Wednesday, September 30, 2020

Tuesday, September 29, 2020

The Love That Lays the Swale in Rows

If that sounds naive or hopeless, it’s because we have been misled by a metaphor. We’ve defined our relation with technology not as that of body and limb or even that of sibling and sibling but as that of master and slave. The idea goes way back. It took hold at the dawn of Western philosophical thought, emerging first with the ancient Athenians. Aristotle, in discussing the operation of households at the beginning of his Politics, argued that slaves and tools are essentially equivalent, the former acting as “animate instruments” and the latter as “inanimate instruments” in the service of the master of the house. If tools could somehow become animate, Aristotle posited, they would be able to substitute directly for the labor of slaves. “There is only one condition on which we can imagine managers not needing subordinates, and masters not needing slaves,” he mused, anticipating the arrival of computer automation and even machine learning. “This condition would be that each [inanimate] instrument could do its own work, at the word of command or by intelligent anticipation.” It would be “as if a shuttle should weave itself, and a plectrum should do its own harp-playing.”

The conception of tools as slaves has colored our thinking ever since. It informs society’s recurring dream of emancipation from toil. “All unintellectual labour, all monotonous, dull labour, all labour that deals with dreadful things, and involves unpleasant conditions, must be done by machinery,” wrote Oscar Wilde in 1891. “On mechanical slavery, on the slavery of the machine, the future of the world depends.” John Maynard Keynes, in a 1930 essay, predicted that mechanical slaves would free humankind from “the struggle for subsistence” and propel us to “our destination of economic bliss.” In 2013, Mother Jones columnist Kevin Drum declared that “a robotic paradise of leisure and contemplation eventually awaits us.” By 2040, he forecast, our computer slaves—“they never get tired, they’re never ill-tempered, they never make mistakes”—will have rescued us from labor and delivered us into a new Eden. “Our days are spent however we please, perhaps in study, perhaps playing video games. It’s up to us.”

With its roles reversed, the metaphor also informs society’s nightmares about technology. As we become dependent on our technological slaves, the thinking goes, we turn into slaves ourselves. From the eighteenth century on, social critics have routinely portrayed factory machinery as forcing workers into bondage. “Masses of labourers,” wrote Marx and Engels in their Communist Manifesto, “are daily and hourly enslaved by the machine.” Today, people complain all the time about feeling like slaves to their appliances and gadgets. “Smart devices are sometimes empowering,” observed The Economist in “Slaves to the Smartphone,” an article published in 2012. “But for most people the servant has become the master.” More dramatically still, the idea of a robot uprising, in which computers with artificial intelligence transform themselves from our slaves to our masters, has for a century been a central theme in dystopian fantasies about the future. The very word “robot,” coined by a science fiction writer in 1920, comes from robota, a Czech term for servitude.

The master-slave metaphor, in addition to being morally fraught, distorts the way we look at technology. It reinforces the sense that our tools are separate from ourselves, that our instruments have an agency independent of our own. We start to judge our technologies not on what they enable us to do but rather on their intrinsic qualities as products—their cleverness, their efficiency, their novelty, their style. We choose a tool because it’s new or it’s cool or it’s fast, not because it brings us more fully into the world and expands the ground of our experiences and perceptions. We become mere consumers of technology.

The metaphor encourages society to take a simplistic and fatalistic view of technology and progress. If we assume that our tools act as slaves on our behalf, always working in our best interest, then any attempt to place limits on technology becomes hard to defend. Each advance grants us greater freedom and takes us a stride closer to, if not utopia, then at least the best of all possible worlds. Any misstep, we tell ourselves, will be quickly corrected by subsequent innovations. If we just let progress do its thing, it will find remedies for the problems it creates. “Technology is not neutral but serves as an overwhelming positive force in human culture,” writes one pundit, expressing the self-serving Silicon Valley ideology that in recent years has gained wide currency. “We have a moral obligation to increase technology because it increases opportunities.” The sense of moral obligation strengthens with the advance of automation, which, after all, provides us with the most animate of instruments, the slaves that, as Aristotle anticipated, are most capable of releasing us from our labors.

The belief in technology as a benevolent, self-healing, autonomous force is seductive. It allows us to feel optimistic about the future while relieving us of responsibility for that future. It particularly suits the interests of those who have become extraordinarily wealthy through the labor-saving, profit-concentrating effects of automated systems and the computers that control them. It provides our new plutocrats with a heroic narrative in which they play starring roles: job losses may be unfortunate, but they’re a necessary evil on the path to the human race’s eventual emancipation by the computerized slaves that our benevolent enterprises are creating. Peter Thiel, a successful entrepreneur and investor who has become one of Silicon Valley’s most prominent thinkers, grants that “a robotics revolution would basically have the effect of people losing their jobs.” But, he hastens to add, “it would have the benefit of freeing people up to do many other things.” Being freed up sounds a lot more pleasant than being fired.

There’s a callousness to such grandiose futurism. As history reminds us, high-flown rhetoric about using technology to liberate workers often masks a contempt for labor. It strains credulity to imagine today’s technology moguls, with their libertarian leanings and impatience with government, agreeing to the kind of vast wealth-redistribution scheme that would be necessary to fund the self-actualizing leisure-time pursuits of the jobless multitudes. Even if society were to come up with some magic spell, or magic algorithm, for equitably parceling out the spoils of automation, there’s good reason to doubt whether anything resembling the “economic bliss” imagined by Keynes would ensue.

In a prescient passage in The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt observed that if automation’s utopian promise were actually to pan out, the result would probably feel less like paradise than like a cruel practical joke. The whole of modern society, she wrote, has been organized as “a laboring society,” where working for pay, and then spending that pay, is the way people define themselves and measure their worth. Most of the “higher and more meaningful activities” revered in the distant past have been pushed to the margin or forgotten, and “only solitary individuals are left who consider what they are doing in terms of work and not in terms of making a living.” For technology to fulfill humankind’s abiding “wish to be liberated from labor’s ‘toil and trouble’ ” at this point would be perverse. It would cast us deeper into a purgatory of malaise. What automation confronts us with, Arendt concluded, “is the prospect of a society of laborers without labor, that is, without the only activity left to them. Surely, nothing could be worse.” Utopianism, she understood, is a form of self-delusion.

Writing a Book: Is It Worth It?

To me, the success of this book was totally unexpected: while I was writing it, I thought that it was going to be a bit niche, and I set myself the goal of selling 10,000 copies over the lifetime of the book. Having passed that goal tenfold, this seems like a good opportunity to look back and reflect on the process. I don’t want to make this post too self-congratulatory, but rather I will try to share some insights into the business of book-writing.

