their cubs nearby when they went off to forage as if asking him to babysit. By his own admission, he even went so far as to plant a kiss on one bear’s nose after it licked his fingers.

Treadwell had found love, so powerful it bordered on obsession. He called the objects of his affection grizzlies, but they were and are considered by Alaska biologists to be brown bears, the coastal version of the species Ursus arctos. The inland variation is commonly known in North America as grizzly (Ursus arctos horribilis). The distinction between grizzlies and brown bears is, most Alaskans would argue, the difference between pit bulls and Labrador retrievers. But Treadwell chose to call his bears grizzlies for reasons any publicist could explain, and justified it in print by rightly claiming they were the same species.

In the history of the Katmai National Park and Monument, stretching back over 85 years, not one person had been seriously mauled, let alone killed, by a bear. Still, these huge animals are far from harmless. At least twice, Treadwell was reduced to a quaking ball of nerves. In one case, witnessed from a distance by a bear-viewing guide in the mid-’90s, an older male bear who was courting a female lost his temper at Treadwell and stopped just short of knocking his head off. Another time, threatened by a bear trashing his tent, Treadwell made a radio call in a total panic to a local air service, asking for an immediate fly-out from the area.

Treadwell never carried a gun and maintained that even if firearms had been legal in the park, he still wouldn’t have carried one. Early on he swore off nonlethal means of protection, like the newly developed (and highly effective) portable electric fences, and even pepper spray. The spray he did use once, when he felt he had no other choice, hosing a bear he’d named Cupcake; he was so distressed by the bear’s apparent agony that he vowed he’d never use repellent again. Fear, he decided, wasn’t the message he wanted to send. Good intentions were the only shield he needed.

‘You’re going to get yourself killed’

At the end of each of those first few summers, Treadwell returned to Malibu. He and Jewel Palovak, his friend and co-author, put serious time into discussing how they might turn his burgeoning passion for bears into something more. Treadwell sold photos at crafts fairs, and he began doing free presentations for elementary school students.

He loved the children as much as they loved him. With his own kidlike enthusiasm, jumping up and down and having the kids repeat bear facts after him, he was a natural. What’s more, the youngsters were learning about bears, and coming to care about them too. Thus the idea of Grizzly People was born: a grass-roots, nonprofit organization with a professionally designed website, dedicated to protecting the bears, studying them and educating people. Palovak claims that Treadwell reached about 10,000 school-children a year. The letters from excited kids and grateful, impressed teachers poured in.

Not everyone approved of what he was doing. Regulations for Katmai stipulate viewing distances of no less than 50 yards for brown bears. Both Treadwell’s personal videos and professional productions featuring him document distances far closer than that, which angered and alarmed conservationists. Several local people resented this surfer boy with wraparound shades telling them what to do with their bears. As to his claims that the bears were endangered, not even the most greenie locals would go along with such an idea.

The bear science establishment disdained his methods; one researcher described Treadwell’s interaction with bears in the field as “his own private Jackass show,” a reference to the sophomoric MTV program that features a series of mindless, often death-defying stunts. Longtime state bear biologist Sterling Miller recalls admonishing Treadwell to be more cautious.

Treadwell wrote back saying that he would personally “be honored” to end up as grizzly scat—though that was not exactly the word he used. Says Miller, “Given his attitude, I believed it wouldn’t be long before he was so honored.”

Tom Walters, the plain-spoken head of bear-viewing guides at Katmai Wilderness Lodge, of which he is also a part owner, says, “I told him straight out, years ago, he was going to get himself killed.”

Strange season

Amie Huguenard saw Timothy Treadwell in Boulder, Colorado, at a slide show and lecture he gave in 1996 at the University of Colorado campus. She was smitten by his passion and commitment and later wrote to him. One thing led to another, and they became romantically involved. At the time of their first meeting, she was in her early 30s, a surgical physician’s assistant, attractive in a wholesome, fit way.

