[ed. More than anyone probably wants to know (or can understand) about prediction markets.]

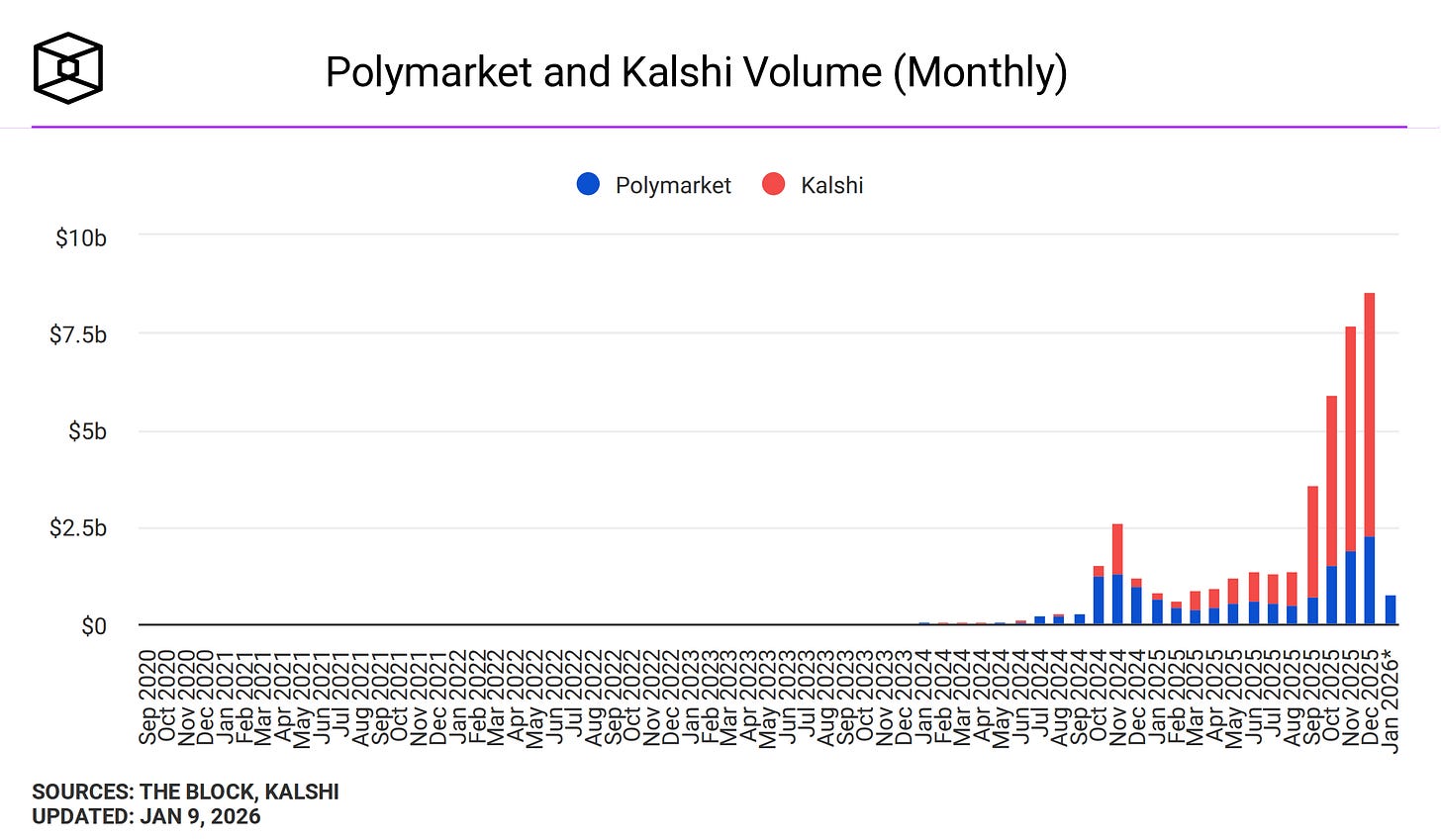

Since we last spoke, prediction markets have gone to the moon, rising from millions to billions in monthly volume.

For a few weeks in October, Polymarket founder Shayne Coplan was the world’s youngest self-made billionaire (now it’s some AI people). Kalshi is so accurate that it’s getting called a national security threat.