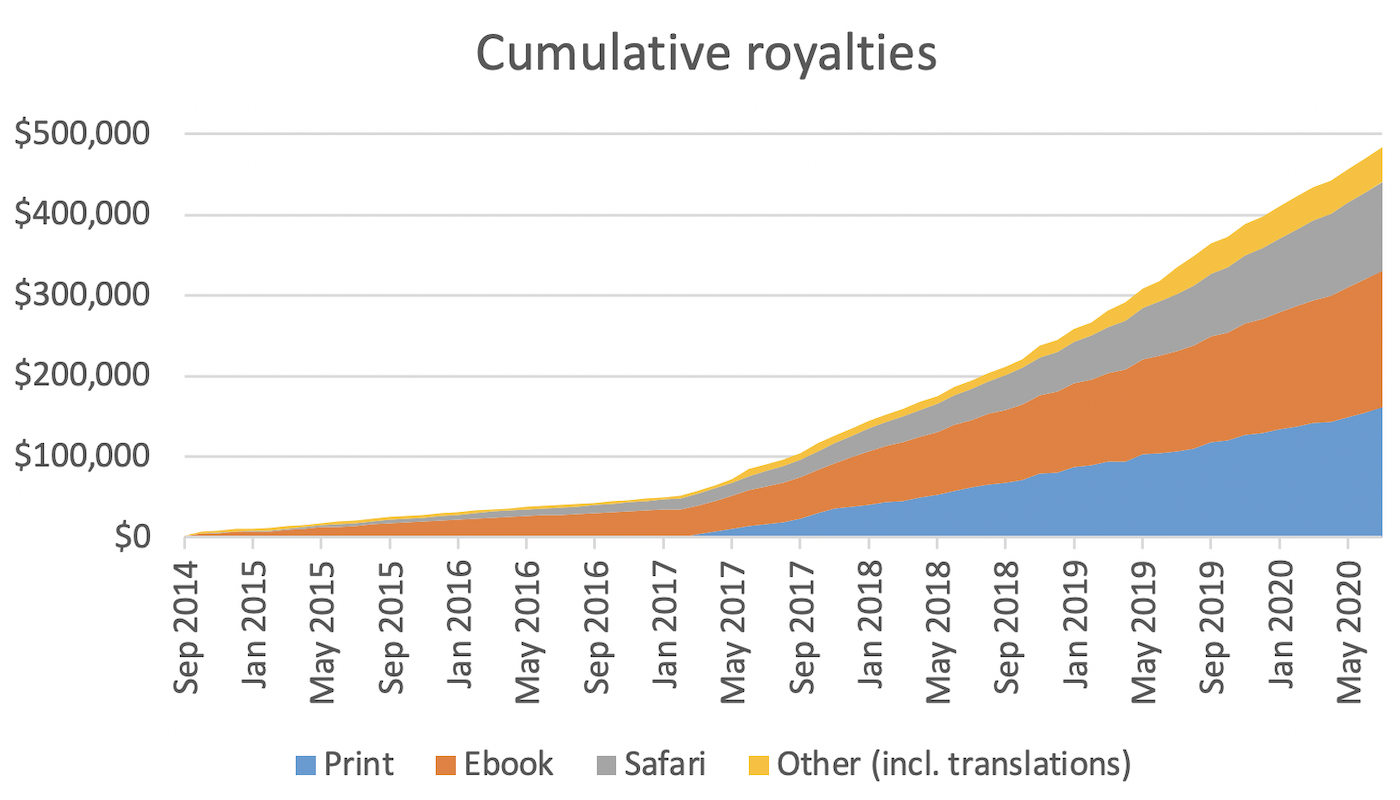

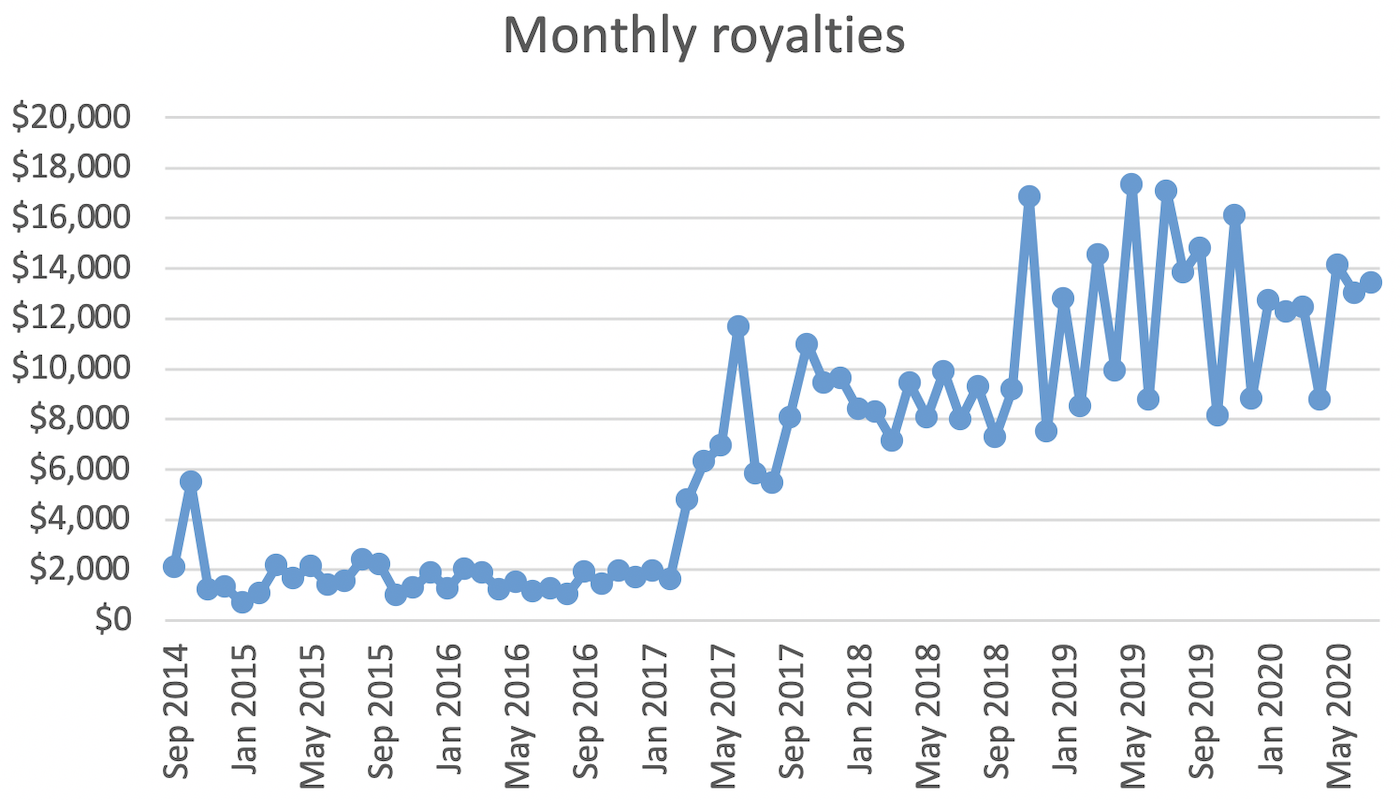

For the first 2½ years the book was in “early release”: during this period I was still writing, and we released it in unedited form, one chapter at a time, as ebook only. Then in March 2017 the book was officially published, and the print edition went on sale. Since then, the sales have fluctuated from month to month, but on average they have stayed remarkably constant. At some point I would expect the market to become saturated (i.e. most people who were going to buy the book have already bought it), but that does not seem to have happened yet: indeed, sales noticeably increased in late 2018 (I don’t know why). The x axis ends in July 2020 because from the time of sale, it takes a couple of months for the money to trickle through the system.

My contract with the publisher specifies that I get 25% of publisher revenue from ebooks, online access, and licensing, 10% of revenue from print sales, and 5% of revenue from translations. That’s a percentage of the wholesale price that retailers/distributors pay to the publisher, so it doesn’t include the retailers’ markup. The figures in this section are the royalties I was paid, after the retailer and publisher have taken their cut, but before tax.