She had spent a couple of weeks with Treadwell in Alaska in the two summers before 2003. This year’s visit was different; there was an evident strain. For one thing, this late in the season—the end of September—it was a challenge to keep warm and dry while camping in the autumn rains with the first snows around the corner. Then there were the bears. Treadwell’s camp, a short distance from the shore of Upper Kaflia Lake, was on a grass-crowned knoll amid a labyrinth of tunneled trails that bears had worn through the dense brush over centuries. Treadwell called this place the Grizzly Maze. Huguenard’s anxiety at being there showed on a video that Treadwell shot; in one sequence, she sits in the brush with a female bear and cubs ten feet away. Then one bear shifts even closer. Huguenard’s face is taut and unsmiling. She wanted to pull back, not push to get so close.

She was frightened. They argued. Treadwell tried to reassure her. You can practically hear him saying, “Everything’s fine. It’s only Tabitha.” But in fact, everything wasn’t fine. Five miles away as the crow flies, bear biologist Matthias Breiter was camped out with a small party of photographers. The bear dynamics he observed were both chaotic and unusual. In a normal year, the half-mile of creek before him might have had 15 bears working for fish; this year, more than 60 showed up. The crowding led to conflict. “You’d usually see four fights a week,” says Breiter. “It was ten a day. Real, all-out fights. The level of aggression was far above normal.”

Treadwell had been a fixture along the Katmai Coast for 13 years, camping out each spring and summer, alone, in the heart of bear country, deliberately seeking out the animals. He told the story of how this came about in his book, Among Grizzlies. By Treadwell’s account, he was born into a middle-class family on Long Island, New York. He wasn’t really a bad kid, but a handful. All along, he sensed a kinship with animals; he “donned imaginary wings, claws, and fangs.” As an adolescent, he did more than his share of drinking, wrecked the family car, and managed to get arrested. After high school, he left home for California, where he became “an overactive street punk without any skills, prospects, or hopes.” He slid into hard-core drug use and was plucked back from the edge by a Vietnam vet with a heart of gold, who slapped him into shape and pointed him toward Alaska and bears.

There he discovered his true purpose in life: watching over those noble and imperiled creatures. The way he told it, he had stumbled onto a peaceable kingdom where the bears seemed neither ferocious nor afraid of man—a childhood dream made real. Photos and videos document the breathtaking proximity to the animals that he was able to achieve. Not only did they not attack, but they seemed to give a collective ursine shrug and accept him as a somewhat odd-smelling and harmless hanger-on.

Crawling on all fours, singing and talking in that sort of odd, high voice normally reserved for babies and small dogs—”Hey, little bear, love you, aren’t you beautiful, that’s right, love you”—Treadwell sidled up to wild bears, his camera and video recorder whirring, and he filled notebooks with observations, scrawled in wavering schoolboy print. Some of the animals, he maintained, seemed to actually enjoy his company. A wounded bear he named Mickey slept near his tent for weeks and recovered; mother bears would leave their cubs nearby when they went off to forage as if asking him to babysit. By his own admission, he even went so far as to plant a kiss on one bear’s nose after it licked his fingers.

Treadwell had found love, so powerful it bordered on obsession. He called the objects of his affection grizzlies, but they were and are considered by Alaska biologists to be brown bears, the coastal version of the species Ursus arctos. The inland variation is commonly known in North America as grizzly (Ursus arctos horribilis). The distinction between grizzlies and brown bears is, most Alaskans would argue, the difference between pit bulls and Labrador retrievers. But Treadwell chose to call his bears grizzlies for reasons any publicist could explain, and justified it in print by rightly claiming they were the same species.