The catch is, of course, that it’s mostly degenerate gambling, especially sports betting. Kalshi is 81% sports by monthly volume. Polymarket does better - only 37% - but some of the remainder is things like this $686,000 market on how often Elon Musk will tweet this week - currently dominated by the “140 - 164 times” category.

(ironically, this seems to be a regulatory difference - US regulators don’t mind sports betting, but look unfavorably on potentially “insensitive” markets like bets about wars. Polymarket has historically been offshore, and so able to concentrate on geopolitics; Kalshi has been in the US, and so stuck mostly to sports. But Polymarket is in the process of moving onshore; I don’t know if this will affect their ability to offer geopolitical markets)

Degenerate gambling is bad. Insofar as prediction markets have acted as a Trojan Horse to enable it, this is bad. Insofar as my advocacy helped make this possible, I am bad. I can only plead that it didn’t really seem plausible, back in 2021, that a presidential administration would keep all normal restrictions on sports gambling but also let prediction markets do it as much as they wanted. If only there had been some kind of decentralized forecasting tool that could have given me a canonical probability on this outcome!

Still, it might seem that, whatever the degenerate gamblers are doing, we at least have some interesting data. There are now strong, minimally-regulated, high-volume prediction markets on important global events. In this column, I previously claimed this would revolutionize society. Has it?

I don’t feel revolutionized. Why not?

The problem isn’t that the prediction markets are bad. There’s been a lot of noise about insider trading and disputed resolutions. But insider trading should only increase accuracy - it’s bad for traders, but good for information-seekers - and my impression is that the disputed resolutions were handled as well as possible. When I say I don’t feel revolutionized, it’s not because I don’t believe it when it says there’s a 20% chance Khameini will be out before the end of the month. The several thousand people who have invested $6 million in that question have probably converged upon the most accurate probability possible with existing knowledge, just the way prediction markets should.

I actually like this. Everyone is talking about the protests in Iran, and it’s hard to gauge their importance, and knowing that there’s a 20% chance Khameini is removed by February really does help to place them in context. The missing link seems to be between “it’s now possible to place global events in probabilistic context → society revolutionized”.

Here are some possibilities:

Maybe people just haven’t caught on yet? Most news sources still don’t cite prediction markets, even when many people would care about their outcome. For example, the Khameini market hasn’t gotten mentioned in articles about the Iran protests, even though “will these protests succeed in toppling the regime?” is the obvious first question any reader would ask.

Maybe the problem is that probabilities don’t matter? Maybe there’s some State Department official who would change plans slightly over a 20% vs. 40% chance of Khameini departure, or an Iranian official for whom that would mean the difference between loyalty and defection, and these people are benefiting slightly, but not enough that society feels revolutionized.

Maybe society has been low-key revolutionized and we haven’t noticed? Very optimistically, maybe there aren’t as many “obviously the protests will work, only a defeatist doomer traitor would say they have any chance of failing!” “no, obviously the protests will fail, you’re a neoliberal shill if you think they could work” takes as there used to be. Maybe everyone has converged to a unified assessment of probabilistic knowledge, and we’re all better off as a result.

Maybe Polymarket and Kalshi don’t have the right questions. Ask yourself: what are the big future-prediction questions that important disagreements pivot around? When I try this exercise, I get things like:

- Will the AI bubble pop? Will scaling get us all the way to AGI? Will AI be misaligned?

- Will Trump turn America into a dictatorship? Make it great again? Somewhere in between?

- Will YIMBY policies lower rents? How much?

- Will selling US chips to China help them win the AI race?

- Will kidnapping Venezuela’s president weaken international law in some meaningful way that will cause trouble in the future?

- If America nation-builds Venezuela, for whatever definition of nation-build, will that work well, or backfire?

Annals of The Rulescucks

The new era of prediction markets has provided charming additions to the language, including “rulescuck” - someone who loses an otherwise-prescient bet based on technicalities of the resolution criteria.

Resolution criteria are the small print explaining what counts as the prediction market topic “happening'“. For example, in the Khameini example above, Khameini qualifies as being “out of power” if:

…he resigns, is detained, or otherwise loses his position or is prevented from fulfilling his duties as Supreme Leader of Iran within this market's timeframe. The primary resolution source for this market will be a consensus of credible reporting.You can imagine ways this definition departs from an exact common-sensical concept of “out of power” - for example, if Khameini gets stuck in an elevator for half an hour and misses a key meeting, does this count as him being “prevented from fulfilling his duties”? With thousands of markets getting resolved per month, chances are high that at least one will hinge upon one of these edge cases.