The total sales since the beginning have been (in US dollars):

- Print: 68,763 copies, $161,549 royalties ($2.35/book)

- Ebook: 33,420 copies, $169,350 royalties ($5.07/book)

- O’Reilly online access (formerly called Safari Books Online): $110,069 royalties (I don’t get readership numbers for this channel)

- Translations: 5,896 copies, $8,278 royalties ($1.40/book)

- Other licensing and sponsorship: $34,600 royalties

- Total: 108,079 copies, $477,916

Now, in retrospect, it turns out that those 2.5 years were a good investment, because the income that this work has generated is in the same ballpark as the Silicon Valley software engineering salary (including stock and benefits) I could have received in the same time if I hadn’t quit LinkedIn in 2014 to work on the book. But of course I didn’t know that at the time! The royalties could easily have turned out to be a factor of 10 lower, in which case it would have been a financially much less compelling proposition.

by Martin Kleppmann | Read more:

Images: Martin Kleppmann

Social Cooling

Big Data is supercharging this effect.

This could limit your desire to take risks or exercise free speech.

Over the long term these 'chilling effects' could 'cool down' society.

[ed. Comments (Hacker News).]

Monday, September 28, 2020

Antidote to COVID-19 Science Overload

The wall-to-wall coverage has eased since then, but the pace of discovery hasn’t. Every day, hundreds of new research papers are published or posted about the virus and pandemic, ranging from case studies of single patients to randomized, controlled trials of potential treatments.

It’s a fire hose of information that overwhelms even the most fervent COVID-19 science junkies.

But there’s a way to keep current without having to spend your days and nights clicking through journal websites. For the past five months, a small group of faculty and students at the University of Washington has been wading through the deluge so you don’t have to. Five days a week, the Alliance for Pandemic Preparedness produces the “COVID-19 Literature Situation Report,” which provides a succinct summary of key scientific developments.

It’s a quick read and mostly jargon-free in keeping with a target audience that includes not only public health officials, but also politicians, community leaders and the general public. The group also prepares occasional in-depth reports about issues of pressing interest, like the long-term health effects of COVID-19.

The project started as an effort by staff at the Washington Department of Health (DOH) to keep up with rapid-fire developments early in the outbreak. But the agency was stretched too thin and contracted with Guthrie and his colleagues to continue and expand the work.

Their initial distribution list was 40 people. Today, about 1,600 subscribers get the email newsletter, many of whom share it via other websites and online bulletin boards. Guthrie has heard from readers at the CDC and top universities around the country. Members of Gov. Jay Inslee’s staff are on the distribution list.

Producing what the team calls the “LitRep” is a daily deadline dance that starts at 6 a.m. and doesn’t end until Guthrie or his co-leader Dr. Jennifer Ross, an infectious disease specialist at UW Medicine, hit the “send” button about 12 hours later.

Much of the work is done by a rotating group of five students — mostly doctoral candidates in global health or epidemiology — who work in shifts on a kind of virtual assembly line.

The early birds gather the raw materials, using standard search terms to pull all the new studies posted on PubMed, a free government search engine, and medRxiv and bioRxiv, which posts preprints before peer review. They also manually check several high-profile journals, including the Lancet and the New England Journal of Medicine.

“It’s a very distilled version,” said Brandon Guthrie, assistant professor of global health and epidemiology and co-leader of the effort. “What are the most important things (we) need to know that are coming out today?” (...)

The average haul is about 400 papers a day but can range between 200 and 1,000, said Lorenzo Tolentino, who just finished his master’s degree at the UW Department of Global Health and was one of the first students to sign on for the project.

Image: Greg Gilbert / The Seattle Times

Signs of the Times

The family whose Black Lives Matter sign shook their conservative town (The Guardian); and, ‘Trump Street’ starts a bitter fight over political signs, and much more, in the Alaska town of Eagle (Anchorage Daily News)

Sunday, September 27, 2020

How Work Became an Inescapable Hellhole

I get out of bed and yell at Alexa a few times to turn on NPR. I turn on the shower. As it warms up, I check Slack to see if there’s anything I need to attend to as the East Coast wakes up. When I get out of the shower, the radio’s playing something interesting, so while I’m standing there in my towel, I look it up online and tweet it. I get dressed and get my coffee and sit down at the computer, where I spend a solid hour and a half reading things, tweeting things, and waiting for them to get fav’ed. I post one of the stories I read to the Facebook page of 43,000 followers that I’ve been running for a decade. I check back in five minutes to see if anyone’s commented on it. I tell myself I should try to get to work while forgetting this is kind of my work.

I think, I should really start writing. I go to the Google Doc draft open in my browser. Oops, I mean I go to the clothing website to see if the thing I put in my cart last week is on sale. Oops, I actually mean I go back to Slack to drop in a link to make sure everyone knows I’m online and working. I write 200 words in my draft before deciding I should sign that contract for a speaking engagement that’s been sitting in my Inbox of Shame. I don’t have a printer or scanner, and I can’t remember the password for the online document signer. I try to reset the password but it says, quite nicely, that I can’t use any of my last three passwords. Someone is calling with a Seattle area code; they don’t leave a message because my voicemail is full and has been for six months.

I’m in my email and the “Promotions” tab has somehow grown from two to 42 over the course of three hours. The unsubscribe widget I installed a few months ago stopped working when the tech people at work made everyone change their passwords, and now I spend a lot of time deleting emails from West Elm. But wait there’s a Facebook notification: A new post in the group page for the dog rescue where I adopted my puppy! Someone I haven’t spoken to directly since high school has posted something new!

Over on LinkedIn, my book agent is celebrating her fifth work anniversary; so is a former student whose face I vaguely remember. I have lunch and hate-skim a blog I’ve been hate-skimming for years. Trump does a bad tweet. Someone else wrote a bad take. I eke out some more writing between very important-seeming Slack conversations about Joe Jonas’ musculature.

I go on a walk. I get interrupted once, twice, 15 times by one of my group texts. I get home and go to the bathroom, where I have just enough time to look at my phone again. I drive to the grocery store and get stuck at a long stoplight. I pick up my phone, which says, “It looks like you are driving.” I lie to my phone.

I’m checking out at the grocery store and I’m checking email. I’m getting into the car to drive home and I’m texting my friend an inside joke. I’m five minutes from home and I’m checking in with my boyfriend. I’m back at home with a beer and sitting in the backyard and “relaxing” by reading the internet and tweeting and finalizing edits on a piece. I’m texting my mom instead of calling her. I’m posting a dog walk photo to Instagram and wondering if I’ve posted too many dog photos lately. I’m making dinner while asking Alexa to play a podcast where people talk about the news I didn’t really internalize.

I get into bed with the best intention of reading the book on my nightstand but wow, that’s a really funny TikTok. I check my Instagram likes on the dog photo I did indeed post. I check my email and my other email and Facebook. There’s nothing else to check, so somehow I decide it’s a good time to open my Delta app and check on my frequent flyer mile count. Oops, I ran out of book time; better set SleepCycle.

I’m equally ashamed and exhausted writing that description of a pretty standard day in my digital life—and it doesn’t even include all of the additional times I looked at my phone, or checked social media, or went back and forth between a draft and the internet, as I did twice just while writing this sentence. In the United States, one 2013 study found that millennials check their phone 150 times a day; a different 2016 study claimed we log an average of six hours and 19 minutes of scrolling and texting and stressing out over emails per week. No one I know likes their phone. Most people I know even realize that whatever benefits the phone allows—Google Maps, Emergency Calling—are far outweighed by the distraction that accompanies it.

We know this. We know our phones suck. We even know the apps on them were engineered to be addictive. We know that the utopian promises of technology—to make work more efficient, to make connections stronger, to make photos better and more shareable, to make the news more accessible, to make communication easier—have in fact created more work, more responsibility, more opportunities to feel like a failure.