In the history of the Katmai National Park and Monument, stretching back over 85 years, not one person had been seriously mauled, let alone killed, by a bear. Still, these huge animals are far from harmless. At least twice, Treadwell was reduced to a quaking ball of nerves. In one case, witnessed from a distance by a bear-viewing guide in the mid-’90s, an older male bear who was courting a female lost his temper at Treadwell and stopped just short of knocking his head off. Another time, threatened by a bear trashing his tent, Treadwell made a radio call in a total panic to a local air service, asking for an immediate fly-out from the area.

Treadwell never carried a gun and maintained that even if firearms had been legal in the park, he still wouldn’t have carried one. Early on he swore off nonlethal means of protection, like the newly developed (and highly effective) portable electric fences, and even pepper spray. The spray he did use once, when he felt he had no other choice, hosing a bear he’d named Cupcake; he was so distressed by the bear’s apparent agony that he vowed he’d never use repellent again. Fear, he decided, wasn’t the message he wanted to send. Good intentions were the only shield he needed.

‘You’re going to get yourself killed’

At the end of each of those first few summers, Treadwell returned to Malibu. He and Jewel Palovak, his friend and co-author, put serious time into discussing how they might turn his burgeoning passion for bears into something more. Treadwell sold photos at crafts fairs, and he began doing free presentations for elementary school students.

He loved the children as much as they loved him. With his own kidlike enthusiasm, jumping up and down and having the kids repeat bear facts after him, he was a natural. What’s more, the youngsters were learning about bears, and coming to care about them too. Thus the idea of Grizzly People was born: a grass-roots, nonprofit organization with a professionally designed website, dedicated to protecting the bears, studying them and educating people. Palovak claims that Treadwell reached about 10,000 school-children a year. The letters from excited kids and grateful, impressed teachers poured in.

Not everyone approved of what he was doing. Regulations for Katmai stipulate viewing distances of no less than 50 yards for brown bears. Both Treadwell’s personal videos and professional productions featuring him document distances far closer than that, which angered and alarmed conservationists. Several local people resented this surfer boy with wraparound shades telling them what to do with their bears. As to his claims that the bears were endangered, not even the most greenie locals would go along with such an idea.

The bear science establishment disdained his methods; one researcher described Treadwell’s interaction with bears in the field as “his own private Jackass show,” a reference to the sophomoric MTV program that features a series of mindless, often death-defying stunts. Longtime state bear biologist Sterling Miller recalls admonishing Treadwell to be more cautious.

Treadwell wrote back saying that he would personally “be honored” to end up as grizzly scat—though that was not exactly the word he used. Says Miller, “Given his attitude, I believed it wouldn’t be long before he was so honored.”

Tom Walters, the plain-spoken head of bear-viewing guides at Katmai Wilderness Lodge, of which he is also a part owner, says, “I told him straight out, years ago, he was going to get himself killed.”

Strange season

Amie Huguenard saw Timothy Treadwell in Boulder, Colorado, at a slide show and lecture he gave in 1996 at the University of Colorado campus. She was smitten by his passion and commitment and later wrote to him. One thing led to another, and they became romantically involved. At the time of their first meeting, she was in her early 30s, a surgical physician’s assistant, attractive in a wholesome, fit way.

She had spent a couple of weeks with Treadwell in Alaska in the two summers before 2003. This year’s visit was different; there was an evident strain. For one thing, this late in the season—the end of September—it was a challenge to keep warm and dry while camping in the autumn rains with the first snows around the corner. Then there were the bears. Treadwell’s camp, a short distance from the shore of Upper Kaflia Lake, was on a grass-crowned knoll amid a labyrinth of tunneled trails that bears had worn through the dense brush over centuries. Treadwell called this place the Grizzly Maze. Huguenard’s anxiety at being there showed on a video that Treadwell shot; in one sequence, she sits in the brush with a female bear and cubs ten feet away. Then one bear shifts even closer. Huguenard’s face is taut and unsmiling. She wanted to pull back, not push to get so close.