Kalshi resolves markets by having a staff member with good judgment decide whether or not the situation satisfies the resolution criteria.

Polymarket resolves markets by . . . oh man, how long do you have? There’s a cryptocurrency called UMA. UMA owners can stake it to vote on Polymarket resolutions in an associated contract called the UMA Oracle. Voters on the losing side get their cryptocurrency confiscated and given to the winners. This creates a Keynesian beauty contest, ie a situation where everyone tries to vote for the winning side. The most natural Schelling point is the side which is actually correct. If someone tries to attack the oracle by buying lots of UMA and voting for the wrong side, this incentivizes bystanders to come in and defend the oracle by voting for the right side, since (conditional on there being common knowledge that everyone will do this) that means they get free money at the attackers’ expense. But also, the UMA currency goes up in value if people trust the oracle and plan to use it more often, and it goes down if people think the oracle is useless and may soon get replaced by other systems. So regardless of their other incentives, everyone who owns the currency has an incentive to vote for the true answer so that people keep trusting the oracle. This system works most of the time, but tends towards so-called “oracle drama” where seemingly prosaic resolutions might lie at the end of a thrilling story of attacks, counterattacks, and escalations.

Here are some of the most interesting alleged rulescuckings of 2026:

Mr Ozi: Will Zelensky wear a suit? Ivan Cryptoslav calls this “the most infamous example in Polymarket history”. Ukraine’s president dresses mostly in military fatigues, vowing never to wear a suit until the war is over. As his sartorial notoriety spread, Polymarket traders bet over $100 million on the question of whether he would crack in any given month. At the Pope’s funeral, Zelensky showed up in a respectful-looking jacket which might or might not count. Most media organizations refused to describe it as a “suit”, so the decentralized oracle ruled against. But over the next few months, Zelensky continued to straddle the border of suithood, and the media eventually started using the word “suit” in their articles. This presented a quandary for the oracle, which was supposed to respect both the precedent of its past rulings, and the consensus of media organizations. Voters switched sides several times until finally settling on NO; true suit believers were unsatisfied with this decision. For what it’s worth, the Twitter menswear guy told Wired that “It meets the technical definition, [but] I would also recognize that most people would not think of that as a suit.”

[more examples...]

With one exception, these aren’t outright oracle failures. They’re honest cases of ambiguous rules.

Most of the links end with pleas for Polymarket to get better at clarifying rules. My perspective is that the few times I’ve talked to Polymarket people, I’ve begged them to implement various cool features, and they’ve always said “Nope, sorry, too busy figuring out ways to make rules clearer”. Prediction market people obsess over maximally finicky resolution criteria, but somehow it’s never enough - you just can’t specify every possible state of the world beforehand.

The most interesting proposal I’ve seen in this space is to make LLMs do it; you can train them on good rulesets, and they’re tolerant enough of tedium to print out pages and pages of every possible edge case without going crazy. It’ll be fun the first time one of them hallucinates, though.

With one exception, these aren’t outright oracle failures. They’re honest cases of ambiguous rules.

Most of the links end with pleas for Polymarket to get better at clarifying rules. My perspective is that the few times I’ve talked to Polymarket people, I’ve begged them to implement various cool features, and they’ve always said “Nope, sorry, too busy figuring out ways to make rules clearer”. Prediction market people obsess over maximally finicky resolution criteria, but somehow it’s never enough - you just can’t specify every possible state of the world beforehand.

The most interesting proposal I’ve seen in this space is to make LLMs do it; you can train them on good rulesets, and they’re tolerant enough of tedium to print out pages and pages of every possible edge case without going crazy. It’ll be fun the first time one of them hallucinates, though.

…And Miscellaneous N’er-Do-Wells

I include this section under protest.

The media likes engaging with prediction markets through dramatic stories about insider trading and market manipulation. This is as useful as engaging with Waymo through stories about cats being run over. It doesn’t matter whether you can find one lurid example of something going wrong. What matters is the base rates, the consequences, and the alternatives. Polymarket resolves about a thousand markets a month, and Kalshi closer to five thousand. It’s no surprise that a few go wrong; it’s even less surprise that there are false accusations of a few going wrong.

Still, I would be remiss to not mention this at all, so here are some of the more interesting stories:

by Scott Alexander, Astral Codex Ten | Read more:

Images: uncredited

Images: uncredited