Part of the problem is that these digital technologies, from cell phones to Apple Watches, from Instagram to Slack, encourage our worst habits. They stymie our best-laid plans for self-preservation. They ransack our free time. They make it increasingly impossible to do the things that actually ground us. They turn a run in the woods into an opportunity for self-optimization. They are the neediest and most selfish entity in every interaction I have with others. They compel us to frame experiences, as we are experiencing them, with future captions, and to conceive of travel as worthwhile only when documented for public consumption. They steal joy and solitude and leave only exhaustion and regret. I hate them and resent them and find it increasingly difficult to live without them.

Digital detoxes don’t fix the problem. Moving to the woods and going full Thoreau, for most of us, is simply not an option. The only long-term fix is making the background into foreground: calling out the exact ways digital technologies have colonized our lives, aggravating and expanding our burnout in the name of efficiency.

What these technologies do best is remind us of what we’re not doing: who’s hanging out without us, who’s working more than us, what news we’re not reading. They refuse to allow our consciousness off the hook, in order to do the essential, protective, regenerative work of sublimating and repressing. Instead, they provide the opposite: a nonstop barrage of notifications and reminders and interactions. They bring life to the forefront, constantly, so that we can’t ignore it. They’re not a respite from work—or, as promised, a way to optimize your work. They’re just more work. And six months into a society-throttling pandemic, they’re more inescapable than ever.

by Anne Helen Petersen, Backchannel/Wired | Read more:

Image: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Saturday, September 26, 2020

The Last Days of a Store with the Deck Stacked Against It

“Hear what?” I muttered through my mask as I picked up my grocery bag.

"Hear that the store is closing. September 19 is the last day. We're finished."

The clerk now had my full attention. I had been shopping at the Northway Mall Carrs/Safeway for 34 years. I must have walked between my Airport Heights home and the grocery store thousands of times — in all types of weather. I had been served by several generations of clerks, served well. I probably had spent more money in this store than in any business in Anchorage.

Given there was no one in line behind me, I pushed the clerk for more. “You heard this from a manager, someone in authority, someone who knows? This is not ‘People are sayin.’”

The clerk was right, although when I asked workers why the store was closing, they had differing explanations. Some said Safeway officials didn’t want to remain in a failing mall - a dump. Some said the store had suffered intolerable losses to shoplifters. Some said Mayor Ethan Berkowitz was going to buy the mall and convert it into a homeless shelter.

Well, the Northway Mall is failing — and a dump. The owner long ago stopped investing in the facility. The last paint job must have been laid on before President Bill Clinton met Monica Lewinsky. The parking lot is often full of nasty potholes.

Shoplifting? There was a lot out in the open. Especially at the liquor store, sometimes by obviously homeless people, sometimes by well-dressed men who looked as if they were coming home from work. I watched one of these men laugh at the clerk. “What are you gonna do about it? You caught me this time — you know I’ll be back.”

The Los Angeles Times recently reported “A 2020 survey by the National Retail Federation found that theft — which the industry calls “shrink” — was at an all-time high, costing the industry $61.7 billion in fiscal year 2019, or 1.62% of retailers' profits.” Safeway has not confided in me, but I am betting 1.62% would be way under the percentage for the Northway Mall.

As for setting up the homeless in the mall, this didn’t make any sense on the face of it. For starters, the plumbing was designed for shoppers, not residents.

Change came slowly, like the leaves turning. The displays, the selections of food and other goods all looked the same for a few days. Then I saw a notice to shoppers: “The pharmacy will close Aug. 31.” A couple days later, I picked the last loaf of my favorite rye bread from a shelf, and Jewish rye never returned.

On Sept. 5, the flower stand closed. On Sept. 7, bacon was no more, while birthday cards were at 50% off. Fresh fish and seafood had disappeared. Cat food remained in abundance.

I assumed the goods would remain on the aisles where they had been located for years until everything sold. This is not how professional liquidation is done. The stockers, at night perhaps as I never saw them in action, began consolidating goods on aisles toward the center of the store. So the beans wound up with the salad dressing and olive oil. The checkers no longer knew where to send people to find items. “Nobody tells us anything,” a checker told me. “I tell customers where the cat food used to be.”

She went on to explain that Safeway management had been very good about finding jobs at other stores for the employees. Her colleagues told me the same thing. “They really were concerned about placing us,” said one.

Sign wavers began appearing at the edge of the Safeway parking lot bearing tall signs that read “Total Inventory Blowout.” I love signs like these — they are a testament to American abundance. The Russians lost the Cold War in part because they were incapable of a “Total Inventory Blowout.” Commie stores had so little. I once visited a Warsaw “supermarket” that had a single product — bottles of vinegar.

I asked one of the sign wavers about the job. “I am glad to do it — the money, but this is not a real job. I have to get a real job.” He said he was paid $10 an hour for four hours a day. I told him “You’re not getting enough” and gave him five bucks, a tip.

By Sept. 13, there was no fresh chicken and heavy discounts were in place. In the liquor store, a man and his wife, both short, chunky, of uncertain age, properly masked, bought several shopping carts full of wine and liquor. The guy put $1,300 on his credit card - and the clerk cheerfully told him, he saved $900 with the discount. I wondered, “Is the guy going to drink all that?”

On Sept. 14, I walked in at noon. Almost all the vegetable bins were empty. If you wanted broccoli and carrots, go someplace else. Safeway’s music system was piping in Tommy James' “I Think We’re Alone Now.” I usually don’t expect irony from a supermarket. (...)

A couple days later the liquor, reduced to 50% off, was gone. And there were only three or four aisles left with food. Clearly, some foods had not been sold — they had been removed by stockers. Cheese, for example, disappeared overnight.

On the morning of the last day, I walked down to the store at 7 a.m. I was the only customer. There was salsa, hummus, dried fruit, salad dressing, packaged baby food. Hey, 90% off! I bought a container or hummus and a packet of figs for 95 cents. As I checked out, I told the cashier, “I feel like crying.” She answered “Go ahead; we’ve been crying for weeks.”

Friday, September 25, 2020

Do We Really Need Daily Mail Delivery?

There has been a longstanding interest by various members of Congress and business world to privatize the USPS - allegedly to modernize and improve its service, but in real life because the USPS is a monopoly with enormous profit potential.

“These changes are happening because there’s a White House agenda to privatize and sell off the public Postal Service,” said Mark Dimondstein, president of the American Postal Workers Union. “But there’s too much approval for the organization right now. They want to separate the service from the people and then degrade it to the point where people aren’t going to like it anymore.”

This started back in the Bush administration:

"But the agency has been rapidly losing money since a 2006 law, passed with the support of the George W. Bush administration, required USPS to pre-fund employee retiree health benefits for 75 years in the future. That means the Postal Service must pay for the future health care of employees who have not even been born yet. The burden accounted for an estimated 80% to 90% of the agency’s losses before the pandemic."

Imagine any other business being told to pre-fund health benefits for the next 75 years.

Then this past year the prospect arose that disruption or slowing of the mail service might provide grounds for delegitimizing the results of mail-in ballots in the November election. Some post offices were physically removing mail-sorting machines. The justification (which may well be valid) was that the mix of mail has shifted massively away from letters to packages, and different machines are required for that purpose.

But for this post I'm going to set aside politics and just ask whether daily mail delivery is necessary in this modern era. What prompted me to do this was some interesting items I noticed in the philatelic news:

"News from vanishing postal services are familiar everywhere in these days... In Finland the Post has already dropped Tuesday, and is now planning a three-times per week delivery system. The iconic main Post office at the Helsinki city center was closed this summer, and there are not many post offices left in the city."