She was frightened. They argued. Treadwell tried to reassure her. You can practically hear him saying, “Everything’s fine. It’s only Tabitha.” But in fact, everything wasn’t fine. Five miles away as the crow flies, bear biologist Matthias Breiter was camped out with a small party of photographers. The bear dynamics he observed were both chaotic and unusual. In a normal year, the half-mile of creek before him might have had 15 bears working for fish; this year, more than 60 showed up. The crowding led to conflict. “You’d usually see four fights a week,” says Breiter. “It was ten a day. Real, all-out fights. The level of aggression was far above normal.”

by Nick Jans, Reader's Digest | Read more:

Image: Willy Fulton

Joni Mitchell

Listening to these bare-bones sketches, I suddenly understood how the sonic and harmonic ambition of that record wasn’t surface-level affectation but written into the fabric of the songs themselves from the start. Hissing’s complexity wasn’t just 1970s excess, it was a masterpiece of word, sound and thought in Swiss-watch alignment. (...)

Discovering Prince was an obsessive Joni fan – covering her, writing her into his lyrics, unsuccessfully pitching songs to her – blew the whole issue out of the water. Who needs the white rock canon, anyway? Not Joni, for one. Given she was as close musically and personally to Charles Mingus and Herbie Hancock as to Bob Dylan or Carly Simon, isn’t it great that her lineage can be traced through Prince, Chaka Khan and Kate Bush to Outkast, Frank Ocean, James Blake?

Joni Mitchell: how rock misogyny made me into a militant fan (Joe Muggs, The Guardian)

Discovering Prince was an obsessive Joni fan – covering her, writing her into his lyrics, unsuccessfully pitching songs to her – blew the whole issue out of the water. Who needs the white rock canon, anyway? Not Joni, for one. Given she was as close musically and personally to Charles Mingus and Herbie Hancock as to Bob Dylan or Carly Simon, isn’t it great that her lineage can be traced through Prince, Chaka Khan and Kate Bush to Outkast, Frank Ocean, James Blake?

Joni Mitchell: how rock misogyny made me into a militant fan (Joe Muggs, The Guardian)

[ed. From: “The Hissing of Summer Lawns” Demos released recently. Just a guitar and piano.]

Coronavirus: Links, Discussion, Open Thread

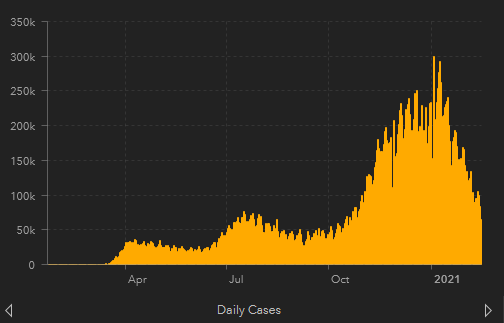

So far there have been three waves of coronavirus cases in the US. The first wave was the beginning, when it caught us unprepared. The second wave was in July, when we got sloppy and lifted lockdowns too soon. The third wave was November through January, because the coronavirus is seasonal and winter is its season (also probably the holidays). From Johns Hopkins CRC:

A fourth wave may hit in March, when the more contagious B117 strain from the UK takes over. Expect more shelter-in-place orders, school shutdowns, and a spike in cases at least the size of July's, maybe December's. That will last until May-ish, when the usual control system (more virus -> stricter lockdowns -> less virus -> looser lockdowns -> more virus) moves back into the "less virus" stage. Also coronavirus is seasonal and summer isn't its season. Also by that time a decent chunk of the population will be vaccinated. The worst consequences of the UK strain should burn themselves out by late spring.

A fourth wave may hit in March, when the more contagious B117 strain from the UK takes over. Expect more shelter-in-place orders, school shutdowns, and a spike in cases at least the size of July's, maybe December's. That will last until May-ish, when the usual control system (more virus -> stricter lockdowns -> less virus -> looser lockdowns -> more virus) moves back into the "less virus" stage. Also coronavirus is seasonal and summer isn't its season. Also by that time a decent chunk of the population will be vaccinated. The worst consequences of the UK strain should burn themselves out by late spring.