"Norway Post will provide every other day delivery of mail due to the decline in mail volume... Recipients will get their mail on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday one week, and Tuesday and Thursday the following week. Those who have a post office box will receive normal daily delivery each weekday... Packages will be delivered every day or every other day depending on where in Norway the household is... Newspapers will be delivered every other day, or daily if the addressee has a post office box."

Those reports were in the March 2020 issue of The Posthorn - Journal of Scandinavian Philately, a publication of the Scandinavian Collector's Club.

via:

Commerce and the World of Toys

This fascinates me. For all the wonders of industrial capitalist production it has a hard time competing with its own garbage when it comes to creating toys that hold kids’ attention. Of course the novelty of the objects that appear in our recycling bin every week give it an advantage over individual toys. Still, trash can stimulate creativity in ways that many toys simply don’t. Why can’t toy companies do a better job of engaging the imagination of children even with their massive marketing and manufacturing capabilities?

Well, because toy companies are in the business of selling toys, not the business of making them fun. Depending on your perspective this might sound either completely obvious, or far too cynical. I don’t wish to suggest the people working at these companies simply want to rob children and their parents of their money by selling them a bunch of toys that kids will forget about in a few days. But they do have to work within a capitalist system. If they can make a great toy that entertains kids for years they will, but only if it helps their bottom line. These people have jobs they want to hold onto and companies they want to keep out of the red. If a toy holds a child’s attention beyond a year, what will their parents have to buy at the holidays? The toy economy depends on the constant exhaustion of attention and pursuit of fresh toys.

This becomes very clear watching the Netflix documentary series The Toys That Made Us. Though many of the toy designers showcased in this series seem to have a genuine passion for their work, a lot of their decisions are economic ones that have to do with production costs and marketing, not stimulating creativity in children. For example, there is a team of Power Rangers because it let Bandai sell five action figures instead of just one. He-Man rode a strange oversized green tiger called Battle Cat because Mattel ran out of money for new tooling equipment to make vehicles, so they used the equipment from another toy line and just changed the color. Hasbro painted the G.I. Joe character Snake Eyes entirely black because eliminating the detail on one figure kept costs down. More broadly, the highly gendered nature of many modern toys comes not just from ingrained social norms, but from the way companies like to sell toys. They reason that by fragmenting the market into “girls toys” and “boys toys” they can make more sales than sticking with gender neutral toys. (...)

When I was a kid toys were… actually they were a lot like they are today. As much as the old man in me wants to launch into a nostalgic recollection of how much toys have changed since I was a kid, toys have changed surprisingly little since I grew up in the 80s. It’s not just that kids play with the same kinds of toys today as they did back then, action figures for instance. In many cases they play with toys that are almost identical to the ones me and my brothers played with as kids. Franchises like Transformers, Star Wars, and Power Rangers are not only still around and quite popular, their product lines have changed little in the past few decades. Just as we see the same movies endlessly rebooted, manufacturers like betting on toys that have sold well before. It feels stagnant to most of us, but it presents less of a risk than trying something new. This goes not just for action figures where I have different kinds of transforming robots marketed to different age groups, but for all the other toys that were new when I was a kid like laser tag and remote control cars.

That’s not to say a toy needs to be new to be good, fun, or imaginative. I still have a soft spot for Star Wars and though it gets repeated endlessly I find the Transformers design concept makes for engaging toys even if I wish they would stop making movies and TV shows. The robust simplicity of toy trucks means they are probably as engaging now as they were a century ago. Children have played with dolls for as long as our species has existed. Even our primate relatives play with objects in a way that resembles a child caring for a doll. A lot of the toys that occupy my kids the best are simple and time-tested. Play-Doh, art supplies, and puzzles pack a lot of bang for their buck if you want to keep your kids occupied. (...)

Although I have heaped a lot of criticism on capitalism for producing such lame toys I have to admit that it also produces some really excellent toys. I absolutely love LEGO and magnetic tiles. My kids like them too. When done right I find building toys amongst some of my favorite, not only because they entertain my kids, but because they do encourage them to create. Depending on the day, LEGO occupy them as much as their recycling bin projects.

But here I will go into old man mode and say that when I was a boy LEGO was different. You had fewer special pieces and no branded sets or movie tie-ins. (The special pieces are oddly-shaped bricks that fit very specifically into a particular place.) While a young Greg would have loved a Star Wars X-Wing LEGO set, I’m glad I only had the old space sets. This forced me to create my own star fighters which came entirely out of my head. The shift towards branded sets and the specialized pieces push kids into making the model as it exists on the box. The boxes of the old sets often showed several projects you could make with them. This let you know the pieces held more potential than what the manufacturers laid out in the single set of instructions provided. Corporate tie-ins won’t stop kids from smashing their creations to bits and building something original, and there is a broader range of LEGO available today than ever before, but it’s a clear example of purely marketing-based design choices.

Despite the continued success of the cartoon marketing model, it has an expiration date built into it. As my generation cuts the cord and moves from live tv to streaming services children don’t see advertisements for toys along with their cartoons. We don’t have cable in my home, so my kids almost never see commercials. On the occasions when we travel somewhere that has only live TV they get quite indignant that they have to sit through so many commercials. Some of their favorite Netflix shows have toys, but they only know this because Santa or some other adult came through with them. I don’t doubt that marketers have already considered this issue, but I don’t know if their new approaches can make up for the fact that the old model can’t penetrate through streaming services that don’t have ads.

In fact, the way that toys get sold has changed significantly. Since Toys R Us filed for bankruptcy we no longer have a nationwide toy store chain—thank you, private equity firms—and very few smaller independent shops. Because of hyper-capitalism run amok we now live in a world without toy stores. Places like Target have a few toy aisles, but it’s not the same. Like so much of our world today the way kids interact with toys has lost an important in-person quality. People buy toys online or grab them in a cramped aisle in a big box store that has lots of other things for sale.

The stagnation in the toy market might have something to do with the fact that much of the innovation that once went into physical toys has now gone into video games. With the power to create and interact in such detailed worlds that video games provide, small plastic figurines seem rather boring and limited. I must admit that although I grew up with video games I feel rather resistant to letting my kids play them and plan on holding this off as long as I can. I have enough trouble pulling myself away from screens and I blame this partially on spending so much time playing video games. I would like to see toys that engage kids in the physical world at least for the time being.

To that end I stopped playing video games about a decade ago. When I want to play around with electronics I make electronic music. I find this a more creative outlet that still lets me get my fix of pressing buttons and manipulating electric devices. I don’t even need to look at a screen to do it. A modest synthesizer setup will cost as much as a gaming console and a handful of games. A number of small independent companies have even seen the potential for parents sharing a passion for synthesizers with children and produced products that straddle the line between toy and instrument. Kids love to turn knobs and press buttons at least as much as adults. These synths are fun toys on their own, but also connect with more adult gear so that parents and kids can jam together. Given the independent nature of these companies some of the kid synthesizers on offer are a bit expensive. I would like to see more large manufacturers step in and make some at a lower price. Though arguably some already make synths that kids can play.

I bring this up not just because it gives an alternative to video games that I include my kids in. The world of electronic music also gives a lesson on interoperability that toy companies could learn a great deal from. The story of MIDI (musical instrument digital interface) really shows how cooperation can expand horizons and spur innovations. In the early 80s there was no standard way to synchronize electronic instruments or for them to transmit information between them. Some manufacturers had their own proprietary standards for communicating between their own synths and drum machines, but these could not be used by other manufacturers. Then engineers from different companies came together and created MIDI as a way for electronic instruments to communicate things like notes and clock data (tempo). This worked so well that the MIDI language went almost 30 years without getting an update. I can’t think of another piece of software that has gone that long without a tweak. Because of the implementation of MIDI I can own a drum machine from one manufacturer, a synth from another, a sequencer (a device that plays patterns) from a third, and they can all synchronize together. I could not do this if Roland and other companies each created their own proprietary way for instruments to communicate the way Apple and Microsoft created their own operating systems and software. Along with the increased popularity of modular synthesizers that let musicians combine different aspects of sound synthesis to create their own unique instrument, standards like MIDI and CV (control voltage) have helped expand the possibilities of what you can do with electronic instruments.

Imagine for a moment if we did something similar with building toys. Imagine if all, or at least most of them, worked together. LEGO has arguably created the best building system, so it should probably form the core of this new paradigm. But like any system it has its limits. If instead of competing with other building toys LEGO encouraged cooperation this would expand the possibilities of what you can create with LEGO. Imagine building something with LEGO, magnetic tiles, and your favorite lesser known building system. You could leverage the strengths of each and make some truly amazing things. Maybe one system lets you build bigger structures, another works better for building moving things, and a third lets you create things with more detail.

by Greg Belvedere, Current Affairs | Read more:

Image: uncredited

Thursday, September 24, 2020

Marvelous Belief

DC was Dwight Eisenhower; Marvel was John F. Kennedy. DC was Bing Crosby; Marvel was the Rolling Stones. DC was Apollo; Marvel was Dionysus.

Marvel’s guiding spirit, and its most important writer, was Stan Lee, who died in 2018 at the age of 95. Lee helped create many of the company’s iconic figures — not only Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, and the X-Men, but also the Black Panther, the Avengers, Thor, Daredevil (Daredevil!), Doctor Strange, the Silver Surfer, and Ant-Man. There were many others. Lee defined the Marvel brand. He gave readers a sense that they were in the cool kids’ club — knowing, winking, rebellious, with their own private language: “Face Forward!” “Excelsior!” “’Nuff said!”

Aside from their superpowers, Lee’s characters were vulnerable. One of them was blind; another was confined to a wheelchair. By creating superheroes who faced real-world problems (romantic and otherwise), Lee channeled the insecurities of his young readers. As he put it: “The idea I had, the underlying theme, was that just because somebody is different doesn’t make them better.” He gave that theme a political twist: “That seems to be the worst thing in human nature: We tend to dislike people who are different than we are.” DC felt like the past, and Marvel felt like the future, above all because of Marvel’s exuberance, sense of fun, and subversive energy. (...)

In terms of cultural impact, was Lee the most important writer of the last 60 years? You could make the argument. His characters have given rise to countless movies, television shows, and novels. As Liel Leibovitz puts it in his sharp and engaging new book, “Lee’s creations redefined America’s sense of itself.” Countless children, and not a few adults, have identified with Bruce Banner, alter ego of the Hulk, who warned: “Mr. McGee, don’t make me angry. You wouldn’t like me when I’m angry.” And whatever our role in life, many of us have never forgotten Lee’s line from the first Spider-Man story: “With great power there must also come — great responsibility!” If, as Shelley said, “poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” then Lee, the poet, was responsible for more than a few laws. (...)

In that respect, Lee had something in common with George Lucas, architect of the Star Wars story, who was also able to offer variations on universals. Lucas was self-conscious about his use of often-used tropes. He was greatly influenced by Joseph Campbell and his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which argued that many heroes, in many myths and religions, followed a similar arc (“the monomyth”). The arc had many ingredients, but as Campbell summarized it:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

As far as I am aware, there is no evidence that Lee read Campbell, but the lives of many of Marvel’s superheroes included important features of the monomyth, offering them enduring and cross-cultural appeal, and evidently tapping into something in the human spirit. It helped, of course, that Lee was also a terrific, inventive storyteller, with a pathbreaking insistence on seeing vulnerability, neediness, and sweetness in superheroes (Spider-Man was just a teenager who felt shy and awkward around girls).

But that wasn’t Lee’s secret sauce. It was his exuberance — contagious, joyful, defiant, and impossible to resist. When Peter Parker first meets the gorgeous Mary Jane Watson, the love of his life, her first words to him are these: “Face it, tiger … You just hit the jackpot!” For decades, one of Lee’s favorite words was “Excelsior!” In 2010, he offered a definition (on Twitter no less): “Upward and onward to greater glory!”

by Cass R. Sunstein, LARB | Read more:

History Will Judge the Complicit

In english, the word collaborator has a double meaning. A colleague can be described as a collaborator in a neutral or positive sense. But the other definition of collaborator, relevant here, is different: someone who works with the enemy, with the occupying power, with the dictatorial regime. In this negative sense, collaborator is closely related to another set of words: collusion, complicity, connivance. This negative meaning gained currency during the Second World War, when it was widely used to describe Europeans who cooperated with Nazi occupiers. At base, the ugly meaning of collaborator carries an implication of treason: betrayal of one’s nation, of one’s ideology, of one’s morality, of one’s values.

Since the Second World War, historians and political scientists have tried to explain why some people in extreme circumstances become collaborators and others do not. The late Harvard scholar Stanley Hoffmann had firsthand knowledge of the subject—as a child, he and his mother hid from the Nazis in Lamalou-les-Bains, a village in the south of France. But he was modest about his own conclusions, noting that “a careful historian would have—almost—to write a huge series of case histories; for there seem to have been almost as many collaborationisms as there were proponents or practitioners of collaboration.” Still, Hoffmann made a stab at classification, beginning with a division of collaborators into “voluntary” and “involuntary.” Many people in the latter group had no choice. Forced into a “reluctant recognition of necessity,” they could not avoid dealing with the Nazi occupiers who were running their country.

Hoffmann further sorted the more enthusiastic “voluntary” collaborators into two additional categories. In the first were those who worked with the enemy in the name of “national interest,” rationalizing collaboration as something necessary for the preservation of the French economy, or French culture—though of course many people who made these arguments had other professional or economic motives, too. In the second were the truly active ideological collaborators: people who believed that prewar republican France had been weak or corrupt and hoped that the Nazis would strengthen it, people who admired fascism, and people who admired Hitler.

Hoffmann observed that many of those who became ideological collaborators were landowners and aristocrats, “the cream of the top of the civil service, of the armed forces, of the business community,” people who perceived themselves as part of a natural ruling class that had been unfairly deprived of power under the left-wing governments of France in the 1930s. Equally motivated to collaborate were their polar opposites, the “social misfits and political deviants” who would, in the normal course of events, never have made successful careers of any kind. What brought these groups together was a common conclusion that, whatever they had thought about Germany before June 1940, their political and personal futures would now be improved by aligning themselves with the occupiers.

Like Hoffmann, Czesław Miłosz, a Nobel Prize–winning Polish poet, wrote about collaboration from personal experience. An active member of the anti-Nazi resistance during the war, he nevertheless wound up after the war as a cultural attaché at the Polish embassy in Washington, serving his country’s Communist government. Only in 1951 did he defect, denounce the regime, and dissect his experience. In a famous essay, The Captive Mind, he sketched several lightly disguised portraits of real people, all writers and intellectuals, each of whom had come up with different ways of justifying collaboration with the party. Many were careerists, but Miłosz understood that careerism could not provide a complete explanation. To be part of a mass movement was for many a chance to end their alienation, to feel close to the “masses,” to be united in a single community with workers and shopkeepers. For tormented intellectuals, collaboration also offered a kind of relief, almost a sense of peace: It meant that they were no longer constantly at war with the state, no longer in turmoil. Once the intellectual has accepted that there is no other way, Miłosz wrote, “he eats with relish, his movements take on vigor, his color returns. He sits down and writes a ‘positive’ article, marveling at the ease with which he writes it.” Miłosz is one of the few writers to acknowledge the pleasure of conformity, the lightness of heart that it grants, the way that it solves so many personal and professional dilemmas.