Prediction: 75% chance that there will be a new wave peaking in March or April, with a peak at least half again as high as the preceding trough.

[EDIT: some people link new studies saying the B117 strain is less virulent than previously believed, and the US has been getting much better at vaccination since I checked, probably my prediction above is too high and we should worry less about this]

We should also be concerned about a fifth wave (possibly overlapping with the fourth wave; they may not have obviously separate peaks). Virologists have identified two new strains, one in South Africa, one in Brazil, which probably have "immune escape" - the ability to infect people who have already gotten, recovered from, and developed antibodies to the original strain (or been vaccinated against it). Both strains already have a few cases in the US. It will take them a few months to spread to the point where they're relevant, but they should eventually be the majority of new cases.

[EDIT: some people link new studies saying the B117 strain is less virulent than previously believed, and the US has been getting much better at vaccination since I checked, probably my prediction above is too high and we should worry less about this]

We should also be concerned about a fifth wave (possibly overlapping with the fourth wave; they may not have obviously separate peaks). Virologists have identified two new strains, one in South Africa, one in Brazil, which probably have "immune escape" - the ability to infect people who have already gotten, recovered from, and developed antibodies to the original strain (or been vaccinated against it). Both strains already have a few cases in the US. It will take them a few months to spread to the point where they're relevant, but they should eventually be the majority of new cases.

Prediction: 66% chance that sometime this year, the South African and Brazilian strains - or other new strains with similar dynamics - will be a majority of coronavirus cases in the US.

Some sources describe these strains as "vaccine resistant". This is a matter of degree. The UK strain is probably very slightly vaccine-resistant (most sources are describing it as not vaccine resistant, but if you look closely this is another "well we can't prove it is" situation, and the best point estimates suggest some tiny amount of extra resistance which probably doesn't make a big difference.). The South African strain is significantly vaccine resistant. The Brazilian strain is too new to know much about, but seems to be very similar to the South African strain and I would be surprised if its numbers differed very much.

In terms of preventing sympomatic infections, the best current data suggests that the Novavax vaccine is 96% effective against Coronavirus Classic, 86% effective against UK, and 60% effective against South Africa. AstraZeneca is something like 80% effective against Classic, 65% effective against UK, and the South African study was kind of bungled but our best guess is "seems pretty bad". Johnson and Johnson is 66-72%+ effective against Classic and 57% effective against South Africa. Pfizer/Moderna hasn't been tested against South Africa in real life yet, but lab studies suggest slightly decreased efficacy.

The good news is that vaccines which protect inconsistently against infection are probably still good at protecting against severe disease and death. For example, although the J&J vaccine is only 66-72% effective at preventing people from getting symptomatic disease, it's 85% effective at preventing severe disease, and (at least so far in studies) 100% effective at preventing deaths. In fact, most vaccine studies have shown 100% efficacy at preventing deaths. Probably some of this is that the trials are underpowered to detect rare outcomes, but the vaccines really do seem good at this, even with strains that have some level of vaccine resistance. Also, although I don't know of any studies investigating this, it makes sense to think that vaccinated people would also be less likely to transmit the virus to others if they do get it.

Some sources describe these strains as "vaccine resistant". This is a matter of degree. The UK strain is probably very slightly vaccine-resistant (most sources are describing it as not vaccine resistant, but if you look closely this is another "well we can't prove it is" situation, and the best point estimates suggest some tiny amount of extra resistance which probably doesn't make a big difference.). The South African strain is significantly vaccine resistant. The Brazilian strain is too new to know much about, but seems to be very similar to the South African strain and I would be surprised if its numbers differed very much.