We all feel the urge to conform; it is the most normal of human desires. I was reminded of this recently when I visited Marianne Birthler in her light-filled apartment in Berlin. During the 1980s, Birthler was one of a very small number of active dissidents in East Germany; later, in reunified Germany, she spent more than a decade running the Stasi archive, the collection of former East German secret-police files. I asked her whether she could identify among her cohort a set of circumstances that had inclined some people to collaborate with the Stasi.

She was put off by the question. Collaboration wasn’t interesting, Birthler told me. Almost everyone was a collaborator; 99 percent of East Germans collaborated. If they weren’t working with the Stasi, then they were working with the party, or with the system more generally. Much more interesting—and far harder to explain—was the genuinely mysterious question of “why people went against the regime.” The puzzle is not why Markus Wolf remained in East Germany, in other words, but why Wolfgang Leonhard did not.

Wednesday, September 23, 2020

Tuesday, September 22, 2020

Albert Camus’s The Plague

In 1947, when he was 34, Albert Camus, the Algerian-born French writer (he would win the Nobel Prize for Literature ten years later, and die in a car crash three years after that) provided an astonishingly detailed and penetrating answer to these questions in his novel The Plague. The book chronicles the abrupt arrival and slow departure of a fictional outbreak of bubonic plague to the Algerian coastal town of Oran in the month of April, sometime in the 1940s. Once it has settled in, the epidemic lingers, roiling the lives and minds of the town’s inhabitants until the following February, when it leaves as quickly and unaccountably as it came, “slinking back to the obscure lair from which it had stealthily emerged.”

Camus shows how easy it is to mistake an epidemic for an annoyance.

Whether or not you’ve read The Plague, the book demands reading, or rereading, at this tense national and international moment, as a new disease, COVID-19, caused by a novel form of coronavirus, sweeps the globe. Since the novel coronavirus emerged late last year in the Chinese city of Wuhan (the city has been in lockdown since January), it has has gone on the march, invading more than a hundred countries, panicking populations and financial markets and putting cities, regions, and one entire country, Italy, under quarantine. This week, workplaces, schools and colleges have closed or gone online in many American towns; events have been canceled; and non-essential travel has been prohibited. The epidemic has been upgraded to pandemic. You may find yourself with more time to read than usual. Camus’s novel has fresh relevance and urgency—and lessons to give. (...)

As the story begins, rats are lurching out of Oran’s shadows, first one-by-one, then in “batches,” grotesquely expiring on landings or in the street. The first to encounter this phenomenon is a local doctor named Rieux, who summons his concierge, Michel, to deal with the nuisance, and is startled when Michel is “outraged,” rather than disgusted. Michel is convinced that young “scallywags” must have planted the vermin in his hallway as a prank. Like Michel, most of Oran’s citizens misinterpret the early “bewildering portents,” missing their broader significance. For a time, the only action they take is denouncing the local sanitation department and complaining about the authorities. “In this respect our townsfolk were like everybody else, wrapped up in themselves,” the narrator reflects. “They were humanists: they disbelieved in pestilences.” Camus shows how easy it is to mistake an epidemic for an annoyance.

But then Michel falls sick and dies. As Rieux treats him, he recognizes the telltale signs of plague, but at first persuades himself that, “The public mustn’t be alarmed, that wouldn’t do at all.” Oran’s bureaucrats agree. The Prefect (like a mayor or governor, in colonial Algeria) “personally is convinced that it’s a false alarm.” A low-level bureaucrat, Richard, insists the disease must not be identified officially as plague, but should be referred to merely as “a special type of fever.” But as the pace and number of deaths increases, Rieux rejects the euphemism, and the town’s leaders are forced to take action.

Authorities are liable to minimize the threat of an epidemic, Camus suggests, until the evidence becomes undeniable that underreaction is more dangerous than overreaction. Most people share that tendency, he writes, it’s a universal human frailty: “Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world; yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky.”

Soon the city gates are closed and quarantines are imposed, cutting off the inhabitants of Oran from each other and from the outside world. “The first thing that plague brought to our town was exile,” the narrator notes. A journalist named Rambert, stuck in Oran after the gates close, begs Rieux for a certificate of health so he can get back to his wife in Paris, but Rieux cannot help him. “There are thousands of people placed as you are in this town,” he says. Like Rambert, the citizens soon sense the pointlessness of dwelling on their personal plights, because the plague erases the “uniqueness of each man’s life” even as it heightens each person’s awareness of his vulnerability and powerlessness to plan for the future.

This catastrophe is collective: “a feeling normally as individual as the ache of separation from those one loves suddenly became a feeling in which all shared alike,” Camus writes. This ache, along with fear, becomes “the greatest affliction of the long period of exile that lay ahead.” Anyone who lately has had to cancel a business trip, a class, a party, a dinner, a vacation, or a reunion with a loved one, can feel the justice of Camus’s emphasis on the emotional fallout of a time of plague: feelings of isolation, fear, and loss of agency. It is this, “the history of what the normal historian passes over,” that his novel records, and which the novel coronavirus is now inscribing on current civic life.“A feeling normally as individual as the ache of separation from those one loves suddenly became a feeling in which all shared alike,” Camus writes.

If you read The Plague long ago, perhaps for a college class, you likely were struck most by the physical torments that Camus’s narrator dispassionately but viscerally describes. Perhaps you paid more attention to the buboes and the lime pits than to the narrator’s depiction of the “hectic exaltation” of the ordinary people trapped in the epidemic’s bubble, who fought their sense of isolation by dressing up, strolling aimlessly along Oran’s boulevards; and splashing out at restaurants, poised to flee should a fellow diner fall ill, caught up in “the frantic desire for life that thrives in the heart of every great calamity”: the comfort of community. The townspeople of Oran did not have the recourse that today’s global citizens have, in whatever town: to seek community in virtual reality. As the present pandemic settles in and lingers in this digital age, it applies a vivid new filter to Camus’s acute vision of the emotional backdrop of contagion.

Today, the exile and isolation of Plague 2.0 are acquiring their own shadings, their own characteristics, recoloring Camus’s portrait. As we walk along our streets, go to the grocery, we reflexively adopt the precautionary habits social media recommends: washing our hands; substituting rueful, grinning shrugs for handshakes; and practicing “social distancing.” We can do our work remotely to avoid infecting others or being infected; we can shun parties, concerts and restaurants, and order in from Seamless. But for how long? Camus knew the answer: we can’t know.

by Liesl Schillinger, LitHub | Read more:

Image: The dance of death: the careless and the careful. T. Rowlandson, 1816.

The Social Dilemma

They claim that the manipulation of human behavior for profit is coded into these companies with Machiavellian precision: Infinite scrolling and push notifications keep users constantly engaged; personalized recommendations use data not just to predict but also to influence our actions, turning users into easy prey for advertisers and propagandists.

As in his documentaries about climate change, “Chasing Ice” and “Chasing Coral,” Orlowski takes a reality that can seem too colossal and abstract for a layperson to grasp, let alone care about, and scales it down to a human level. In “The Social Dilemma,” he recasts one of the oldest tropes of the horror genre — Dr. Frankenstein, the scientist who went too far — for the digital age.