In terms of preventing sympomatic infections, the best current data suggests that the Novavax vaccine is 96% effective against Coronavirus Classic, 86% effective against UK, and 60% effective against South Africa. AstraZeneca is something like 80% effective against Classic, 65% effective against UK, and the South African study was kind of bungled but our best guess is "seems pretty bad". Johnson and Johnson is 66-72%+ effective against Classic and 57% effective against South Africa. Pfizer/Moderna hasn't been tested against South Africa in real life yet, but lab studies suggest slightly decreased efficacy.

The good news is that vaccines which protect inconsistently against infection are probably still good at protecting against severe disease and death. For example, although the J&J vaccine is only 66-72% effective at preventing people from getting symptomatic disease, it's 85% effective at preventing severe disease, and (at least so far in studies) 100% effective at preventing deaths. In fact, most vaccine studies have shown 100% efficacy at preventing deaths. Probably some of this is that the trials are underpowered to detect rare outcomes, but the vaccines really do seem good at this, even with strains that have some level of vaccine resistance. Also, although I don't know of any studies investigating this, it makes sense to think that vaccinated people would also be less likely to transmit the virus to others if they do get it.

Prediction: 55% chance that later, when we have great evidence on this, we’ll find that P/M, Novavax, AZ, and J&J all cut deaths from all extant strains by at least four-fifths.

When the fifth wave strikes in late spring/early summer, some of the population (~50%?) will be vaccinated, another part of the population (~25%?) will have had the disease already, and the rest (~25%?) will be completely vulnerable. The new strains will probably cause a limited number of mild cases among the vaccinated/resistant, and a larger number of more severe cases among the vulnerable. Either way, the presence of the larger vaccinated/resistant contingent could potentially make this less severe than previous waves. Also, we may have learned more about treating severe COVID (with eg ivermectin, fluvoxamine), which might further decrease deaths. (...)

R in most US states right now is closely clustered around 1. Mutant strains are more contagious, enough to bring the R0 up to 1.5 or so. But having a lot of the population vaccinated will bring it back down again. Also, I'm acting like there's some complex-yet-illuminating calculation we can do here, but realistically none of this matters. It's not a coincidence that all US states are closely clustered around 1. It's the control system again - whenever things look good, we relax restrictions (both legally and in terms of personal behavior) until they look bad again, then backpedal and tighten restrictions. So we oscillate between like 0.8 and 1.2 (I made those numbers up, I don't know the real ones). If vaccines made R0 go to 0.5 or whatever, we would loosen some restrictions until it was back at 1 again. So unless we overwhelm the control system, R0 will hover around 1 in the summer too, and the only question is how strict our lockdowns will be.

In autumn, if we haven’t already vaccinated everyone there’s a risk things will get worse again because of the seasonal effect. Also, for all we know maybe the virus will have mutated even further and become even more vaccine resistant. Now what?

Vaccine companies say it should be pretty easy to create a vaccine targeted to the South African strain. Remember, it only took them two days to invent the original coronavirus vaccine. This one should be even easier, since we already know the principles involved. The vaccine is basically taking a part of the coronavirus' chemical code which functions as a "password" and telling it to the immune system so it can break its password and defeat it. The mutant coronaviruses haven't done anything fancy, they've just changed their password. The vaccine companies can plug in the new password to the vaccines they already have, and they'll work against the mutant strains.

But even if they have it tomorrow, that's...what? Another four months for studies, one month before the FDA is able to meet to discuss an approval (you can't rush meetings!), two months to ramp up production, and five months of Distribution Hell while we argue about who should be first in line and prosecute people for distributing vaccines too quickly. So maybe by this time next year you get a vaccine against the South African strain. And by that point the virus will have just changed its password again and we'll be right back where we started.

The problem is, all the virus has to do is change its chemical "password" - a simple one-step process. The people fighting the virus have to go through the entire FDA approval, production, and distribution pipeline each time - a seven million step process. This puts us at a bit of a handicap.