In briskly edited interviews, Orlowski speaks with men and (a few) women who helped build social media and now fear the effects of their creations on users’ mental health and the foundations of democracy. They deliver their cautionary testimonies with the force of a start-up pitch, employing crisp aphorisms and pithy analogies.

“Never before in history have 50 designers made decisions that would have an impact on two billion people,” says Tristan Harris, a former design ethicist at Google. Anna Lembke, an addiction expert at Stanford University, explains that these companies exploit the brain’s evolutionary need for interpersonal connection. And Roger McNamee, an early investor in Facebook, delivers a chilling allegation: Russia didn’t hack Facebook; it simply used the platform. (...)

Despite their vehement criticisms, the interviewees in “The Social Dilemma” are not all doomsayers; many suggest that with the right changes, we can salvage the good of social media without the bad. But the grab bag of personal and political solutions they present in the film confuses two distinct targets of critique: the technology that causes destructive behaviors and the culture of unchecked capitalism that produces it.

Nevertheless, “The Social Dilemma” is remarkably effective in sounding the alarm about the incursion of data mining and manipulative technology into our social lives and beyond. Orlowski’s film is itself not spared by the phenomenon it scrutinizes. The movie is streaming on Netflix, where it’ll become another node in the service’s data-based algorithm.

by Devika Girish, NY Times | Read more:

Image: Netflix

America’s Plastic Hour Is Upon Us

Are we living in a plastic hour? It feels that way.

Beneath the dreary furor of the partisan wars, most Americans agree on fundamental issues facing the country. Large majorities say that government should ensure some form of universal health care, that it should do more to mitigate global warming, that the rich should pay higher taxes, that racial inequality is a significant problem, that workers should have the right to join unions, that immigrants are a good thing for American life, that the federal government is plagued by corruption. These majorities have remained strong for years. The readiness, the demand for action, is new.

What explains it? Nearly four years of a corrupt, bigoted, and inept president who betrayed his promise to champion ordinary Americans. The arrival of an influential new generation, the Millennials, who grew up with failed wars, weakened institutions, and blighted economic prospects, making them both more cynical and more utopian than their parents. Collective ills that go untreated year after year, so bone-deep and chronic that we assume they’re permanent—from income inequality, feckless government, and police abuse to a shredded social fabric and a poisonous public discourse that verges on national cognitive decline. Then, this year, a series of crises that seemed to come out of nowhere, like a flurry of sucker punches, but that arose straight from those ills and exposed the failures of American society to the world.

The year 2020 began with an impeachment trial that led to acquittal despite the president’s obvious guilt. Then came the pandemic, chaotic hospital wards, ghost cities, lies and conspiracy theories from the White House, mass death, mass unemployment, police killings, nationwide protests, more sickness, more death, more economic despair, the disruption of normal life without end. Still ahead lies an election on whose outcome everything depends.

The year 1968—with which, for concentrated drama, 2020 is sometimes compared—marked the end of an era of reform and the start of a conservative reaction that resonated for decades. In 1968 the core phenomenon was the collapse of order. In 2020 it is the absence of solidarity. Even with majorities agreeing on central issues, there’s little sense of being in this together. The United States is world-famously individualistic, and the past half century has seen the expansion of freedom in every direction—personal, social, financial, technological. But the pandemic demonstrates, almost scientifically, the limits of individualism. Everyone is vulnerable. Everyone’s health depends on the health of others. No one is safe unless everyone takes responsibility for the welfare of others. No person, community, or state can withstand the plague without a competent and active national government.

The story of the coronavirus in this country is a sequence of moments when this lesson broke down—when politicians spurned experts, governors reopened their states too soon, crowds liberated themselves in rallies and bars. The graph that shows the course of new infections in the United States—gradually falling in late spring, then rising sharply in summer—is an illustration of both ineffectual leadership and a failed ideology. Shame is not an emotion that Americans readily indulge, but the spectacle of the national coronavirus case rate surging ahead of India’s and Brazil’s while it declined in most rich countries has produced a wave of self-disgust here, and pity and contempt abroad.

“We’re at this moment where, because of COVID‑19, it is there for anybody who has eyes to see that the systems we are committed to are inadequate or have collapsed,” Maurice Mitchell, the director of the left-wing Working Families Party, told me. “So now almost all 300-plus million of us are in this moment of despair, asking ourselves questions that are usually the province of the academy, philosophical questions: Who am I in relation to my society? What is the role of government? What does an economy do? ”

Monday, September 21, 2020

‘This is the Worst Thing Ever’

“I’ve got two tickets for sale!” he shouts, at no one in particular.

Then, with his flowing brown hair flapping in the breeze, he lets out a booming laugh.

Inside Gantry Public House across the street, Farshid Varamini gets the joke.

But he might not find it funny.

After all, Varamini opened Gantry Public House in late February — just weeks before COVID-19 unsuspectingly squashed the Mariners’ and Sounders’ seasons and sapped his revenue stream. He also operates several “The People’s Burger” food trucks and two Pioneer Grill hot dog carts outside the stadium, and says that business is down 80-85% year-over-year.

Still, he perseveres — even during a home opener without fans at CenturyLink Field. On Sunday night, Gantry Public House, The People’s Burger and Pioneer Grill were all open for business.

But it’s not business as usual.

“It’s very different,” Varamini says, sitting at a table in his modestly filled restaurant at 3:58 p.m. ahead of a scheduled 5:20 p.m. Seahawks kickoff. “This will be year 23 that I’m down here, and we’ve done every Mariner game, every football game. I’ve never been closed. So to see this … usually I would get down here at 4 in the morning. Today I was able to sleep in and get here around 9.”

Varamini was born in Iran and came to Seattle when he was 7. He operated his first Pioneer Grill hot dog cart when he was 18. When he says he built this place, he means it; besides the plumbing and electrical, Varamini constructed much of the interior of Gantry Public House himself.

Which is all to say, this Seahawks home opener should have been a celebration — a culmination of two-plus decades of diligent work. It should have been a boon to his brand-new business.

Instead, it’s anything but.

“The first couple weeks (after COVID-19 hit) were eerie — coming down here and not seeing anything,” he says. “It’s gotten a little more normal. I’m still coming to work. We still need to make sure machines are running and things like that. Normally you couldn’t even see the sidewalk or the roads out here, because there’s so many people, not to mention all the noise.

“I’m not going to try to get used to it, is what I’m trying to say.”

Further down the block, Hector Ramos says the same. He’s standing alone in the parking lot he owns on Occidental Avenue, wearing a blue Bobby Wagner jersey and a matching Seahawks mask. It’s 4:08 p.m., barely an hour before kickoff, and the parking lot is empty.

Ramos doesn’t mince his words.

“This is the worst thing ever,” he says. “I’ve been doing this for so many years. I came today to see what was going on, whether the police would come and try to close the streets, or to watch for people or anything. I found out there’s no business. There isn’t anything.”

There is only Ramos, standing in a parking lot made abruptly obsolete. He says, in a normal season, the 20-some spots would always sell out — fetching between $50 and $100 each, depending on the size of the spot or how long they plan to stay. He actually calls his customers “friends,” because so many have reserved the same spots for countless Seahawks Sundays. They tailgate together and talk to each other; some never enter the stadium and watch from here instead.

“I don’t need to even announce it anymore,” says Ramos, who moved to the United States from Mexico City 22 years ago and has owned the parking lot for 20. “My customers are regular customers. I’m here every year and I have customers who have been coming here for 10 years. So I don’t have to advertise my business. They just come. They just come, every year.”

Every year but one.