Best-case scenario, here's how we respond:

When the fifth wave strikes in late spring/early summer, some of the population (~50%?) will be vaccinated, another part of the population (~25%?) will have had the disease already, and the rest (~25%?) will be completely vulnerable. The new strains will probably cause a limited number of mild cases among the vaccinated/resistant, and a larger number of more severe cases among the vulnerable. Either way, the presence of the larger vaccinated/resistant contingent could potentially make this less severe than previous waves. Also, we may have learned more about treating severe COVID (with eg ivermectin, fluvoxamine), which might further decrease deaths. (...)

R in most US states right now is closely clustered around 1. Mutant strains are more contagious, enough to bring the R0 up to 1.5 or so. But having a lot of the population vaccinated will bring it back down again. Also, I'm acting like there's some complex-yet-illuminating calculation we can do here, but realistically none of this matters. It's not a coincidence that all US states are closely clustered around 1. It's the control system again - whenever things look good, we relax restrictions (both legally and in terms of personal behavior) until they look bad again, then backpedal and tighten restrictions. So we oscillate between like 0.8 and 1.2 (I made those numbers up, I don't know the real ones). If vaccines made R0 go to 0.5 or whatever, we would loosen some restrictions until it was back at 1 again. So unless we overwhelm the control system, R0 will hover around 1 in the summer too, and the only question is how strict our lockdowns will be.

In autumn, if we haven’t already vaccinated everyone there’s a risk things will get worse again because of the seasonal effect. Also, for all we know maybe the virus will have mutated even further and become even more vaccine resistant. Now what?

Vaccine companies say it should be pretty easy to create a vaccine targeted to the South African strain. Remember, it only took them two days to invent the original coronavirus vaccine. This one should be even easier, since we already know the principles involved. The vaccine is basically taking a part of the coronavirus' chemical code which functions as a "password" and telling it to the immune system so it can break its password and defeat it. The mutant coronaviruses haven't done anything fancy, they've just changed their password. The vaccine companies can plug in the new password to the vaccines they already have, and they'll work against the mutant strains.

But even if they have it tomorrow, that's...what? Another four months for studies, one month before the FDA is able to meet to discuss an approval (you can't rush meetings!), two months to ramp up production, and five months of Distribution Hell while we argue about who should be first in line and prosecute people for distributing vaccines too quickly. So maybe by this time next year you get a vaccine against the South African strain. And by that point the virus will have just changed its password again and we'll be right back where we started.

The problem is, all the virus has to do is change its chemical "password" - a simple one-step process. The people fighting the virus have to go through the entire FDA approval, production, and distribution pipeline each time - a seven million step process. This puts us at a bit of a handicap.

Best-case scenario, here's how we respond:

by Scott Alexander, Astral Codex Ten | Read more:

Image: Johns Hopkins

30 by 30: Send Your Ideas

'America, send us your ideas': Biden pledges to protect 30% of US lands by 2030 (The Guardian)

Image: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Tuesday, February 16, 2021

Vince Taylor and His Playboys

[ed. Brand New Cadillac. Clash version here.]

Trading in Atoms For Bits

All forms of exchange necessarily depend on differences in voltage.

—Fernand Braudel

The history of digital cash consists of scientific discoveries from the 1970s, hardware from the 1980s, and networks from the 1990s, shaped by theories from the previous three centuries and beliefs about the next ten thousand years. It speaks ancient ideas with a modern twang, as we might when we say “quid pro quo” or “shibboleth”: the sovereign right to issue money, the debasement of coinage, the symbolic stamp that transfers the rights to value from me to thee. Digital cash has the hovering, unsettled realness (not reality) of all money, a matter of life and death that is also symbolic tokens, rules of a game, scraps of cotton blend and polymer, entries in a database, promises made and broken, gestures of affection and trust. The long history we are discussing here is at its heart the history of a debate about knowledge, an epistemological argument conducted through technologies.